Abstract

Background

Determine the effect of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline- adherent initiation of postoperative radiation therapy (PORT), and different time to PORT intervals, on overall survival (OS) in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

Methods

Reviewing the National Cancer Database (NCDB) from 2006–2014, patients with HNSCC undergoing surgery and PORT were identified. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates, Cox regression analysis, and propensity score matching were used to determine the effect of initiating PORT ≤ 6 weeks of surgery, and different time to PORT intervals, on survival.

Results

41,291 patients were included in the study. After adjusting for covariates, starting PORT > 6 weeks postoperatively was associated with decreased OS (adjusted Hazard Ratio [aHR] 1.13; 99% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–1.19). This finding remained in the propensity score-matched subset (HR 1.21; 99% CI 1.15–1.28). Relative to starting PORT 5 to ≤ 6 weeks postoperatively, initiating PORT earlier was not associated with improved survival (≤ 4 weeks: aHR 0.93; 99% CI 0.85–1.02, 4 to ≤ 5 weeks: aHR 0.92; 99% CI 0.84–1.01). Increasing duration of delays beyond 7 weeks were associated with progressive small survival decrements (aHR 1.09, 1.10, and 1.12 for 7 to ≤ 8 weeks, 8 to ≤ 10 weeks, and > 10 weeks).

Conclusions

Non-adherence to NCCN Guidelines for initiating PORT within 6 weeks of surgery is associated with decreased survival. There is no survival benefit to initiating PORT earlier within the recommended 6-week timeframe. Increasing durations of delays beyond 7 weeks are associated with small progressive survival decrements.

Keywords: quality of care, head and neck cancer, postoperative radiation therapy, NCCN Guidelines, National Cancer Database

Introduction

Guideline concordant treatment and timeliness of care are two indicators of quality care1–7. The only measure of timely care incorporated into National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the time interval between surgery and postoperative radiation therapy (PORT), for which the “preferred interval between resection and postoperative RT is ≤ 6 weeks”8. Delays in initiating adjuvant therapy, and care not adherent to NCCN Guidelines, are nevertheless common9–12.

The oncologic effect of NCCN Guideline-adherent care for timely adjuvant therapy remains uncertain13. Prior studies have shown inconsistent effects on locoregional recurrence and survival, with some finding benefit14–21 and others no influence10,11,22–26. Most of the studies finding benefit to earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy were conducted over 15 years ago. It has been argued that recent improvements in radiation technology such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), altered fractionation, and/or concurrent chemotherapy may mitigate against the risk associated with delays initiating PORT13, although no consensus exists.

The effect of different time to initiation of PORT intervals on oncologic outcomes is also unknown. Some have argued, based on tumor repopulation times and surgical effects on hypoxia, that initiation of adjuvant therapy should commence as soon as reasonably achievable27. Whether there is a benefit to starting PORT earlier, such as within 4 or 5 weeks of surgery, remains understudied. Conversely, the negative consequences of progressive delays beyond 6 weeks postoperatively are also unknown.

Given the uncertainty surrounding the effect of time to initiation of PORT for patients with HNSCC undergoing surgery and adjuvant therapy, we sought to answer the following questions: 1) Is NCCN Guideline-adherent care in which PORT is initiated within 6 weeks of surgery associated with improved overall survival? 2) Is there a survival benefit to earlier initiation of PORT? and 3) What effect does increasing duration of delays beyond 6 weeks in initiating PORT have on survival?

Methods

Data Source

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) is a hospital-based cancer registry that is a joint program of the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) and the American Cancer Society. The NCDB annually collects high-quality and internally-appraised cancer data from more than 1,500 CoC accredited hospitals in the United States (US). It captures approximately 70% of cancer diagnoses annually in the US, making it the world’s largest clinical cancer registry28.

Study Cohort

The Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review. The NCDB was reviewed from 2006–2014 for patients with upper aerodigestive tract HNSCC and no prior radiation undergoing curative intent surgery followed by postoperative radiation with or without chemotherapy. HNSCC diagnoses were filtered using International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd Edition topography codes for the oral cavity (including lip), oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx as well as histology codes for SCC or relevant variants (Supplementary Table 1). 58,722 patients were identified. The following patients were excluded: brachytherapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, radioisotopes, or unspecified modality (n=568 for all forms of excluded radiation therapy), induction chemotherapy (n=9,896), palliative therapy (n=437), unknown survival time (n=6,031), definitive surgery > 180 days after diagnosis (n=129), and initiation of PORT > 180 days after surgery (n=370).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was overall survival (OS), which was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis until the date of death or last follow-up. Tumor registrars report patient follow-up to the NCDB annually and CoC accreditation standards require an annual 90% follow-up rate for all living analytic patients29. Neither patterns of failure nor disease-specific survival are available in the NCDB.

Study Variables

Covariates included sociodemographics (age, gender, race, educational attainment, median household income), insurance type, severity of comorbidity, oncologic (tumor site, clinical and pathologic American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] stage), and treatment characteristics (surgical margins, number of lymph nodes removed, 30-day hospital readmission, time to PORT, radiation modality, radiation duration, radiation dose, administration of concurrent chemotherapy), treatment facility type, treatment at more than one facility, surgery and radiation at the same facility, and region of the United States. Categorical variables were grouped for analysis as previously described9.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the effect of NCCN Guideline-adherent care on OS, time to initiation of PORT was dichotomized into ≤ 6 weeks or > 6 weeks postoperatively. Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates of survival were used to examine unadjusted survival time distributions for patients who initiated PORT ≤ 6 weeks or > 6 weeks postoperatively; comparisons were performed using the log rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with OS and adjust for potential confounding variables. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using log minus log plots. Associations between covariates was investigated prior to modeling to address potential collinearity effects. Variables significant at an alpha level of 0.05 on univariable analysis with perceived clinical relevance were entered into the Cox multivariable regression model. For categorical variables with unknown or missing information, an unknown category was included throughout but omitted from presentation of the final multivariable analyses for clarity of presentation.

Propensity score-matching (PSM) was used to minimize the effect of confounding from nonrandomized treatment assignment30 and decrease bias between the cohorts that commenced adjuvant therapy within or greater than 6 weeks postoperatively. Individual scores based on the probability of starting PORT within 6 weeks of surgery were calculated via fitting of a logistic regression model. One-to-one PSM without replacement was performed using a caliper width set to 0.05 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score31,32. After PSM, the OS of patients who initiated PORT ≤ 6 weeks and > 6 weeks postoperatively was examined using Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival and compared using the log rank test. Unadjusted hazard ratios for the PSM cohort were determined using Cox regression modeling.

Given the biological and prognostic differences between carcinogen-mediated and HPV-related head and neck cancer33,34, a planned sub-set analysis of the entire data set was performed excluding patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal SCC. Collaborative Stage Site Specific Factor 10 codes 020–060 were used to exclude patients with high-risk HPV serotypes (n=3656)35. Because HPV status was not recorded until 201035, but many patients from 2006–2010 likely had HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC with HPV status coded as unknown, a second subset analysis excluding all patients with oropharyngeal SCC (n=17,158) was performed to minimize this potential source of bias.

To determine whether earlier time to initiation of PORT is beneficial in terms of survival, and whether increasing duration of delays beyond 6 weeks is associated with progressive decrements in survival, time to PORT was analyzed as a categorical variable. Patients were divided into groups based on time to initiation of PORT: ≤ 4 weeks, 4 to ≤ 5 weeks, 5 to ≤ 6 weeks, 6 to ≤ 7 weeks, 7 to ≤ 8 weeks, 8 to ≤ 10 weeks, and > 10 weeks (intervals non-inclusive of lower bound and inclusive of upper bound for each). Time to PORT was analyzed as a categorical variable instead of as a continuous variable due to easier clinical interpretation and application of the hazard ratios. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to adjust for confounders and to determine the effect of different time to PORT initiation intervals on OS.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY). All statistical tests were two-sided. Given the large sample size, statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.01 and measures of precision of point estimates are presented as 99% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Demographic, Clinicopathologic, and Treatment Characteristics

41,291 patients with HNSCC undergoing surgery and PORT from 2006–2014 were included in the study. The patient demographic, clinicopathologic, and treatment characteristics and their relationship to initiation of PORT within 6 weeks of surgery are presented in Table 1. There were numerous significant differences in the characteristics of the groups with and without timely postoperative radiation. Overall 44.7% of patients (n=18,642) initiated PORT within 6 weeks of surgery.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinicopathologic, and Treatment Characteristics

| Total Patients (n=41,291) |

Initiation of PORT ≤ 6 weeks (n=18,462) |

Initiation of PORT > 6 weeks (n=22,829) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | # (%) | # (%) | # (%) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| <50 | 8474 (20.5) | 3815 (20.7) | 4659 (20.4) | |

| 50–59 | 14569 (35.3) | 6323 (34.2) | 8246 (36.1) | |

| 60–69 | 11195 (27.1) | 4977 (27.0) | 6218 (27.2) | |

| ≥ 70 | 7053 (17.1) | 3347 (18.1) | 3706 (16.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 31194 (75.5) | 14378 (77.9) | 16816 (73.7) | |

| Female | 10097 (24.5) | 4084 (22.1) | 6013 (26.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| White | 36234 (87.8) | 16608 (90.0) | 19626 (86.0) | |

| Black | 3556 (8.6) | 1279 (6.9) | 2277 (10.0) | |

| Other/Unknown | 1501 (3.6) | 575 (3.1) | 926 (4.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Insurance Type | <0.001 | |||

| Private | 20292 (49.1) | 9971 (54.0) | 10321 (45.2) | |

| Medicare | 13231 (32.0) | 5884 (31.9) | 7347 (32.2) | |

| Medicaid | 4056 (9.8) | 1240 (6.7) | 2816 (12.3) | |

| Uninsured | 2236 (5.4) | 780 (4.2) | 1456 (6.4) | |

| Other/Unknown | 1476 (3.6) | 587 (3.1) | 889 (2.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Highest Quartile | 9153 (22.2) | 4565 (24.7) | 4588 (20.1) | |

| 2nd Highest Quartile | 13607 (33.0) | 6136 (33.2) | 7471 (32.7) | |

| 2nd Lowest Quartile | 11096 (26.9) | 4812 (26.1) | 6284 (27.5) | |

| Lowest Quartile | 7022 (17.0) | 2787 (15.1) | 4235 (18.6) | |

| Unknown | 413 (1.0) | 162 (0.9) | 251 (1.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Median Household Income | <0.001 | |||

| Highest Quartile | 11958 (29.0) | 5667 (30.7) | 6291 (27.6) | |

| 2nd Highest Quartile | 11069 (26.8) | 5023 (27.2) | 6046 (26.5) | |

| 2nd Lowest Quartile | 10235 (24.8) | 4511 (24.4) | 5724 (25.1) | |

| Lowest Quartile | 7589 (18.4) | 3087 (16.7) | 4502 (19.7) | |

| Unknown | 440 (1.1) | 174 (0.9) | 266 (1.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 32726 (79.3) | 14974 (81.1) | 17752 (77.8) | |

| 1 | 6788 (16.4) | 2794 (15.1) | 3994 (17.5) | |

| ≥2 | 1777 (4.3) | 694 (3.8) | 1083 (4.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Cancer Primary Site | <0.001 | |||

| Oral Cavity | 13007 (31.5) | 3754 (20.3) | 9253 (40.5) | |

| Oropharynx | 17158 (41.6) | 8866 (48.0) | 8292 (35.3) | |

| Hypopharynx | 1093 (2.6) | 397 (2.2) | 696 (3.0) | |

| Larynx | 10033 (24.3) | 5445 (29.5) | 4588 (20.1) | |

|

| ||||

| AJCC Clinical Stage Grouping | <0.001 | |||

| I | 5387 (13.0) | 3304 (17.9) | 2083 (9.1) | |

| II | 5029 (12.2) | 2336 (12.7) | 2693 (11.8) | |

| III | 6700 (16.2) | 2958 (16.0) | 3742 (16.4) | |

| IV | 15531(37.6) | 6127 (33.2) | 9404 (41.2) | |

| Unknown | 8644(20.9) | 3737 (20.2) | 4907 (21.5) | |

|

| ||||

| AJCC Pathologic Stage Grouping | <0.001 | |||

| I | 2766 (6.7) | 1621 (8.8) | 1145 (5.0) | |

| II | 2922 (7.1) | 1281 (6.9) | 1641 (7.2) | |

| III | 5483 (13.3) | 2277 (12.3) | 3206 (14.0) | |

| IV | 18083 (43.8) | 6388 (34.6) | 11695 (51.2) | |

| Unknown | 12037 (29.2) | 6895 (37.3) | 5142 (22.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgical Margins | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 24470 (59.3) | 9461 (51.2) | 15009 (65.7) | |

| Positive | 10362 (25.1) | 4991 (27.0) | 5371 (23.5) | |

| Unknown | 6459 (15.6) | 4010 (21.7) | 2449 (10.7) | |

|

| ||||

| # of Lymph Nodes Removed | <0.001 | |||

| <18 | 7001 (17.0) | 3050 (16.5) | 3951 (17.3) | |

| ≥18 | 17714 (42.9) | 5620 (30.4) | 12094 (53.0) | |

| Unknown | 16576 (40.1) | 9792 (53.0) | 6784 (29.7) | |

|

| ||||

| 30-Day Hospital Readmission | <0.001 | |||

| None | 37027 (89.7) | 16785 (90.9) | 20242 (88.7) | |

| Unplanned | 1196 (2.9) | 420 (2.3) | 776 (3.4) | |

| Planned | 1129 (2.7) | 483 (2.6) | 646 (2.8) | |

| Unknown | 1939 (4.7) | 774 (4.2) | 1165 (5.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Radiation Modality* | <0.001 | |||

| External Beam | 18301 (44.3) | 8657 (46.9) | 9644 (42.2) | |

| IMRT | 21426 (51.9) | 8972 (48.6) | 12454 (54.6) | |

| 3DCT | 1511 (3.7) | 825 (4.5) | 686 (3.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Concurrent Chemoradiation | .701 | |||

| No | 19035 (46.1) | 8487 (46.0) | 10548 (46.2) | |

| Yes | 21876 (53.0) | 9798 (53.1) | 12078 (52.9) | |

| Unknown | 380 (0.9) | 177 (1.0) | 203 (0.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Radiation Dose (Gy) | <0.001 | |||

| < 40 | 2120 (5.1) | 769 (4.2) | 1351 (5.9) | |

| 40–59.9 | 10915 (26.4) | 4568 (24.7) | 6347 (27.8) | |

| 60–66 | 16780 (40.6) | 7094 (38.4) | 9686 (42.4) | |

| >66 | 8270 (20.0) | 4618 (25.0) | 3652 (16.0) | |

| Unknown | 3206 (7.8) | 1413 (7.7) | 1793 (7.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Radiation Treatment Duration (Days) | <0.001 | |||

| 1–35 | 2528 (6.1) | 766 (4.1) | 1762 (7.7) | |

| 36–42 | 5261 (12.7) | 2471 (13.4) | 2790 (12.2) | |

| 43–49 | 15179 (36.8) | 6686 (36.2) | 8493 (37.2) | |

| 50–63 | 14220 (34.4) | 6765 (36.6) | 7455 (32.7) | |

| ≥ 64 | 4103 (9.9) | 1774 (9.6) | 2329 (10.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Treatment Facility Type | <0.001 | |||

| Community | 3571 (8.6) | 1855 (10.0) | 716 (7.5) | |

| Comprehensive Community | 14561 (35.3) | 7372 (39.9) | 7189 (31.5) | |

| Academic | 17842 (43.2) | 6281 (36.9) | 11021 (48.3) | |

| Integrated Network | 4078 (9.9) | 1853 (10.0) | 2225 (9.7) | |

| Other/Unknown | 1239 (3.0) | 561 (3.0) | 678 (3.0) | |

|

| ||||

| # of Treatment Facilities | <0.001 | |||

| 1 CoC Facility | 8974 (21.7) | 4099 (22.2) | 4875 (21.4) | |

| > 1 CoC Facility | 9970 (24.1) | 4108 (22.3) | 5862 (25.7) | |

| Unknown | 22347 (54.1) | 10255 (55.5) | 12092 (53.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgery and Radiation at Same Facility | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 20317 (49.2) | 9693 (52.5) | 10624 (46.5) | |

| No | 20974 (50.8) | 8769 (47.5) | 12205 (53.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Region of United States | <0.001 | |||

| East | 7838 (19.0) | 3102 (16.8) | 4736 (20.7) | |

| Central | 11912 (28.8) | 5660 (30.7) | 6252 (27.4) | |

| South | 14340 (34.7) | 6551 (35.5) | 7789 (34.1) | |

| West | 5962 (14.4) | 2588 (14.0) | 3374 (14.8) | |

| Unknown | 1239 (3.0) | 561 (3.0) | 678 (3.0) | |

Abbreviations: PORT = postoperative radiation therapy, AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer, IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy, 3DCT = 3D Conformal Therapy, Gy = Gray, CoC = Commission on Cancer

Certain rows/columns may not sum to the total in cases where one of the categorical variables has a cell size < 10 to protect patient identity per NCDB policy.

Effect of Initiating PORT ≤ 6 Weeks Postoperatively on Survival

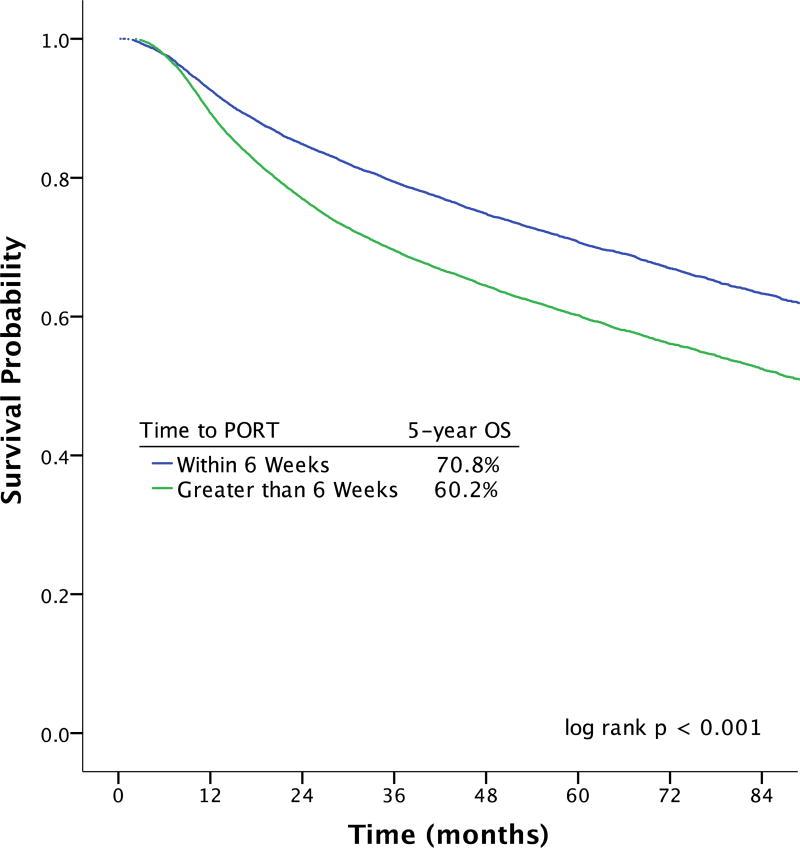

Initiating adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks postoperatively was associated with a 10% absolute decrease in 5-year OS on unadjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates relative to initiating adjuvant radiation within 6 weeks of surgery (60.2% vs 70.8%; log rank p < 0.001) (Figure 1). The results of the univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis are shown in Table 2. On univariable analysis, starting adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery was associated with a 50% relative increase in mortality (HR 1.48; 99% CI 1.41–1.55). After adjusting for relevant covariates, commencing adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery remained associated with decreased OS (aHR 1.13; 99% CI 1.08–1.19).

Figure 1.

| Months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # at Risk | 0 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 | 84 |

| PORT ≤ 6 weeks | 18462 | 16438 | 13517 | 10527 | 8017 | 5772 | 3878 | 2453 |

| PORT > 6 weeks | 22829 | 19727 | 15035 | 11152 | 8242 | 5816 | 3801 | 2313 |

Table 2.

Effect of Initiating PORT Within 6 Weeks of Surgery on Overall Survival: Univariable and Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Models

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Patient Variable | Hazard Ratio (99% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (99% CI) |

|

| ||

| Initiation of PORT > 6 Weeks | 1.48 (1.41–1.55) | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) |

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| <50 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 50–59 | 1.23 (1.15–1.32) | 1.21 (1.12–1.30) |

| 60–69 | 1.62 (1.51–1.74) | 1.37 (1.26–1.48) |

| ≥ 70 | 2.67 (2.48–2.87) | 1.99 (1.82–2.18) |

|

| ||

| Female Gender | 1.17 (1.11–1.23) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Black | 1.44 (1.34–1.55) | 1.11 (1.02–1.19) |

| Other | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) |

|

| ||

| Insurance Type | ||

| Private | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Medicare | 2.39 (2.27–2.52) | 1.62 (1.50–1.75) |

| Medicaid | 2.32 (2.16–2.50) | 1.47 (1.38–1.57) |

| Uninsured | 1.79 (1.62–1.98) | 1.40 (1.20–1.64) |

| Other | 1.76 (1.50–2.05) | 1.32 (1.10–1.60) |

|

| ||

| Education | ____a | |

| Highest Quartile | 1 (Ref) | |

| 2nd Highest Quartile | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | |

| 2nd Lowest Quartile | 1.37 (1.29–1.47) | |

| Lowest Quartile | 1.53 (1.42–1.65) | |

|

| ||

| Median Household Income | ||

| Highest Quartile | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 2nd Highest Quartile | 1.24 (1.16–1.32) | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) |

| 2nd Lowest Quartile | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | 1.15 (1.07–1.22) |

| Lowest Quartile | 1.62 (1.51–1.73) | 1.24 (1.15–1.32) |

|

| ||

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 1 | 1.50 (1.42–1.59) | 1.21 (1.14–1.28) |

| ≥2 | 2.26 (2.07–2.46) | 1.70 (1.56–1.86) |

|

| ||

| Cancer Primary Site | ||

| Oral Cavity | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| Oropharynx | 0.33 (0.31–0.34) | 0.37 (0.35–0.40) |

| Hypopharynx | 1.22 (1.09–1.36) | 1.02 (0.91–1.14) |

| Larynx | 0.71 (0.67–0.74) | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) |

|

| ||

| AJCC Clinical Stage Grouping | ____a | |

| I | 1 (Ref) | |

| II | 1.55 (1.41–1.70) | |

| III | 1.41 (1.29–1.54) | |

| IV | 1.69 (1.56–1.83) | |

|

| ||

| AJCC Pathologic Stage Grouping | ||

| I | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| II | 1.33 (1.17–1.52) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) |

| III | 1.29 (1.15–1.46) | 1.44 (1.27–1.62) |

| IV | 1.87 (1.68–2.08) | 1.93 (1.73–2.15) |

|

| ||

| Positive Surgical Margins | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | ____a |

|

| ||

| ≥ 18 Lymph Nodes Removed | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | ____a |

|

| ||

| 30-Day Hospital Readmission | ||

| None | 1 (Ref) | ____a |

| Unplanned | 1.40 (1.24–1.58) | |

| Planned | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | |

|

| ||

| Radiation Modality | ||

| External Beam | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| IMRT | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) |

| 3DCT | 1.38 (1.23–1.56) | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) |

|

| ||

| Concurrent Chemoradiation | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 1.20 (1.14–1.26) |

|

| ||

| Radiation Dose (Gy) | ||

| 60–66 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| < 40 | 2.20 (2.02–2.40) | 1.66 (1.51–1.82) |

| 40–59.9 | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | 1.14 (1.07–1.20) |

| >66 | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) |

|

| ||

| Radiation Treatment Duration (Days) | ||

| 43–49 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| 1–35 | 2.33 (2.15–2.53) | 1.72 (1.57–1.89) |

| 36–42 | 0.91 (0.84–0.99) | 0.93 (0.86–1.01) |

| 50–63 | 1.13 (1.07–1.19) | 1.19 (1.13–1.26) |

| >64 | 1.59 (1.48–0.1.71) | 1.46 (1.35–1.58) |

|

| ||

| Treatment Facility Type | ____a | |

| Community | 1 (Ref) | |

| Comprehensive Community | 0.95 (0.87–1.03) | |

| Academic | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | |

| Integrated Network | 1.04 (0.93–1.15) | |

|

| ||

| Treatment at >1 CoC Facility | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | ____a |

|

| ||

| Surgery and PORT at Different Facilities | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | ____a |

|

| ||

| Region of United States | ____a | |

| East | 1 (Ref) | |

| Central | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | |

| South | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) | |

| West | 0.93 (0.86–1.01) | |

Abbreviations: PORT = postoperative radiation therapy, CI = confidence interval. Ref = reference, AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer, IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy, 3DCT = 3D Conformal Therapy, Gy = Gray, CoC = Commission on Cancer.

Dropped out of final multivariable model

Effect of Initiating PORT ≤ 6 Weeks Postoperatively on Survival in the Propensity Score-Matched Cohort

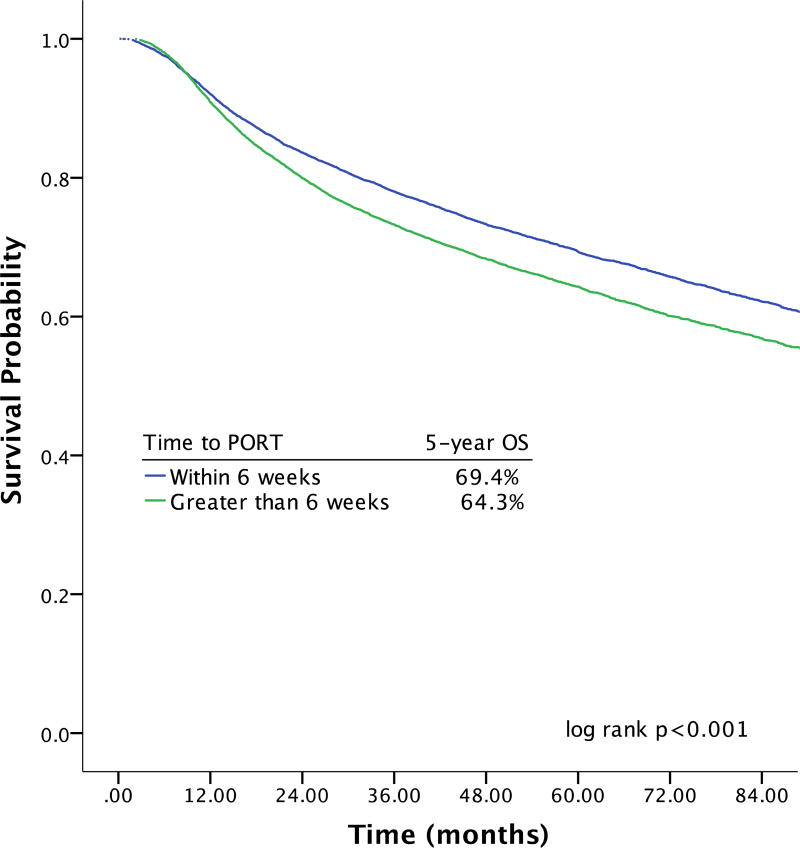

Because of the inherent imbalances in characteristics between the groups that did and did not start adjuvant therapy within 6 weeks of surgery9, a propensity score-adjusted subset analysis was performed based on the likelihood of initiating PORT within 6 weeks of surgery (Supplementary Table 2). In the propensity score-matched cohort of 29,910 patients, initiating adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery was associated with a 5% absolute decrease in 5-year OS relative to initiating adjuvant therapy within 6 weeks of surgery (64.3% vs 69.4%; log rank p < 0.001) (Figure 2). From univariable analyses, initiation of adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery was associated with a 20% relative increased risk of mortality (HR 1.21; 99% CI 1.15–1.28).

Figure 2.

| Months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # at Risk | 0 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 | 84 |

| PORT ≤ 6 weeks | 14951 | 13207 | 10732 | 8263 | 6229 | 4481 | 3000 | 1895 |

| PORT > 6 weeks | 14951 | 13151 | 10292 | 7789 | 5815 | 4161 | 2732 | 1677 |

Subset Analysis Excluding High-Risk HPV-Related SCC and Oropharyngeal SCC

Given the large survival difference in oropharynx cancer patients in this study and the known biological and prognostic differences between carcinogen-mediated and HPV-related HNSCC33,34, a subset analysis of the entire dataset was performed excluding patients with high-risk HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma. After excluding patients with high-risk HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma and adjusting for relevant covariates, starting adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery remained associated with an increased risk of death (aHR 1.13 99% CI 1.08–1.19, Supplementary Table 3). In a second subset analysis of the entire dataset excluding all oropharyngeal SCC patients, the risk of mortality for initiating PORT more than 6 weeks after surgery was unchanged on multivariable analysis (aHR 1.09; 99% CI 1.03–1.15, Supplementary Table 4).

Effect of Increasing Time to Initiation of PORT on Survival

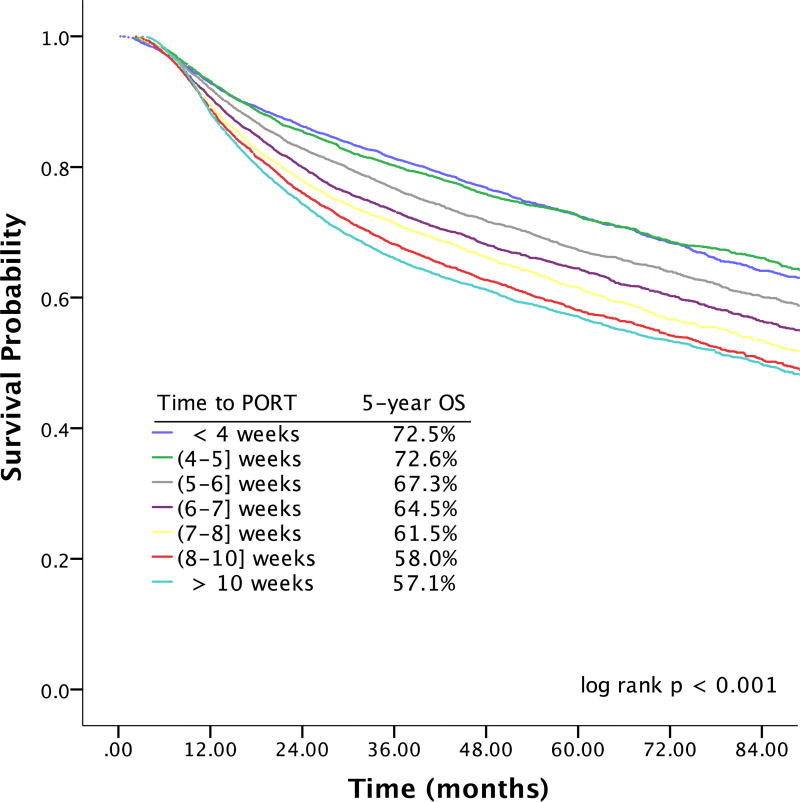

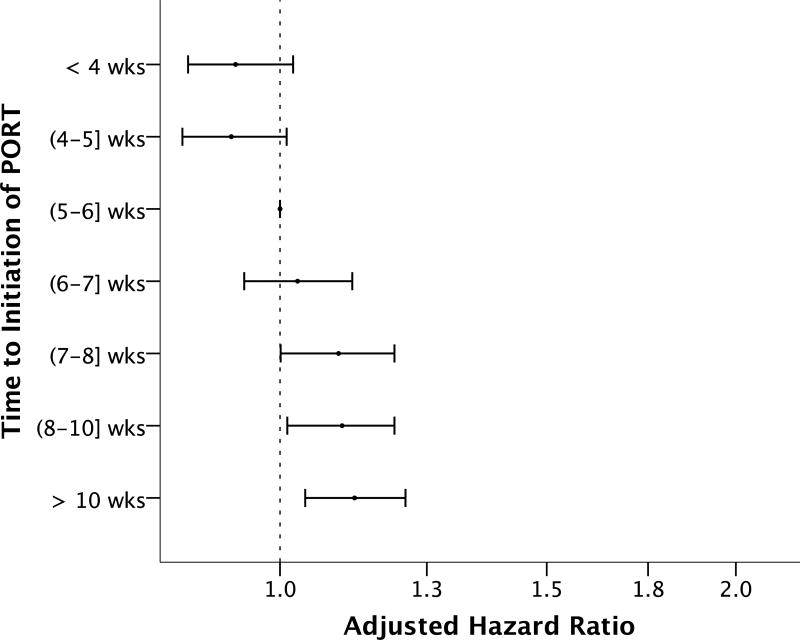

To determine whether earlier time to initiation of PORT was beneficial in terms of OS and whether increasing duration of delays beyond 6 weeks was associated with larger decrements in survival, time to initiation of adjuvant therapy was analyzed as a categorical variable. 15.7% (n=6494) started PORT ≤ 4 weeks of surgery, 13.6% (n=5635) 4 to ≤ 5 weeks postoperatively, 15.3% (n=6333) 5 to ≤ 6 weeks, 14.6% (n=6015) 6 to ≤ 7 weeks, 11.3% (n=4685) 7 to ≤ 8 weeks, 5515 (13.4%) 8 to ≤ 10 weeks, and 16.0% (n=6614) more than 10 weeks following surgery (time interval inclusive of upper bound for each). The Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS for different time to initiation of adjuvant therapy are shown in Figure 3. Relative to starting PORT 5 to ≤ 6 weeks after surgery, initiating adjuvant therapy ≤ 4 weeks of surgery and 4 to ≤ 5 weeks after surgery was associated with significant improvements in OS on univariable analysis (HR 0.84; 99% CI 0.77–0.92 for PORT ≤ 4 weeks postoperatively, HR 0.84; 99% CI 0.76–0.92 for 4 to ≤ 5 weeks). On univariable analysis, increasing duration of delay beyond 6 weeks was associated with progressively larger decreases in OS (HR 1.15; 99% CI 1.06–1.25 for 6 to ≤ 7 weeks, HR 1.26; 99% CI 1.16–1.38 for 7 to ≤ 8 weeks, HR 1.39; 99% CI 1.28–1.51 for 8 to ≤ 10 weeks, HR 1.46; 99% CI 1.35–1.58 for > 10 weeks). Importantly, earlier commencement of adjuvant therapy did not remain associated with improved OS on multivariable analysis adjusting for relevant covariates (Figure 4). Increasing duration of delay beyond 7 weeks postoperatively remained associated with small progressive decrements in OS on multivariable analysis (aHR 1.09; 99% CI 1.00–1.19 for 7 to ≤ 8 wks, aHR 1.10; 99% CI 1.01–1.19 for 8 to ≤ 10 wks, aHR 1.12; 99% CI 1.04–1.21 for > 10 wks; Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3.

| Months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # at Risk | 0 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 | 84 |

| PORT ≤ 4 weeks | 6494 | 5794 | 4863 | 3878 | 3018 | 2186 | 1487 | 940 |

| PORT 4 to ≤ 5 weeks | 5635 | 5019 | 4134 | 3203 | 2458 | 1792 | 1173 | 745 |

| PORT 5 to ≤ 6 weeks | 6333 | 5625 | 4520 | 3446 | 2541 | 1794 | 1218 | 768 |

| PORT 6 to ≤ 7 weeks | 6015 | 5270 | 4137 | 3080 | 2279 | 1651 | 1085 | 682 |

| PORT 7 to ≤ 8 weeks | 4685 | 4078 | 3107 | 2306 | 1686 | 1182 | 727 | 470 |

| PORT 8 to ≤ 10 weeks | 5515 | 4724 | 3538 | 2605 | 1910 | 1319 | 866 | 515 |

| PORT > 10 weeks | 6614 | 5655 | 4253 | 3166 | 2366 | 1664 | 1073 | 640 |

Figure 4.

Legend: Effect of changing time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy (PORT) on overall survival after multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis compared to starting adjuvant therapy between 5–6 weeks after surgery (n=41,291). Estimated hazard ratios are shown by black circles; horizontal lines represent 99% confidence intervals. Each PORT time interval is not inclusive of the lower bound and is inclusive of the upper bound. Analyses are adjusted for age, race, sex, insurance, income, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, primary site, AJCC pathologic stage grouping, concurrent chemotherapy, radiation modality, radiation dose, and duration of radiation.

Discussion

Delivery of quality head and neck cancer care remains a national priority36. Guideline concordant care and timeliness of care are two indicators of quality care1. Risk factors for failing to commence adjuvant therapy in a guideline concordant, timely fashion have been described9. Whether failing to deliver NCCN Guideline-concordant, timely PORT has an impact on survival remains unclear13. This study, which utilized a large national sample of patients from a variety of facility types treated with modern radiation techniques in the era of concurrent chemotherapy, was undertaken to better assess the relationship between quality care, timely care, guideline concordant care, and favorable patient outcomes such as survival.

Oncologic Effect of Guideline-Adherent Initiation of PORT

The rationale for timely initiation of adjuvant radiation is that delays in treatment allow for repopulation and proliferation of residual microscopic disease and tumor clonogens21,24,27,37, with subsequent increases in tumor burden and risk of hypoxia13. Based on mathematical models, it is estimated that persistent postoperative microscopic tumor clonogens repopulate with an estimated doubling time of 40–45 days37,38. This doubling time has been estimated to correspond to a decrease in local control of 0.09%–0.17% for each additional day between surgery and adjuvant therapy25,37.

Despite the NCCN’s endorsement of the preferred time to initiation of PORT for patients with HNSCC, the evidence underlying the recommendation is conflicted with regards to its effect on locoregional recurrence and survival13, with some finding benefit14–21 and others finding no influence10,11,22–26. Many of these studies have been limited by retrospective single institution study design and small patient numbers13. In this study, a 50% relative decrease in overall survival was found for patients who initiate adjuvant therapy more than 6 weeks after surgery, a 15% relative increased risk of death persisted on multivariable analysis adjusting for numerous confounding factors, and a 20% relative increased risk of death in the propensity-matched subset analysis. These findings led further support to the idea that, at least with regards to the timing of adjuvant therapy, guideline-adherent head and neck oncology care is quality care39–41.

Effects of Early Time to Initiation of PORT on Survival

Although NCCN Guidelines recommend initiating PORT within 6 weeks of surgery, it has not been well studied whether there is a benefit to starting adjuvant therapy earlier, such as within 4 or 5 weeks of surgery. Some have advocated commencing adjuvant therapy as soon as possible27. In this current study, there was no statistical or clinically meaningful benefit in terms of overall survival to starting PORT ≤ 4 weeks of surgery or 4 to ≤ 5 weeks of surgery relative to 5 to ≤ 6 weeks after surgery. This may be due to the time course and biology of tumor repopulation. Alternatively, it could be a result of selection bias in which patients perceived as having more aggressive disease are expedited to start adjuvant therapy earlier after surgery, obscuring the beneficial effect of earlier initiation of PORT. It might also be that other end points such as locoregional recurrence are more suitable outcome measures when assessing the effect of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy. Further studies will be required to determine whether there is a benefit overall, or in specific subgroups, to earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy.

Effects of Increasing Duration of Delays to Initiation of PORT on Survival

It also remains understudied whether increasing duration of delays beyond 6 weeks after surgery are associated with correspondingly worse outcomes. In this study, all time intervals for which PORT was initiated more than 7 weeks after surgery were associated with decreased survival, but there were not clinically meaningful differences in the excess risk of death with increasing duration of delays on multivariable analysis. While these data do not support intentionally delaying adjuvant therapy, in cases of prolonged postoperative wound complications in which it is unsafe to start radiation sooner, they show a continued linear increase in the risk of death that comes with increasing duration of delays.

Limitations

This study possesses important limitations. Although the NCDB data is captured by trained data extractors and extensive quality control measures exist, coding errors and data omissions are possible, likely not random, and may bias the results of this study. Although type of surgery is coded within the NCDB, it is likely that some biopsies were coded as definitive surgery, potentially biasing the results. Differentiating between coding errors and outlier data is also challenging and another source of potential error. Because it is a retrospective database study, reasons for delays in starting PORT in a guideline-adherent fashion cannot be discerned. These might include tumor board discussion, patient-physician discussion about the risk/benefit ratio of adjuvant therapy, decision-making in the need for and referral for PORT, patient preferences, indecisiveness, and the ability to access care and meet the schedule of postoperative appointments necessary for timely initiation of PORT. Propensity score matching was used to control for treatment biases of a retrospective observational design, and although successful in balancing differences between the two cohorts of patients, cannot control for variables not captured in the NCDB. Time to initiation of PORT, although it is the only time sensitive metric within current NCCN guidelines, is only one portion of timely care. This study does not evaluate delays in presentation, diagnosis, or initiation of surgery, or total treatment package time from date of surgery to completion of PORT, all of which also impact survival21,42. Overall survival is multifactorial in nature. Although improved OS was seen with guideline-adherent initiation of PORT, it does not imply that timely initiation of PORT indicates improved locoregional control or disease-specific survival. The effect of time to initiation of PORT on rates of locoregional failure or disease-free survival are relevant outcome measures not analyzed in the study because these data are not available in the NCDB; future studies should consider these as outcome measures when evaluating the timeliness of PORT. Despite these limitations, there are numerous methodological strengths to the study. It captures patients of all adult ages, has a national scope, large sample size, and analyzes treatment at different types of hospitals.

Conclusions

Care not adherent to NCCN Guidelines for initiating PORT within 6 weeks of surgery is associated with decreased survival. There is no overall survival benefit to initiating PORT earlier within the recommended 6-week timeframe. Increasing durations of delay beyond 7 weeks are associated with small progressive survival decrements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shai White-Gilbertson, PhD, for her assistance with the National Cancer Data Base.

Funding Sources: This research was supported by the Biostatistics Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313)

Footnotes

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest: None

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content;

- final approval of the version to be published;

- agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The NCDB is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The data used in the study are derived from a de-identified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

References

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(NQMC). NQMC. [Accessed January 3 2017];Measure summary: Access: time to third next available appointment for an office visit. Available at: https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/

- 3.Kaplan G, Lopez MH, McGinnis JM. Transforming Healthcare Scheduling and Access: Getting to Now. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt M, Simone J. National Cancer Policy Board: Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz P. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Ensuring quality cancer care by the use of clinical practice guidelines and critical pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2886–2897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach P. Using practice guidelines to assess cancer care quality. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9041–9043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Network NCC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Head and Neck Cancers. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graboyes EM, Garrett-Mayer E, Sharma AK, Lentsch EJ, Day TA. Adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for time to initiation of postoperative radiation therapy for patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cncr.30651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graboyes EM, Gross J, Kallogjeri D, et al. Association of Compliance With Process-Related Quality Metrics and Improved Survival in Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2016;142:430–437. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graboyes EM, Townsend ME, Kallogjeri D, Piccirillo JF, Nussenbaum B. Evaluation of Quality Metrics for Surgically Treated Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2016;142:1154–1163. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshak G, Popovtzer A. Is there any significant reduction of patients’ outcome following delay in commencing postoperative radiotherapy? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:82–84. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193177.62074.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vikram B. Importance of the time interval between surgery and postoperative radiation therapy in the combined management of head & neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:1837–1840. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vikram B, Strong EW, Shah JP, Spiro R. Failure in the neck following multimodality treatment for advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck Surg. 1984;6:724–729. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons JT, Mendenhall WM, Stringer SP, Cassisi NJ, Million RR. An analysis of factors influencing the outcome of postoperative irradiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muriel VP, Tejada MR, de Dios Luna del Castillo J. Time-dose-response relationships in postoperatively irradiated patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, Browman G, Mackillop WJ. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:555–563. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byers RM, Clayman GL, Guillamondequi OM, Peters LJ, Goepfert H. Resection of advanced cervical metastasis prior to definitive radiotherapy for primary squamous carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Head Neck. 1992;14:133–138. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaikh T, Handorf EA, Murphy CT, Mehra R, Ridge JA, Galloway TJ. The Impact of Radiation Treatment Time on Survival in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiff PB, Harrison LB, Strong EW, et al. Impact of the time interval between surgery and postoperative radiation therapy on locoregional control in advanced head and neck cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43:203–208. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastit L, Blot E, Debourdeau P, Menard J, Bastit P, Le Fur R. Influence of the delay of adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy on relapse and survival in oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenthal DI, Liu L, Lee JH, et al. Importance of the treatment package time in surgery and postoperative radiation therapy for squamous carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2002;24:115–126. doi: 10.1002/hed.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suwinski R, Sowa A, Rutkowski T, Wydmanski J, Tarnawski R, Maciejewski B. Time factor in postoperative radiotherapy: a multivariate locoregional control analysis in 868 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshak G, Rakowsky E, Schachter J, et al. Is the delay in starting postoperative radiotherapy a key factor in the outcome of advanced (T3 and T4) laryngeal cancer? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackillop WJ, Bates JH, O’Sullivan B, Withers HR. The effect of delay in treatment on local control by radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:243–250. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghazali N, Hanna TC, Dyalram D, Lubek JE. The Value of the “Papillon” Anterolateral Thigh Flap for Total Pharyngolaryngectomy Reconstruction: A Retrospective Case Series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity-score methods for estimating differences in proportions (risk differences or absolute risk reductions) in observational studies. Stat Med. 2010;29:2137–2148. doi: 10.1002/sim.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10:150–161. doi: 10.1002/pst.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med. 2013;32:2837–2849. doi: 10.1002/sim.5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fakhry C, Gillison ML. Clinical implications of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2606–2611. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Accessed April 20 2017];Oropharynx CS Ciste-Specific Factor 10: Human papillomavirus (HPV) status. Available at: http://web2.facs.org/cstage0205/oropharynx/Oropharynx_spd.html.

- 36.Weber RS. Improving the quality of head and neck cancer care. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2007;133:1188–1192. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.12.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Dweri FM, Guirado D, Lallena AM, Pedraza V. Effect on tumour control of time interval between surgery and postoperative radiotherapy: an empirical approach using Monte Carlo simulation. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:2827–2839. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/13/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steel G. Basic clinical radiobiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. The growth rate of tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eskander A, Monteiro E, Irish J, et al. Adherence to guideline-recommended process measures for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in Ontario: Impact of surgeon and hospital volume. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1987–1992. doi: 10.1002/hed.24364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis CM, Nurgalieva Z, Sturgis EM, Lai SY, Weber RS. Improving patient outcomes through multidisciplinary treatment planning conference. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1820–1825. doi: 10.1002/hed.24325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hessel AC, Moreno MA, Hanna EY, et al. Compliance with quality assurance measures in patients treated for early oral tongue cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:3408–3416. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy CT, Galloway TJ, Handorf EA, et al. Survival Impact of Increasing Time to Treatment Initiation for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:169–178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.