Abstract

Purpose

Oocyte and/or embryo cryopreservation after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) represents the most established method for female fertility preservation (FP) before cancer treatment. Whether patients suffering from malignancies, candidates for FP, have a normal ovarian capacity to respond to stimulation is controversial. Reduced responsiveness of antral follicle to exogenous FSH might be at play. The percentage of antral follicles that successfully respond to FSH administration may be estimated by the follicular output rate (FORT), which presumably reflects the health of granulosa cells. The present study aims at investigating whether the FORT differs between Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and breast cancer (BC) patients.

Methods

Forty-nine BC and 33 HL patient candidates for FP using oocyte vitrification following COH were prospectively studied. FORT was calculated by the ratio between the pre-ovulatory follicle count (16–22 mm) on the day of oocyte triggering × 100/antral follicle count before initiation of the stimulation.

Results

Overall, women in the HL group were younger in comparison with BC patients (26.4 ± 3.9 vs 33.6 ± 3.3 years, p < 0.0001, respectively). The FORT was significantly decreased in patients with HL when compared with BC group (27.0 ± 18.8 vs 39.8 ± 18.9%, p = 0.004, respectively), further leading to a comparable number of oocytes vitrified (10.8 ± 5.9 vs 10.2 ± 7.7 oocytes, p = 0.7, respectively).

Conclusion

The present findings indicate that the percentage of antral follicles that successfully respond to FSH administration is reduced in HL when compared to BC patients, supporting the hypothesis of a detrimental effect of hemopathy on follicular health. In vitro experimentations might provide additional data to confirm this hypothesis.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, Fertility preservation, Follicular Output Rate

Introduction

Over the past decades, advances in the management of oncological diseases have led to an increase in survival rates of children and young adults suffering from cancer [1]. However, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, often used to cure malignancies, may lead to the destruction of the follicular stockpile, resulting in a dramatic reduction of the fertility potential. The question of fertility preservation (FP) in young cancer patients has become a major issue in the care-personalized path. Indeed, many FP techniques have been developed to enable cancer survivors to improve their possibility of becoming genetic parents after healing [2]. Despite improvements in ovarian tissue cryopreservation, the vitrification of fertilized or unfertilized oocytes recovered after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) before cancer therapy still represents the most established and efficient method for preserving female fertility [2, 3].

Whether cancer patients have a normal ovarian capacity to respond to stimulation is controversial. Indeed, it is conceivable that the oncological status may, by itself, have a negative impact on the ability of granulosa cells of small antral follicles to respond to exogenous FSH [4]. Although some studies have reported lower ovarian response in women suffering from malignancies [4, 5], other investigations failed to find any difference [4, 6].

Actually, breast cancer (BC) and lymphomas represent two of the most recognized indications for FP in young adults. However, the impact of these two clinical situations on patients’ general health status differs dramatically. Indeed, while women suffering with BC usually show normal general condition, those diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) often present with fever, weight loss, and tiredness.

Several lines of evidence indicate the follicular output rate (FORT), calculated from the ratio between the number of pre-ovulatory follicles obtained in response to FSH administration and the preexisting pool of small antral follicles, may represent an interesting tool for the evaluation of antral follicle responsiveness to exogenous FSH, independently of the follicular cohort size before treatment [7, 8].

Therefore, the present investigation aims at evaluating COH outcomes as well as the sensitivity of small antral follicles to exogenous FSH, assessed by the FORT, in HL or BC candidates for oocyte vitrification.

Patients and methods

Patients

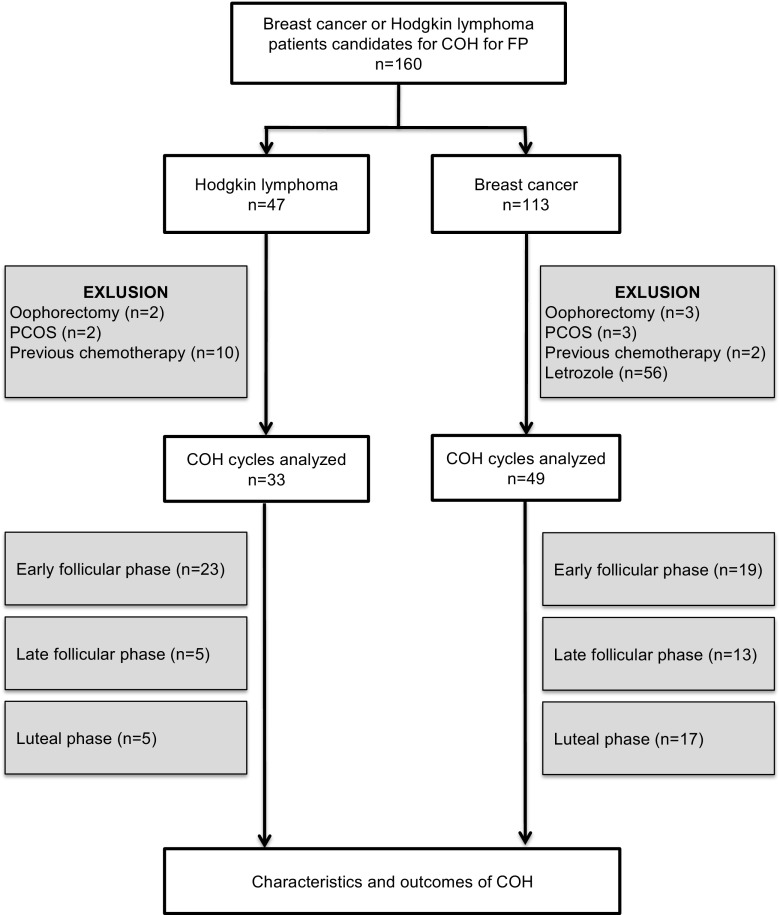

One hundred and sixty patients presenting HL or BC, 18 to 40 years of age, undergoing COH for oocyte vitrification between July 2013 and April 2015 were included in the present study (Fig. 1). All of them met the following inclusion criteria: (i) regular menstrual cycles lasting between 25 and 35 days; (ii) both ovaries present, deprived of morphological abnormalities, adequately visualized in transvaginal ultrasound scans; (iii) indication of FP for HL or BC; (iv) conventional ovarian hyperstimulation without aromatase inhibitors nor tamoxifen intake. Exclusion criteria were the following: (i) history of ovarian surgery or gonadotoxic treatment; (ii) current or past diseases affecting gonadotropin or sex steroid secretion, clearance, or excretion; (iii) polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS); (iv) patients having received aromatase inhibitors (Letrozole) or tamoxifen during COH.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation protocol

In both groups, ovarian stimulation was performed using GnRH antagonist protocol and administration of recombinant FSH (recFSH; Gonal-F®, Merck-Serono Pharmaceuticals, France). Exogenous FSH therapy was initiated at a dosage ranging from 150 to 450 IU/day, S.C., calculated from patient’s age, body mass index (BMI), AMH and AFC.

All patients suffering from BC underwent tumorectomy or mastectomy before starting the FP process using COH. Moreover, oncologist agreement and authorization for COH was obtained systematically.

Since FP often requires emergency treatments, random-start protocols of ovarian stimulation were specifically performed according to the phase of the menstrual cycle [8, 9]. Early follicular phase was defined by serum progesterone levels < 1.5 ng/mL and absence of antral follicle > 12 mm in diameter on ultrasound scan. In these situations, recombinant FSH was administered for at least 5 days at initial dosage. From the 6th day of recFSH therapy onwards, daily recFSH doses were adjusted according to serum estradiol levels and/or the number of growing follicles. Starting on stimulation day 6, all patients received 0.25 mg GnRH antagonists (Ganirelix, Orgalutran® 0.25 mg, S.C., MSD Pharmaceuticals, France).

Luteal phase was defined by serum progesterone levels > 1.5 ng/mL. In these patients, recombinant FSH was administered in combination with GnRH antagonists for 5 days and further adjusted according to E2 levels and/or the number of growing follicles.

In all patients, final oocyte maturation was obtained using either recombinant hCG (Ovitrelle® 250 mcg; Merck-Serono Pharmaceuticals, 0.25 mg S.C.) or GnRH agonist (triptorelin 0.1 mg, Decapeptyl®, Ipsen Pharmaceuticals, 0.2 mg, S.C.) as soon as ≥ 4 pre-ovulatory follicles (16–22 mm in diameter) were observed. In case of poor response, ovulation triggering was performed even when at least one pre-ovulatory follicle was present.

Patients treated with Letrozole during COS were excluded from the study. Nevertheless, 36 patients with estrogen-sensitive tumors were not on Letrozole and then included in this study. Indeed, Letrozole is off label in this indication in our country. Therefore, it could not be prescribed in candidates for fertility preservation except in research programs. Such a program has been obtained in 2015. Before that date, all patients underwent conventional ovarian stimulation, even when an estrogen-sensitive tumor was diagnosed.

Metaphase II oocytes (MII), confirmed by the presence of one polar body, were vitrified as previously described [10].

Ultrasound scans and hormonal measurements

Before oncofertility counseling and whatever the phase of the menstrual cycle (d0), a transvaginal ovarian ultrasound scan for follicle measurements as well as blood sampling for serum AMH and progesterone levels assessment were performed for each woman in order to estimate ovarian reserve and the phase of the cycle. Further, each patient underwent routine ovarian ultrasound scan and blood work for monitoring COH, until the day of ovulation triggering (dOT).

Ovarian ultrasound scans were performed using a 5.0–9.0 MHz multi-frequency transvaginal probe (Voluson 730 Expert®, General Electric Medical Systems, Paris, France) by two operators, who were blinded to the diagnosis and the results of hormone assays The objective of ultrasound examination was to evaluate the number and sizes of small antral follicles. All follicles measuring 3 to 22 mm in mean diameter (mean of two orthogonal diameters) in each ovary were counted. Only antral follicles < 8 mm were considered for AFC at d0 and follicles between 16 and 22 mm on dOT were considered for pre-ovulatory follicle count (PFC). To optimize the reliability of ovarian follicular assessment, the ultrasound scanner was equipped with a tissue harmonic imaging system, which allowed improved image resolution and adequate recognition of follicular borders. Intra-analysis coefficients of variation (CV) for follicular and ovarian measurements were < 5% and their lower limit of detection was 0.1 mm.

Serum progesterone (P4) and 17β-Estradiol (E2) levels were determined by an automated multi-analysis system using an electro-chemi-luminescence detection technology (Cobas 6000, Roche, Meylan France). For P4, lower detection limit was 0.030 ng/mL, linearity up to 60 ng/mL, and intra- and inter-assay CV were 2.9 and 4.8%, respectively, as determined by the manufacturer. For E2, lower detection limit was 5 pg/mL, linearity up to 3000 pg/mL, and intra- and inter-assay CV were 6.7 and 10.6%, respectively, as determined by the manufacturer.

Serum AMH was measured by an enzymatically amplified two-site immunoassay (AMH Gen II ELISA; Beckman Coulter). All steps of procedure were conducted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The lower detection limit of the assay was 0.1 ng/mL. The mean inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 5.6%, and the mean intra-assay CV was 4.0%.

Calculation of FORT and estimation of per-follicle E2 production

The FORT was calculated by the ratio between the PFC on dOT × 100/AFC at d0. The choice of considering only 16–22 mm follicles for the calculation of FORT was used in previous investigation. The FORT aims to represent a new parameter for discriminating small antral follicles that were the most FSH-responsive [8].

Per-follicle E2 production on dOT was estimated by the ratio between serum E2 levels on dOT /total number of follicles > 12 mm in diameter on dOT.

Statistical analysis

The measure of central tendency used was the mean and the measure of variability was the standard deviation (SD) for parametrical data. Differences between FP and control groups were evaluated with Student’s t test with Welsh correction or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon, when appropriate. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The present investigation was approved by the Local Ethic Committee, Comité d’Ethique Local pour la Recherche Clinique des HUPSSD Avicenne, Jean Verdier et René Muret (CLEA-2015-028).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

One hundred and thirteen women were suffering from non-metastatic BC with an indication of adjuvant chemotherapy following the surgical treatment (Fig. 1). Among these patients, 49 patients were included in the study. Thirty-six tumors showed expression of estrogen and/or progesterone receptors, 13 tumors were triple-negative. The majority of breast cancer was classified T1 or T2 according to TNM classification. Forty-seven women were referred for FP before chemotherapy for HL. Among them, 33 were included in the present investigation. According to Ann Arbor classification, stages I, II, III, and IV of the disease were diagnosed in 3, 14, 2, and 8 patients, respectively.

Women in the HL group were significantly younger than BC patients (26.4 ± 3.9 vs. 33.6 ± 3.3 years, p < 0.0001, respectively). Although patients suffering from hematologic malignancy showed higher mean value of AFC (22.7 ± 9.4 vs. 16.4 ± 9.5 follicles, p = 0.005, respectively), their mean serum AMH level did not differ significantly when compared with BC patients (3.1 ± 2.5 vs. 2.9 ± 2.2 ng/mL, p = 0.6, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma n = 33 |

Breast cancer n = 49 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 26.4 ± 3.9 | 33.6 ± 3.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Med (min-max) | 25.9 (18–34) | 33.5 (25–40) | |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 23.3 ± 6.1 | 23.4 ± 4.7 | 0.8 |

| No of antral follicle on d0 (n) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 22.7 ± 9.4 | 16.4 ± 9.5 | 0.005 |

| Med (min-max) | 21.5 (8–44) | 14 (4–48) | |

| Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels (ng/ml) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 2.5 | 2.9 ± 2.2 | 0.6 |

| Med (min-max) | 2.7 (0.7–14) | 2.4 (0.7–9.8) | |

| Stadification (Ann Arbor/TNM) | Stage I: 3 | T1 25 N0 40 M0 49 | |

| Stage II: 14 | T2 20 N1 5 | ||

| Stage III: 2 | T3 1 N2 1 | ||

| Stage IV: 8 | T4 0 N3 0 | ||

| NA: 6 | NA 3 NA 3 | ||

Student’s t test

SD standard deviation, NA non-available

aMean ± SD

COH characteristics and outcomes

Overall, with similar FSH starting doses and total amount of exogenous gonadotropins, the mean number of eggs recovered and MII oocytes finally obtained did not differ between HL and BC patients (15.0 ± 7.2 vs. 12.9 ± 8.9 oocytes, p = 0.2; 10.8 ± 5.9 vs. 10.2 ± 7.7 MII oocytes, p = 0.7). Interestingly, maturation rate was lower in HL patients (71.3 ± 16.4 vs. 79.7 ± 19.2%, p = 0.04) as well as FORT values (27.0 ± 18.8 vs. 39.8 ± 18.9%, p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Table 2.

COH outcomes

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma n = 33 |

Breast cancer n = 49 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting dose of gonadotropins (IU)a | 258 ± 80 | 280 ± 84 | 0.3 |

| Total dose of gonadotropins (IU)a | 3062 ± 1551 | 2893 ± 1245 | 0.6 |

| Duration of stimulation (days)a | 10.5 ± 2.2 | 10.4 ± 2.7 | 0.4 |

| Serum E2 levels on dOT (pg/ml)a | 1185 ± 756 | 1613 ± 889 | 0.02 |

| Follicles > 16 mm on dOT | 6.0 ± 4.2 | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 0.7 |

| Per-follicle E2 levels on dOT (pg/ml/follicle)a | 87.4 ± 60.1 | 155.1 ± 86.0 | <0.0001 |

| No of oocytes recovered (n) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 15.0 ± 7.2 | 12.9 ± 8.9 | 0.2 |

| Med (min-max) | 14 (1–36) | 10 (3–38) | |

| No of metaphase II oocytes (n) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 10.8 ± 5.9 | 10.2 ± 7.7 | 0.7 |

| Med (min-max) | 10 (1–28) | 8 (1–35) | |

| Maturation rate (%) | 71.3 ± 16.4 | 79.7 ± 19.2 | 0.04 |

| FORT* (%)a | 27.0 ± 18.8 | 39.8 ± 18.9 | 0.004 |

Student’s t test

Per-follicle E2 levels: serum E2 levels on day OT × 100/no of follicles > 12 mm in diameter. Follicular output rate: no of follicles > 16 mm on dOT × 100/no of antral follicles on d0

SD standard deviation, FORT follicular output rate

aMean ± SD

In the BC group, FORT did not differ when ovarian stimulation was started in the follicular or the luteal phase (41.8 ± 19 vs. 38 ± 18.8% respectively, p = 0.5). In addition, similar results were also observed in HL group (24.4 ± 16.5 vs. 33.3 ± 23.2% respectively, p = 0.3). Finally, all parameters of ovarian stimulation and outcomes were comparable whatever the phase of the cycle at which the treatment was started (data not shown).

HL patients showed significantly reduced E2 on dOT and per-follicle E2 production on dOT in comparison with BC patients (1185 ± 756 vs. 1613 ± 889 pg/mL, p = 0.02 and 87.4 ± 60.1 vs. 155.1 ± 86.0 pg/mL/follicle, p < 0.0001 respectively) (Table 2).

In the HL group, patients with localized disease (stages I and II of Ann Arbor classification) had the same basic characteristics and ovarian stimulation outcomes as women presenting with disseminated disease (stage III and IV of Ann Arbor classification) (data not shown).

Discussion

The central finding of the present investigation is the variable capacity of small antral follicles to respond to exogenous FSH according to the type of malignancy. Our results suggest that the Hodgkin status may, by itself, alter the follicular responsiveness to exogenous FSH. Indeed, despite higher AFC and comparable stimulation protocol and FSH doses, women suffering from HL unexpectedly showed similar number of MII oocytes vitrified when compared with BC women.

As expected according to epidemiological data, patients in the HL group were younger than BC patients. Evidence indicates that IVF successes are strongly correlated with age in healthy patients. These data might be extrapolated this to candidates for FP in contexts of malignant diseases. However, such data are still lacking due to the low number of patients having used their frozen eggs. Moreover, in healthy patients, the success rates not only depend on age but also on the number of cryopreserved oocytes.

The influence of cancer status on ovarian response to stimulation remains ill established. Indeed, many authors have pointed out the need for higher amounts of exogenous FSH and a reduced number of oocyte recovered in cancer patients seeking FP when compared with infertile controls, suggesting altered response to gonadotropins and/or poorer follicular competence [4, 5, 11–13]. Conversely, recent data failed to show any difference in ovarian response to stimulation between cancer patients and age-matched control subjects [6, 14–22].

The possible influence of the type of malignancy on COH outcomes is still matter of debate [22, 23]. Recently, Quinn et al. show that ovarian stimulation outcomes are similar in patients with a new diagnosis of breast cancer and patients undergoing elective fertility preservation [20]. Otherwise, the duration of stimulation has been reported to be longer in women with hematologic diseases when compared to those with gynecologic or breast cancer, even though the final number of oocyte recovered was similar in all groups [24]. Moreover, Lawrenz et al. showed that Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas were associated with reduced oocyte yield in comparison to BC [25]. In this study, lower serum AMH levels in women with hematologic diseases may explain these results [25].

However, the majority of these studies are limited by small sample sizes and use of different COH protocols. In addition, the overall results of ovarian stimulation were not analyzed regarding the baseline markers of ovarian reserve, in particular the precise number of antral follicles potentially responsive to FSH. As a consequence, the conclusions drawn should be taken with caution. It is, however, noteworthy that the intensity of ovarian response to stimulation is a function not only of the inherent sensitivity of antral follicles to FSH but also of the pretreatment size of the antral follicle pool, estimated by the AFC and serum AMH levels [26, 27]. Indeed, women with a large number of small antral follicles tend to produce, in response to FSH, more mature follicles and fertilizable eggs than those having a reduced count of small antral follicles.

To quantify follicle responsiveness to exogenous FSH, instead of merely reckoning the number of follicles undergoing pre-ovulatory maturation, we used the FORT index. This measure has the advantage of being independent of the AFC before FSH administration allowing a better understanding of the capacity of these follicles to respond to ovarian stimulation [7, 8, 28]. In infertile patients, candidates for IVF, FORT has been negatively and independently related to serum AMH levels and was reported as a qualitative reflector of ovarian follicular competence [6, 7]. We used for the first time this index in a context of oncofertility and found dramatically reduced values in HL when compared with BC. Importantly, the present results were obtained in patients with similar COH protocols. Indeed, conversely to previous studies comparing ovarian response to stimulation in HL and BC patients, we decided not to include women having received aromatase inhibitors or tamoxifen concomitantly to exogenous FSH in order to limit bias related to endogenous FSH release. Our findings may have important consequences on the future use of oocytes vitrified in hematologic patients. Indeed, evidence indicates that in an infertile population irrespective of age and absolute pre-COH AFC and post-COH PFC, patients endowed with a larger proportion of FSH-responsive antral follicles were more prone to become pregnant after IVF. Thus, scant responsiveness of antral follicles to exogenous FSH might reveal some degree of follicle/oocyte dysfunction [29, 30]. In addition, the reduced E2 production per follicle > 12 mm in HL patients may reinforce this hypothesis. Indeed, reduced serum E2 levels at the end of COH may involve alteration in LH secretion or action, or a negative effect of HL status on granulosa cell competence. Increased catabolic state, malnutrition, and stress often present in patients suffering from cancer may affect the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and therefore E2 production [31, 32]. However, since all patients included in the present study underwent COH using GnRH antagonists, LH levels were dramatically low, making LH hypothesis unlikely. As a consequence, it is plausible that alterations in granulosa cell function related to unknown factors associated with HL may be at play. These cell dysfunctions may represent early sign of follicular alteration that could explain the lower ovarian response to exogenous FSH reported in some studies [4, 5, 11–13].

Yet, we assume that the FORT presents inherent limitations [8]. First, this index is based on ultrasound evaluation, which is a subjective operator-dependent exam. Secondly, FORT supposes that just small antral follicles (3–8 mm at d0) respond coordinately to FSH while it is possible that differences exist with the FSH-driven growth according to their sizes [33].Moreover, FORT measurement assumed that on dOT, only 16–22 mm follicles effectively responded to FSH. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that smaller follicles also presented some degree of FSH responsiveness [33]. However, a major limitation may be represented by the use of random-start GnRH antagonist protocols in cancer patients [9]. ndeed, on the one hand, when COH is started during late follicular phase, some follicles are above the diameter of 8 mm on the day of evaluation of AFC (d0). Since larger follicles may be endowed with a higher concentration of FSH receptors, they may display increased responsiveness to this gonadotropin. In order to avoid this bias, we did not consider antral follicles >8 mm the day of AFC evaluation (d0) and for the FORT calculation. On the other hand, COH initiated during the luteal phase might be negatively impacted by both high level of circulating progesterone and the immediate co-administration of GnRH antagonists with exogenous FSH. Nevertheless, in each group, FORT remained comparable whatever the phase of the cycle at which ovarian stimulation was started. In agreement with our results, studies having analyzed the outcome in random-start protocols in comparison with conventional treatments, did not find differences in terms of number of matures oocytes obtained [34]. Thus, the presence of corpus luteum or luteal phase progesterone levels did not seem to adversely affect synchronized follicular development. Moreover, due to the retrospective nature of the work and to the relatively low sample size, these results need to be confirmed. At least, FORT has never been evaluated based on age. As HL patients were younger than BC patients, we cannot exclude that it might have directly impact follicle responsiveness to FSH.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that antral follicle responsiveness to FSH, as far as it is measurable by FORT, may be differentially influenced by the type of malignancy in young candidates for FP. Indeed, women diagnosed with HL may be less prone to respond to ovarian stimulation in comparison with BC patients. This difference might reveal some degree of follicle/oocyte dysfunction, as suggested by the reduced per-follicule E2 production at the end of ovarian stimulation. In vitro experimentations might provide additional data to confirm this hypothesis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1214–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee opinion No. 584: oocyte cryopreservation. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:221–222. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000441355.66434.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedler S, Koc O, Gidoni Y, Raziel A, Ron-El R. Ovarian response to stimulation for fertility preservation in women with malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingo J, Guillén V, Ayllón Y, Martínez M, Muñoz E, Pellicer A, et al. Ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in cancer patients is diminished even before oncological treatment. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:930–934. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardozo ER, Thomson AP, Karmon AE, Dickinson KA, Wright DL, Sabatini ME. Ovarian stimulation and in-vitro fertilization outcomes of cancer patients undergoing fertility preservation compared to age matched controls: a 17-year experience. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:587–596. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0428-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallot V, Berwanger da Silva AL, Genro V, Grynberg M, Frydman N, Fanchin R. Antral follicle responsiveness to follicle-stimulating hormone administration assessed by the Follicular Output RaTe (FORT) may predict in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer outcome. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2012;27:1066–1072. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genro VK, Grynberg M, Scheffer JB, Roux I, Frydman R, Fanchin R. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels are negatively related to Follicular Output RaTe (FORT) in normo-cycling women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2011;26:671–677. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cakmak H, Katz A, Cedars MI, Rosen MP. Effective method for emergency fertility preservation: random-start controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobo A, Garcia-Velasco JA, Domingo J, Remohí J, Pellicer AI. vitrification of oocytes useful for fertility preservation for age-related fertility decline and in cancer patients? Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1485–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal L, Leykin L, Schifren JL, Isaacson KB, Chang YC, Nikruil N, et al. Malignancy may adversely influence the quality and behaviour of oocytes. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 1998;13:1837–1840. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.7.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quintero RB, Helmer A, Huang JQ, Westphal LM. Ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation in patients with cancer. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:865–868. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klock SC, Zhang JX, Kazer RR. Fertility preservation for female cancer patients: early clinical experience. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almog B, Azem F, Gordon D, Pauzner D, Amit A, Barkan G, et al. Effects of cancer on ovarian response in controlled ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:957–960. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das M, Shehata F, Moria A, Holzer H, Son W-Y, Tulandi T. Ovarian reserve, response to gonadotropins, and oocyte maturity in women with malignancy. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devesa M, Martínez F, Coroleu B, Rodríguez I, González C, Barri PN. Ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women with cancer is as expected according to an age-specific nomogram. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:583–588. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopman JM, Noyes N, Talebian S, Krey LC, Grifo JA, Licciardi F. Women with cancer undergoing ART for fertility preservation: a cohort study of their response to exogenous gonadotropins. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1476–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin I, Almog B. Effect of cancer on ovarian function in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization for fertility preservation: a reappraisal. Curr Oncol Tor Ont. 2013;20:e1–e3. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michaan N, Ben-David G, Ben-Yosef D, Almog B, Many A, Pauzner D, et al. Ovarian stimulation and emergency in vitro fertilization for fertility preservation in cancer patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149:175–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn MM, Cakmak H, Letourneau JM, Cedars MI, Rosen MP. Response to ovarian stimulation is not impacted by a breast cancer diagnosis. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2017;32:568–74 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Robertson AD, Missmer SA, Ginsburg ES. Embryo yield after in vitro fertilization in women undergoing embryo banking for fertility preservation before chemotherapy. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:588–591. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulandi T, Holzer H. Effects of malignancies on the gonadal function. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:813–815. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Druckenmiller S, Goldman KN, Labella PA, Fino ME, Bazzocchi A, Noyes N. Successful oocyte cryopreservation in reproductive-aged cancer survivors. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:474–480. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavone ME, Hirshfeld-Cytron J, Lawson AK, Smith K, Kazer R, Klock S. Fertility preservation outcomes may differ by cancer diagnosis. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2014;7:111–118. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.138869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrenz B, Fehm T, von Wolff M, Soekler M, Huebner S, Henes J, et al. Reduced pretreatment ovarian reserve in premenopausal female patients with Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin-lymphoma—evaluation by using antimüllerian hormone and retrieved oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamdine O, Eijkemans MJC, Lentjes EWG, Torrance HL, Macklon NS, Fauser BCJM, et al. Ovarian response prediction in GnRH antagonist treatment for IVF using anti-Müllerian hormone. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2015;30:170–178. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iliodromiti S, Nelson SM. Ovarian response biomarkers: physiology and performance. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:182–186. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang N, Hao C-F, Zhuang L-L, Liu X-Y, HF G, Liu S, et al. Prediction of IVF/ICSI outcome based on the follicular output rate. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shima K, Kitayama S, Nakano R. Gonadotropin binding sites in human ovarian follicles and corpora lutea during the menstrual cycle. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gougeon A. Regulation of ovarian follicular development in primates: facts and hypotheses. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:121–155. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-2-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura K, Sheps S, Arck PC. Stress and reproductive failure: past notions, present insights and future directions. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25:47–62. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schenker JG, Meirow D, Schenker E. Stress and human reproduction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;45:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanchin R, Schonäuer LM, Cunha-Filho JS, Méndez Lozano DH, Frydman R. Coordination of antral follicle growth: basis for innovative concepts of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Semin Reprod Med. 2005;23:354–362. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-923393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cakmak H, Rosen MP. Random-start ovarian stimulation in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27:215–221. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]