Abstract

Background

With the aging of the population and rising incidence of thromboembolic events, the usage of antiplatelet agents is also increasing. There are few reports yet on the management of antiplatelet agents for patients undergoing colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

Aims

The aim of this study is to evaluate whether continued administration of antiplatelet agents is associated with an increased rate of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD.

Methods

A total of 1022 colorectal neoplasms in 927 patients were dissected at Yokohama City University Hospital and its three affiliate hospitals between July 2012 and June 2017. We included the data of 919 lesions in the final analysis. The lesions were divided into three groups: the no-antiplatelet group (783 neoplasms), the withdrawal group (110 neoplasms), and the continuation group (26 neoplasms).

Results

Among the 919 lesions, bleeding events occurred in a total of 31 (3.37%). The rate of bleeding after ESD was 3.3% (26/783), 4.5% (5/110), and 0% (0/26), respectively. There were no significant differences in the rate of bleeding after ESD among the three groups (the withdrawal group vs. the no-antiplatelet group, the continuation group vs. the no-antiplatelet group, and the withdrawal group vs. the continuation group).

Conclusions

Continued administration of antiplatelet agents is not associated with any increase in the risk of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD. Prospective, randomized studies are necessary to determine whether treatment with antiplatelet agents must be interrupted prior to colorectal ESD in patients who are at a high risk of thromboembolic events.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10620-017-4843-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasm, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Antiplatelet agent, Bleeding after ESD

Introduction

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) continues to increase worldwide [1, 2], and the importance of early detection and early treatment is growing. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has spread rapidly as an effective treatment strategy for early-stage CRC. ESD is an excellent treatment modality for superficial colorectal neoplasms, because it allows en bloc resection, regardless of the lesion size [3–6]. However, despite its efficacy, there is major concern about bleeding as a complication of this procedure.

Antiplatelet agents are prescribed to prevent cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases [7, 8]. Usage of antiplatelet agents has increased with the aging of the population and rising incidence of thromboembolic events. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), and the British Society for Gastroenterology have all published guidelines for the management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures [9–11]. The ESGE guideline recommends discontinuation of any antiplatelet agents, including aspirin, prior to ESD, provided that the patient is not a high-risk candidate for thromboembolic events [10]. In Japan, the 2012 Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guideline recommends perioperative continuation of low-dose aspirin (LDA) and cilostazol for patients who are at a high risk of thromboembolic events. However, it is very difficult to estimate the actual risk of thromboembolic events in any given patient. In addition, the evidence for this strategy of withdrawing antiplatelet agents prior to ESD is scarce, because of insufficient evaluation of the validity of this strategy, particularly, for colorectal ESD. While a number of reports have been published on the management of antiplatelet agents for gastric ESD [12–16], reports on the management of antiplatelet agents for colorectal ESD are scarce, and with no large-scale trials having been conducted, the available evidence is weak [17, 18]. Thus, the optimal strategy for antiplatelet agent therapy in patients undergoing colorectal ESD has not been clarified yet. In this study, we attempted to evaluate whether continued administration of antiplatelet agents is associated with an increased rate of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD, and to gather evidence for appropriate management of antiplatelet agents for colorectal ESD.

Methods

Patients

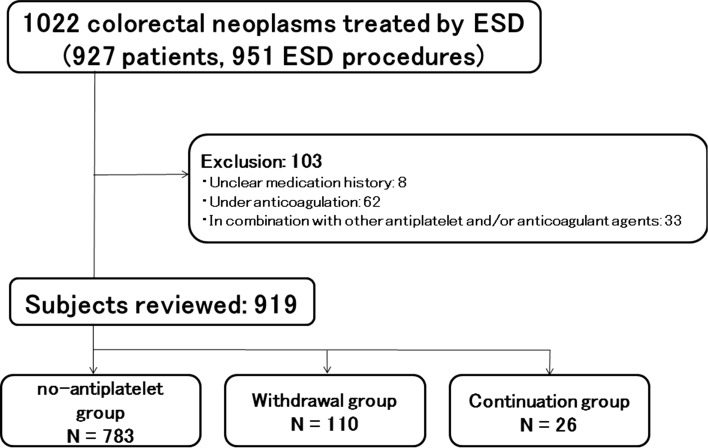

ESD was carried out for a total of 1022 neoplasms in 927 patients at Yokohama City University Hospital and its three affiliate hospitals between July 2012 and June 2017. The indications for ESD at our hospitals are identical to those reported previously [19, 20], as follows: (a) large lesions (> 20 mm in diameter) for which endoscopic treatment is indicated, but which are difficult to resect en bloc by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR); (b) mucosal lesions with fibrosis caused by prolapse due to biopsy or peristalsis of the lesions; (c) local residual early cancer detected after endoscopic resection; and (d) sporadic localized tumors in a background of chronic inflammatory disease, such as ulcerative colitis. Before ESD, we examined all the lesions primarily by magnifying endoscopy and determined the indications for ESD. We excluded patients who were taking any anticoagulant agents and/or other antithrombotic drugs (Fig. 1). We only included patients who were taking not more than a single antiplatelet agent in this study.

Fig. 1.

The study flow. Finally, a total of 919 lesions in 843 patients were included in the analysis

The histopathological diagnoses were made in accordance with the WHO classification system [21]. The depth of submucosal invasion was determined according to the General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Studies on Cancer of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus published by the Japanese Society for the Colon and Rectum [22], and the lesion type was classified as serrated lesion, adenoma (including tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma), intramucosal adenocarcinoma (M), submucosal minutely invasive adenocarcinoma (SM invasion depth < 1000 µm), or submucosal deeply invasive adenocarcinoma (SM invasion depth ≥ 1000 µm). Antiplatelet agents were defined as drugs that decrease platelet aggregation or inhibit thrombus formation, such as cyclooxygenase inhibitors, e.g., aspirin, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, e.g., cilostazol, adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibitors, e.g., clopidogrel or ticlopidine, arachidonic acid metabolism inhibitors, e.g., eicosapentaenoic acid, and prostaglandin E1 derivatives, e.g., limaprost alfadex.

In this study, we termed each lesion resected by ESD as a “subject”; two or three lesions resected by the same ESD procedure were counted as two or three subjects. The study protocol was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethics Guidelines for Clinical Research published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Yokohama City University Hospital on March 6, 2017. The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by the institutional ethics committees at each of the participating institutions.

ESD Procedure

Bowel preparation for the procedure was initiated a day prior to the ESD. Each patient was instructed to consume a low-residue diet and take 5 mg of oral sodium picosulfate on the evening before the ESD. On the day of the ESD, each patient was given 2000 ml of polyethylene glycol (PEG). If the stools were not sufficiently clear, an additional 1000–2000 ml of PEG was given to ensure sufficient bowel cleaning.

All procedures were performed with a standard colonoscope with a water-jet function (EVIS CF-Q260DI, PCF-260JI; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A transparent hood was attached to the tip of the endoscope in all cases. Carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation was used instead of room air insufflation. Pentazocine (15 mg) was administered routinely at the start of the ESD, and midazolam for sedation, as needed, during the procedure. Cardiorespiratory functions were monitored during the ESD. As the injection solution, we used a mixture of 0.4% sodium hyaluronate (Muco UpR; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and indigo carmine with diluted epinephrine. The VIO300D system (ERBE Elektromedizin, Tuebingen, Germany) was used as the power source for the electrical cutting and coagulation, and the tissue dissection was performed with a dual knife (Olympus). Mucosal incision was made using the endo-cut current (effect 2, 30 W), and endoscopic hemostasis was achieved with a dual knife in coagulation mode. When hemostasis could not be achieved with the dual knife alone, we used hemostatic forceps. We started the patients on a fluid diet from post-ESD day (POD) 2 and carefully followed the patients’ symptoms. The discharge criteria were absence of blood in the stool and absence of abdominal pain after resumption of oral intake of meals. In the absence of any problems, the patients were discharged on POD 4.

The patients were instructed to call the hospital in case of overt bleeding after discharge and visit the emergency department immediately. Two weeks after discharge, each patient visited the outpatient department to obtain confirmation of the final pathological results and for clinical assessment of delayed bleeding.

Data Analysis and Definition of Bleeding After ESD

All subjects were divided into three groups: no-antiplatelet group, withdrawal group, and continuation group. Patients who had never used any antiplatelet agents or had discontinued such drugs ≥ 30 days prior to the ESD were classified into the no-antiplatelet group. Patients who had antiplatelet agent interrupted ≥ 7 days before ESD were classified into the withdrawal group. Patients in whom the antiplatelet agent administration was continued, or had been interrupted < 7 days before the ESD were classified into the continuation group. Whether to withdraw or continue was judged by the physician who prescribed antiplatelet agents with estimating the risk of thromboembolic events in each patient. Bleeding after ESD was defined as a fall in the hemoglobin level by at least 2 g/dl below the most recent preoperative level, or necessitation of endoscopic hemostasis and/or blood transfusion, and/or massive melena [23].

To investigate the potential risk factors for bleeding after ESD, we investigated the age, sex, and comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, or hematologic disease) as factors that may potentially affect the risk of bleeding or coagulation, tumor location, diameter of the resected specimen (< 30 mm/≥ 30 mm), control of bleeding during ESD (good or poor), ESD procedure time, pathological diagnosis, complete en bloc resection rate, status of antiplatelet agent therapy (no-antiplatelet, withdrawal, or continuation), and the frequency of bleeding after ESD. Poor control of bleeding during ESD was defined as active bleeding that necessitated the use of hemostatic forceps because use of the dual knife alone was ineffective to achieve hemostasis. ESD procedure time was defined as duration from starting of the injection until end of dissection. Complete en bloc resection was defined as resection of the lesion with a pathological negative margin. We used the cutoff specimen diameter of 30 mm for candidate, based on a previous report that showed that a specimen diameter of more than 30 mm was a risk factor for bleeding after colorectal ESD [24].

Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as means or medians (± standard deviation or range) for the quantitative data and as frequencies (percentage) for the categorical data. Categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Data showing normal distribution were compared by the t test, and those showing non-normal distribution were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test, to assess the statistical significance of differences. p < 0.05 was considered as denoting statistical significance. Multivariate analyses were performed using the risk factors that were identified as being significant by univariate analyses plus history of use of antiplatelet agents. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistics, version 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study Flow

We performed colorectal ESD in 927 patients (951 ESD procedures, 1022 colorectal neoplasms) at Yokohama City University Hospital and its three affiliate hospitals between July 2012 and June 2017. We excluded 103 neoplasms from the analysis, with the final analysis performed on the remaining 919 neoplasms (843 patients, 862 ESD procedures; Fig. 1). The major reason for exclusion was under anticoagulation (n = 62). Depending on the protocol for antiplatelet agent administration, the subjects were divided into three groups: the no-antiplatelet group (783 neoplasms), the withdrawal group (110 neoplasms), and the continuation group (26 neoplasms).

Patient Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The total number of patients was 843, and the mean ages ± SD of the patients in the no-antiplatelet group, withdrawal group, continuation group were 68.4 ± 10.4, 69.5 ± 7.1, and 68.6 ± 7.1 years respectively. The antiplatelet agents were used for ischemic heart disease in 29% of patients of the withdrawal group and 50% of patients of the continuation group; they were used for cerebrovascular disease in 28% of patients of the withdrawal group and 30% of patients of the continuation group; they were used as preventive medication in 38% of patients of the withdrawal group and 5% of patients of the continuation group. Thus, more patients received the drug as preventive medication in the withdrawal group than in the continuation group. The number of the days from ESD to resumption of antiplatelet agent intake was 2.55 ± 1.7 in the withdrawal group and 0.13 ± 0.4 in the continuation group. The continuation group included only two patients who did not take antiplatelet agents on the day of the ESD, while the remaining 24 of 26 patients continued taking their routine antiplatelet agents through the morning of the ESD. The types of antiplatelet agents used are presented in Table 2. Antiplatelet agents were used in a total of 117 patients, with aspirin being the predominantly used drug (62.4%), followed by clopidogrel (17.9%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with colorectal tumors resected by ESD in the total sample and per group

| Characteristics of the patients | No-antiplatelet group | Withdrawal group | Continuation group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (total = 843) | 726 | 97 | 20 |

| Sex (M:F) | 410:316 | 70:27 | 12:8 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 68.4 ± 10.4 | 69.5 ± 7.1 | 68.6 ± 7.1 |

| Number of days to resumption of antiplatelet agent intake | – | 2.55 ± 1.7 | 0.13 ± 0.4 |

| Reason for use of antiplatelet agents | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | – | 28 (29%) | 10 (50%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | – | 27 (28%) | 6 (30%) |

| Carotid stenosis | – | 2 (2%) | 2 (10%) |

| As preventive medication | – | 37 (38%) | 1 (5%) |

| Other | – | 3 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection

Table 2.

Type of antiplatelet agents (the number of patients taking antiplatelet agents was 117)

| No | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 73 | 62.4 |

| Clopidogrel | 21 | 17.9 |

| Cilostazol | 11 | 9.4 |

| Limaprost alfadex | 7 | 6 |

| Ethyl icosapentate | 3 | 2.6 |

| Ticlopidine | 2 | 1.7 |

Characteristics of the Colorectal Neoplasms

The characteristics of the colorectal neoplasms are presented in Table 3. The total number of subjects was 919, and the number of lesions resected from subjects who were prescribed antiplatelet agents was 136. In all, 223 (28%), 22 (20%), and 5 (19%) lesions from the three groups, respectively, were located in the rectum. The mean specimen diameter was 34.2 ± 14.4, 33.3 ± 17.2, and 30.6 ± 9.1 mm, respectively. The polypoid growth pattern was rare in all three groups, with no significant differences among the groups. The mean procedure time was 65.8 ± 56.2, 60.5 ± 49.7, and 56.1 ± 67.6 min, respectively. The complete en bloc resection rates in the three groups were 97.8, 94.5, and 92%, respectively. The rate of bleeding after ESD was 3.3% (26/783), 4.5% (5/110), and 0% (0/26), respectively. It is worthy of note that there were no cases of bleeding after ESD in the continuation group. There were no significant differences in the tumor location (colon vs. rectum), specimen diameter, growth pattern, procedure time, complete en bloc resection rate, rate of percentage of patients with poor control of bleeding during ESD, rate of perforation, or rate of Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm among the three groups.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of colorectal tumors resected by ESD in the total sample and per group

| Characteristics of the subjects | No-antiplatelet group | Withdrawal group | Continuation group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (total = 919) | 783 | 110 | 26 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Colon | 560 (72%) | 88 (80%) | 21 (81%) |

| Rectum | 223 (28%) | 22 (20%) | 5 (19%) |

| Specimen diameter, mm (mean ± SD) | 34.2 ± 14.4 | 33.3 ± 17.2 | 30.6 ± 9.1 |

| Growth pattern | |||

| Polypoid | 132 (17%) | 17 (15%) | 3 (12%) |

| LST-G | 354 (45%) | 48 (44%) | 13 (50%) |

| LST-NG | 297 (38%) | 45 (41%) | 10 (38%) |

| Procedure time, min (mean ± SD) | 65.8 ± 56.2 | 60.5 ± 49.7 | 56.1 ± 67.6 |

| Complete en bloc resection | |||

| Yes | 766 (97.8%) | 104 (94.5%) | 24 (92%) |

| No | 17 (2.2%) | 6 (5.5%) | 2 (8%) |

| Bleeding control during ESD | |||

| Good | 711 (90.8%) | 105 (95.5%) | 24 (92%) |

| Poor | 72 (9.2%) | 5 (4.5%) | 2 (8%) |

| Prophylactic clipping | |||

| Yes | 181 (23.1%) | 15 (13.6%) | 9 (35%) |

| No | 602 (76.9%) | 95 (86.4%) | 17 (65%) |

| Bleeding after ESD | |||

| Yes | 26 (3.3%) | 5 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| No | 757 (96.7%) | 105 (95.5%) | 26 (100%) |

| Perforation | |||

| Yes | 22 (2.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (4%) |

| No | 761 (97.2%) | 109 (99.1%) | 25 (96%) |

| Histopathology | |||

| Serrated lesion | 84 (10.7%) | 8 (7.3%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Adenoma | 331 (42.3%) | 41 (37.3%) | 12 (46%) |

| Ca-M | 276 (35.2%) | 50 (45.4%) | 8 (31%) |

| Ca-SM invasion < 1000 µm | 46 (5.9%) | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm | 46 (5.9%) | 8 (7.3%) | 2 (7.7%) |

ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection, LST-G laterally spreading tumor, granular type, LST-NG laterally spreading tumor, non-granular type, Ca-M intramucosal adenocarcinoma, Ca-SM carcinoma with submucosal invasion

P value: NS

Risk Factors for Bleeding After Colorectal ESD

The results of univariate analysis conducted to identify the risk factors for bleeding after colorectal ESD are presented in Table 4. A total of 31 bleeding events occurred (3.37%) in the 919 subjects. Of the 31 cases of bleeding after ESD, the lesion was located in the rectum in 19 cases (p < 0.001), and the lesion was ≥ 30 mm in diameter in 21 cases (p = 0.046). Among the lesions for which the ESD procedure time was ≥ 65 min, bleeding after ESD occurred in 20 (p = 0.002), and among the lesions in which the histopathology revealed Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm, bleeding after ESD occurred in eight cases (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in any of the other variables (growth pattern, complete en bloc resection rate, ease of bleeding control during ESD, rate of performance of prophylactic clipping, perforation rate, antiplatelet agents used) between the group with bleeding after ESD and the group without bleeding after ESD. With regard to the antiplatelet agents used, there were no significant differences among the three groups (withdrawal group vs. no-antiplatelet group, continuation group vs. no-antiplatelet group, and withdrawal group vs. continuation group).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis to identify risk factors for bleeding after colorectal ESD

| Characteristics of the subjects | Bleeding after ESD | No bleeding after ESD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (total = 919) | 31 | 888 | |

| Tumor location | < 0.001 | ||

| Rectum | 19 (61.3%) | 231 (26%) | |

| Colon | 12 (38.7%) | 657 (74%) | |

| Specimen diameter (mm) | 0.046 | ||

| ≥ 30 mm | 21 (67.7%) | 437 (49.3%) | |

| < 30 mm | 10 (32.3%) | 451 (50.8%) | |

| Growth pattern | NS | ||

| Polypoid | 9 (29%) | 143 (16.1%) | |

| LST | 22 (71%) | 745 (83.9%) | |

| Procedure time | 0.002 | ||

| ≥ 65 min | 20 (64.5%) | 315 (35.5%) | |

| < 65 min | 11 (35.5%) | 573 (64.5%) | |

| Complete en bloc resection | NS | ||

| Yes | 29 (93.5%) | 865 (97.4%) | |

| No | 2 (6.5%) | 23 (2.6%) | |

| Bleeding control during ESD | NS | ||

| Good | 26 (83.9%) | 814 (91.7%) | |

| Poor | 5 (16.1%) | 74 (8.3%) | |

| Prophylactic clipping | NS | ||

| Yes | 6 (19.4%) | 199 (22.4%) | |

| No | 25 (80.6%) | 689 (77.6%) | |

| Perforation | NS | ||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 24 (2.7%) | |

| No | 31 (100%) | 864 (97.3%) | |

| Histopathology | < 0.001 | ||

| Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm | 8 (25.8%) | 48 (5.4%) | |

| Others | 23 (74.2%) | 840 (94.6%) | |

| Antiplatelet agents (vs. withdrawal) | NS | ||

| Withdrawal group | 5 (16.1%) | 105 (12.2%) | |

| No-antiplatelet group | 26 (83.9%) | 757 (87.8%) | |

| Antiplatelet agents (vs. continuation) | NS | ||

| Continuation group | 0 (0%) | 26 (3.3%) | |

| No-antiplatelet group | 26 (100%) | 757 (96.7%) | |

| Antiplatelet agents (users only) | NS | ||

| Continuation group | 0 (0%) | 26 (19.8%) | |

| Withdrawal group | 5 (100%) | 105 (80.2%) |

ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection, LST laterally spreading tumor, Ca-M intramucosal adenocarcinoma; Ca-SM carcinoma with submucosal invasion, NS not significant

We performed multivariate analysis using the risk factors that were identified as being significant by the univariate analyses plus history of use of antiplatelet agents. Table 5 shows the risk factors that were identified by multivariate analysis as being significantly and independently associated with bleeding after ESD, namely location of the lesion in the rectum [p < 0.001, OR (95% CI) 3.98 (1.866–8.494)], ESD procedure time ≥ 65 min [p = 0.018, OR (95% CI) 2.56 (1.176–5.572)], and Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm [p = 0.027, OR (95% CI) 2.88 (1.130–7.355)]. Multivariate analysis also revealed no significant influence of antiplatelet agent use (no-antiplatelet group vs. withdrawal group or continuation group).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis to identify risk factors for bleeding after colorectal ESD

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rectum | 3.98 | 1.866–8.494 | < 0.001 |

| Procedure time ≥ 65 min | 2.56 | 1.176–5.572 | 0.018 |

| Ca-SM invasion ≥ 1000 µm | 2.88 | 1.130–7.355 | 0.027 |

| Antiplatelet agents (vs. withdrawal or continuation) | 1.38 | 0.502–3.810 | 0.75 |

We performed backward selection for 4 variables which were identified as being statistically significant by the univariate analysis (location of the lesion in the rectum, procedure time ≥ 65 min, Ca-SM invasion depth ≥ 1000 µm, specimen diameter ≥ 30 mm); specimen diameter ≥ 30 mm was eliminated at the cutoff of p < 0.20

ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection, Ca-SM carcinoma with submucosal invasion, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

This is the first multicenter study with a large sample size conducted to investigate the optimal strategy for antiplatelet agent use in patients scheduled for colorectal ESD. Bleeding as a complication of this procedure remains a major concern. Several studies have reported the existence of an association between treatment with antiplatelet agents and the risk of bleeding in patients who have undergone polypectomy or EMR for colorectal neoplasms. However, the study results are not consistent. Boustiere et al. [10] reported that the risk of bleeding did not increase with continued use of low-dose antiplatelet agents (LDA) in 29,606 patients who underwent polypectomy. Hui et al. [25] reported that the use of antiplatelet agents during polypectomy was not associated with any increase in post-polypectomy bleeding. Manocha et al. [26] also reported that LDA use did not increase the risk of post-polypectomy bleeding. In regard to colorectal ESD, Ninomiya et al. [18] reported that in their single-center study, continued use of LDA increased the risk of bleeding after colorectal ESD as compared to that in patients who did not receive antiplatelet agents. In this previous study, although no significant difference in the bleeding rate after colorectal ESD was observed between the LDA-continuation group and LDA-interruption group, the rate was significantly higher in the LDA-continuation group as compared to that in the no-antiplatelet group. In contrast, our multicenter study showed no significant differences in the bleeding rate after colorectal ESD among the three groups (withdrawal group vs. no-antiplatelet group, continuation group vs. no-antiplatelet group, and withdrawal group vs. continuation group). There was no significant difference even between the no-antiplatelet group and the continuation group, besides that between the withdrawal group and the continuation group. In this respect, our result differed from the previous report. Our study showed that continuation of antiplatelet agents was not associated with an increased risk, even as compared to that in the no-antiplatelet group, of bleeding after colorectal ESD. This is an important finding for those in whom antiplatelet agents cannot be discontinued because of an elevated risk of thromboembolic events risks. In addition, all of the episodes of bleeding after colorectal ESD in this study could be adequately controlled by endoscopic hemostasis. Terasaki et al. [24] also reported that there were no cases of hemorrhage shock resulting from delayed bleeding and that all cases of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD were successfully treated by endoscopic hemostasis involving clipping and/or hemostatic forceps, without any need for surgical intervention. There are no reports of fatal cases or death due to bleeding after colorectal ESD. Therefore, we think that administration of antiplatelet agents should be continued, giving priority to the risk of thromboembolic events rather than the risk of bleeding.

In this study, the rate of bleeding after colorectal ESD was 3.37% (31/919). The reported rates of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD range from 0.5% to 9.5% [6, 27–30], which are not necessarily inconsistent with our results. Our study showed lesion location in the rectum, ESD procedure time ≥ 65 min, and Ca-SM invasion depth ≥ 1000 µm as independent risk factors for bleeding after colorectal ESD. In regard to the lesion location, solid stool is stored for greater periods in the rectum than in the colon; therefore, the mechanical force acting on the ulcer floor is greater in the rectum. In addition, blood vessels are more abundant in the rectum owing to the presence of the venous plexus. Therefore, it is expected that bleeding after colorectal ESD may occur more easily from an ulcer after ESD. Regarding the procedure time, the mean procedure time in the total of subject (919 lesions) was 64.9 ± 55.8 min. Therefore, we rounded off this figure and set 65 min as the cutoff value. Chiba et al. [31] reported that large lesions and presence of submucosal fibrosis increase the risk of a prolonged procedure. In such cases, with prolongation of the procedure time, a greater degree of damage of the muscularis propria may also be expected. Sorbi et al. [32] reported that vascular injury of the muscularis propria caused by coagulation is a risk factor for bleeding after polypectomy. As for the histopathology, higher cellular atypicality is considered as a risk factor for bleeding. In general, the histopathological atypicality increases with increasing size of the lesion. There is the possibility that the size of the lesion and degree of histopathological atypicality are also related to each other. Although not identified by multivariate analysis, the rate of delayed bleeding was determined by univariate analysis as being significantly higher for specimen diameter ≥ 30 mm. This may be because the area of an artificial ulcer floor after resection of larger lesions is larger and requires a relatively longer time to heal after ESD. In these cases with a high risk of bleeding, prevention of bleeding after ESD is important. There are some studies that support prophylactic clipping. Liaquat et al. [33] reported that prophylactic clipping of resection sites after endoscopic removal of large colorectal lesions reduced the risk of delayed post-polypectomy hemorrhage. Matsumoto et al. [34] also reported that prophylactic clip placement was an effective method for preventing delayed bleeding after endoscopic resection of large colorectal tumors. In contrast, Shioji et al. [35] reported that prophylactic clip application does not decrease the risk of delayed bleeding after polypectomy. However, these reports are based on polypectomy or EMR, and the results are not consistent across different studies. Therefore, whether prophylactic clip placement is effective for the prevention of delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD still remains controversial. In this study, there was no significant difference in the rate of bleeding after colorectal ESD between the cases in which prophylactic clipping was performed and those in which it was not. This may be because the resected ulcer after ESD is too large to suture using clips. There is the possibility that the coagulation of exposed vessels on the resected ulcer with hemostatic forceps is effective at preventing delayed bleeding after colorectal ESD. Therefore, we would like to perform a prospective multicenter study to identify means to prevent the bleeding after colorectal ESD in the future.

There were several limitations of this study. The first was that it was a retrospective review. However, it had the advantage of being a multicenter study with a large sample size. The second limitation was that the proportion of subjects in the continuation group was small. However, we tried to align the background factors by adding history of use of antiplatelet agents as a covariate in the multivariate analysis. With the addition of this variable, the background factors could be statistically aligned. In addition, we performed backward selection for 4 variables which were identified as being statistically significant by the univariate analysis, to overcome the problem of many variables. This analysis still identified location of the lesion in the rectum, ESD procedure time ≥ 65 min, and Ca-SM invasion depth ≥ 1000 µm as independent risk factors for bleeding after ESD. Although the small sample size was one of the limitations of this study, we consider that identification of these variables as significant risk factors for bleeding after ESD is a significant finding. Another limitation was that the types and dosages of the antiplatelet agents were not clarified. There is the possibility that the risk of bleeding differs depending on the types and dosages of the antiplatelet agents. Also, there is the possibility that patients in whom the antiplatelet agent therapy was not interrupted had a higher thromboembolic risk than the patients in the withdrawal group. This could have resulted in the lower incidence of bleeding in the continuation group. Taking into consideration these limitations, we would like to conduct a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to confirm our results.

In conclusion, continued use of antiplatelet agents in patients undergoing colorectal ESD does not increase the risk of delayed bleeding after the procedure even in comparison with the risk in the no-antiplatelet group. Prospective, randomized studies are warranted to determine whether treatment with antiplatelet agents must be interrupted or not prior to ESD for colorectal neoplasms in patients who are at a high risk of thromboembolic events.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the participating institutions for their support in recruiting eligible patients and also the patients who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- ESD

Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- ESGE

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- LDA

Low-dose aspirin

- EMR

Endoscopic mucosal resection

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- POD

Post-ESD day

- OR

Odds ratio

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

Author’s contribution

JA, TH, and AN conceived the study. JA, TH, HC, SG, KA, TN, HK, and KA performed the colorectal ESD. NM, TY, TK, KK, AF, HO, YI, and JT recruited the study participants. MT gave advice on the statistical analysis methods and interpretation of the data. Analysis and interpretation of the data were conducted by JA, TH, and MT. All the authors have read the final manuscript and have approved its submission for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10620-017-4843-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson WF, Umar A, Brawley OW. Colorectal carcinoma in black and white race. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:67–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1022264002228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamegai Y, Saito Y, Masaki N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: a safe technique for colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:418–422. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic treatment of large superficial colorectal tumors: a case series of 200 endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka S, Terasaki M, Hayashi N, et al. Warning for unprincipled colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: accurate diagnosis and reasonable treatment strategy. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:107–116. doi: 10.1111/den.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomized trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2667–2674. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, Gan SI, et al. Management of antithrombotic agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boustiere C, Veitch A, Vanbiervliet G, et al. Endoscopy and antiplatelet agents. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43:445–461. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veitch AM, Baglin TP, Gershlick AH, et al. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut. 2008;57:1322–1329. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.142497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Ito T, et al. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2913–2917. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i23.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, et al. A second-look endoscopy after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasm may be unnecessary: a retrospective analysis of postendoscopic submucosal dissection bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takizawa K, Oda I, Gotoda T, et al. Routine coagulation of visible vessels may prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection—an analysis of risk factors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:179–183. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho S-J, Choi I, Kim C, et al. Aspirin use and bleeding risk after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2012;44:114–121. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim J, Kim S, Kim J, et al. Do antiplatelets increase the risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki S, Chino A, Kishihara T, et al. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1839–1845. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ninomiya Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, et al. Risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors in patients with continued use of low-dose aspirin. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1041–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka S, Oka S, Chayama K. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: present status and future prospective, including its differentiation from endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:641–651. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka S, Oka S, Kaneko I, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: possibility of standardization. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, et al. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2010. pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tajiri H, Kitano S. Complication associated with endoscopic mucosal resection: definition of bleeding that can be viewed as accidental. Dig Endosc. 2004;16:S134–S136. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terasaki M, Tanaka S, Shigita K, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasms. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:877–882. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1901-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui AJ, Wong RM, Ching JY, et al. Risk of colonoscopic polypectomy bleeding with anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents: analysis of 1657 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:44–48. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manocha D, Singh M, Mehta N, et al. Bleeding risk after invasive procedures in aspirin/NSAID users: polypectomy study in veterans. Am J Med. 2012;12:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uraoka T, Higashi R, Kato J, et al. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection for elderly patients at least 80 years of age. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3000–3007. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1660-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurlstone DP, Atkinson R, Sanders DS, et al. Achieving R0 resection in the colorectum using endoscopic submucosal dissection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Probst A, Golger D, Anthuber M, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions of the rectosigmoid: learning curve in a European center. Endoscopy. 2012;44:660–667. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka S, Tamegai Y, Tsuda S, et al. Multicenter questionnaire survey on the current situation of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:S2–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiba H, Tachikawa J, Kurihara D, et al. Safety and efficacy of simultaneous colorectal ESD for large synchronous colorectal lesions. Endosc Int Open. 2017;05:E595–E602. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-110567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorbi D, Norton I, Conio M. Postpolypectomy lower GI bleeding: descriptive analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:690–696. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.105773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liaquat H, Rohn E, Rex DK. Prophylactic clip closure reduced the risk of delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage: experience in 277 clipped large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and 247 control lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto M, Fukunaga S, Saito Y, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic resection for large colorectal tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:1028–1034. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shioji K, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Prophylactic clip application does not decrease delayed bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:691–694. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.