Abstract

Objectives

Diagnosis with an HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer includes unique social issues. However, it is unknown how common these psychosocial issues are for patients and whether they continue after treatment.

Materials and Methods

Patients with pathologically confirmed HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer (HPV-OPC, n=48) were recruited from two medical centers. Participants completed a computer assisted self interview that explored their psychosocial experiences during and after treatment. We examined responses overall and by age.

Results

The majority of participants with confirmed HPV-OPC, reported being told that HPV could have (90%) or did cause (77%) their malignancy, but only 52% believed that HPV was the main cause of their OPC. Participants over 65 years were less likely than younger participants to report that their doctors told them their tumor was HPV-positive (50% vs 84%, p=0.03).

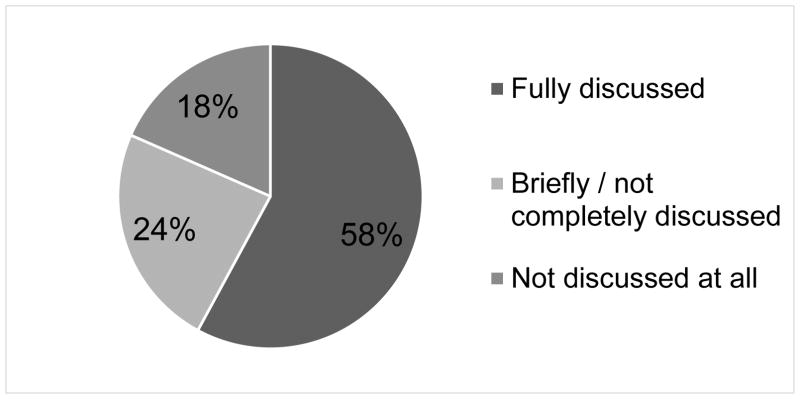

Anxiety that their tumor was HPV-related was a major issue among participants when first diagnosed (93%). However, only 17% still reported anxiety after treatment was complete. While many patients reported that providers discussed the emotional effects of diagnosis and treatment adequately (58%), almost half reported discussing these emotional effects inadequately (24%), or not at all (18%). Further, 18% reported that their families still wondered about some questions that they had never asked.

Conclusion

After treatment, some HPV-OPC patients remain concerned about HPV and have unanswered questions about HPV. Older patients had lower awareness of the role of HPV in their cancer.

Keywords: patient experience, OPC, anxiety, HPV

Introduction

Recognition that human papillomavirus (HPV) causes a growing subset of oropharyngeal cancers is a relatively recent phenomenon. While the psychosocial implications of diagnosis with HPV have been extensively studied in people with HPV-related cervical pre-malignancy and malignancy, analogous literature for head and neck cancer is lacking. A 2005 report by the Institute of Medicine highlighted the importance of examining psychosocial issues in head and neck cancer patients.[1] Building upon this recommendation, the National Cancer Institute Steering Committee Clinical Trial Planning Meeting in 2011[2] recognized the unique and important social issues raised by HPV-related head and neck cancers, and called for studies to help establish standards of care for this unique patient population.

Despite these calls to study this patient population, data on psychosocial issues among HPV-related head and neck cancer patients has been limited to descriptive qualitative studies with small sample sizes,[3,4] articles describing expert opinions,[1,5,6] or studies in head and neck cancer patients that do not consider HPV.[7,8] Nevertheless, the published studies to date suggest potential psychosocial issues at the time of diagnosis with HPV-OPC [4] that are specific to having a malignancy caused by a sexually transmitted infection. Whether psychosocial issues exist for many patients after treatment is unknown. With the growing prevalence of oropharynx cancer survivors[9,10], understanding their specific psychosocial needs emerges as an important consideration for both survivors and physicians.

Therefore, this study was designed to explore the psychosocial experiences of HPV-OPC survivors during and after treatment. Furthermore, we were interested in evaluating survivors’ understanding of HPV and OPC and their perceptions of provider communication regarding diagnosis of HPV-OPC.

Materials and methods

Study Design

This study included a one time survey assessment between September 2014 and February 2015 of 48 patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer (HPV-OPC) at either Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) or Johns Hopkins Head and Neck Surgery at Greater Baltimore Medical Center (GBMC), in Baltimore, Maryland. Patients with a prevalent diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancer were eligible. Participants at JHH included people diagnosed with HPV-OPC from 2009 to 2013 who were in follow-up as part of a different study[11] and were recruited to participate in this study (80% of those asked agreed). Participants approached for enrollment at GBMC were patients undergoing routine clinical surveillance (70% of patients approached agreed to participate).

Data Collection

Study participants completed a computer assisted self-interview (CASI). The survey included questions related to general knowledge of HPV-related OPC (e.g. “do you think HPV was the main cause of your cancer?”), and questions about their level of worry or anxiety. For example, patients were asked to rate their agreement with certain statements such as “when I was first diagnosed, I was anxious about the diagnosis of cancer” on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree). Using the same scale, they were also asked to rate their agreement with statements related to their relationships and sexual activity such as “since my doctor and I discussed the HPV status of my tumor, there has been significant tension between me and my partner or family members.”

Patients were also asked to describe the resources that were most helpful to them during and after treatment and about their experiences with their doctors after treatment (e.g. “now that you have completed therapy, do you feel that the long-term effects of cancer and treatment were explained to you?”). See Supplemental Table 1 for a copy of the survey instrument.

Data analysis

Medical record abstraction was performed to determine clinical characteristics and HPV tumor status, as available. Study population characteristics were described. Responses to the survey questions were compared by participants’ ages (≤55, 56–65, >65 years) and by years from cancer diagnosis (<2 years, 2–3 years, >3 years), using Fisher’s exact test. Level of agreement with survey questions was reported according to the scales used in those questions, including: 1) yes, no, don’t know; 2) strongly disagree/disagree, neutral, strongly agree/agree; 3) not at all, a little/somewhat, and very much.

All analysis used STATA version 14 (College Station, TX). While some analyses included all confirmed HPV- OPC cases, some questions were only asked to patients who remembered being told that their tumor was HPV-positive or those who finished cancer treatment, so analyses of these variables were restricted to these patient subsets.

Results

The study population comprised 48 participants diagnosed with HPV-OPC between 2009 and 2014 (Table 1). All participants were confirmed to have HPV-positive tumor testing in their medical records. The majority of participants were male (n=45, 94%), white (n=43, 90%), had never smoked tobacco (60%), and T3–T4 stage (56%). The median age at diagnosis was 60 years. Participants completed this survey a median of 3.0 years after diagnosis (range 0.1–5.6 years, interquartile range [IQR] =1.8, 3.9). At the time of the survey, 19% were currently undergoing treatment (n=9), and 81% had completed treatment (n=39).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer patients in Baltimore, MD, at diagnosis (N=48)

| Characteristic of interest | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 45 (94) |

| Female | 3 (6) |

| Race | |

| White | 43 (90) |

| Non-white | 5 (10) |

| Age in years: Median (Interquartile Range) | 60 (56, 64) |

| ≤ 55 | 12 (25) |

| 56–65 | 26 (54) |

| ≥ 66 | 10 (21) |

| Education^ | |

| High school or less | 6 (27) |

| College or advanced degree | 16 (73) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 42 (88) |

| Divorced/widowed/separated/single | 6 (12) |

| Smoking history | |

| Never smoker | 29 (60) |

| Ever smoker | 19 (40) |

| Alcohol history | |

| Never regular use | 5 (10) |

| Ever regular use | 21 (44) |

| Unknown | 22 (46) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Base of Tongue | 21 (47) |

| Tonsil | 22 (49) |

| Oropharynx NOS | 5 (4) |

| Tumor stage | |

| T0–T2 | 21 (44) |

| T3–T4 | 27 (56) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 2009–10 | 12 (25) |

| 2011–12 | 22 (46) |

| 2013–14 | 14 (29) |

| Years from diagnosis: median (Interquartile Range) | 3 (2, 4) |

| Timing of survey | |

| During treatment | 9 (19) |

| After treatment | 39 (81) |

Only available in a subset of participants who completed a survey for another study where they self-reported this information.

The majority (n=43, 90%) of participants reported being told that HPV could have caused their cancer, including 84% ever smokers and 93% of never smokers (Table 2). However, only 77% reported that their doctors actually told them that their tumor was HPV-positive, and only 52% thought that the main cause of their cancer was HPV. This included 32% of ever smokers and 66% of never smokers who thought that HPV was the main cause of their cancer. This proportion appeared to differ across age groups (Table 2), with older participants (>65 years) more likely than younger participants ( 65 years) to report not knowing whether HPV was the cause of their cancer (70% vs. 32%, p=0.07), and less likely to report that their doctors told them their tumor was HPV-positive (50% vs 84%, p=0.03).

Table 2.

Knowledge of HPV tumor status, by participant age, as reported at the time participants took the study survey.

| N (%)

|

%

|

p-value † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ≤55 N=12 |

56–65 N=26 |

>65 N=10 |

||

| Were you told HPV could have caused your cancer? | |||||

| Yes | 43 (90%) | 100% | 88% | 80% | |

| No | 3 (6%) | 0% | 8% | 10% | 0.57 |

| Don’t know | 2 (4%) | 0% | 4% | 10% | |

| Were you told by your doctors that your tumor was HPV positive? | |||||

| Yes | 37 (77%) | 92% | 81% | 50% | |

| No | 7 (15%) | 8% | 8% | 40% | 0.09 |

| Don’t know | 4 (8%) | 0% | 12% | 10% | |

| Do you think HPV was the main cause of your cancer? | |||||

| Yes | 25 (52%) | 58% | 62% | 20% | |

| No | 4 (8%) | 0% | 12% | 10% | 0.10 |

| Don’t know | 19 (40%) | 42% | 27% | 70% | |

| Do you think that the discussion of your tumor being HPV-positive could have been handled better by your health care providers? * | |||||

| Yes | 2 (5%) | 0% | 10% | 0% | |

| No | 34 (92%) | 100% | 86% | 100% | 0.80 |

| Don’t know | 1 (3%) | 0% | 5% | 0% | |

| Of the HPV related information you were told at diagnosis, what was the most helpful to you? ^ | |||||

| Cure/Survival Rate/Treatment Information | 18 (55%) | 60% | 47% | 75% | 0.43 |

| Acquisition/Transmission of HPV | 6 (18%) | 10% | 26% | 0% | |

| HPV is common/Information about HPV | 5 (15%) | 30% | 11% | 0% | |

| HPV is the cause of cancer | 4 (12%) | 0% | 16% | 25% | |

P-value from the Fisher’s exact test

Among 37 patients who remember being told their tumor was HPV-positive

Among 33 patients who remember being told their tumor was HPV-positive and answered this question

Among those finished cancer treatment, approximately half (n=22, 58%) reported that their providers discussed the emotional effects of diagnosis and treatment. Another 24% (n=9) of patients said these emotional effects were briefly but not completely discussed, and 18% (n=7) reported that no one discussed the emotional effects of cancer with them (Figure 1). When asked if family members had remaining (unanswered) questions about cancer, 18% (n=7) reported that their families still wondered about some questions that they had never asked.

Figure 1.

Participant reflection on how much the emotional effects of HPV-OPC had been discussed with them, among 39 HPV-OPC cases who had finished therapy.

Experience, anxiety and beliefs of patients who recall being told their tumor was HPV-positive

Additional questions regarding participants’ experience discussing their HPV tumor status were asked of the 37 patients (77%) who reported that their doctor told them that their tumor was HPV-positive. The majority of participants believed their providers adequately discussed their tumor status (n=34, 92%, Table 2). Over half of those surveyed reported the most useful HPV-related information at diagnosis was learning about rates of cure, survival, and treatment (n=18, 55%). Among all age groups, this was rated as the most helpful HPV-related information providers discussed (Table 2). Other information learned at diagnosis that was reported to be helpful by more than 10% of patients included information on: acquisition and transmission of HPV (18%), how common HPV is (15%), and that HPV was the cause of their cancer (12%).

Next, the survey evaluated anxiety and beliefs related to the knowledge that HPV was responsible for the survivor’s cancer. Anxiety was a major issue among these participants. Nearly all participants reported that when first diagnosed they felt very anxious about the diagnosis of cancer (n=27, 93%, Table 3). Even after treatment was complete, 17% of cases reported strong feelings of anxiety that their tumor was HPV-positive. Several years after diagnosis some cases reported they continued to be very much worried by how (16%) and why (14%) they became infected with HPV, and whether they were still infected with HPV (19%, Table 3). Nearly half of cases (49%) remained “a little or somewhat” worried after treatment about their HPV-positive tumor status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responses to anxiety, relationship dynamics, and worry related questions among 37 patients who remember being told that their tumor was HPV positive

| N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Strongly disagree/disagree | Neutral | Strongly agree/agree | |

| I FELT/FEEL ANXIOUS ABOUT… | |||

| The diagnosis of cancer, when I was first diagnosed | 0% | 7% | 93% |

| My tumor being HPV-positive, now that my treatment is complete | 47% | 36% | 17% |

| THERE HAS BEEN SIGNIFICANT TENSION… | |||

| Between me and my partner or family members, since my doctor and I discussed the HPV status of my tumor | 92% | 3% | 5% |

|

| |||

| Not at all | A little/ somewhat | Very much | |

|

| |||

| I FEEL WORRIED ABOUT… | |||

| Transmitting HPV to my current partner | 57% | 35% | 8% |

| Transmitting HPV to other family members ^ | 83% | 14% | 3% |

| Transmitting HPV to future sexual partners ^ | 89% | 0% | 11% |

| How I became infected with HPV | 38% | 46% | 16% |

| Why I became infected with HPV | 38% | 49% | 14% |

| Whether I am still infected with HPV | 32% | 49% | 19% |

This excludes 2 patients who said transmission to family members was “not applicable” and 8 patients who said transmission to future sexual partners was “not applicable”

Most cases reported not worrying about transmission of HPV to their current partners (n=21, 57%), family members (n=29, 83%), or future sexual partners (n=25, 89%). However, a small proportion of survivors reported continuing to strongly worry about transmission of HPV to their current partner (n=3, 8%), family members (n=1, 3%), or future sexual partners (n=3, 11%), with many more survivors reporting intermediate levels of worry (Table 3).

Despite these worries, relationship dynamics seemed to remain largely intact, with only 2 survivors (5%) reporting tension with their partner or family members following the discussion of their HPV-positive tumor status with providers (Table 3). Nearly all patients (34 of 37, 92%) remained married or in a committed relationship after diagnosis, and 72% reported that sexual intimacy was not affected by their diagnosis of HPV-OPC. However, 10 cases (28%) did report decreased sexual activity after diagnosis. Patient experience, anxiety and beliefs did not vary by time since diagnosis (results not shown).

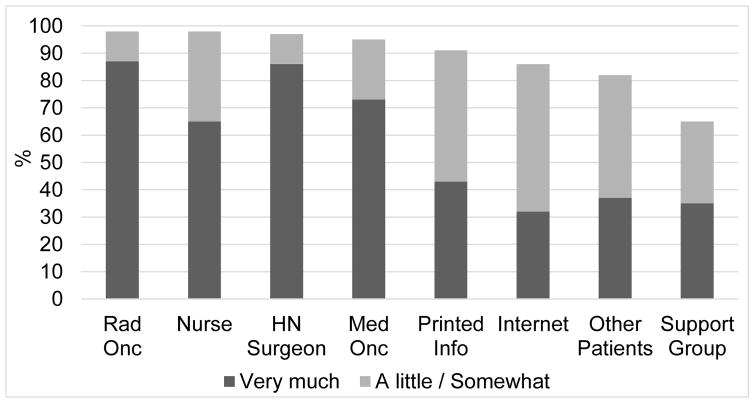

Perceived helpfulness of resources during and after therapy

We next explored which resources survivors viewed as helpful during diagnosis and treatment. The majority of respondents reported that conversations with medical oncologists (73%), radiation oncologists (87%), head and neck surgeons (86%), and nurses (65%) were very helpful during therapy (Figure 2). In contrast, after cancer treatment, survivors did not report that many resources aided with the emotional effects of their diagnosis. Among 39 patients who completed cancer treatment, few patients reported that psychologists (n=2, 5%), social support (n=8, 21%), church/prayer (n=12, 31%), or patient support groups/other (n=6, 15%) helped them with the emotional effects of cancer. In contrast, most patients did report that family members (n=30, 77%) helped with the emotional effects of treatment. Twenty-one percent of patients (n=8) reported that they did not talk to anyone (including family members) about the emotional effects of their cancer.

Figure 2.

Patient perspectives on resources that they found “very much” helpful and “a little or somewhat” helpful during diagnosis and treatment (see Appendix 1 for a copy of the survey).^ Respondents reported how helpful each of the following were: conversations with radiation oncologist (Rad Onc), conversations with nurses (Nurse), conversations with head and neck surgeon (HN Surgeon), conversations with medical oncologist (Med Onc), printed information provided by the clinical team (Printed Info), information from the internet (Internet), conversations with other patients (Other Patients), and support groups (Support Group).

^ This excludes 3 patients who said the question was “not applicable”

Of the challenges inquired about during treatment, most participants reported commonly anticipated side effects including swallowing difficulty (n=41, 85%), dry mouth (n=40, 83%), and lack of taste (n=35, 74%). After completion of treatment, similar side effects persisted including common reports of dry mouth (n=30, 77%), lack of taste (n=26, 68%), and swallowing difficulty (n=27, 69%). Participants were also asked about post-treatment follow up care. Most patients reported they had received a treatment summary plan (n=26, 67%), in-person reviews of follow-up care (n=32, 82%), and discussed the long-term effects of cancer treatment with their providers (n=31, 79%).

Discussion

This study provides one of the first descriptions of the knowledge gaps and psychosocial issues that arise after diagnosis and treatment with HPV-OPC. While most patients knew that HPV could have caused their cancer, almost half did not think HPV was the main cause of their cancer. This was especially pronounced among ever smokers. While most never smokers (66%) were told that HPV was the cause, only 32% of ever smokers were told that HPV was the main cause of their tumor. Among older patients, these knowledge gaps were more pronounced, with many older patients being unsure of the role HPV had in their cancer.

The finding that only half of providers discussed the emotional aspects of HPV-OPC diagnosis with patients highlights an opportunity to improve patient-provider communication and provider education. Despite not all patients having (or remembering) such a discussion of the emotional effects of their diagnosis with their provider, survivors generally reported low or no anxiety after completing treatment. However, some patients continued to have high levels of anxiety about their diagnosis, concern about transmitting HPV, and unanswered questions about HPV. Improving providers’ awareness regarding patient anxiety, both at the time of diagnosis and years after treatment, may help them to address the emotional effects of diagnosis with malignancy, that are compounded with the added complication of the causal relationship with sexually transmitted infection.

Other opportunities for providers to improve patient experience may include treatment summary plans and discussion of long-term side effects. Treatment summaries are recommended by the IOM to improve survivor quality of care.[12] These summaries include characteristics of patients’ diagnoses and therapy, which is supported by research indicating that written as well as verbal summaries improve patient understanding.[13] However, even with treatment summaries, there is still the possibility that patients will forget they had been given this information (recall bias).

Our finding that some patients were unaware that their tumors were HPV-positive is consistent with a previous study which found only 25% of diagnosed HPV-OPC patients recognized HPV as the primary cause of their cancer.[3] There are several possible reasons why older patients may have been less likely to know that their tumor was HPV-positive. First, older patients are often more likely to bring a companion or child to medical appointments,[14] which might make providers less comfortable explaining the role of an sexually transmitted infection. Second, older patients have lower health literacy and may be less able understand and/or to recall information concerning their disease even if their providers do discuss it [13,15]. It is also possible that older patients were less likely to ask about the cause of their cancer, and some physicians may not feel that a discussion of HPV is as relevant to an older individual since HPV-OPC is more common in younger age-cohorts. However, approximately one-fourth of all HPV-OPC patients in the U.S. are 65 years or older when diagnosed.[16] We note that recall bias is possible; i.e., providers may have reported to patients that their tumor was HPV-related, but the patients did not recall this when they completed the survey. To better identify the source of this knowledge gap, future studies might consider collecting parallel data from patients and their providers.

We also found that anxiety and worry are major issues among HPV-OPC patients. Although survival is increased for patients with HPV-OPC compared to HPV-negative OPC, 17% of patients in our study reported feeling anxious that their tumor was HPV-positive after treatment was complete. The HPV-related issues patients reported to be of most concern were how they became infected with HPV, why they became infected with HPV, and whether they are still infected with HPV. These are domains of knowledge that can be addressed by multidisciplinary provider teams, and therefore represent additional opportunities for education.

This study had several strengths and limitations. Participants included a diverse sample of patients in terms of age and cancer stage. However, the sample size of the study was limited, and some participants did not remember being told their tumors were HPV-related so could not answer questions about their anxiety in having HPV-related cancer. The study population was primarily male and white, and results may not reflect the experience of female and minority patients.

Conclusions

This is the one of the first studies to explore the psychosocial experience of patients during and after diagnosis with HPV-OPC. Patients’ understanding of and anxiety about the role of HPV in their cancer was variable, with lower awareness among older patients. The fact that most patients reported their providers discussed the emotional aspects of their diagnosis with them highlights how provider care and communication around this infection-related head and neck cancer has improved over the past 15 years. However, other patients reported no or inadequate discussion, unanswered questions, and continuing anxiety, representing potential opportunities to improve survivor quality of life.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Most HPV-OPCs were told HPV could have (90%) or did cause (77%) their malignancy.

Participants >65 years were less likely to be told their tumor was HPV-positive.

Only 32% of ever smokers thought HPV was the main cause of their cancer.

However 66% of never smokers thought HPV was the main cause of their cancer.

After completing therapy, some participants (18%) still had unanswered questions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [grant number P50 DE019032]; and the Oral Cancer Foundation.

Role of the Funding Source

Funders had no role in the design or interpretation and presentation of the study.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adelstein DJ, Ridge JA, Brizel DM, Holsinger FC, Haughey BH, O’Sullivan B, et al. Transoral resection of pharyngeal cancer: summary of a National Cancer Institute Head and Neck Cancer Steering Committee Clinical Trials Planning Meeting, November 6–7, 2011, Arlington, Virginia. Head Neck. 2012;34:1681–703. doi: 10.1002/hed.23136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milbury K, Rosenthal DI, El-Naggar A, Badr H. An exploratory study of the informational and psychosocial needs of patients with human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncology. 2013;49:1067–71. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxi SS, Shuman AG, Corner GW, Shuk E, Sherman EJ, Elkin EB, et al. Sharing a diagnosis of HPV-related head and neck cancer: the emotions, the confusion, and what patients want to know. Head & Neck. 2013;35:1534–41. doi: 10.1002/hed.23182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold D. The psychosocial care needs of patients with HPV-related head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2012;45:879–97. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu A, Genden E, Posner M, Sikora A. A patient-centered approach to counseling patients with head and neck cancer undergoing human papillomavirus testing: a clinician’s guide. Oncologist. 2013;18:180–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, de Bree R, Keizer AL, Houffelaar T, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MH, et al. Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:e129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haman KL. Psychologic distress and head and neck cancer: part 1--review of the literature. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:155–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fakhry C, Andersen KK, Eisele DW, Gillison ML. Oropharyngeal cancer survivorship in Denmark, 1977–2012. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:982–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel MA, Blackford AL, Rettig EM, Richmon JD, Eisele DW, Fakhry C. Rising population of survivors of oral squamous cell cancer in the United States. Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cncr.29921.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rettig EM, Wentz A, Posner MR, Gross ND, Haddad RI, Gillison ML, et al. Prognostic Implication of Persistent Human Papillomavirus Type 16 DNA Detection in Oral Rinses for Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:907–15. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Health and Medicine Division; n.d. [accessed April 5, 2016]. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2005/From-Cancer-Patient-to-Cancer-Survivor-Lost-in-Transition.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparks L, Nussbaum JF. Health literacy and cancer communication with older adults. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71:345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene MG, Adelman RD. Physician-older patient communication about cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50:55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amalraj S, Starkweather C, Nguyen C, Naeim A. Health literacy, communication, and treatment decision-making in older cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2009;23:369–75. 165834 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, Xiao W, Westra WH, Trotti A, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.