Physical inactivity is estimated to cause as many deaths globally each year as does smoking1. Current guidelines recommend ≥150 minutes/week of moderate intensity aerobic physical activity (PA) and muscle-strengthening exercises on ≥2 days/week.2 These guidelines are based primarily on studies using self-reported moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA (MVPA).2 Technological developments now enable device assessments of light-intensity physical activity (LPA) and sedentary behavior, and well-designed studies with such assessments that investigate clinical outcomes are needed for updating current guidelines. Here, we present data from the Women’s Health Study (WHS). (The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.)

From 2011–2015, 18,289 of 29,494 living women agreed to participate; 1,456 were ineligible because they could not walk unassisted outside the home. Women provided written consent to participate, and the study was approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s institutional review board committee. Participants were younger and healthier than non-participants. Women were mailed a triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph GT3X+, ActiGraph Corp), asked to wear this on the hip for seven days (except during sleep and water-based activities) and then mail back the device. 17,708 women wore their devices. Of 17,466 devices recording data (242 devices failed), 16,741 (96%) had data from ≥10 hours/day on ≥4 days (convention for compliant wear). Women were followed through 12/31/2015 for mortality, with deaths confirmed using medical records, death certificates or the National Death Index.

We examined the associations of total volume of PA (total accelerometer counts/day), MVPA (minutes/day), LPA (minutes/day) and sedentary behavior (minutes/day) with mortality using proportional hazards regression. MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior were categorized using triaxial accelerometer cutpoints [MVPA (accelerometer vector magnitude ≥2690 counts per minute, cpm), LPA (200-2689 cpm), and sedentary behavior (<200 cpm)]. 3 Initial models were adjusted for age and accelerometer wear time; a second model was additionally adjusted for potential confounders (see Figure). Analyses of LPA and sedentary behavior were also adjusted for MVPA as these behaviors were correlated (MVPA and LPA minutes/day, r = 0.36; MVPA and sedentary minutes/day, r= −0.44).

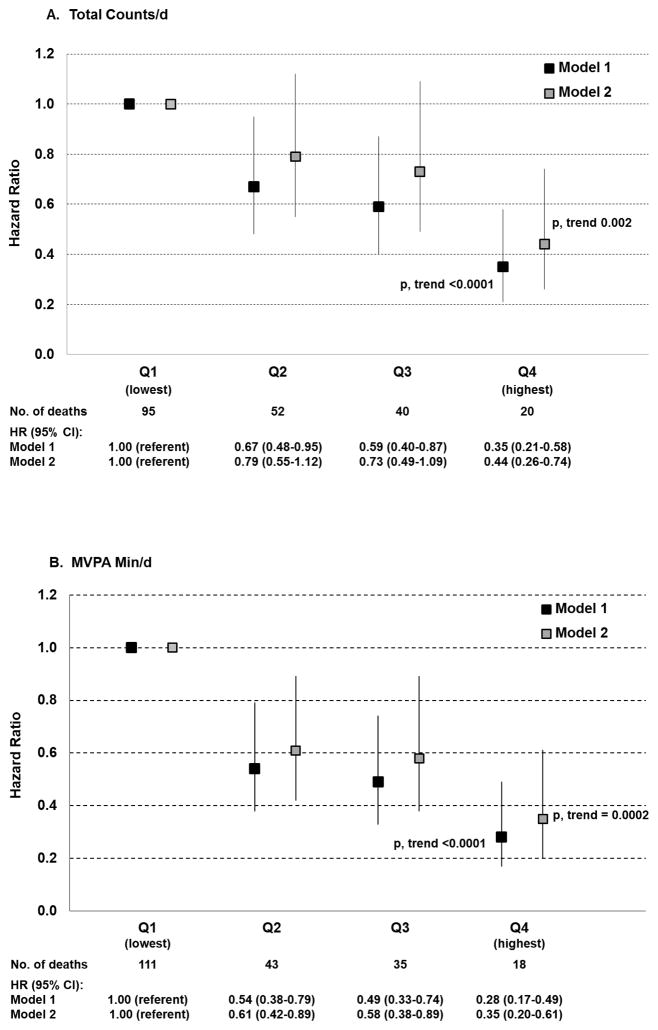

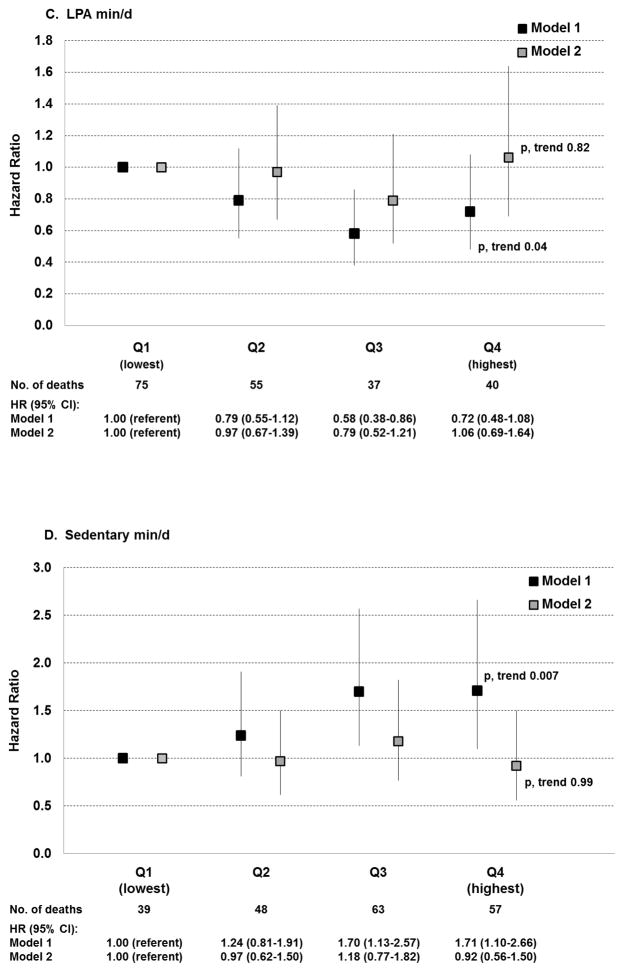

Figure. Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for All-Cause Mortality by Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior.

Hazard ratios are for quartiles of triaxial accelerometer-assessed: A. total counts/d (measure of total PA); B. moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) min/d; C. light-intensity physical activity (LPA) min/d; D. sedentary min/d.

Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Model 1 is adjusted for age and wear time. Model 2 is additionally adjusted for smoking; alcohol; intakes of saturated fat, fiber, fruits and vegetables; hormone therapy; parental history of myocardial infarction; family history of cancer; general health; history of cardiovascular disease; history of cancer; cancer screening. Analyses of MVPA and LPA are mutually adjusted; analyses of sedentary behavior also are adjusted for MVPA.

At baseline, the mean age was 72.0 (standard deviation, 5.7) years and mean wear time, 14.9 (1.3) hours/day. The median times of MVPA, LPA, and sedentary behavior were 28, 351, and 503 minutes/day, respectively. During an average follow-up of 2.3 years, 207 women died. Total volume of PA was inversely related to mortality after adjusting for potential confounders; p, trend = 0.002 (Figure). For MVPA, there also was a strong and inverse association; p, trend = 0.0002. This association persisted in sensitivity analyses that excluded: (1) women with CVD and cancer and those rating their health as fair/poor; or (2) deaths in the first year (data not shown).

For LPA, in age and wear time adjusted analysis, there was a significant inverse association; p, trend = 0.04. With adjustment for potential confounders and MVPA, this association was no longer apparent; p, trend = 0.82. Parallel (but directionally opposite) findings were seen with sedentary behavior (p, trend = 0.0007 and 0.99, respectively).

In this large study of women with triaxial accelerometer-assessed PA, three main findings emerged. First, we observed a strong, inverse association between overall volume of PA and all-cause mortality. While this inverse relation is not novel, the magnitude of risk reduction (~60–70%, comparing extreme quartiles) was far larger than that estimated from meta-analyses of studies using self-reported PA (~20–30%). Second, the strong, inverse association for overall volume of activity was primarily attributable to the strong, inverse association between MVPA and mortality. Third, we did not find any associations of LPA or sedentary behavior with mortality after accounting for MVPA.

This study is one of the first investigations of PA and a clinical outcome utilizing newer generation accelerometers capable of measuring activity along three planes. Using triaxial instead of uniaxial data increases the sensitivity for recognizing PA, detecting more time in LPA and less time in sedentary behavior.

A few previous studies of device-assessed PA, mainly using uniaxial devices, and mortality have yielded inconsistent findings.4 Additionally, a large number of studies have examined device-assessed sedentary behavior in relation to biomarkers. However, the vast majority are cross-sectional studies, limiting the interpretation of findings.5

The present study adds meaningfully to existing data due to its large sample size, use of triaxial accelerometer data, and investigation of a clinical outcome. Although the short-term follow-up could raise the possibility of reverse causation as an explanation for the findings, we observed a consistent pattern of results after excluding early deaths within one year of PA ascertainment. While we did adjust for potential confounders, these were self-reported (apart from CVD and cancer diagnoses, confirmed with medical records) and may have led to overestimates for MVPA. Finally, the overall participation rate among eligible women was 63%; while comparing favorably with other studies that have used devices to measure PA (e.g., 44% in the UK Biobank study), it may limit the generalizability of findings.

This study provides support for the 2008 federal guideline recommendation of MVPA,2 but it does not support either increasing LPA or decreasing sedentary behavior for mortality risk reduction. As physical activity guidelines are updated,2 additional data on other clinical outcomes are needed to fully inform any revisions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants and staff of the Women’s Health Study, particularly Bonnie Church, MS and Colby Smith, BS for accelerometer data collection, and to Eunjung Kim, MS for conducting data analyses.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA154647, CA047988, CA182913, HL043851, HL080467 and HL099355. Dr. Shiroma is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kamada is supported by a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad and Young Scientists. The sponsor had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Physical Activity Guidelines. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed 8/14/17]. URL: www.health.gov/paguidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evenson KR, Wen F, Herring AH. Associations of accelerometry-assessed and self-reported physical activity and sedentary behavior with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:621–632. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirth K, Klenk J, Brefka S, Dallmeier D, Faehling K, Figuls MR, Tully MA, Gine-Garriga M, Caserotti P, Salva A, Rothenbacher D, Denkinger M, Stubbs B on behalf of the SITLESS consortium. Biomarkers associated with sedentary behaviour in older adults: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:87–111. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]