Abstract

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of gender on operative rates and outcomes in men and women with severe aortic stenosis. The institutional echocardiography database was used to identify all adult patients with severe aortic stenosis in the years 2004–2005. Only patients with a class I indication for aortic valve replacement (AVR) during the period of follow up were included in the study. 362 patients were identified with severe aortic stenosis and a class I indication for AVR (52% women). The overall operative rate for the cohort was 72%. In patients who underwent AVR, Kaplan-Meier survival rates were the same for men and women. 64% of women versus 81% of men underwent AVR (P < 0.001). After adjusting for multiple covariates, women had a 2.1-fold reduced odds of undergoing AVR compared to men (P = 0.02). After matching for age and Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) risk score, women underwent AVR at a 19% lower relative rate compared to men (P = 0.03) When stratified by gender, there was no difference in reasons for not undergoing AVR, including rates of declining surgery. In conclusion, despite similar outcomes following surgery, women with severe aortic stenosis are less likely than men to undergo AVR.

Keywords: Aortic Valve Replacement, Gender, Aortic Stenosis

Introduction

The effect of gender on treatment and outcomes in valvular heart disease has not been well studied. Bach and colleagues queried a database of 5 million privately insured and a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries for patients with aortic valve disease and found that women were seen by specialists, underwent diagnostic tests, and underwent AVR at rates significantly lower than men1. However, severity of valve disease in relation to diagnosis and treatment could not be assessed. Guidelines support AVR for patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are symptomatic, asymptomatic and undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery, or who have an ejection fraction < 50%2.

The purpose of our study was twofold: 1) to assess operative rates and outcomes stratified by gender and operative risk in patients with severe AS and a class I indication for AVR and 2) to evaluate why medically managed patients in this cohort did not undergo AVR.

Methods

This study was approved by our institution’s internal review board. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need for patient consent was waived. The Massachusetts General Hospital echocardiography database was used to identify all adult patients with severe AS in the years 2004 and 2005. Severe AS was defined as a mean gradient > 40 mmHg and an aortic valve area < 1 cm2. 467 patients were identified and comprehensive chart review was performed. A total of 55 patients (30 male, 25 female) were excluded because of incomplete medical records (47 patients), the presence of prosthetic valve AS (4 patients), and the inability to determine whether the patient was alive or dead with the social security death index because they were traveling from a different country (4 patients). Of the remaining 412 patients, 368 patients were identified as having a class I indication for AVR during the period of follow up. Six patients (3 women, 3 men) were excluded because of moderate to severe mitral stenosis (mean trans-mitral gradient ≥ 5 mmHg), leaving 362 patients for subsequent analysis. Baseline characteristics including time of initial diagnosis of severe AS, symptoms, co-morbidities, and echocardiographic data were collected. The follow-up period was defined as the date of development of a class I indication for AVR to the date that the social security death index was queried for each patient. If the patient was not operated on during the period of follow up, the reason for no operation was assessed and assigned to one of 4 categories based on documentation in the medical record: advanced age (if age was documented as the major reason for the patient or the treating physician), co-morbidities other than advanced age, patient declined, or other.

Clinical variables were assessed at the time the patient developed a class I indication for AVR at our institution. A history of chest pain, dyspnea on exertion, and syncope were identified via medical records. Patients were considered asymptomatic if none of these symptoms were elicited in the history. Heart failure severity was assigned based on the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class index. Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure greater than 140/90 mmHg or need for antihypertensive medication. Chronic renal insufficiency was defined as a creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting blood glucose > 125 mg/dL or the need for antidiabetic agents. A prior myocardial infarction was defined as a history of a biomarker positive infarction or evidence of scar on echocardiography. Coronary artery disease was defined as a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention, or > 70% lesion (> 50% for a lesion in the left main). Lung disease was considered present if the patient required daily inhalers. Peripheral vascular disease was defined as carotid stenosis > 70% or requiring surgery, presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, a history of peripheral vascular bypass surgery or stenting, or a history of significant claudication. A patient was identified as having cancer if the cancer was actively being treated at the time of diagnosis of severe AS or at any time during the follow-up period. Data were collected from two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiographic examinations or transesophageal echocardiography. Peak and mean transaortic gradients were identified from continuous wave Doppler measurements in at least two views. The aortic valve area (AVA) was calculated using the continuity equation. Aortic valve area index was calculated as the AVA/body surface area. Relative wall thickness was defined as (2 × posterior wall thickness)/left ventricular end diastolic diameter.

Operative mortality risk for AVR was assessed by the online STS score calculator3 due to its enhanced accuracy in assessing risk of AVR compared to the EuroScore4. Patients requiring double valve surgery or ascending aortic operation (n=31, 22 men and 9 women) were excluded from analyses utilizing the STS score as it does not support accurate mortality estimates in more complex surgeries. The endpoints of the study were performance of AVR and all cause mortality. All cause mortality was determined by querying the social security death index5.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 8.0 and graphics were created with GraphPad Prism 5.0. Normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). Group baseline characteristics were compared with the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U statistic for continuous variables, or Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess the probability of undergoing AVR. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier product-limit analysis with log-rank comparison testing and multivariate Cox regression models. Multivariate analyses were performed by incorporating variables from univariate analysis that achieved a p-value ≤0.05 and utilizing a stepwise backward elimination protocol. A matching analysis was performed between women and men using the nearest neighbor approach and requiring an age difference ≤1 year and an STS score difference ≤3%. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

We identified 362 patients with severe AS and a Class I indication for AVR, of which 52% were female. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Women were older than men and were less likely to have coronary disease or to have undergone coronary revascularization (Table 1). Women had a higher LVEF and relative wall thickness at the time of diagnosis indicating a greater relative degree of hypertrophy compared to men. There was no significant difference in the percentage of women versus men with a LVEF < 50%. Transaortic gradients, aortic valve area index, degree of mitral regurgitation, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure were not significantly different between men and women.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Female (190) | Male (172) | P -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 78 ± 10 | 72 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Body Surface Area (m2) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms: | |||

| Asymptomatic | 7% (14) | 6% (10) | 0.55 |

| Chest Pain | 23% (44) | 35% (61) | 0.01 |

| Dyspnea on Exertion | 79% (151) | 78% (135) | 0.82 |

| Syncope | 13% (25) | 9% (16) | 0.25 |

| New York Heart Association: | |||

| Class I | 45% (85) | 50% (86) | 0.32 |

| Class II | 34% (65) | 35% (60) | 0.89 |

| Class III | 16% (30) | 12% (20) | 0.25 |

| Class IV | 5% (10) | 3% (6) | 0.41 |

| Shock | 2% (4) | 2% (3) | 0.80 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 34% (64) | 52% (90) | <0.001 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 13% (24) | 19% (33) | 0.09 |

| Prior Percutaneous Intervention | 8% (15) | 16% (27) | 0.02 |

| Prior Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | 2% (4) | 14% (24) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20% (38) | 23% (39) | 0.54 |

| Hypertension | 85% (161) | 88% (151) | 0.40 |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency | 17% (32) | 20% (35) | 0.39 |

| Lung disease | 16% (31) | 16% (27) | 0.87 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 8% (16) | 14% (24) | 0.10 |

| Cancer | 5% (9) | 6% (11) | 0.49 |

Measurements are presented as mean ± SD or percentage of total (n).

Table 2.

Baseline Echocardiographic Characteristics

| Female (190) | Male (172) | P -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 69 (60–75) | 62 (54–70) | <0.001 |

| Ejection Fraction < 50% | 11% (21) | 17% (30) | 0.08 |

| Ejection Fraction ≤ 35% | 4% (7) | 6% (11) | 0.24 |

| Left Ventricular Outflow Tract (cm) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| End Diastolic Dimension (mm) | 42 ± 5 | 49 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Posterior Wall Thickness (mm) | 11.9 ± 2.0 | 12.4 ± 2.0 | 0.02 |

| Septal Wall Thickness (mm) | 12.7 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 0.09 |

| Relative Wall Thickness | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 0.52 ± 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Aortic Valve Area (cm2) | 0.62 ± 0.15 | 0.70 ± 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Aortic Valve Area index | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.26 |

| Aortic Valve Peak Gradient (mmHg) | 91 ± 24 | 88 ± 22 | 0.28 |

| Aortic Valve Mean Gradient (mmHg) | 56 ± 15 | 54 ± 13 | 0.22 |

| Mitral Regurgitation Grade 3 or 4 | 15% (29) | 10% (18) | 0.18 |

| Aortic Insufficiency Grade 3 or 4 | 6% (11) | 6% (11) | 0.81 |

| Bicuspid Aortic Valve | 8% (15) | 16% (28) | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure (mmHg) | 47 ± 14 | 45 ± 14 | 0.31 |

Measurements are presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range) or percentage of total (n).

The operative rate for the entire cohort was 72% (261/362). The mean period of follow up for the cohort (n=362) was 4.2 years. Among women, the indications for AVR included (many patients had multiple indications): abnormal LVEF < fifty percent 11% (21/190), angina 23% (44/190), dyspnea on exertion 79% (151/190), syncope 13% (25/190), and symptoms of congestive heart failure 55% (105/190). Among men, the indications for AVR included: LVEF < fifty percent 17% (30/172), angina 35% (61/172), dyspnea on exertion 78% (135/172), syncope 9% (16/172), symptoms of congestive heart failure 50% (86/172), and asymptomatic but undergoing ascending aortic surgery for aortic aneurysm 2% (4/172, all 4 had bicuspid aortic valves). Compared to women, men were more likely to have angina (P = 0.01) and concomitant cardiac surgery for aortic aneurysm (P = 0.05, Fisher’s exact test) as an indication for AVR.

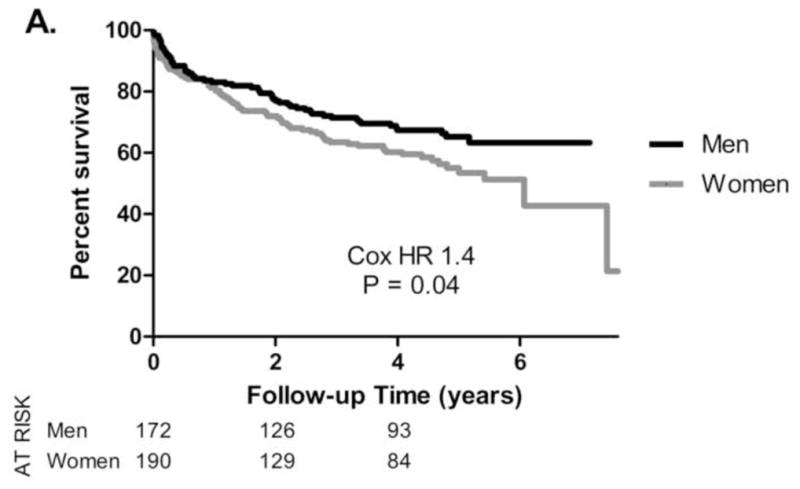

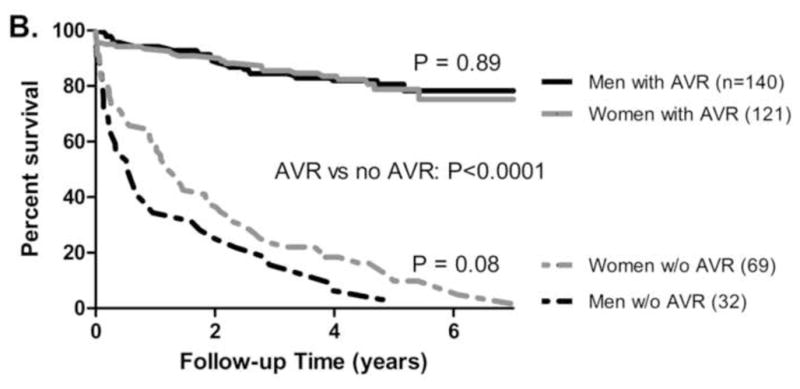

Overall, women had decreased survival compared to men (Cox hazard ratio 1.4, P = 0.04, Figure 1A). As expected, patients who underwent AVR had improved survival (Figure 1B, P < 0.0001). In patients who underwent AVR, mortality outcomes were similar for men and women (Figure 1B). 64% (121/190) of women versus 81% (140/172) of men underwent AVR (Pearson’s χ2, P < 0.001). Given that women were older than men at baseline, a regression analysis stratified by age was performed. Three age ranges were defined (< 65, 65–80, >80 years) and operative rates within each group were compared for women and men. Multivariate regression analysis for the entire cohort identified gender as a significant predictor of undergoing AVR, with a 2.0-fold reduced odds for women undergoing operation (P = 0.01), after adjusting for the three age groups (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Survival stratified by Gender and Operative Status.

Kaplan-Meier survival in 362 patients with severe aortic stenosis and a Class I indication for AVR, stratified by gender (A) or by gender and operative status (B). Women exhibited increased mortality (Cox hazard ratio 1.4, P = 0.04, 1A). Survival was significantly improved in patients undergoing AVR (P < 0.0001, 1B). Survival outcomes were similar for men and women who underwent AVR (P= 0.89).

Figure 2. Operative Rates stratified by Gender and Age.

Operative rates in 362 patients with severe aortic stenosis and a Class I indication for AVR. Comparison of operative rates in women and men for each individual age group (<65, 65–80, >80 years) was performed using Pearson’s χ2 analysis. Multivariate logistic regression for the entire cohort identified gender as a significant predictor of undergoing AVR, with a 2.0-fold reduced odds for women undergoing operation (P = 0.01), after adjusting for the three age groups above.

Predictors of all-cause mortality are included in Table 3. In addition to expected variables, relative wall thickness was an independent predictor of increased mortality. Women had a greater relative wall thickness compared to men (0.58 ± 0.13 versus 0.52 ± 0.11, P < 0.001), indicating a greater relative degree of hypertrophy in women. For every 10% increment in relative wall thickness, the adjusted Cox regression mortality hazard ratio was 1.29 (95% CI 1.12–1.50, P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Predictors of All-Cause Mortality

| Variable | Cox Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (for every decade) | 1.42 (1.13–1.78) | 0.002 |

| New York Heart Association Class (for every class increase) | 1.37 (1.10–1.70) | 0.005 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 2.13 (1.32–3.44) | 0.002 |

| Lung Disease | 2.41 (1.52–3.83) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (every 1.0 mg/dL increase) | 1.21 (1.05–1.39) | 0.008 |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (every 5% increase) | 0.89 (0.83–0.96) | 0.002 |

| Relative Wall Thickness (every 10% increase) | 1.29 (1.12–1.50) | 0.001 |

| Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement | 0.14 (0.09–0.22) | <0.001 |

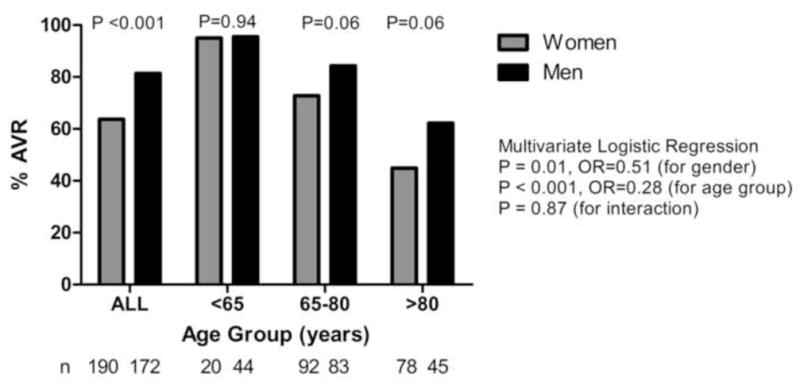

We found that 83% (143/172) of men with a Class I indication for AVR were referred for evaluation by a cardiac surgeon versus 68% (130/190) of women (Pearson’s χ2, P = 0.001). Of those referred for cardiac surgical evaluation, 98% (140/143) of the men underwent AVR versus 93% (121/130) of the women (P = 0.07). Independent predictors of undergoing AVR are shown in Table 4. Age, NYHA class, and the presence of chest pain were significant predictors of undergoing AVR. However, even after adjusting for these and other variables, gender remained an independent predictor of undergoing AVR, with men having a 2.1-fold increased odds of being operated on compared to women (P = 0.02, Table 4). When STS scores were added to the logistic regression model (odds ratio 0.90 for every 1% increase in score, P=0.026), age was no longer a significant predictor of AVR. However, gender remained an independent predictor with men having a 2.7-fold increased odds of operation (P=0.001). Stratification of patients by STS score and gender revealed that the majority of the patients had an operative mortality estimated at less than 5% (Figure 3). In this cohort of patients with the lowest risk, women were 12% less likely than men to undergo AVR (Figure 3, P = 0.04).

Table 4.

Independent Predictors of Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) | <0.001 |

| Chest Pain | 2.34 (1.11–4.94) | 0.03 |

| New York Heart Association Class (every class decrease) | 1.66 (1.21–2.28) | 0.002 |

| Absence of Prior Myocardial Infarction | 2.85 (1.31–6.19) | 0.008 |

| Absence of Chronic Renal Insufficiency | 2.48 (1.25–4.90) | 0.010 |

| Absence of Cancer | 7.88 (2.35–26.5) | 0.001 |

| Aortic Valve Mean Gradient (every 10 mmHg increase) | 1.34 (1.05–1.71) | 0.018 |

| Male Gender | 2.08 (1.13–3.81) | 0.018 |

Figure 3. Operative Rates Stratified by Operative Risk.

Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) operative risk scores were assessed for each patient. Operative risk was stratified into three groups (mortality < 5%, 5–10%, > 10%). Comparison of operative rates in women and men for each risk group was performed using Pearson’s χ2 analysis, with a significant difference observed in those with STS scores <5%. A multivariate logistic regression model revealed a 1.9-fold reduced odds for women undergoing operation (P = 0.01) after adjusting for the three risk groups above.

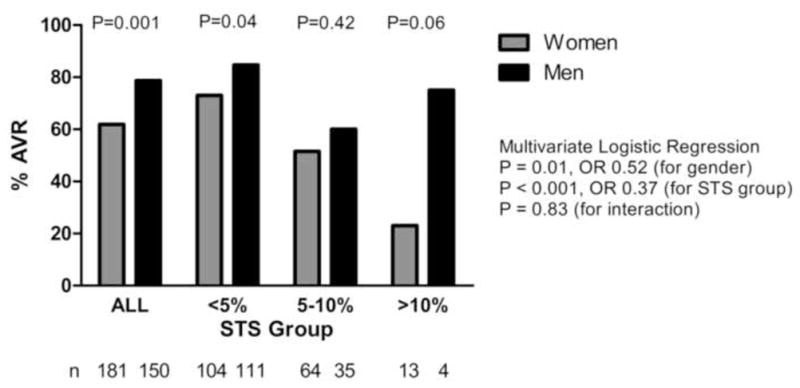

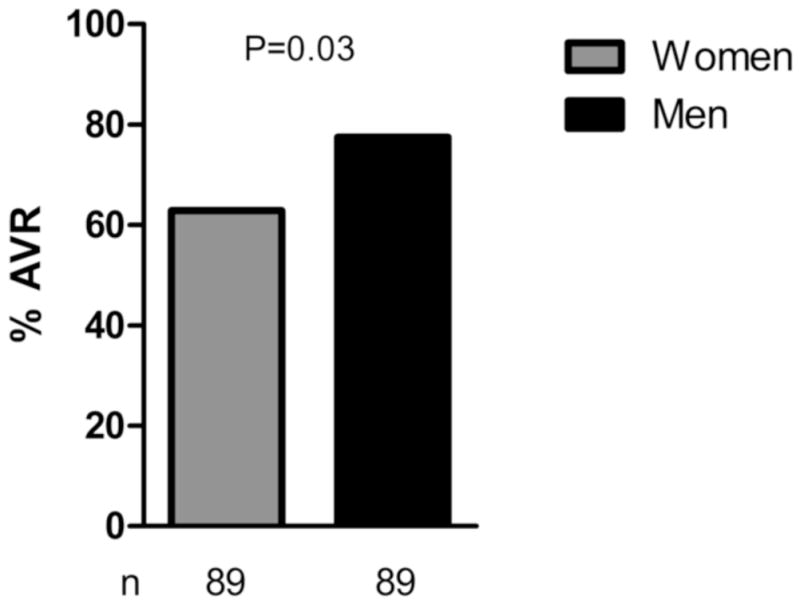

A nearest neighbor matching analysis was performed for men and women based on age (requiring ≤1 year difference) and STS score (≤3% difference) resulting in 89 matched pairs identified. Table 5 reveals the baseline characteristics of the matched men and women. In this cohort of matched patients, women were once again less likely to undergo AVR with a 19% relative reduction in operative rates compared to men (Figure 4, P = 0.03).

Table 5.

Baseline Characteristics of 89 Gender Matched Pairs

| Female (89) | Male (89) | P -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.2 ± 8.9 | 75.3 ± 8.9 | 0.96 |

| STS Score | 3.5 (2.3–5.0) Range 0.7–8.9 |

3.0 (2.0–4.6) Range 0.5–9.2 |

0.15 |

| Symptoms: | |||

| Chest Pain | 18% (16) | 30% (27) | 0.04 |

| Dyspnea on Exertion | 76% (68) | 72% (64) | 0.42 |

| Syncope | 9% (8) | 9% (8) | 1.0 |

| New York Heart Association: | |||

| Class I | 43% (38) | 44% (39) | 0.88 |

| Class II | 27% (24) | 32% (28) | 0.43 |

| Class III | 15% (13) | 10% (9) | 0.28 |

| Class IV | 4% (4) | 3% (3) | 0.70 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 28% (25) | 44% (39) | 0.02 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 10% (9) | 15% (13) | 0.28 |

| Prior CABG | 3% (3) | 8% (7) | 0.21 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20% (18) | 22% (20) | 0.72 |

| Hypertension | 78% (69) | 79% (70) | 0.82 |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency | 13% (12) | 14% (12) | 0.83 |

| Lung disease | 16% (14) | 13% (12) | 0.54 |

| Cancer | 6% (5) | 6% (5) | 1.0 |

| AV Mean Gradient (mmHg) | 55±15 | 53±13 | 0.25 |

| LVEF ≤ 50% | 9% (8) | 10% (9) | 0.81 |

| Bicuspid Valve | 7% (6) | 6% (5) | 0.77 |

Figure 4. Operative Rates in Men and Women Matched by Age and STS Score.

Men and women within 1 yr of age and 3% STS score were matched and operative rates were assessed. 63% of women versus 78% of men underwent operation in this matched cohort (P = 0.03).

In patients undergoing AVR, men and women underwent concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting, mitral valve repair or replacement, and tricuspid valve annuloplasty at similar rates (Table 6). Men were more likely to undergo ascending aortic operations while women had a higher rate of myomectomy (Table 6). In the cohort of patients who did not undergo AVR, the most common reason cited for no AVR was the presence of co-morbidities (Table 7). The category “other” was assigned to 4 women and 2 men. Among the women, 3 had no clear reason in the medical chart for not undergoing AVR and 1 died of sepsis prior to the planned operation. 1 man died of a cardiac arrest prior to his planned operation and 1 man had discrepant transaortic gradient findings at cardiac catheterization. There was a trend for co-morbidities other than advanced age being a more common reason for not operating in men compared to women (P=0.06). There was no significant difference in the rates of declining surgery.

Table 6.

Concomitant Surgeries

| Female (121) | Male (140) | P -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | 40% (49) | 43% (60) | 0.70 |

| Ascending Aorta Operation | 3% (4) | 11% (16) | 0.01 |

| Mitral Valve Repair or Replacement | 1% (1) | 2% (3) | 0.63 |

| Tricuspid Valve Annuloplasty | 3% (4) | 1% (2) | 0.42 |

| Septal Myomectomy | 14% (17) | 5% (7) | 0.01 |

Table 7.

Reason for No Aortic Valve Replacement

| Female (69) | Male (33) | P -Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 12% (8) | 3% (1) | 0.27 |

| Co-morbidities | 46% (32) | 67% (22) | 0.06 |

| Declined | 36% (25) | 24% (8) | 0.26 |

| Other | 6% (4) | 6% (2) | 1.0 |

Discussion

Multiple studies have documented gender disparities in the treatment of ischemic heart disease6–14, but to our knowledge only one study has directly investigated gender disparities in the treatment of valvular heart disease1. Building on earlier work performed by Bach and colleagues1, we confirm a difference in referrals to cardiac surgeons and operative rates in men versus women with severe AS and a class I indication for undergoing AVR. Interpretation of this difference is complicated by differences in baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1 and 2). At baseline, women were older than men, had a higher LVEF, and less coronary disease. The decision to operate, particularly in older patients, requires carefully weighing the morbidity and mortality of open heart surgery against the dismal prognosis of untreated symptomatic severe AS. We addressed the differences in Table 1 in three types of analyses: multivariate logistic regression to identify independent predictors of undergoing AVR, stratification based on age and STS score, and a matching analysis. All analyses revealed lower operative rates in women compared to men.

Most published reports looking at gender disparity in the treatment of ischemic heart disease have consistently shown that women are treated with less invasive management strategies6–14, a finding in line with our own study. The reasons for this discrepancy are difficult to decipher. In the investigation of why patients did not undergo AVR, there was no significant difference in rates of declining operations (Table 7). Men had higher rates of coronary disease (Table 1) and were more likely to have chest pain as an indication for AVR. It is possible that anginal symptoms lowered the threshold for referral in men as opposed to women, although ultimately both genders underwent CABG at similar rates (Table 6). Even after adjusting for the presence of angina and prior myocardial infarction, gender was an independent predictor of undergoing operation (Table 4). In interpreting Table 4 it is important to note that this cohort of patients all had a class I indication for AVR; thus it is not surprising that AVA was not an independent predictor of undergoing surgery.

Men had a higher incidence of bicuspid aortic valve morphology, which is consistent with previous studies documenting increased incidence of bicuspid aortic valves among males in asymptomatic neonates screened for valve morphology15 and adults presenting for AVR16. Bicuspid aortic valves are known to be associated with an increased incidence of aortic aneurysms17 which provides an explanation for why men were more likely than women to undergo ascending aortic operations in conjunction with AVR (Table 6).

We found that women had a higher relative wall thickness compared to men, which may explain why women were more likely to undergo a myomectomy (Table 6). The presence of a greater degree of relative hypertrophy preoperatively in our cohort is consistent with literature suggesting that gender impacts the development of hypertrophy in AS18–19. Interestingly, we found higher relative wall thickness was associated with an increased risk of mortality. There is a mounting body of evidence that AVR may be beneficial in some patients with AS who are asymptomatic20. The measurement of relative wall thickness may have implications for surgical referral in patients who are minimally symptomatic with severe AS.

Despite being older, we found that women who underwent AVR had similar outcomes compared to men. This is consistent with a recent investigation by Fuchs, et al in which survival outcomes after AVR in women versus men with isolated severe AS were similar21. They also reported that in the quintile of patients > 79 years, women had significantly better survival outcomes compared to men after AVR21. The feasibility and benefit of AVR in elderly patients has been documented previously22–23. This is important given we found the greatest disparity in operative rates in patients > 80 years (Figure 2).

Our data regarding referral patterns revealed that 83% of men and 68% of women were referred for evaluation by a cardiac surgeon. Both genders had operative rates > 90% once evaluated by a cardiac surgeon, suggesting that operative candidates were preselected by referring physicians. This is consistent with a previous study in which only 30% of medically managed patients with severe AS were evaluated by a cardiac surgeon24. It is possible that patients and referring physicians are overestimating the risk of surgery in elderly women, suggesting that a multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons and referring physicians in decision making would be beneficial.

Investigating gender bias in the treatment of cardiovascular disease is challenging. Randomized controlled trials are designed to eliminate bias. Prospective studies may heighten awareness of physicians and patients and make identification of gender bias more difficult. Our study is an observational study which increases the likelihood of reflecting true practice patterns. Limitations include the single center nature of the study and the inability to assess the cause of death (including cardiac versus non-cardiac) in the majority of patients. Given our findings, further investigation into treatment disparities in women with severe valvular disease is warranted.

Footnotes

The authors have no relationships with industry to disclose.

References

- 1.Bach DS, Radeva JI, Birnbaum HG, Fournier AA, Tuttle EG. Prevalence, referral patterns, testing, and surgery in aortic valve disease: leaving women and elderly patients behind? J Heart Valve Dis. 2007;16:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O’Gara PT, O’Rourke RA, Otto CM, Shah PM, Shanewise JS. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e1–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.http://209.220.160.181/STSWebRiskCalc261/de.aspx

- 4.Wendt D, Osswald BR, Kayser K, Thielmann M, Tossios P, Massoudy P, Kamler M, Jakob H. Society of Thoracic Surgeons score is superior to the EuroSCORE determining mortality in high risk patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.http://ssdi.rootsweb.ancestry.com

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steingart RM, Packer M, Hamm P, Coglianese ME, Gersh B, Geltman EM, Sollano J, Katz S, Moye L, Basta LL, Lewis SJ, Gottlieb SS, Bernstein V, McEwan P, Jacobson K, Brown EJ, Kukin ML, Kantrowitz NE, Pfeffer MA the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. Sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:226–230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV, Manhapra A, Mallik S, Krumholz HM. Sex and racial differences in the management of acute myocardial infarction, 1994 through 2002. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:671–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa032214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roger VL, Farkouh ME, Weston SA, Reeder GS, Jacobsen SJ, Zinsmeister AR, Yawn BP, Kopecky SL, Gabriel SE. Sex differences in evaluation and outcome of unstable angina. Jama. 2000;283:646–652. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.5.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hvelplund A, Galatius S, Madsen M, Rasmussen JN, Rasmussen S, Madsen JK, Sand NP, Tilsted HH, Thayssen P, Sindby E, Hojbjerg S, Abildstrom SZ. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:684–690. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, Brieger D, Gurfinkel EP, Steg PG, Fitzgerald G, Jackson EA, Eagle KA. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart. 2009;95:20–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.138537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nante N, Messina G, Cecchini M, Bertetto O, Moirano F, McKee M. Sex differences in use of interventional cardiology persist after risk adjustment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:203–208. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle F, De La Harpe D, McGee H, Shelley E, Conroy R. Gender differences in the presentation and management of acute coronary syndromes: a national sample of 1365 admissions. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:376–379. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000160725.82293.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen JT, Berger AK, Duval S, Luepker RV. Gender disparity in cardiac procedures and medication use for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tutar E, Ekici F, Atalay S, Nacar N. The prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in newborns by echocardiographic screening. Am Heart J. 2005;150:513–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts WC, Ko JM. Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid, and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005;111:920–925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155623.48408.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer M, Bauer U, Siniawski H, Hetzer R. Differences in clinical manifestations in patients with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valves undergoing surgery of the aortic valve and/or ascending aorta. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:485–490. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrov G, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Krabatsch T, Dunkel A, Dandel M, Dworatzek E, Mahmoodzadeh S, Schubert C, Becher E, Hampl H, Hetzer R. Regression of myocardial hypertrophy after aortic valve replacement: faster in women? Circulation. 2010;122:S23–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villari B, Campbell SE, Schneider J, Vassalli G, Chiariello M, Hess OM. Sex-dependent differences in left ventricular function and structure in chronic pressure overload. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:1410–1419. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown ML, Pellikka PA, Schaff HV, Scott CG, Mullany CJ, Sundt TM, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Orszulak TA. The benefits of early valve replacement in asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs C, Mascherbauer J, Rosenhek R, Pernicka E, Klaar U, Scholten C, Heger M, Wollenek G, Czerny M, Maurer G, Baumgartner H. Gender differences in clinical presentation and surgical outcome of aortic stenosis. Heart. 2010;96:539–545. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.186650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Survival in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis is dramatically improved by aortic valve replacement: Results from a cohort of 277 patients aged ≥ 80 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unic D, Leacche M, Paul S, Rawn JD, Aranki SF, Couper GS, Mihaljevic T, Rizzo RJ, Cohn LH, O’Gara PT, Byrne JG. Early and late results of isolated andcombined heart valve surgery in patients ≥ 80 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1500–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bach DS, Siao D, Girard SE, Duvernoy C, McCallister BD, Jr, Gualano SK. Evaluation of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who do not undergo aortic valve replacement: the potential role of subjectively overestimated operative risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:533–539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.848259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]