Abstract

Purpose

Depression during pregnancy is highly prevalent and is associated with increased risk of a variety of negative psychological and medical outcomes in both mothers and offspring. Antenatal depression often co-occurs with significant anxiety, potentially exacerbating morbidities for women and their children. However, screening during the antenatal period is frequently limited to assessment of depression, so that other significant co-morbid disorders may be missed. Follow-up assessment by clinicians has similarly focused primarily on detection of depressive symptoms. Anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder, among others, often go undetected in perinatal care settings, even when depression is identified. Failing to recognize these comorbid diagnoses may lead to inadequate treatment or only partial alleviation of distress. Consequently, screening for and assessment of comorbid disorders is warranted.

Method

In this study, 382 pregnant women (M age = 25.8 [SD = 5.3] years, 85.0% Caucasian) receiving care at a university hospital clinic and Maternal Mental Health Care centers in eastern Iowa and who screened positive for depression on the Beck Depression Inventory completed the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV to assess comorbid mental health symptoms and diagnoses.

Results

Overall, findings demonstrate high rates of anxiety disorders among women both with and without current major depression, although depressed women reported higher rates of generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Notably, however, incidence specific symptoms were comparable across groups.

Conclusions

Routine screening of both anxiety and depression during pregnancy should be conducted.

Keywords: Antenatal Depression, Anxiety, Beck Depression Inventory, Perinatal Mental Health

Introduction

Antenatal depression is highly prevalent, with an estimated 6–13% of women experiencing depression during pregnancy (Bennett et al. 2004; Gavin et al. 2005). Indeed, the prevalence of both depressive and anxiety symptoms may be elevated during pregnancy compared to the postpartum period (Evans et al. 2001; Heron et al. 2004). Although a substantial proportion of women experience mental health difficulties during pregnancy, only a fraction receive mental health treatment (Andersson et al. 2003; Bonari et al. 2004; Goodman & Tyler-Viola 2010), suggesting significant gaps in current screening and assessment procedures.

Recognition of antenatal depression in clinical settings is of particular significance due to implications for functional impairment, both during and after pregnancy. Research has demonstrated an association between mothers’ mood difficulties and adverse neonatal and obstetrical outcomes (Bonari et al. 2004), supporting the longer-term benefits and consequences of early identification and intervention for mothers experiencing depression during pregnancy (Siu et al. 2016). Antenatal depression is also a significant predictor of postnatal depression (Heron et al. 2004; Leigh & Milgrom 2008). Mood difficulties during pregnancy, particularly in conjunction with co-occurring psychopathology, are likely to exacerbate potential negative outcomes in the postpartum period.

Screening procedures have been increasingly implemented in clinical settings (Breedlove & Fryzelka 2011), as evidenced by the recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation to implement depression screening during and after pregnancy (Siu et al., 2016). These screening tools often include the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al 1987) and the two-item screen developed by Whooley et al (Whooley et al 1997). However, assessment has been limited largely to symptoms of depression. Initial screening typically involves administration of a brief symptom checklist to assess basic depressive symptoms (Breedlove & Fryzelka 2011), or some providers are trained to verbally ask patients two primary questions as a depression screen: “Are you down, depressed, or blue?” and “Have you lost interest or pleasure in things?” reflecting primary symptoms of a major depressive episode (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Clinical assessment following positive depression screens is unclear; however, unless administered by mental health professionals, follow-up assessment is most likely limited to further evaluation of core depressive symptoms.

While more widespread implementation of depression screening represents a clear improvement in care, more thorough follow-up assessment of women who screen positive for depression during pregnancy may be needed (Breedlove & Fryzelka 2011). Specifically, current screening procedures neglect assessment of comorbid diagnoses likely to influence clinical treatment and outcome. Women who initially screen positive for depression but do not meet the standard for a positive clinical assessment by providing affirmative responses to typical follow-up questions specifically querying primary depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling down or depressed, anedonia) are unlikely to be assessed further for symptoms of other conditions, such as anxiety disorders. These women are therefore unlikely to be referred for further evaluation or treatment because symptoms of additional diagnoses are not included in basic clinical screening and assessment procedures.

Other diagnoses, such as anxiety disorders, are also likely of significance during pregnancy. Prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy has been estimated at approximately 6.6% (Andersson et al. 2003), while reported estimates of significant anxiety symptoms are higher (e.g., 15.6%; Rubertsson et al. 2014). Symptoms of depression and anxiety are highly correlated during antepartum (e.g., Lancaster et al. 2010; Leigh & Milgrom 2008). However, anxiety frequently goes undetected and untreated in obstetrical settings (Coleman et al. 2008; Goodman & Tyler-Viola 2010), and little is known regarding symptomatic presentation of anxiety in pregnant women who are depressed or screen positive for depression.

Antenatal anxiety predicts offspring psychological difficulties in both infancy and childhood (Van den Bergh et al. 2005), indicating the importance of this issue for both mothers and their children. Antenatal anxiety predicts later development of postpartum depression (Heron et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2007; Robertson et al. 2004), even after accounting for psychosocial vulnerability and antenatal depression (Coelho et al. 2011; Sutter-Dallay et al. 2004). The existing risk presented by antenatal anxiety suggests that clinical screening should include evaluation of both depression and anxiety both during pregnancy and in the postpartum (Andersson et al. 2003; Heron et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2007; Matthey et al. 2003; Stuart et al., 1998).

Because of this increasing emphasis on screening for comorbidity during pregnancy, we re-examined data we had available from a large-scale project in which our original goal was to study only depression screening. This paper reports new analyses of the comorbidity of GAD, OCD, PD, and PTSD and incidence of specific symptoms of each of these disorders in a large sample of pregnant women to provide comparative symptom profiles among women with and without current major depressive episode and to better approximate patient presentations in general care settings.

Method

Participants and Procedure

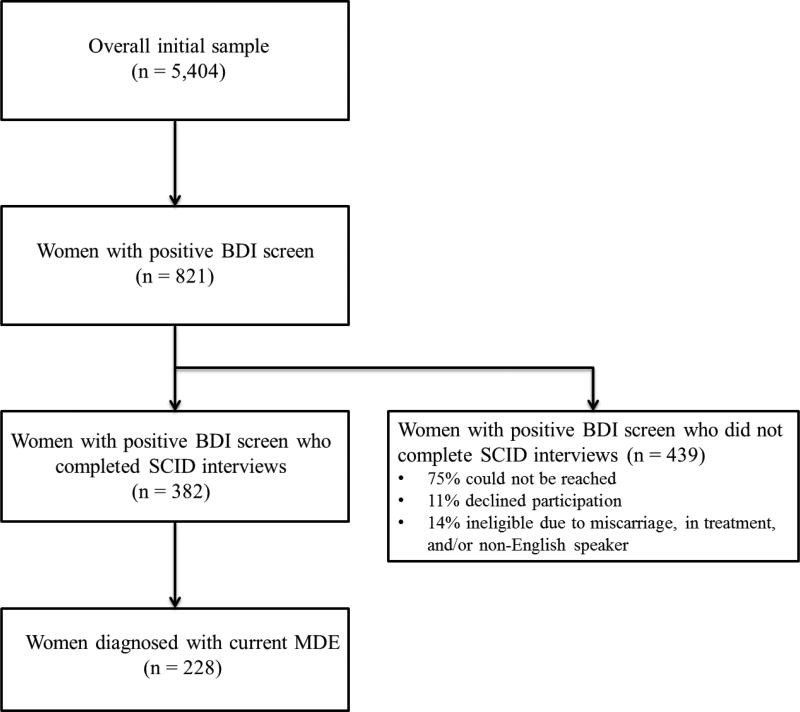

Women between 6 and 28 weeks of pregnancy presenting to a university hospital OB-GYN clinic or one of six Maternal Health Care Centers in Eastern Iowa completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; N = 5,404; Figure 1) between 2000–2004. Participants recruited from Maternal Health Care Centers were younger, reported lower income and education, were more likely to be unemployed, single or living without a partner, and had more premature births, stillbirths, and miscarriages compared to participants recruited from the university hospital OB-GYN clinic (Koleva et al. 2011). Our previous analyses of this screening data (Koleva et al., 2011; Koleva and Stuart, 2014) examined psychosocial risk factors for depression during pregnancy, but did not examine depression comorbidity. Our clinical experience since the publication of those papers examining risk for depression suggest that comorbidity is often unassessed and is critical to evaluate since it impacts both treatment planning and prognosis. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study participation.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart

The 821 women in our study who screened positive for depression on the BDI were subsequently interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID; Spitzer et al. 1992). Participant flow through each stage of the study is depicted in Figure 1. Women completing the interviews did not differ from those who did not on mean BDI scores (mean BDI = 21.28 and 22.08, respectively; p = .071) or marital status (59.2% and 57.5% married or living with partner, respectively; p = .637), though non-participants were more likely to be unemployed (62.4% versus 49.7%, respectively; p < .001), less educated (44.6% versus 54.1% with 13 years education or greater; p = .007), and to be from a minority group (24.4% versus 15%, respectively; p = .001).

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck et al. 1961)

The BDI is a commonly used 21-item self-report inventory used to measure severity of depression. Each question consists of four statements describing increasing intensities of symptoms of depression. Items are rated on a scale of 0–3, reflecting how participants have felt over the last week. Total scores range from 0–48 with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptomatology. Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was satisfactory (N = 382; α = .68).

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (The SCID-IV; Spitzer et al. 1992)

The SCID-IV is a semi-structured diagnostic interview to assess DSM-IV disorders. Good estimates of validity and reliability for the SCID-IV have been reported in youth and adult administrations of this test (Spitzer et al. 1992), and it has demonstrated good clinical utility in controlled outcome studies (e.g., Azrin et al. 2001).

For all diagnoses symptoms are coded as present, subthreshold, or absent. In this study, the current Major Depressive Episode module was completed in full for all women regardless of response to the entry items (sad, depressed mood and/or loss of interest). All other modules were completed in full only if the screener item(s) were endorsed to reduce participant burden.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed to examine the frequency of comorbid anxiety disorders as well as specific anxiety symptoms in the full sample of women with positive screens on the BDI and subsamples of women with and without current MDE. Additionally, Pearson’s Chi-square statistics were computed to compare frequency of symptoms across depressed and non-depressed subsamples. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (Version 23).

Results

Descriptive and demographic statistics are presented in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 18.1 to 43.1 years (M = 25.8, SD = 5.3) and reported an average of 13.4 years of education. A majority of participants self-identified as Caucasian (85.0%), were married or living with a romantic partner (59.2%), employed (50.3%), and reported annual family incomes of $20,000 or less (57.3%). A significantly higher proportion of currently depressed women also met criteria for GAD (p < .001) and PTSD (p = .026). Differences in presentation of depressive symptoms between women with and without current MDE are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive and Demographic Statistics

| Full Sample | Subsample with Current MDE |

Subsample without Current MDE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 382 | N = 228 | N = 154 | p | |

| Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | ||

| Age | 25.8 (5.3) | 25.9 (5.2) | 25.6 (5.4) | .604 |

| Caucasian Ethnicity | 85.0 | 85.9 | 83.7 | .548 |

| Years Education | 13.4 (2.2) | 13.3 (2.3) | 13.5 (2.2) | .473 |

| Income < 20,000 | 57.3 | 61.3 | 50.9 | .079 |

| Employed | 50.3 | 44.7 | 58.6 | .008 |

| Married or Living with Partner | 59.2 | 59.6 | 58.4 | .814 |

| Week of Pregnancy at Assessment | 14.4 (5.1) | 14.5 (5.2) | 14.2 (5.0) | .472 |

| Number of Children | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.16 (1.3) | 0.7 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Psychiatric Treatment History | ||||

| Psychiatric Medication | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Past MDE | 56.7 | 60.8 | 51.0 | .068 |

| GAD | 14.2 | 20.5 | 4.7 | <.001 |

| Panic Disorder | 5.1 | 6.3 | 3.3 | .201 |

| OCD | 3.5 | 4.9 | 1.3 | .127 |

| PTSD | 5.1 | 7.1 | 2.0 | .026 |

Note. MDE = Major Depressive Episode diagnosed on SCID. GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder. OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. PTSD = Post-Traumatic Distress Disorder.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Endorsed SCID Current Depressive Symptoms among Pregnant Women with and without Current MDE

| Women with Current MDE |

Women Without Current MDE |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 228 | N = 154 | ||

| % Endorsed | p | ||

| Depressed Mood | 68.9 | 7.8 | <.001 |

| Anhedonia | 82.5 | 11.2 | <.001 |

| Appetite/Weight Loss | 77.4 | 43.7 | <.001 |

| Appetite/Weight Gain | 19.0 | 21.9 | .502 |

| Insomnia | 79.6 | 57.0 | <.001 |

| Hypersomnia | 28.1 | 25.2 | .526 |

| Psychomotor Agitation | 44.9 | 26.0 | <.001 |

| Psychomotor Retardation | 50.4 | 26.9 | <.001 |

| Fatigue | 89.5 | 48.7 | <.001 |

| Worthlessness | 66.7 | 23.8 | <.001 |

| Guilt | 71.4 | 35.4 | <.001 |

| Concentration difficulties | 63.6 | 39.6 | <.001 |

| Indecisiveness | 54.4 | 22.1 | <.001 |

| Thoughts of Own Death | 28.6 | 6.6 | <.001 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 8.8 | 2.0 | .007 |

| Suicide Plan | 4.8 | 0.7 | .023 |

| Suicide Attempt | 0.9 | 0 | .247 |

Note. MDE = Major Depressive Episode diagnosed on SCID.

Anxiety Disorder Symptoms

General Anxiety Disorder

Frequencies of endorsed GAD symptoms are shown in Table 3. Significantly more women reported symptoms of nervousness or anxiety (p = .002), excessive anxiety or worry (p = .015), being easily fatigued (p = .046), sleep disturbance (p = .001), and distress or impairment on these symptoms (p < .001). Notably, 22.0% of women not meeting full criteria for current MDE also endorsed experiencing nervousness or anxiety; of these, a majority reported experiencing these same symptoms of GAD (range: 50.0% to 66.7%), with the exception of distress or impairment from the symptoms, which was still endorsed by 38.1% of these women.

Table 3.

Frequencies of Endorsed SCID GAD and Panic Disorder Symptoms

| Full Sample | With MDE | Without MDE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 382 | N = 228 | N = 154 | ||

| % Endorsed | p | |||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | ||||

| Entry Item: Nervous/Anxious | 31.3 | 37.5 | 22.0 | .002 |

| Excessive Anxiety/Worry | 67.7 | 74.2 | 51.4 | .015 |

| Difficulty Controlling Worry | 65.5 | 69.9 | 53.3 | .102 |

| Restless, Keyed Up, On Edge | 64.7 | 69.2 | 50.0 | .116 |

| Easily Fatigued | 77.6 | 82.8 | 61.9 | .046 |

| Difficulty Concentrating | 62.8 | 66.2 | 52.4 | .256 |

| Irritability | 79.1 | 83.1 | 66.7 | .108 |

| Muscle Tension | 62.8 | 66.2 | 52.4 | .256 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 80.0 | 87.7 | 55.0 | .001 |

| Distress/Impairment | 73.3 | 84.6 | 38.1 | <.001 |

| Panic Disorder | ||||

| Entry Item: Past month panic attack | 17.4 | 21.0 | 12.0 | .025 |

| Recurrent unexpected panic | 48.6 | 47.1 | 52.6 | .678 |

| Worry about implications of attack/change in behavior related to attacks | 36.2 | 34.9 | 40.0 | .723 |

| Symptoms develop abruptly, peak within 10 minutes | 74.0 | 75.0 | 71.4 | .796 |

| Heart palpitations | 70.2 | 74.3 | 58.3 | .297 |

| Sweating | 34.0 | 37.1 | 25.0 | .444 |

| Trembling/shaking | 43.5 | 42.9 | 45.5 | .880 |

| Shortness of breath | 55.3 | 60.0 | 41.7 | .270 |

| Feeling of choking | 10.9 | 14.7 | 0 | .159 |

| Chest pain or discomfort | 37.0 | 41.2 | 25.0 | .318 |

| Nausea or abdominal distress | 23.9 | 26.5 | 16.7 | .494 |

| Dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, faint | 50.0 | 52.9 | 41.7 | .502 |

| Derealization/depersonalization | 21.7 | 23.5 | 16.7 | .620 |

| Fear of losing control or going crazy | 30.4 | 32.4 | 25.0 | .634 |

| Fear of dying | 28.3 | 26.5 | 33.3 | .650 |

| Parathesias | 21.7 | 29.4 | 0 | .034 |

| Chills or hot flushes | 66.7 | 75.8 | 41.7 | .032 |

Note. MDE = Major Depressive Episode diagnosed on SCID. GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Panic Disorder

More depressed women reported having experienced a panic attack in the past month compared to non-depressed women (p = .025). Endorsement of PD symptoms was comparable across groups, with two exceptions: a significantly higher proportion of women reported experiencing parathesias (p = .034) and chills or hot flushes (p = .032) in connection with a panic attack in the past month. Although fewer women without current MDE endorsed symptoms of panic, a noteworthy proportion of those who endorsed the entry item reported individual panic symptoms (see Table 3).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Significantly more depressed women reported having experiences obsessions and/or compulsions over the previous month (p < .001). However, rates of endorsement were comparable across groups for all other individual OCD symptoms (all p > .258; see Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequencies of Endorsed SCID OCD and PTSD Symptoms

| Full Sample | With MDE | Without MDE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 382 | N = 228 | N = 154 | ||

| % Endorsed | p | |||

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | ||||

| Entry Item: Obsessions/compulsions | 22.5 | 28.6 | 13.4 | <.001 |

| Intrusive thoughts, images, impulses | 39.7 | 43.1 | 29.4 | .317 |

| More than worries | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.3 | .983 |

| Efforts to ignore/suppress/neutralize | 31.6 | 31.7 | 31.3 | .973 |

| Recognized as product of own mind | 43.6 | 43.9 | 42.9 | .946 |

| Compulsions are repetitive behaviors | 58.3 | 62.3 | 47.4 | .258 |

| Compulsions aimed at reducing distress or preventing events | 40.0 | 41.2 | 36.8 | .742 |

| Recognized as excessive or unreasonable | 61.2 | 62.5 | 57.9 | .727 |

| Cause marked distress, time-consuming, significantly interfere | 26.5 | 29.2 | 20.0 | .435 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | ||||

| Entry Item: Nightmares/flashbacks/intrusive thoughts | 16.6 | 19.6 | 12.0 | .051 |

| Experienced event involving actual/threatened death | 56.3 | 55.6 | 57.9 | .863 |

| Response involved fear/hopelessness/horror | 59.6 | 59.5 | 60.0 | .971 |

| Recurrent intrusive distressing recollections | 71.1 | 74.2 | 64.3 | .497 |

| Recurrent distressing dreams | 64.4 | 67.7 | 57.1 | .492 |

| Acting or feeling as if event was recurring | 33.3 | 41.9 | 14.3 | .069 |

| Intense psychological distress to cues | 53.3 | 61.3 | 35.7 | .111 |

| Physiological reactivity to cues | 54.5 | 60.0 | 42.9 | .287 |

| Efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, conversations about event | 60.0 | 58.6 | 63.6 | .772 |

| Avoiding activities/places related to event | 61.5 | 71.4 | 36.4 | .043 |

| Inability to recall important aspect of event | 25.0 | 31.0 | 9.1 | .152 |

| Diminished interest/participation in activities | 47.5 | 51.7 | 36.4 | .385 |

| Detachment or estrangement from others | 37.5 | 44.8 | 18.2 | .120 |

| Restricted range of affect | 39.5 | 46.4 | 20.0 | .142 |

| Sense of foreshortened future | 39.5 | 44.8 | 22.2 | .226 |

| Difficulty falling/staying asleep | 76.7 | 76.0 | 80.0 | .847 |

| Irritability/outbursts of anger | 60.0 | 64.0 | 40.0 | .317 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 50.0 | 52.0 | 40.0 | .624 |

| Hypervigilance | 63.3 | 68.0 | 40.0 | .236 |

| Exaggerated startle response | 53.3 | 48.0 | 80.0 | .190 |

Note. MDE = Major Depressive Episode diagnosed on SCID. OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. PTSD = Post-Traumatic Distress Disorder.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

More depressed women reported experience avoidance behaviors (i.e., avoiding activities and places) in connection with a traumatic experience (p = .043). However, endorsement of all other PTSD symptoms was comparable across groups (all p >.051; see Table 4).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate high rates of co-occurring anxiety disorders both in women who met full criteria for current MDE and those who did not. More women with current MDE met criteria for anxiety disorders than those without current MDE. However, in general, symptom endorsement was comparable across groups, clearly suggesting that pregnant women who screen positively for depression even without a formal diagnosis of MDE are experiencing psychological distress and impairment that might be reduced with intervention.

Our data indicate that pregnant women with positive screens for MDE—whether they meet full diagnostic criteria for MDE or not—need to be assessed further for anxiety and PTSD symptoms and diagnoses. Screening items to assess for likely presence of highly comorbid disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders) could be incorporated into existing screening procedures. Future research should evaluate the utility of including additional anxiety-related items in clinical assessments as a supplement to initial screening. For example, O’Hara et al. (2012) recently demonstrated the utility of three items (felt restless, felt panicky, and depressed mood) in identifying women at risk for anxiety and/or depression in the postpartum period. A similarly brief set of screening items could be evaluated for use with women at risk for antenatal depression and/or anxiety to identify those women in need of further clinical assessment.

In addition to screening, clinicians should also be trained to assess both anxiety and depression for all pregnant women. Particularly in settings where regular use of longer measures is not feasible due to time constraints, a two-tier assessment process could be of use both in efficient allocation of available clinical resources and identifying those women at risk for antenatal depression and comorbid disorders (Breedlove & Fryzelka 2011). Providing additional training with regard to anxiety disorders may also improve medical providers’ interest in consistently screening for both anxiety and depression during pregnancy (Coleman et al. 2008).

The primary limitation of our study is the lack of data regarding women who were below the positive screen threshold score on the BDI. It is quite likely that, despite the good sensitivity and specificity reported using a BDI score of 16, that many women, particularly those near the threshold, would also meet criteria for anxiety diagnoses. Since we did not interview women who screened negatively on the BDI, we do not have data regarding the sensitivity or specificity of the BDI. The study is also limited by the relatively low rate of minorities and the relatively high education level of the subjects. However, the sample did include a number of women who were served by maternal health clinics, which are publically funded sites designed to provide care during pregnancy and the postpartum to women who have no other means to pay for care. The sample also included women from very low SES groups. Though there is an emphasis on screening for perinatal depression now, we believe that the findings from our data set still reflect contemporary comorbidity and emphasize the need for more comprehensive screening.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate comparable rates of anxiety symptoms among women screening positive for depression, highlighting the need for additional evaluation of anxiety in pregnant women to increase access to treatment and improve outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This study was supported in part by NIMH research grant MH59688 awarded to Dr. Stuart.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L, Sundtröm-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Wulff M, Bondestam K, Astrom M. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: A population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:148–154. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, Donohue B, Teichner GA, Crum T, Howell J, DeCato LA. A controlled evaluation and description of individual-cognitive problem solving and family-behavior therapies in dually-diagnosed conduct-disordered and substance-dependent youth. J Child and Adoles Subst. 2001;11:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psych Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psych. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson T. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G. Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiat. 2004;49:726–735. doi: 10.1177/070674370404901103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove G, Fryzelka D. Depression screening during pregnancy. J Midwifery Wom Heal. 2011;56:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho HF, Murray L, Royal-Lawson M, Cooper PJ. Antenatal anxiety disorder as a predictor of postnatal depression: A longitudinal study. J Affect Disorders. 2011;129:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman V, Carter M, Morgan M, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ screening patterns for anxiety during pregnancy. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:114–123. doi: 10.1002/da.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ. 2001;323:257–260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman J, Tyler-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health. 2010;19:477–490. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disorders. 2004;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb WL, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, Gavard JA, Mostello DJ. Screening for depression in pregnancy: Characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva H, Stuart S, O’Hara MW, Bowman-Reif J. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Arch Women Ment Hlth. 2011;14:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0184-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva H, Stuart S. Risk factors for depressive symptoms in adolescent pregnancy in a late-teen subsample. Arch Women Ment Hlth. 2014;17:155–158. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Lam SK, Lau SMSM, Chong CSY, Chui HW, Fong DYT. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1102–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287065.59491.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression, and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: Whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disorders. 2003;74:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Watson D, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D’Angelo D. Brief scales to detect postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1237–1243. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Steward MD. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2004;26:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubertsson C, Hellström J, Cross M, Sydsjö G. Anxiety in early pregnancy: Prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Women Ment Hlth. 2014;17:221–228. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamero M, Marcos T, Gutierrez F, Rebull E. Factorial study of the BDI in pregnant women. Psychol Med. 1994;24:1031–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700029111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, Krist AH. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA- J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315:380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, O’Hara M, Gorman L. Postpartum anxiety and depression: Onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:420–424. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter-Dallay AL, Giaconne-Marcesche V, Glatigny-Dallay E, Verdoux H. Women with anxiety disorders during pregnancy are at increased risk of intense postnatal depressive symptoms: A prospective survey of the MATQUID cohort. Eur Psychiat. 2004;19:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BRH, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioral development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav R. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]