Abstract

Background

Diarrhea caused by opportunistic intestinal protozoa is a common problem in HIV infection. We aimed to establish the prevalence of Cryptosporidium, misrosporidia, and Isospora in HIV-infected people using a systematic review and meta-analysis, which is central to developing public policy and clinical services.

Methods

We searched PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Embase, Chinese Web of Knowledge, Wanfang, and Chongqing VIP databases for studies reporting Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, or Isospora infection in HIV-infected people. We extracted the numbers of people with HIV and protozoa infection, and estimated the pooled prevalence of parasite infection by a random effects model.

Results

Our research identified 131 studies that reported Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people. We estimated the pooled prevalence to be 14.0% (3283/43,218; 95% CI: 13.0–15.0%) for Cryptosporidium, 11.8% (1090/18,006; 95% CI: 10.1–13.4%) for microsporidia, and 2.5% (788/105,922; 95% CI: 2.1–2.9%) for Isospora. A low prevalence of microsporidia and Isospora infection was found in high-income countries, and a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Isospora infection was found in sub-Saharan Africa. We also detected a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, and Isospora infection in patients with diarrhea. Sensitivity analysis showed that three studies significantly affect the prevalence of Isospora, which was adjusted to 5.0% (469/8570; 95% CI: 4.1–5.9%) by excluding these studies.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that HIV-infected people have a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, and Isospora infection in low-income countries and patients with diarrhea, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, reinforcing the importance of routine surveillance for opportunistic intestinal protozoa in HIV-infected people.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-017-2558-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HIV, Cryptosporidium, Microsporidia, Isospora, Meta-analysis

Background

Despite the advance of antiretroviral therapy (ART), diarrhea is still a common problem of HIV infection and contributes to the reduced life quality and survival of HIV patients [1, 2]. It is estimated that diarrhea occurs in roughly 90% HIV/AIDS patients in developing countries, and 30–60% in developed countries [3]. Opportunistic pathogens that cause diarrhea in HIV-infected people include protozoa, fungi, viruses, and bacteria [4]. Several protozoan species belonging to Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora, are among the most common causative pathogens responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in HIV patients [5].

With a worldwide distribution of Cryptosporidium, C. parvum and C. hominis are the most common species detected in humans, though other species, including C. meleagridis, C. felis and C. canis, have also been reported [6]. Despite the use of ART in many countries of the world, the infection rates of Cryptosporidium in HIV patients are still high, accounting for up to a third of diarrhea cases in HIV patients [7].

Microsporidia are obligate intracellular eukaryotic pathogens, which are phylogenetically related to fungi, and have been considered as opportunistic infections in both developed and developing countries, especially in HIV patients with a CD4 cell count below 100 cells/μl [8]. Of the 15 species of microsporidia that infect humans, Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon intestinalis can cause gastrointestinal diseases, with E. bieneusi being the more commonly identified species in HIV-infected people [9].

Isospora belli is the only species of the genus Isospora, and is frequently found in HIV-infected people of tropical and subtropical regions, accounting for up to 20% of diarrhea cases in AIDS patients [7]. The species can cause acute self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals, but in severely immunocompromised patients, this parasite can cause severe chronic diarrhea which may result in a wasting syndrome, or even the death of AIDS patients [10].

The opportunistic parasites Cryptosporidium spp., microsporidians and Isospora spp. develop in enterocytes, and are excreted via feces and transmitted through the fecal-oral route via ingestion of contaminated water or food, or direct contact with infected animals or humans [11]. HIV-infected people are more likely to develop abrupt, severe, and explosive diarrhea when infected with opportunistic protozoa than immunocompetent individuals. Millions of people are affected by the morbidity caused by these parasites, as there was an estimated 36.7 million people living with HIV in 2015 worldwide [12]. Since there is no reliable or well-defined treatment for the protozoan infections in immunocompromised patients [1], understanding their epidemiology is central in formulating effective control strategies against cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, and isosporiasis in these populations. We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the worldwide prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in people with HIV.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Embase, Chinese Web of Knowledge, Wanfang, and Chongqing VIP databases for studies reporting Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, or Isospora infection in HIV-infected people from inception to 31 December 2016. The databases were searched using the term “Cryptosporidium”, “cryptosporidiosis”, “microsporidia”, “microsporidiosis”, “Isospora” or “isosporiasis” cross-referenced with “HIV”, “immunodeficiency”, “acquired immune deficiency syndrome”, or “AIDS”, without language restriction. We did our analyses according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13] (see PRISMA checklist in Additional file 1: Table S1).

Selection criteria

The included studies were required to investigate HIV-infected people and needed to have data that allowed us to calculate the prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, and Isospora infection. We excluded studies if they were reviews, animal studies, or repeated studies; if there were no raw data; if the sample size was less than 20; or if the diagnostic methods of parasite infection were unclear.

Two independent reviewers (LZ and SL) carefully examined all titles and abstracts identified in the search, and assessed the full text considered potentially relevant. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with other two authors (Z-DW and H-HL).

Data analysis

Two reviewers (Z-DW and SL) extracted the information about the first author, publication year, country of the study, numbers of HIV-infected people and Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, or Isospora co-infected people, diagnostic methods, study design, and demographic characteristics from each eligible study, and reached a consensus after discussing any controversial finding.

We assessed the quality of the included publications on the basis of criteria derived from the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation method [14]. We used a scoring approach to grade quality. Studies were given one point each if they had probability sampling, larger sample sizes of more than 200, and repeated detection. Up to four points could be assigned to each study. We regarded publications with a total score of three or four points to be of high quality, whereas two points represented moderate quality and scores of one or zero represented low quality.

We did a meta-analysis by a random-effects model or fixed-effects model to calculate the pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia, or Isospora infection using Stata version 12.

The heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q and the I2-statistic, which presents the percentage of variation between studies. Due to high heterogeneity (I2 > 50%, P < 0.1), random effects models were used for summary statistics. A potential source of heterogeneity was investigated by subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis. We examined factors both individually and in multiple-variable models to determine the possible factors that caused heterogeneity in our study. The factors included geographical region by comparison of sub-Sahara Africa with other regions, income level by comparison of low-income countries with others, and patients with diarrhea by comparison of patients with diarrhea with others. We also evaluated the effect of selected studies on the pooled prevalence by excluding single studies sequentially. A study was considered to have no influence if the pooled estimate without it was within the 95% confidence limits of the overall prevalence [15].

Results

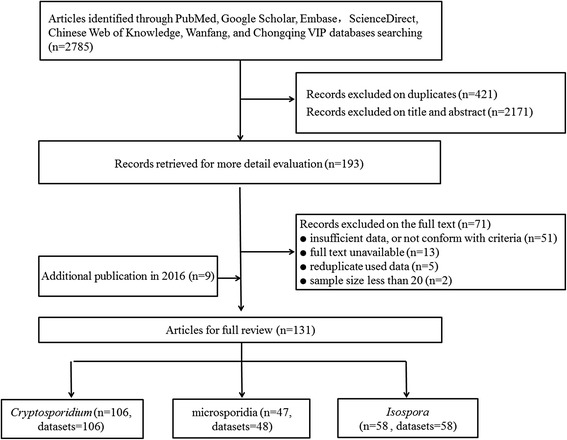

Our research identified 2785 records. After initial screening and removal of duplicates, 193 papers were reviewed in full. Of these, 51 articles did not include sufficient data that were required or conform to the criteria, 13 were unavailable for full text, five had duplicate samples, and two included the sample size of less than 20. After an updated search, nine papers were included and we had 131 articles for quality assessment and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process

According to our criteria, 51 publications were of high quality with a score of three or four, 48 had a score of two indicating moderate quality, and the remaining 32 were of low quality with a score of zero or one (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Included studies of Cryptosporidium infection in people with HIV listed in order of year published

| Country | Income level | Patients with diarrhea | No. of patients | Prevalence (%) | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western and central Europe and North America | ||||||

| René et al. (1989) [37] | France | High | Mixed | 132 | 21.2 | 2 |

| Connolly et al. (1990) [53] | UK | High | Yes | 33 | 15.2 | 1 |

| Brandonisio et al. (1993) [54] | Italy | High | Yes | 51 | 33.3 | 1 |

| Sorvillo et al. (1994) [41] | USA | High | Mixed | 16,953 | 3.8 | 2 |

| Colford et al. (1996) [34] | USA | High | Mixed | 3564 | 5.4 | 3 |

| Mathewson et al. (1998) [42] | USA | High | Yes | 83 | 10.8 | 2 |

| Matos et al. (1998) [35] | Portugal | High | Yes | 465 | 7.7 | 3 |

| Brandonisio et al. (1999) [38] | Italy | High | Mixed | 154 | 11.0 | 3 |

| Cama et al. (2006) [55] | USA | High | Mixed | 21 | 33.3 | 1 |

| Lagrange-Xelot et al. (2008) [27] | France | High | Mixed | 6827 | 1.3 | 1 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||

| Henry et al. (1986) [32] | DR Congo | Low | Yes | 46 | 8.7 | 0 |

| Colebunders et al. (1988) [56] | DR Congo | Low | Yes | 42 | 31.0 | 0 |

| Therizol-Ferly et al. (1989) [57] | Ivory Coast | Middle | Yes | 148 | 6.8 | 1 |

| Hunter et al. (1992) [58] | Zambia | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 2.2 | 2 |

| Assoumou et al. (1993) [59] | Ivory Coast | Middle | Mixed | 217 | 8.8 | 1 |

| Dieng et al. (1994) [60] | Senegal | Low | Yes | 72 | 13.9 | 1 |

| Chintu et al. (1995) [61] | Zambia | Middle | Yes | 44 | 13.6 | 2 |

| Mwachari et al. (1998) [62] | Kenya | Middle | Yes | 75 | 17.3 | 2 |

| Fisseha et al. (1999) [63] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 190 | 20.0 | 2 |

| Gumbo et al. (1999) [31] | Zimbabwe | Low | Yes | 82 | 8.5 | 2 |

| Cegielski et al. (1999) [64] | Tanzania | Low | Yes | 86 | 7.0 | 2 |

| Lebbad et al. (2001) [65] | Guinea-Bissau | Low | Yes | 37 | 21.6 | 2 |

| Nwokediuko et al. (2002) [66] | Nigeria | Middle | Yes | 161 | 0.0 | 1 |

| Adjei et al. (2003) [67] | Ghana | Middle | Yes | 21 | 28.6 | 2 |

| Tumwine et al. (2005) [28] | Uganda | Low | Yes | 91 | 73.6 | 2 |

| Tadesse et al. (2005) [68] | Ethiopia | Low | Yes | 70 | 28.6 | 1 |

| Sarfati et al. (2006) [69] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 154 | 9.7 | 3 |

| Adesiji et al. (2007) [29] | Nigeria | Middle | Yes | 100 | 79.0 | 3 |

| Mariam et al. (2008) [70] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 109 | 7.3 | 2 |

| Blanco et al. (2009) [71] | Equatorial Guinea | Middle | na | 171 | 18.1 | 3 |

| Cooke et al. (2009) [72] | South Africa | Middle | Mixed | 26 | 7.7 | 0 |

| Babatunde et al. (2010) [73] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 32.2 | 1 |

| Alemu et al. (2011) [74] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 188 | 43.6 | 1 |

| Bartelt et al. (2011) [30] | South Africa | Middle | na | 193 | 75.6 | 1 |

| Roka et al. (2012) [75] | Equatorial Guinea | Middle | Mixed | 260 | 9.2 | 4 |

| Wumba et al. (2012) [76] | DR Congo | Low | Mixed | 242 | 5.4 | 4 |

| Nwuba et al. (2012) [33] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 202 | 30.7 | 3 |

| Girma et al. (2014) [77] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 268 | 34.3 | 3 |

| Samie et al. (2014) [78] | South Africa | Middle | Mixed | 151 | 26.5 | 2 |

| Vouking et al. (2014) [79] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 207 | 7.2 | 3 |

| Bissong et al. (2015) [80] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 7.0 | 3 |

| Kiros et al. (2015) [81] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 399 | 5.8 | 3 |

| Nsagha et al. (2016) [39] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 300 | 44.0 | 4 |

| Shimelis et al. (2016) [3] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 491 | 13.2 | 3 |

| Ojuromi et al. (2016) [82] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 4.4 | 3 |

| Asia and the Pacific | ||||||

| Kamel et al. (1994) [83] | Malaysia | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 23.0 | 0 |

| Moolasart et al. (1995) [84] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 250 | 8.8 | 2 |

| Anand et al. (1996) [85] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 35.0 | 1 |

| Punpoowong et al. (1998) [86] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 22 | 9.1 | 0 |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. (1999) [87] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 91 | 25.3 | 2 |

| Prasad et al. (2000) [88] | India | Middle | Mixed | 26 | 11.5 | 2 |

| Wiwanitkit et al. (2001) [89] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 60 | 3.3 | 1 |

| Chokephaibulkit et al. (2001) [90] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 82 | 6.1 | 2 |

| Waywa et al. (2001) [91] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 288 | 19.1 | 3 |

| Kumar et al. (2002) [92] | India | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 14.0 | 2 |

| Mohandas et al. (2002) [93] | India | Middle | Mixed | 120 | 10.8 | 3 |

| Lim et al. (2005) [94] | Malaysia | Middle | Mixed | 66 | 3.0 | 1 |

| Guk et al. (2005) [95] | South Korea | High | Mixed | 67 | 10.4 | 1 |

| Chhin et al. (2006) [96] | Cambodia | Middle | Yes | 80 | 45.0 | 3 |

| Dwivedi (2007) [48] | India | Middle | Mixed | 75 | 33.3 | 2 |

| Ramakrishnan et al. (2007) [97] | India | Middle | Yes | 80 | 28.8 | 2 |

| Qu et al. (2007) [19] | China | Middle | Yes | 141 | 3.5 | 0 |

| Stark et al. (2007) [98] | Australia | High | Yes | 618 | 2.3 | 4 |

| Saldanha et al. (2008) [99] | India | Middle | na | 307 | 17.3 | 1 |

| Jayalakshmi et al. (2008) [43] | India | Middle | Yes | 89 | 12.4 | 2 |

| Viriyavejakul et al. (2009) [100] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 64 | 20.3 | 2 |

| Saksirisampant et al. (2009) [101] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 34.4 | 1 |

| Kulkarni et al. (2009) [44] | India | Middle | Yes | 137 | 11.7 | 1 |

| Guo et al. (2011) [20] | China | Middle | Yes | 149 | 16.1 | 2 |

| Tian et al. (2012) [102] | China | Middle | na | 302 | 8.3 | 4 |

| Tian et al. (2012) [22] | China | Middle | Mixed | 46 | 13.0 | 3 |

| Li et al. (2012) [21] | China | Middle | Yes | 67 | 6.0 | 2 |

| Wang et al. (2012) [23] | China | Middle | Yes | 253 | 12.6 | 3 |

| Sherchan et al. (2012) [103] | Nepal | Low | Mixed | 146 | 2.7 | 3 |

| Wang et al. (2013) [9] | China | Middle | Mixed | 673 | 1.5 | 4 |

| Mehta et al. (2013) [104] | India | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 2.0 | 3 |

| Vyas et al. (2013) [105] | India | Middle | Yes | 75 | 14.7 | 2 |

| Gupta et al. (2013) [45] | India | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 4.0 | 2 |

| Baragundi Mahesh et al. (2013) [106] | India | Middle | Mixed | 75 | 18.7 | 2 |

| Paboriboune et al. (2014) [107] | Laos | Middle | Mixed | 137 | 6.6 | 3 |

| Jain et al. (2014) [108] | India | Middle | Mixed | 250 | 20.8 | 2 |

| Pang et al. (2015) [16] | China | Middle | na | 450 | 17.3 | 3 |

| Angal et al. (2015) [109] | Malaysia | Middle | Mixed | 131 | 3.8 | 3 |

| Xie et al. (2015) [17] | China | Middle | Mixed | 152 | 13.2 | 0 |

| Khalil et al. (2015) [110] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 7.5 | 3 |

| Asma et al. (2015) [111] | Malaysia | Middle | Mixed | 346 | 12.4 | 4 |

| Kaniyarakkal et al. (2016) [112] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 2.5 | 2 |

| Mitra et al. (2016) [113] | India | Middle | Mixed | 194 | 29.4 | 2 |

| Shah et al. (2016) [114] | India | Middle | Mixed | 45 | 13.3 | 2 |

| Wang et al. (2016) [18] | China | Middle | Mixed | 285 | 0.7 | 4 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||||||

| Chacin-Bonilla et al. (1992) [115] | Venezuela | High | Mixed | 29 | 41.4 | 1 |

| Escobedo et al. (1999) [116] | Cuba | Middle | Mixed | 67 | 11.9 | 2 |

| Florez et al. (2003) [117] | Colombia | Middle | Mixed | 115 | 10.4 | 3 |

| Ribeiro et al. (2004) [118] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 75 | 9.3 | 2 |

| Chacin et al. (2006) [119] | Venezuela | High | Yes | 103 | 25.2 | 2 |

| Goncalves et al. (2009) [120] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 9.0 | 2 |

| Cardoso et al. (2011) [121] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 500 | 0.2 | 3 |

| Velasco et al. (2011) [122] | Colombia | Middle | Mixed | 131 | 29.0 | 2 |

| Guimarães et al. (2012) [123] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 93 | 2.2 | 1 |

| Assis et al. (2013) [124] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 59 | 10.2 | 2 |

| Middle East and North Africa | ||||||

| Zali et al. (2004) [125] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 206 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Yosefi et al. (2012) [126] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 60 | 8.3 | 2 |

| Agholi et al. (2013) [127] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 356 | 9.6 | 3 |

| Salehi Sangani et al. (2016) [128] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 80 | 1.3 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | ||||||

| Brannan et al. (1996) [129] | Romania | Middle | Mixed | 73 | 78.1 | 3 |

| Kucervoa et al. (2011) [130] | Russia | Middle | na | 46 | 41.3 | 2 |

Abbreviations: Yes, patients with diarrhea; Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea; na, not applicable (parameter not provided)

Table 2.

Included studies of microsporidia infection in people with HIV listed in order of year published

| Country | Income level | Patients with diarrhea | No. of patients | Prevalence (%) | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western and central Europe and North America | ||||||

| Weber et al. (1992) [131] | USA | High | Mixed | 134 | 4.5 | 2 |

| Kotler et al. (1994) [132] | USA | High | Mixed | 194 | 28.9 | 3 |

| Anwar-Bruni et al. (1996) [36] | USA | High | Mixed | 371 | 5.9 | 4 |

| Coyle et al. (1996) [133] | USA | High | Mixed | 111 | 27.9 | 3 |

| Mathewson et al. (1998) [42] | USA | High | Yes | 83 | 6.0 | 2 |

| Brandonisio et al. (1999) [38] | Italy | High | Mixed | 154 | 4.5 | 3 |

| Ferreira et al. (2001) [134] | Portugal | High | Yes | 215 | 42..8 | 4 |

| Lagrange-Xelot et al. (2008) [27] | France | High | Mixed | 6827 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||

| van Gool et al. (1995) [135] | Zimbabwe | Low | Yes | 129 | 10.1 | 2 |

| Maiga et al. (1997) [24] | Mali | Low | Mixed | 77 | 32.5 | 1 |

| Mwachari et al. (1998) [62] | Kenya | Middle | Yes | 36 | 2.8 | 2 |

| Cegielski et al. (1999) [64] | Tanzania | Low | Yes | 86 | 3.5 | 2 |

| Gumbo et al. (1999) [31] | Zimbabwe | Low | Yes | 55 | 50.9 | 2 |

| Lebbad et al. (2001) [65] | Guinea-Bissau | Low | Yes | 37 | 8.1 | 2 |

| Endeshaw et al. (2005) [136] | Ethiopia | Low | Yes | 80 | 22.5 | 1 |

| Tumwine et al. (2005) [28] | Uganda | Low | Yes | 91 | 76.9 | 2 |

| Endeshaw et al. (2006) [137] | Ethiopia | Low | Yes | 214 | 18.2 | 3 |

| Sarfati et al. (2006) [69] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 154 | 5.2 | 3 |

| Breton et al. (2007) [138] | Gabon | Middle | na | 822 | 3.0 | 4 |

| Breton et al. (2007) [138] | Cameroon | Middle | na | 758 | 2.9 | 4 |

| Akinbo et al. (2012) [139] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 463 | 16.6 | 3 |

| Wumba et al. (2012) [76] | DR Congo | Low | Mixed | 242 | 8.3 | 4 |

| Bissong et al. (2015) [80] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 2.0 | 3 |

| Nsagha et al. (2016) [39] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 300 | 21.3 | 4 |

| Ojuromi et al. (2016) [82] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 5.6 | 3 |

| Asia and the Pacific | ||||||

| Punpoowong et al. (1998) [86] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 22 | 27.3 | 0 |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. (1998) [140] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 66 | 33.3 | 3 |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. (1999) [87] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 91 | 28.6 | 2 |

| Chokephaibulkit et al. (2001) [90] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 82 | 19.5 | 2 |

| Wiwanitkit et al. (2001) [89] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 60 | 1.7 | 1 |

| Waywa et al. (2001) [91] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 288 | 9.7 | 3 |

| Kumar et al. (2002) [92] | India | Middle | Mixed | 150 | 0.7 | 2 |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. (2002) [141] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 95 | 25.3 | 2 |

| Mohandas et al. (2002) [93] | India | Middle | Mixed | 120 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Dwivedi et al. (2007) [48] | India | Middle | Mixed | 75 | 6..7 | 2 |

| Saksirisampant et al. (2009) [101] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 5.6 | 1 |

| Viriyavejakul et al. (2009) [100] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 64 | 81.3 | 2 |

| Kulkarni et al. (2009) [44] | India | Middle | Yes | 137 | 1.5 | 1 |

| Wang et al. (2013) [9] | China | Middle | Mixed | 683 | 5.7 | 4 |

| Xie et al. (2015) [17] | China | Middle | Mixed | 152 | 5.3 | 0 |

| Khalil et al. (2015) [110] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Khanduja et al. (2016) [8] | India | Middle | Mixed | 222 | 1.8 | 4 |

| Mitra et al. (2016) [113] | India | Middle | Mixed | 194 | 2.1 | 2 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||||||

| Florez et al. (2003) [117] | Colombia | Middle | Mixed | 115 | 3.5 | 3 |

| Sulaiman et al. (2003) [142] | Peru | Middle | Mixed | 2672 | 3.9 | 4 |

| Chacin-Bonilla et al. (2006) [119] | Venezuela | High | Mixed | 103 | 13.6 | 1 |

| Middle East and North Africa | ||||||

| Agholi et al. (2013) [127] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 356 | 2.2 | 3 |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | ||||||

| Kucerova et al. (2011) [130] | Russia | Middle | na | 46 | 13.0 | 2 |

Abbreviations: Yes, patients with diarrhea; Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea; na, not applicable (parameter not provided)

Table 3.

Included studies of Isospora infection in people with HIV listed in order of year published

| Country | Income level | Patients with diarrhea | No of patients | Prevalence (%) | Quality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western and central Europe and North America | ||||||

| René et al. (1989) [37] | France | High | Mixed | 132 | 0.8 | 2 |

| Sorvillo et al. (1995) [25] | USA | High | Mixed | 16,351 | 0.8 | 2 |

| Mathewson et al. (1998) [42] | USA | High | Yes | 83 | 3.6 | 2 |

| Brandonisio et al. (1999) [38] | Italy | High | Mixed | 154 | 0.6 | 3 |

| Guiguet et al. (2007) [143] | France | High | Mixed | 74,174 | 0.2 | 2 |

| Lagrange-Xelot et al. (2008) [27] | France | High | Mixed | 6827 | 0.4 | 1 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||

| Henry et al. (1986) [32] | DR Congo | Low | Yes | 46 | 19.6 | 0 |

| Colebunders et al. (1988) [56] | DR Congo | Low | Yes | 42 | 11.9 | 0 |

| Therizol-Ferly et al. (1989) [57] | Ivory Coast | Middle | Yes | 148 | 16.2 | 1 |

| Hunter et al. (1992) [58] | Zambia | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 7.8 | 2 |

| Dieng et al. (1994) [60] | Senegal | Low | Yes | 72 | 15.3 | 1 |

| Fisseha et al. (1999) [63] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 190 | 1.6 | 2 |

| Lebbad et al. (2001) [65] | Guinea-Bissau | Low | Yes | 37 | 10.8 | 2 |

| Keshinro et al. (2003) [26] | Nigeria | Middle | Yes | 40 | 7.5 | 1 |

| Sarfati et al. (2006) [69] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 154 | 1.9 | 3 |

| Mariam et al. (2008) [70] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 109 | 1.8 | 2 |

| Babatunde et al. (2010) [73] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 11.1 | 1 |

| Alemu et al. (2011) [74] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 188 | 15.4 | 1 |

| Wumba et al. (2012) [144] | DR Congo | Low | Mixed | 242 | 2.9 | 4 |

| Abaver et al. (2012) [145] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 480 | 1.7 | 3 |

| Nwuba et al. (2012) [33] | Nigeria | Middle | Mixed | 202 | 24.3 | 3 |

| Vouking et al. (2014) [79] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 207 | 5.8 | 3 |

| Girma et al. (2014) [77] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 268 | 1.5 | 3 |

| Bissong et al. (2015) [80] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 6.5 | 3 |

| Kiros et al. (2015) [81] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 399 | 1.3 | 3 |

| Nsagha et al. (2016) [39] | Cameroon | Middle | Mixed | 300 | 4.3 | 4 |

| Shimelis et al. (2016) [3] | Ethiopia | Low | Mixed | 491 | 2.2 | 3 |

| Asia and the Pacific | ||||||

| Punpoowong et al. (1998) [86] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 22 | 4.5 | 0 |

| Wanachiwanawin et al. (1999) [87] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 91 | 7.7 | 2 |

| Mukhopadhya et al. (1999) [146] | India | Middle | Mixed | 111 | 12.6 | 1 |

| Prasad et al. (2000) [88] | India | Middle | Yes | 26 | 26.9 | 2 |

| Waywa et al. (2001) [91] | Thailand | Middle | Yes | 288 | 4.5 | 3 |

| Wiwanitkit et al. (2001) [89] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 60 | 5.0 | 1 |

| Mohandas et al. (2002) [93] | India | Middle | Mixed | 120 | 2.5 | 3 |

| Kumar et al. (2002) [92] | India | Middle | Mixed | 150 | 9.3 | 2 |

| Guk et al. (2005) [95] | South Korea | High | Mixed | 67 | 7.5 | 1 |

| Dwivedi et al. (2007) [48] | India | Middle | Yes | 75 | 2.7 | 2 |

| Jayalakshmi et al. (2008) [43] | India | Middle | Yes | 89 | 3.4 | 2 |

| Saksirisampant et al. (2009) [101] | Thailand | Middle | Mixed | 90 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Kulkarni et al. (2009) [44] | India | Middle | Yes | 137 | 8.0 | 1 |

| Sherchan et al. (2012) [103] | Nepal | Low | Mixed | 146 | 2.1 | 3 |

| Baragundi Mahesh et al. (2013) [106] | India | Middle | Mixed | 75 | 9.3 | 2 |

| Vyas et al. (2013) [105] | India | Middle | Yes | 75 | 12.0 | 2 |

| Mehta et al. (2013) [104] | India | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 18.0 | 3 |

| Gupta et al. (2013) [45] | India | Middle | Mixed | 100 | 25.0 | 2 |

| Jain et al. (2014) [108] | India | Middle | Mixed | 250 | 0.8 | 2 |

| Paboriboune et al. (2014) [107] | Laos | Middle | Mixed | 137 | 4.4 | 3 |

| Khalil et al. (2015) [110] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 7.5 | 3 |

| Kaniyarakkal et al. (2016) [112] | India | Middle | Mixed | 200 | 4.5 | 2 |

| Mitra et al. (2016) [113] | India | Middle | Mixed | 194 | 14.4 | 2 |

| Shah et al. (2016) [114] | India | Middle | Mixed | 45 | 20.0 | 2 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||||||

| Escobedo et al. (1999) [116] | Cuba | Middle | Mixed | 67 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Moran et al. (2005) [147] | Mexico | Middle | Mixed | 203 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Cardoso et al. (2011) [121] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 500 | 1.2 | 3 |

| Guimarães et al. (2012) [123] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 93 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Assis et al. (2013) [124] | Brazil | Middle | Mixed | 59 | 6.8 | 2 |

| Middle East and North Africa | ||||||

| Agholi et al. (2013) [127] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 356 | 0.6 | 3 |

| Salehi Sangani et al. (2016) [128] | Iran | Middle | Mixed | 80 | 2.5 | 2 |

Abbreviations: Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea; Yes, patients with diarrhea

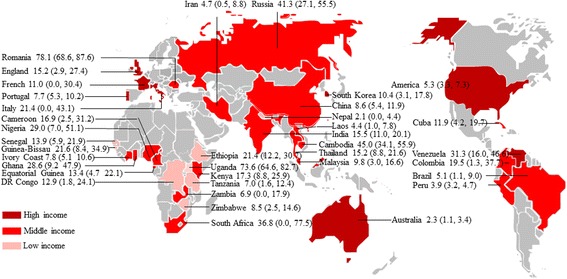

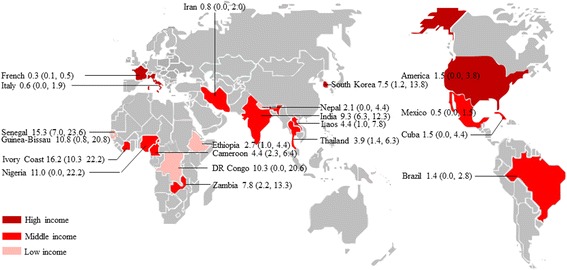

One hundred and six studies assessed Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people (Fig. 1, Table 1), including a total of 43,218 HIV-infected patients. These studies were done in 36 countries (Fig. 2), including five countries of western and central Europe and North America, 15 of sub-Saharan Africa, four of Latin America and the Caribbean, two of eastern Europe and central Asia, nine of Asia and the Pacific, and one of Middle East and North Africa. Of these identified studies, 16 were done in low-income countries, 76 were in middle-income countries, and 14 were in high-income countries (Fig. 2). Ninety-eight papers were written in English, and eight in Chinese [16–23].

Fig. 2.

Map of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people worldwide. Pooled percentage prevalence and 95% CI are shown for each country

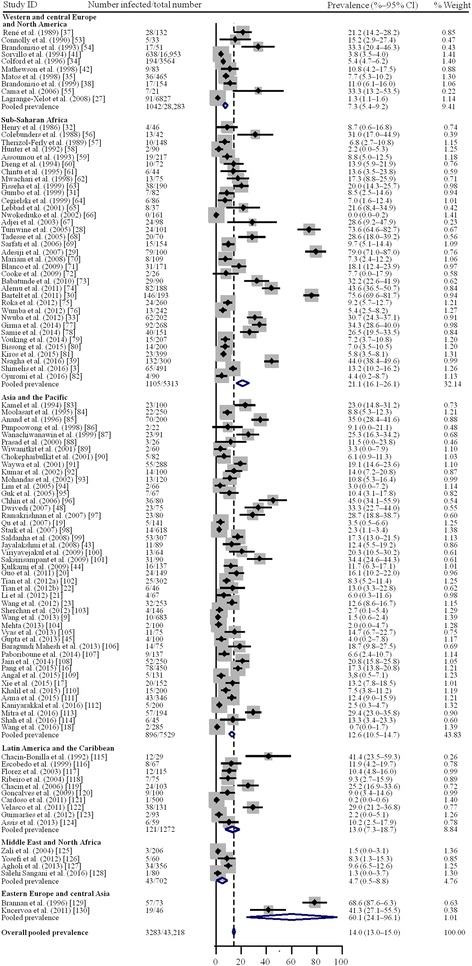

The prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection ranged between 0 and 78.1% (Fig. 3). Meta-analysis by random-effect model showed that the estimated pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in people with HIV infection was 14.0% (3283/43,218; 95% CI: 13.0–15.0%) overall, 21.1% (1105/5315; 95% CI: 16.1–21.1%) in sub-Saharan Africa, 7.3% (1042/28,283; 95% CI: 5.4–9.2%) in western and central Europe and North America, 12.6% (896/7529; 95% CI: 10.5–14.7%) in Asia and the Pacific, 13.0% (121/1272; 95% CI: 7.3–18.7%) in Latin America and the Caribbean, 4.7% (43/702; 95% CI: 0.5–8.8%) in the Middle East and North Africa, and 60.1% (76/119; 95% CI: 24.1–96.1%) in eastern Europe and central Asia. Only four studies were done in Middle East and North Africa, and two in eastern Europe and central Asia, where the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people was very poorly recorded.

Fig. 3.

Random-effect meta-analysis of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people

With a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 97.6%, P < 0.0001; Table 4), meta-regression analyses showed that geographical distribution (P = 0.039) and patients with diarrhea (P = 0.009) might be sources of heterogeneity, whereas we detected no significant differences in income levels (P = 0.328). Subgroup analysis showed the pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people was significantly lower in western and central Europe and North America than in sub-Saharan Africa (OR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.54–0.99, P = 0.044), and higher in patients with diarrhea (OR 1.21, 95% CI: 1.00–1.46, P = 0.047).

Table 4.

Pooled prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected patients

| No. of studies | No. of HIV-infected patients | No. of patients with Cryptosporidium co-infection | Prevalence of Cryptosporidium co-infection (95% CI) (%) | Heterogeneity | Univariate meta-regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | I2 (%) | Coefficient (95% CI) (%) | P-value | |||||

| Region | 0.20 (0.01–0.38) | 0.039 | ||||||

| Western and central Europe and North America | 10 | 28,283 | 1042 | 7.3 (5.4–9.2) | < 0.0001 | 97.0 | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 35 | 5313 | 1105 | 21.1 (16.1–26.1) | < 0.0001 | 98.5 | ||

| Asia and the Pacific | 45 | 7529 | 896 | 12.6 (10.5–14.7) | < 0.0001 | 94.1 | ||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 10 | 1272 | 121 | 13.0 (7.3–18.7) | < 0.0001 | 94.0 | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | 4 | 702 | 43 | 4.7 (0.5–8.8) | < 0.0001 | 88.1 | ||

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | 2 | 119 | 76 | 60.1 (24.1–96.1) | < 0.0001 | 94.4 | ||

| Income level | < 0.0001 | 0.12 (-0.12–0.37) | 0.328 | |||||

| Low income | 16 | 2559 | 460 | 19.7 (13.3–26.1) | < 0.0001 | 96.6 | ||

| Middle income | 76 | 11,559 | 1722 | 14.8 (13.3–16.4) | < 0.0001 | 97.5 | ||

| High income | 14 | 29,100 | 1101 | 7.7 (6.0–9.5) | < 0.0001 | 96.2 | ||

| Patients with diarrhea | < 0.0001 | 0.19 (0.05–0.33) | 0.009 | |||||

| Yes | 34 | 4232 | 625 | 18.2 (14.6–21.7) | < 0.0001 | 97.3 | ||

| Mixed | 66 | 37,517 | 2306 | 11.8 (10.6–13.0) | < 0.0001 | 96.7 | ||

| na | 6 | 1469 | 352 | 29.4 (12.4–46.4) | < 0.0001 | 98.7 | ||

| Total | 106 | 43,218 | 3283 | 14.0 (13.0–15.0) | < 0.0001 | 97.6 | ||

Abbreviations: Yes, patients with diarrhea; Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea; na, not applicable (parameter not provided)

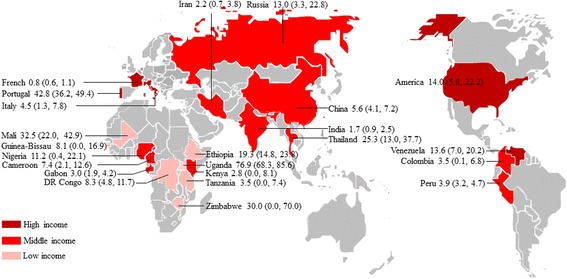

Forty-seven studies reported prevalence of microsporidia (Fig. 1, Table 2), including a total of 18,006 HIV-infected people tested for microsporidia infection. The included studies were conducted in 23 countries (Fig. 4), including 11 countries of sub-Saharan Africa, four of western and central Europe and North America, three of Asia and the Pacific, three of Latin America and the Caribbean, one each of Middle East and North Africa and eastern Europe and central Asia. Of the identified studies, 9 were done in low-income countries, 30 were in middle-income countries, and 9 were in high-income countries (Fig. 4). Forty-five papers were written in English, one each in Chinese and French [17, 24].

Fig. 4.

Map of microsporidia infection in HIV-infected people worldwide. Pooled percentage prevalence and 95% CI are shown for each country

The prevalence of microsporidia infection ranged between 0.7–81.3% (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Meta-analysis by random-effect model indicated that the estimated pooled prevalence of microsporidia infection in people with HIV infection was 11.8% (1090/18,006; 95% CI: 10.1–13.4%) overall, 15.4% (425/3834; 95% CI: 11.1–19.7%) in sub-Saharan Africa, 14.4% (277/8089; 95% CI: 7.8–21.1%) in western and central Europe and North America, 11.7% (251/2791; 95% CI: 8.2–15.1%) in Asia and the Pacific, 5.6% (123/2890; 95% CI: 1.9–9.3%) in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2.2% (8/356; 95% CI: 0.7–3.8%) in the Middle East and North Africa, and 13.0% (6/46; 95% CI: 3.3–22.8%) in eastern Europe and central Asia. Only three studies were done in Latin America and the Caribbean, one each in Middle East and North Africa, and in eastern Europe and central Asia. The prevalence of microsporidia infection in these regions should be interpreted with caution.

Due to the substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 96.7%, P < 0.0001; Table 5), meta-regression analyses indicated that the income level (P = 0.024) and patients with diarrhea (P = 0.004) might be sources of heterogeneity, whereas we detected no significant differences in geographical distribution (P = 0.323). Subgroup analysis showed the pooled prevalence of microsporidia infection in HIV-infected people was significantly higher in low-income countries than in middle-income countries (OR 1.58, 95% CI: 1.08–2.31, P = 0.018), and higher in patients with diarrhea than the control (OR 1.54, 95% CI: 1.14–2.07, P = 0.005).

Table 5.

Pooled prevalence of microsporidia infection in HIV-infected patients

| No. of studies | No. of HIV-infected patients | No. of patients with microsporidia co-infection | Prevalence of microsporidia co-infection (95% CI) (%) | Heterogeneity | Univariate meta-regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | I2 (%) | Coefficient (95% CI) (%) | P-value | |||||

| Region | 0.16 (0.16–0.47) | 0.323 | ||||||

| Western and central Europe and North America | 8 | 8089 | 277 | 14.4 (7.8–21.1) | < 0.0001 | 97.6 | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 17 | 3834 | 425 | 15.4 (11.1–19.7) | < 0.0001 | 96.9 | ||

| Asia and the Pacific | 18 | 2791 | 251 | 11.7 (8.2–15.1) | < 0.0001 | 95.8 | ||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 3 | 2890 | 123 | 5.6 (1.9–9.3) | 0.017 | 75.6 | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | 1 | 356 | 8 | 2.2 (0.7–3.8) | – | – | ||

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | 1 | 46 | 6 | 13.0 (3.3–22.8) | – | – | ||

| Income level | 0.42 (0.06–0.79) | 0.024 | ||||||

| Low income | 9 | 1011 | 219 | 25.2 (13.0–37.4) | < 0.0001 | 97.3 | ||

| Middle income | 30 | 8803 | 580 | 8.4 (6.5–10.3) | <0.0001 | 94.5 | ||

| High income | 9 | 8192 | 291 | 14.4 (8.1–20.6) | < 0.0001 | 97.4 | ||

| Patients with diarrhea | 0.44 (0.15–0.73) | 0.004 | ||||||

| Yes | 17 | 1807 | 396 | 22.2 (14.5–29.9) | < 0.0001 | 96.9 | ||

| Mixed | 28 | 14,573 | 641 | 8.3 (6.5–10.1) | < 0.0001 | 96.3 | ||

| na | 3 | 1626 | 53 | 3.2 (1.7–4.6) | 0.128 | 51.3 | ||

| Total | 48 | 18,006 | 1090 | 11.8 (10.1–13.4) | < 0.0001 | 96.7 | ||

Abbreviations: Yes, patients with diarrhea; Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea; na, not applicable (parameter not provided)

Fifty-eight studies tested 105,922 HIV-infected patients for Isospora infection (Fig. 1, Table 3). The selected studies were done in 20 countries (Fig. 5), including three countries of western and central Europe and North America, eight of sub-Saharan Africa, five of Asia and the Pacific, three of Latin America and the Caribbean, and one of Middle East and North Africa. No studies were found from eastern Europe and central Asia. Of the identified studies, 12 were done in low-income countries, 39 were in middle-income countries, and seven were in high-income countries (Fig. 5). All the included papers were written in English.

Fig. 5.

Map of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people worldwide. Pooled percentage prevalence and 95% CI are shown for each country

The prevalence of Isospora infection ranged between 0.2–26.9% (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Meta-analysis by random-effect model showed that the estimated pooled prevalence of Isospora infection in people with HIV infection was 2.5% (788/105,922; 95% CI: 2.1–2.9%) overall, 6.1% (232/3995; 95% CI: 4.5–7.7%) in sub-Saharan Africa, 0.5% (324/97,721; 95% CI: 0.2–0.8%) in western and central Europe and North America, 7.1% (215/2848; 95% CI: 5.2–9.0%) in Asia and the Pacific, 1.0% (13/922; 95% CI: 0.3–1.7%) in Latin America and the Caribbean, 0.8% (4/436; 95% CI: 0–2.0%) in the Middle East and North Africa. However, few data were available from Latin America, Middle East and North Africa. Only two studies were conducted in Middle East and North Africa, five were done in Latin America and the Caribbean, showing a poor record of Isospora infection in these regions.

With a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89.8%, P < 0.0001; Table 6), meta-regression analyses showed that patients with diarrhea might be sources of heterogeneity (P = 0.005), whereas we detected no significant differences in region distribution (P = 0.143) and income levels (P = 0.806). Subgroup analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people was significantly lower in central Europe and North America than in sub-Saharan Africa (OR 0.40, 95% CI: 0.27–0.59) and in Asia and the Pacific (OR 0.37, 95% CI: 0.26–0.54). Additionally, it was significantly higher in low-income countries (OR 1.94, 95% CI: 1.24–3.04, P = 0.005) and middle-income countries (OR 2.08, 95% CI: 1.41–3.07, P < 0.0001) than in high-income countries. We also found that patients with diarrhea had a higher prevalence of Isospora infection (OR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.14–2.06, P = 0.005).

Table 6.

Pooled prevalence of Isospora infection in HIV-infected patients

| No. of studies | No. of HIV-infected patients | No. of patients with Isospora co-infection | Prevalence of Isospora co-infection (95% CI) (%) | Heterogeneity | Univariate meta-regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | I2 (%) | Coefficient (95% CI) (%) | P-value | |||||

| Region | 0.21 (-0.07–0.49) | 0.143 | ||||||

| Western and central Europe and North America | 6 | 97,721 | 324 | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | < 0.0001 | 92.8 | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 21 | 3995 | 232 | 6.1 (4.5–7.7) | < 0.0001 | 87.0 | ||

| Asia and the Pacific | 24 | 2848 | 215 | 7.1 (5.2–9.0) | < 0.0001 | 83.4 | ||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 5 | 922 | 13 | 1.0 (0.3–1.7) | 0.349 | 10.1 | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | 2 | 436 | 4 | 0.8 (0.0–2.0) | 0.279 | 14.7 | ||

| Income level | -0.04 (-0.38–0.30) | 0.806 | ||||||

| Low income | 12 | 2230 | 93 | 3.8 (2.2–5.5) | < 0.0001 | 91.9 | ||

| Middle income | 39 | 5904 | 366 | 5.8 (4.7–7.0) | < 0.0001 | 86.9 | ||

| High income | 7 | 97,788 | 329 | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | < 0.0001 | 80.0 | ||

| Patients with diarrhea | < 0.0001 | -0.43 (-0.72– -0.13) | 0.005 | |||||

| Yes | 15 | 1271 | 112 | 8.3 (5.7–10.9) | < 0.0001 | 66.1 | ||

| Mixed | 43 | 104,651 | 676 | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | < 0.0001 | 90.4 | ||

| Total | 58 | 105,922 | 788 | 2.5 (2.1–2.9) | < 0.0001 | 89.8 | ||

Abbreviations: Yes, patients with diarrhea; Mixed, including patients with or without diarrhea

We determined the effect of selected studies on the pooled prevalence by excluding single studies sequentially, and found no significant effect of study quality on prevalence of Cryptosporidium and microsporidia infection in HIV-infected people (all P > 0.05), but there was significant effect of study quality on the prevalence of Isospora infection (P = 0.033 and 0.043).

When we excluded the studies by Sorvillo et al. [25], Guiguet et al. [26], and Lagrange-Xelot et al. [27], the pooled prevalence of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people was increased from 2.5% (95% CI: 2.1–2.9%) to 3.0% (95% CI: 2.5–3.5%), 3.3% (95% CI: 2.8–3.8%), and 3.0% (95% CI: 2.5–3.4%), respectively. These findings indicated that the pooled prevalence of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people was substantially influenced by the three studies, and adjusted to 5.0% (469/8570; 95% CI: 4.1–5.9%) by excluding these studies (Additional file 4: Figure S3).

Discussion

Our aim was to estimate the worldwide prevalence of opportunistic intestinal protozoa in people with HIV, showing that Cryptosporidium and microsporidia are the main intestinal protozoa in HIV-infected people, followed by Isospora; their prevalences are usually high in sub-Saharan Africa and in patients with diarrhea, and low in high-income countries. Because of the large proportion of low-income countries and the large number of people with HIV [12], sub-Saharan Africa has a very high burden of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection, reinforcing the importance of routine testing for opportunistic intestinal protozoa in all HIV-infected people. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the global prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people.

Our findings corroborate evidence for a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in Africa and a low prevalence in Europe. In HIV-infected people, a high prevalence has been reported in Uganda (73.6%) [28], Nigeria (79.0%) [29], and South Africa (75.6%) [30] for Cryptosporidium infection; in Zimbabwe (50.9%) [31] and Uganda (76.9%) [28] for microsporidia infection; and in DR Congo (19.6%) [32] and Nigeria (24.3%) [33] for Isospora infection. In contrast, a low prevalence has been shown in France (1.3%) [27], USA (5.4%) [34] and Portugal (7.7%) [35] for Cryptosporidium infection; in France (0.8%) [27] and USA (5.9%) [36] for microsporidia infection; and in France (0.8%) [37] and Italy (0.6%) [38] for Isospora infection.

The incidence of opportunistic intestinal protozoa infection varies, relying on sanitation facilities, drinking contaminated water, animal exposure, CD4 T cell count, ART, diagnostic methods [39, 40]. Thus, the prevalence of infection may vary substantially, even within a country or among different populations of the same region. For example, in the USA, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection is 3.8% in Los Angeles [41], 5.4% in San Francisco [34] and 10.8% in Houston [42]. Large differences of Isospora infection have also been reported in India, with a prevalence of 3.4% in Coimbatore [43], 8.0% in Pune [44] and 25.0% in New Delhi [45]. There are significant differences between different countries for Cryptosporidium (0–78.1%), microsporidia (0.7–81.3%) and Isospora (0.2–26.9%) infection in HIV-infected people. However, limited country-level surveys of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection have been undertaken, making it difficult to compare the infections between regions or populations.

The majority of the studies had additional data on opportunistic intestinal protozoa. Due to the variability of data quality and reporting consistency, we only extracted and analyzed the data on diarrhea, and demonstrated it was related to Cryptosporidium (OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.01–1.46, P = 0.047), microsporidia (OR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.13–2.07, P = 0.007) and Isospora (OR 1.53, 95% CI: 1.14–2.06, P = 0.005) infection in HIV-infected people in comparison with their controls. Moreover, there were some case-control studies that investigated opportunistic intestinal protozoa infection in people with HIV with and without diarrhea. We analyzed the association of diarrhea with Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people. The estimated pooled random effects ORs of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV people with diarrhea compared with their controls were 4.09 (95% CI: 2.32–7.20), 4.72 (95% CI: 3.47–6.42), and 4.93 (95% CI: 3.33–7.29), respectively (Additional files 5, 6 and 7: Figures S4, S5 and S6). These findings show that diarrhea is associated with opportunistic intestinal protozoa infection in HIV people. However, other factors seem to increase the likelihood of infection with opportunistic intestinal protozoa, including CD4 T-lymphocyte counts of less than 100 cells/μl [46], ingestion of contaminated drinking water or food [47], exposure to infected pets or animals [48] and unsafe homosexual activity [49].

There are a few limitations of the present meta-analysis, which may affect the results. First, many relevant studies were identified through our literature search, but not all data were available; there is a possibility that some qualified data were missed. Secondly, the majority of the studies were of moderate or low quality, as most of the data resulted from the conventional microscopic diagnostic techniques; these have a sensitivity which is inferior to polymerase chain reaction, ELISA and direct fluorescent-antibody tests. Additionally, most studies examined a single stool specimen, potentially leading to a false negative result. This means that the reported prevalence was possibly underestimated. Thirdly, the included studies were concentrated in Asia (n = 50), sub-Saharan Africa (n = 45), and western and central Europe and North America (n = 17), Latin America and the Caribbean (n = 12), with few studies from Middle East and North Africa (n = 5), and eastern Europe and central Asia (n = 2), and the study quality was variable, emphasizing the need for more robust surveillance of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people in these regions. Fourthly, different species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium and microsporidia may cause different clinical manifestations in HIV-infected people [40, 50]. However, we did not analyze their distribution characteristics as the microscopic diagnostic techniques in most of the selected studies could not identify the species within the genus Cryptosporidium and microsporidians.

To explain the specific causes of heterogeneity, we did univariate meta-regression analyses on various sources including geographical distribution, income level, and patients with diarrhea, and found different main causes of heterogeneity for the three opportunistic protozoa. These may come from geographical distribution (P = 0.039) and patients with diarrhea (P = 0.009) for Crytosporidium infection, from income level (P = 0.024) and patients with diarrhea (P = 0.004) for microsporidia infection, and from patients with diarrhea (P = 0.005) for Isospora infection. Other potential causes of heterogeneity may include publication year, sample size, and detection methods. Unfortunately, we did not analyze them, as there were not enough data available.

Moreover, we did dummy variable analysis on geographical distribution, income level, and patients with diarrhea. The countries in sub-Saharan Africa had a higher prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Isospora infection in HIV-infected patients than those in western and central Europe and North America, and the low-income countries had a higher prevalence of microsporidia and Isospora infection than the middle or high-income countries. These findings support an association between parasite infection and the income level of countries, which could be due to the fact that people in high-income countries have access to safe water and sanitation facilities, which are responsible for the reduced odds of parasite infection.

Conclusions

The results of our global meta-analysis show a heavy burden of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people, especially in low-income countries and sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, routine screening of opportunistic intestinal protozoa should be done, particularly for those who have CD4 T-lymphocyte count less than 100 cells/μl, and early treatment should be administered. This should include a combination of antibiotics of azithromycin, paramomycin and nitazoxanide for Cryptosporidium infection, albendazole for microsporidia infection, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for Isospora infection [51, 52]. However, antibiotics alone may not necessarily reduce the symptoms associated with opportunistic intestinal protozoa infection [7, 51]. More importantly, it is obligatory to reconstruct the immune system by ART. Additional preventive measures should also emphasize the environmental and personal hygiene, along with the quality of drinking water [47].

Additional files

Checklist of items to include when reporting a meta-analysis. (DOC 69 kb)

Random-effect meta-analysis of microsporidia infection in HIV-infected people. (PDF 267 kb)

Random-effect meta-analysis of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people. (PDF 345 kb)

Random-effect meta-analysis of Isospora infection in HIV-infected people when the three studies affecting the prevalence of Isospora were excluded. (PDF 344 kb)

Random-effect meta-analysis of the association of diarrhea with Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-infected people. (PDF 227 kb)

Fixed-effect meta-analysis of the association of diarrhea with microsporidia infection in HIV-infected people. (PDF 170 kb)

Fixed-effect meta-analysis of the association of diarrhea with Isospora infection in HIV-infected people. (PDF 217 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFD0501300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31672542), the Fundamental Research Funds of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant Nos. Y2016JC05 and 1610312017004) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) (Grant No. CAAS-ASTIP-2014-LVRI-03).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- CI

Confidence interval

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- OR

Odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Authors’ contributions

QL and X-QZ conceived and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript. Z-DW and QL conducted the study. H-HL, SL, LZ and Y-KZ collected and analyzed the data. Z-DW and QL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-017-2558-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ze-Dong Wang, Email: 851077608@qq.com.

Quan Liu, Email: liuquan1973@hotmail.com.

Huan-Huan Liu, Email: lhh1211291518@163.com.

Shuang Li, Email: 18704493241@163.com.

Li Zhang, Email: 913710993@qq.com.

Yong-Kun Zhao, Email: zhaoyongkun1976@126.com.

Xing-Quan Zhu, Email: xingquanzhu1@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Miao YM, Gazzard BG. Management of protozoal diarrhoea in HIV disease. HIV Med. 2000;1:194–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2000.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan C, Beadsworth MB, Beeching NJ. HIV and diarrhoea: what is new? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29:486–494. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimelis T, Tassachew Y, Lambiyo T. Cryptosporidium and other intestinal parasitic infections among HIV patients in southern Ethiopia: significance of improved HIV-related care. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:270. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1554-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iribarren JA, Rubio R, Aguirrebengoa K, Arribas JR, Baraia-Etxaburu J, Gutierrez F, et al. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections and other coinfections in HIV-infected patients: may 2015. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2016;34:516.e1–516.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodgame RW. Understanding intestinal spore-forming protozoa: Cryptosporidia, microsporidia, isospora, and cyclospora. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:429–441. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mbae C, Mulinge E, Waruru A, Ngugi B, Wainaina J, Kariuki S. Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium in children in an urban informal settlement of Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcos LA, Gotuzzo E. Intestinal protozoan infections in the immunocompromised host. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:295–301. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283630be3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanduja S, Ghoshal U, Agarwal V, Pant P, Ghoshal UC. Identification and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi among human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, et al. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:557–563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02758-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taye B, Desta K, Ejigu S, Dori GU. The magnitude and risk factors of intestinal parasitic infection in relation to human immunodeficiency virus infection and immune status, at ALERT hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Parasitol Int. 2014;63:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pape JW, Johnson WD., Jr Isospora belli infections. Prog Clin Parasitol. 1991;2:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZD, Wang SC, Liu HH, Ma HY, Li ZY, Wei F, et al. Prevalence and burden of Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e177–ee88. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao L, Zhang L, Jin Q. Meta-analysis: prevalence of HIV infection and syphilis among MSM in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:354–358. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang XL, Chen SY, Gao K, Mai HX, Han ZG, Xu HF, et al. Seroepidemiological analysis of opportunistic protozoal infections in patients with HIV/AIDS infection. J Trop Med. 2015;15:1425–1428. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie RH, Chen GX, Ou Yang SS. Intestinal parasitic infection in HIV/AIDS patients in Hengyang region. Chin J Immunol. 2015;31:695–697. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang XF, Jiang ZH, Yu BX, Zhou DS, Lin Y, Tang WX. A preliminary study on the infection and genotype of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV/AIDS patients in Guangxi. Chin J Schistosomiasis Control. 2016;28:550–553. doi: 10.16250/j.32.1374.2016038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu LY, Xu YH, Ma BY, Zhang Y, Nie SF. Study on survival and related factors of AIDS cases among blood donors. Chin J AIDS Std. 2007;13:512–514. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, He YQ, Jiao BX, Hua WH, Zhou R, Wang YG, et al. Analysis of Cryptosporidium infection in 149 HIV/AIDS patients with chronic diarrhea. Chin J Dermatovenereol. 2011;25:868–870. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Liu Y, Wang HZ, Li J, Jiao BX. Investigation of Cryptosporidium infection in HIV patients with chronic diarrhea. Chin J Public Health. 2012;28:1099–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian LG, Chen GJ, Chen JX, Cai YC, Guo J, Tong XM, et al. Investigation of intestinal parasitic infection in high prevalence areas of HIV/AIDS in rural areas of China HIV/AIDS high prevalence areas in rural China. Chin J Schistosomiasis Control. 2012;24:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang HZ, Hua WH, Li M, Tian JH, Zhang Y, Wang YG, et al. Detection of pathogenic microorganisms in stool samples from 253 HIV patients with chronic diarrhea. Chin J Exp Clin Infect Dis. 2012;6:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maiga I, Doumbo O, Dembele M, Traore H, Desportes-Livage I, Hilmarsdottir I, et al. Human intestinal microsporidiosis in Bamako (Mali): the presence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in HIV seropositive patients. Sante. 1997;7:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorvillo FJ, Lieb LE, Seidel J, Kerndt P, Turner J, Ash LR. Epidemiology of isosporiasis among persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Los Angeles County. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:656–659. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keshinro IB, Musa BO. Cellular immunity and diarrhoeal disease amongst patients infected with the human immunodeficiency viruses 1 and 2 in Zaria, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2003;12:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagrange-Xelot M, Porcher R, Sarfati C, de Castro N, Carel O, Magnier JD, et al. Isosporiasis in patients with HIV infection in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era in France. HIV Med. 2008;9:126–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumwine JK, Kekitiinwa A, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Ndeezi G, Downing R, Feng X, et al. Cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis in Ugandan children with persistent diarrhea with and without concurrent infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:921–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adesiji YO, Lawal RO, Taiwo SS, Fayemiwo SA, Adeyeba OA. Cryptosporidiosis in HIV infected patients with diarrhoea in Osun state southwestern Nigeria. Eur J Gen Med. 2007;4:119–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartelt LA, Dillingham R, Sevilleja JE, Barrett LJ, Guerrant RL, Bessong PO, et al. High Cryptosporidium parvum anti-IgG seroprevalance among HIV-positive adults in Limpopo and other regions of South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:235–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Gumbo T, Sarbah S, Gangaidzo IT, Ortega Y, Sterling CR, Carville A, et al. Intestinal parasites in patients with diarrhea and human immunodeficiency virus infection in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 1999;13:819–821. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry MC, De Clercq D, Lokombe B, Kayembe K, Kapita B, Mamba K, et al. Parasitological observations of chronic diarrhoea in suspected AIDS adult patients in Kinshasa (Zaire) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:309–310. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nwuba CO, Okonkwo R, Abolarin O, Ogbu N, Modebelu P. Disparities in the prevalence of AIDS related opportunistic infections in Nigeria - implications for initiating prophylaxis based on absolute CD4 count. Retrovirology. 2012;9(Suppl. 1):147. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colford JM, Jr, Tager IB, Hirozawa AM, Lemp GF, Aragon T, Petersen C. Cryptosporidiosis among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Factors related to symptomatic infection and survival. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:807–816. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matos O, Tomas A, Aguiar P, Casemore D, Antunes F. Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients with diarrhoea in Santa Maria hospital, Lisbon. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 1998;45:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anwar-Bruni DM, Hogan SE, Schwartz DA, Wilcox CM, Bryan RT, Lennox JL. Atovaquone is effective treatment for the symptoms of gastrointestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 1996;10:619–623. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rene E, Marche C, Regnier B, Saimot AG, Vilde JL, Perrone C, et al. Intestinal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A prospective study in 132 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:773–780. doi: 10.1007/BF01540353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandonisio O, Maggi P, Panaro MA, Lisi S, Andriola A, Acquafredda A, et al. Intestinal protozoa in HIV-infected patients in Apulia, South Italy. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123:457–462. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899003015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nsagha DS, Njunda AL, Assob NJ, Ayima CW, Tanue EA, Kibu OD, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in relation to CD4(+) T cell counts and diarrhea in HIV/AIDS patients with or without antiretroviral therapy in Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cama VA, Ross JM, Crawford S, Kawai V, Chavez-Valdez R, Vargas D, et al. Differences in clinical manifestations among Cryptosporidium species and subtypes in HIV-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:684–691. doi: 10.1086/519842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sorvillo FJ, Lieb LE, Kerndt PR, Ash LR. Epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis among persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Los Angeles County. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:326–331. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathewson JJ, Salameh BM, DuPont HL, Jiang ZD, Nelson AC, Arduino R, et al. HEp-2 cell-adherent Escherichia coli and intestinal secretory immune response to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in outpatients with HIV-associated diarrhea. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:87–90. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.1.87-90.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayalakshmi J, Appalaraju B, Mahadevan K. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunoassay for the detection of Cryptosporidium antigen in fecal specimens of HIV/AIDS patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:137–138. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.40427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni SV, Kairon R, Sane SS, Padmawar PS, Kale VA, Thakar MR, et al. Opportunistic parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients presenting with diarrhoea by the level of immunesuppression. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta K, Bala M, Deb M, Muralidhar S, Sharma DK. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-infected individuals and their relationship with immune status. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:161–165. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.115247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izadi M, Jonaidi-Jafari N, Saburi A, Eyni H, Rezaiemanesh MR, Ranjbar R. Prevalence, molecular characteristics and risk factors for cryptosporidiosis among Iranian immunocompromised patients. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56:836–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speich B, Croll D, Furst T, Utzinger J, Keiser J. Effect of sanitation and water treatment on intestinal protozoa infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:87–99. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dwivedi KK, Prasad G, Saini S, Mahajan S, Lal S, Baveja UK. Enteric opportunistic parasites among HIV infected individuals: associated risk factors and immune status. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caputo C, Forbes A, Frost F, Sinclair MI, Kunde TR, Hoy JF, et al. Determinants of antibodies to Cryptosporidium infection among gay and bisexual men with HIV infection. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:291–297. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chabchoub N, Abdelmalek R, Mellouli F, Kanoun F, Thellier M, Bouratbine A, et al. Genetic identification of intestinal microsporidia species in immunocompromised patients in Tunisia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gruz F, Fuxman C, Errea A, Tokumoto M, Fernandez A, Velasquez J, et al. Isospora belli infection after isolated intestinal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H, et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connolly GM, Forbes A, Gazzard BG. Investigation of seemingly pathogen-negative diarrhoea in patients infected with HIV1. Gut. 1990;31:886–889. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.8.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandonisio O, Maggi P, Panaro MA, Bramante LA, Di Coste A, Angarano G. Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients with diarrhoeal illness. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:190–194. doi: 10.1007/BF00158790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cama V, Gilman RH, Vivar A, Ticona E, Ortega Y, Bern C, et al. Mixed Cryptosporidium infections and HIV. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1025–1028. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.060015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colebunders R, Lusakumuni K, Nelson AM, Gigase P, Lebughe I, van Marck E, et al. Persistent diarrhoea in Zairian AIDS patients: an endoscopic and histological study. Gut. 1988;29:1687–1691. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.12.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Therizol-Ferly PM, Tagliante-Saracino J, Kone M, Konan A, Ouhon J, Assoumou A, et al. Chronic diarrhea and parasitoses in adults suspected of AIDS in the Ivory Coast. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1989;82:690–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hunter G, Bagshawe AF, Baboo KS, Luke R, Prociv P. Intestinal parasites in Zambian patients with AIDS. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:543–545. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90102-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Assoumou A, Kone M, Penali LK, Coulibaly M, N'Draman AA. Cryptosporidiosis and HIV in Abidjan (Ivory Coast). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86:85–6. [PubMed]

- 60.Dieng T, Ndir O, Diallo S, Coll-Seck AM, Dieng Y. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium sp. and Isospora belli in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Dakar (Senegal) Dakar Med. 1994;39:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chintu C, Luo C, Baboo S, Khumalo-Ngwenya B, Mathewson J, DuPont HL, et al. Intestinal parasites in HIV-seropositive Zambian children with diarrhoea. J Trop Pediatr. 1995;41:149–152. doi: 10.1093/tropej/41.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mwachari C, Batchelor BI, Paul J, Waiyaki PG, Gilks CF. Chronic diarrhoea among HIV-infected adult patients in Nairobi, Kenya. J Inf Secur. 1998;37:48–53. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(98)90561-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fisseha B, Petros B, Woldemichael T, Mohammed H. Diarrhoea-associated parasitic infectious agent in AIDS patients with selected Addis Ababa hospitals. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1999;13:169–73. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cegielski JP, Ortega YR, McKee S, Madden JF, Gaido L, Schwartz DA, et al. Cryptosporidium, Enterocytozoon, and Cyclospora infections in pediatric and adult patients with diarrhea in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:314–321. doi: 10.1086/515131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lebbad M, Norrgren H, Naucler A, Dias F, Andersson S, Linder E. Intestinal parasites in HIV-2 associated AIDS cases with chronic diarrhoea in Guinea-Bissau. Acta Trop. 2001;80:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nwokediuko SC, Bojuwoye BJ, Onyenekwe B. Apparent rarity of cryptosporidiosis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related diarrhoea in Enugu, south-eastern, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2002;9:70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adjei A, Lartey M, Adiku TK, Rodrigues O, Renner L, Sifah E, et al. Cryptosporidium oocysts in Ghanaian AIDS patients with diarrhoea. East Afr Med J. 2003;80:369–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Tadesse A, Kassu A. Intestinal parasite isolates in AIDS patients with chronic diarrhea in Gondar teaching hospital, north west Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2005;43:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sarfati C, Bourgeois A, Menotti J, Liegeois F, Moyou-Somo R, Delaporte E, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites including microsporidia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:162–4. [PubMed]

- 70.Mariam ZT, Abebe G, Mulu A. Opportunistic and other intestinal parasitic infections in AIDS patients, HIV seropositive healthy carriers and HIV seronegative individuals in southwest Ethiopia. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blanco MA, Iborra A, Vargas A, Nsie E, Mba L, Fuentes I. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans in Equatorial Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1282–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooke ML, Goddard EA, Brown RA. Endoscopy findings in HIV-infected children from sub-Saharan Africa. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55:238–243. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Babatunde SK, Salami AK, Fabiyi JP, Agbede OO, Desalu OO. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation in HIV seropositive and seronegative patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9:123–128. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.68356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alemu A, Shiferaw Y, Getnet G, Yalew A, Addis Z. Opportunistic and other intestinal parasites among HIV/AIDS patients attending Gambi higher clinic in Bahir Dar city, north West Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:661–665. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roka M, Goni P, Rubio E, Clavel A. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in HIV-positive patients on the island of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea: its relation to sanitary conditions and socioeconomic factors. Sci Total Environ. 2012;432:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wumba R, Jean M, Benjamin LM, Madone M, Fabien K, Josué Z, et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi identification using real-time polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism in HIV-infected humans from Kinshasa province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Parasitol Res. 2012;2012:278028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Girma M, Teshome W, Petros B, Endeshaw T. Cryptosporidiosis and isosporiasis among HIV-positive individuals in south Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Samie A, Makuwa S, Mtshali S, Potgieter N, Thekisoe O, Mbati P, et al. Parasitic infection among HIV/AIDS patients at Bela-Bela clinic, Limpopo province, South Africa with special reference to Cryptosporidium. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45:783–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vouking MZ, Enoka P, Tamo CV, Tadenfok CN. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among HIV patients at the Yaounde central hospital, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:136. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.136.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bissong MEA, Nguemain NF, Ng'awono TEN, Kamga FHL. Burden of intestinal parasites amongst HIV/AIDS patients attending Bamenda regional Hospital in Cameroon. Afr J Cln Exper Microbiol. 2015;16:97. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kiros H, Nibret E, Munshea A, Kerisew B, Adal M. Prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections among individuals living with HIV/AIDS at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;35:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ojuromi OT, Duan L, Izquierdo F, Fenoy SM, Oyibo WA, Del Aguila C, et al. Genotypes of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Lagos, Nigeria. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2016;63:414–418. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamel AG, Maning N, Arulmainathan S, Murad S, Nasuruddin A, Lai KP. Cryptosporidiosis among HIV positive intravenous drug users in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1994;25:650–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moolasart P, Eampokalap B, Ratanasrithong M, Kanthasing P, Tansupaswaskul S, Tanchanpong C. Cryptosporidiosis in HIV infected patients in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1995;26:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anand L, Brajachand NG, Dhanachand CH. Cryptosporidiosis in HIV infection. J Commun Dis. 1996;28:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Punpoowong B, Viriyavejakul P, Riganti M, Pongponaratn E, Chaisri U, Maneerat Y. Opportunistic protozoa in stool samples from HIV-infected patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wanachiwanawin D, Manatsathit S, Lertlaituan P, Thakerngpol K, Suwanagool P. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV and non-HIV infected patients with chronic diarrhea in Thailand. Siriraj Hosp Gaz. 1999;51:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prasad KN, Nag VL, Dhole TN, Ayyagari A. Identification of enteric pathogens in HIV-positive patients with diarrhoea in northern India. J Health Popul Nut. 2000;18:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wiwanitkit V. Intestinal parasitic infections in Thai HIV-infected patients with different immunity status. BMC Gastroenterol. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chokephaibulkit K, Wanachiwanawin D, Tosasuk K, Pavitpok J, Vanprapar N, Chearskul S. Intestinal parasitic infections among human immunodeficiency virus-infected and -uninfected children hospitalized with diarrhea in Bangkok, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:770–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Waywa D, Kongkriengdaj S, Chaidatch S, Tiengrim S, Kowadisaiburana B, Chaikachonpat S, et al. Protozoan enteric infection in AIDS related diarrhea in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32(Suppl. 2):151–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kumar SS, Ananthan S, Lakshmi P. Intestinal parasitic infection in HIV-infected patients with diarrhoea in Chennai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mohandas. Sehgal R, Sud A, Malla N. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic pathogens in HIV-seropositive individuals in northern India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lim YA, Rohela M, Sim BL, Jamaiah I, Nurbayah M. Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients in Kajang hospital, Selangor. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(Suppl. 4):30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guk SM, Seo M, Park YK, Oh MD, Choe KW, Kim JL, et al. Parasitic infections in HIV-infected patients who visited Seoul National University Hospital during the period 1995–2003. Korean J Parasitol. 2005;43:1–5. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chhin S, Harwell JI, Bell JD, Rozycki G, Ellman T, Barnett JM, et al. Etiology of chronic diarrhea in antiretroviral-naive patients with HIV infection admitted to Norodom Sihanouk hospital, Phnom Penh. Cambodia Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:925–932. doi: 10.1086/507531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ramakrishnan K, Shenbagarathai R, Uma A, Kavitha K, Rajendran R. Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation in HIV/AIDS patients with diarrhea in Madurai City, South India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:209–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stark D, Fotedar R, Van Hal S, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis JT, et al. Prevalence of enteric protozoa in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men from Sydney. Australia Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saldanha D, Gupta N, Shenoy S, Saralaya V. Prevalence of opportunistic infections in AIDS patients in Mangalore, Karnataka. Trop Dr. 2008;38:172–173. doi: 10.1258/td.2007.070171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Viriyavejakul P, Nintasen R, Punsawad C, Chaisri U, Punpoowong B, Riganti M. High prevalence of Microsporidium infection in HIV-infected patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saksirisampant W, Prownebon J, Saksirisampant P, Mungthin M, Siripatanapipong S, Leelayoova S. Intestinal parasitic infections: prevalences in HIV/AIDS patients in a Thai AIDS-care centre. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;103:573–581. doi: 10.1179/000349809X12502035776072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tian LG, Chen JX, Wang TP, Cheng GJ, Steinmann P, Wang FF, et al. Co-infection of HIV and intestinal parasites in rural area of China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]