Abstract

The two largest providers of HIV care in the US are the Veterans Administration and Kaiser Permanente. Both organizations are significantly outperforming the general population in implementing the HIV Care Continuum, which involves 1) testing and diagnosis, 2) linkage to care, 3) retention in care, 4) initiation and continuation of antiretroviral therapy, and 5) achievement of viral suppression. Adherence to the care continuum allows people living with HIV to achieve viral suppression to levels where the virus is undetectable. Such individuals are less likely to transmit the virus than are other infected individuals not receiving medical care. In this interview article, leaders from the two comprehensive integrated health care systems share insight about how their organizations achieve top-quality HIV care outcomes, as well as their ongoing efforts to identify and close gaps in care.

INTRODUCTION

People living with HIV who receive comprehensive HIV treatment and take antiretroviral medications as prescribed can achieve viral suppression, meaning that the virus is undetectable in their bodies. This result is sustainable over time. Such individuals are at less risk of the development of AIDS or of transmitting the virus than are other infected individuals who are not receiving medical care.

Subject Matter Experts.

Lisa Backus, MD, PhD, Deputy Chief Consultant, Measurement and Reporting, Patient Care Services/Population Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA

Pam Belperio, PharmD, BCPS, National Public Health Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Patient Care Services/Population Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, Los Angeles, CA

Michael A Horberg, MD, MAS, FACP, FIDSA, Executive Director, Research, Community Benefit, and Medicaid Strategy, Mid-Atlantic Permanente Medical Group, Rockville, MD; Director of HIV/AIDS Program, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA; and Clinical Lead, HIV/AIDS, Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute, Oakland, CA

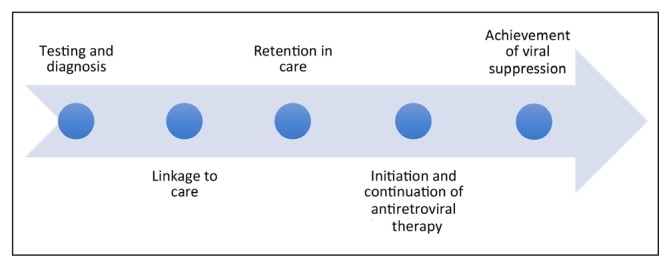

The two largest providers of HIV care in the US are the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Kaiser Permanente (KP). Compared with the general US population, HIV patients in these integrated delivery systems had significantly better outcomes along the five steps of the HIV care cascade (also called HIV treatment cascade and HIV care continuum). This care cascade involves 1) testing and diagnosis, 2) linkage to care, 3) retention in care, 4) initiation and continuation of antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, and 5) achievement of viral suppression (Figure 1).1 Independently published results from both organizations demonstrate that improved outcomes along the HIV care cascade are being achieved in these integrated health care systems.2–4

Figure 1.

HIV care cascade.a

a The HIV care cascade (or continuum) “is a model that outlines the sequential steps or stages of HIV medical care that people living with HIV go through from initial diagnosis to achieving the goal of viral suppression (a very low level of HIV in the body).”1 Each step in the cascade has been associated with lower mortality, improved patient health, and even lower transmission of HIV.2

1. Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015 Aug 1;69(4):474–80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615.

2. What is the HIV care continuum? [Internet]. Washington, DC: HIV.gov; last updated 2015 Aug 4 [cited 2017 Sep 29]. Available from: www.aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/care-continuum/.

Here, edited and condensed for space, is a recent conversation with experts from the VA and KP (see Sidebar: Subject Matter Experts) about how their organizations achieve top-quality HIV care outcomes and how these results might be replicated elsewhere.

CHALLENGES

Institute for Health Policy (IHP): In the general population, more than 50% of individuals diagnosed with HIV are not engaged in care. Why is this number so high?

Pam Belperio

One key reason is that many people living with HIV in the general population may not have insurance coverage, particularly comprehensive prescription plans, like what is available through the VA and KP. They may not regularly seek out a health care practitioner because they pay out of pocket, especially for younger populations. For the same reason, they may not be engaged in health care in general.

Michael Horberg

I also think you have to break this down by demographic groups. When we start talking about Latino or African American populations, I think there are still disparities and a lack of trust toward the health care system, reflecting a lack of access to care. And I think certainly if you start talking about the rural South, you’re talking about lack of easy access to quality care.

And when you also talk about the men-having-sex-with-men population, there has always been a certain amount of homophobia, whether internal or external—that has precluded good access to health care.

Lisa Backus

We know that men in general don’t have quite as much health care-seeking behavior, so getting them diagnosed and engaged in care is more difficult. Inadequate insurance coverage for that population is often a big barrier to care. And of course, there’s the big stigma issue. Being engaged in care may readily identify you as having HIV, so the stigma associated with accessing care might be a reason as well.

IHP: What has been the most challenging segment of the HIV care cascade for your organization to make improvements on and why?

Backus

For the VA, the biggest challenges at this point are still getting people diagnosed, and then retention in care. In general, we do an incredibly good job once people are retained in care—getting them “on” ARV therapy and getting them virally suppressed. The challenge that remains for us is in the diagnosis and then in getting them to stay in care once they are initially linked to care.

Horberg

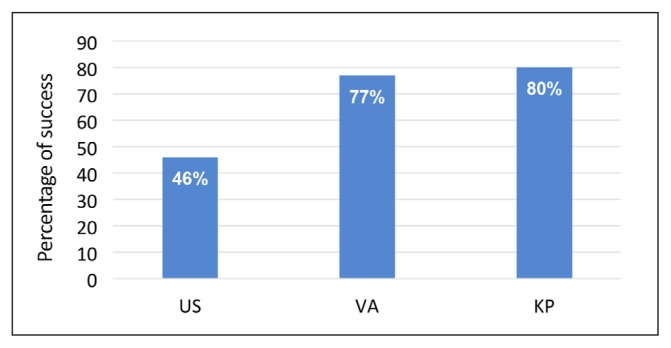

For KP, initial linkage to care has been really high; we average 97%. We can get patients in for their first set of labs [laboratory studies], but then of course the challenge is retaining them. The VA (77%) and KP (80%) have exceptionally high numbers for retention in HIV care—really, this is exceptional [Figure 2]. It’s important to note that we’ve got many patients who don’t meet the classic definition of care retention—which is 2 face-to-face visits per year with their HIV specialist or primary care physician—but they have been taking their medications, getting their refills and even getting their labs. Many are virally suppressed, especially those who have been in care longer.

Figure 2.

Retention in care.

KP = Kaiser Permanente; VA = US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Of course, we are always concerned about follow-up and about patients whose viral loads go up, or who develop other illnesses. So, when we say they don’t meet the classic definition of retention, that doesn’t mean there is no contact. We are using video visits and secure messaging to maintain close contact. We recently presented data from the KP Mid-Atlantic Region showing that patients with one face-to-face visit annually, plus e-mail contact or e-mail plus video visit, had viral suppression comparable to those with at least two face-to-face visits annually.

But again, it’s all about the demographic groups. For example, a particularly challenging population for us has been heterosexual black women. Retaining them in care has been difficult for a lot of the reasons, including stigma, childcare obligations, and distrust of the health system.

Among the younger population of men who have sex with men, there are some with a sense of immortality. And frankly, there’s a sense among some individuals that health care providers are doing so well in treating HIV that if they delay being treated, they will still be okay. KP and the VA are two integrated health systems that are very good at providing the care, but you have to want to be cared for. That’s not to put the blame on the patient; sometimes health care providers aren’t good at communicating why retention in care is important.

Belperio

Yes, I think that’s right on target. If you look at data published by the VA, it is that younger population that really is the most challenging.

ACHIEVING POSITIVE OUTCOMES

IHP: Both the VA and KP perform substantially better in engaging patients in care than the US general population [Figure 2]. Can you describe what your organization does to get such good results?

Belperio

We’ve been able to maximize the use of our electronic medical record and patient registry. Once patients are identified as being HIV positive, we can monitor those patients electronically, both from a national standpoint as well as from a local VA facility standpoint. These are incredibly helpful tools that allow us to know who our population is, where they are located, and if they are indeed engaged in care.

The other thing that’s a factor in both KP and the VA is that our patients are insured and have drug benefits. Within the VA, barriers to obtaining HIV medications are minimized. For example, the VA has on formulary all FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved HIV antiretrovirals. [The VA] has very low or no copays depending on income, refills can be ordered over the phone or the Internet, medications can be mailed, and the VA will provide 90-day supplies for people on stable regimens. Whereas in the general population, drug benefits are certainly not as accessible as they are within the VA and KP.

Horberg

We’ve also put information systems in place that empower the staff in our multidisciplinary care teams—which can include the HIV specialist, care/case manager, HIV clinical pharmacist, dedicated medical assistants, social worker, etc. Each Region and Medical Center in the biggest Regions can define the team composition differently to best meet their needs. We don’t just leave care management to physicians. We have data systems in place that help us identify patients who are falling through the cracks early on, and then do appropriate outreach. Often the nonphysician clinical staff is most aware of who needs an appointment, who has not had labs done, etc.

Patients can call the team about any element of their care. The care team can see if their labs are up to date, when they were last seen, or if their AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP)a status is current. Some KP Regions have medical financial assistance programs to help people who are insured, but their medication copays may be a hindrance to good adherence.

Additionally, we’ve really tried to respect the patients so that they feel welcomed and want to come to the clinic and want to engage with our staff. You know, it doesn’t matter if it’s HIV or any other condition. If you don’t like your doctor and you don’t like the clinic staff, then you’re less likely to want to be engaged in care.

Do we have care gaps? Absolutely. We’re not going to say, “Our retention in care is at 70% to 80%, and the US population is generally at 43%, so we’re good.” No, that means we have a 20% to 30% gap, and the patients in the gap are at greater risk. We try to engage them as I described earlier.

Backus

The VA also uses multidisciplinary care teams. A lot of our HIV clinics have case managers, social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrists in them because many patients with HIV have multiple diagnoses. Some have mental health disorders. Some have substance use disorders. Some have other medical comorbidities.

Additionally, a lot of the HIV physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants provide complete primary care, so they can also address a patient’s hypertension or coronary disease—conditions that we’re now seeing in the aging HIV population. If you only have to go to one doctor and can get all your many needs addressed, that will help retain people in care.

The information systems are important. The VA does some national reporting, and we can tell facilities about how many people they have engaged in care, how many people they have on ARVs, or the population that is virally suppressed.

We know that health care professionals are basically all incredibly hard working and want to do the right thing. If you point out to them that the most important metrics are engagement in care, being on ARVs, and being virally suppressed, clinicians will then come up with the local intervention to improve those numbers. Local ownership of innovation is important because often the available clinic staff, the available clinic hours, the available clinic structure is very different across facilities. It makes a huge difference whether you’re in San Francisco, [CA] or you’re in Fargo, North Dakota. We’ve learned that if you just give local clinicians some sense of how they’re doing on the HIV care cascade, they can come up with much more creative interventions to address issues than we ever could do from a national perspective. Sometimes you just have to give the care team some feedback; then they’ll figure out how to address the problem.

Horberg

We’re also firm believers in “think globally, act locally.” We’ve set parameters around performance levels we expect to achieve, but we know darn well that what works in Baltimore [MD], for example, isn’t necessarily going to work in [Washington] DC. Or what works in San Francisco [CA] won’t necessarily be what works in Fresno [CA].

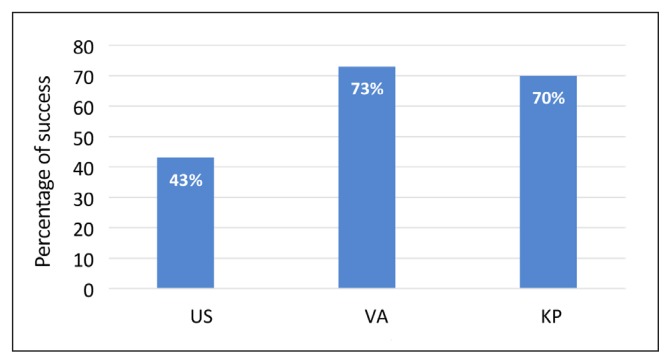

IHP: Once engaged in care, patients from the VA and KP are much more likely to initiate and continue using ARV therapy than the US general population [Figure 3]. What are you doing right?

Figure 3.

Initiation and continuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART).a

a Some patients received ART without meeting the classic definition of engaged in care.

KP = Kaiser Permanente; VA = US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Horberg

Our clinical guideline is that if you’re HIV positive, you should be on medications. We’re putting things in place to help patients get to their appointments and to help them afford their medications if that’s an issue. We’re checking their test results regularly. We believe patients should get their viral load checked at least twice a year and more frequently if it’s not controlled.

The HIV care cascade is a very classic method, which says you have to be retained in care … to be on medicines, leading to being virally suppressed. In KP—and I’m assuming the same is true for the VA—if you look at all of the patients, and not just those “retained” by the cascade definition, 85% to 86% are virally suppressed. So, it’s a much higher number if you get rid of that restriction of having to be also seen twice a year.

Backus

The VA and KP work in very similar ways [in this regard]. We also have policy from our Central Office that says everybody should be on ARVs, and we report on the number of people on ARVs. We don’t do it in the traditional care cascade, where you have to have met a prior criterion. At the end of the day, we report on everybody even if they don’t meet the strict criteria of two visits a year for engagement in care. Are you on ARVs? Are you virally suppressed? That’s what we care about.

The other point is that the VA population has the benefit of continuous insurance. If you’re in the VA, we’re going to be taking care of you. In other systems, patients have to reapply for the ADAP or sometimes end up losing their Medicaid coverage—these people might not get on ARVs.

As mentioned before, we also try to make it as easy as possible for people to get their medications and to have a supply on hand.

Belperio

Our clinical pharmacists are very actively engaged with the HIV programs within the VA. More than 80% of the facilities have a clinical pharmacist who is involved with their HIV clinic. These pharmacists work very hard in terms of maintaining adherence and making sure people’s medication refills are being addressed appropriately. They ensure that medication changes, drug interactions, and any adverse events that patients may be experiencing are managed appropriately. Questions and issues regarding medications can be addressed and handled by the pharmacists as well. Oftentimes these pharmacists are much more readily available than the patient’s practitioner may be.

The VA also has an HIV community advisory board that’s made up of veterans, and that group is nationally representative across the country. There are approximately 15 veterans on the rotating board, with advisory board meetings generally twice a year. Veterans bring up issues that they have heard from their communities that they would like to see addressed or resolved and provide feedback on what their experience has been with VA HIV care. We really take to heart those discussions and try to address those issues.

As an example, one of the things that prompted a 90-day HIV drug fill with refills within the VA was that patients who were on stable HIV treatment were running into issues with having to come in or contact their physician for refills, leading to gaps in their treatment. This is a really important piece that the community advisory board alerted us to.

Horberg

To improve adherence, we try to do whatever we can to provide 90-day refills in our system. We actually see higher rates of adherence among our patients who use mail-order pharmacy.

Well-functioning mail-order pharmacies are a great way to improve adherence, and I think that’s also related to why we have such good viral suppression and such high adherence rates. And we try to bring “in-house” whatever we can, including full pharmacy benefits and support, our specialists, and care teams. ADAP has been really helpful because we can therefore have that medication adherence data readily available to us. You’re not just guessing, “Are they picking up their medicines based on the viral loads?” You’re actually seeing the patient’s medication refill data.

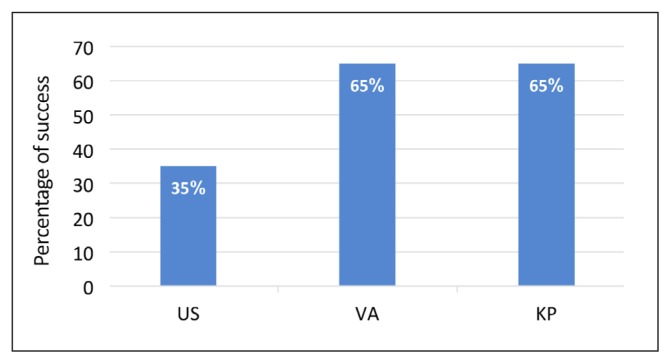

IHP: Both the VA and KP perform substantially better in achieving viral suppression than the US general population [Figure 4]. Can you describe what your organization does to get such good results?

Figure 4.

Achievement of viral suppression.a

a Some patients achieved viral suppression without meeting the classic definition of engaged in care.

KP = Kaiser Permanente; VA = US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Backus

It’s pretty much all the things that we mentioned before. It is 90-day prescription refills. It’s having a mail-order pharmacy service. It’s that we report on rates of viral suppression. It’s that local clinicians have tools that make it easier to see who is virally suppressed and who is not.

Belperio

It’s about multidisciplinary teams and addressing mental health issues. [See next question.]

Backus

Again, clinical pharmacists play a big role. At the end of the day, viral suppression is all about did you receive your medications? Did you take your medications? Have you continued to take your medications? The pharmacists are great at following-up on this stuff.

Horberg

Part of the problem is that everyone thinks there’s one step. There isn’t. Our data showed that the clinical pharmacist was more critical than a physician, especially when it came to adherence. But it’s not just the clinical pharmacist. It’s also the integration of care. It’s everyone, including the full multidisciplinary care team and the patient, being empowered and feeling responsible and creating our own safety net. Of course, I’m always cautious about using that term safety net. If the patient is really struggling or if the patient goes in and out of incarcerations, we say one of the first things you [should] do is just get yourself to our office, and we’ll take it from there. Just don’t divorce yourself from the system and don’t think you don’t have a medical home.

IHP: Can you elaborate on the importance of mental health integration?

Belperio

Within many of the VA HIV clinics, there is mental health integration, either directly in the HIV clinic itself or through a direct connection with a particular mental health provider or clinic. Such a relationship makes for a very easy transition between addressing the patient’s HIV medical needs and his/her mental health or substance use needs as well.

There’s a lot of education that is done within our mental health and substance use disorder programs regarding HIV care and special needs of HIV patients as it relates to their mental health and substance use disorders. Educational outreach on the management of alcohol and substance use disorders in HIV has really been an important piece. The collaboration between HIV clinicians and the mental health and substance use disorder clinic has really made an incredible difference in making sure those needs get addressed so that they don’t interfere with the medical care that’s being provided to the HIV patients.

Horberg

I would add that by making mental health internal to the health program, you’re also making sure that, by it being seamless, there’s no drug interactions and the medical and psychiatric treatments are complementary to each other, if not even synergistic.

Belperio

It goes back to that whole idea of one-stop shopping and keeping a patient-centered focus. Bringing the care to the patient, rather than the patient having to go to another clinic location on another day to see his/her mental health practitioner. The goal is really to center care around the patient, rather than sending the patient off into different directions for mental health services.

OBSTACLES PATIENT POPULATIONS FACE

IHP: What segments of your patient populations are most vulnerable to falling off the HIV care cascade and at which segments? What are the most important obstacles these populations face?

Backus

For the VA, I think two groups of patients are most vulnerable. First, there is a group of patients with multiple diagnoses, sometimes quadruple diagnoses. The population contends with homelessness, mental health disorders, substance use disorders, in addition to their HIV. For a lot of those people, figuring out where you’re going to get your next meal or where you’re sleeping far outweighs concerns about how they’re going to get their HIV medications.

The other vulnerable population is the relatively newly diagnosed young individuals who are asymptomatic. Michael [Horberg] alluded to this population. They’re 25 [years old], and they feel great. Their peers may tell them, “Don’t worry about it. There are great drugs, and you can wait 10 years or 15 or 20 years to take the drugs.”

Both of those are populations we lose on the engagement to care aspect of the care cascade. We get them linked the first time, but then they do not make it to subsequent appointments.

Horberg

We have concerns about African American women and people of color in general from the national [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] data. The issue is that strategies to address various demographic groups are not necessarily the same. It’s not a one-size-fits-all proposition. And we know the face of the epidemic and the nature of the epidemic vary geographically. So, what I might do in San Francisco [CA]may not work in other cities. And sometimes that applies even within our own self-imposed geographic Regions like Northern California or the Mid-Atlantic.

FUTURE INNOVATIONS

IHP: What innovations does your organization have on the horizon that will help to further improve HIV care in the near future?

Backus

The VA has recently expanded its use of telehealth and secure messaging to make it easier for people to connect with their clinicians. We are particularly targeting this strategy on the younger population that we think we may be missing. They want to send text messages, or they want to just communicate with their practitioner via e-mail.

Some of the homeless population have only cell phones because they don’t have fixed addresses. We used to send only appointment letters to people. Well, if you’re homeless, I can’t send the appointment letter because you have no address. So, we have to change how we notify people about appointments and say, “Okay, we’re going to send text alerts to remind people that they have appointments.”

We realize that some of these innovations are generational. Some of the older people want a letter, and they don’t have e-mail and don’t want you calling them. So, we have to figure out the right form of patient outreach and adapt it to an individual.

We’re also doing some technologic things to make data more available to care teams because we do think it makes it easier for clinicians to assess their panels and assess their performance.

To date, the VA has not been prescribing that much PrEP [preexposure prophylaxis] to prevent HIV infection. I think that’s one of the other things coming in the future, and we do some better targeting of PrEP.

Belperio

Consent to testing has been a barrier to HIV testing in the past. Some of those walls have been broken down, and we are not requiring the written consent that had been required and has been a big barrier in the past. Now, HIV testing can be done with oral informed consent from the patient. That consent is documented in the electronic record by the clinician.

I will also emphasize the role of clinical video telehealth and empowering the patient to become more engaged in their care by making things easier for them to stay linked in care. If the HIV provider is not at the VA clinic location that’s closest to the patient, then our video telehealth services can help them access an HIV practitioner remotely.

My HealtheVet, VA’s patient portal, is a way for patients to communicate with their clinician and track their care through various electronic modalities. It empowers them to take on extra responsibility regarding their health care and makes it easy for them to contact their practitioners. The turnaround is quick, and patients seem to really like using that method of communicating with their clinician and following their own progress. They have access to all of their lab data, visits, [and] prescriptions, and they can use it to refill prescriptions electronically.

So, that’s been a really positive advancement. My HealtheVet is not specific to HIV, but it’s been used widely across the HIV segment within the VA.

Horberg

We are trying to get more patients on PrEP and identifying more and more patients at risk, especially among men having sex with men, women at high risk, and women [wanting] to get pregnant. A big focus going forward is a renewed emphasis on STDs [sexually transmitted diseases]—diagnosis and treatment, both among men having sex with men and HIV-positive patients. This focus includes STD self-testing of throat and rectum for the men-having-sex-with-men population. We know that urine tests didn’t pick up all cases of gonorrhea and chlamydia.4

Like the VA, KP has a patient portal, and we’re trying to encourage patients to ask their doctors or other members of the care team questions online before there’s an issue or an issue boils up to a crisis. Refills of medication, requesting labs to be ordered, and communicating lab results in a more timely manner are all part of the patient portal.

We also are applying video visits in telehealth, especially for PrEP but also for some of the HIV return visits. Data from the KP Mid-Atlantic Region showed that one in-person visit with the HIV specialist plus e-mail did not have statistically significantly different results compared with two in-person visits a year for viral suppression. So, we do know that for a lot of patients they don’t need to be physically seen to be doing well.

I also think renewed emphasis on multidisciplinary care teams, especially with attention to mental health screening, alcohol and drug use, and then getting the patients into appropriate programs have been important. I’m not sure any of those in and of themselves are an “innovation,” but it’s like everything we’ve been talking about here. Every incremental bit contributes to the overall good results.

On a cautionary note, I think there has been a certain sense that things have been pretty good. So, I think there needs to be renewed emphasis on both prevention and treatment; there always needs to be. Today, there’s uncertainty about federal HIV care financing. Drastic cuts have been proposed. We could see a lot of the great gains that have been made thrown into great disarray as a byproduct of that.

Acknowledgment

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

AIDS Drug Assistance Programs are a set of programs in all 50 states in the US that provide Food and Drug Administration-approved HIV treatment drugs to low-income patients in the US. The programs are administered by each state with funds distributed by the US government.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Aug 1;69(4):474–80. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Klein DB, et al. The HIV care cascade measured over time and by age, sex, and race in a large national integrated care system. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015 Nov;29(11):582–90. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0139. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2015.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2014. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data, United States and 6 dependent areas, 2012; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison P. Urine tests miss sexually transmitted infections [Internet] New York, NY: Medscape; 2015. Oct 16, [cited 2017 Sep 29]. Available from: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/852800. [Google Scholar]