Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Parental alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and parental separation are associated with increased risk for early use of alcohol in offspring, but whether they increase risks for early use of other substances and for early sexual debut is under-studied. We focused on associations of parental AUDs and parental separation with substance initiation and sexual debut to (1) test the strength of the associations of parental AUDs and parental separation with time to initiation (age in years) of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use, and sexual debut, and (2) compare the strength of association of parental AUD and parental separation with initiation.

DESIGN

Prospective adolescent and young adult cohort of a high-risk family study, the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA).

SETTING

6 sites in the United States.

PARTICIPANTS

3527 offspring (ages 14–33) first assessed in 2004 and sought for interview approximately every 2 years thereafter. 1945 (59.7%) offspring had a parent with an AUD.

MEASUREMENTS

Diagnostic interview data on offspring substance use and sexual debut were based on first report of these experiences. Parental lifetime AUD was based on their own self-report when parents were interviewed (1991–2005) for most parents, or on offspring and other family member reports for parents who were not interviewed. Parental separation was based on offspring reports of not living with both biological parents most of the time between ages 12 and 17 years.

FINDINGS

Parental AUDs were associated with increased hazards for all outcomes, with cumulative hazards ranging from 1.2 to 2.7. Parental separation was also an independent and consistent predictor of early substance use and sexual debut, with hazards ranging from 1.2 to 2.3. The strength of association of parental separation with substance initiation was equal to that of having 2 AUD-affected parents, and its association with sexual debut was stronger than parental AUD in one or both parents.

CONCLUSIONS

Parental alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and parental separation are independent and consistent predictors of increased risk for early alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use and sexual debut in offspring from families with a high risk of parental AUDs.

Keywords: COGA, alcohol use disorders, cannabis, sexual debut, tobacco, parent AUD, familial, early substance use

INTRODUCTION

Early initiation of substance use is associated with many negative outcomes, including increased risk for developing substance use disorders (1–6), lower educational attainment (7, 8), early sexual debut, and risky sexual behaviors (9–11). Age at onset of alcohol, cigarette, and cannabis use is influenced by genetic and familial environmental factors (12, 13), some of which are common across substances (3, 14). A recent twin study found that a common factor accounted for 15% – 43% of the genetic influences on age at initiation of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis, and also contributed 18% to 77% of the shared environmental variance in initiation of each substance, suggesting that the family environment plays a significant role in age at initiation of multiple substances (14). Parental alcohol use disorders (AUDs) affect the family environment shared by offspring in multiple ways that increase the likelihood of early substance use. In households where one or both parents has an AUD, there is a greater incidence of parental separation (15, 16), childhood trauma (15, 17), and decreased parental monitoring of child behavior (18, 19), factors which have also been associated with earlier ages at first drink (1, 16, 20), first cigarette, first use of cannabis (20), and earlier age at sexual debut (21). Parental separation in particular is a potent factor related to early age at first substance use (20, 22, 23) and sexual debut (21) even after adjustment for parental AUD. While parental AUDs are associated with earlier age at initiation of alcohol use (16, 24–28), few studies examine whether they also increase risk for early use of other substances and other risky behaviors (29, 30) or adjust for the strong effect of parental separation on early initiation (20–23). In the current study, we focus on associations of parental AUDs and parental separation with substance initiation and sexual debut to (1) test the strength and independence of the associations of parental AUDs and parental separation with time to initiation of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use, and sexual debut, and (2) compare the strength of association of parental AUD and parental separation with initiation.

METHODS

Design

The outcomes were time, in years since birth, to initiation of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use and to sexual debut. The joint associations of parental AUDs and parental separation with each of the outcomes were first tested to determine their independence and strength, then compared to determine their relative strength for each outcome.

Sample

Data were from participants in the ongoing prospective cohort of the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA), a multi-site family study which began in 1989 with the purpose of identifying genes that increase the risk for AUDs. Families were identified through probands in treatment for alcoholism at 6 sites in the U.S. Probands and their first-degree relatives were interviewed with a comprehensive, structured interview, the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) (31, 32), and in families where 2 or more first-degree relatives were also affected, additional branches of the family were recruited to the study. Comparison families recruited from a variety of sources (e.g., dental clinics, drivers’ registries) participated in the same protocol. Because these families were intended to represent a subset of the general population, family members were not excluded if they met criteria for an AUD or other psychiatric disorder. Further details about the study have been published (33, 34).

The prospective component of the COGA study began in 2004 and is ongoing (35). Offspring from high risk and comparison families who are aged 12–22 (born 1982 or later) at intake, and who have at least one parent who was interviewed for the COGA study (1991–2005), are enrolled, with new subjects added as they reach the age of 12. Subjects are interviewed every two years with the SSAGA or, for subjects younger than 18, the childhood version (C-SSAGA), which covers alcohol and other substance use problems and disorder and other psychiatric disorders (36). This study focused on 3257 offspring from 1912 nuclear families with 1 (51.9%), 2 (31.8%) or 3 or more (16.3%) participating offspring as of June, 2016 who had data on both parents. The dataset included 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 year follow-up data for 2851, 2337, 1812, and 1153 and 442 individuals, respectively. Sixty-four percent of the sample had 3 or more follow-up interviews, 16.4% had 2, 15.7% had 1, and 12.4% had not yet had a follow-up interview. Sample demographics are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, parental separation, and substance use characteristics of 3257 offspring overall and by parental AUD status.

| Parental AUD Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | None | One parent only AUD | Both Parents AUD | 1 parent AUD possible, co-parent unaffected | Test of differences by parental AUD status | |

|

| ||||||

| N=3257 | N=1160 | N=1273 | N=672 | N=152 | Design-based statistic and p-value | |

| Female,% | 51.1 | 50.8 | 51.0 | 51.5 | 53.3 | F(3, 5726)=.13, p=.94 |

| European American, % | 65.9 | 64.4 | 63.8 | 76.0 | 50.0 | F(6, 1906)=4.9, p<.001 |

| African American, % | 25.8 | 27.2 | 28.4 | 15.8 | 37.5 | |

| Other race/ethnicity, % | 8.3 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 12.5 | |

| Age at study entry, M(SD, range) | 16.1 (3.3, 12–26) | 15.8 (3.3, 12–24) | 16.4 (3.3, 12–26) | 16.2 (3.3, 12–25) | 15.7 (3.2, 12–25) | F(3, 1909)=6.7, p<.001 |

| Age at most recent follow-up, M(SD, range) | 22.8 (4.5, 14–33) | 22.5 (4.6, 14–33) | 23.1 (4.4, 14–32) | 22.7 (4.4, 14–32) | 22.1 (4.4, 13–31) | F(3, 1704)=3.2, P=.02 |

| Parental separation, % | 47.9 | 32.5 | 54.5 | 56.8 | 73.3 | F(3, 1900)=34.8, p<.0001 |

| Ever had drink alcohol, % | 82.5 | 75.6 | 87.3 | 85.4 | 81.6 | F(3, 1909)=13.44, p<.0001 |

| Ever smoked full cigarette, % | 48.3 | 36.6 | 52.2 | 61.8 | 46.0 | F(3, 1909)=28.6, p<.0001 |

| Ever used cannabis, % | 65.1 | 54.5 | 71.1 | 71.0 | 70.4 | F(3, 1909)=20.8, p<.0001 |

| Ever had voluntary sexual intercourse, % | 79.3 | 72.4 | 83.4 | 82.9 | 81.6 | F(3, 1909)=11.2, p<.0001 |

| Timing of first substance use, sexual debut | ||||||

| Age first drink, M (SD, range) | 15.7 (2.5, 7–30) | 16.3 (2.5, 7–30) | 15.6 (2.5, 7–25) | 15.1 (2.5, 7–26) | 15.6 (2.5, 8–22) | F(3, 1680)=16.3, p<.0001 |

| First drink ≤ age 15, % | 38.7 | 29.2 | 41.3 | 49.5 | 40.1 | |

| First drink ≥ age 16, % | 43.8 | 46.4 | 46.0 | 35.9 | 41.5 | |

| Age first cigarette, M (SD, range) | 15.6 (3.0, 7–30) | 16.2 (2.6, 9–24) | 15.7 (3.0, 7–28) | 15.0 (3.1, 7–30) | 15.3 (3.1, 8–24) | F(3, 1139)=9.6, p<.0001 |

| First cigarette ≤ age 15, % | 23.5 | 14.3 | 25.1 | 36.1 | 25.6 | |

| First cigarette ≥ age 16, % | 24.8 | 22.3 | 27.1 | 25.7 | 20.4 | |

| Age first use cannabis, M (SD, range) | 15.9 (2.7, 8–29) | 16.5 (2.7, 8–27) | 15.9 (2.7, 8–29) | 15.4 (2.8, 8–26) | 15.8 (2.6, 8–23) | F(3, 1436)=12.5, p<.0001 |

| First cannabis ≤ age 15, % | 29.5 | 19.8 | 33.6 | 37.3 | 34.9 | |

| First cannabis ≥ age 16, % | 35.6 | 34.7 | 37.5 | 33.6 | 35.5 | |

| Age sexual debut, M (SD, range) | 16.3 (2.3, 10–27) | 16.9 (2.5, 10–27) | 16.1 (2.2, 10–25) | 15.8 (2.1, 10–24) | 15.7 (2.0, 10–22) | F(3, 1657)=21.3, p<.0001 |

| First sex ≤ age 15, % | 30.0 | 20.8 | 33.8 | 36.5 | 39.5 | |

| First sex ≥ age 16, % | 49.3 | 51.6 | 49.6 | 46.4 | 42.1 | |

Measures

Outcomes: Offspring substance use and sexual debut

Data from all offspring interviews were used to obtain lifetime reports of substance use and consensual sexual debut; age at onset for each behavior was based on first report. For subjects who had already initiated a particular substance or sexual debut at the baseline interview or had only one interview (52.9%), retrospectively-reported age at first use or first sex was used. Age was recorded in years since birth, in yearly increments. Substance use variables came from the alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco assessments of the SSAGA and C-SSAGA interviews, and sexual debut from a question in the antisocial behaviors section about age at first sexual intercourse. Subjects were first asked “Have you ever had sexual intercourse voluntarily?”, and if “yes”, “How old were you when you first had sexual intercourse (voluntarily)?”

Independent variables: Parental AUD status and parental separation

Parental AUD was a lifetime measure based on parents’ self-report from direct diagnostic SSAGA interviews when available (65.3% of fathers and 90.5% of mothers). For parents who were not interviewed, at least 2 positive family history reports, based on the Family History Assessment Module (37), were used to code parents as affected (5.1% of fathers and 0.3% of mothers). If fewer than 2 family history reports were available, parents were coded as “possible AUD” if there was just 1 positive family history report (5.9% of fathers and 0.9% of mothers) or if offspring reported that the parent was a heavy drinker or recovering alcoholic in the Important People and Activities interview (38) (2.3% of fathers and 1.1% of mothers). The combined AUD status of both parents was represented with dummy variables coded 0/1 for father only AUD, mother only AUD, both parents AUD, and 1 parent negative and other parent possible AUD. (see Supplemental Table 1 for details on parental AUD coding). Parental separation was represented by a dummy variable coded 1 for offspring who reported they did not live with both biological parents most of the time between ages 12 and 17 years, and 0 for all others.

Control variables

Internalizing (any among major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, or suicidal ideation) and externalizing (either conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder) domains based on offspring data about DSM-IV lifetime criteria (39) from the SSAGA interviews were included to account for potential effects of self-medication on substance use (40, 41) and associations of externalizing and internalizing problems with sexual debut (42) and with parental AUDs (43, 44). Assaultive and non-assaultive trauma variables were based on a trauma screen which preceded the posttraumatic stress disorder section of the interview. Based on evidence that interpersonal assaultive events have a stronger and more enduring effect on psychopathology and substance use than nonassaultive events (45–49), and that traumatic events cluster together (50), we created two composite variables representing report of one or more lifetime assaultive traumas (stabbed, shot, mugged, threatened with a weapon, robbed, kidnapped, held captive, raped or molested) and nonassaultive traumas (life-threatening accident, disaster, witnessing someone seriously injured or killed, and unexpectedly finding a dead body). The earliest reported age of occurrence of an internalizing or externalizing disorder or traumatic event was selected to represent age at onset of the respective composite variable. These control variables were modeled as time-varying (i.e., coded “0” before onset and “1” during year of onset and thereafter), so that only disorders or events that preceded or occurred at the same time as the outcome contributed to risk. Demographic control variables were yearly family income (low [<$30,000], middle [referent], high [≥$75,000]), sex, ethnicity (African American and other versus European American), case family (versus comparison), and birth cohort. Age in years is implicit in the models where interactions with age were necessary to satisfy the proportional hazards assumption, described below in statistical methods.

Statistical methods

First, we estimated frequencies of parental separation, substance use, and sexual debut, and average age at initiation of each substance and at sexual debut, in the sample as a whole and as a function of parental AUD status. Second, we used survival analysis to estimate the strength of association of parental separation and parental AUDs with each of the 4 outcomes: time in years since birth to initiation of alcohol, cigarette, and cannabis use, and sexual debut. Within this step, we (i) used Cox regression to test the associations of mother-only and father-only AUD with each outcome, then performed post-hoc Wald chi-square tests to assess the equality of the coefficients. Since the coefficients for mother-only and father-only AUD did not differ for any outcome (p-values ranging from .17 to .94), we combined them into a single variable representing alcohol problems in either parent; (ii) graphed cumulative failure rates using the Kaplan-Meier survival function. Third, we estimated Cox proportional hazards regression models predicting age at first use of alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis, and age at sexual initiation from parental AUD (modeled with 3 dummy variables representing AUD in one parent, both parents, or possible AUD in one parent) and parental separation, before and after adjustment for control variables. Observations were censored at first use of substance or first sex; subjects who had not yet used substances or had sex were censored at their most recent age. Fourth, we performed post-hoc Wald chi-square tests to compare the relative strength of association with each outcome of parental separation with AUD in one parent and AUDs both parents. Significance for p-values was adjusted for multiple testing (p=.05/2 tests =.025). Tests of proportional hazards, i.e. the assumption that the risk associated with different levels of a variable remain proportional over time, were computed using Schoenfeld residuals (51). Where such variations in risk were found for parental AUDs and parental separation, interactions with age that correspond to key developmental periods were created and entered into the model (i.e., early childhood [12 and younger], puberty [13–15], early adolescence (16–18), and young adulthood [19 and older]) (52). For example, subjects with 2 AUD-affected parents may have greater cumulative incidence of alcohol initiation before age 16 than later, and that difference in cumulative incidence before and after age 16 is modeled with an age interaction (see Supplemental Figure 1 for visual representation). For control variables, the average association with the outcome across time was used, since violations of the proportional hazards assumption did not affect the interpretation of the association of parental AUDs and parental separation outcomes (53, 54). Standard errors were adjusted for the non-independence of observations within families using the Huber-White robust variance estimator, and analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software Release 14 (55).

RESULTS

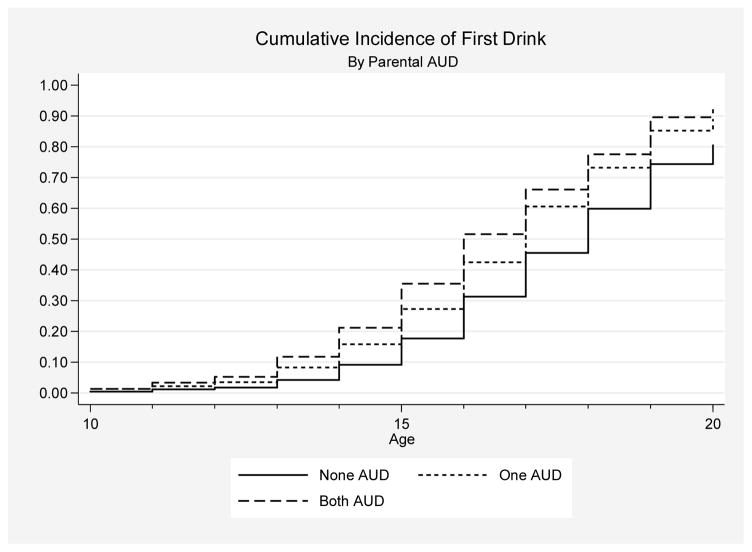

Nearly 60% of the sample had at least one parent with an AUD (39.1% one parent, 20.6% both parents), and an additional 4.7% had one parent with possible AUD. Rates of AUDs among fathers and mothers, respectively, were 41.8% and 33.0%. Among offspring with just one affected parent, AUD was more prevalent in fathers (64.6%) than mothers (35.4%). Table 1 contains demographics, rates of parental separation, and substance use variables for the sample as a whole and by parental AUD status (see Supplemental Table 2 for all covariates). In general, age at initiation of substance use and sexual debut were youngest among subjects with 2 AUD-affected parents, slightly older among subjects with 1 affected or possibly affected parent and oldest among subjects with no parental AUDs. This gradation by parental AUDs is apparent for alcohol initiation in Figure 1 (see Supplemental Figures 2–8 for other outcomes).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of first drink, by parental AUD

Survival analysis results

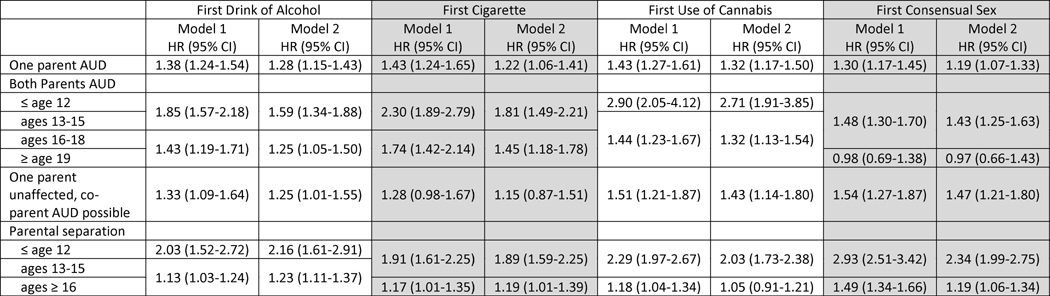

Parental AUDs and parental separation were associated with initiation of each of the substances and with sexual debut in unadjusted models and in models adjusted for control variables (Table 2, see Supplemental Table 3 for bivariate associations). Results from Table 2 adjusted models are discussed below.

Table 2.

Associations of parental AUD with time in years from birth to offspring first use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and sexual debut.

HR=hazard ratio; “ ≤ age 12” and other age notations indicate that interactions with age were modeled because the hazard associated with parental AUD or parental separation varied significantly with offspring age (e.g., parental separation was associated with greater risk for first drink at age 12 and younger [HR=2.16] than at age 13 and older [HR=1.23]). Model 1 is unadjusted, Model 2 adjusted for externalizing (CD or ODD), internalizing/suicidality (lifetime major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, suicidal ideation), assaultive trauma (one or more of stabbed, shot, mugged, kidnapped/held captive, threatened with a weapon, robbed), nonassaultive trauma (one or more of life-threatening accident, disaster, witnessing someone seriously injured or killed, and unexpectedly finding a dead body), family income, sex, race/ethnicity, case status of family, birth cohort. Results with all control variables are available in Supplemental Table 3.

Parental AUDs

The hazard associated with having one parent with an AUD (versus no parental AUD) was similar across all ages and was associated with all outcomes. In adjusted models, the increased risk associated with having one parent with an AUD, versus none, ranged from 20% for age at first consensual sex (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.19) to 32% for age at first use of cannabis (HR=1.32). The hazards associated with having one parent with possible AUD were similar to the hazards associated with having one parent with diagnostic AUD in regard to alcohol and cannabis initiation and sexual debut.

Having two AUD-affected parents had a stronger association with risk for early than later initiation for all outcomes. AUD in both parents had a stronger association with risk for use of alcohol and cigarettes before age 16 than later (alcohol: HRs=1.59 and 1.25; cigarettes: HRs=1.81 and 1.45). For first use of cannabis, having two parents with an AUD was more strongly associated with beginning use at age 12 and younger than later (HRs=2.71 and 1.32). Regarding first consensual sex, having 2 AUD-affected parents was associated with a stable 43% increased risk until age 18, after which there was no significant association (HRs=1.43 and 0.97).

Parental separation

Parental separation, like parental AUDs, was more strongly associated with early than later age at initiation. Subjects who did not grow up with both biological parents, compared to those who did, were at increased risk for first use of alcohol before age 13 (HR=2.16) and for initiating cigarette and cannabis use before age 16 (HRs=1.89 and 2.03, respectively), as well as increased risk for sexual debut before age 16 (HR=2.34).

Relative strength of associations of parental AUD and parental separation

To determine the relative strengths of association of parental AUDs and parental separation, we used post-hoc Wald tests to compare the largest hazard associated with parental separation (i.e., the younger age categories) with (1) the hazard associated with one parent with an AUD and (2) the hazard associated with 2 AUD-affected parents for the youngest age category, for all outcomes. Parental separation had a stronger association with first use of alcohol than did having one parent with an AUD (HRs=2.16 versus 1.28, Wald χ2(1)=10.7, p<.01) but did not differ from the hazard associated with 2 affected parents (HRs=2.16 versus 1.59, χ2(1)=3.1, p=08). This pattern was also observed for tobacco and cannabis, where parental separation had a significantly stronger association with initiation risk than did having one AUD-affected parent, and had risk equivalent to that of having 2 AUD-affected parents (tobacco: HRs=1.89 versus 1.22, χ(1)=13.0, p<.001 and HRs= 1.89 and 1.81, χ(1)=.08; cannabis: HRs=2.04 versus 1.33, χ(1)=16.02, p<.,001 and HRs=2.04 versus 2.73, χ(1)=2.0, p=.16). For sexual debut, parental separation was associated with greater hazard than was having one or two AUD-affected parents (HRs=2.34 versus 1.19, χ(1)=44.6, p<.0001 and versus 1.43, χ(1)=19.3, p<.0001).

DISCUSSION

Subjects with two AUD-affected parents were at greater risk for early initiation of alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use and sexual debut than were subjects with no parental AUD. Parental separation was also a consistent predictor of early substance use and sexual debut, with an effect on substance initiation equal to that of having 2 AUD-affected parents, and more strongly associated with early sexual debut than AUD in one or both parents.

Our work builds on previous work by documenting that parental AUD is a common risk factor for initiation of multiple substances and early sexual debut. Previous work has focused largely on the association between parental AUD and offspring risk for alcohol initiation and alcohol-related outcomes, with some recent attention to the association of parental AUD with offspring use of other substances (29, 30). Data from the National Epidemiological Study on Alcoholism and Related Conditions (NESARC) showed that subjects who began drinking before age 15 and from ages 15–17 reported more substance use problems in their parents than did subjects who began drinking at age 18 years and older (6). There is also evidence from twin and offspring-of-twin studies showing associations of parental alcohol problems with earlier age at alcohol use in offspring (22, 23, 56). Just one of these studies used diagnostic measures of parental AUD (23); the rest employed respondent reports of parent drinking behavior (6, 22, 56). The present study replicates and extends previous findings in its use of diagnostic measures by self-report in most parents or with family history measures of AUD.

There is less evidence of a link between parental AUD and early cigarette and cannabis use and sexual debut than for early alcohol use. Sartor and colleagues (30) found that maternal alcohol problems were associated with early age at first cigarette in a sample of offspring of twins. In an extension of that same offspring-of-twins study, Scherrer and colleagues (57) found a significant association of maternal alcohol problems with elevated odds of offspring nicotine dependence. Regarding cannabis use, parental alcohol problems were independently associated with opportunity to use cannabis in Australian twins but not with the transition to cannabis dependence (29). The present study broadens the literature on the influence of parental AUD beyond offspring alcohol use to other substances and behaviors that are often correlated with alcohol use.

The finding that AUDs in both parents had a stronger association with earlier than later cannabis use is consistent with a recent study which showed that parental alcohol problems were associated with increased opportunity to use cannabis and with increased risk of initiating use, given the opportunity (29). Recent evidence showed that the age at initiation of cannabis use was more strongly influenced by shared environment than were ages at initiation of tobacco and alcohol, suggesting that this might be due to the illegality of cannabis (in most states), making it harder to procure (14). Parents with AUDs may provide less monitoring of child behavior than parents without AUDs (18, 19), increasing the likelihood that offspring will have access to cannabis via deviant peers. Parental AUDs may also represent a general risk for psychosocial and substance use problems via increased genetic risk for conduct problems and other substance use (58).

Parental separation was a stronger predictor of sexual debut than was parental AUD, consistent with evidence that parental separation outweighs the effect of parental AUD on early use of alcohol in offspring of male twins (23), Australian twins (20) and European-American female twins (22). In an ethnically diverse sample of 12–17-year-old adolescents, age at sexual debut was significantly younger among subjects who did not live with both biological parents than among those who did (59), and 15 to 18-year old African American girls from high-poverty neighborhoods who lived with both parents were less likely than those living with single mothers to have had their sexual debut (60); neither of these studies included a measure of parental AUD. Our result showing that parental separation has a stronger effect on sexual debut than parental AUD is striking, since parental AUD is associated with increased risk for childhood adversities which themselves are associated with earlier sexual debut (61). Separated parents, like parents with AUDs, may provide less monitoring of their children, so that opportunities for substance use and risky sex are more plentiful. Parental separation may be a marker indexing a broad risk that includes lax parental monitoring as well as potentially greater genetic liability to substance use, since parents with AUD are more likely than parents without to separate (15, 16), and parental AUD is associated with increased genetic risk for other substance use in offspring (58).

Limitations and future directions

Results from this sample selected for high familial risk for AUDs might not be generalizable to population-based samples. However, the outcomes examined are normative behaviors in population-based data; it is only the timing of these behaviors that may differentiate this from population-based samples. Furthermore, more than 40% of children in the US live in homes with a parent or other adult with alcohol problems (62), and these data may be used to infer risks associated with parental AUD for any child. Parental use of substances other than alcohol was not included, and the timing of parental AUDs or parental separation was not modeled in relation to offspring outcomes. It is possible that remitted parental AUDs might have a different association with outcomes (e.g., null or even protective), or that timing of parental separation is differentially associated with risk. Despite these limitations, the high prevalence of parental AUDs in this sample provides the opportunity to examine parental effects on timing of first use. Future work examining the progression of offspring substance involvement including AUDs in relation to the course of parental AUDs will be important.

Conclusions

Parental AUDs and parental separation are independent and consistent predictors of increased risk for early alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use and sexual debut in offspring, after accounting for other risks associated with early substance use and sexual debut.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA), Principal Investigators B. Porjesz, V. Hesselbrock, H. Edenberg, L. Bierut, includes eleven different centers: University of Connecticut (V. Hesselbrock); Indiana University (H.J. Edenberg, J. Nurnberger Jr., T. Foroud); University of Iowa (S. Kuperman, J. Kramer); SUNY Downstate (B. Porjesz); Washington University in St. Louis (L. Bierut, J. Rice, K. Bucholz, A. Agrawal); University of California at San Diego (M. Schuckit); Rutgers University (J. Tischfield, A. Brooks); Department of Biomedical and Health Informatics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Department of Genetics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA (L. Almasy), Virginia Commonwealth University (D. Dick), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (A. Goate), and Howard University (R. Taylor). Other COGA collaborators include: L. Bauer (University of Connecticut); J. McClintick, L. Wetherill, X. Xuei, Y. Liu, D. Lai, S. O’Connor, M. Plawecki, S. Lourens (Indiana University); G. Chan (University of Iowa; University of Connecticut); J. Meyers, D. Chorlian, C. Kamarajan, A. Pandey, J. Zhang (SUNY Downstate); J.-C. Wang, M. Kapoor, S. Bertelsen (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai); A. Anokhin, V. McCutcheon, S. Saccone (Washington University); J. Salvatore, F. Aliev, B. Cho (Virginia Commonwealth University); and Mark Kos (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley). A. Parsian and M. Reilly are the NIAAA Staff Collaborators.

We continue to be inspired by our memories of Henri Begleiter and Theodore Reich, founding PI and Co-PI of COGA, and also owe a debt of gratitude to other past organizers of COGA, including Ting-Kai Li, P. Michael Conneally, Raymond Crowe, and Wendy Reich, for their critical contributions. This national collaborative study is supported by NIH Grant U10AA008401 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Declaration: None

References

- 1.Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King KM, Chassin L. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:256–265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Martin NG, Heath AC. Timing of first alcohol use and alcohol dependence: evidence of common genetic influences. Addiction. 2009;104:1512–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Patricia Chou S, June Ruan W, Grant BF. Age at First Drink and the First Incidence of Adult-Onset DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Duncan AE, Haber JR, et al. Associations of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and drug use/dependence with educational attainment: evidence from cotwin-control analyses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1412–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King KM, Meehan BT, Trim RS, Chassin L. Marker or mediator? The effects of adolescent substance use on young adult educational attainment. Addiction. 2006;101:1730–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal A, Few L, Nelson EC, Deutsch A, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, et al. Adolescent cannabis use and repeated voluntary unprotected sex in women. Addiction. 2016 doi: 10.1111/add.13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bierman KL, Coie JD, Dodge KA, Greenberg M, Lochman JE, McMahon RJ, et al. Trajectories of Risk for Early Sexual Activity and Early Substance Use in the Fast Track Prevention Program. Prevention Science. 2014;15:S33–S46. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0328-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hipwell A, Stepp S, Chung T, Durand V, Keenan K. Growth in Alcohol Use as a Developmental Predictor of Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Risk-Taking. Prevention Science. 2012;13:118–128. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0260-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler T, Lifford K, Shelton K, Rice F, Thapar A, Neale MC, et al. Exploring the relationship between genetic and environmental influences on initiation and progression of substance use. Addiction. 2007;102:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han C, McGue MK, Iacono WG. Lifetime tobacco, alcohol and other substance use in adolescent Minnesota twins: univariate and multivariate behavioral genetic analyses. Addiction. 1999;94:981–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richmond-Rakerd LS, Slutske WS, Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, et al. Age at First Use and Later Substance Use Disorder: Shared Genetic and Environmental Pathways for Nicotine, Alcohol, and Cannabis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016 doi: 10.1037/abn0000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donovan JE, Molina BS. Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:741–751. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1355–1364. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents’ and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldron M, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, Lynskey MT, Slutske WS, Glowinski AL, et al. Parental separation and early substance involvement: results from children of alcoholic and cannabis dependent twins. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldron M, Doran KA, Bucholz KK, Duncan AE, Lynskey MT, Madden PA, et al. Parental separation, parental alcoholism, and timing of first sexual intercourse. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waldron M, Vaughan EL, Bucholz KK, Lynskey MT, Sartor CE, Duncan AE, et al. Risks for early substance involvement associated with parental alcoholism and parental separation in an adolescent female cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant JD, Waldron M, Sartor CE, Scherrer JF, Duncan AE, McCutcheon Vivia V, et al. Parental Separation and Offspring Alcohol Involvement: Findings from Offspring of Alcoholic and Drug Dependent Twin Fathers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:1166–1173. doi: 10.1111/acer.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capaldi DM, Tiberio SS, Kerr DCR, Pears KC. The Relationships of Parental Alcohol Versus Tobacco and Marijuana Use With Early Adolescent Onset of Alcohol Use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:95–103. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. Alcohol use from ages 9 to 16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong JM, Ruttle PL, Burk LR, Costanzo PR, Strauman TJ, Essex MJ. Early risk factors for alcohol use across high school and its covariation with deviant friends. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:746–756. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussong A, Bauer D, Chassin L. Telescoped trajectories from alcohol initiation to disorder in children of alcoholic parents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:63–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hines LA, Morley KI, Strang J, Agrawal A, Nelson EC, Statham D, et al. Onset of opportunity to use cannabis and progression from opportunity to dependence: Are influences consistent across transitions? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartor CE, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Duncan AE, Haber JR, et al. Psychiatric and familial predictors of transition times between smoking stages: results from an offspring-of-twins study. Addict Behav. 2008;33:235–251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JIJ, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hesselbrock M, Easton C, Bucholz KK, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V. A validity study of the SSAGA--a comparison with the SCAN. Addiction. 1999;94:1361–1370. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reich T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Williams JT, Rice JP, Van Eerdewegh P, et al. Genome-wide search for genes affecting the risk for alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurnberger JI, Jr, Wiegand R, Bucholz K, O’Connor S, Meyer ET, Reich T, et al. A family study of alcohol dependence: coaggregation of multiple disorders in relatives of alcohol-dependent probands. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1246–1256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Agrawal A, Dick DM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer JR, et al. Comparison of Parent, Peer, Psychiatric, and Cannabis Use Influences Across Stages of Offspring Alcohol Involvement: Evidence from the COGA Prospective Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:359–368. doi: 10.1111/acer.13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuperman S, Chan G, Kramer JR, Bierut L, Bucholz KK, Fox L, et al. Relationship of age of first drink to child behavioral problems and family psychopathology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1869–1876. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183190.32692.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice JP, Reich T, Bucholz KK, Neuman RJ, Fishman R, Rochberg N, et al. Comparison of Direct Interview and Family History Diagnoses of Alcohol Dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zywiak WH, O’Malley SS. Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: the COMBINE Study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:837–846. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:135–174. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skinner SR, Robinson M, Smith MA, Robbins SC, Mattes E, Cannon J, et al. Childhood behavior problems and age at first sexual intercourse: a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2015;135:255–263. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:106–119. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill SY, Tessner KD, McDermott MD. Psychopathology in offspring from families of alcohol dependent female probands: A prospective study. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breslau N, Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Lucia VC, Anthony JC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: a study of youths in urban America. J Urban Health. 2004;81:530–544. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werner KB, McCutcheon VV, Agrawal A, Sartor CE, Nelson EC, Heath AC, et al. The association of specific traumatic experiences with cannabis initiation and transition to problem use: Differences between African-American and European-American women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Werner KB, Sartor CE, McCutcheon VV, Grant JD, Nelson EC, Heath AC, et al. Association of Specific Traumatic Experiences With Alcohol Initiation and Transitions to Problem Use in European American and African American Women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:2401–2408. doi: 10.1111/acer.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Nelson EC, Waldron M, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and the course of alcohol dependence development: Findings from a female twin sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:327–343. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Wiley series in probability and statistics. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. Applied survivial analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allison PD. Survival analysis. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences. New York: Routledge; 2010. pp. 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 55.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The Role of Childhood Risk Factors in Initiation of Alcohol Use and Progression to Alcohol Dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scherrer JF, Xian H, Pan H, Pergadia ML, Madden PA, Grant JD, et al. Parent, sibling and peer influences on smoking initiation, regular smoking and nicotine dependence. Results from a genetically informative design. Addict Behav. 2012;37:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hicks BM, Foster KT, Iacono WG, McGue M. Genetic and Environmental Influences on the Familial Transmission of Externalizing Disorders in Adoptive and Twin Offspring. Jama Psychiatry. 2013;70:1076–1083. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Upchurch DM, Levy-Storms L, Sucoff CA, Aneshensel CS. Gender and Ethnic Differences in the Timing Of First Sexual Intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore MR, Chase-Lansdale PL. Sexual Intercourse and Pregnancy Among African American Girls in High-Poverty Neighborhoods: The Role of Family and Perceived Community Environment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1146–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grant BF. Estimates of US children exposed to alcohol abuse and dependence in the family. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:112–115. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.