Abstract

α-Branched amines are ubiquitous in drugs and natural products, and consequently, synthetic methods that provide convergent and efficient entry to these structures are of considerable value. Transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines have the potential to be highly practical and atom-economic approaches for the synthesis of a diverse and complex array of α-branched amine products. These strategies typically employ readily available starting inputs, display high functional group compatibility, and often avoid the production of stoichiometric waste byproducts. A number of C–H functionalization methods have also been developed that incorporate cascade cyclization pathways to give amine-substituted carbocycles, and in many cases, proceed with the formation of multiple stereogenic centers. Advances in the area of asymmetric C–H bond additions to imines have also been achieved through the use of chiral imine N-substituents as well as by enantioselective catalysis.

Keywords: C–H activation, Amines, Nitrogen heterocycles, Asymmetric synthesis, Homogeneous catalysis

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

α-Branched amines are a privileged class of compounds found in drugs and natural products, and synthetic strategies to prepare these compounds in a convergent and efficient manner are critically important. Nucleophilic additions of organometallic reagents to imines are some of the most extensively used methods for the convergent synthesis of α-branched amines (Scheme 1a).[1] However, these approaches first require the preparation or purchase of the organometallic reagents. Furthermore, these strategies produce stoichiometric waste byproducts and are often not compatible with the types of functionality commonly found in drugs and natural products such as protic groups like alcohols and primary and secondary amides and electrophilic groups exemplified by carbonyl derivatives. In this regard, ionic and strongly basic organolithium reagents display the least functional group compatibility, while softer and more covalent organoboron reagents, which often require the use of a transition-metal catalyst for additions to imines, are some of the most compatible.

Scheme 1.

Strategies for Nucleophilic Addition to Imines

In recent years, transition-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization has emerged as a very powerful and highly efficient strategy for the catalytic generation of organometallic nucleophiles from simple starting inputs (Scheme 1b).[2] This approach theoretically has the potential to overcome all of the limitations associated with prefunctionalized organometallic reagents due to the potentially enormous number of diverse C–H bond activation substrates, the high functional group compatibility of many transition-metal catalysts as highlighted by Rh(III) based systems, [3] and the atom-economic nature of C–H functionalization, which often eliminates the production of stoichiometric waste byproducts.

In Section 2 of this review, methods for direct C–H bond additions to imines to provide α-branched amine products and nitrogen heterocycles will be presented. Following this, Section 3 details imine-directed C–H bond insertion across C=C π bonds followed by cyclization upon the imine directing group. This type of approach can provide efficient entry to amine-substituted carbocyclic products and often allows for the generation of several contiguous stereogenic centers. Section 4 will then cover recent progress toward asymmetric C–H bond additions to imines by highlighting the advances that have been achieved through the use of both chiral imine N-substituents as well as enantioselective catalysis. The direct addition of terminal alkynyl C–H bonds to imines, while an important contribution, has recently been reviewed and will not be discussed in the context of this review.[4]

2. Direct C–H Bond Addition to Imines to Provide Racemic Products

2.1. C(sp2)–H Bond Addition

2.1.1. Rh Catalysis

In 2011, Bergman, Ellman and co-workers reported the seminal examples of rhodium-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines (Scheme 2).[5] To achieve the desired reactivity, it was necessary to employ a cationic Rh(III) catalyst with a noncoordinating counterion. Analogous Ru(II) and Ir(III) catalyst systems under the optimal reaction conditions proved ineffective, and the highest yields were achieved when the less expensive 2-arylpyridine inputs 1 were used in excess. For the C–H bond partner, both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing functionalities were well tolerated at different positions on the aromatic ring. The reaction displayed good functional group compatibility and tolerated reactive functionalities including aldehydes, ketones, and acidic acetanilide moieties. Furthermore, both aryl and alkyl aldimines 2 reacted cleanly and in good yields. While C–H bond additions to sulfonyl-protected imines were demonstrated, the majority of couplings were carried out for N-Boc-protected aldimines due to the popularity of the Boc protecting group, which can be removed in straightforward fashion and in high yield.

Scheme 2.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Arylation of Imines via C–H Functionalization

Following this report, our laboratory then conducted a detailed mechanistic study (Scheme 3), including kinetic analysis and X-ray crystallographic structure determination of key intermediates along the catalytic cycle (Figure 1).[6] For our kinetic analysis, an N-isopropoxycarbonyl imine was selected as a model substrate because the N-isopropoxycarbonyl group does not cleave upon treatment with acid, but provides comparable yield to the corresponding N-Boc protected imine under identical conditions. This modification eliminates any potential for competitive deprotection of the imine protecting group under the slightly acidic reaction conditions. The proposed mechanism of Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H bond addition to imines is outlined in Scheme 3. Treatment of the [Cp*RhCl2]2 precatalyst with the AgSbF6 halide abstracting agent provides cationic Cp*Rh(III). In the presence of 2-phenylpyridine, the active cationic Cp*Rh(III) promotes a nitrogen-directed C–H bond activation through a redox-neutral concerted metalation deprotonation (CMD) pathway with a second equivalent of 2-phenylpyridine acting as base to afford an 18-electron catalyst resting state 4, which is stabilized by a third molecule of 2-phenylpyridine bound through the nitrogen and pyridinium salt 5.[7] Stoichiometric preparation of catalyst resting state 4 allowed for the clean isolation and characterization of this cyclometalated complex by X-ray crystallography. Loss of 2-phenylpyridine from 4 affords the 16 valence-electron complex 6 containing an open coordination site that allows for the reversible binding of the imine electrophile to give 7. Following this, a 1,2-migratory insertion of the Rh–C bond into the imine π bond leads to the seven-membered metallacycle 8 that is stabilized through a dative bond from the N-isopropoxycarbonyl oxygen. This complex has also been prepared stoichiometrically and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Coordination of another molecule of 2-phenylpyridine then furnishes 9. Turnover of the catalytic cycle occurs when the amide ligand facilitates the next round of CMD to regenerate 6 while releasing the branched amine product 10.

Scheme 3.

Proposed Mechanistic Cycle for Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to Imines.

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structures for key intermediates along the catalytic cycle of Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines. Hydrogen atoms and SbF6− counter anions have been omitted for clarity.

The results of our kinetic experiments revealed the reaction to be first order with respect to catalyst resting state 4. In contrast, the reaction is inverse first order for the reacting 2-phenylpyridine C–H bond partner, consistent with the requirement that 2-phenylpyridine be released from resting state 4 in order to engage the catalytic cycle.

In a related report, the Shi laboratory published the rhodium-catalyzed arylation of sulfonyl-protected imines 12 by C–H functionalization (Scheme 4).[8] Here, a preformed cationic Rh(III) catalyst was employed and reactions were conducted in t-BuOH or toluene. While a range of sulfonyl-protected imines were evaluated, N-tosyl aldimines provided the highest yields and were used for the majority of the substrate scope. The authors also note that an N-tert-butanesulfinyl imine was evaluated in the transformation, but lacked sufficient electrophilicity to undergo reaction. For the C–H bond partner, both 2-pyridine and 2-quinoline were shown to be efficient directing groups. Substrates containing electron-withdrawing and electron-donating functionalities, including an acidic phenol, were well tolerated and provided the desired N-sulfonyl branched amines in good yield.

Scheme 4.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to Sulfonyl-Protected Imines

In 2012, Shi and co-workers also conducted a mechanistic analysis of Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines where relevant cyclometalated intermediates along the catalytic cycle were isolated and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 2).[9] In this study, 2-phenylpyridine and an N-tosyl aldimine were selected as the substrates of interest, and detailed kinetic analysis revealed that for this transformation migratory insertion of the Rh–C across the π bond of the imine electrophile is the rate-determining step. Figure 2 depicts relevant cyclometalated intermediates that were characterized by X-ray diffraction.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structures of cyclometalated intermediates for Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H bond additions to N-sulfonyl imines. Hydrogen atoms and SbF6− counter anions have been omitted for clarity.

Following our evaluation of 2-arylpyridine C–H bond partners we later expanded the scope of this reaction to include synthetically useful amide directing groups (Scheme 5).[10] In analogy to our earlier findings, it was necessary to employ a cationic Rh(III) catalyst system, and the use of a completely noncoordinating B(C6F5)4 anion provided the highest yields. A range of N, N-dialkyl benzamides 16 were effective directing groups, but use of a pyrrolidine amide provided the highest yield. A range of functionalities and substitution patterns were well tolerated on both the C–H bond partner and aromatic aldimine, and the synthetic utility of the α-branched amine addition products was demonstrated by the facile synthesis of isoindoline and isoindolinone heterocycles.

Scheme 5.

Amide-Directed Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to N-Sulfonyl Imines

In 2012, the Shi laboratory reported the first examples of alkenyl C–H bond addition to N-sulfonyl aldimines (Scheme 6).[11] For the olefinic C–H bond partner 19 both five- and six-membered alkenyl substrates coupled in high yield, while a seven-membered substrate reacted in low yield. In general couplings to electron-deficient N-tosyl aldimines gave higher yields due to the enhanced electrophilicity imparted by electron withdrawing groups. The evaluation of an N-Boc-protected aldimine required the use of modified reaction conditions due to the sensitivity of the Boc group to the pivalic acid additive, and under these modified conditions a low yield of the desired product was obtained. For this substrate, the reaction was conducted in the absence of the acid additive and with CH2Cl2 as reaction solvent.

Scheme 6.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Alkenyl C–H Bond Addition to Imines

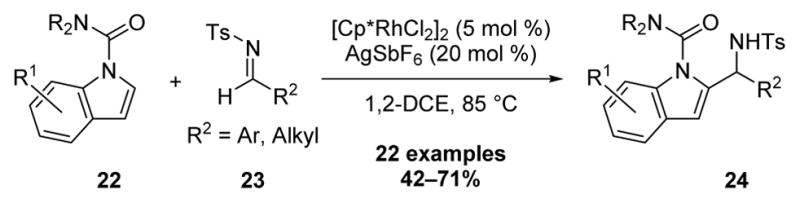

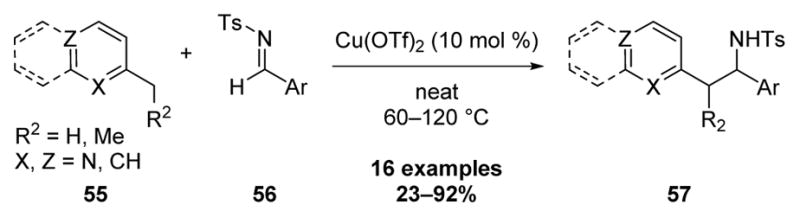

The Li laboratory has reported on Rh(III)-catalyzed heteroaromatic C–H bond addition to imines (Scheme 7).[12] For the substrate scope of this reaction the authors employed a removable N, N-dimethylcarbamoyl directing group for regioselective functionalization of indoles 22 at the 2-position with both alkyl and aromatic N-tosyl aldimines 23.

Scheme 7.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Indole C–H Bond Addition to Imines

In 2014, the Bolm laboratory published a strategy for Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H additions to cyclic imines 26 (Scheme 8).[13] Interestingly, in their evaluation of different metal catalysts the authors found that a cationic Ru(II) catalyst system also provided the desired addition product but in only moderate yield. Several heteroaromatic directing groups were effective for this transformation, including pyridine, pyrimidine and quinoline functionalities, and the functionalization of both aromatic and heteroaromatic C–H bonds was demonstrated.

Scheme 8.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Imines

In recent years, our laboratory has reported a general strategy for heterocycle synthesis by cascade C–H bond additions to polarized π bonds followed by cyclization with the directing group for C–H functionalization.2a In 2013 we extended this annulation approach to imine additions for the synthesis of highly substituted pyrroles 30 (Scheme 9).[14] Reaction of highly substituted α,β-unsaturated oximes with the N-tosyl imine of ethyl glyoxylate 29 provided the pyrroles in good yield.

Scheme 9.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Pyrrole Synthesis

The vast majority of C–H functionalization reactions involve the two-component coupling of a C–H bond and a reactive electrophile. However, from the standpoint of convergent introduction of functionality, three-component couplings have the potential to provide efficient entry into diverse and complex products. In 2016, our laboratory published a preliminary example of three-component C–H functionalization using a highly-activated N-tosyl imine derived from ethyl glyoxylate (Scheme 10).[15] While the reaction proceeded in good yield and allowed for the desired sequential coupling of the two electrophiles, a low 2:1 diastereoselectivity was observed.

Scheme 10.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Three-Component C–H Bond Addition Cascade with an N-Tosyl Imino Ester

2.1.2. Co Catalysis

In 2012, the first examples of cobalt-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines by Yoshikai and co-workers were reported (Scheme 11).[16] Expanding upon their earlier reports of Co-catalyzed C–H additions to alkynes and alkenes the authors employed a CoBr2/N-heterocyclic carbene catalyst in conjunction with a stoichiometric Grignard reagent to generate a low-valent cobalt species under reductive conditions.[17] In contrast to earlier reports of C–H bond additions to imines (vide supra), the use of sulfonyl- and carbamoyl-protected imines were not tolerated. The scope of this reaction was evaluated for C–H additions of 2-arylpyridines to N-p-methoxyphenyl aromatic aldimines. In addition to the 2-pyridyl directing group, addition of 1-phenylpyrazole to N-phenyl aldimine was also carried out. In the absence of N-heterocycle directing groups, a self-coupling of N-p-methoxyphenyl aldimines was observed, and following an acidic reaction workup under air this procedure gave isoindolinones.

Scheme 11.

Low-Valent Cobalt-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to N-Aryl Imines

The following year Kanai, Matsunaga, and co-workers detailed the first examples of Co(III)-catalyzed C–H functionalization using a high-valent preformed catalyst 39 (Scheme 12).[18] In their analysis of different cationic Co(III) sandwich complexes the authors tested a series of substituted Cp ligands, but found the archetypal Cp* to be the most effective for C–H bond addition to imines. Commercial Co(II) and Co(III) salts were also evaluated as catalysts, but showed no activity. Using 2-phenylpyridine as the C–H bond partner, the scope of this reaction was explored with a range of aromatic aldimines bearing a readily removable 2-thiophenylsulfonyl protecting-group.

Scheme 12.

Co(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition to Sulfonyl-Protected Imines

Later that year the same group extended this methodology to the functionalization of heteroaromatic indole C–H bonds (Scheme 13).[19] The addition of potassium acetate provided a noticeable increase in yield, and when an electron-deficient imine was employed a high yield was maintained with only 0.5 mol % of catalyst 39. For both coupling partners 40 and 41 the reaction was compatible with a range of electron-withdrawing and electron-donating functionalities, and additions to both aryl and alkyl aldimines proceeded in good yield.

Scheme 13.

Co(III)-Catalyzed Indole C–H Bond Addition to N-Sulfonyl Imines

2.2. Alkyl Azaarene C(sp3)–H Bond Addition

2.2.1. Pd Catalysis

In 2010, Huang and co-workers published the seminal example of transition-metal-catalyzed sp3 C–H bond addition to imines (Scheme 14).[20] Using a Pd(OAc)2 catalyst and 1,10-phenanthroline (Phen) as ligand the reaction proceeds without the use of strong base. Azaarene benzylic C–H bond additions to electron-deficient N-tosyl aldimines proceeded in good yield, while additions to tosyl imines bearing electron-donating substituents proceeded in only moderate yields. To address this issue, the authors found that application of the more electrophilic p-nitrobenzenesulfonyl (Ns) N-protecting group resulted in more efficient reactivity for electron-rich substrates. Several azaarenes 43 were employed in this study, including 2-substituted pyridines and quinolines, and 2-methylquinoxaline.

Scheme 14.

Pd(II)-Catalyzed 2-Alkyl Azaarene C(sp3)–H Bond Addition to Sulfonyl-Protected Imines

2.2.2. Sc Catalysis

Later that year the same group reported a related strategy for Sc(III)-catalyzed C(sp3)–H functionalization of 2-alkyl azaarenes 46 with N-sulfonyl aldimines 47 (Scheme 15).[21] For the coupling of 2,6-lutidine and the N-tosyl imine of benzaldehyde a broad range of Lewis acids were evaluated including halogen and triflate complexes of B, Al, Fe, Zn, Ni, Cu, Ag metals. Direct C–H addition to both aromatic and alkenyl sulfonyl protected-imines provided the desired branched amines (Scheme 15a). Further synthetic application was demonstrated for aromatic imines 50 appended with electrophiles such as esters and Michael acceptors (Scheme 15b). For these substrates, benzylic C–H addition to the imine followed by intramolecular cyclization provided efficient entry to isoindoline heterocycles 51. In the case of imine tethered Michael acceptors, the products were obtained as single diastereomers.

Scheme 15.

Sc(III)-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Bond Addition of 2-Alkyl Azaarenes to N-Sulfonyl Imines

2.2.3. Cu Catalysis

In 2011, Rueping and co-workers developed an earth-abundant approach for benzylic C–H functionalization of 2-alkyl azaarenes 52 employing a Cu(II) catalyst (Scheme 16).[22] Among the Lewis acid catalysts explored in this transformation, Yb(OTf)3, Co(OAc)2, and Bi(OTf)3 were all effective, but Cu(OTf)2 in combination with 1,10-phenanthroline as ligand provided the highest yield. The C–H functionalization of pyridine, pyrazine, pyridizine, quinoline, and quinoxaline heterocycles proceeded in moderate to good yields. This approach was also applied to γ C–H functionalization of 4-alkyl azaarenes.

Scheme 16.

Cu(II)-Catalyzed 2-Alkyl Azaarene C(sp3)–H Bond Addition to Boc- and Sulfonyl-Protected Imines

In 2012, the laboratories of Kanai and Matsunaga also reported on the Cu(II)-catalyzed azaarene sp3 C–H bond addition to imines (Scheme 17).[23] A series of Lewis acidic metal triflates derived from Mg, Al, In, Fe, Zn, Bi, Sc, and Cu all promoted this transformation, although the latter showed the highest catalytic activity. Reactions were conducted under neat conditions and additions to both electron-rich and electron-poor N-tosyl aromatic imines proceeded smoothly. Enolizable alkyl imines failed to react, and while several alkyl azaarenes were effective substrates, only trace product was observed for 2-methylbenzoxazole.

Scheme 17.

Cu(II)-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Bond Addition of 2-Alkyl Azaarenes to N-Tosyl Imines

2.2.4. Fe Catalysis

In 2011, Huang and co-workers detailed an earth-abundant iron-catalyzed strategy for alkenylation of 2-alkyl azaarenes 58 via C–H bond addition to imines followed by elimination of the amine functionality (Scheme 18).[24] For electron-rich and electron-deficient aldimines both tosyl- and nosyl-protected imines provided high yields of the desired 2-alkenylated azaarenes 60. The authors also evaluated a Boc-protected imine, but for this substrate the reaction proceeded in low yield. The majority of azaarene substrate scope was carried out using substituted 2-methylquinolines. To achieve good yields with 2-ethylquinoline, 2-methylquinoxaline and 2-methylpyridines, addition of strongly basic KOt-Bu (20 mol %) to the reaction mixture was required. No product was observed when a control reaction was performed with only KOt-Bu in the absence of the Fe-catalyst. Notably, under the standard reaction conditions a significant kinetic isotope effect (KIE) was observed suggesting a rate-limiting C–H bond cleavage and a subsequent E2-elimination process.

Scheme 18.

Fe(II)-Catalyzed 2-Alkenyl Azaarenes Synthesis via C(sp3)–H Bond Addition to Imines

3. C–H Bond Addition to π Bonds followed by Intramolecular Cyclization Upon an Imine Directing Group

Imines contain a Lewis basic nitrogen atom that can coordinate to transition-metals. This inherent ligand–metal interaction can activate the imine for attack by an organometallic nucleophile. Importantly, this interaction has also been exploited for the use of imine directing groups for C–H functionalization. In the reactions discussed in Section 3, imine directing groups were employed for C–H bond insertion across C=C π bonds to furnish seven-membered metallacycles 63 (Scheme 19). Intramolecular addition of these cyclometalated intermediates to the electrophilic carbon of the imine directing group allows for the efficient generation of a five-membered amine-substituted carbocycles 64, often with defined stereochemistry. Depending on the reaction conditions and substrates, this initial pathway is often followed by in situ tautomerization or elimination to give a more stable final product. This type of transformation has been achieved with a broad range of transition-metal catalysts and several classes of C=C π bonds, including alkynes, electron-deficient alkenes, allenes, and dienes.

Scheme 19.

Imine-Directed C–H Insertion Across C=C π Bonds Followed by Intramolecular Cyclization Upon the Imine Directing Group

3.1. Re Catalysis

In 2005, the laboratories of Kuninobu and Takai published the seminal example of C–H bond addition to an unsaturated bond followed by intramolecular cyclization upon an imine directing group (Scheme 20).[25] Several Re(I) catalysts were shown to initiate this process, however, only [ReBr(CO)3(thf)]2 showed high regioselectivity for insertion across unsymmetrical alkynes (R3 ≠ R4). For the aromatic aldimine C–H bond partner 65 both electron-neutral and electron-donating groups were well tolerated on the aromatic ring, while incorporation of an electron-deficient CF3 substituent resulted in low yield of the desired aminoindene. A variety of internal aromatic alkynes 66 were evaluated, and for unsymmetrical derivatives, aminoindenes were formed with excellent regioselectivity.

Scheme 20.

Re(I)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition/Annulation Cascade for Aryl Aldimines and Internal Alkynes

Following their initial report on the rhenium-catalyzed synthesis of aminoindenes from aryl aldimines and alkynes, Kuninobu and Takai developed a different strategy to access indenes 70 via the coupling of aromatic ketones 68 and acrylates 69 (Scheme 21).[26] Initial studies employed a preformed N-phenyl ketimine and provided aniline as a reaction byproduct. To increase the efficiency of the method, the authors developed conditions for catalytic in situ ketimine formation using aniline or p-anisidine as an additive. Under these conditions water was the sole byproduct of the reaction. The majority of substrate scope was explored with substituted acetophenones, and although a range of functionalities and substitution patterns were well tolerated, an ortho-substituted derivative gave a poor yield of the desired indene. Couplings to alkyl acrylates were highly efficient, while addition to phenyl acrylate proceeded in low yield.

Scheme 21.

Re(I)-Catalyzed Synthesis of Indenes by In Situ Formed Imine Directed C–H Functionalization, Cyclization, and Elimination

In a subsequent paper the authors developed a related synthesis of indenes 73 from aromatic ketimines 71 and electron-deficient alkenes 72 (Scheme 22).[27] As an extension to their earlier study with acrylates, ethyl vinyl ketone was coupled to provide the indene product in moderate yield. Under the standard reaction conditions the authors found that use of an N-benzyl aldimine C–H bond partner proceeded in low yield; however, switching to a Re2(CO)10 catalyst afforded a high yield of the aminoindane intermediate. Treatment of this intermediate with either [ReBr(CO)3(thf)]2 or FeCl3 provided a high yield of the corresponding indene. This result demonstrates that under the standard reaction conditions the rhenium catalyst serves multiple roles, both facilitating the C–H activation cyclization cascade and acting as a Lewis acid to promote the elimination of an amine.

Scheme 22.

Re(I)-Catalyzed Indene Synthesis from Aryl Imines and Electron-Deficient Alkenes

In 2010, Kuninobu, Takai, and co-workers reported on the diastereoselective synthesis of aminoindanes 76 by a Re-catalyzed C–H bond addition/cyclization cascade with allenes (Scheme 23).[28] The reaction proceeded cleanly under neat conditions, and allowed for convergent assembly of two contiguous stereocenters and a quaternary carbon center. For the C–H bond partner 74, the functionalization of both ketimine and aldimine inputs were achieved in good yield. Alkenyl C–H functionalization was also accomplished, but in analogy to their earlier reports with acrylates this substrate provided a cyclopentadiene following cyclization and elimination of the amine. Good functional group tolerance was shown for couplings to alkyl allenes, while a phenyl-substituted allene provided the desired aminoindane in low yield.

Scheme 23.

Aminoindane Synthesis by Re(I)-Catalyzed Coupling of Aryl Imines and Terminal Allenes

Following the earlier reports of Rh(I)- and Ru(II)-catalyzed syntheses of aminoindenes from N–H ketimines and alkynes (vide infra), in 2016 Wang and co-workers developed a related strategy employing Re(I) catalysis (Scheme 24).[29] The addition of Na2CO3 as an inexpensive reaction additive was key toward achieving the desired reactivity. The authors proposed that this species is involved in a base-assisted deprotonation pathway for C–H activation. For both coupling partners good functional group compatibility was demonstrated, and in several cases high regioselectivity was achieved when unsymmetrical alkynes were employed.

Scheme 24.

Aminoindene Synthesis by Re(I)-Catalyzed Coupling of Aryl Ketimines and Internal Alkynes

3.2. Rh Catalysis

In 2009, the laboratories of Satoh and Miura detailed a strategy for the synthesis of indenone imines 82 by a Rh(III)-catalyzed oxidative coupling of aromatic aldimines 80 with internal alkynes 81 (Scheme 25).[30] Aromatic aldimines derived from electron-rich and poor anilines were efficient substrates for this transformation; however, an N-tert-butyl aldimine did not couple and was recovered in near quantitative yield. With respect to internal alkynes 81, a series of diarylacetylenes as well as 4-octyne were shown to be effective substrates, but application of phenylacetylene under the standard conditions provided none of the desired indenone imine and instead underwent dimerization to afford diphenylbutadiyne.

Scheme 25.

Indenone Imine Synthesis by Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization

As part of a mechanistic study into alkyne insertion induced regioselective C–H activation with Ir(III) and Rh(III) complexes, Jin and co-workers demonstrated that dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (84) was an effective substrate for Rh(III)-catalyzed indenone imine synthesis (Scheme 26).[31] In this example, the authors employed a stoichiometric amount of Rh to afford the polyaromatic product 85 in 93% yield.

Scheme 26.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition/Cyclization Cascade with DMAD

In 2010, Zhao and co-workers published the seminal example of Rh-catalyzed synthesis of unprotected aminoindenes 88 from N–H ketimines 86 and internal alkynes 87 (Scheme 27).[32] The majority of the substrate scope was carried out with diaryl ketimines to avoid potential imine/enamine tautomerization, and a range of functionalities and substitution patterns were tolerated. In general, ortho substitution was detrimental and provided either no product or required increased catalyst loading. Unsymmetrical diaryl ketones coupled with modest regioselectivity for both electron-donating and electron-poor aromatic rings, and typically favored functionalization of a substituted ring over an unsubstituted phenyl ring. Reaction of aryl- and alkyl-substituted internal alkynes provided aminoindenes in good yield, and unsymmetrical internal alkynes coupled with high regioselectivity (>30:1 rr). The authors note, however, that neither terminal alkynes nor silyl-substituted alkynes were effective substrates.

Scheme 27.

Unprotected Aminoindene Synthesis by a Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Addition/Annulation Cascade with N–H Ketimines and Internal Alkynes

The same year, the Cramer laboratory developed a syn-selective synthesis of aminoindanes 92 through a Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H addition/annulation reaction of N–H ketimines 89 and terminal allenes 90 (Scheme 28a).[33] The choice of counteranion on the Rh(I) catalyst proved essential to achieving the desired reactivity, as use of cationic or halide-containing Rh(I) complexes resulted in either allene oligomerization or imine decomposition. Biaryl phosphines were also critical, and tuning of electronic properties revealed that the electron-rich phosphine 91 provided the highest yield. In addition to symmetrical diaryl N–H ketimines, several unsymmetrical derivatives were also evaluated. For electronically different diaryl ketimines, C–H functionalization was generally preferred on the more electron-deficient aromatic ring. Notably, good yields were maintained for ketimines bearing 3- and 4-pyridyl rings. A variety of terminal allenes were used, including derivatives bearing tethered ester groups that facilitated intramolecular cyclization of the primary amine to furnish five- and six-membered lactams 95 (Scheme 28b). Finally, preliminary evaluation of an enantioselective reaction using a chiral biaryl phosphine provided a 60% yield of lactam 99 in an 84:16 enantiomeric ratio (Scheme 28c).

Scheme 28.

syn-Selective Rh(I)-Catalyzed C–H Coupling of N–H Ketimines and Terminal Allenes

In 2013, Dong and co-workers published on the Rh(III)-catalyzed C–H coupling of cyclic N-sulfonyl ketimines 100 and alkynes 101 to access benzosultams 102 by a formal [3+2] annulation reaction (Scheme 29).[34] Using a cationic [Cp*RhCl2]2/AgSbF6 catalyst system this reaction proceeded efficiently at room temperature when 10 mol % of Rh was employed; however, significant reduction in reaction rate was observed at lower catalyst loading unless reactions were carried out at higher temperatures or prolonged reaction times. As is typical of Rh(III) catalysis, good functional group tolerance was realized for the reacting C–H bond partner such that electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups could be placed at different positions of the aromatic ring. For the alkyne input 101, both aromatic and alkyl symmetrical internal derivatives were employed, and for unsymmetrical alkynes good yields were obtained although with modest regioselectivities. In a single example, reaction of a non-cyclic N-tosyl ketimine with diphenylacetylene gave aminoindene 105 in moderate yield (Scheme 29b).

Scheme 29.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Addition/Cyclization Cascade with N-Sulfonyl Ketimines and Alkynes

The following year, the same group developed a Rh(III)-catalyzed three-component coupling of cyclic N-sulfonyl ketimines 106, alkynes 107, and aldehydes 108 by arene C–H bond activation (Scheme 30).[35] Reaction optimization revealed that while acid additives promoted the formation of the three-component product 109, high yields were reproducibly obtained with (Boc)2O as reaction additive. The majority of the reaction scope was carried out using symmetrical diaryl alkynes, and use of an unsymmetrical diaryl derivative gave a mixture of regioisomers with very modest selectivity. When an aryl butyl alkyne was employed, a low yield of the three-component product was obtained along with the unreactive two-component product. A broad range of aldehydes 108 were effective substrates in the transformation, including electron-rich and electron-deficient aromatic, heteroaromatic, branched and linear alkyl derivatives, and ethyl glyoxylate. The only exception was for a pyridine-containing aldehyde that failed to participate in the reaction, likely due to the strong coordinating ability of the Lewis basic nitrogen that can bind to cationic Rh(III) to prevent catalysis.

Scheme 30.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Three-Component Coupling of Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Ketimines, Alkynes, and Aldehydes

3.2. Ru Catalysis

In 2012, Li and co-workers developed a Ru(II)-catalyzed annulative coupling of N-sulfonyl imines 110 and alkynes 111 to give aminoindenes 112 (Scheme 31).[36] Optimization experiments revealed that a cationic [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2/AgSbF6 catalyst system and the addition of a sulfonyl amine co-catalyst were critical toward achieving high yield. In contrast, use of analogous Rh(III) catalysts under identical conditions failed to promote the desired reactivity. Symmetrical diaryl and dialkyl alkynes coupled in moderate to good yield, although unsymmetrical alkynes provided a modest mixture of regioisomers. Terminal alkynes were not effective substrates; however, a trimethylsilyl alkyne was applied as a surrogate to give the desilylated product in good yield. A series of N-tosyl aldimines were employed and both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents could be placed at different positions of the aromatic ring. Other sulfonyl derivatives were also effective N-substituents, including an N-methanesulfonyl group. Notably, this transformation showcased the first example of an N-sulfonyl imine directing group in a C–H functionalization reaction.

Scheme 31.

Ru(II)-Catalyzed C–H Bond Cyclative Coupling of N-Sulfonyl Aldimines and Alkynes to Access Aminoindenes

In 2013, the Zhao laboratory detailed the synthesis of unprotected aminoindenes 116 via a Ru(II)/N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalyzed [3+2] carbocyclization reaction of aromatic N–H ketimines 113 and internal alkynes 114 (Scheme 32).[37] For the majority of substrates, use of a commercially available precatalyst [Ru(cod)(η3-methylallyl)2] in conjunction with the IPr ligand (115) in hexane allowed for clean conversion to the desired aminoindenes at ambient temperature. A series of diaryl ketimines were explored, including unsymmetrical diaryl derivatives that coupled in good yields but with modest regioselectivities. A butyl aryl N–H ketimine was also evaluated, but required use of the IMes ligand (117) and an increased reaction temperature of 60 °C. For unsymmetrical internal alkynes, good yields and regioselectivities were achieved for phenylacetylene derivatives bearing alkyl, alkenyl, or 2-thiophene functionalities.

Scheme 32.

Synthesis of Unprotected Aminoindenes by Ru-Catalyzed Coupling of N–H Ketimines and Internal Alkynes

In 2014, Gandeepan, Cheng, and co-workers reported on the synthesis of N-tosyl aminoindenes 120 by Ru(II)-catalyzed C–H bond activation (Scheme 33).[38] Although the overall transformation is redox neutral, the reaction did not proceed in the absence of two equivalents of Cu(OAc)·(H2O), and a significantly lower yield was obtained when only one equivalent was employed. Under the optimal reaction conditions, a series of N-tosyl benzaldimines substituted with electron-rich and electron-deficient functionalities were evaluated for reaction with diphenylacetylene. Both aryl and alkyl sulfonyl-protected aldimines were effective substrates, and in addition to aldimines, a ketimine C–H bond substrate also coupled in moderate yield. The authors also noted that neither N–H nor N–aryl imines coupled under the standard conditions. A variety of internal alkynes 119 were evaluated in the transformation. Symmetrical diaryl alkynes reacted cleanly, and for unsymmetrical derivatives, both aryl alkyl and aryl alkenyl alkynes provided good regioselectivities (≥ 7:1 rr).

Scheme 33.

Ru(II)-Catalyzed Synthesis of N-Sulfonyl Aminoindenes by a C–H Bond Addition/Annulation Cascade

3.5. Mn Catalysis

In 2015, the Ackermann laboratory developed a convergent synthesis of cis-β-amino acid derivatives 123 by Mn-catalyzed C–H activation/annulation cascades with enoates 122 (Scheme 34).[39] The transformation did not proceed with other earth-abundant catalysts such as Co2(CO)8 or Ni(cod)2. With respect to the imine C–H bond partner 121, a variety of substituted ketimines bearing both alkyl and aryl substituents at R2 coupled efficiently, although use of an aldimine provided only trace product. In several cases, imines with meta-substituted aryl groups provided a mixture of regioisomers. A range of acrylates 122 (R3 = H) were evaluated, as well as a crotonate 122(R3 = Me, R4 = Me) that allowed for the formation of three contiguous stereocenters. For all of the substrate combinations the reactions proceeded with high regio- and diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 34.

Diastereoselective Synthesis of cis-β-Amino Acid Derivatives by Mn-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization

3.4. Co Catalysis

As an extension to earlier reports that employed precious Rh catalysts, in 2016 Wang and co-workers published on an earth-abundant Co(III)-catalyzed synthesis of spiro indenyl benzosultams 126 (Scheme 35).[40] Effective coupling of the cyclic N-sulfonyl ketimine C–H bond partner 124 was highly dependent upon the steric and electronic properties of the R1 substituent. Electron-donating groups at the para or meta positions were beneficial and provided indenyl benzosultams in high yields, while electron-deficient groups reacted in only moderate or poor yields. However, even for electron-donating groups ortho substitution was highly detrimental. Diaryl and dialkyl symmetrical alkynes reacted efficiently, and an unsymmetrical internal alkyne provided a modest regioisomeric mixture of products. Interestingly, trimethylsilylacetylene provided the desired product in moderate yield as a single regioisomer, while no product was obtained for phenylacetylene.

Scheme 35.

Co(III)-Catalyzed C–H Addition/Annulation Cascade with Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Ketimines and Alkynes

3.6. Ir Catalysis

Building upon their earlier works on the Ir-catalyzed annulative coupling of boronic acids with 1,3-dienes, in 2013 Nishimura and co-workers developed a related strategy to access spiroaminoindanes 129 that employed Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H activation to catalytically generate a reactive organometallic nucleophile (Scheme 36).[41] Using cyclic N-sulfonyl ketimines 127 as the directing group this reaction proceeds with high diastereo- and regiocontrol with only a single isomer detected. In their evaluation of different reaction conditions, the authors found that catalytic amounts of both a noncoordinating BArF4 counterion and the organic base DABCO were essential to achieving efficient reactivity. The substrate scope of this reaction was carried out with a range of cyclic N-sulfonyl ketimines 127 and functionalized dienes 128. For the imine partner electron-rich, electron-neutral, and electron-deficient functionalities were well tolerated. Dienes bearing alkyl, aryl, and electron-withdrawing groups were shown to react in good yield and with high regioselectivity.

Scheme 36.

Diastereoselective Synthesis of Spiroaminoindanes by Ir(III)-Catalyzed Coupling of Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Ketimines and Dienes

The same group later published a full paper in which they expanded the scope of this chemistry to include acyclic N-sulfonyl imines and a variety of substituted dienes (Scheme 37).[42] In contrast to their earlier report, this transformation did not require the use of a cationic catalyst system, and the addition of potassium acetate as an additive provided a significant improvement in yield. Notably, use of other inorganic bases such as K3PO4, K2CO3, or NaOAc provided either very low yields or no reaction, and employing [RhCl(coe)2]2 under the optimal conditions provided none of the desired product. In this study, cyclic dienes were also employed to provide entry to fused carbocyclic products. Mechanistic experiments included the determination of an intermolecular kinetic isotope effect (KIE) as well as a series of competition experiments to evaluate the effect of electronics on the rate of product formation. Unlike their earlier study using a cationic Ir(I) catalyst system, for the current transformation with noncationic [IrCl(coe)2]2/KOAc, the authors suggest a concerted metalation deprotonation (CMD) pathway for C–H bond activation.

Scheme 37.

Ir(I)-Catalyzed Coupling of N-Sulfonyl Ketimines and Dienes by C–H Activation

In 2014, Nishimura and co-workers developed a method to access aminoindenes by an Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H functionalization/cyclization cascade (Scheme 38).[43] In this study the authors directly employed hemiaminal C–H bond substrates 133 to allow for in situ generation of the corresponding N-acylketimine directing group by dehydration (Scheme 38a). On the other hand, N-sulfonyl ketimines 136 could be used directly in the reaction, and both cyclic and N-tosyl variants were shown to be effective (Scheme 38b). With respect to the alkyne coupling partner, the majority of scope was carried out using internal substrates, including electron-rich and electron-deficient diaryl derivatives and 4-octyne. Unsymmetrical alkynes coupled with low regioselectivity; however, coupling to terminal silyl alkynes provided products as single regioisomers, albeit in low yields.

Scheme 38.

Ir(I)-Catalyzed C–H Addition/Annulation Cascade with N-acyl hemiaminals and N-Sulfonyl Ketimines

4. Asymmetric C–H Bond Addition to Imines

4.1. Rh Catalysis

In 2011, the Cramer laboratory developed an enantioselective strategy to access aminoindenes 142 by a Rh(I)-catalyzed annulative C–H functionalization of N–H ketimines 139 with internal alkynes 140 (Scheme 39).[44] Of the various Rh(I) catalysts that were screened neither cationic nor halide-containing complexes promoted the desired reactivity. Only oxyanion containing complexes showed catalytic activity, and hydroxide ions provided the highest reaction conversion and enantioselectivity. Furthermore, premixing of the [Rh(coe)2(OH)]2 precatalyst and phosphine ligand (S)-141 allowed for improved reaction yield. The scope of this transformation was carried out with a variety of functionalized N–H ketimines and internal alkynes. When unsymmetrical diaryl ketimines were employed C–H functionalization primarily occurred on the more electron-deficient aromatic ring, a trend that was maintained for a pyridine-containing C–H partner. Unsymmetrical alkynes containing coordinating groups allowed for regioselective insertion proximal to the directing functionality. Terminal or electron-deficient alkynes did not participate in the reaction.

Scheme 39.

Asymmetric Synthesis of Aminoindenes by Rh(I)-Catalyzed Coupling of N-H Ketimines and Internal Alkynes

In 2014, our laboratory published the first examples of the intermolecular asymmetric addition of non-acidic C–H bonds to imines (Scheme 40).[45] Given that N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines are versatile and extensively used intermediates for the asymmetric synthesis of amines, we envisioned that the use of these substrates would provide a straightforward way to realize transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric C–H bond additions.[1c,d] While no product was observed during our initial evaluation of Rh(III)-catalyzed asymmetric C–H bond additions to N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines, additions to highly activated N-perfluorobutanesulfinyl imines 144 gave α-branched amines 145 with excellent diastereoselectivities. Employing a synthetically useful amide directing group, asymmetric C–H bond additions were demonstrated for a series of substituted aldimines containing both electron-withdrawing and electron-donating functionalities. Aromatic C–H functionalization was also shown to be efficient for a 2-quinoline directing group, and in all cases reactions proceeded with uniformly high diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 40.

Rh(III)-Catalyzed Asymmetric C–H Bond Addition to N-Perfluorobutanesulfinyl Aromatic Aldimines

In a subsequent paper, we then expanded the scope and versatility of this strategy, by focusing our efforts on Rh(III)-catalyzed asymmetric C–H bond additions to N-perfluorobutanesulfinyl imino esters 147 to furnish arylglycines 148 (Scheme 41).[46] The scope of this reaction was explored with a range of directing groups for C–H functionalization including pyrrolidine amide, azo, sulfoximine, 1-pyrazole, and 1,2,3-triazole functionalities. In all cases the reactions proceeded with very high diastereoselectivity. The sense of induction was also established by X-ray crystal structure determination of one of the addition products. Even for the highly epimerizable arylglycines that were obtained, facile removal of the N-perfluorobutanesulfinyl group was achieved via treatment with HCl in methylene chloride at ambient temperature to give the corresponding amine hydrochloride in good yield and without any loss in stereochemical purity.

Scheme 41.

Asymmetric Arylglycine Synthesis by Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization

4.2. Pd Catalysis

In 2012, Lam and co-workers detailed a strategy for Pd-catalyzed asymmetric additions of acidic C(sp3)–H bonds to Boc-protected imines 150 (Scheme 42).[47] This transformation showcased the first catalytic enantio- and diastereoselective C–H bond additions of 2-alkyl azaarenes 149 to imines, and under practical conditions using a chiral Pd(II)-bis(oxazoline) catalyst that operated at ambient temperature or with mild heating under an air atmosphere with undried solvent. To achieve the desired reactivity, it was necessary to install acidifying groups such as nitro, ester, and cyano substituents on aromatic ring of the reacting C–H bond substrate. For benzoxazoles several functional groups were tolerated at the reacting α-position including aliphatic, benzyl, and methoxy substituents (Scheme 42a). Functionalization of a 5-nitrobenzothiazole was also shown, as were several examples using 3-nitropyridines (Scheme 42b). Asymmetric C–H bond additions were demonstrated for both electron-neutral and electron-deficient N-Boc imines. Further synthetic application was also achieved by C(sp3)–H bond additions to nitroalkenes. Notably, no examples were provided in the current study for asymmetric C–H functionalization for azaarenes lacking acidifying groups; however, a single example of Pd-catalyzed asymmetric C(sp3)–H bond addition of 2,6-lutidine to an N-tosyl aldimine was later reported by Beletskaya and co-workers, albeit in only modest yield and enantiomeric excess.[48]

Scheme 42.

Pd(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric C(sp3)–H Bond Addition of 2-Alkyl Azaarenes to Boc-Protected Aldimines

4.3. Ir Catalysis

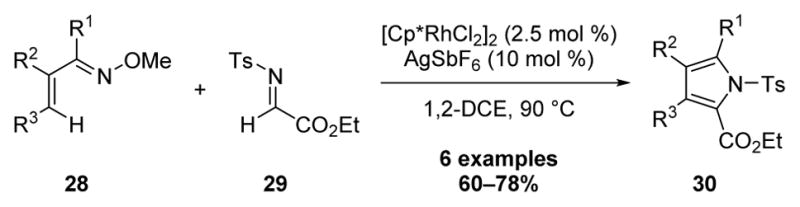

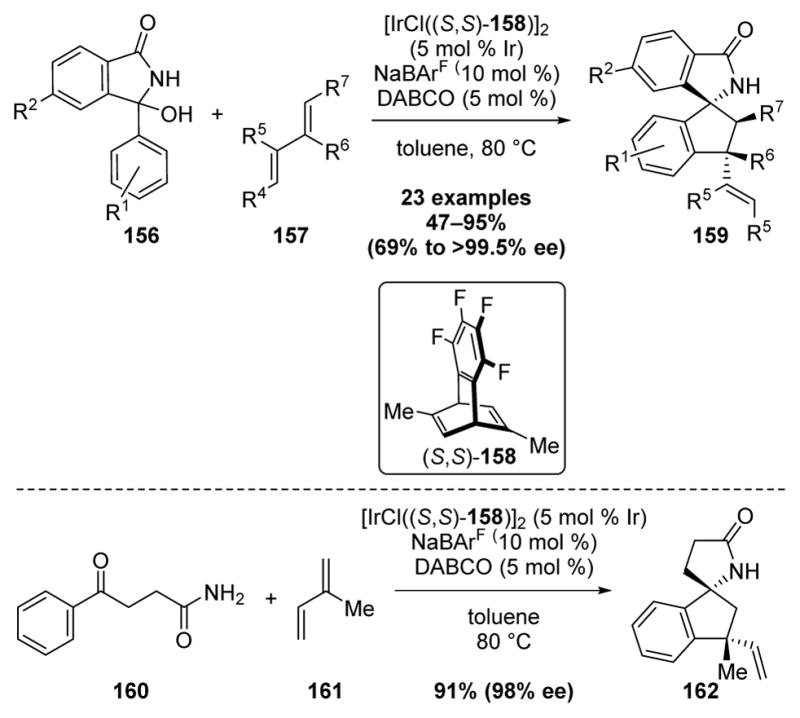

In 2013, the Nishimura laboratory reported an Ir(I)-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of spiroaminoindanes 159 by a C–H bond addition/annulation reaction (Scheme 43).[49] Building upon an earlier study employing N-sulfonyl ketimines and dienes (vide supra), initial evaluation of an asymmetric transformation using this system with chiral diene ligand (S, S)-158 provided a low yield of the desired aminoindane. In contrast, in situ generation of N-acyl ketimines from hemiaminals 156 provided high yields of spiroaminoindanes 159 with excellent enantioselectivity when [IrCl((S, S)-158)]2 was used as catalyst in conjunction with a NaBArF4 counterion and catalytic DABCO. Use of other chiral diene ligands, binap, and a phosphoramidite resulted in significant reduction in reaction enantioselectivities and yields. Notably, linear γ-keto amide 160 was also an efficient substrate under the optimal reaction conditions, furnishing spiroaminoindane 162 in 91% yield and 98% enantiomeric excess.

Scheme 43.

Ir(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of Spiroaminoindanes by C–H Functionalization

4.4. Co Catalysis

Very recently, our laboratory developed a Co(III)-catalyzed asymmetric C–H bond addition cascade employing N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines 165 (Scheme 44).[50] Using preformed cationic catalyst 166, three-component C–H bond additions were demonstrated for both an N-sulfinyl trifluoroacetaldimine and an N-sulfinyl imino ester to provide α-branched amines in good yield and with high diastereoselectivity. These examples represent the first Cp*Co(III)-catalyzed asymmetric reactions and are the seminal examples of additions to N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines by transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond activation.

Scheme 44.

Co(III)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Three-Component C–H Bond Addition Cascade with N-tert-Butanesulfinyl Imines

5. Summary

Transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines provide a convergent and efficient approach for the synthesis of a diverse array of α-branched amines as well as nitrogen heterocycles. Using readily available C–H bond inputs, these transformations provide a convenient and atom-economic approach for the catalytic generation of organometallic nucleophiles to complement the use of more traditional prefunctionalized organometallic inputs. Transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond additions to imines typically proceed without the need for strongly acidic or basic additives, and typically avoid the formation of waste byproducts. Furthermore, many of the transition-metal catalysts used for C–H bond additions to imines display high functional group compatibility. In addition, a number of processes have been developed that proceed via cascade cyclization pathways to provide rapid entry into amine-substituted carbocycles, often with the generation of two or more contiguous stereocenters. Recently, progress has also been achieved toward asymmetric C–H bond additions to imines through the use of chiral imine N-substituents as well as by enantioselective catalysis. We anticipate that future advances in this area will focus on the development of novel applications and asymmetric reactions, as well as the design of more efficient and selective ligands and transition-metal catalysts.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the NIH (R35GM122473).

Biographies

Dr. Jonathan A. Ellman is the Eugene Higgins Professor of Chemistry and Professor of Pharmacology at Yale University. Ellman earned his B.S. degree from MIT and his Ph.D. degree from Harvard University. He completed his postdoctoral research at UC Berkeley. Prior to moving to Yale in 2010, he was a member of the faculty at UC Berkeley where he held the rank of Professor of Chemistry from 1999 to 2010 and concurrently was appointed Professor of Cellular and Molecular Biology at UC San Francisco. Ellman has received a number of awards for his research. These include the Royal Society of Chemistry Pedler Award and the American Chemical Society Herbert C. Brown Award for Creative Research in Synthetic Methods. He has been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Joshua R. Hummel was born and raised in Exeter, PA. In 2012, he received his B.S. degree from Temple University where he carried out research in the laboratory of Professor Franklin A. Davis. Under the direction of Professor Jonathan A. Ellman he earned his Ph.D. from Yale University in 2017. His research in the Ellman laboratory focused on the development of new synthetic methods for Rh(III)- and Co(III)-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization. Currently, he is working as a medicinal chemist at Incyte Corporation.

Footnotes

Dedicated to 2017 Wolf Prize Awardee Professor Robert G. Bergman

References

- 1.(a) Tian P, Dong HQ, Lin GQ. ACS Catal. 2012;2:95–119. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi S, Mori Y, Fossey JS, Salter MM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:2626–2704. doi: 10.1021/cr100204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Robak MT, Herbage MA, Ellman JA. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3600–3740. doi: 10.1021/cr900382t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ferreira F, Botuha C, Chemla F, Perez-Luna A. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1162–1186. doi: 10.1039/b809772k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yamada K, Tomioka K. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2874–2886. doi: 10.1021/cr078370u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For reviews that emphasize transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond additions to polarized π bonds, see: Hummel JR, Boerth JA, Ellman JA. Chem Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00661. Article ASAP.Yang L, Huang H. Chem Rev. 2015:3468–3517. doi: 10.1021/cr500610p.Zhang XS, Chen K, Shi ZJ. Chem Sci. 2014;5:2146–2159.Yan GB, Wu XM, Yang MH. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:5558–5578. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40652k.

- 3.Hyster TK, Knörr L, Ward TR, Rovis T. Science. 2012;338:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1226132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Bisai V, Singh VK. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:4771–4784. [Google Scholar]; (b) Peshkov VA, Pereshivko OP, Van der Eycken EV. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3790–3807. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15356d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoo WJ, Zhao L, Li CJ. Aldrichimica Acta. 2011;44:43–51. [Google Scholar]; (d) Li CJ. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:581–590. doi: 10.1021/ar9002587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai AS, Tauchert ME, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1248–1250. doi: 10.1021/ja109562x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tauchert ME, Incarvito CD, Rheingold AL, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1482–1485. doi: 10.1021/ja211110h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2009;28:3492–3500. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Li BJ, Wang WH, Huang WP, Zhang XS, Chen K, Shi ZJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2115–2119. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Zhang XS, Li H, Wang WH, Chen K, Li BJ, Shi ZJ. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1634–1639. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesp KD, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Org Lett. 2012;14:2304–2307. doi: 10.1021/ol300723x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Zhang XS, Zhu QL, Shi ZJ. Org Lett. 2012;14:4498–4501. doi: 10.1021/ol301989n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou B, Yang Y, Lin S, Li Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2013;355:360–364. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parthasarathy K, Azcargorta AR, Cheng Y, Bolm C. Org Lett. 2014;16:2538–2541. doi: 10.1021/ol500918t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lian Y, Huber T, Hesp KD, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:629–633. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boerth JA, Ellman JA. Chem Sci. 2016;7:1474–1479. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04138d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao K, Yoshikai N. Chem Commun. 2012;48:4305–4307. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31114c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao K, Yoshikai N. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:1208–1219. doi: 10.1021/ar400270x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshino T, Ikemoto H, Matsunaga S, Kanai M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:2207–2211. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshino T, Ikemoto H, Matsunaga S, Kanai M. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:9142–9146. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian B, Guo S, Shao J, Zhu Q, Yang L, Xia C, Huang H. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3650–3651. doi: 10.1021/ja910104n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian B, Guo S, Xia C, Huang H. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:3195–3200. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rueping M, Tolstoluzhsky N. Org Lett. 2011;13:1095–1097. doi: 10.1021/ol103150g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komai H, Yoshino T, Matsunaga S, Kanai M. Synthesis. 2012;44:2185–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian B, Xie P, Xie Y, Huang H. Org Lett. 2011;13:2580–2583. doi: 10.1021/ol200684b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Kuninobu Y, Kawata A, Takai K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005:13498–13499. doi: 10.1021/ja0528174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuninobu Y, Tokunaga Y, Kawata A, Takai K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006:202–209. doi: 10.1021/ja054216i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuninobu Y, Nishina Y, Shouho M, Takai K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2766–2768. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuninobu Y, Nishina Y, Okaguchi K, Shouho M, Takai K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2008;81:1393–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuninobu Y, Yu P, Takai K. Org Lett. 2010;12:4274–4276. doi: 10.1021/ol101627x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin X, Yang X, Yang Y, Wang C. Org Chem Front. 2016;3:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukutani T, Umeda N, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Chem Commun. 2009:5141–5143. doi: 10.1039/b910198e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han YF, Li H, Hu P, Jin GX. Organometallics. 2011;30:905–911. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun ZM, Chen SP, Zhao P. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:2619–2627. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran DN, Cramer N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8181–8184. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong L, Qu CH, Huang JR, Zhang W, Zhang QR, Deng JG. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:16537–16540. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang JR, Song Q, Zhu YQ, Qin L, Qian ZY, Dong L. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:16882–16886. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao P, Wang F, Han K, Li X. Org Lett. 2012;14:5506–5509. doi: 10.1021/ol302594w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Ugrinov A, Zhao P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:6681–6684. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung CH, Gandeepan P, Cheng CH. ChemCatChem. 2014;6:2692–2697. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W, Zell D, John M, Ackermann L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:4092–4096. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H, Li J, Xiong M, Jiang J, Wang J. J Org Chem. 2016;81:6093–6099. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura T, Ebe Y, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2092–2095. doi: 10.1021/ja311968d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebe Y, Hatano M, Nishimura T. Adv Synth Catal. 2015;357:1425–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagamoto M, Nishimura T. Chem Commun. 2014;50:6274–6277. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01874e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tran DN, Cramer N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11098–11102. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wangweerawong A, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:8520–8523. doi: 10.1021/ja5033452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wangweerawong A, Hummel JR, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Org Chem. 2016;81:1547–1557. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Best D, Kujawa S, Lam HW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18193–18196. doi: 10.1021/ja3083494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patrikeeva LS, Beletskaya IP. Russ Chem Bull. 2014;63:2686–2688. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishimura T, Nagamoto M, Ebe Y, Hayashi T. Chem Sci. 2013;4:4499–4504. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boerth JA, Hummel JR, Ellman JA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:12650–12654. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]