Abstract

The objective of this article is to deliver a concise up-to-date review on hip osteoarthritis. We describe the epidemiology (disease distribution), etiologies (associated risk factors), symptoms, diagnosis and classification, and treatment options for hip osteoarthritis. A quiz serves to assist readers in their understanding of the presented material.

INTRODUCTION

Please see the Sidebar: Quiz to Assess Knowledge of Hip Osteoarthritis (True/False/Depends) with Answers.

Osteoarthritis (OA), often referred to as “wear-and-tear” arthritis, age-related arthritis, or degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of joint disorder in the US, and it is estimated that more than 27 million Americans are affected.1 As a degenerative disorder, OA can involve any joint, and it primarily affects the articular cartilage and surrounding tissues.2 OA can be broadly classified into primary and secondary types. In primary OA, the disease is of idiopathic origin (no known cause) and usually affects multiple joints in a relatively elderly population. Secondary OA usually is a monoarticular condition and develops as a result of a defined disorder affecting the joint articular surface (eg, trauma).3 This review will focus on primary hip OA with a discussion of secondary hip OA.

The hip joint is one of the body’s largest weight-bearing joints, only secondary to the knee joint, and is commonly affected by OA.4 The current accepted understanding of hip OA is that although articular cartilage is mainly affected, the entire joint also is affected. The OA process involves progressive loss of articular cartilage, subchondral cysts, osteophyte formation, periarticular ligamentous laxity, muscle weakness, and possible synovial inflammation.2 There is a growing consensus that OA is not the result of a singular process affecting the joints but rather results from a number of distinct conditions, each associated with unique etiologic factors and possible treatments that share a common final pathway.5 The effects of OA on the large joints of the lower extremities, including the hips, can result in reduced mobility and marked physical impairment that can lead to loss of independence and to increased use of health care services. As such, OA may have a profound effect on activities of daily living and lead to substantial disability and dependency in walking, stair climbing, and rising from a seated position. Several risk factors are linked to the development of hip OA including age, gender, genetics, obesity, and local joint risk factors. However, the exact primary hip OA etiology remains unknown,6–8 and a universal protocol is lacking for its diagnosis and treatment. In this report, we describe hip OA epidemiology (disease distribution), etiologies (associated risk factors), symptoms, diagnosis and classification, and treatment options.

PREVALENCE

The difference between the clinical and radiographic prevalence of hip OA remains unclear; however, most epidemiologic studies of hip OA involve radiographic parameters to establish disease prevalence.9,10 Research suggests that hip OA is epidemiologically distinguishable from OA affecting other joints.11 For example, only a small percentage of patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) to address primary hip OA required a total knee arthroplasty (3%-7%) and vice versa.12 In a prominent US-based population study,13 prevalence of symptomatic hip OA was reported at 9.2% among adults age 45 years and older, with 27% showing radiologic signs of disease; prevalence was slightly higher among women. A systematic review of radiographic hip OA prevalence demonstrated an increase in mean prevalence with advancing age for both men and women.10 Men have a higher prevalence of hip OA before age 50, whereas women have a higher prevalence thereafter.14 Caucasian populations also have a higher hip OA prevalence that ranges between 3% and 6% as compared with 1% or less in Asians, blacks, East Indians, or native Americans,15,16 suggesting a genetic predisposition. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, lifetime risk for symptomatic hip OA is 18.5% for men and 28.6% for women.5

ETIOLOGIES AND RISK FACTORS

OA is a chronic disorder affecting synovial joints. Although sometimes referred to as “degenerative joint disease,” this term is a misnomer. The degenerative process manifested by progressive loss of articular cartilage is accompanied by a reparative process with reactive bone formation, osteophyte growth, and remodelling.5 The dynamic process of destruction and repair determines the final disease picture. OA is not primarily an inflammatory process, and synovial inflammation, when found, usually is not accompanied by a systemic rise in inflammatory markers. Primary OA (also termed idiopathic), generally is a diagnosis of exclusion and is believed to account for the majority of all hip OA.10 Aging is assumed to contribute to the development of hip OA mainly because of the inability to specifically define an underlying anatomic abnormality or specific disease process leading to the degenerative process.

Genetic factors also may play a role in hip OA, possibly by the inheritance of an anatomical abnormality such as acetabular dysplasia. A sibling study demonstrated a higher risk for hip OA among those who had an affected sibling, as demonstrated by structural changes noted on hip radiographs.17 Secondary (from a known cause) OA results from conditions that change the cartilage environment. These conditions include trauma, congenital or developmental joint abnormalities, metabolic defects, infection, endocrine disease, neuropathic conditions, and disorders that affect the normal structure and function of hyaline cartilage. Secondary hip OA occurs when a condition results in an anatomic abnormality, which can be relatively subtle, that predisposes the hip to mechanical factors that lead to degenerative changes.5

Risk factors associated with hip OA can be divided into local risk factors that act on the joint level and more general risk factors.

Local Risk Factors

Joint Dysplasia

Conditions such as acetabular dysplasia and other developmental disorders leading to structural joint abnormalities are believed to play a major role in development of hip OA later in life.5 Mild dysplastic changes often can go unnoticed and predispose to hip OA.

Quiz to Assess Knowledge of Hip Osteoarthritis (True/False/Depends) with Answers.

|

1. Aging and other risk factors contribute to hip osteoarthritis (OA). Answer: True. However, not all hip OA is related to the aging process. Young people can develop secondary hip OA from trauma, congenital dysplasia and developmental disorders, infection, metabolic conditions, and other causes. |

|

2. Patients should wait as long as possible before undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA). Answer: False. Patients who fail nonsurgical treatment should not delay undergoing THA because delay correlates with worse clinical outcomes even after surgery is performed. |

|

3. Hip OA primarily is a disease of cartilage. Answer: True. Progressive loss of articular cartilage often is accompanied by a reparative process that involves sclerosis and osteophyte formation. |

|

4. Joint stiffness in hip OA may not improve for several hours, or it may last throughout an entire day. Answer: False. Morning stiffness helps to differentiate OA from rheumatoid arthritis. In rheumatoid arthritis, joint stiffness may not improve for several hours or it may last throughout the entire day. In OA, stiffness typically lasts for only a few minutes and subsides in 30 minutes or less. Movement and physical activity that loosens the joint generally improve OA. |

|

5. Certain radiographic parameter measurements as described by Kellgren and Lawrence1

can help clinicians assess hip OA severity. Answer: False. Currently, there is no gold standard with which to measure and report the prevalence of radiographic primary hip OA. The Kellgren and Lawrence method of diagnosis is the most common method with which to measure radiographic OA severity. A limitation associated with this system is its reliance on the presence of osteophytes, which correlate poorly with hip pain. |

|

6. Studies demonstrate that viscosupplementation injections slow OA symptom progression. Answer: False. Most clinical studies show that these treatments are no more effective than a placebo and are not recommended as hip OA treatment. |

|

7. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective first-line hip OA treatments. Answer: True. Both topical NSAIDs (such as capsaicin) and oral NSAIDs may be considered as an adjunct for symptomatic pain relief in addition to core treatments for patients with OA. Diclofenac and etoricoxib are the most efficacious NSAIDs for pain relief in hip OA, producing a moderate to large effect size. However, NSAIDs should be used with caution to avoid potential complications associated with long-term use. |

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957 Dec;16(4):494–502. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.16.4.494.

Trauma

Fractures involving the joint articular surface can lead to secondary posttraumatic arthritis. It is unclear whether isolated labral tears contribute to hip OA.18,19

General Risk Factors

Age

The Research on Osteoarthritis/Osteoporosis Against Disability study,20 which prospectively followed 745 Japanese men and 1470 Japanese women for 3 years, revealed that age greater than 60 years is an important risk factor for radiographic OA. However, it is also clear that aging of joint tissues and OA development are distinct processes. Chondrocalcinosis, an age-related matrix change observed in radiographs of arthritic joints, may contribute to OA by stimulating production of proinflammatory mediators.20

Sex

Hip OA prevalence is higher among men younger than age 50 years, whereas women have the highest prevalence after age 50 years.21 This finding may be attributable to postmenopausal changes21,22 and is supported by observations from multiple studies that report protective effects of estrogen replacement therapy and hip OA.21

Obesity

Excess body weight is a risk factor for OA not only in weight-bearing joints, but also in the hand.23,24 Excess weight produces increased load on the joint, but there is growing evidence for a metabolic contribution to OA as well.25

Genetics

Several studies suggest that genetics have an important role in the etiopathogenesis of hip OA, and a twin study reported on a 60% risk for hip OA attributable to genetic factors.26 Another study demonstrated that having a first-, second-, or third-degree relative who undergoes THA for hip OA increases a person’s risk for having the procedure.27

Occupation

Certain occupations involving heavy manual work and high-impact sports activities are linked to OA in the hip and other joints later in life.28,29 Repetitive stress and biomechanical overload, especially in the setting of a preexisting hip joint anatomical abnormality, are likely causes.30 Farmers are particularly prone to hip OA.31 However, no credible evidence demonstrates that exercise and physical activity are directly related to hip OA in the general population.

SYMPTOMS

The most common symptom of hip OA is pain around the hip joint (generally located in the groin area). The pain can develop slowly and worsen over time (most common) or pain can have a sudden onset. Pain and stiffness can develop in the morning or after sitting or resting. Stiffness typically lasts for only a few minutes and subsides over 30 or fewer minutes. Movement and activity that loosen the joint generally improve OA symptoms. Later in the progression of the disease, painful symptoms may occur more frequently, including during rest or at night (see Sidebar: Common Hip Osteoarthritis Symptoms).

DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION

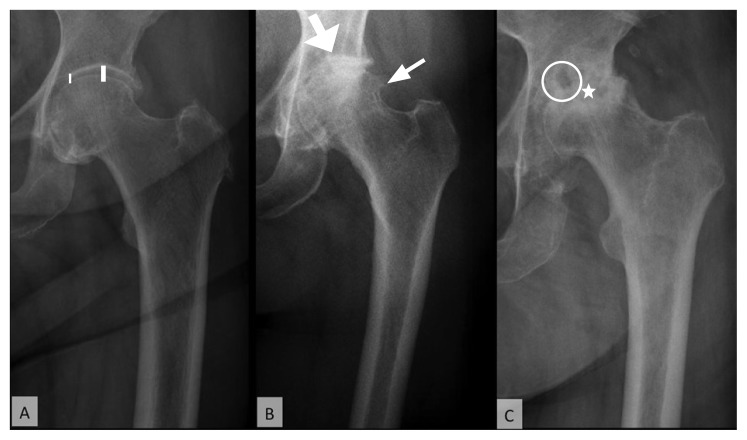

Hip OA often can be diagnosed upon clinical presentation alone, although imaging investigations can be useful to both confirm a diagnosis and to monitor disease progression (Figure 1A–C).5 After taking a careful medical history that includes a review of associated hip OA risk factors, a clinician should perform a focused clinical examination of the affected hip. The examination should include an inspection and comparison of leg length between the affected and opposite sides, an evaluation of a possible joint fixed position denoting deformity, and a gait assessment. These steps should be followed by palpation of regional bony prominences and tendons to assess for tenderness and/or injuries. A neurovascular assessment of both lower extremities and range of motion of the affected joint should be performed with a comparison to the contralateral side. Additional tests may provide more information regarding underlying conditions that lead to hip OA.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior hip radiograph. A. Narrowing of the superomedial joint space is seen in the region marked by white lines. B. Bone-on-bone osteoarthritis (thicker arrow) with osteophyte formation (thinner arrow). C. End-stage osteoarthritis with femoral head deformation (star) and cyst formation (circle).

Common Hip Osteoarthritis Symptoms.

Pain and stiffness that is worse in the morning or after sitting or resting

Pain in the groin or thigh that radiates into the buttocks or knee

Pain that flares with vigorous activity

Stiffness in the hip joint that makes it difficult to walk or bend

“Locking” or “sticking” of the joint and a grinding noise (crepitus) during movement caused by loose cartilage fragments and other tissues interfering with smooth hip motion

Decreased range of motion in the hip that affects the ability to walk and may cause a limp

In 1957, Kellgren and Lawrence32 described a grading scale for the radiologic assessment of OA that remains the most widely used classification system; however, this scale is not specific for hip OA grading. In 1963, Kellgren33,34 described four grades of hip OA based on the degree of joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, arthritic changes affecting the bone margins, and gross deformity as the following: Grade 1, doubtful OA with possible joint space narrowing medially and subtle osteophyte formation around the femoral head. Grade 2, mild OA with definite joint space narrowing inferiorly with definite osteophyte formation and slight subchondral sclerosis. Grade 3, moderate OA with marked narrowing of the joint space, small osteophytes, some sclerosis and cyst formation, and deformity of the femoral head and acetabulum. Grade 4, obliterated joint space with features seen in grades 1 to 3, large osteophytes, and gross deformity of the femoral head and acetabulum. Several other radiographic classification systems exist such as Croft’s grade,35 minimal joint space,35 and the Tönnis classification.36

Other imaging studies such as computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging typically are not required for diagnosis and usually are reserved for the identification of secondary causes or presurgical planning. Blood tests may be ordered to help confirm a diagnosis and to rule out other inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, especially if joint symptoms are associated with morning stiffness and synovial inflammatory changes. Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, and cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody tests are among the most common laboratory studies ordered; when testing for hip OA, however, these test results are expected to fall within defined limits. The American College of Rheumatology has established clinical criteria and radiologic parameters that are commonly used for hip OA diagnosis in clinical practice.

An important contrast between patient symptoms and radiographic findings may be observed. Patients with marked radiographic changes may not necessarily demonstrate severe correlating clinical symptoms and vice versa. Some patients with high-grade radiographic hip OA may be asymptomatic.37

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Nonpharmacologic Treatments

Exercise

An exercise program that does not involve high-impact activities usually is advocated and is associated with pain reduction.38 Aquatic exercises also improve function.38,39 Exercises that strengthen and stretch the muscles around the hip can support the hip joint and ease hip strain. Certain activities and exercises that can aggravate the hip joint should be recognized and avoided (see Sidebar: Common Activities that Exacerbate Osteoarthritis Hip Pain). Activities that necessitate twisting at the hip such as golf or are high impact such as jogging should be replaced with activities that exert less stress on the hip joint such as gentle yoga, cycling, or swimming. Manipulation and stretching should be considered as adjuncts to core treatments, particularly for hip OA.37

Common Activities that Exacerbate Osteoarthritis Hip Pain.

Prolonged inactivity

Abduction and external and internal rotation

Bending

Getting into and out of a car

Prolonged physical activity

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is the mainstay of treatment in mild and early hip OA and is aimed at strengthening hip muscles and maintaining joint mobility. Physical therapy that is provided during the later stages of hip OA may provide little or no benefit.40

Weight Reduction

Gaining 10 pounds can exert an extra 60 pounds of pressure upon a hip with each step.41 Unloading the joint through weight loss can slow cartilage loss and decrease joint impact. Weight recommendations that address hip OA are based upon findings from many cohort studies.42–45 An individualized exercise program combined with effective behavioral strategies aimed at weight loss may be most beneficial in reducing pain for overweight patients.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation should be considered as an adjunct to core treatments for pain relief for patients with hip OA.46

Temperature Extremes

Hot and cold treatments sometimes are effective pain relief modalities. Heat treatments enhance circulation and soothe stiff joints and tired muscles. Cold treatments slow circulation, reduce swelling, and alleviate acute pain. A patient may need to experiment and/or alternate use of heat and cold therapies to determine which is most effective.

Proper Footwear and Bracing/Joint Supports/Insoles

Patients should be educated about appropriate footwear that features shock-absorbing properties to address lower limb OA.46 Patients with OA who have biomechanical joint pain or instability may be considered for assessment of bracing/joint supports/insoles as an adjunct treatment.46 Bracing may have a role in modifying biomechanics to treat hip OA, although more research in this area is necessary.5

Assistive Devices

Walking sticks, tap turners, canes, and other devices should be considered as adjuncts to core treatments for people with OA who have specific problems with activities of daily living. If needed, patients can be referred for further evaluation and treatment from occupational and physical therapists and/or specialized disability device and equipment companies.46

Acupuncture is not recommended as OA treatment. Patient education can help to incorporate multiple approaches into hip OA treatment and minimize risk factors.

Pharmacologic Treatments

Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Acetaminophen typically is recommended as a first-line medication for OA.47 However, the role of acetaminophen for short-term relief of hip OA pain remains equivocal.47 Topical Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (such as capsaicin) may be considered as an adjunct therapy for pain in addition to core treatments. Acetaminophen and topical NSAIDs should be considered ahead of oral NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors, or opioids.46 Topical capsaicin should be considered as an adjunct to core treatments for knee or hand OA but has limited use in hip OA because of hip joint depth.46 If acetaminophen is insufficient for pain relief, NSAIDs may be more efficacious.45 Diclofenac and etoricoxib are the most efficacious NSAIDs for pain relief in hip OA, producing moderate to large effects.46 However, NSAIDs should be used with caution to avoid potential complications such as gastrointestinal tract bleeding and adverse cardiovascular events associated with long-term use.46,47 If acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs provide insufficient pain relief, opioid analgesics may be considered. Opioid medications, however, are not routinely used because of concerns regarding their side effects and long-term addiction potential.48 Risks and benefits should be considered, particularly for older patients.46

Rubefacients

Topical rubefacients should not be used to treat OA.46

Glucosamine/Chondroitin

Use of glucosamine or chondroitin products for OA treatment is not recommended.46

Intra-Articular Injections

Corticosteroids; hyaluronic acids; and, relatively recently, platelet-rich plasma injections, are the most common modalities to treat pain associated with hip OA. Corticosteroids offer short-term pain relief,47 and guidelines recommend their use as an adjuvant to other nonsurgical treatment modalities.45 Although the literature in this area is scarce and data are weak, recent evidence suggests that caution should be exercised when using multiple intra-articular steroid hip injections before THA because multiple injections have been associated with a significantly higher risk for prosthetic joint infection than a single injection administered before THA.44,49,50 Clinical trials do not provide strong support for the clinical use and value of hyaluronic acid injections.46,47 The use of platelet-rich plasma remains under investigation in clinical trials, and data available from small studies do not provide substantial evidence for a clear clinical role.5

Surgical Treatments

Hip Arthroscopy

Studies on the use of arthroscopy in hip OA are not high quality. Arthroscopy, which primarily is performed during early OA stages, provides temporary relief and is associated with a high conversion rate to THA (9.5%–50%).51

Total Hip Arthroplasty

THA is today’s surgical modality for patients with intractable pain, for those who have failed nonsurgical treatment, and for those with severe functional impairment. Approximately 1 million THA procedures are performed globally each year for patients with advanced hip OA.52 This procedure repeatedly demonstrates cost-effectiveness in clinical trials.53 Hip implant longevity has been demonstrated, with as many as 95% of prostheses remaining functional at 10 years, which is consistent in certain populations where the patient has good overall general physical health, ability to exercise, remains active and maintains a good weight for which more than 80% of prostheses can remain functional at 25 years.53–55 Primary care providers should advise symptomatic patients who fail nonsurgical treatment to avoid waiting unnecessarily to undergo THA because evidence demonstrates that prolonged delays correlate with worse clinical outcomes after THA.53 Progressive pain, disability, and functional impairment can cause further unnecessary damage to tissues and joints that affect the biomechanical environment in other joints. Interference with usual activities of daily living can be unnecessarily affected; this can be especially problematic for younger patients who work and are more socially and physically active.

Hip Resurfacing

Although originally developed as a substitute for THA for younger patients who failed nonsurgical treatment, current evidence indicates that hip resurfacing is suitable for a very specific subset of patients, usually young active men with large femoral heads, as an alternative to THA.55–57

European League against Rheumatism 2005 Recommendations for the Management of Hip Osteoarthritis.

The European League against Rheumatism published comprehensive recommendations in 2005 for the management of hip osteoarthritis (OA).1 The group adopted a multidisciplinary approach (involving rheumatologists, orthopedic surgeons, and an epidemiologist) and represented 14 European countries proposing evidence-based treatment interventions for the treatment of hip OA. Powered by an extensive literature review, experts proposed key hip OA recommendations:

|

Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:669–81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.028886.

CONCLUSION

OA is a chronic disorder affecting synovial joints and a leading cause of disability in the US and worldwide. Current thought is that hip OA results from a number of distinct conditions, each associated with unique etiologic factors and possible treatments that share a common final pathway. The most common symptom of hip OA is pain around the hip joint (generally located in the groin area). Most of the time, the pain develops slowly and worsens over time, or pain can have a sudden onset. Aging and genetic factors are important contributing causes of hip OA. The European League against Rheumatism 2005 Recommendations for the Management of Hip Osteoarthritis advocate a multidisciplinary approach for the management of hip OA (see Sidebar: European League against Rheumatism 2005 Recommendations for the Management of Hip Osteoarthritis)Nonpharmacologic (low impact exercises, weight reduction, and adjunct therapies), pharmacologic (mainly acetaminophen and topical NSAID medication) and surgical options (hip arthroscopy in early OA, total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing in advanced OA) may be used in the treatment of hip OA. It is important for clinicians to avoid unnecessary delay in referring patients with advanced hip OA for surgical consideration appropriately to prevent worse clinical outcomes after THA.

Acknowledgment

Brenda Moss Feinberg, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital signs: Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Mar 10;66(9):246–53. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutton CW. Osteoarthritis: The cause not result of joint failure? Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Nov;48(11):958–61. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.11.958. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.48.11.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson J. Osteoarthritis of the young adult hip: Etiology and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010 Aug;26(3):355–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. Erratum in: Clin Geriatr Med 2013 May;29(2):ix. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy NJ, Eyles JP, Hunter DJ. Hip osteoarthritis: Etiopathogenesis and implications for management. Adv Ther. 2016 Nov;33(11):1921–46. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0409-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0409-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: An integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Feb;466(2):264–72. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986 Dec;(213):20–33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-198612000-00004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965 Nov;38(455):810–24. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankel S, Eachus J, Pearson N, et al. Population requirement for primary hip-replacement surgery: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 1999 Apr 17;353(9161):1304–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06451-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagenais S, Garbedian S, Wai EK. Systematic review of the prevalence of radiographic primary hip osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Mar;467(3):623–37. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0625-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushnaghan J, Dieppe P. Study of 500 patients with limb joint osteoarthritis. I. Analysis by age, sex, and distribution of symptomatic joint sites. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Jan;50(1):8–13. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.1.8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.50.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao Y, Zhang C, Charron KD, Macdonald SJ, McCalden RW, Bourne RB. The fate of the remaining knee(s) or hip(s) in osteoarthritic patients undergoing a primary TKA or THA. J Arthroplasty. 2013 Dec;28(10):1842–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.10.008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan J, Helmick C, Renner J, Luta G. Prevalence of hip symptoms and radiographic symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in African-Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2009 Apr;36(4):809–15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felson DT. Preventing knee and hip osteoarthritis. Bull Rheum Dis. 1998 Nov;47(7):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence JS, Sebo M. The geography of osteoarthritis. In: Nuki G, editor. The aetiopathogenesis of osteoarthrosis. London, UK: Pitman; 1980. Apr, pp. 155–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhaya B, Barooah B. Osteoarthritis of hip in Indians an anatomical and clinical study. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 1967;1(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanyon P, Muir K, Doherty S, Doherty M. Assessment of a genetic contribution to osteoarthritis of the hip: Sibling study. BMJ. 2000 Nov 11;321(7270):1179–83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7270.1179. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7270.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann G, Mendicuti AD, Zou KH, et al. Prevalence of labral tears and cartilage loss in patients with mechanical symptoms of the hip: Evaluation using MR arthrography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 Aug;15(8):909–17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy JC, Busconi B. The role of hip arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of hip disease. Can J Surg. 1995 Feb;38(Suppl 1):S13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muraki S, Akune T, Oka H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for radiographic knee osteoarthritis and knee pain in Japanese men and women: A longitudinal population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 May;64(5):1447–56. doi: 10.1002/art.33508. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.33508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felson DT. Epidemiology of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:1–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrianakos AA, Kontelis LK, Karamitsos DG, et al. ESORDIG Study Group. Prevalence of symptomatic knee, hand, and hip osteoarthritis in Greece. The ESORDIG study. J Rheumatol. 2006 Dec;33(12):2507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Cirillo PA, Reed JI, Walker AM. Body weight, body mass index, and incident symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Epidemiology. 1999 Mar;10(2):161–6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199903000-00013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014 Feb;28(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellam J, Berenbaum F. Is osteoarthritis a metabolic disease? Joint Bone Spine. 2013 Dec;80(6):568–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.09.007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacGregor AJ, Antoniades L, Matson M, Andrew T, Spector TD. The genetic contribution to radiographic hip osteoarthritis in women: Results of a classic twin study. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Nov;43(11):2410–6. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2410::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-E. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2410::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelt CE, Erickson JA, Peters CL, Anderson MB, Cannon-Albright L. A heritable predisposition to osteoarthritis of the hip. J Arthroplasty. 2015 Sep;30(9 Suppl):125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.062. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris P, Hart D, Jawad S. Risks of osteoarthritis associated with running: A radiological survey of ex-athletes. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Sarna S. Osteoarthritis of weight bearing joints of lower limbs in former élite male athletes. BMJ. 1994 Jan 22;308(6923):231–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6923.231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6923.231. Erratum in: BMJ 1994 Mar 26;308(6932):819. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6932.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulsky SI, Carlton L, Bochmann F, et al. Epidemiological evidence for work load as a risk factor for osteoarthritis of the hip: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031521. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris EC, Coggon D. Hip osteoarthritis and work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015 Jun;29(3):462–82. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957 Dec;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellgren J. The Epidemiology of Chronic Rheumatism. Vol. 2. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1963. Atlas of standard radiographs in arthritis. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atlas of standard radiographs of arthritis. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D. Defining osteoarthritis of the hip for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Sep;132(3):514–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115687. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tönnis D. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1987. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araújo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011 Nov;19(11):1270–85. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.08.009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 22;(4):CD007912. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartels E, Juhl C, Christensen R, Hagen K, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, Lund H. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. 2016 Mar 23;3:CD005523. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden N, et al. EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 May;64(5):669–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.028886. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.028886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes C, Leyland KM, Peat G, Cooper C, Arden NK, Prieto-Alhambra D. Association between overweight and obesity and risk of clinically diagnosed knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Aug;68(8):1869–75. doi: 10.1002/art.39707. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtis GL, Chughtai M, Khlopas A, et al. Impact of physical activity in cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health: Can motion be medicine? J Clin Med Res. 2017 May;9(5):375–81. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3001w. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr3001w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felson DT, Niu J, Clancy M, Sack B, Aliabadi P, Zhang Y. Effect of recreational physical activities on the development of knee osteoarthritis in older adults of different weights: The Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Feb 15;57(1):6–12. doi: 10.1002/art.22464. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennell K. Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis. J Physiother. 2013 Sep;59(3):145–57. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70179-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(13)70179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.da Costa BR, Reichenbach S, Keller N, et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017 Jul 8;390(10090):e21–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31744-0. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012 Apr;64(4):465–74. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osteoarthritis: Care and management. London, UK: NICE; 2014. Feb, (Clinical guideline [CG177] [Internet]). [cited 2017 Aug 11] Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177. [Google Scholar]

- 48.da Costa BR, Nüesch E, Kasteler R, et al. Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 17;(9):CD003115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCabe PS, Maricar N, Parkes MJ, Felson DT, O’Neill TW. The efficacy of intra-articular steroids in hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016 Sep;24(9):1509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chambers AW, Lacy KW, Liow MHL, Manalo JPM, Freiberg AA, Kwon YM. Multiple hip intra-articular steroid injections increase risk of periprosthetic joint infection compared with single injections. J Arthroplasty. 2017 Jun;32(6):1980–3. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.030. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piuzzi NS, Slullitel PA, Bertona A, et al. Hip arthroscopy in osteoarthritis: A systematic review of the literature. Hip Int. 2016 Jan-Feb;26(1):8–14. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000299. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5301/hipint.5000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pivec R, Johnson AJ, Mears SC, Mont MA. Hip arthroplasty. Lancet. 2012 Nov 17;380(9855):1768–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60607-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daigle ME, Weinstein AM, Katz JN, Losina E. The cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review of published literature. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012 Oct;26(5):649–58. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Apr;89(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marshall DA, Pykerman K, Werle J, et al. Hip resurfacing versus total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review comparing standardized outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Jul;472(7):2217–30. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3556-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3556-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sehatzadeh S, Kaulback K, Levin L. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: An analysis of safety and revision rates. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12(19):1–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matharu GS, Pandit HG, Murray DW, Treacy RB. The future role of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Int Orthop. 2015 Oct;39(10):2031–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2692-z. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-015-2692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]