Abstract

Background:

Being homeless or vulnerably housed is associated with death at a young age, frequently related to medical problems complicated by drug or alcohol dependence. Homeless people experience high symptom burden at the end of life, yet palliative care service use is limited.

Aim:

To explore the views and experiences of current and formerly homeless people, frontline homelessness staff (from hostels, day centres and outreach teams) and health- and social-care providers, regarding challenges to supporting homeless people with advanced ill health, and to make suggestions for improving care.

Design:

Thematic analysis of data collected using focus groups and interviews.

Participants:

Single homeless people (n = 28), formerly homeless people (n = 10), health- and social-care providers (n = 48), hostel staff (n = 30) and outreach staff (n = 10).

Results:

This research documents growing concern that many homeless people are dying in unsupported, unacceptable situations. It highlights the complexities of identifying who is palliative and lack of appropriate places of care for people who are homeless with high support needs, particularly in combination with substance misuse issues.

Conclusion:

Due to the lack of alternatives, homeless people with advanced ill health often remain in hostels. Conflict between the recovery-focused nature of many services and the realities of health and illness for often young homeless people result in a lack of person-centred care. Greater multidisciplinary working, extended in-reach into hostels from health and social services and training for all professional groups along with more access to appropriate supported accommodation are required to improve care for homeless people with advanced ill health.

Keywords: Homeless persons, Personality disorders, end-of-life care, qualitative, substance-related disorders, palliative care

What is already known about the topic?

People who are homeless are often poorly engaged with the healthcare system, their health is often bad and death occurs at a young age.

Many homeless people experience tri-morbidity, a combination of physical and mental health problems and substance misuse.

Barriers to healthcare access for this group include perceived discrimination, zero-tolerance policies of facilities, unstable housing situations and inflexibility in existing services.

What this paper adds?

An insight into the lack of support and choices that many homeless people with advanced ill health receive.

Due to the lack of alternatives, homeless people with advanced ill health often remain in hostels as their health deteriorates.

Uncertainty around the prognoses of common illnesses, the impact of behaviours related to complex trauma and substance misuse and gaps and fragmentation in existing provision contribute to the difficulty in accessing and providing palliative care for this population.

Conflict between the recovery-focused nature of many services and the realities of health and illness for homeless people result in a lack of person-centred care for those with advanced ill health.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

If hostels are to continue to house people with chronic, deteriorating health conditions, far greater multidisciplinary in-reach, support and training are required.

Given that identifying which individuals may be approaching the end of their life is difficult, the trigger for action and support to be put in place could be when an individual’s health is causing concern, rather than when they are identified as dying.

A bespoke service, providing an appropriate level of care and support for homeless people who are dying, in an environment in which they can feel comfortable may be required.

Background

Homeless people encounter barriers in accessing healthcare services, experience poor health outcomes and early mortality.1,2 The mean age of death among single homeless people ranges from 34 to 47 years, with age-adjusted death rates up to four times the housed population.1,3,4 ‘Homelessness’ includes people sleeping on the streets (rough sleeping) and in insecure or temporary accommodation, including hostels.2 In 2016, on any given night, it was estimated that approximately 4134 people were sleeping on the streets (sleeping rough) across England. This figure is likely to be an underestimation and represents a 16% rise in the numbers observed in 2015 and more than double the amount in 2010.5

Homeless people’s health needs frequently include drug and/or alcohol dependence and mental health problems in association with physical health issues (tri-morbidity).6,7 A recent survey of healthcare usage of UK homeless people indicated many homeless people under-utilise primary care services while emergency health service usage is high.6,8 This appears to be a pattern internationally.9

Challenges to accessing healthcare include navigating complicated healthcare systems,10 managing unstable housing situations, balancing competing priorities (such as food, shelter and addictions)11 and previous negative experiences with healthcare services and professionals.12

Poorly managed addictions can make accessing healthcare within mainstream settings challenging due to fear of discrimination11 or medication delays leading to unpleasant symptoms of withdrawal.11

Policies of zero tolerance towards illicit substances (such as crack and heroin) are common in many services, including care homes and hospital. Sobriety is often a requirement for engaging in health- and social-care assessments.12,13 In practical terms, these factors render many services inaccessible to this population.

The deaths of many homeless people are not planned for and occur following emergency admission to hospitals. Despite the high burden of disease and mortality in the homeless population,15 they have poor access to palliative care.16,17 Reasons for this may include the lack of positive interactions between homeless people and healthcare providers,18 challenges around alcohol and substance use17 and methods and models of service delivery.19,20 Homeless people are less likely to have family members to advocate for them should their health deteriorate, thus the potential importance of advance care planning (ACP) for this group has been raised.21 ACP is a process of discussion about future healthcare wishes, usually in the context of anticipated health deterioration.22 ACP is a central aspect of palliative care yet rarely occurs with homeless people.17 Research indicates that homeless people may be willing to engage in ACP, yet varying degrees of success in engaging homeless people in this have been reported.21,23–26 Given the complexities in providing palliative care for homeless people, there is a need to hear the experiences and views of this group and the professionals supporting them regarding palliative care.

Aims

To explore the views and experiences of current and formerly homeless people, frontline homelessness staff (from hostels, day centres and outreach teams) and health- and social-care providers, regarding challenges to supporting homeless people with advanced ill health, and to make suggestions for improving care.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited using opportunistic sampling across three London boroughs, selected for their high numbers of both homeless people and homelessness services.27,28 Frontline homelessness staff and health- and social-care professionals were recruited through the research team’s existing professional connections and through mapping homelessness services within these boroughs.28

Formerly homeless people were recruited through homelessness charities: Pathway,29 Groundswell30 and St Mungo’s.31 Homeless people were identified and recruited by staff at homeless hostels and day centres.

Homeless hostels provide accommodation and support from key workers, while day centres provide support with basic needs such as food, clothing and washing facilities, but close at night. Current and formerly homeless participants were provided with a £10 supermarket voucher. Eligibility criteria are outlined in Table 1. We followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) guidelines.32

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for participants.

| Frontline homelessness staff and health- and social-care professionals |

| ● Direct professional contact with people who are homeless ● Experience of working within services for homeless people within the three London boroughs included |

| Formerly homeless people |

| ● More than 6 months lived experience of homelessness ● Securely housed for more than 6 months ● Able and willing to articulate experiences and views |

| People who are currently homeless |

| ● Currently homeless or insecurely housed, for longer than 6 months ● Has recourse to public funds and is therefore entitled to medical and social support ● Considered appropriate to be approached by key worker ● Not under influence of drugs or alcohol during participation ● Able and willing to articulate experiences and views. |

Ethical considerations and informed consent

Formerly homeless people and other professionals experienced in supporting homeless people were consulted regarding appropriate recruitment and data collection methodologies. This consultation resulted in amendments to the original recruitment strategy. Formerly homeless people felt it would be most appropriate for hostel and day centre staff to identify and invite potential participants, rather than using posters to advertise the research.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University College London research ethics committee (reference no. 6927/001). Written consent was obtained from formerly homeless participants and staff, and verbal consent was obtained from homeless participants.

Data collection

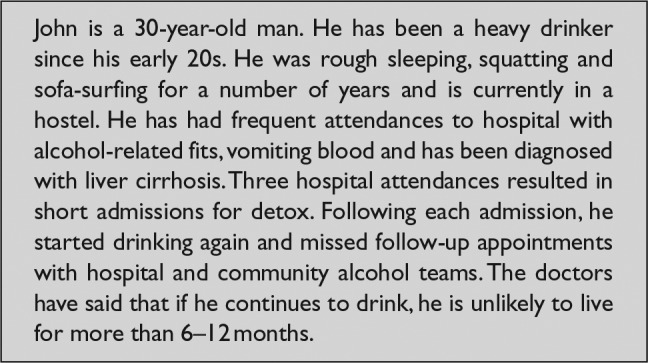

Data were collected between October 2015 and October 2016. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups enabled participants to use their own language and concepts to highlight salient issues.33 Data collection with professionals was conducted at their place of work. Data collection with currently homeless people occurred at the hostels or day centres they were recruited from, while data collection with formerly homeless people took place at the offices of a charity with which all were familiar. A vignette was used (Figure 1) to keep discussions objective.10,34 The vignette provided a familiar scenario and had the potential to stimulate deep exploration of complex problems. Focus groups lasted for 1 h with homeless people, health- and social-care providers and 3 h for all other groups. Participants completed demographic sheets to enable later analysis of the sample. Data collection was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1.

Vignette.

Analysis

Written summaries were circulated to participants to assess accuracy and validity. Thematic analysis35 was used to identify, analyse and report themes from the data. Line-by-line coding was undertaken by B.F.H., and consensus was achieved through discussion (B.F.H. and C.S.). Higher level candidate themes and subthemes (Table 3) were developed and discussed with a wider group of healthcare professionals, researchers and formerly homeless people.

Table 3.

Challenges to the provision and access of palliative care for people who are homeless in London.

| Complex behaviours in mainstream services |

| ● Behaviours related to complex trauma and substance misuse issues; inflexibility and inexperience |

| Gaps in existing systems |

| ● Lack of appropriate alternatives ● Need for holistic approach to care and support ● Hostel as a place of care and death? |

| Uncertainty and complexity |

| ● Difficulty predicting illness trajectories ● Advance care planning |

Results

Participants

A total of 127 participants took part in a total of 28 focus groups and 10 individual semi-structured interviews. Participants’ characteristics are outlined in Table 2. Over one-third (n = 39%) of homeless participants had been homeless for more than 5 years, 86% reported having slept rough (sleeping on the street) and 71% reported currently sleeping in hostels most of the time.

Table 2.

Professional and demographic characteristics of participants.

| Total (N = 127 (%)) | Health/social-care providers (N = 49) | Hostel/outreach staff (N = 40) | Experts by experience (N = 10) | Currently homeless people (N = 28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borough | ||||||

| A | 33 (26) | 9 | 8 | 1 | 6 | |

| B | 36 (28) | 7 | 12 | 4 | 13 | |

| C | 39 (31) | 27 | 12 | – | 9 | |

| Multiple boroughs | 14 (11) | 6 | 8 | – | – | |

| Not reported | 5 (4) | – | – | 5 | – | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 68 (54) | 18 | 16 | 8 | 26 | |

| Female | 59 (46) | 31 | 24 | 2 | 2 | |

| Health- and social-care providers, hostel and outreach staff |

Homeless participants |

|||||

| Total | Health- and social-care providers (N = 49) | Hostel/outreach staff (N= 40) | Experts by experience (N = 10) |

Currently homeless or vulnerably housed people | N = 28 | |

| Place of work | How long have you been homeless? | |||||

| Outreach service | 14 | 12 | – | 2 | Less than 1 year | 4 |

| Hospital | 15 | 14 | – | 1 | 1–4 years | 9 |

| GP surgery | 7 | 7 | – | – | 5–10 years | 6 |

| Hospice | 7 | 7 | – | – | 10–15 years | – |

| Hostel | 31 | 3 | 26 | 2 | 15+ years | 5 |

| Care home | 7 | – | 7 | – | Not reported | 4 |

| Day centre | 5 | – | 5 | – | Have you ever slept rough? | |

| Supported housing | 2 | – | 2 | – | Yes | 24 |

| Council | 6 | 6 | – | – | No | 1 |

| Not reported | 5 | – | – | 5 | Not reported | 3 |

| Job title | How would you describe your health overall? | |||||

| GP | 4 | 4 | – | – | Poor | 8 |

| Nurse practitioner | 7 | 7 | – | – | Fair | 12 |

| Nurse specialist | 11 | 11 | – | – | Good | 4 |

| Drug and alcohol worker | 2 | 2 | – | – | Very good | 1 |

| Addiction psychiatrist | 2 | 2 | – | – | Not reported | 3 |

| Palliative care consultant | 2 | 2 | – | – | Do you use drugs? | |

| Social worker in homelessness or palliative care | 8 | 8 | – | – | Yes | 7 |

| Clinical psychologist | 2 | 2 | – | – | No | 16 |

| Liver specialist | 1 | 1 | – | – | Not reported | 5 |

| Service manager | 1 | 1 | – | – | Do you use methadone/subutex (buprenorphine) | |

| Housing commissioner | 4 | 4 | – | – | Yes | 3 |

| Housing worker | 5 | 3 | – | 2 | No | 20 |

| Hostel worker | 17 | 1 | 16 | – | Not reported | 5 |

| Care navigator | 1 | – | – | 1 | Do you drink alcohol? | |

| Outreach worker | 12 | – | 10 | 2 | Yes | 21 |

| Complex needs hostel worker | 6 | – | 6 | – | No | 2 |

| Hostel manager | 7 | – | 7 | – | Not reported | 5 |

| Day centre manager | 1 | – | 1 | – | Have you been to A&E* in the last year? | |

| Not reported | 6 | 1 | – | 5 | Yes | 15 |

| Years of experience working in homelessness | No | 5 | ||||

| Less than 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | – | Not reported | 8 |

| 1–5 | 17 | 8 | 6 | 3 | Where do you usually sleep? | |

| 5–10 | 27 | 16 | 9 | 2 | Hostel | 20 |

| 10–15 | 23 | 17 | 6 | – | Supported accommodation | 2 |

| 15+ | 14 | 5 | 9 | – | Squat | 2 |

| Not reported | 14 | 1 | 8 | 5 | Friends’ house | 1 |

| Personal experience of homelessness? | ||||||

| Yes | 30 | 8 | 11 | 10 | Street | 1 |

| No | 61 | 41 | 21 | – | Bus | 1 |

| Not reported | 8 | – | 8 | – | Not reported | 1 |

| Experts by experience – how long were you homeless? | ||||||

| 1–5 years | 6 | |||||

| 5–10 years | 2 | |||||

| 10–15 years | 1 | |||||

| Not reported | 1 | |||||

A&E: accident and emergency department of a hospital.

Challenges in the provision of palliative care for homeless people in London

Semi-structured interviews and focus groups identified challenges in providing palliative care to homeless people. Challenges included supporting people with complex trauma and substance misuse in mainstream services, uncertainty around prognosis and complexity associated with homelessness. Gaps and fragmentation in existing systems meant there was often very little choice regarding place of care for homeless people (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Key findings.

| Key findings |

| ● In London, appropriate services for homeless people with advanced ill health are lacking. Facilities that can meet the physical and emotional needs of homeless people with advanced ill health, who may continue to misuse substances, are needed. ● There is currently a large emotional, and practical burden on hostel staff in supporting homeless people with advanced ill health due to lack of appropriate alternatives. Homeless people, and those supporting them, struggle to access the services required. ● There is a conflict between the recovery-focused nature of many services, and the realities of health and illness for homeless people that create a lack of comprehensive person-centred care. ● Collaboration between health, housing and social services, the promotion of multidisciplinary working including hostel in-reach and greater training and support are urgently needed for professionals and those working with homeless people as their health deteriorates. |

Complex behaviours in mainstream health and social services

Behaviours related to complex trauma and substance misuse; inflexibility and inexperience

Health and social services have difficulty supporting the complicated requirements of some homeless people due to their often chaotic lifestyles and addictions. During hospital admissions, it was common for addiction-driven behaviours to cause homeless people to frequently leave the ward to obtain substances or alcohol. This made it difficult for already stretched hospital staff to engage with the person and deliver the care required:

… one problem is that hospitals are so busy … if someone is repeatedly coming back in, full of ascitic fluid, popping off the ward for a couple of cans, they just discharge them … But … if that’s going to be the pattern for the last 6 months of someone’s life, you want to try and actually use it. (General Practitioner – Borough A)

Furthermore, homeless people were avoidant of many mainstream facilities, which seemed alien to them. A preference to remain in the familiar environment of the hostel was described:

There’s been a few guys that were in hospital, told they were dying … they didn’t want to go to any hospice, they didn’t want to … stay in hospital, they wanted to die in the homeless hostel. (Formerly homeless person – Borough B)

The inexperience of many professionals alongside the difficulties of working with people with challenging behaviours in mainstream settings was sometimes translated into a perceived prejudice and lack of compassion towards homeless people:

I think there’s a stigma … and professionals see it as a choice, you choose to pick the can up and put it to your mouth, rather than you being mentally and physically sick … So they just think ‘You’re wasting our time, you didn’t have to pick up that drink’, but there’s so much more behind it than just picking up the drink. (Formerly homeless person – Borough B)

This complexity negatively affected the way that homeless people were able to access services, meaning assessments and the delivery of services were challenged:

Social services say ‘they’re still drinking, so we’re not going to give them a package of care’. Even if they’re drinking, they still need to get in and out of a bath, or use a commode. Their drinking doesn’t mean they’re not entitled to services. (Drug and alcohol worker – Borough B)

Gaps in existing systems

Lack of alternatives

Homeless people often present with high support needs with advanced ill health and/or cognitive impairment at a young age (young olds).36 The lack of facilities providing palliative care, including respite and a place to die in comfort, were the most significant gaps described.

Homeless people do not fit the profile of the majority of care home patients where one of the admission criteria is usually to be over 65 years of age. Behaviours associated with substance misuse also pose a challenge for hospices and care homes, where many residents are frail and vulnerable. Thus, access to these services is uncommon for this population:

Most care homes are with people with dementia who are older; it’s just, it’s our patients just don’t fit any of these like rigid things … the care homes themselves are like ‘what?! ‘We don’t want this 29 year old’ … you know? (Specialist nurse – Borough C)

Need for holistic approach to care and support

Frustration was expressed regarding the fragmentation and lack of joint approach between health, housing and social services which prevented a person-centred approach to care. Assessments by social services only took the individual’s current situation into account. They were often conducted in hospitals, following detox from alcohol (or stabilisation on methadone), were often inaccurate and did not represent that person’s needs back in the community. When support from social services was obtained, it was often inadequate. Concerns from hostel staff were often not listened to by professionals and a lack of continuity in carers meant trust did not develop between the carer and the homeless person:

They are not incontinent 11 o’clock every day when the carer comes in. It’s like … when somebody is dying … they are not dying between the hours of 9 to 5. It could happen anytime so you know … who does the nights? We do. Their physical health needs are so extensive. So … having these [carers] coming in and out. It’s just … it doesn’t work. (Hostel staff – Borough C)

Hostel as a place of care and death?

In London, many homeless people with high support needs are in homeless hostels, usually for up to 2 years. The hostels included in this research all provide single rooms with shared facilities and an assigned key worker. Overall, key workers focus on recovery; helping people transition to less supported accommodation, moving towards abstinence, stability and employment. For some, this is appropriate, but for those with advanced illness, this raises issues. Shifting the focus of support and services away from recovery towards living well until death (by focusing on improving quality of life) may be uncomfortable, despite recognition that ‘recovery’ may not be possible for all:

When I first came into this I thought this is about recovery, it’s not. I mean … realistically … it can’t be. And it isn’t. Very few people recover. (Specialist nurse – Borough C)

Where the focus of support and interactions between professionals and homeless individuals changed from an aim to reduce or stop substances, to an improvement in quality of life, care was person-centred and compassionate:

He was very content. I think because we allowed him to have his wish [not to go into hospital] … He didn’t want any medication from the GP … he wanted to carry on drinking … we respected his wish … It was very sad for us, but … it was what he wanted. (Outreach worker – Borough B)

Debate emerged over whether homeless people should, if they wished, be supported to remain in hostels until they die. Concerns raised included limited access to adequate support, lack of staff confidence, burden on staff, safeguarding concerns and the chaotic, noisy nature of hostels. The quote below describes fear around the vulnerability of homeless people with advanced ill health who remain within the hostel:

They become so vulnerable to financial exploitation …, they used to take him to the cash machine and take all his money … we couldn’t safeguard against that … he was deemed to have capacity; we couldn’t do a damned thing about his money. (Hostel staff – Borough C)

Storing and administering medication within a hostel was also problematic. Hostel staff are not trained or licensed to administer medication. In an environment in which many residents have substance misuse issues, the safe storage of medications such as opiates is an issue.

Furthermore, some participants felt dying in a hostel may be an isolated, unpleasant experience that could be disturbing for other residents:

You’ve got to walk past those people [who are visibly unwell]. They half block the stairwell, you have to edge your way past. It’s kind of … in your face. Erm, yeah, it becomes part of the furniture. But it disturbs me as a person … (Hostel resident – Borough C)

The burdens of caring for dying homeless people fall on hostel staff, despite often having no medical training or experience. Many participants emphasised that hostels are not, and perhaps should not become care homes. While hostel staff did all they could to support dying residents, this was a very difficult position for them, emotionally and logistically:

At least three times a shift we check she’s okay. It’s hard … particularly on weekends and nights when we only have two staff … it’s a big hostel [60 residents] … you really can only do so much … this isn’t an appropriate environment, but it’s the best we have. (Hostel staff – Borough A)

With the focus of palliative care being quality of life, for some, the benefits of enabling dying persons to remain in hostels outweighed the challenges. Arguments for people remaining in the hostel centred around choice and compassion. Some hostel residents perceived the hostel as ‘home’. As such, if a desire to remain there until death was expressed, some felt this should be honoured. While hospitals may better serve the physical needs of dying homeless people, some felt hostels were best placed to meet their emotional needs. Furthermore, hospitals were often thought of as ‘places of death’ by homeless people and were thus avoided:

I remember one guy … his breath, you’d smell it, you’d know he was ill. And I used to say to him, get help … get to hospital … he just was absolutely terrified of hospitals. He’d say ‘if I go into hospital, I’m coming out in a box’. (Day centre user – Borough B)

Uncertainty and complexity

Difficulty predicting disease trajectories

The surprise question (‘Would you be surprised if this person were to die in the next 6–12 months?’) is a method used when considering whether someone may benefit from palliative care.37 Hostel staff and healthcare professionals indicated that for many homeless people, the answer to this question would be ‘no’. Their health is often poor, and their needs are complex making it hard to identify who might be considered palliative.

Further uncertainty stems from characteristics of illnesses such as decompensated liver disease (often a complication of alcohol and/or hepatitis C), common among the homeless population. Prognosis for these illnesses is notoriously difficult to predict, particularly in the context of continuing substance misuse:38

One of my clients was given three months, he didn’t die for about a year and four months later, that’s liver disease, yeah. And there’s another guy … he should be dead by now. He looks weller every day! (Hostel staff – Borough C)

For illnesses such as cancer, with more predictable trajectories, professionals reported more success in accessing services including hospice support. However, even for homeless cancer patients who were not misusing substances, placement within a care home or hospice remained challenging, due to young age and previous experiences that hospices had with supporting homeless people:

The last time I tried to get a [homeless] patient a bed at a hospice, they [the hospice] interrogated me. They wanted a very clear prognosis and it was because the woman I had sent there before, who we thought was dying … was there for months because she had nowhere else to go. (Hospital palliative care nurse specialist – Borough B)

Advance Care Planning

ACP [or discussions regarding goals of care] rarely occurred with our group of homeless individuals. In addition to a lack of options to offer, professionals often lacked confidence in having such conversations and expressed concerns regarding the fragility and vulnerability of many homeless people:

… we have a client who … probably … could die within the next 6-12 months … do we want to have a conversation about where he wants to die? I feel I can’t because I don’t feel there are any options for him. (Hostel staff – Borough C)

Many homeless people are using substances to block out past trauma, so the potential of negatively impacting on their emotional well-being by discussing future health and options was voiced as a major concern. Other professionals feared discussions about future care needs and preferences may represent removal of hope and be interpreted as staff ‘giving up on them’. Transient relationships were often cited by medical staff as conversation barriers:

For people who aren’t engaging … Self-discharging … nobody feels they know them … having those very difficult conversations … people feel someone else should be doing it … no one feels qualified … (Nurse – Borough C)

Avoidance of discussing future preferences was echoed by homeless people:

A lot of people are frightened to think about it. Most people won’t talk about it, they won’t entertain talking about it. They see it as so far away, you know? Why bother now, let’s wait until nearer the time. (Hostel resident – Borough C)

The combination of apprehension from professionals and avoidance from homeless people challenged the exploration of future wishes and preferences:

I think the temptation is just not to have the conversation, you know it’s happening, they know it’s happening … especially when admissions become more frequent … staff know eventually that person’s not coming back. (Hostel staff – Borough A)

Discussion

This is the largest qualitative study exploring challenges to palliative care for homeless people, from the perspectives of homeless people and those supporting them. This research documents the growing concern that many homeless people are dying in unsupported, unacceptable situations. Complexities of identifying who is palliative and also the lack of appropriate services for homeless people who have high support needs, particularly in combination with substance misuse issues, are highlighted.

Our findings indicate that complexity around caring for homeless people with advanced ill health stems in part from difficulties accepting young people are dying from potentially preventable causes. The conflict between the recovery-focused nature of many services and the realities of health and illness for homeless people create blocks to truly person-centred care.

Implications for policy and practice

Tailored, joined-up services

The importance of individualised care for homeless people21 in a psychologically informed environment39 has been recognised. However, the current fragmentation in services and funding across London means this can be challenging to deliver, with access to appropriate services proving problematic.

Providing adequate support for homeless people as their health deteriorates is complicated and requires an integrated approach between health, housing and social care. In the United Kingdom, a facility that is tailored to the needs of this population that could provide respite,40 act as a step-up from a hostel and a step-down from hospital and which could also be a place someone could peacefully die is required. This model is in operation in Canada in the form of a ‘shelter based hospice’.41

Promoting in-reach, collaboration and training

If homeless people with advanced ill health are to remain in hostels, greater collaboration between health- and social-care services is needed. This could improve care for homeless people with advanced ill health and support and reduce pressure on hostel staff. Participants emphasised the need for multidisciplinary case reviews, in-reach into hostels and greater training and support for all professional groups. Where there was in-reach from nurses and general practitioners into hostels, this was found to be invaluable. Also of great benefit was the palliative care coordinator role, operational in St Mungo’s hostels (a homelessness charity).19 This provides an interface between hostels and healthcare providers and encourages multidisciplinary working. Extension of this and other in-reach roles should be encouraged, alongside building on the growing interest from the hospice community in supporting homeless people.

ACP

Conversations with homeless people regarding their future care preferences rarely occur partly due to uncertainty of prognoses, concerns about fragility and the focus on recovery inherent in the ethos of many services. To combat these, we propose that conversations start earlier and the focus of such discussions should help people explore their insights, aspirations, health and choices for the future, and not just end-of-life issues.

Strengths and limitations

While the experiences of homeless people in London may be different to those in rural areas, we believe many of the challenges described may be encountered outside London. A large, diverse sample was recruited, though self-selection of professional participants and key worker identification of homeless participants introduces the potential for bias. The requirement for homeless people to be sober during participation may have led to an underrepresentation of those with severe addictions. Twenty-five percent of our homeless sample reported using drugs, which is lower than previous UK research suggests.6

Implications for future research

Significant gaps in services for homeless people with advanced ill health have been identified. Research is needed to quantify the scale of this problem and interventions, using qualitative and quantitative methods, need to be developed and evaluated to address this inequity. Training for all professional groups needs to developed, delivered and evaluated.

Conclusion

Given the unique and complex needs of homeless people with advanced ill health, specialised, flexible services are key in promoting compassionate, coordinated care. This will require a joint response from health, housing and social services. At the minimum, this should include increased collaboration between services, the promotion of in-reach into hostels and greater training and support for all professional groups. A bespoke service, providing an appropriate level of care and support for homeless people who are dying, in an environment in which they can feel comfortable may also be required.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the managers, employees and service users of homelessness services across the three London Boroughs. C.S., P.S., S.D. and J.L. conceptualised the study. C.S., B.F.H. and J.D. collected the data. B.F.H. and C.S. analysed the data. B.F.H. drafted the initial manuscript. C.S., P.S., J.L., N.H., D.H., J.D., B.V., S.D., N.B. and P.K. reviewed the manuscript, approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by a grant from The Oak Foundation (OCAY-14-574). PS, BV, JL and SD were supported by Marie Curie (grant numbers: 509537; 531645 and 531477). Initial seed funding and support was provided by Coordinate My Care to facilitate CS in the development of this research.

References

- 1. Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, et al. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ 2009; 339: b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Homeless Link. Support for single homeless people in England: annual review 2015. London: Homeless Link, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, et al. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health 2010; 100(7): 1326–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrow SM, Herman DB, Córdova P, et al. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health 1999; 89(4): 529–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzpatrick S, Pawson H, Bramley G, et al. The homelessness monitor: England 2016. London: Crisis, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Homeless Link. The unhealthy state of homelessness: health audit results 2014. London: Homeless link, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stringfellow EJ, Kim TW, Pollio DE, et al. Primary care provider experience and social support among homeless-experienced persons with tri-morbidity. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2015; 10(Suppl. 1): A64. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Homeless Link. Improving hospital admission and discharge for people who are homeless: analysis of the current picture and recommendations for change. London: Homeless Link and St Mungo’s, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, et al. Health care utilization among homeless adults prior to death. J Health Care Poor U 2001; 12(1): 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davis-Berman J. Serious illness and end-of-life care in the homeless: examining a service system and a call for action for social work. Soc Work Soc 2016; 14(1): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rae BE, Rees S. The perceptions of homeless people regarding their healthcare needs and experiences of receiving health care. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71(9): 2096–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Håkanson C, Öhlén J. Illness narratives of people who are homeless. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2016; 11: 32924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNeil R, Guirguis-Younger M. Illicit drug use as a challenge to the delivery of end-of-life care services to homeless persons who use illicit drugs: perceptions of health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNeil R, Guirguis-Younger M, Dilley LB, et al. Harm reduction services as a point-of-entry to and source of end-of-life care and support for homeless and marginally housed persons who use alcohol and/or illicit drugs: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tobey M, Manasson J, Decarlo K, et al. Homeless individuals approaching the end of life: symptoms and attitudes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cipkar C, Dosani N. The right to accessible healthcare: bringing palliative services to Toronto’s homeless and vulnerably housed population. UBC Med J 2016; 7(2): 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hudson BF, Flemming K, Shulman C, et al. Challenges to access and provision of palliative care for people who are homeless: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15(1): 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song J, Bartels DM, Ratner ER, et al. Dying on the streets: homeless persons’ concerns and desires about end of life care. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22(4): 435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davis S, Kennedy P, Greenish W, et al. Supporting homeless people with advanced liver disease approaching the end of life. Marie Curie and St Mungo’s, 2011, https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/commissioning-our-services/current-partnerships/st-mungos-supporting-homeless-may-11.pdf

- 20. McNeil R, Guirguis-Younger M, Dilley LB. Recommendations for improving the end-of-life care system for homeless populations: a qualitative study of the views of Canadian health and social services professionals. BMC Palliat Care 2012; 11: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sumalinog R, Harrington K, Dosani N, et al. Advance care planning, palliative care, and end-of-life care interventions for homeless people: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2017; 31: 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henry C. Advance care planning: a guide for health and social care staff. Nottingham: The University of Nottingham, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song J, Ratner ER, Wall MM, et al. Summaries for patients. End-of-Life Planning intervention and the Completion of Advance Directives in homeless persons. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153(2): I–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song J, Ratner ER, Wall MM, et al. Effect of an End-of-Life Planning Intervention on the completion of advance directives in homeless persons: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153(2): 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leung AK, To MJ, Luong L, et al. The effect of advance directive completion on hospital care among chronically homeless persons: a prospective cohort study. J Urban Health 2017; 94: 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leung AK, Nayyar D, Sachdeva M, et al. Chronically homeless persons’ participation in an advance directive intervention: a cohort study. Palliat Med 2015; 29: 746–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. CHAIN annual report: Greater London April 2015 – March 2016. Greater London Authority, 2016, https://files.datapress.com/london/dataset/chain-reports/2016-06-29T11:14:50/Greater%20London%20full%202015-16.pdf

- 28. Bhatti V, Currie D, Sapsaman T. Atlas of services for homeless people in London. London: Housing Foundation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bax A, Hewett N. Pathway annual report, 2015, http://www.pathway.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Pathway-Annual-Report-2015.pdf

- 30. Finlayson S, Boelman V, Young R, et al. Saving lives, saving money: how homeless health peer advocacy reduces health inequalities. London: The Young Foundation, Groundswell, The Oak Foundation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. St Mungo’s Broadway Apprenticeship Scheme (press release), 2015, http://www.mungos.org/apprenticeship_scheme

- 32. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oliveira DL. The use of focus groups to investigate sensitive topics: an example taken from research on adolescent girls’ perceptions about sexual risks. Ciên Saúde Colet 2011; 16: 3093–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ko E, Nelson-Becker H. Does end-of-life decision making matter? Perspectives of older homeless adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 2014; 31(2): 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Homeless Link. Old before their time (press release). London: Homeless Link. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lilley EJ, Gemunden SA, Kristo G, et al. Utility of the ‘surprise’ question in predicting survival among older patients with acute surgical conditions. J Palliat Med 2017; 20: 420–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rakoski MO, Volk ML. Palliative care for patients with end-stage liver disease: an overview. Clin Liver Dis 2015; 6(1): 19–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ritchie C. Prevent rough sleeping; create a psychologically informed environment. Therapeutic Communities 2015; 36(1): 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dorney-Smith S, Hewett N, Burridge S. Homeless medical respite in the UK: a needs assessment for South London. Br J Healthc Manag 2016; 22(8): 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Podymow T, Turnbull J, Coyle D. Shelter-based palliative care for the homeless terminally ill. Palliat Med 2006; 20(2): 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]