Abstract

Action on the social determinants of health (SDH) is required to reduce inequities in health. This article summarises global progress, largely in terms of commitments and strategies. It is clear that there is widespread support for a SDH approach across the world, from global political commitment to within country action. Inequities in the conditions in which people are born, live, work and age, are however driven by inequities in power, money and resources. Political, economic and resource distribution decisions made outside the health sector need to consider health as an outcome across the social distribution as opposed to a focus solely on increasing productivity. A health in all policies approach can go some way to ensure this consideration, and we present evidence that some countries are taking this approach, however given entrenched inequalities, there is some way to go. Measuring progress on the SDH globally will be key to future development of successful policies and implementation plans, enabling the identification and sharing of best practice. WHO work to align measures with the sustainable development goals will help to forward progress measurement.

Keywords: public health

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Officials and academics will be aware of action on the social determinants of health in their territories or fields of interest.

However, there is no up-to-date summary of action across the world. This paper provides such an overview.

What are the new findings?

The paper provides a useful, high-level insight into action across the world.

It is clear that there has been sustained expansion of action on the social determinants of health and an increase in higher level restructuring to enable real action, with for instance an increase in health in all policies approaches within governments.

Recommendations for policy

The report will be helpful to those trying to make a case for change in their territories.

It provides a useful summary of action that can then be further investigated if of interest.

Further work is needed to determine the degree to which commitments in strategies are followed through, and measurement of change should be considered an important step in that process.

Introduction

The WHO Global Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) concluded that social injustice is killing on a grand scale. Specifically, the Commission identified inequities in the conditions in which people are born, live, work and age, driven by inequities in power, money and resources driving inequities in health.1 As of 2015, average life expectancy in Japan was 83.7 years and in Sierra Leone, just 50.1 years.2 There clearly remains a rationale for action to improve the lives of those living in poorer countries such as Chad. However, as has been well documented, inequalities are also evident within countries, towns and cities, for example, there is a 20-year gap in male life expectancy between the richest and poorest areas in Glasgow. The average life expectancy for men in India was 62 at the same time that it was 54 for men living in the poorest area of Glasgow—Calton.3 Similarly in Baltimore and Washington DC, those living in the poor part of the city have a life expectancy 20 years shorter than those in a rich part.3

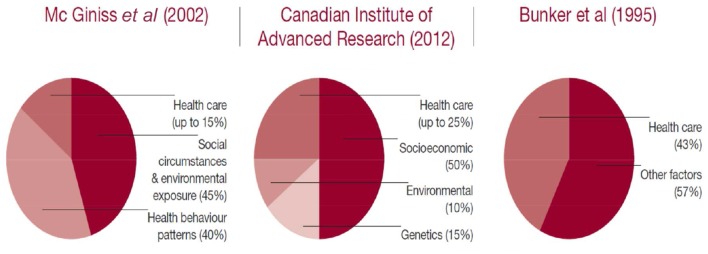

While there are competing views as to the scale of the influence of the social determinants of health (SDH), figure 1, complied by the Kings Fund, demonstrates that social and environmental influences are highly significant, contributing to between 45% and 60% of the variation in health status. Providing universal access to good healthcare is therefore necessary, but insufficient to optimise the health of populations and reduce inequities in health. In England, for example, there is free universal health coverage but widespread, large and persistent inequalities in health between social groups. This is largely because, for many communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), acting at the point at which someone presents with a health problem can be too late. To improve health, reduce health inequalities and reduce costs on healthcare (and other service) budgets, we need to improve the conditions in which people are born, live, work and age.

Figure 1.

Estimates of the contribution of the main drivers of health status.

Given persistent inequalities within and between countries and recognising the human and economic cost of inaction, the Lancet-University of Oslo Commission of Global Governance for Health called for global political solutions that go beyond the health sector alone, and beyond technical solutions and unilateral national action.4 In this paper, we develop and update our previous reporting of progress across the World, in 20105 and 2014.6

Global action towards health in all policies

Following the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health7 was adopted by 125 member states during the WHO World Conference on SDH on 21 October 2011. The declaration expresses global political commitment for the implementation of a SDH approach to reduce health inequities and to achieve other global priorities. The rationale was that it would help to build momentum within countries for the development of dedicated national action plans and strategies.8

In 2011, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly also adopted the Political Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases9 calling for the development of multisectoral approaches to health at all government levels and to address the underlying determinants of health.

In May 2012, the 65thWorld Health Association then endorsed the Rio declaration and its recommendations. It approved measures to support the five priority actions recommended in the declaration to address social determinants of health.10 This was followed by a UN Resolution on Global Health and Foreign Policy in December 2012 calling on member states and the UN to accelerate universal health coverage and implement broad public health measures addressing the SDH through cross-sectoral policies.11

The 2010 WHO Adelaide Statement on Health in All Policies (HiAP) paved the way for global recognition of the need for cross-sectoral action as well as considering health in wider policies in order to improve health outcomes and equity. HiAP is a policy strategy, which targets the key social determinants of health through integrated policy response across relevant policy areas with the ultimate goal of supporting health equity. HiAP is thus closely related to concepts such as ‘intersectoral action for health’, ‘healthy public policy’ and ‘whole-of-government approach’. The HiAP approach is being advocated in several countries and in June 2013 the WHO eighth Global Conference on Health Promotion was dedicated to HiAP,12 building momentum for its implementation and highlighting the need to strengthen skill and political capacity to address the SDH.

There have also been a number of recent and significant supporting global developments, with perhaps the most significant recent social policy development being the adoption of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the UN.13 There is a high level of commonality between the SDGs and the improvement of the SDH.14

Another important development is The Declaration of Oslo, 2015, passed by the General Medical Assembly in Moscow. It sets out the importance of social determinants of health and principles of action for World Medical Association, National Medical Associations and individual doctors.28 This declaration explicitly sets out a role for the WMA in advising doctors and other health professions of good and innovative examples that will have a positive impact on the social determinants of health. In doing so, it importantly sets out an advocacy and leadership role for doctors and health professionals to improve people’s lives through action initiated outside the health sector.

Europe buys in but economic policies could be more supportive

Health 2020 is the European health policy framework adopted by the 53 Member States of the WHO European region in September 2012. It aims to support action across government and society to: ’significantly improve the health and well-being of populations, reduce health inequalities, strengthen public health and ensure people-centred health systems that are universal, equitable, sustainable and of high quality'. In October 2010, WHO European Office launched a review of social determinants and the health divide in the region15 to support the Health 2020 strategy.

In 2015, the 53 member states of the region signed the Minsk agreement committing to the adoption of the life-course approach across the whole of government that would improve health and well-being, promote social justice and contribute to sustainable development and inclusive growth and wealth in all countries.

The European commission also administers the EU Health Programme Fund, which is the main instrument the EC uses to implement the EU Health Strategy. This has provided an important strand in the EU contribution to reduce health inequalities in Europe by cofunding projects and actions through successive Health Programmes since 2003. To date, a total of 64 actions, involving nearly 700 organisations and institutions from all EU, European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and European Economic Area (EEA) countries and some candidate countries, have been funded, with EC cofunding amounting to €40 million. The current, Third Health Programme 2014–20, is geared towards contributing to the objectives of the Europe 2020 strategy, and continues to address health inequalities as a priority.16

The European Parliament has recently allocated funds to develop pilot projects designed to test the feasibility and usefulness of action in the area of health inequalities.17 The European Pact for Mental Health and Well-being is another related EU policy initiated in 2008. It recognises that considerable inequalities in mental health status exist and seeks to address these. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has also been working with national partners to forward action on Social, Economic and Environmental Determinants of Health in the context of sustainable human development.18

National activities in a number of countries have followed the publication of Health 2020, with Lithuania producing a new national health plan and Serbia running an appraisal of cross-sectoral governance systems and capacity to address social inequalities. In 2013, France launched a national health strategy. This included a social contract under which every government department would be accountable for the impact of their policies on public health and health inequalities, with the aim of ensuring a strong focus on the social determinants of health inequalities.19 Eight member states requested support from WHO to integrate equity in the policy process and a further six-member states are working with WHO Regional Office for Europe to develop strategies to address the SDH and health equity with a particular focus on the Roma population. Sweden have recently appointed a commission on health inequalities to further inform their strategy, and Norway, Hungary and Poland have produced analytical reports.6

However, while many health departments have embraced the SDH rationale, they do not hold key levers for change. Social policy is often aligned with the SDH, however economic policies to promote growth may have done so at the expense of quality of work and security, austerity programmes have resulted in reduced services and cuts to the real value of social protection. More needs to be done to incentivise, or require, other sectors to consider health outcomes.

The EU treaty obliges all EU policies to adhere to the HiAP approach, although not all countries have yet integrated this into legislation. Given the current policy environment, integrating the HiAP approach with the requirement to adhere to the SDGs makes much sense. For example, in April 2016, the Welsh, ‘The Wellbeing of Future Generations’ Act came into effect. The Act requires that there is a commissioner, guidance and training material for a wide range of public bodies who will have legal obligation in a number of areas that codify the SDGs, including prevention. The overarching goals are to ensure Wales is: prosperous, resilient, equal, cohesive, healthy, culturally sensitive and globally responsive.

North America-Canada has led the way, the USA was switching focus to prevention under Obama

Canada has been at the forefront of research into the SDH, and this continues to be the case, with academics and practitioners advocating an SDH approach to public health and influencing policies.

Social determinants of health are now firmly on the agenda in Canada. There is a great deal of activity both at national and provincial level. The Federal Minister of Health has declared publicly that SDH is a priority for the government. Supporting the Federal Ministry, the Public Health Agency of Canada has a SDH team. Several Provinces have social determinants of health as central to their plans. The Canadian Medical Association has declared their commitment to action on SDH. In pursuing this goal, they held Town Hall meetings across the nation to engage public opinion.20 21

Policy initiatives in the USA created by various provisions of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Healthy People 2020 and the National Partnership for Action created an environment for the USA to address social determinants of health and health equity. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, established the nation’s first National Prevention Council with heads of 17 federal agencies representing multiple sectors that impact health (eg, education, transportation, justice, etc). The National Prevention Council developed the National Prevention Strategy, which seeks to improve health outcomes by moving the nation from a focus on sickness and disease to one based on prevention and wellness.

In addition, there are a number of delivery and payment reform initiatives within Medicaid to address the diverse needs of the population served through an increased focus on social determinants of health. For example, through the State Innovation Models Initiative (SIM), a number of states are engaged in multipayer delivery and payment reforms that include a focus on population health and recognise the role of social determinants. For example, Connecticut’s SIM plan seeks to promote an Advanced Medical Home model that will address the wide array of individuals’ needs, including environmental and socioeconomic factors that contribute to their ongoing health. Its plan also includes community health improvement efforts that will coordinate efforts across community organisations, providers, employers, consumers and local public health entities.22

Also in 2010, the Healthy People initiative, coordinated by the US Department of Health and Human Services, added social determinants of health topic area. This national initiative involves a network of governmental, private, non-profit and academic partners who work together to set priorities for national public health improvements.23

In 2011, the National Partnership for Action—the nation’s first roadmap for reducing racial and ethnic health disparities—was released by the US Department of Health and Human Services. A dual approach of public health, policy and research actions directed by federal agencies to reduce health disparities coupled with broad local and regional engagement in the implementation of public health strategies to reduce disparities is underway across the USA.

This article is being submitted in July 2017. The repeal of the Affordable Healthcare Act is ongoing, with current estimates suggesting that the present format would result in 22 million losing health cover. There is understandably concern regarding the impacts that this could have on health inequalities.

South America—strategies to address health inequity becoming more common, but widespread poverty still persists

The countries in this region are at different points along the epidemiological transition, with certain countries facing a disproportionate burden of infectious disease and maternal mortality, while others are progressively facing higher rates of NCDs.

Strategies to address health inequity and inequality are increasingly at the centre of global and regional action in the Americas. In South America, the Union of South American Nations’ Council of Ministers of Health identified SDH as one of the five priorities in its 2010–2015 Plan of Action. Mercosur created an Intergovernmental Commission on Health Promotion and Social Determinants of Health, and Pan American Health Organisation (PAHOs) Strategic Plan (2014−2019), ensured that SDH is an integral part of the Organisation’s 5-year plan.24 In 2016, PAHO commissioned a 2-year independent review to describe and analyse major drivers of health inequalities across the whole region, with particular focus on 14 partner countries. The Commission will make recommendations for action to improve equity and inequalities in health for international, national and local organisations. The recommendations and analyses will focus on social determinants, ethnicity, gender and human rights and will align with the SDGs.

Many countries in the region do already have a long-standing and strong focus on social medicine, health equity and human rights and HiAP. In 2006, Brazil undertook a National Commission on Social Determinants of Health,25 and in Argentina and Chile, policies and governance arrangements were created to promote social determinants in the ministries of health and at high levels of national government.

The SDGs are an important mechanism through which to take action on social determinants

North Africa and the Middle East—member states have agreed to action on the SDH

The WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) initiated a regional strategic direction to implement the Rio political declaration, which was agreed by representatives of member states at a regional workshop in Cairo in September 2012. The regional office also supported the creation of a national database for health equity in Iran and capacity building in Afghanistan, Iraq and Oman for collecting and analysing disaggregated equity data.

The report identified a number of key themes specifically relevant to the region which interact with and impact on the SDH, in particular issues of gender equity, the status and employment conditions of migrants, fast urbanisation and conflict all tend to hinder development, improvement of the SDH and equity.

Since the Commission on the SDH 2005–2008, a number of initiatives have taken place to improve the knowledge base in the region and to engage member countries in debate on the SDH. In particular, knowledge sharing between academic institutions and non-profit organisations, and the production of country-level studies is seen as the basis for advocacy and the engagement of governments in the issue. Provision of primary healthcare is also seen as an entry point to raise awareness of the SDH in political debate. EMRO therefore initiated a consultation with member states on focusing community and primary care on the SDH as well as running a pilot programme of intersectoral action aimed at tackling health inequalities in a number of countries. It also runs programmes covering literacy, training and income in 12 of the 22 member states in the region (Afghanistan, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen); consideration is being given to ways of implementing programmes evaluated in other countries—such as conditional cash transfers to women in Latin America—in the context of different gender relations in the region. Community-based initiatives run by EMRO cover a population of around 3.7 million across all countries in the region and cover basic development needs, healthy cities and healthy villages and women’s development.

At the 61 st session of the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Committee, 2015, member states agreed a plan to hold a regional consultation on reducing health inequities in EMR through actions on the social determinants. Twenty-two member states agreed to implement the components of a proposed framework on SDH and related actions with technical support from WHO.

Sub-Saharan Africa—action on SDH a WHO strategic priority for this region but more to be done

To address widening health inequities within and between countries in the WHO African Region, accelerating response to the determinants of health was identified as one of the six WHO Strategic Directions for achieving sustainable health development in the African Region between 2010 and 2015. The strategy presents several priority interventions for reducing inequities through action on social determinants of health aligned to the key recommendations of the CSDH.

In May 2013, the WHO Regional Office for Africa (AFRO) gathered stakeholders from 12 Eastern and Southern African countries to discuss how HiAP can be implemented at the national level in order to achieve health equity; AFRO is also supporting the documentation of intersectoral case studies in Angola, Congo and Mozambique.

The WHO’s Equity, Health, Health Policy and Human Development programme works with AFRO to support member states implementing programmes addressing the SDH through the development of policies enhancing health equity, gender equity, human rights and poverty reduction. It also aims to support regions and member states to achieve greater synergy between trade and health policy to maximise benefits for poor and vulnerable populations.

At the recent World Medical Association Council meeting in Livingstone (2017), there was a real commitment to setting up collaborative groups—and to sharing experience between countries. The President of Zambia has set up a ministry responsible for SDH and countries, for example, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa are also keen to forward work in this area.

Asia—strategic buy in through action on non communicable diseases, some good examples of action but patchy progress

The WHO Regional Office for South East Asia have conducted reviews to assess the experience of inter-sectoral policies and actions to inform the development of further initiatives. A number of countries within the region have demonstrated promising results to improving health and addressing health equity. A review of Action to Address the Social and Environmental Determinants of Health Inequity in Asia Pacific was undertaken by Asia Pacific HealthGAEN and published in 2011. This identified a number of examples of action across the Asia Pacific region.26

There are a number of more recent examples. Thailand has been one of the most successful countries in reducing child mortality. Alongside improvements in equitable access to healthcare, Thailand holds a particularly democratic national health assembly open to the public each year, with regional representatives participating in health policy development.

Bangladesh has also seen large improvements in health outcomes. Latest data for 2013 show that life expectancy at birth was 71, compared with India at 66. This success has been attributed to poverty reduction, an increase in health resources and effective community-based interventions. The contribution of the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee to this success has been recognised, specifically in terms of coordinating the activity of non-governmental organisations.

The WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region (WPRO), AP-HealthGaen and the Social Inequity Reduction Network in Thailand advocated for addressing determinants of health beyond health sectors and strengthening capacities for health equity analysis and health impact assessment. WPRO is also in the process of identifying suitable cases studies for the assessment of experiences of intersectoral policies and has supported Cambodia, Laos, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines to undertake work on addressing aspects of SDH, including equity analysis, gender, working with specific populations and intersectoral action.

Every year Pacific island ministerial meetings are run, including health ministries. Recently, they declared a non communicable diseases (NCD) crisis and are developing approaches to tackle the issue. In 2013, they adopted an SDH approach within the healthy islands framework, which has political leverage, as does the Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool (Urban HEART) framework for the area, which was developed by the WHO Centre for Health Development in Kobe, Japan, adapted to an island setting and piloted in Fiji in 2012.

Most countries in both the Western Pacific as well as South East Asia country have NCDs strategies and recently WHO focused its attention on supporting countries with SDH strategies and universal health systems. UCL IHE have recently completed a review of health inequalities and the SDH for Taiwan, which was launched by President Ma in November 2015.

In China, Healthy China 2030, puts health at the centre of the country’s entire policy-making machinery, making the need to include health in all policies an official government policy. Multisectoral collaboration and innovation play a key role in Healthy China. With over 20 departments drafting the 2030 plan, a vision has been set for a significantly expanded health industry, which would become a mainstay of the national economy and will be tasked with improving the quality and level of health service delivered across the country. A key component of Healthy China is the promotion of healthy lifestyles and physical fitness, including through the development of Healthy Cities, to ensure a greater focus on prevention rather than treatment. Through greater technological advances and improvements to the health insurance system, and prevention, China is aiming to achieve health equity by 2030.27

Australia—regional progress in some areas despite lack of national policy

Australia has been prioritising health inequities for a number of years, with a particular focus on aboriginal populations. A Commonwealth Government Senate Committee (a bipartisan committee) conducted an inquiry into Australia’s response to the CSDH. However, the change of government in 2013 has meant that health inequities, in particular the SDH approach has come off the political agenda, while major financial cuts to public sector spending have been implemented across the board.

However, despite the lack of engagement by the current national government, the federal system allows the states and territories to implement their own initiatives and a number of policies and programmes are ongoing, while cross-sectoral policies are being developed in various states.

For example, in South Australia, HiAP approach has been adopted in response to escalating healthcare costs driven by an ageing population and increasing incidence of chronic disease. Ilona Kickbusch proposed that South Australia adopt a HiAP approach and that this approach be applied to targets contained within South Australia’s Strategic Plan (SASP); the Government’s overarching vision for its State. The unique advantage of this proposal was the significant and strategic importance of SASP to all South Australian government agencies. SASP contains 98 targets under six objectives and there is strong alignment between the SASP objectives and the social determinants of health. Oversight for HiAP was placed under the auspices of the high-level committee (the Executive Committee of Cabinet) responsible for overseeing the implementation of SASP, reflecting the strategic importance of the work.29

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates, with examples from regions, that across the world, there is commitment and action at national and local level to improve the social determinants of health. We have also probably just touched the surface, it is impossible to document all action and commitment in one paper, and so readers should be aware that if an area or country is not mentioned, this does not mean that there is no action.

The paper has not investigated progress on improving the social determinants of health or reducing health inequalities. Further work is needed to ensure that these commitments are carried through and that policies from a number of sectors align to ensure that power, money and resources are sufficiently distributed to support the health of all.

This paper has not tracked progress on measurement of the SDH across the continents. WHO are progressing a set of indicators that capture the SDH and align with the SDGs. Some countries have sophisticated monitoring systems, while others are yet to register births and therefore do not have meaningful denominators by which to calculate rates. Measuring progress on the SDH globally will be key to future development of successful policies and implementation plans, enabling the identification and sharing of best practice.

A health in all policies approach has been followed in some countries and more should be done to encourage remaining countries to take a holistic cross-government approach to improve health.

bmjgh-2017-000603supp001.docx (22.4KB, docx)

bmjgh-2017-000603supp002.docx (14KB, docx)

bmjgh-2017-000603supp003.docx (697.7KB, docx)

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: The authors have all made a substantive contribution to this draft and have edited and viewed the final version.

Disclaimer: The author(s) is(are) staff member(s) of the World Health Organization. The author(s) alone is(are) responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the World Health Organization.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring health for the SDGs Annex B: tables of health statistics by country, WHO region and globally, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marmot M. The Health Gap: the challenge of an Unequal World. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ottersen OP. The political origins of health inequity: prospects for change. The Lancet- University of Oslo Commission on Global Governance for Health. The Lancet 2014;383:630–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, et al. Building of the global movement for health equity: from Santiago to Rio and beyond. Lancet 2012;379:181–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61506-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2014. Action on the Social Determinants of Health Worldwide 2008-2013. Proceedings of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health 1-3 April 2014 Italy:Rockefeller Bellagio Centre; [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation. Rio Political Declaration on the Social Determinants of Health. 2011. accessed 3 Jul 2017 http://www.who.int/sdhconference/declaration/Rio_political_declaration.pdf?ua=1

- 8. World Health Organisation. Rio Political Declaration on the Social Determinants of Health. 2011. http://www.who.int/sdhconference/declaration/en/ (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 9. UN General Assembly 66th Session Agenda Item 117 - Resolution 62/2. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organisation (2012). ‘65th World Health Assembly closes with new global health measures’. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2012/wha65_closes_20120526/en/ (accessed 3 Jul 2017). [PubMed]

- 11. United Nations General Assembly. 67th Session – Agenda item 123 Global Health and Foreign Policy. 2012. http://daccess-dds-y.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N12/630/51/PDF/N1263051.pdf?OpenElement

- 12. The 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion. Helsinki, Finland: 10–14 Jun 2013 http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/8gchp/background/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 13. UN Sustainable Development Goals. 17 goals to transform our world. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- 14. United Nations. Sustainable Development Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300 (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 15. World Health Organisation. Review of social determinants of health and the health divide across the European Region. 2014.

- 16. Consumers Health and Food Executive Agency. Action on health inequalities in the European Union, final version: The EU Health Programme’s contribution to fostering solidarity in health and reducing health inequalities in the European Union 2003–13. 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/chafea/documents/health/health-inequality-brochure_en.pdf (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 17. European Commission. Social Determinants and health inequalities: pilot projects funded by the European Parliament. http://ec.europa.eu/health/social_determinants/projects/ep_funded_projects_en.htm (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 18. UNDP. Addressing social, economic and environmental determinants of health and the health divide in the context of sustainable human development. 2017. http://www.eurasia.undp.org/content/rbec/en/home/library/hiv_aids/addressing-social-economic-environmental-determinants-of-health.html (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 19. Touraine M. Health inequalities and France’s national health strategy. Lancet 2014;383:1101–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60423-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canadian Medical Association. Health equity and the social determinants of health. https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/health-equity.aspx (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 21. Canadian Medical Association. Health equity and the social determinants of health: a role for the medical profession. 2017. https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/PD13-03-e.pdf (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 22. State of Connecticut. Connecticut Healthcare Innovation Plan, Executive Summary. http://www.healthreform.ct.gov/ohri/lib/ohri/sim/plan_documents/innovation_plan_executive_summary_v82.pdf (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 23. Koh HK, Piotrowski JJ, Kumanyika S, et al. Healthy people: a 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Educ Behav 2011;38:551–7. 10.1177/1090198111428646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marmot M, Filho A, Vega J, et al. Acción conrespecto a losdeterminantessociales de lasalud en lasAméricas. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2013;34. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Association. Social Determinants of Health – Brazil. 2017. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/countrywork/within/brazil/en/ (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 26. Asia Pacific – Global action for health equity network. An Asia Pacific spotlight on health inequity: Taking Action to Address the Social and Environmental Determinants of Health Inequity in Asia Pacific. http://www.wpro.who.int/topics/social_determinants_health/ehgAPHealthgaenreport.pdf (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

- 27. World Health Organization and National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Shanghai 2016. 2016. http://healthpromotion2016.org/en/contents/83/114.html (accessed 3 Jul 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2017-000603supp001.docx (22.4KB, docx)

bmjgh-2017-000603supp002.docx (14KB, docx)

bmjgh-2017-000603supp003.docx (697.7KB, docx)