Abstract

Background:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans (LGBT) people have higher risk of certain life-limiting illnesses and unmet needs in advanced illness and bereavement. ACCESSCare is the first national study to examine in depth the experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness.

Aim:

To explore health-care experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness to elicit views regarding sharing identity (sexual orientation/gender history), accessing services, discrimination/exclusion and best-practice examples.

Design:

Semi-structured in-depth qualitative interviews analysed using thematic analysis.

Setting/participants:

In total, 40 LGBT people from across the United Kingdom facing advanced illness: cancer (n = 21), non-cancer (n = 16) and both a cancer and a non-cancer conditions (n = 3).

Results:

In total, five main themes emerged: (1) person-centred care needs that may require additional/different consideration for LGBT people (including different social support structures and additional legal concerns), (2) service level or interactional (created in the consultation) barriers/stressors (including heteronormative assumptions and homophobic/transphobic behaviours), (3) invisible barriers/stressors (including the historical context of pathology/criminalisation, fears and experiences of discrimination) and (4) service level or interactional facilitators (including acknowledging and including partners in critical discussions). These all shape (5) individuals’ preferences for disclosing identity. Prior experiences of discrimination or violence, in response to disclosure, were carried into future care interactions and heightened with the frailty of advanced illness.

Conclusion:

Despite recent legislative change, experiences of discrimination and exclusion in health care persist for LGBT people. Ten recommendations, for health-care professionals and services/institutions, are made from the data. These are simple, low cost and offer potential gains in access to, and outcomes of, care for LGBT people.

Keywords: Sexual orientation, gender history, advanced illness, bereavement, qualitative, inequalities

What is already known about the topic?

People who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans (LGBT) have an increased risk of certain life-limiting illnesses.

Despite recent legislative change and policy recommendations to improve care, LGBT people continue to experience discrimination and exclusion in health-care settings.

Previous studies have identified unmet health and bereavement care needs for LGBT people.

However, outside of the context of HIV, no previous studies have examined these experiences from the perspectives of LGBT people facing advanced illness, and it is unclear how best to improve care.

What this paper adds?

ACCESSCare was the first study with the aim of examining these inequalities in depth from the perspectives of LGBT people facing advanced illness, not limited to HIV/AIDS.

LGBT participants described barriers to accessing care, in the context of advanced illness, at multiple levels: internalised; interactional (in clinical encounters) and service level.

While basic clinical needs of comfort and being pain free are common to all individuals facing advanced illness, for our trans participants, there were additional clinical considerations.

LGBT people also face further stressors at societal levels, increased isolation and family estrangements and additional legal concerns.

We also identified facilitators to good care at a service and interactional level, including overtly acknowledging and including partners in critical decisions.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

There is a need for focused efforts to improve care experiences for LGBT people through public health strategies to address issues in accessing care and training and education, to address deficits in care delivery.

Ten recommendations for individual health-care professionals and services or institutions are made from the data. These are simple, low cost and grounded in the evidence and offer potential gains in access to, and outcomes of, care for LGBT people.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans (LGBT) people have specific health-care needs. Lesbian women and gay men have greater all-cause mortality than heterosexual people.1 LGBT people have a higher risk of certain cancers,2–7 are less likely to attend for routine screening8,9 and more likely to present with more advanced disease. LGBT people have higher rates of mental illness10 and risk behaviours (drinking, smoking and drug use) that are linked to discrimination.11,12

In recent years, there have been a series of legislative changes in the United Kingdom to support the rights of LGBT people. These have included, but are not limited to, the Civil Partnership Act (2004), the Gender Recognition Act (2004), the Equality Act (2010) and Same-Sex Marriage (2014). Globally, an increasing number of countries recognise same-sex unions; however, many countries offer no legal protection, and particularly across Africa and Asia, criminalisation and persecution for LGBT people remain a reality. Despite policy initiatives to improve health care for LGBT people,13–16 discrimination within health and social care services remains common.17 LGBT people describe heterosexual and/or cisgender (where gender identity corresponds with birth sex) biased environments, inadequate support and failure to involve partners in critical health decisions.18 Indeed, a recent international survey found implicit preferences for heterosexual people versus gay and lesbian people by heterosexual health-care providers.19 LGBT people describe additional challenges in bereavement, including lack of acknowledgement of their loss, additional legal issues, exclusion of ‘chosen family’ as part of the unit of care and the continued shadow of HIV/AIDS.20

Previous negative health-care experiences and health disparities for LGBT people impact on their access to care and timely treatment,8,21 resulting in worse health-care experiences and poorer general health.22 Furthermore, if a couple have felt unable to disclose their relationship, the bereaved partner’s needs may not be recognised, resulting in prolonged or disenfranchised grief,23 poor bereavement outcomes20 and increased mortality risk.24

LGBT people represent a significant minority. Conservative UK estimates suggest 5%–7% of the population identify as LGB25 and 1% as trans,26 although fears of disclosure are associated with persistent underreporting. Health disparities and discrimination for LGBT people must end,27,28 but evidence to inform this change is limited.

When facing advanced illness, there is a need for person-centred care, to ensure preferences and priorities for care and decision-making are met. When an individual has one or more conditions that result in a decline in general health and deterioration in function, which will continue until the end of life, this can be described as advanced illness.29 Care within the context of advanced illness requires a person-centred approach, with effective and open communication with the patient and those close to them throughout their illness. Although previous studies have explored discrimination in health care for LGBT people, to our knowledge, no previous studies have examined these inequalities through the experience of LGBT people facing advanced illness, not limited to HIV/AIDS. This study aimed to explore health-care experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness to elicit: views regarding sharing identity (sexual orientation/gender history); experiences of accessing services, discrimination and exclusion; and examples of best practice, to generate recommendations to improve care.

Methods

We conducted a national in-depth qualitative interview study.

Recruitment

People who identified as LGBT and were facing advanced illness were recruited to the study. This included individuals facing advanced illness themselves, informal carers (partners, friends and family) and bereaved information carers. The decision to include current and bereaved informal carers was guided by the ethos of palliative care to support the individual, and those close to them, through advanced illness and into bereavement. This would enable a more thorough understanding of the experience of advanced illness for LGBT people.

Inclusion criteria: ⩾18 years; identified as LGBT; facing advanced illness and potentially in the last year of life (defined as ‘no’ in response to the surprise question, ‘Would you be surprised if this person died with 12 months?’, in conjunction with general indicators of decline and specific clinical indicators related to their condition30); or current/bereaved unpaid caregiver of LGBT person facing advanced illness.

Exclusion criteria: too unwell/distressed to complete interview; unable to give informed consent. To minimise distress in the acute post-bereavement period, individuals were not approached about the study until >4 months post bereavement (in line with previous post-bereavement research31,32). Where bereaved individuals self-referred to the study before 4 months, they were encouraged to consider delaying the interview, unless they expressed a clear preference to share their experiences. On these occasions, the interview was scheduled in line with their wishes.

Participants were recruited through six UK palliative care teams (three hospital and three hospice) and nationally through social/print media and LGBT community networks. LGBT individuals facing advanced illness who had shared their LGBT identity with the palliative care team were invited to participate. For media/community recruitment, individuals self-referred in response to adverts. Media/community recruitment was used to give the opportunity to participate in the study to individuals who may not feel comfortable to share their identity with their health-care teams and to enable recruitment across the United Kingdom in urban and rural settings. Individuals were purposively sampled by sexual orientation, gender identity, age and illness (cancer/non-cancer). For lesbian and gay participants, recruitment continued until data saturation was achieved33 (no new themes emerging from the data). Due to smaller number of people identifying as bisexual and trans, data saturation was not expected. Interviews occurred in the participant’s chosen location: home (n = 26), hospital/hospice (n = 9), public spaces (cafe, library, park and hotel lobby; n = 4) or by telephone (n = 1).

Interviews

The semi-structured interview schedule was guided by a systematic literature review,18 project advisory group and LGBT charity partners. Interviews commenced with demographic questions (age, sexual orientation, gender identity and relationship status). Participants were then invited to share their narrative, from illness onset to present day. The interviewer (K.B.) used prompts and probes to elicit further information about care settings, teams and current/future care needs. The interviews also explored the following: experiences/views regarding disclosing identity to health-care professionals, involvement of partners in consultations, support structures (biological/non-biological family and friends), barriers to accessing care and recommendations for health-care professional training. Interviews were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, with allocation of pseudonyms to preserve anonymity. A reflexive diary was completed to record key emergent themes; contextual information; and personal and/or methodological reflections, which shaped subsequent interviews.

Analysis

Interviews were analysed (K.B./R.H.) using inductive thematic analysis, in five stages: familiarisation, coding, theme development, defining themes and reporting. Analysis was informed by theories of palliative care (specifically consideration of the four holistic domains of palliative care: physical, psychological, social and spiritual),34 although themes were derived from the data. A re-iterant process of discussing areas of agreement and disagreement was used, with particular attention paid to cases where emerging themes contradicted more common ideas. Themes were reviewed by the project steering group, including LGBT charity partners. Recommendations for practice were generated from the data. Analysis was supported using NVivo (V.10), and reporting was in line with the guidelines from the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ).35

Results

Participants

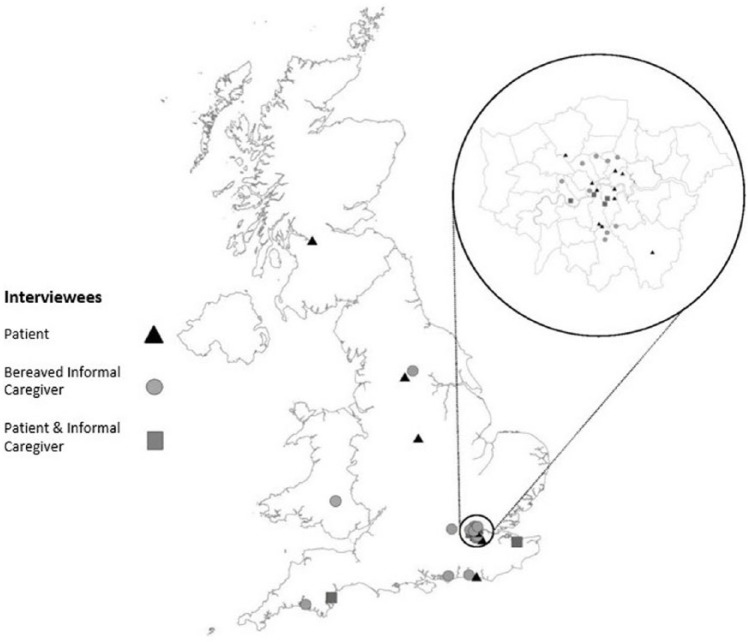

In total, 40 LGBT people from across the United Kingdom (Figure 1) were recruited (n = 21 referred by clinical team and n = 19 self-referred to study) and interviewed (November 2014–January 2016). Participants were facing advanced illness themselves (n = 20) or current (n = 6) or bereaved (n = 14) unpaid caregivers of an LGBT person with advanced illness.

Figure 1.

Recruitment to the ACCESSCare study.

Participants self-identified as gay (n = 19), homosexual (n = 1), gay and intersex (n = 1), lesbian (n = 14), bisexual (n = 2), lesbian and trans (n = 2) and friend of a trans woman (n = 1). Participants described experiences related to cancer (n = 21), non-cancer conditions (n = 16) and both cancer and non-cancer conditions (n = 3). In total, 34 participants were White British, 4 White Other, 1 Black British and 1 African-Caribbean (see Table 1). Median age was 59 years (range: 27–94 years). Median interview duration was 73 min (range: 19–152 min).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Participant type | |

|---|---|

| LGBT person living with advanced illness themselves | 20 |

| Unpaid caregiver (partner) | 5 |

| Unpaid caregiver (friend) | 1 |

| Bereaved unpaid caregiver (partner) | 13 |

| Bereaved unpaid caregiver (friend) | 1 |

| Identity: sexual orientation and/or gender history (self-described) | |

| Gay man | 19 |

| Homosexual man | 1 |

| Gay intersex man | 1 |

| Lesbian woman | 14 |

| Bisexual woman | 2 |

| Trans lesbian woman | 2 |

| Friend of trans woman | 1 |

| Ethnicity (self-described) | |

| White British (including White English and White Scottish) | 34 |

| White Other (African, American, Australian and New Zealand) | 4 |

| Black British | 1 |

| African-Caribbean | 1 |

| Diagnoses | |

| Cancer: including lung, prostate, myeloma, bowel, ovarian, breast, cervical, transitional cell, head and neck, liver, pancreatic and endometrial | 21 |

| Non-cancer: including lung disease (interstitial lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary fibrosis), neurological conditions (motor neurone disease, Parkinson’s, dementia, cerebellar ataxia and brain tumour), HIV and renal failure | 16 |

| Living with both cancer and non-cancer conditions | 3 |

| Age | |

| 20s, 30s, 40s | 7 |

| 50s, 60s | 27 |

| 70s, 80s, 90s | 6 |

| Location – referred to study by local palliative care team | |

| Greater London | 21 |

| Location – self-referred to the study | |

| Greater London | 6 |

| South West | 3 |

| South East | 3 |

| Midlands | 2 |

| North of England | 3 |

| Wales | 1 |

| Scotland | 1 |

LGBT: lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans.

Findings

Overview

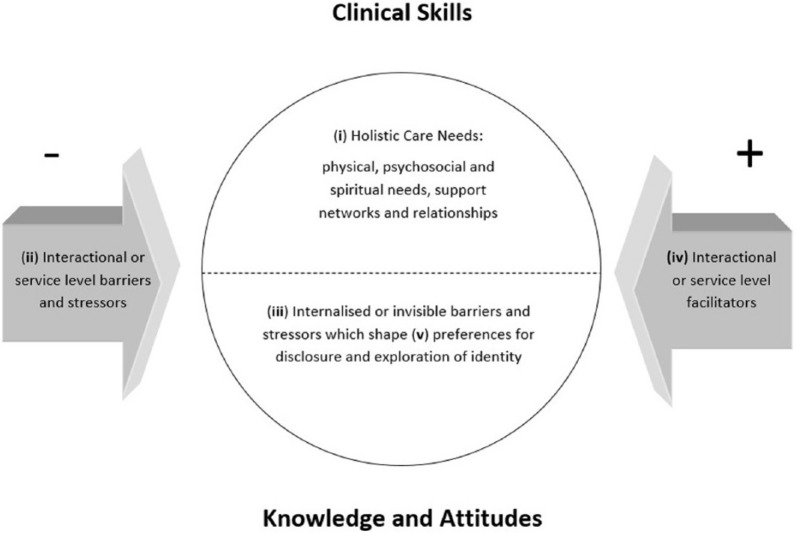

Five broad themes emerged from the interviews regarding the experience of receiving care for LGBT individuals facing advanced illness (see Figure 2): (1) LGBT people with advanced illness may have care needs that require additional or different consideration. (2) Also, in clinical encounters, their experience may be negatively affected by interactional (created in the encounter) and service-level barriers and stressors. (3) Additionally, LGBT people may experience internalised or invisible barriers and stressors which may not emerge, or may not be apparent, within the encounter. (4) Their experiences can also be positively affected by interactional and service-level facilitators. (5) However, fears and/or experiences of discrimination, stemming from the legacy of discrimination and lack of legal protection, shape preferences for identity disclosure. Awareness of these potential barriers, and how they may shape care experiences and access to services, is dependent on the knowledge and attitudes of health-care professionals. Health and social care professionals must be trained to anticipate these potential barriers that shape access to, and experiences of, services. Each theme is described in detail below, with example quotes from the verbatim transcripts.

Figure 2.

LGBT experiences when facing advanced illness: considerations for the clinical encounter.

Person-centred care

Clinical needs

Participants described the universal needs of individuals facing advanced illness, irrespective of sexual orientation or gender identity: comfort, safety and being pain free:

I think it’s no different. Because in every relationship, everybody has their role … and to know where the resources are within that relationship, that is more important than actually trying to look inside a box called lesbian, gay, transsexual, and saying, ‘Right, what do I pick out of that box?’ It’s about what’s outside of that box in terms of healthcare. What does everybody want? We want to be healthy. We want to be happy. We want to be content. We want to be comfortable. We want to be pain-free. We want all the things that everybody else who is a mammal, feeling thing, wants. (Elaine, aged 61, bisexual woman, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

While participants recognised these commonalities, they also highlighted the importance of person-centred care addressing their needs and preferences. Importantly, participants did not suggest their needs required LGBT bespoke services but that health-care professionals may need to think carefully, and perhaps a little differently, to ensure equity in care delivery. For example, the trans participants described additional clinical considerations related to their gender history, specifically interactions between treatments provided by the gender clinic and those for their illness. Both trans women interviewed were living with lung conditions and had experienced refusal of gender confirmation surgery (i.e. surgery to bring physical characteristics more in line with gender identity) due to their illnesses and associated anaesthetic risk:

I may be getting towards end-stage, I may be life-limited. I’m not terminal in my eyes, and I’m not ready to die. I want my surgery first, and I was hanging on in there; my surgery before I died. It was important to me to be buried as a woman, not half and half, you know, with the physical side of it. (Louise, aged 51, trans woman living with lung disease)

However, these interactions also impacted in the reverse, with hormone therapies affecting their lung health. Discussions which required individuals to prioritise, and ultimately choose between, treatments to preserve their health or gender identity were unique to our trans participants:

Taking oestrogen increases the risk of blood clots. So now I’ve got these blood clots, I had a conversation with a consultant. The logical thing to do is to stop taking them to reduce the risk to a minimum for the future. So then we had to talk about how important it was psychologically, and I said that I think it is very important. I mean if someone said, ‘Your heart will stop in 10 minutes if you don’t stop taking them’, I’d stop, but I had to work with the gender clinic people and they said there is an elevation of the risk but it’s acceptable. It’s easy for somebody else to say it’s acceptable, I know, but, so we carried on. (Bridget, aged 68, trans woman living with lung disease)

Social needs and support structures

Participants also described additional needs related to their support structures. Many described isolation or family estrangements, heightened in bereavement:

The prognosis was shattering frankly. There is a slightly different dynamic between two women who had never even considered having a family as it really ‘wasn’t done’. You’re perhaps bound up in each other rather more to the exclusion of others. (Nicola, aged 68, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Those in same-sex relationships described lack of recognition of their bereavement from their social network and wider society:

It feels that society doesn’t validate the loss of a civil partner quite as much as they would understand and validate the loss of a husband. It’s more complicated, and a lot of people don’t have the imagination to understand that it’s the same kind of relationship … Before I would have said I was civil partnered but now I was civil partnered, but now what am I? I am a gay widow. That’s not normal … You know? So that’s quite isolating. Because that’s quite, it’s a bit weird a bit unique, which I don’t particularly like. But that’s how it is. Yeah, I don’t think we are quite there yet you know. We’ve come a long way but society is not quite there yet. They don’t have the language for it yet. (Rebecca, aged 38, bereaved partner of bisexual woman who died of cancer)

This was compounded by society’s lack of language to describe that loss. One participant expressed uncertainty as to whether to describe herself as a widow and her access to the social resources and expectations that accompany that descriptor. Participants also described the double taboo of bereavement and same-sex relationships, with acquaintances less likely to broach the subject of their loss:

I do think there is a difference, you can’t be as open. But then having experienced the death of my father years ago, it’s death that people struggle with, and if you then add a layer about somebody’s sexuality, I think that makes it even more complicated for people because they’re not sure how to respond. (Melanie, aged 54, bereaved partner of a lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Our bereaved bisexual participants also described additional challenges in bereavement, particularly the internal struggle of redefining oneself as bisexual, after the loss of long-term same-sex partner:

I think my relationship has been the calmest, most content chunk of my life. So losing that has thrown me back into a kind of chaos state, where I’m now having to redefine who I am as a bisexual woman, and not taking into account any of the other experiences that I’ve had. I’m having to define myself, and I find that really difficult. But until I know that, I’m just living day to day and coping with what I need to cope with, which is a lot. (Elaine, aged 61, bisexual woman, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Legal concerns

Lack of recognition of relationships was also described regarding legal issues. LGB participants in relationships, but not civil partnered/married, recounted concerns regarding recognition as next-of-kin and involvement in decisions:

We’re not in a formal partnership at the moment, for a variety of reasons that’s not happening in the near future but ((2 second pause)) and of course being in a formal partnership and being able to wave your papers is the easiest and quickest way of being recognised as next of kin and err ((4 second pause)) and ((sigh)) and we’ve got to work on that but I suspect that straight couples don’t actually have to wave their marriage lines. (Carol, aged 70, partner of lesbian woman living with cancer and lung disease)

Additional concerns for trans participants related to acquisition of a gender recognition certificate to legally recognise their gender and importantly for their gender to be correctly identified on their death certificate and in memoriam. For those facing advanced illness, there was concern that the certificate would not be acquired in time:

Not everybody applies for the Gender Recognition Certificate … They don’t necessarily feel the need for it … [but] you can’t have a death certificate in the right name. (Anna, friend of a trans woman living with lung disease)

Interactional or service-level barriers and stressors

Interactional

Participants also described interactional stressors created in the consultation with health-care professionals, varying from heteronormative assumptions or insensitivity, to overt homophobic or transphobic behaviours. Many described heteronormative assumptions from health-care professionals, which, although not necessarily distressing, created a distance between the patient and health-care professional:

It’s usually been … if they’re sort of getting background … They don’t ask you about your sexuality, they ask about your heterosexuality, umm, do you have children? … or, which is, you know, is not, is not an offence. Do you have children. It’s a simple question. But it, it, creates that tiny little bit of distance … Which is saying, I’m heterosexual and I wonder what your experience of heterosexuality is … And it’s perfectly fair, perfectly, it’s not, it doesn’t offend me or anything like that. But it says I’m different … ((10 second pause)) Basically it’s, it’s referring to sexuality as sexuality when in fact it’s heterosexuality … and it’s speaking in ways that assume that you already share that sexuality, rather than coming at the topic with an open mind that you might be gay. (Andrew, aged 67, gay man living with cancer)

More overt homophobic behaviours, included refusal to acknowledge the relationship with a same-sex partner:

There was complete lack of recognition. The consultant even, on the tenth or twentieth time of being told I was his partner still referred to me as his brother. (James, aged 35, partner of gay man living with a neurological condition)

These experiences were damaging for the patient and their partner, creating unnecessary additional stress. Others experienced lack of recognition of the nature, depth and duration of the relationship by health-care professionals:

I’ll tell you one other thing that was a fright and really offended me was had a had a visiting chap from the hospice um and he was, he was doing the first home visit. And he was a Locum and he sort of breezed in up the stairs and I was there as Grace had asked me to be, um and he asked something and I answered him and he said ‘no, you tell me’ he said ‘never mind the hangers on’ and I just thought ‘hangers on’ ((laughs)) ‘you don’t have a clue!’ (Nicola, aged 68, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Such experiences were particularly challenging when discussing emotive issues such as prognosis:

He totally ignored me. It was as though I wasn’t there really … [later in the interview] … I think the word ‘include’ is the key word, is to keep the partners included in what’s going on … like that neurosurgeon totally sort of didn’t connect with the fact that we were a couple, as he might have done if we were a husband and wife. He was oblivious to the whole thing. It’s seeing that we are a couple and remembering the fact that we might have been … You know, we’ve been together for 24 years, which is a lot more than a lot of marriages last and it’s being included in the decisions and what’s going to happen and what’s happening next. (Michael, aged 59, partner of gay man with a neurological condition)

One trans participant also shared experiences of transphobic behaviours including a clinician’s refusal to use the appropriate pronoun:

Two, three, probably three occasions where somebody has used the wrong pronoun … I think culturally it was probably a difficult, concept for him to grasp … I think he read that I wasn’t taking [my health] seriously … but I was trying to basically say, ‘Look I’m distracting myself from this because it’s worrying me’ … and then he called me ‘Mr’ or referred to me as ‘Mr’ to his underlings around the bed … And I took exception to it …, he did it again, and I thought, I, just don’t care anymore. So launched at him telling I didn’t think his qualities as, his interpersonal skills were any good. (Bridget, aged 68, trans woman living with lung disease)

The other trans participant described insensitivity regarding disclosure of her identity in an open ward setting. This was very distressing at a time when she already felt vulnerable and was entirely avoidable:

I’ve been in resus where I didn’t know if I was going to survive the event or not … where it has ten bays with ten patients, just with curtains. And you can hear every conversation … Some doctors have said to me, ‘How long have you been transgendered for?’ And everybody has heard. As much as I can’t breathe, I’m like, ‘What the fuck?’ And I’m lying there like, ‘I don’t want to be talking about this’. Do you know what I mean? And they’ve got no right to say that out loud in front of all the other patients. (Louise, aged 51, trans woman living with lung disease)

Service level

Participants also described barriers at a service level relating to availability of support services and choice of care settings. They described a lack of LGBT friendly support services or being unaware what might be available to them:

Not knowing what’s out there … how do I know what question to ask? … That’s the difficulty that I have … if somebody came up to and said, ‘Right, OK, XYZ that’s what you’ve got in front of you’ … Then I can start asking the right questions … and I finish up spending an hour of somebody’s time just trying to work out what’s good for me. Because nobody’s told me what’s out there. Nobody’s bothered to sit down and really talk about what’s going on and what’s out there what sort of support groups are out there. Umm, I’ve had to sort of muddle my way through, just to find out things. (Edward, aged 64, gay man living with HIV and cancer)

Negative reactions from other people attending the service were also a concern, with participants describing a reluctance to attend care and support services unless explicitly made aware that the service is LGBT friendly:

If somebody had actually rung me, rather than it just coming in the post, and said, ‘Look Fiona, this is what this group does, this is how it works. You might find this helpful. If you would like to go I’ll be there to meet you and I’ll just come in with you on that first one, it will be fine. The person who is leading it will know that you are in there and that you are in a same sex relationship’. If I’d had that sort of security because otherwise that sense of, ‘Oh God, I’ve got to go through this again. I’ve got to come out again. How are people going to treat me?’ It’s tiring. When you are so low and so vulnerable it’s that risk versus benefit equation. (Fiona, aged 53, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

However, for many, sexual identity or gender history was not the only, or most important, identifier when choosing support groups or care settings, reflecting the multidimensionality of identity:

I longed to be in a support group, and I asked the hospice if there were any, and they said no. I said, ‘Has anybody just lost a partner young?’ and they said, ‘No. They’re all old’. Again, I don’t think it would have mattered to me that it was a gay support group, but what was lacking were people who’d lost their partners young. (Rebecca, aged 38, bereaved partner of bisexual woman who died of cancer)

One participant spoke about this in terms of meeting the needs of her and her partner’s Jewish and lesbian identities:

That’s an issue for us as Jewish women as its going to be you know, as lesbian women … And you know, choosing that and because … there are Jewish erm sheltered housing schemes … It’s got a very good reputation but it is mainly run by the, not the erm Hassidic community by certainly by the reasonably orthodox … community. Of which we are not a part. (Marie, aged 59, lesbian woman living with cancer and lung disease)

For many older participants, fear of discrimination in care settings was an overwhelming concern. This forced them to consider concealing their identity or to avoid institutional care settings entirely. This strongly influenced care preferences; many individuals had previously spent years concealing their identity and were reluctant to return to that hidden life:

I really don’t want to go into a place where, you know, I’m the only gay guy … it would be so nice to be in place where you know, I could reminisce about ex-partners. (David, aged 62, gay man living with a neurological condition)

Our trans participants also described fears regarding the provision of intimate care. Due to the nature of care services, often those receiving care at home would not know who would be attending until they arrived, creating an ongoing sense of fear and anticipation associated with disclosure:

It’s the humiliation of the personal care because there is a care thing that goes from social worker to care team. And I’ve been fearful that girls are going to walk in here who hadn’t been pre-warned about … when I hadn’t had the genital surgery … And I feel hurt because I’m aware that in the background some sort of process is happening without my knowledge, without my acceptance. I haven’t been involved in a discussion … But then would it have done any good if I had been involved in the discussion? Because it might cause more anxiety, being part of the process … Does that make sense? … Yes, so it’s not a win-win; it’s a lose-lose. And either way you become anxious. (Louise, aged 51, trans woman living with lung disease)

Internalised or invisible barriers and stressors

Participants shared personal or historical experiences of homophobia or transphobia that travelled with them during their illness and shaped their preferences for disclosing their identity with health-care professionals. For some, experiences spanned decades from a period when their relationships were illegal. Exploration of relationships by health-care professionals needs to be undertaken mindful of these potential experiences of fear, stigma and isolation:

I don’t have a partner. I looked after my mother for 30 years. I sacrificed one for another … The only great thing I did in my life was to see her life through, to a peaceful sleep, calm and happiness, and comfort. I’m proud of that. But myself ((4 second pause)) as they say there are no happy endings … Life is like that. You learn to live with it … It happened only once. ((4 second pause)) and he died … we were lovers in the army when he was 27 and I was 24. And we were, about a year I suppose, 18 months. It was deep. But circumstance happened after the war, I was in hospital for 3 years, he went his way, he married. Two years ago when he must have been 90 something, I phoned him up. And his wife answered the phone and I said ‘is James there?’ she said ‘he’s dying’ I said ‘give him my love if he remembers me’ she said ‘he will’. It’s the luck of the draw. I’ve been incredibly happy, I’ve been intensely happy all my life. I’ve been positive till now. (Ian, aged 94, gay man living with cancer)

Many had previously experienced homophobic or transphobic negativity, discrimination or violence in response to disclosure. These fears continued to be carried with them but were heightened with the frailty of advanced illness:

I am more nervous around men and I am more frightened since I have transitioned because I am not sure if they are going to abuse me, attack me. I am more fearful of physical assault than anything. Because of my COPD, and I live with oxygen, and I know that I cannot run and I cannot move, I am not able to fight or fly. So I am more wary, does that make sense? (Louise, aged 51, trans woman living with lung disease)

Such deep-rooted fears also impacted upon individual’s ability to show intimacy or affection with their partner in care settings, even when their partner was critically ill or dying:

I would say that I felt more self-conscious … We felt way more self-conscious being a gay couple on a ward that was open with other people from the public. We were much more relaxed when he had his own room, which he often did. I don’t necessarily think that was because anyone said anything to us while we were on a ward but it’s still something that you’re … I don’t think we necessarily compromised our relationship but we wouldn’t have probably been as openly expressive to each other with the curtain drawn … I never really necessarily felt that that was to do with the staff. It was more to do with … just life, just how things are, that even though we’ve moved on a lot there are still people that don’t really … It’s just difficult to know … I don’t have an example of anyone being outwardly homophobic on a ward but you’re just more conscious of it as a gay couple on a very big, open ward. (Gary, aged 39, bereaved partner of gay man who died of cancer)

Interactional or service-level facilitators

Interactional

Participants also described occasions where they felt well supported by health-care professionals; their identity was recognised, acknowledged and respected. They shared examples where these were facilitated interactionally, through discussions with health-care professionals:

Expect to be treated equitably … expect to be treated as a couple … There’s something about having the confidence for it not to be an issue, because you don’t want to have to deal with that as an extra worry, as an extra concern, as something that inhibits anybody asking questions, or getting the right kind of answers. (Pauline, aged 63, bereaved partner of bisexual woman who died of cancer)

Simple ways that respect and acknowledgement were achieved interactively included asking about the partner, overtly acknowledging the nature and importance of their relationship:

I was absent once, because I was doing a course of my own at the time, running in tandem with what was going on at home. I needed to be at college to do a presentation, and I couldn’t be there for one of her appointments. The surgeon asked where I was and why I wasn’t there, and that kind of thing. So yes, it was noticed when I wasn’t there. (Elaine, aged 61, bisexual woman and bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Health-care professionals’ overt recognition of the depth and duration of the relationship, and the need for intimacy and closeness, was also central to positive experiences:

I think one of them even lifted up the duvet and said, I think now is the time to, you know kind of be with her and I cuddled. I there I was in bed with her with three healthcare professionals … It was very comfortable to do that. And that was very intimate thing to be a part of or to share with somebody else. (Rebecca, aged 38, bereaved partner of bisexual woman who died of cancer)

Service level

Service-level facilitators of good care included LGBT visibility, for example, health-care institutions partnering with LGBT organisations to communicate a visible message of acceptance and support. One participant described the positive experience she had when choosing a care home for her partner, reinforced by clear LGBT visibility within the institution:

She also got the company to get the OLGA- Older Lesbian and Gay something or other, which I’d never heard of … As a logo on the back of their brochure … So as to say, ‘We’re gay-friendly’, sort of thing … I think that, just having that as a sort of logo is a signal, isn’t it? You know, it’s a bit like, if you’re looking at hotels, you can google ‘gay-friendly hotels’, for example. (Trisha, aged 60, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of a neurological condition)

Knowledge of local LGBT friendly support services was also recognised as important, enabling professionals to signpost individuals towards support in line with their preferences for disclosure and LGBT community engagement. Participants described the critical importance of clarity from the care institution on its stance towards discrimination and how it would respond. Such clear messages empowered individuals to feel confident that they would be treated equitably and respectfully:

The world has changed so much … but I am sure there are still lesbians who are uncomfortable and not confident … and it’s about how do you reassure them that, it’s fine you are going to be treated the same, just be open because we’ve made sure that the professionals are going to have a problem with that … Um, and if you do have a problem, then this is who you talk to, to get it sorted. If you not brave enough to challenge someone, because not everybody is. (Pauline, aged 63, bereaved partner of bisexual woman who died of cancer)

Diverse preferences for disclosure and exploration of identity

Preferences regarding identity disclosure were diverse, shaped by interviewees’ personal, and historical, experiences. Some participants admitted collusion with heteronormative assumptions to avoid potential negativity or a constant ‘risk assessment’ around disclosure:

Somebody of my age … my longer experience is one of … hiding my sexuality, and not acknowledging that in a formal way … so there is always at the back of your, well certainly at the back of my mind … there is always a concern that somebody will be negative about you. Make judgement about you … so you spend a lot of energy trying to work out at what point in the conversation do you actually acknowledge and do you state your sexuality … It is not usually about the individual per se, it is about the risk assessment around that. (Fiona, aged 53, bereaved partner of lesbian woman who died of cancer)

Others remained fearful how disclosure would influence care, reluctant to share identity, regardless of how the request was framed:

Every single time I see someone who is going to be delivering a service to me. I wonder whether I should pretend otherwise in case it affects the service I get. So yes, it does affect me. (David, aged 62, gay man living with a neurological condition)

Some were more circumspect, sharing only where they felt it was pertinent to their care:

If it’s pertinent to reveal, I will reveal, definitely … I don’t mind being asked directly as long as, if I detected it’s more personal curiosity I will use the ‘Mind your own business’ response, or err, ‘Why do you need to know?’. Is there’s a reason for why you need to know then you need to know. (John, aged 52, gay man living with HIV and lung disease)

Others had spent many years closeted, unable to share their identity. For them, disclosure was critical and affirming, central to ensuring that health-care professionals understood who they were and who mattered to them:

Well to be recognised that I’m gay, to be understood that I’m gay. And I’ve got feelings about being gay. I umm, I like to be accepted. (Keith, aged 68, gay man living with cancer)

Irrespective of identity, or preferences for disclosure, participants described the universal importance of recognising that everyone deserves person-centred care, aligned to their needs:

I don’t think your sexuality should be an issue at all within a healthcare setting, because humanity is so diverse. Whatever your personal thoughts, you’re in a profession to treat people. No matter what they are. Your prejudices should never come into it. If they do, then it’s time for a change of profession. (Neil, aged 54, gay intersex man living with renal failure)

Discussion

This was the first study which sought to explore in depth the health-care experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness, not limited to HIV/AIDS. We identified barriers to accessing care at multiple levels: internalised, interactional and service level. While basic clinical needs of LGB people are common to everyone facing advanced illness, for trans people, there are additional clinical considerations. LGBT people may also face further societal stressors, increased isolation and family estrangements and legal concerns, all contributing to additional stress at a time of increased vulnerability. We also identified facilitators to good care at a service and interactional level.

Previous theories, including Bronfenbrenner’s36 ecological systems theory, have considered how environmental factors may influence an individual’s development and experiences. The ecological systems theory considers how the groups and institutions with which an individual may come into contact directly (Microsystem) or indirectly (Exosystem), the culture (Macrosystem) and changes over time (Chronosystem) may influence that individual. Our data expand this with an additional dimension, highlighting invisible barriers, internalised by the individual, which result from multiple homophobic and/or transphobic experiences across all of the systems.

Over recent years, there has been significant legislative change supporting the rights of LGBT people37–39 across Europe and the United States. However, societal and attitudinal change remains behind legal reform, and globally, particularly across Africa and Asia, persecution remains common.40 Despite policy recommendations to improve health care for LGBT people,13–15 discrimination and inadequate care persist.22,41 Such practices reduce or delay access to health care at critical points, causing LGBT people to rely on their own health knowledge,42 rather than seeking professional care. This jeopardises the health of LGBT individuals, causing them to suffer unnecessarily.

Public health approaches are needed to meet the needs of LGBT people facing advanced illness, working with communities and local and national networks. Advanced illness and bereavement create social and psychological challenges,43 and LGBT individuals experience additional stressors.18,20 However, such challenges are amenable to public health strategies: health promotion to address delays in accessing care, public education, community engagement and partnerships with LGBT organisations. Such approaches increase societal support, positively impacting on social morbidities associated with bereavement by addressing the root causes of isolation and stigma.43

Alongside public health approaches, there is also a need to improve clinical care delivery and reduce the potential for anxiety and fear of discrimination at a time of extreme vulnerability. Ten simple, low-cost recommendations to improve care for LGBT people facing advanced illness have been generated from the interviews (see Table 2). These recommendations include service-level signifiers of inclusion, including partnerships with LGBT organisations, increased visibility of the LGBT community in materials and images and embedding education on LGBT needs and experiences into core training on discrimination and diversity. This must focus on not only skills in delivering person-centred care but also knowledge and attitudes, promoting cultural sensitivity and addressing sources of discrimination.19,28 Additionally, health-care professionals need to reflect on their own attitudes and behaviours. Simple changes to practice could markedly improve care experiences for LGBT people, including avoiding heterosexually framed, assumption-laden, questions; sensitivity in exploration of identity; careful exploration of intimate relationships; and explicit inclusion of partners or significant others.

Table 2.

Ten recommendations to improve care for LGBT people facing advanced illness.

| Individual level | Avoid using heterosexually framed or assumption-laden language |

| Demonstrate sensitivity in exploration of sexual orientation or gender history | |

| Respect individuals’ preferences regarding disclosure of sexual identity or gender history | |

| Carefully explore intimate relationships and significant others, including biological and chosen family (friends) | |

| Explicitly include partners and/or significant others in discussions | |

| Service/institutional level | Make clear statement of policies and procedures related to discrimination |

| Include content regarding LGBT communities in training on diversity and discrimination | |

| Increase LGBT visibility in materials (in written content and images) | |

| Provide explicit markers of inclusion (e.g. rainbow lanyards or pin badges) | |

| Initiate partnerships and/or engagement with LGBT community groups |

LGBT: lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans.

Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths. This was the first national study which sought to examine health inequalities through the experiences of LGBT people facing advanced illness. Recruitment nationally through media and community networks44 enabled us to reach individuals who may not have felt comfortable to share their identity with their health-care teams but wanted to participate in this research study. Although we failed to recruit within Northern Ireland, we were able to reach rural and urban locations across the United Kingdom, unlike many LGBT health-care studies that have focused on cities with strong LGBT communities. Through media recruitment, it was not necessary to rely on snowball sampling, which limits transferability of studies due to homogeneous samples. Our methods also enabled maximum variation sampling with a breadth of ages, LGBT identities and illnesses. Finally, working with LGBT charity partners (GMFA/HERO) throughout this study, we have ensured the project design, and outputs have remained grounded in the needs of the populations.

Our study did have some limitations. Despite focused attempts to promote the study with bisexual and trans networks, we had lower recruitment and did not achieve data saturation within these groups. We were also unable to recruit any trans men; however, many studies fail to recruit at all within the bisexual and trans communities. Additionally, despite promotion within Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) LGBT groups, the majority of our participants were White British (34/40).

Future research

Collaborative health-care research with LGBT communities is increasing; however, many aspects remain under-researched.45 There is a need for research focusing on person-centred outcomes of LGBT people facing advanced illness, and bereavement, to help clinicians proactively identify those with acute needs, inform service development and improve care experiences. Additionally, further research exploring how best to make reference to sexual orientation and gender history in clinical assessment would help manage communication concerns and inform training and development.

Conclusion

Discrimination experienced by LGBT people facing advanced illness is unjust and at odds with legislation. Focused efforts are needed to improve care experiences for LGBT people through public health strategies to address issues in accessing care, and training and education, to address deficits in care delivery, focusing on knowledge, skills and attitudes of health-care professionals. However, this study also identified 10 simple, low-cost recommendations for individuals, services and institutions, to improve care for LGBT people facing advanced illness. Finally, through working collaboratively with LGBT communities to promote visibility and partnership, we can enact a culture shift by increasing expectations for person-centred care and improving care delivery.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Recruitment maps were produced using ArcGIS v10.1 (ESRI). This work was supported by the Marie Curie Research Grants Scheme, grant MCCC-RP-14-A17159.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for the study was granted by the UK National Research Ethics Service (Committee: London – Camberwell St Giles 14/LO/1148), and all procedures followed were in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were given an information sheet about the study, a minimum of 24 h to consider participation and had an opportunity to ask questions.

Informed consent: All participants gave informed consent before the interview. Anonymity of respondents was protected by the use of pseudonyms for all names of people, places and institutions.

References

- 1. Cochran S, Bjorkenstam C, Mays V. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 years, 2001-2011. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dibble S, Roberts S, Nussey B. Comparing breast cancer risk between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. Womens Health Issues 2004; 14: 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown J, Tracy J. Lesbians and cancer: an overlooked health disparity. Cancer Causes Control 2008; 10: 1009–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. D’Souza G, Wiley D, Li X, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of anal cancer in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 48: 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Katz M, Hessol N, Buchbinder S, et al. Temporal trends of opportunistic infections and malignancies in homosexual men with AIDS. J Infect Dis 1994; 170: 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, et al. HIV prevalence risk behaviors health care use and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 915–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feldman J, Goldberg J. Transgender primary medical care. Int J Transgenderism 2007; 2007: 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark M, Landers S, Linde R, et al. The GLBT Health Access Project: a state-funded effort to improve access to care. Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 895–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stein G, Bonuck K. Physician-patient relationships among the lesbian and gay community. J Gay Lesb Med Assoc 2001; 5: 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chakraborty A, McManus S, Brugha T, et al. Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. Br J Psychiatry 2011; 198: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mayer K, Bradford J, Makadon H, et al. Sexual and gender minority health: what we know and what needs to be done. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCabe S, Hughes T, Bostwick W, et al. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction 2009; 104: 1333–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National End Of Life Care Programme. The route to success in end of life care – achieving quality in acute hospitals, 2010, http://www.leedspalliativecare.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/rts_acute___final_20100830.pdf

- 14. Department of Health DOH. Bereavement: a guide for transsexual, transgender people and their loved ones. London: Department of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Department of Health. Sexual orientation: a practical guide for the NHS. London: Department of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Care Quality Commission. A different ending: addressing inequalities in end of life care. London: CQC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Chidgey-Clark J. Needs, experiences, and preferences of sexual minorities for end-of-life care and palliative care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2012; 15: 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sabin J, Riskand R, Nosek B. Health care providers’ implicit and explicit attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 1831–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bristowe K, Marshall S, Harding R. The bereavement experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or trans* people who have lost a partner: a systematic review, thematic synthesis and modelling of the literature. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 730–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sinding C, Barnoff L, Grassau P. Homophobia and heterosexism in cancer care: the experiences of lesbians. Can J Nurs Res 2004; 36: 170–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elliott M, Kanouse D, Burkhart Q, et al. Sexual minorities in England have poorer health and worse health care experiences: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doka KE. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Elwert F, Christakis N. The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 2092–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Department of Trade and Industry. Final regulatory impact assessment: civil partnership act 2004. London: Department of Trade and Industry, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gender Identity Research and Education Society (GIRES), https://www.gires.org.uk/whatwedo.

- 27. The Lancet. Meeting the unique health-care needs of LGBTQ people. Lancet 2016; 387: 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Garrison N, Ibanez G. Attitudes of health care providers toward LGBT patients: the need for cultural sensitivity. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. The Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. The CTAC: what is advanced illness? ’s-Hertogenbosch: CTAC. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas K; Prognostic indicator guidance (PIG). The gold standards framework centre in end of life care CIC. 4th ed., 2011, http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/General%20Files/Prognostic%20Indicator%20Guidance%20October%202011.pdf

- 31. Gomes B, McCrone P, Hall S, et al. Variations in the quality and costs of end-of-life care, preferences and palliative outcomes for cancer patients by place of death: the QUALYCARE study. BMC Cancer 2010; 10: 400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Costantini M, Beccaro M, Merlo F; ISDOC Study Group. The last three months of life of Italian cancer patients. Methods, sample characteristics and response rate of the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer (ISDOC). Palliat Med 2005; 19: 628–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. Geneva: WHO, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32 item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development. In: Gauvain M, Cole M. (eds) Readings on the development of children. New York: W.H. Freeman, 1994, pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 37. European Union. Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. Brussels: European Union, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. The Equality Act. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents, 2010.

- 39. Constitution of the United States. Equality protection clause of the fourteenth amendment, 2015, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/equal_protection

- 40. Hunt J, Bristowe K, Chidyamatare S, et al. ‘They will be afraid to touch you’. LGBTI people and sex workers’ experiences of accessing healthcare in Zimbabwe: an in-depth qualitative study. BMJ Global Health, 2: e000168 DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Curie M. ‘Hiding who I am’: the reality of end of life care for LGBT people, 2016, https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/policy-publications/june-2016/reality-end-of-life-care-lgbt-people.pdf

- 42. Johnson M, Nemeth L. Addressing health disparities of lesbian and bisexual women: a grounded theory study. Womens Health Issues 2014; 24: 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Public Health England. Public health approaches to end of life care: a toolkit. London: Public Health England and The National Council for Palliative Care, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marie Curie BK Blog. Improving care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* people at the end of life, 2015, https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/blog/improving-care-for-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-trans-people-at-the-end-of-life/48689

- 45. Stall R, Matthews D, Friedman M, et al. The continuing development of health disparities research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 787–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]