Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this article is to study attitudes about sperm donation and willingness to donate sperm in students who have never shown an interest in sperm donation.

Methods

The method used in this study is an electronic survey of 1012 male students.

Results

Only one third of the respondents (34.3%) would consider donating sperm. Overall, 85.7% indicated a positive attitude towards sperm donation while 14.3% indicated a neutral or negative attitude. The highest scored barriers to donating were the lack of practical information and the fear that the partner would not agree. Almost 40% of the respondents feared that the donation might have a negative impact on their current or future relationship. The majority (83.6%) of those who considered donating thought donors should receive a financial compensation. Money was also one of the main motivators.

Conclusions

About 85% of the students thought positively about sperm donation but several factors such as perceived negative views by the social environment, especially the partner, may deter students from donating. This study indicates that the effect of strong incentives, for instance in monetary terms, on a donor pool consisting of students could be limited and that relational factors and donor’s perceptions of the views of the wider social network should be taken into account when recruiting donors.

Keywords: Attitude, Donor conception, Intention, Sperm donation, Students

Introduction

Many countries in Europe, such as Belgium, France, Italy, Ireland, UK, Germany and the Netherlands, struggle to recruit a sufficient number of sperm donors. The difficulty of attracting men for this service is undoubtedly linked to the controversial nature of sperm donation. Religious, psychological and moral reasons partially determine how men look at sperm donation [1]. However, the empirical evidence to support this statement is insubstantial. A literature search shows that there are very few studies on the attitude of the general population vis-à-vis sperm donation. In the systematic overview by Van den Broeck [2], only one study focused exclusively on non-donors and two studies included both non-donors and actual or potential donors. After a thorough search, some additional studies on attitudes of non-donors were found: Lampiao, 2013 [3] in Malawi, Hedrih and Hedrih, 2012 [4] in Serbia and Onah et al., 2008 [5] in Nigeria. These studies came from countries in which few studies are performed about assisted reproduction.

Knowledge of and insight into men’s thinking about sperm donation might help to achieve two goals: first, to find out whether measures are needed to increase the acceptance of sperm donation as such and second, to find out whether adaptations are needed in the recruitment campaigns. For the second goal, one should distinguish between those who would consider donating and those who would under no circumstances donate. The beliefs (for instance about identifiability and payment of donors) of people who would not consider donating do not matter for donor recruitment since these people will never come forward as donors. Therefore, gaining knowledge about the opinion of the general population in light of designing better campaigns is not sufficient.

Information on how non-donors think about sperm donation cannot be obtained by questioning the candidate donors or actual donors. Among the candidate donors (men who have taken steps such as presenting themselves at a sperm bank or clinic), one would expect a bias toward existing practice. For example, the donor pool recruited in an anonymous system can be expected to be largely in favour of anonymity. Those who are strongly against anonymity will simply exclude themselves. The same is true for payment and other rules of the practice. One can ask counterfactual hypothetical questions such as ‘would you also donate if …’. In that case, one will find out what would happen to the existing donor pool if things change but not what the effect of a rule would be on recruitment in the general population. In a recent study among sperm donors in Belgium, donors were asked whether they would continue donating if donor anonymity would be abolished [6]. It turned out that 71% would stop donating. Nevertheless, questioning candidate donors is more useful than actual donors since the selection criteria to be accepted as a donor have very little to do with opinions or intentions but with medical/genetic standards.

The aim of this study is to describe students’ attitudes about sperm donation and their willingness to donate sperm using an anonymous questionnaire among a large sample of students that had never shown an interest in sperm donation. By questioning men who had not shown an interest in donating before, we excluded self-selection in the sample. Besides the practical advantages in reaching this group, students are of the right age for sperm donation. Moreover, since the Belgian law does not allow sperm banks or fertility clinics to launch campaigns to directly recruit donors, most clinics recruit among students at the local campus or hospital site. Participants were informed about the legal situation in Belgium: men between 18 and 45 can donate anonymously but known donation is possible when both donor and recipient agree. The anonymous donors do not receive information on the recipients but they are aware that their sperm can be used for heterosexual and lesbian couples and for single women. A donor can be used for a maximum of six women. Donating gametes is for free (for altruistic reasons) but reimbursement of expenses is allowed [7].

Materials and methods

The research population consisted of approximately 52,000 Dutch-speaking students studying at two colleges in Ghent (HoGent and Sint-Lucas Gent) and all 11 faculties of Ghent University, Belgium. Each college and faculty made use of its own procedure to approach students to invite them to participate in the study, either through an announcement on their main electronic learning platform or via e-mail. Ghent University sent a general newsletter to its 41,000 students with a link to the survey and announced the study on a webpage dedicated to actual research projects of the University. Later on, the faculties of Ghent University put an announcement on their electronic learning platform, send an e-mail or put it on their Facebook webpage. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University Hospital.

Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the questionnaire took about 10 min to complete. As an incentive, respondents could participate in a lottery to win an Apple Ipad mini.

Between December 2014 and February 2015, 1012 male respondents completed the questionnaire.

The questionnaire started with four introductory questions about socio-demographic features of the students (gender, age, relationship status and sexual orientation). These questions were either needed to exclude respondents in the analysis (e.g. women) or to offer the students tailored questions (e.g. questions about partners were asked only to students who were in a partner relationship). The first part of the questionnaire started with a general question about what they thought about sperm donation, to be scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7). Students were asked whether they would be willing to use donated sperm in case they would face fertility problems, whether they ever donated sperm and, if not, whether or not they ever considered donating. These latter questions were used to filter out all students who did not belong to our targeted sample of students who never showed an interest in donating sperm.

The second part of the questionnaire was designed to measure the students’ attitudes towards (specific rules or policies about) sperm donation. Therefore, 13 5-point Likert-type statements (strongly agree, agree, neutral point, disagree and strongly disagree) were used (see Table 2). Furthermore, questions were asked about what conditions they would attach to sperm donation, what would motivate them to donate, and what they saw as barriers to sperm donation (all to be scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale). The students were also asked if they thought sperm donors should receive financial compensation, and (for those who agreed) from what amounts they would consider donating. Other questions were about potential social support and views of significant others towards sperm donation.

Table 2.

Opinions about sperm donation in students who considered donating versus those who did not consider donating and in students with or without a positive attitude towards sperm donation

| Considered donatinga (N = 319) | Did not consider donatinga (N = 610) | A positive attitudec (N = 798) | A neutral or negative attitudec (N = 135) | Totale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | |

| Sperm donation in general | |||||

| Sperm donation is a good way to help childless couples | 276 (90.8)*** | 464 (80.8) | 679 (90.3)*** | 61 (48.4) | 740 (84.3) |

| I think there is a shortage of sperm donors in Belgium | 153 (50.5)*** | 211 (37.1) | 328 (43.9)*** | 36 (28.8) | 364 (41.7) |

| Couples who cannot have children should stay childless | 7 (2.3) | 23 (4.0) | 9 (1.2)*** | 21 (16.7) | 30 (3.4) |

| Genetic parenthood | |||||

| People always love genetically related children more than children who are not genetically related | 38 (12.5)* | 101 (17.8) | 101 (13.5)*** | 38 (30.4) | 139 (15.9) |

| True parenthood can only exist when there is a genetic link between parents and children | 33 (10.9)* | 88 (15.3) | 89 (11.8)*** | 32 (25.4) | 121 (13.8) |

| Consequences of sperm donation | |||||

| A sperm donor can be asked to pay maintenance for the children conceived with his sperm | 3 (1.0) | 12 (2.1) | 8 (1.1)** | 7 (5.6) | 15 (1.7) |

| Children conceived with donor sperm have a higher risk of psychological problems | 17 (5.6)* | 52 (9.1) | 39 (5.2)*** | 30 (23.8) | 69 (7.9) |

| Opinions about being a sperm donor or using donated sperm | |||||

| Donating sperm goes against my principles | 13 (4.3)*** | 86 (15.1) | 37 (5.0)*** | 62 (49.6) | 99 (11.4) |

| I am afraid I will regret it later if I donate sperm | 80 (26.4)* | 196 (34.4) | 205 (27.4)*** | 71 (56.8) | 276 (31.7) |

| I would consider using donor sperm if me or my (future) partner would have fertility problems | 91 (31.1)* | 134 (24.0) | 210 (29.0)*** | 15 (11.8) | 225 (26.4) |

| If I would donate sperm, I would want to meet the children conceived with my sperm (once) | 77 (25.3) | 130 (22.6) | 167 (22.2)* | 40 (31.7) | 207 (23.6) |

| I am afraid I will regret it later if I do not donate sperm | 25 (8.2)*** | 8 (1.4) | 30 (4.0) | 3 (2.4) | 33 (3.8) |

| Financial compensation | |||||

| Most men donate for the money | 151 (49.8)* | 243 (42.7) | 326 (43.6)* | 68 (54.4) | 394 (45.2) |

| Do you think sperm donors should receive a financial compensation?d | 246 (83.4)*** | 357 (65.0) | 191 (26.3)*** | 50 (42.7) | 603 (71.4) |

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. p value based on Chi2 test to compare the proportion of respondents (totally) agreeing between ‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’ (indicated in the column ‘considered donating’); and between ‘A positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’ (indicated in the column ‘A positive attitude’)

a4 missing cases for ‘considered donating/did not consider donating’

bNumber and percentage of respondents answering ‘rather agree’ or ‘totally agree’ within each category (‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’; and ‘a positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’)

cAttitude scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7); positive: all students who scored ≤ 3; not positive: all students who scored ≥ 4

dThis question was asked separately, to be scored with a yes or no. Number and percentage of those answering ‘yes’ is presented

eNumber of missing cases per statement varied from 55 to 61

The third part of the questionnaire measured the remaining socio-demographics including their domain of education (what subjects they studied), whether or not they had children and their religion. The religion variable distinguishes between two groups: students who have a denominative religion (Christian, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Islamic) and those who are not religious or who do not have a specific religion or denomination (religious but no specific religion, secular and humanist). At the end, students were also asked whether they knew sperm donors, people with fertility problems or people conceived via sperm donation and whether they ever looked for information about sperm donation or talked about sperm donation with friends, family or their partner.

The Statistical Package of the Social Sciences (SPSS version 21) was used for the analysis. Individual χ 2 tests were undertaken to explore the significance of the association between variables. In case the assumption of χ 2, which states that no > 20% of cells can have a cell frequency count of < 5 and that no cells may have a cell frequency count of zero, was not met, Cramers’ V was alternatively used. χ 2 and Cramer’s V were used to analyse the significance of the association between having considered donating and/or not having considered donating sperm (or having a positive versus a neutral or negative attitude towards sperm donation) and socio-demographic variables, attitudes towards sperm donation, ideal conditions, motivations and barriers for donating sperm, perceived social support (expressed as approval/disapproval of significant others in case the respondent would donate sperm) and importance of social support for their intention to donate sperm. To compare mean age, the independent sample t test was used.

Results

Of the 1012 surveys received, 77 men were excluded after data-cleaning: 60 men because they had not answered several important questions and 17 men because they indicated that they donated sperm before. In total, 935 men were included in the analysis. The majority of the respondents were heterosexual (88.1%), almost half of them (42.8%) had a relationship and only a few respondents (1.1%) had children of their own (see Table 1). The average age was a little over 22 years and most men were not religious (67.2%). Religious students less often reported to have considered sperm donation, compared to students who were not religious. With respect to the domain of students’ education, no statistical significant differences were found when students of particular domains were compared with all others (data not shown in the table).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Considered donating (N = 319)a | Did not consider donating (N = 610)a | A positive attitudeb (N = 798) | A neutral or negative attitudeb (N = 135) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sexual orientationc | |||||

| Heterosexual | 274 (86.4) | 542 (89.0) | 693 (87.1)* | 126 (94.0) | 816 (88.1) |

| Homosexual or bisexual | 43 (13.6) | 67 (11.0) | 103 (12.9) | 8 (6.0) | 110 (11.9) |

| Relationshipc | |||||

| Single | 177 (55.5) | 354 (58.0) | 448 (56.1) | 87 (64.4) | 531 (57.2) |

| In a relationship | 143 (44.5) | 256 (42.0) | 350 (43.9) | 48 (35.6) | 398 (42.8) |

| Religiond | |||||

| Religious | 68 (25.4)* | 183 (36.8) | 205 (31.0) | 46 (44.7) | 251 (32.8) |

| Not religious | 200 (74.6) | 314 (63.2) | 457 (69.0) | 57 (55.3) | 514 (67.2) |

| Childrenc | |||||

| Yes | 2 (0.7)* | 7 (1.4) | 7 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 9 (1.1) |

| No | 274 (98.6) | 503 (97.7) | 673 (98.2) | 104 (96.3) | 777 (98.0) |

| Othere | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) | 5 (0.7) | 2 (1.9) | 7 (0.9) |

| Agef | 22.47 ± 2.8 (SE 0.155) | 22.01 ± 2.7 (SE 0.111) | 22.13 ± 2.7 (SE 0.097) | 22.33 ± 2.8 (SE 0.245) | 22.16 |

*p ≤ 0.05. No p values were ≤ 0.01. p value based on Chi2 test to compare the proportion of respondents (totally) agreeing between ‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’ (indicated in the column ‘considered donating’); and between ‘A positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’ (indicated in the column ‘A positive attitude’)

a4 missing cases for ‘considered donating/did not consider donating’

bAttitude scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7); positive: all students who scored ≤ 3; not positive: all students who scored ≥ 4

cNumber of missing cases for demographic characteristics: 3 for sexual orientation, 168 for religion, and 140 for children (questions situated at the end of the questionnaire)

dThe religion variable distinguishes between two groups: students who have a denominative religion (Christian, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Islamic) and those who are not religious or who do not have a specific religion or denomination (religious but no specific religion, secular and humanist)

ei.e. expecting a child, partner has child(ren), etc.

fMean age per category

Two thirds of the respondents (65.7%) would not consider donating while one third (34.3%) would. The general attitude of the respondents towards sperm donation as measured on a 7-point Likert scale was highly positive: 85.7% indicated a positive attitude while 14.3% indicated a neutral or negative attitude. In what follows, we dichotomized this variable: those with a ‘positive attitude’ (score 1–3) and those with a ‘neutral or negative attitude’ (score ≥ 4). Men with a positive attitude were more likely to be gay. No significant differences were found for the other characteristics between men with a positive versus those with a neutral or negative attitude towards sperm donation.

Opinions about sperm donation

An overwhelming majority saw sperm donation as a good way to help childless couples (Table 2). In general, students did not think that a genetic link between child and parent(s) was important: 3.4% agreed with the statement that couples who cannot have children should remain childless, 13.8% with the statement that true parenthood can only exist when there is a genetic link between parents and children and 15.9% with the statement that people always love genetically related children more than children who are not genetically related.

One quarter (26.4%) of all students would consider using donor sperm if they would face fertility problems. Less than 1 in 2 respondents (41.7%) thought there was a shortage of sperm donors in Belgium. Those who considered donating were significantly more often aware of this shortage (50.5%) than those who did not consider donating (37.1%). Students were well aware that donors cannot be asked to pay maintenance for the children conceived with their sperm: only 1.7% thought that a sperm donor can be asked to pay maintenance for the children conceived with his sperm (Table 2).

Overall, students with a positive attitude differed significantly in their opinions about all statements from those with a neutral or negative attitude. More than twice the number of students with a negative attitude towards sperm donation (compared to their counterparts with a more positive outlook on sperm donation) believed that people always love genetically related children more and that a genetic link is a precondition for true parenthood. More than four times as many of them thought that donor conceived children had a higher risk of psychological problems.

Conditions for donation

In general, the conditions of the donation did not seem to play a major role in the men’s decision to consider sperm donation (Table 3). The items can be bundled in three groups: information about the child or the recipients given to the donor, information about the donor given to the child and the relationship between the donor and the recipients. Regarding the information about the child or the recipients, 38% of the respondents would want to know how many children were born, 35% would like to receive information about the wellbeing of the child, 29% general information such as physical characteristics and interests, 27% about the family and 15% would like to know the name of the children. Those who considered donating systematically wanted more information about the child (or the recipients) than those who did not consider donating but the differences per item were not statistically significant. In general, although 37.9% was interested in knowing the number of offspring conceived with their sperm, relatively few men wanted information about the individual offspring. More interest is pronounced in the wellbeing of the child than in names and characteristics of the conceived children or their prospective parents. The only significant difference was found for a condition relating to the information flow from the donor to the child: those who considered donating (61.7%) more often declined any provision of information about themselves to the recipients and offspring compared to those who did not consider donating (52.6%). About one in four would consider donating if the children would be able to find out their identity and about one in three would be willing to share non-identifying information about themselves. The condition of knowing the recipients or directing their sperm only to certain groups of recipients played a role in only a small number of respondents.

Table 3.

Conditions for donating sperm in students who considered donating versus those who did not consider donating and in students with or without a positive attitude towards sperm donation

| I would consider donating sperm…a | Considered donating (N = 319)b | Did not consider donating (N = 610)b | A positive attituded (N = 798) | A neutral or negative attituded (N = 135) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)c | n (%)c | n (%)c | n (%)c | n (%) | |

| Information about the child or the recipients given to the donor | |||||

| if I can know how many children were conceived with my sperm | 121 (41.0) | 199 (36.2) | 275 (37.8) | 45 (38.5) | 320 (37.9) |

| if I can get the names of the children conceived with my sperm | 49 (16.6) | 77 (14.1) | 109 (15.0) | 17 (14.5) | 126 (14.9) |

| if I get general information about the children conceived with my sperm (e.g. about their physical characteristics and interests) | 74 (25.1) | 118 (21.5) | 163 (22.4) | 29 (24.8) | 191 (22.7) |

| if I can get to know something about the family in which the children conceived with my sperm will grow up | 85 (28.8) | 146 (26.6) | 198 (27.2) | 33 (28.2) | 231 (27.4) |

| if I get information about the wellbeing of the children conceived with my sperm | 110 (37.3) | 189 (34.4) | 263 (36.2) | 36 (30.8) | 299 (35.4) |

| Information about the donor given to the child | |||||

| if the prospective parents and the children conceived with my sperm will not receive information about me | 182 (61.7)* | 289 (52.6) | 417 (57.4)* | 54 (46.2) | 471 (55.8) |

| when the children conceived with my sperm would be able to know my name when they want to (later) | 75 (25.4) | 144 (26.2) | 192 (26.4) | 27 (23.1) | 219 (25.9) |

| if the children conceived with my sperm would receive general information about me (e.g. about my physical characteristics and interests) | 99 (33.6) | 184 (33.5) | 36 (30.8) | 247 (34.0) | 283 (33.5) |

| The relationship between the donor and the recipients | |||||

| if the prospective parents are people I know well | 28 (9.5) | 73 (13.3) | 16 (13.7) | 85 (11.7) | 101 (12.0) |

| if I can decide to whom my sperm will go (a heterosexual couple, a lesbian couple or a single woman) | 53 (18.0) | 101 (18.4) | 33 (28.2)** | 121 (16.6) | 154 (18.2) |

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01. No p values were ≤ 0.001. p value based on Chi2 test to compare the proportion of respondents (totally) agreeing between ‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’ (indicated in the column ‘considered donating’); and between ‘A positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’ (indicated in the column ‘A positive attitude’)

aNumber of missing cases per condition varied from 89 to 90

b4 missing cases

cRespondents answering ‘rather agree’ or ‘totally agree’ within each category (‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’; and ‘a positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’)

dAttitude scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7); positive: all students who scored ≤ 3; not positive: all students who scored ≥ 4

Motivations for and barriers to donating sperm

Wanting to help people and empathising with involuntary childless people were motives for donation for more than three quarter of the respondents (Table 4). However, only one in four saw it as their duty to help people to have children. Significantly, more men who considered donating were motivated by the value of the donation for themselves. All four items that referred to a personal advantage or benefit to the donor (pass on my genes, free fertility test, financial compensation and satisfaction) were evaluated differently by those who considered donating and those who did not consider donating. The men who did not consider donating indicated that helping people and empathy with childless couples would be their major motivations. However, since they did not consider donating, these statements should rather be interpreted as what they believed should be the motivation of a donor.

Table 4.

Motivations for and barriers to donating sperm in students who considered donating versus those who did not consider donating and in students with or without a positive attitude towards sperm donation

| Considered donating (N = 319)a | Did not consider donating (N = 610)a | A positive attitudec (N = 798) | A neutral or negative attitudec (N = 135) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | |

| Motivations for donation: I would donate sperm…d | |||||

| because I believe it is my duty to help people | 102 (35.7)*** | 99 (18.6) | 188 (26.7)*** | 13 (11.5) | 201 (24.6) |

| to help people with a child wish | 264 (92.3)* | 465 (87.4) | 659 (93.5)*** | 70 (61.9) | 729 (89.1) |

| because I have experienced (in my immediate surroundings) what it means to be involuntarily childless | 46 (16.1) | 81 (15.2) | 120 (17.0)*** | 7 (6.2) | 127 (15.5) |

| because I empathise with couples having fertility problems | 216 (75.5) | 408 (76.7) | 570 (80.9)*** | 54 (47.8) | 624 (76.3) |

| to pass on my genes | 65 (22.8)*** | 72 (13.5) | 122 (17.3) | 15 (13.3) | 137 (16.8) |

| to know more about the quality of my sperm through the fertility test | 186 (65.0)*** | 233 (43.8) | 363 (51.5) | 56 (49.6) | 419 (51.2) |

| for the financial compensation | 170 (59.4)*** | 180 (33.8) | 308 (43.7) | 42 (37.2) | 350 (42.8) |

| because it would give me some satisfaction | 139 (48.6)*** | 126 (23.7) | 255 (36.2)*** | 10 (8.8) | 265 (32.4) |

| Barriers to donation: I would not donate sperm becausee | |||||

| I would have one or more children that I do not know | 111 (39.9)*** | 279 (53.7) | 313 (45.5)*** | 77 (70.0) | 390 (48.9) |

| there is a chance that children conceived with my sperm would trace me | 132 (47.5) | 239 (46.0) | 311 (45.2)* | 60 (54.5) | 371 (46.5) |

| there is a chance that my own (future) children and the children conceived with my sperm would accidently get in a relationship with each other | 57 (20.5) | 135 (26.0) | 157 (22.8)* | 35 (31.8) | 192 (24.1) |

| I would feel responsible for the wellbeing of the children | 89 (32.0)*** | 244 (47.1) | 270 (39.3)*** | 63 (57.8) | 333 (41.8) |

| my sperm could be used by lesbian couples | 12 (4.3)*** | 43 (8.3) | 34 (4.9)*** | 21 (19.3) | 55 (6.9) |

| my sperm could be used by single mothers | 18 (6.5)*** | 56 (10.8) | 47 (6.8)*** | 27 (25.0) | 74 (9.3) |

| I have other priorities | 84 (30.2)* | 203 (39.0) | 229 (33.3)*** | 58 (52.7) | 287 (36.0) |

| it does not interest me enough | 61 (21.9)*** | 193 (37.2) | 194 (28.2)*** | 60 (55.0) | 254 (31.9) |

| I do not have enough practical information about how to donate sperm (e.g. how to make an appointment, locations,…) | 141 (50.7) | 284 (54.8) | 369 (53.7) | 56 (51.4) | 425 (53.4) |

| I do not feel comfortable with the idea of donating sperm | 56 (20.1)*** | 205 (39.6) | 192 (27.9)*** | 69 (63.3) | 261 (32.8) |

| I would feel uncomfortable while donating sperm | 93 (33.5)*** | 229 (44.3) | 260 (37.8)*** | 62 (57.4) | 322 (40.5) |

| I think I am not (physically, genetically, emotionally) fit to donate | 50 (18.0) | 96 (18.5) | 128 (18.6) | 18 (16.5) | 146 (18.3) |

| I am afraid the tests would reveal problems with my sperm or genes | 65 (23.4) | 101 (19.5) | 150 (21.8) | 16 (14.7) | 166 (20.9) |

| I am afraid my partner would not agreef | 62 (50.8) | 105 (47.7) | 144 (47.2) | 23 (62.2) | 167 (48.8) |

| I do not feel like talking about this in my relationshipf | 35 (28.7)* | 87 (39.5) | 100 (32.8)** | 22 (59.5) | 122 (35.7) |

| I am afraid it would harm my relationshipf | 38 (31.1)* | 94 (42.7) | 107 (35.1)*** | 25 (67.6) | 132 (38.6) |

| I am afraid my (possible/future) partner would not agreeg | 45 (29.0) | 106 (35.6) | 125 (32.8) | 26 (36.1) | 151 (33.3) |

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. p value based on Chi2 test to compare the proportion of respondents (totally) agreeing between ‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’ (indicated in the column ‘considered donating’); and between ‘A positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’ (indicated in the column ‘A positive attitude’)

a4 missing cases

bRespondents answering ‘rather agree’ or ‘totally agree’ within each category (‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’; and ‘a positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’)

cAttitude scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7); positive: all students who scored ≤ 3; not positive: all students who scored ≥ 4

dMissing cases varied from 89 to 90

eMissing cases varied from 115 to 137

fOnly for respondents in a relationship (N = 342)

gOnly for respondents without partner (N = 453)

People with a positive attitude towards sperm donation scored significantly higher on all motivation items apart from three items with a self-benefit (passing on genes, fertility test and financial compensation). The positive attitude was mainly correlated with empathic feelings and the wish to help.

The highest scored barriers to donating (Table 4) were the lack of practical information and the fear that the partner would not agree. Almost 40% of the respondents feared that the donation might have a negative impact on their current or future relationship. Also, slightly more than 40% seemed to be deterred by a feeling of responsibility for the offspring. About half the students (48.9%) did not like the idea that they would have children they would not know. Students who considered donating differed significantly from those who did not on these two items, with the second group stating more often that they would feel responsible for the offspring and that they would not like the idea that they had children they would not know. Another element that was indicated by a large minority of the respondents was the feeling of discomfort: 32.8% would feel uncomfortable with the idea of donating and 40.5% would feel uncomfortable while donating. Students who did not consider donating reported these feelings up to about twice as much.

Men with a positive attitude towards sperm donation differed significantly from the men with a neutral or negative attitude on all barriers except five: fear of partner not agreeing, fear of future partner not agreeing, not having enough practical information, fear that the tests would reveal problems with their sperm or genes and belief that they are not suitable as a donor. This demonstrates that their overall attitude towards sperm donation is linked to a fairly consistent combination of objections to donation.

Although the condition of knowing the recipients or directing their sperm to certain groups of recipients was unimportant for most respondents, the possibility that their sperm would be used by single women and lesbian couples was nevertheless a barrier for around 20% of the men who were neutral or negative about sperm donation (numbers not shown in the table). 28.2% of this group also indicated that they would like to be able to decide who would be allowed to use their sperm.

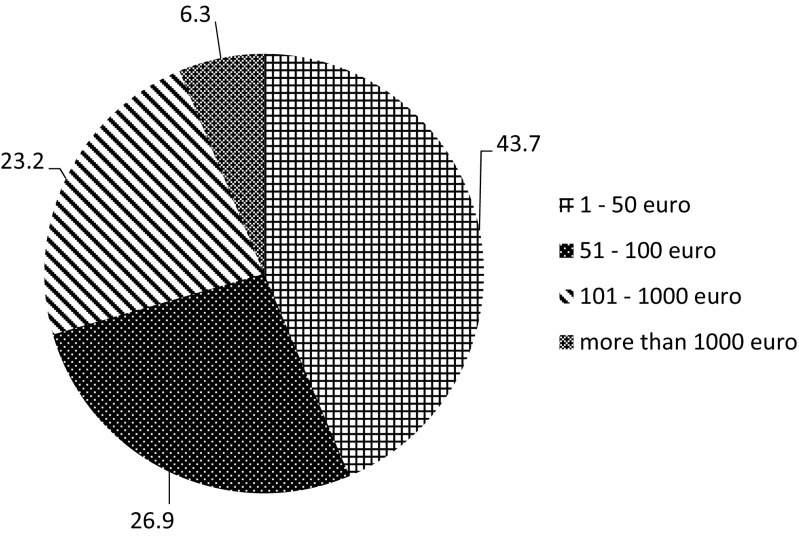

About 45% of the respondents believed that most men donate for the money (Table 2). In our sample, 43.4% indicated this motivation, going up to 59.5% of those who considered donating. On the question whether donors should receive financial compensation, 71.3% said yes, increasing to 83.6% in those who considered donating. In our study, 43.7% would donate for an amount between 1 and 50 € and 26.9% for an amount between 51 and 100 €. Students who considered donating more often agreed with this statement than those who did not consider donating. The majority of the respondents (71.4%) thought that sperm donors should receive financial compensation. Significantly, more students who considered sperm donation compared to those who did not consider donating thought that the donor should get compensation.

Men with a positive attitude towards donation significantly less often thought that donors should receive financial compensation compared to men with a neutral or negative attitude. Students who thought a sperm donor should get financial compensation were asked from what amount they themselves would be willing to consider donating sperm (Fig. 1). More than 40% of these students said 1 to 50 € would be enough, a little over a quarter would need 51 to 100 €, nearly a quarter would need up to 1000 € and a small number of respondents would not be convinced with less than 1000 €. When we calculated the mean amount that the students would like to receive in order to consider donation, we find that students who thought that it was appropriate to offer financial compensation for sperm donation would donate for 259 € while for those who did not consider donation, it would require a mean of 2401 € to review their intention.

Fig. 1.

Financial compensation: from what amount would students be willing to consider donating sperm? (N = 607)1 . Only answered by all respondents who think a sperm donor should get a financial compensation

Perceived social support and importance of social support

Social pressure to donate sperm was very low (3.7%): men clearly did not believe that their social environment thinks that they should donate sperm (Table 5). The respondents believed that less than half of the people who are important to them would support their decision to donate sperm: 50.2% of the students thought their friends would approve of this decision, 38.8% thought their partners would approve and 36.1% thought their family would. Significantly, more students who have considered donating believed that their friends would approve of them donating. At the same time, less than half (< 40%) would pay much attention to the opinion of their friends and family. The perceived attitude of their partner clearly weighs heavier in this decision than that of friends and family. More than 90% thought the opinion of their partner was rather or very important. However, less than 40% believed that their partner would support them. A large majority would inform their partner and would involve the partner in the decision. Possible future partners would less often be informed than current partners. More than one in five would not inform anyone about their donation.

Table 5.

Perceived social support and importance of social support in students who considered donating versus those who did not consider donating and in students with or without a positive attitude towards sperm donation

| Considered donating (N = 319)a | Did not consider donating (N = 610)a | A positive attitudec (N = 798) | A neutral or negative attitudec (N = 135) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | |

| I believe that important people in my environment (friends, family, partner) think that I should donate sperm | 20 (6.9)*** | 11 (2.0) | 28 (3.9) | 3 (2.6) | 31 (3.7) |

| If I would donate sperm, … | |||||

| my partner would support my decisiond | 55 (42.3) | 84 (36.8) | 131 (41.1)** | 8 (20.5) | 139 (38.8) |

| my family would support my decision | 114 (39.3) | 186 (34.4) | 280 (39.1)*** | 20 (17.4) | 300 (36.1) |

| my friends would support my decision | 175 (60.3)*** | 242 (44.7) | 387 (54.1)*** | 30 (26.1) | 417 (50.2) |

| I would inform my partnerd | 110 (84.6) | 207 (90.8) | 283 (88.7) | 34 (87.2) | 317 (88.5) |

| I would involve my partner in the decision makingd | 99 (76.2)* | 193 (84.6) | 256 (80.3)* | 36 (92.3) | 292 (81.6) |

| I would inform a future partner about this | 183 (63.1) | 371 (68.6) | 481 (67.2) | 73 (63.5) | 554 (66.7) |

| I would not tell anyone | 68 (23.4) | 120 (22.2) | 150 (20.9)* | 38 (33.0) | 188 (22.6) |

| If you would donate sperm, how important would you find the opinion of… | |||||

| your partner?d | 115 (88.5) | 212 (93.0) | 292 (91.5) | 35 (89.7) | 327 (91.4) |

| your family? | 96 (33.1)* | 220 (40.7) | 258 (36.0)* | 58 (50.4) | 316 (38.0) |

| your friends? | 94 (32.4) | 191 (35.3) | 244 (34.1) | 41 (35.7) | 285 (34.3) |

Number of missing cases for all items was 102

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. p value based on Chi2 test to compare the proportion of respondents (totally) agreeing between ‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’ (indicated in the column ‘considered donating’); and between ‘A positive attitude’ and ‘A neutral or negative attitude’ (indicated in the column ‘A positive attitude’)

aNumber of missing cases: 4

bRespondents answering ‘rather agree’ or ‘totally agree’ within each category (‘considered donating’ and ‘did not consider donating’; and ‘a positive attitude’ and ‘a neutral or negative attitude’), except for the last three rows. There, the percentage stands for the percentage of students answering ‘rather important’ or ‘very important’

cAttitude scored on a 7-point semantic differential scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (7); positive: all students who scored ≤ 3; not positive: all students who scored ≥ 4

dOnly for students with partner (N = 358)

Men with a positive attitude towards sperm donation expected a significantly more positive reaction from their social network (family, friends and partner) (Table 5). They also would more often involve their partner in the decision-making and less often keep their donor status a secret. People with a neutral or negative attitude more often cared about the opinion of their family than men with a positive attitude (60.4 vs. 36%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The wish for information exchange between donor and recipients in this study was limited in two directions: neither did potential donors want to obtain much information on children and recipients, nor did they want to provide much information about themselves to children and recipients. In our study, students showed relatively little interest in the children. In the Cook and Golombok study (1995) [8], both donors and non-donors similarly had little interest in obtaining information about the offspring. In the Serbian study, however, 32.7% indicated a wish to meet the offspring in the future [4].

Regarding the information provided to the children, about two thirds did not want any information given about themselves and one in four would accept their name to be released. In an older Belgian study of 296 non-donors, older non-donors had more objections against meeting their possible donor offspring and were less willing to pass on their name to the children. Non-donors with children were less prepared to give their name to the offspring and they also objected to later contact [9]. In the Cook and Golombok study (1995) [8], only 10% of the non-donors believed that identifying information should be given to the child. In the study of Lui and Weaver (1996) [10], 60.7% of the students and 63.3% of the fathers would not mind if their physical characteristics, attitudes and personal interests were given to the offspring. When identifying information was considered, the position changed completely: 80.4% of the students and 84.1% of the fathers would not donate without a guarantee of anonymity. Also in a study in Nigeria [5], 90% of the men willing to donate objected to their identities being disclosed to the recipient couples. Finally, the respondents in the Fishburn Hedges/ICM Research study in the United Kingdom (2004) [11] were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed or disagreed to the statement ‘If I was to donate sperm, I would not mind my details being made available to the child when they are 8’: 16% agree strongly, 22% agree, 18% disagree and 37% strongly disagree. The main exception was the Serbian study where 70.2% of the respondents said yes when asked if they would agree if the child conceived through their sperm wishes to meet them when he/she comes of age. Moreover, 20% was unsure and only 9.8% said no. No explanation was offered for this finding. Although the studies are limited, most studies confirm that only a minority of the non-donors would accept to be identifiable in case they would donate.

Participants in our study showed generally little interest in the recipients as they did not want to know much about the families. In Lui and Weaver study (1996) [10], around 20% of the non-donor students and fathers would like some description of the families. In the same study, 30.4% of the students and 13.4% of the fathers would have liked to have a say in the selection of the recipients. Still, 37.5% of the students and 59.1% of the fathers preferred that their semen would not be used for single women.

Within their social network, the potential donors’ partner was given a special status. Contrary to some other studies, our respondents were generally uncertain about the views and position of their partner. In one study, 66.1% of the students and 63.8% of the fathers indicated that they felt quite comfortable discussing the fact that they were a donor with their wife or partner and friends [10]. In Serbia, around two thirds of the men would inform their partner and their closest friends about their donation and one in two would tell their family [4].

As mentioned in the introduction, very little is known about the attitude of the general population regarding sperm donation. Unpublished research commissioned by the Department of Health in the UK [11] in 2004 (total sample n = 301, aged between 18 and 54) indicated that 10% would definitely consider donating sperm in order to help infertile couples, 35% may consider this, 22% would not consider this and 28% would under no circumstances consider doing this. Another study found that 42% of the general public and 60% of the students would donate sperm [12]. The Canadian survey among 3500 persons found that 26% would be very or somewhat likely to donate sperm [13]. In general, the studies show a fairly large group of men willing to donate. We know, however, from the experience of sperm banks that few actually come forward. How to explain the discrepancy?

Very recently, the European Commission published a Eurobarometer survey on the attitude of the European population towards donation of tissues and cells [14]. This survey also included donation of sperm and eggs. They found that in Europe (28 member states) 24% of men were prepared to donate sperm. The Eurobarometer study distinguished four categories of respondents: 1% who donated and would donate again, 1% who donated and would not donate again, 22% who had not donated but would be prepared to donate in the future and 62% who had not donated and would not be prepared to donate in the future. Around 13% did not know. When the percentage of men being prepared to donate in the future is correlated with some biographic characteristics the percentage was higher for men between 15 and 24 (34%) and between 25 and 39 (29%). Moreover, students (35%) and unemployed respondents (32%) also were more prepared to donate in the future. This study also found that around 30% of Belgian men (compared to a mean of 24% in Europe) were willing to donate in the future. This percentage is comparable to the 34% who did not donate but considered donating in our study. Also, in our study 1.8% of the respondents had donated in the past (those men were excluded from further analyses), compared to 2% in the Eurobarometer study.

One of the main motivators for students to donate in our study was money. Most men who thought that donors should receive financial compensation had amounts in mind that correspond with the actual practice in Belgium. Most clinics pay between 50 and 100 € per sample [15]. About 70% of the students would donate for the amounts paid by the clinics today. However, we did not ask the students how much they believed sperm donors received so they may not have been aware of that.

There is a strong discrepancy between our findings and the Belgian data from the Eurobarometer survey regarding acceptable compensation for tissue donation. In that study, free testing was considered acceptable by 44% of the respondents. However, cash amounts additional to the reimbursement of the cost were approved by only 13%. In other studies, the majority of the non-donors were attracted by the money [8, 16]. Also in the Lyall et al. (1998) study [12], 67% of the students but only 39% of the general public were in favour of payment. Among those who would be prepared to donate, 70% of the students and 33% of the general public said that if they were paid, they were more likely to donate. In the study of Lui and Weaver (1996) [10], 44.6% of the non-donor students and 25% of the non-donor fathers would not donate if they would not be paid. When the men in the Fishburn Hedges/ICM Research study (2004) [11] were asked to select the one reason which would most motivate them to donate sperm, 38% indicated having friends or family who have suffered from infertility, 29% the desire to ‘do good’ and 11% pointed to the financial compensation. In the older Belgian study, fathers and older men attached less importance to financial remuneration (9).

Although our study does not allow us to pinpoint the most important barrier to donation, it seems that the fear for the effect on their relationship and the negative reaction from the social environment play a role. This contrasts with the Cook and Golombok study (1995) [8] where non-donors had relatively few concerns about their social environment. Only 15% were worried about what their parents would think if they knew and about 29% about what their current or future partner might feel. They had greater worries (38%) about how they themselves would feel about the offspring in the future and about how their own child(ren) might feel.

When asked whether important people in their lives thought that they should donate sperm, only 3.8% agreed. Sperm donation is seen as supererogatory: an act that is good and for which a person can be praised but that is beyond a person’s duty. This structure explains why on the one hand, 85% of the men believed that sperm donation is a good way to help childless couples and on the other hand only 25% believed that they have a duty. This also fits with the very small group (3.8%) of men who indicated that they would regret it if they would not donate. It could be argued that one explanation for not donating is inertia and disinterest. In the Cook and Golombok (1995) [8] study, 42% of those who had considered donating but had not donated explained this mainly through a lack of motivation rather than by some serious issues related to the donation. We found lower percentages but still around one in four: 29.9% of those who had considered donating had other interests and 21.7% was not interested enough. It seems that at least for one in four men, a powerful incentive is needed to overcome this inertia. So the absence of a will to donate seems to be due to a combination of three factors: a relatively strong pull not to donate based on the expected negative reaction of their social environment, the absence of a positive push to donate given the lack of a sense of obligation and a lack of interest.

This study is based on a large but non-representative sample of students. Therefore, we cannot generalise our results to all college or university students nor to all men who would qualify as sperm donors. The absence of a response rate is a clear limitation of the study. Our dropout analysis showed that those who started but did not complete the questionnaire were in general more negative about sperm donation than those who continued, which points to a possible overvaluation of sperm donation in the sample studied. It is to be expected that those who filled out the questionnaire were more interested in the topic than those who did not participate at all. Moreover, social desirability may have influenced the answers.

Conclusion

About one third of the students who had never before donated sperm would consider doing so and 85% of the students thought positively about sperm donation. The results of our survey indicate that a decisive factor in the men’s attitude might be the view of sperm donation as a supererogatory act: it is good if a man donates but no man is under an obligation to donate. This view, combined with very low social pressure, results in a minimal push to donate. Perceived negative views in their social environment, especially from the partner, are then sufficient to deter men from donating. It would be possible to introduce a strong incentive, for instance in monetary terms, but this study indicates that the effect on a donor pool consisting of students would be limited. It seems unlikely that very specific actions will have a large impact on recruitment. A possible long-term solution might be to take measures to change the general perception of sperm donation in the same direction as blood donation: a helpful act for which one should be praised. Such measures should be framed in a broader context of acceptance of gamete donation and a general reduction of the importance attached to genetic parenthood.

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by the Research Fund of Ghent University, Belgium.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Hudson N, Culley L, Rapport F, Johnson M, Bharadwai A. “Public” perceptions of gamete donation: a research review. Public Underst Sci. 2009;18:61–77. doi: 10.1177/0963662507078396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Broeck U, Vandermeeren M, Vanderschueren D, Enzlin P, Demyttenaere K, D'Hooghe T. A systematic review of sperm donors: demographic characteristics, attitudes, motives and experiences of the process of sperm donation. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:37–51. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lampiao F. What do male students at the college of medicine of the university of Malawi say about semen donation? TAF Prev Med Bul. 2013;12:75–78. doi: 10.5455/pmb.1-1333353810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedrih A, Hedrih V. Attitudes and motives of potential sperm donors in Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2012;69:49–57. doi: 10.2298/VSP1201049H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onah HE, Agnbata TA, Obi SN. Attitude to sperm donation among medical students in Enugu, South-Eastern Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:96–99. doi: 10.1080/01443610701811928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ide L, Verheecke T, Decleer W, Osmanagaoglu K. Opinieonderzoek bij potentiële spermadonoren naar het mogelijk toekomstig gedrag van dergelijke donoren indien de Belgische wetgeving de anonimiteit van de donor zou opheffen. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2015;71:1229–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennings G. Belgian law on medically assisted reproduction and the disposition of supernumerary embryos and gametes. Eur J Health Law. 2007;14:251–260. doi: 10.1163/092902707X232971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook R, Golombok S. A survey of semen donation: phase II - the view of the donors. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:951–959. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heurckmans N, Pennings G, Sabbe K, Baetens P, Rigo A, Guldix E, et al. The attitude towards offspring by donor candidates and non-donors: the influence of payment, age, and fatherhood. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(suppl. 1):199. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lui SC, Weaver SM. Attitudes and motives of semen donors and non-donors. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:2061–2066. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishburn Hedges/ICM, Donation of Eggs and Sperm UK Survey. 2004. Unpublished results.

- 12.Lyall H, Gould GW, Cameron IT. Should sperm donor be paid? A survey of the attitudes of the general public. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:771–775. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies Canada . Proceed with care: final report of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies. Ottawa: Canadian Government Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eurobarometer Blood and cell and tissue donation . Special Eurobarometer 426/Wave EB82.2 – TNS Opinion & Social. Brussels: European Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thijssen A, Dhont N, Vandormael E, Cox A, Klerkx E, Creemers E, et al. Artificial insemination with donor sperm (AID): heterogeneity in sperm banking facilities on a single country (Belgium) Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2014;6:57–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emond M, Scheib JE. Why not donate sperm? A study of potential donors. Evol Hum Behav. 1998;19:313–319. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]