Abstract

The aim of this study was to characterize hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemiology in Iran and estimate the pooled mean HCV antibody prevalence in different risk populations. We systematically reviewed and synthesized reports of HCV incidence and/or prevalence, as informed by the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, and reported our findings following the PRISMA guidelines. DerSimonian-Laird random effects meta-analyses were implemented to estimate HCV prevalence in various risk populations. We identified five HCV incidence and 472 HCV prevalence measures. Our meta-analyses estimated HCV prevalence at 0.3% among the general population, 6.2% among intermediate risk populations, 32.1% among high risk populations, and 4.6% among special clinical populations. Our meta-analyses for subpopulations estimated HCV prevalence at 52.2% among people who inject drugs (PWID), 20.0% among populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures, and 7.5% among populations with liver-related conditions. Genotype 1 was the most frequent circulating strain at 58.2%, followed by genotype 3 at 39.0%. HCV prevalence in the general population was lower than that found in other Middle East and North Africa countries and globally. However, HCV prevalence was high in PWID and populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures. Ongoing transmission appears to be driven by drug injection and specific healthcare procedures.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) related morbidity and mortality places a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide1,2. While viral hepatitis is the seventh leading cause of death globally, it is the fifth leading cause of death in the Middle East and North Arica (MENA), predominantly due to HCV3. High HCV antibody prevalence levels are found in few MENA countries4,5, mainly in Pakistan, at 4.8%6–8, and Egypt, at 14.7%9,10. Recent major breakthroughs in HCV treatment, in the form of Direct Acting Antivirals (DAA), have provided promising prospects for reducing HCV transmission and disease burden11,12. Elimination of HCV as a public health problem by 2030 has recently been set as a global target by the World Health Organization (WHO)13,14.

While HCV epidemiology in MENA countries, such as Egypt and Pakistan, has been studied in depth6,7,9,10,15, HCV epidemiology in Iran remains not well-characterized. Iran is estimated to have the highest population proportion of people who inject drugs (PWID) in MENA16, a key population at high risk of HCV infection. Iran shares a border with Afghanistan, the world’s largest opiates producer17, and therefore has become a major transit country for drug trafficking18. Nearly half of opium, heroine, and morphine seizures globally occur in Iran alone18. Increased availability and lower prices of injectable drugs have led to increased injecting drug use and dependency19,20. Understanding HCV epidemiology in Iran is critical for developing and targeting cost-effective and cost-saving prevention and treatment interventions against HCV.

The aim of this study was to characterize HCV epidemiology in Iran by (1) systematically reviewing and synthesizing records, published and unpublished, of HCV incidence and prevalence among the different population groups, (2) systematically reviewing and synthesizing evidence on HCV genotypes, and (3) estimating pooled mean HCV prevalence among the general population and other key risk populations by pooling available HCV prevalence measures. This study is conducted as part of the MENA HCV Epidemiology Synthesis Project, an on-going effort to characterize HCV epidemiology in MENA, providing empirical evidence to inform key public health research, policy, and programming priorities at the national and regional level5,7,9,21–30.

Materials and Methods

This study follows the methodology used in the previous systematic reviews of the MENA HCV Epidemiology Synthesis Project7,9,21–25,27. The following subsections summarize this methodology while further details can be found in previous publications of this project7,9,21–25,27.

Data sources and search strategy

We systematically reviewed all HCV incidence and prevalence data in Iran as informed by the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook31. We reported our results using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Table S1)32. Our main data sources included PubMed and Embase databases (up to June 27th, 2016), the Scientific Information Database (SID) of Iran (up to June 29th, 2016), the World Health Organization Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR WHO) database (up to July 1st, 2016), and the abstract archive of the International Aids Society (IAS) conferences (up to July 1st, 2016). Additionally, the MENA HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project database was searched for further records in the form of country level reports and routine data33,34. A broad search criteria was used (Fig. S1) with no language restrictions. Articles were restricted to those published after 1989, the year in which HCV was first identified35,36.

Study selection

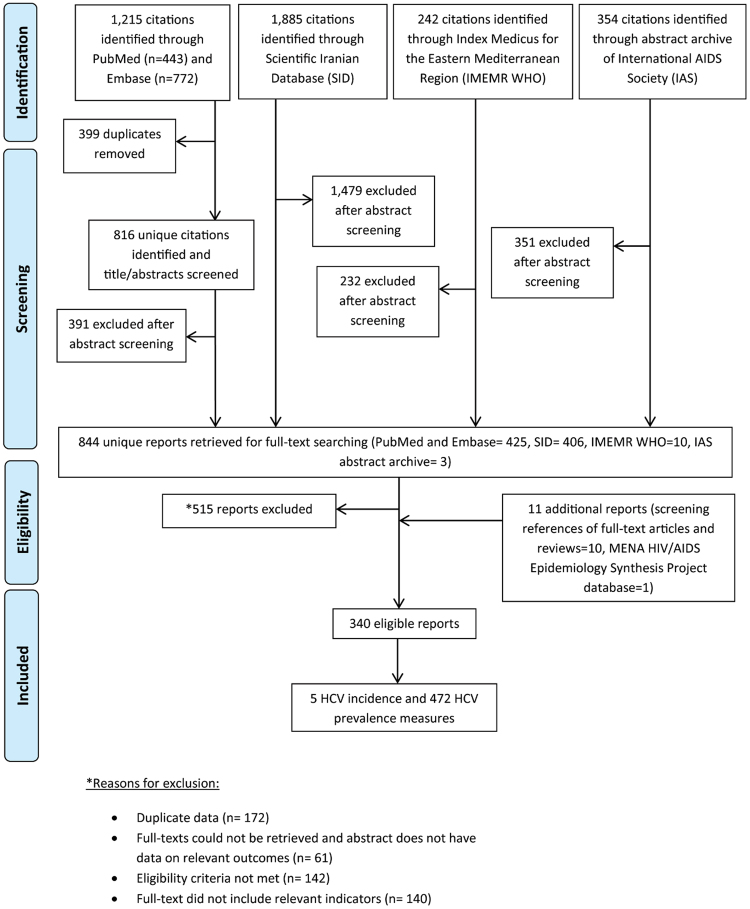

All records identified through our search were imported into a reference manager, Endnote, where duplicate publications were identified and excluded (Fig. 1). Similar to our previous systematic reviews7,9,21–25,27, the remaining unique reports underwent two stages of screening, performed by SM and VA. The titles and abstracts were first screened, and those deemed relevant or potentially relevant underwent further screening, in which the full-texts were retrieved and assessed for eligibility, based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible reports were included in this study, while the remaining ineligible reports were excluded for reasons indicated in Fig. 1. The references of all full-text articles and literature reviews were also screened for further potentially relevant reports.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of article selection for the systematic review of hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence and prevalence in Iran, adapted from the PRISMA 2009 guidelines32.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria used were developed based also on our previous systematic reviews7,9,21–25,27. Briefly, any document, of any language, reporting HCV antibody incidence and/or antibody prevalence in Iran, based on biological assays and on primary data, qualified for inclusion in this review. Our exclusion criteria included case reports, case series, editorials, letters to editors, commentaries, literature reviews, and studies reporting HCV prevalence based on self-reporting and/or on Iranian nationals outside of Iran. Studies performed before 1989, and studies referring to HCV as non-A non-B hepatitis, were also excluded. A secondary independent screening was also performed for articles reporting HCV genotype information, regardless of whether information on HCV incidence and/or prevalence was included.

In the subsequent sections, any document including outcome measures of interest will be referred to as a ‘report’, while details of a specific outcome measure will be referred to as a ‘study’. Accordingly, one report may contribute multiple studies, and multiple reports of the same study (outcome measure) were identified as duplicates and considered as one study.

Data extraction and data synthesis

Data from relevant reports were extracted by SM and VA. To check for consistency in extractions, 37% of reports were double extracted. Nature of extracted data followed our previous HCV systematic reviews7,9,21–25,27. HCV prevalence measures were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 1%, which were rounded to two decimal places. Risk factors for HCV infection (at the individual level), which were found to be statistically significant through multivariable regression analyses, were extracted from all articles, when available.

Risk factors for HCV infection were extracted when identified as significant after controlling for confounders through multivariable regression analyses. Data on HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) prevalence were extracted whenever available in reports including an HCV prevalence measure(s). HCV genotype studies identified through the independent secondary screening were extracted to a separate data file. Extracted data were stratified by study populations’ risk of acquiring HCV infection as follows:

General populations (that is populations at low risk): these consisted of blood donors, pregnant women, children, healthy adults, and army recruits, among other general population groups.

Populations at intermediate risk: these consisted of healthcare workers, household contacts of HCV infected patients, female sex workers, prisoners, homeless people, and drug users (only where the route of drug use was not specified or excluded drug injection), among others. Drug users were classified into the intermediate risk category as we could not assess, with the available information, the extent to which drug injection is common in any such specific population—it is possible that the majority of these drug users were not injecting drugs at the time of the study.

Populations at high risk: these consisted of HIV patients, PWID, and of populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures, such as hemodialysis patients, hemophilia patients, thalassemia, patients, and patients with bleeding disorders.

Special clinical populations: these consisted of populations with liver-related conditions, such as chronic liver disease, acute viral hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver cirrhosis. This also consisted of other special clinical populations for which the level of HCV risk of exposure could not be ascertained a priori, such as lichen planus patients.

Quantitative assessment

The quantitative analyses were conducted following an analysis plan similar to that in our previous HCV systematic reviews7,9,21–25,27. HCV prevalence data in reports comprising at least 50 participants were stratified by risk and summarized using reported prevalence measures. Meta-analyses of HCV prevalence measures were conducted by risk category for studies consisting of a minimum of 25 participants. Stratified measures were used in place of HCV prevalence for the total sample only if the sample size requirement was met for each stratum.

A pre-defined sequential order was followed when considering stratifications. Nationality was prioritized, followed by sex, year, region, and age. One stratification was included per study to avoid double-counting.

The variance of the prevalence measures was stabilized using the Freeman-Tukey type arcsine square-root transformation of the corresponding proportions37. Estimates for HCV prevalence were weighted using the inverse variance method and then pooled using a DerSimonian-Laird random effects model. This model accounts for sampling variation and expected heterogeneity in effect size across studies38. Heterogeneity was assessed using several measures. The forest plots were visually inspected and Cochran’s Q test was conducted, where a p-value < 0.10 was considered significant38,39. The I² and its confidence intervals were calculated38. The prediction intervals were also calculated to estimate the distribution of true effects around the estimated mean38,40.

Univariable and multivariable random-effects meta-regressions, based on established methodology31, were conducted to determine population-level associations with HCV prevalence and sources of between-study heterogeneity. Variables entered into the univariable model included risk population, sample size (<100 or ≥100), study site, sampling methodology (probability-based or nonprobability-based), publication year, and median year of data collection. Variables were included into the final multivariable model if the p-value was <0.10. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the final multivariable meta-regression were considered significant.

The majority of HCV prevalence measures in the general population were among blood donors, a population that mainly includes healthy adults. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis to ascertain the impact of excluding blood donors on our pooled mean estimate for HCV prevalence among the general population (Fig. S5).

Descriptive analyses of HCV genotypes and subtypes were also performed. Individuals with mixed HCV genotypes contributed to the quantification of each identified genotype separately. Meta-analyses of genotype proportions were also performed to estimate the pooled mean proportions for each genotype. The diversity of HCV genotypes was assessed using the Shannon Diversity Index41.

Meta-analyses were performed on R version 3.1.242, using the package meta 43. Meta-regressions were performed on STATA 13, using the metan command44.

Qualitative analysis

Similar to our previous HCV systematic reviews7,9,21–25,27, the quality of each incidence or prevalence measure was determined by assessing sources of bias that may affect the reported measure. The Cochrane approach was used to infer the risk of bias (ROB)31, and the precision of the reported measures was also evaluated. Studies were categorized into low or high ROB based on three quality domains: type of HCV ascertainment (biological assay or otherwise), rigor of sampling methodology (probability-based or nonprobability-based), and response rate (≥80% of the target sample size was reached or otherwise).

Studies with missing information for any of the three domains were categorized as unclear ROB for that specific domain. Studies where HCV measures were obtained from individuals presenting voluntarily to facilities where routine blood screening is conducted, or retrieved from patients’ medical records, were considered as having low ROB on the response rate domain. HCV prevalence measures obtained from country-level routine reporting, with limited description of the methodology used to be able to conduct ROB assessment, were categorized as of unknown quality.

Studies where HCV measures were obtained from a sample size of at least 100 individuals were considered as having high precision. For an HCV prevalence of 1% and a sample size of 100, the 95% confidence interval (CI) is 0–5%; a reasonable CI for an HCV prevalence estimate.

Results

Search results

Figure 1 describes the selection process by which studies were included in this systematic review, adapted from the PRISMA flow diagram32. We identified a total of 3,696 citations: 443 from PubMed, 772 from Embase, 1,885 from SID, 242 from IMEMR WHO, and 354 from the abstract archive of the IAS. After exclusion of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 844 unique reports remained, for which the full-texts were retrieved for full-text screening. After full-text screening, 515 reports were excluded for reasons specified in Fig. 1. An additional 10 records were identified through screening references of full-text articles and reviews. One country-level report was retrieved and included from the MENA HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project database33,34. In total, 340 eligible reports were included in this systematic review. This yielded five HCV incidence measures and 472 HCV prevalence measures.

All 3,696 citations underwent an independent secondary screening for HCV genotype studies (Fig. S2). After title and abstract screening and exclusion of duplicates, the full-texts of 144 reports were screened. In total, 44 reports were found eligible for inclusion in this secondary systematic review, yielding 66 HCV genotype measures.

HCV incidence overview

We identified five incidence measures through our search (Table 1), three of which were conducted in Tehran. The highest sero-conversion risks were observed in thalassemia patients and hemodialysis patients, of 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively45,46. In special clinical populations, HCV incidence was measured in renal transplant patients and impaired glucose tolerance patients. The HCV sero-conversion risks were 2.1% and 0.71%, respectively47,48. In female drug users on methadone treatment (where the route of drug use was not specified) the sero-conversion risk was 2.5%49. No studies reported incidence rate, nor provided sufficient information for incidence rate to be calculated.

Table 1.

Studies reporting hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence in Iran.

| Author, year (citation) | Year of data collection | Study site | Population’s classification based on risk of HCV exposure | Population | Sample size at recruitment | Lost to follow-up | HCV sero-conversion risk (relative to total sample size) | Duration of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pourmand, 200747 | 2002–04 | Hospital | Special clinical population | Renal transplant patients | 141 | 0 | 2.1% | 24 months |

| Jabbari, 200846 | 2005–06 | Hospital | High risk population | Hemodialysis patients | 70 | 0 | 4.3% | 18 months |

| Azarkeivan, 201245 | 1996–09 | Blood transfusion center | High risk population | Thalassemia patients | 307 | 0 | 6.8% | 168 months |

| Dolan, 201249 | 2007–08 | Rehab center | Intermediate risk population | Female drug users on methadone treatment | 78 | 38 | 2.5% | 7 months |

| Bahar, 200748 | 1998–01 | Hospital | Special clinical population | Impaired glucose tolerance patients | 560 | 0 | 0.71% | 36 months |

HCV prevalence overview

General population

A total of 122 HCV prevalence measures were identified in the general population (Table 2), ranging from 0.0% to 3.1%, with a median of 0.3%. Most measures were obtained from blood donors (n = 72) where HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 3.1%, with a median of 0.3%. In pregnant women (n = 6), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 0.8%, with a median of 0.3%. In other general populations (n = 44), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 2.4%, with a median of 0.5%.

Table 2.

Studies reporting hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence among the general population (populations at low risk) in Iran.

| Author, year (citation) | Year(s) of data collection | City or country of survey | Study site | Study design | Study sampling procedure | Population | Sample size | HCV prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afzali, 2003108 | 1996 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 6,669 | 0.37 |

| Afzali, 2003108 | 1997 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 6,750 | 0.64 |

| Afzali, 2003108 | 1998 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 6,922 | 0.59 |

| Afzali, 2003108 | 1999 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 6,986 | 1.6 |

| Afzali, 2003108 | 2001 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 7,721 | 1.7 |

| Afzali, 2003108 | 2000 | Kashan | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 8,683 | 1.5 |

| Aghanjanipoor, 2006109 | 2002 | Babol | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 16,576 | 0.48 |

| Alavi, 2012110 | NS | Tehran | NS | CC | Conv | Healthy children | 90 | 0.00 |

| Alavian, 2002111 | 1996–1998 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 319,375 | 0.09 |

| Alavian, 2015112 | 2012 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | Conv | Healthy adults | 275 | 0 |

| Amini, 2005113 | NS | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 100 | 0.00 |

| Ansar, 2002114 | 1997–1998 | Rasht | Blood transfusion center | CS | SRS | Blood donors | 5,976 | 0.03 |

| Ansari-Moghaddam, 2012115 | 2008–2009 | Zahedan | Primary health care centers (community) | CS | Cluster sampling | Residents (male) | 1,207 | 0.66 |

| Ansari-Moghaddam, 2012115 | 2008–2009 | Zahedan | Primary health care centers (community) | CS | Cluster sampling | Residents (female) | 1,380 | 0.36 |

| Ardebili, 2012116 | 2007–2011 | Kavar | Community | CS | Conv | General population | 6,095 | 0.24 |

| Arfaee, 2002117 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Veterans | 307 | 0.97 |

| Assarehzadegan, 2008118 | 2005 | Khuzestan | Blood bank | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 400 | 0.00 |

| Babak, 2008119 | 2006 | Kermanshah | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | Residents | 1,721 | 0.87 |

| Barhaghtalab, 2008120 | 2002–2007 | Fasa | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 25,491 | 0.55 |

| Bozorgi, 2012121 | 2009 | Ghazvin | Blood bank | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 20,591 | 0.17 |

| Chamani, 2007122 | 2004 | Tehran | Fertility clinic/IVF | NS | NS | Infertile individuals (female) | 533 | 0.40 |

| Chamani, 2007122 | 2004 | Tehran | Fertility clinic/IVF | CS | NS | Infertile individuals (male) | 716 | 0.00 |

| Delavari, 2004123 | 2003 | Kerman | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors (female) | 2,921 | 0.10 |

| Delavari, 2004123 | 2003 | Kerman | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors (male) | 12,331 | 0.46 |

| Doosti, 2009124 | 2003–2004 | Shahre-Kord | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 11,200 | 0.59 |

| Emam, 2006125 | 2001–2003 | Jahrom | Blood bank | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 3,000 | 0.30 |

| EMRO, 2011126 | 2011 | National | National | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 1,986,992 | 0.06 |

| Esfandiarpour, 2005127 | 2002–2003 | Kerman | NS | CC | NS | General population | 149 | 1.3 |

| Esmaeili, 2004128 | 2004 | Babol | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | NS | Children not receiving blood | 100 | 0.00 |

| Esmaeili, 2004128 | 2004 | Babol | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | NS | Children receiving blood | 100 | 2.0 |

| Esmaeili, 2009129 | 2006–2007 | Bushehr | NS | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 20,294 | 0.21 |

| Farajzadeh, 2005130 | 2001–2002 | Kerman | Blood transfusion center | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 96 | 3.1 |

| Farshadpour, 2010131 | 2007–2007 | Ahvaz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 2,376 | 2.3 |

| Farshadpour, 2016132 | 2004–2014 | Bushehr | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 293,454 | 0.10 |

| Gachkar, 2015133 | 2004 | Tabriz | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors (male) | 399 | 0.00 |

| Gerayli, 2015134 | 2012 | Mashhad | Medical Laboratory | CC | Conv | Healthy adults | 134 | 0 |

| Ghaderi, 2007135 | 2004–2006 | Birjand | NS | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 150 | 0.67 |

| Ghadir, 2006136 | NS | Golestan | Community | NS | NS | General population (male) | 736 | 0.18 |

| Ghadir, 2006136 | NS | Golestan | Community | NS | NS | General population (female) | 1,387 | 0.85 |

| Ghafouri, 2011137 | 2006–2009 | South Khorasan | NS | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 95,538 | 0.01 |

| Ghavanini, 2000138 | 1998 | Shiraz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 7,879 | 0.59 |

| Ghezeldasht, 2015139 | 2009–2010 | Khorasan Razavi | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 1,227 | 0.57 |

| Habibzadeh, 2005140 | 2003 | Ardabil | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 441 | 0.23 |

| Hajiani, 2006141 | 2003–2004 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CC | NS | Blood donors | 500 | 1.2 |

| Hajiani, 2006142 | 1998–2003 | Ahvaz | NS | CC | Conv | Healthy adults | 360 | 1.0 |

| Heydarabad, 2012143 | 2010–2012 | Malekan | NS | NS | NS | Pregnant women | 420 | 0.48 |

| Hosseien, 2009144 | 2003–2005 | Tehran | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 1,004,889 | 2.1 |

| Hosseini, 2007145 | 2005 | Boushehr | NS | NS | NS | Blood donors | 19,627 | 0.23 |

| Jadali, 2005146 | NS | Tehran | NS | CC | NS | Healthy individuals | 50 | 0.00 |

| Jadali, 2005147 | NS | NS | NS | CC | Conv | Healthy individuals | 50 | 0.00 |

| Jamali, 2008148 | 2006 | Golestan | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 2,049 | 1.0 |

| Kafi-abad, 2009149 | 2004–2007 | National | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 6,499,851 | 0.13 |

| Karim, 2008150 | 2003–2005 | Ahvaz | Blood transfusion center | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 125 | 2.4 |

| Karimi, 2008151 | 2004–2006 | Shahre-Kord | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 35,124 | 0.20 |

| Kasraian, 2008152 | 2007–2008 | Shiraz | Blood transfusion center | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 93,987 | 0.21 |

| Kasraian, 2010153 | 2003 | Shiraz | Blood transfusion center | Pre-post | Conv | Blood donors (post-earthquake) | 239 | 0.84 |

| Kasraian, 2010153 | 2003 | Shiraz | Blood transfusion center | Pre-post | Conv | Blood donors (pre-earthquake) | 1,694 | 0.47 |

| Kasraian, 2015154 | 2002 | Shiraz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | NS | 0.19 |

| Kasraian, 2015154 | 2003 | Shiraz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | NS | 0.13 |

| Kasraian, 2015154 | 2004 | Shiraz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | NS | 0.09 |

| Kasraian, 2015154 | 2005 | Shiraz | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | NS | 0.16 |

| Kavoosi, 2008155 | 2004–2005 | Kermanshah | NS | CC | Conv | Healthy adults | 57 | 1.7 |

| Kazeminejad, 2005156 | 2003 | Gorgan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 38,920 | 0.19 |

| Keshvari, 2015157 | 2008 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 296,567 | 0.14 |

| Keshvari, 2015157 | 2013 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 282,010 | 0.07 |

| Khedmat, 2007158 | 2005–2006 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CS | SRS | Blood donors | 1,014 | 2.1 |

| Khodabandehloo, 2013159 | 2008–2011 | Semnan | NS | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 124,704 | 0.03 |

| Kordi, 2011160 | NS | Tehran | Community | CC | Cluster sampling | Volleyball and soccer players | 410 | 0.00 |

| Kordi, 2011160 | NS | Tehran | Community | CC | Cluster sampling | Wrestlers (male) | 420 | 0.48 |

| Mahmoudian, 2006161 | 2003–2004 | Mixed (28 provinces unspecified) | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 1,489,935 | 0.07 |

| Maneshi, 2010162 | 2004–2008 | Bushehr | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 51,884 | 0.33 |

| Mansour-Ghanaei, 2007163 | 1998–2003 | Guilan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 221,508 | 0.32 |

| Masaeli, 2006164 | 2002–2003 | Isfahan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 29,458 | 0.24 |

| Merat, 201054 | 2006 | Mixed (Golestan, Tehran, Hormozgan) | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 5,684 | 0.88 |

| Metanet, 2006165 | 2004 | Zahedan | NS | CC | Conv | Blood donors | 1,399 | 0.07 |

| Moezzi, 2015166 | NS | Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | Community | CS | Single stage cluster sampling | Adults | 3,000 | 1.4 |

| Mogaddam, 2010167 | NS | Ardabil | Blood bank | CC | NS | Blood donors | 60 | 0.00 |

| Mohammadali, 2014168 | 2005–2011 | Tehran | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 2,031,451 | 0.39 |

| Mohebbi, 2011169 | 2007–2008 | Lorestan | Primary health care centers (community) | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | 827 | 0.24 |

| Moniri, 2004170 | 2001–2002 | Kashan | Blood bank | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 600 | 0.50 |

| Monsour-Ghanaei, 200773 | 2003 | Guilan | Community | CS | Conv | Residents of nursing home | 383 | 2.3 |

| Moradi, 2007171 | 2001–2002 | Saravan city, Sistan and Baluchistan | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | Women in childbearing ages | 356 | 0.84 |

| Motlagh, 2001172 | 1999–2000 | Ahvaz | NS | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | 80 | 0.00 |

| Mousavi, 2010173 | 2008 | Khuzestan | Clinical setting (hospital) | CS | Conv | Renal transplant donors | 79 | 0.00 |

| Mousavi, 2011174 | 2009–2010 | Ahvaz | Clinical setting (hospital) | CS | Conv | Renal transplant donors | 52 | 0.00 |

| Pourshams, 2005175 | 2001 | Tehran | Blood bank | CS | SRS | Blood donors | 1,959 | 0.46 |

| Poustchi, 201156 | NS | Golestan | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 49,338 | 0.50 |

| Rahbar, 2004176 | 2001–2002 | Mashhad | Blood transfusion center | CS | NS | Blood donors | 60,892 | 0.10 |

| Rahnama, 2005177 | 2000–2001 | Kerman | Regional blood transfusion center | CC | SRS | Blood donors | 140 | 2.1 |

| Razjou, 2012178 | 2009 | National | Blood bank | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 1,494,282 | 0.13 |

| Rezaie, 2016179 | 2011–2015 | Semnan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 42,253 | 0.06 |

| Rezazadeh, 2006180 | 2004–2005 | Hamadan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 18,306 | 0.43 |

| Roshan, 2012181 | 2007–2008 | Ahvaz | Fertility clinic/IVF | CS | Conv | Infertile couples (male) | 712 | 0.84 |

| Roshan, 2012181 | 2007–2008 | Ahvaz | Fertility clinic/IVF | CS | Conv | Infertile couple (female) | 712 | 0.42 |

| Salehi, 2011182 | 2002–2006 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 4,808 | 0.27 |

| Samadi, 2014183 | 2012 | Ahvaz | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 2,108 | 0.00 |

| Seyed-Askari, 2015184 | 2009–2013 | Kerman | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 360,722 | 0.08 |

| Shaheli, 2015185 | 2012 | Shiraz | Community | CC | Conv | Healthy adults | 100 | 0 |

| Shahshahani, 2013186 | 2004–2010 | Yazd | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 346,471 | 0.07 |

| Shakeri, 2013187 | 2010–2011 | Mashhad | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 3,870 | 0.13 |

| Shamsdin, 2012188 | 2010–2011 | Shiraz | Community | CS | Conv | General population | 2,080 | 0.72 |

| Sofian, 2010189 | 2008 | Arak | Regional blood transfusion center | CS | SRS | Blood donors | 531 | 0.19 |

| Sohrabpour, 2010190 | NS | Mixed (Hormozgan, Tehran, Golestan) | Community | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 5,589 | 0.88 |

| Tahereh, 2005191 | 2000–2002 | Ghazvin | Blood transfusion center | CS | SRS | Blood donors | 39,598 | 0.25 |

| Taheri, 2008192 | 2003–2005 | Rasht | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 49,820 | 0.18 |

| Tajbakhsh, 2007193 | 2004 | Shahrekord | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 11,472 | 0.60 |

| Tanomand, 2007194 | 2005 | Malekan city | Clinical setting (hospital) | CS | SRS | General population | 346 | 0.29 |

| Vahidi, 2000195 | 1996 | Kerman | Clinical setting (hospital) | CC | Conv | Healthy children | 107 | 0.00 |

| Yazdani, 2006196 | 1998–2000 | Kermanshah | Clinical setting (hospital) | CS | Conv | Pregnant women | 2,000 | 0.60 |

| Zamani, 2013197 | 2008–2011 | Mazandaran | Primary health care centers (community) | CS | Cluster sampling | General population | 6,145 | 0.08 |

| Zanjani, 2013198 | 2005–2006 | Zanjan | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Blood donors | 29716 | 0.11 |

aAbbreviations: CC, case-control; Conv, convenience; CS, cross-sectional; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (WHO); IVF, in vitro fertilization; NS, not specified, SRS; simple random sampling.

bThe decimal places of the prevalence figures are as reported in the original reports, but prevalence figures with more than one decimal places were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 1%.

Populations at high risk

A total of 208 HCV prevalence measures were identified in populations at high risk (Table 3), ranging from 0.0% to 90.0%, with a median of 26.3%. The majority were conducted on high risk clinical populations (n = 127). In hemophilia patients (n = 25), HCV prevalence ranged from 6.0% to 90.0%, with a median of 54.0%. In thalassemia patients (n = 58), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 68.9%, with a median of 16.6%. In hemodialysis patients (n = 41), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 31.4%, with a median of 8.3%. In HIV positive patients (n = 25), HCV prevalence ranged from 3.9% to 89.3%, with a median of 67.7%. Among PWID (n = 56), HCV prevalence ranged from 11.3% to 88.9%, with a median of 51.4%.

Table 3.

Studies reporting hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence among populations at high risk in Iran.

| Author, year (citation) | Year(s) of data collection | City or country of survey | Study site | Study design | Study sampling procedure | Population | Sample size | HCV prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdollahi, 2008199 | 2003 | NS | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 174 | 83.3 |

| Aghakhani, 2009200 | NS | Tehran | NS | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 106 | 67.0 |

| Aghakhani, 2009200 | NS | Tehran | NS | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 289 | 3.1 |

| Akbari, 2011201 | 2003–2004 | Shiraz | Thalassemia center | CC | SRS | Thalassemia patients | 200 | 25.0 |

| Alavi, 2005202 | 2002 | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 110 | 11.8 |

| Alavi, 2007203 | 2001–2003 | Ahvaz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID with HIV | 104 | 74.0 |

| Alavi, 2009204 | 2001–2006 | Ahvaz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 142 | 52.1 |

| Alavi, 2012110 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | Conv | Thalassemia patients (<18) | 90 | 13.3 |

| Alavia, 2003205 | NS | Ghazvin | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | NS | NS | Thalassemia patients | 95 | 24.2 |

| Alavian, 2003206 | 2000–2001 | NS | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 176 | 60.2 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 1999 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 14.4 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2000 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 11.2 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2001 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 8.8 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2002 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 8.2 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2003 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 6.7 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2004 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 5.6 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2005 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 4.8 |

| Alavian, 200894 | 2006 | National | NS | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | NS | 4.5 |

| Alavian, 2015112 | 2012 | Isfahan | Hemodialysis units | CC | Conv | Hemodialysis units | 274 | 0 |

| Alipour, 201361 | 2003–2011 | Shiraz | Counseling centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients (male) | 215 | 17.7 |

| Alipour, 201361 | 2003–2011 | Shiraz | Counseling centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients (female) | 1,230 | 89.1 |

| Alipour, 2013207 | NS | Mixed (Shiraz, Tehran, Mashhad) | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID (male) | 226 | 38.6 |

| Alipour, 201367 | 2011 | Shiraz | Counseling centers | CS | SRS | HIV patients | 168 | 87.5 |

| Alizadeh, 2005208 | 2002 | Hamedan | Prison | CS | SRS | PWID | 149 | 31.5 |

| Alizadeh, 2006209 | NS | Hamadan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | NS | Hemophilia patients | 66 | 59.1 |

| Ameli, 2008210 | 2006 | Mazandaran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 65 | 16.9 |

| Amin-Esmaeili, 201257 | 2006–2007 | Tehran | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 895 | 34.5 |

| Amiri, 2005211 | 2001 | Guilan | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 298 | 24.8 |

| Ansar, 2002114 | 1997–1998 | Rasht | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | SRS | Thalassemia patients (female) | 50 | 62.0 |

| Ansar, 2002114 | 1997–1998 | Rasht | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | SRS | Thalassemia patients (male) | 55 | 65.0 |

| Ansar, 2002114 | 1997–1998 | Rasht | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | SRS | Hemophilia patients | 93 | 55.9 |

| Ansari, 2007212 | 2005–2006 | Shiraz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients (female) | 400 | 16.0 |

| Ansari, 2007212 | 2005–2006 | Shiraz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients (male) | 406 | 12.8 |

| Asl, 2013213 | 2003–2005 | Alborz | Prisons | Coh | Conv | PWID | 150 | 69.3 |

| Assarehzadegan, 2012214 | 2008–2009 | Ahvaz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 87 | 54.0 |

| Ataei, 2010215 | 2008–2009 | Isfahan | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 3,284 | 38.0 |

| Ataei, 201053 | 1998–2007 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 130 | 77.0 |

| Ataei, 2011216 | NS | Isfahan | Prison, drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 1,485 | 43.4 |

| Ataei, 2011217 | NS | Isfahan | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 136 | 19.8 |

| Ataei, 2012218 | 1996–2011 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 463 | 8.0 |

| Azarkeivan, 2010219 | 1996–2005 | Tehran | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 395 | 27.5 |

| Azarkeivan, 2011220 | 2008 | Tehran | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 695 | 24.5 |

| Azarkeivan, 201245 | 1996–2009 | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | Coh | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 395 | 7.6 |

| Babamahmoodi, 2012221 | 2008–2010 | Mazandaran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 80 | 58.8 |

| Basiratnia, 2010222 | 1999 | Shahrekord | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | NS | NS | Thalassemia patients (female) | 50 | 22.0 |

| Basiratnia, 2010222 | 1999 | Shahrekord | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | NS | NS | Thalassemia patients (male) | 63 | 23.8 |

| Boroujerdnia, 2009223 | 2006–2007 | Khuzestan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 206 | 28.1 |

| Bozorghi, 2006224 | 2004 | Ghazvin | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 89 | 6.7 |

| Bozorgi, 2008225 | 2005 | Ghazvin | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 207 | 24.2 |

| Broumand, 2002226 | NS | Tehran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 548 | 19.6 |

| Company, 2007227 | 2005–2006 | Ahvaz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 195 | 20.5 |

| Dadgaran, 2005228 | NS | Guilan | Hemodialysis units | NS | NS | Hemodialysis patients | 393 | 17.8 |

| Dadmanesh, 2015229 | 2012–2013 | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 138 | 0 |

| Davarpanah, 2013230 | 2006–2007 | Shiraz | Counseling centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 226 | 86.7 |

| Davoodian, 2009231 | 2002 | Tehran | Prisons | CS | SRS | PWID | 249 | 64.8 |

| Eghbalian, 2000232 | NS | Hamedan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | NS | Thalassemia patients (<15) | 53 | 34.0 |

| Esfahani, 2014233 | 2012 | Hamedan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 89 | 49.4 |

| Eskandarieh, 2013234 | NS | Tehran | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 258 | 65.9 |

| Eslamifar, 2007235 | 2006 | Tehran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 77 | 6.5 |

| Etminani-Esfahani, 2012236 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 98 | 55.1 |

| Faramarzi, 2013237 | 2010 | Shiraz | Voluntary counseling center | CS | Conv | HIV patients (male) | 222 | 64.0 |

| Faranoush, 2006238 | 2002 | Mixed (Semnan, Damaghan, Garmsar) | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 630 | 39.7 |

| Farhoudi, 2016239 | 2013–2014 | Tehran | Prison | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 56 | 89.3 |

| Ghaderi, 1996240 | NS | Fars | Blood transfusion center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 90 | 68.5 |

| Ghadir, 2009241 | 2008 | Qom | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 90 | 21.1 |

| Ghafoorian-Broujerdnia, 2006242 | 1999–2004 | Ahvaz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 122 | 26.2 |

| Ghane, 2012243 | 2010 | Mixed (Mazandaran and Guilan) | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 245 | 14.7 |

| Haghazali, 2011244 | 2007 | Ghazvin | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients (males) | 76 | 7.5 |

| Hamissi, 2011245 | 2009 | Ghazvin | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 195 | 6.7 |

| Hariri, 2006246 | 2004 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 120 | 64.0 |

| Hariri, 2006246 | 2004 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 616 | 10.9 |

| Honarvar, 2013247 | 2012–2013 | Shiraz | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 233 | 40.3 |

| Hosseini, 201063 | 2006 | Tehran | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 417 | 80.0 |

| Imani, 2008248 | 2004 | Shahr-e-Kord | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 133 | 11.3 |

| Ismail, 2005249 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 65 | 17.0 |

| Jabbari, 200846 | 2005–2006 | Golestan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 93 | 24.7 |

| Joukar, 2011250 | 2009 | Guilan | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 514 | 11.9 |

| Kaffashian, 2011251 | NS | Isfahan | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 951 | 42.0 |

| Kalantari, 2011252 | 2008–2010 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 545 | 9.1 |

| Kalantari, 2011252 | 2008–2010 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 615 | 80.5 |

| Kalantari, 2014253 | 2010–2011 | Isfahan | Hemodialysis units | CS | Cluster sampling | Hemodialysis patients | 499 | 5.2 |

| Karimi, 2001254 | 1999–2001 | Shiraz | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 466 | 15.7 |

| Karimi, 2001255 | 1999–2001 | Shiraz | Hemophilia unit | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 281 | 15.7 |

| Karimi, 2002256 | 2002 | Shiraz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Coagulation disorder patients | 367 | 13.1 |

| Kashef, 2008257 | NS | Tabriz | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 131 | 18.3 |

| Kassaian, 2011258 | 2009 | Isfahan | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 570 | 10.5 |

| Kassaian, 2011258 | 2009 | Isfahan | Hemodialysis unit | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 800 | 2.1 |

| Kassaian, 201258 | 2009 | Isfahan | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 943 | 41.6 |

| Keramat, 2011259 | 2005–2007 | Hamadan | Counseling center | CS | Conv | PWID | 199 | 63.3 |

| Keshvari, 2014260 | 2008–2010 | Tehran | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 257 | 40.1 |

| Khani, 2003261 | 2001 | Zanjan | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 346 | 50.9 |

| Kheirandish, 200952 | 2006 | Tehran | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 454 | 80.0 |

| Khorvash, 2008262 | 2005 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 92 | 74.3 |

| Khosravi, 2010263 | NS | Shiraz | Counseling center | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 101 | 86.1 |

| Kiakalayeh, 2013264 | 2002–2011 | Rasht | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 1,113 | 10.5 |

| Lak, 2000265 | NS | Tehran | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 100 | 90.0 |

| Lak, 2000265 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | VWD patient | 385 | 55.1 |

| Langarodi, 2011266 | 2009–2010 | Karaj | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 206 | 14.1 |

| Mahdaviani, 2008267 | 2004 | Markazi | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 68 | 36.7 |

| Mahdaviani, 2008267 | 2004 | Markazi | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 97 | 7.2 |

| Mahdavimazdeh, 2009268 | 2005 | Tehran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 2,403 | 9.5 |

| Mak, 2001269 | NS | Isfahan | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 86 | 31.1 |

| Makhlough, 2008270 | 2006 | Sari and Ghaemshahr, Mazandaran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 186 | 11.3 |

| Mansour-Ghanaei,2002271 | 1999 | Guilan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 101 | 71.3 |

| Mansour-Ghanaei,2009272 | 2007 | Rasht | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 163 | 10.4 |

| Mansour-Ghanaei,2009273 | NS | Guilan | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 370 | 50.4 |

| Mashayekhi, 2011274 | 2008–2009 | Tabriz | Thalassemia center | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 100 | 3.0 |

| Mehrjerdi, 201468 | 2011 | Tehran | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 209 | 26.8 |

| Meidani, 2009275 | 2007–2008 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 150 | 26.0 |

| Mirahmadizadeh, 2004276 | NS | Shiraz | NS | CS | NS | PWID | 186 | 80.1 |

| Mirahmadizadeh, 2009277 | NS | National | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | SRS | PWID | 1,531 | 43.4 |

| Mirmomen, 2006278 | 2002 | Mixed (Tehran, Kerman, Ghazvin, Semnan, Zanjan) | Blood transfusion centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 732 | 19.6 |

| Mir-Nasseri, 200562 | 2001–2002 | Tehran | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | NS | PWID | 467 | 66.0 |

| Mir-Nasseri, 201155 | 2001–2002 | Tehran | Prison, drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 518 | 69.3 |

| Mobini, 2010279 | 2006 | Yazd | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 77 | 49.4 |

| Mohammadi, 2009280 | 2007–2008 | Lorestan | NS | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 391 | 72.1 |

| Momen-Heravi, 2012281 | NS | Kashan | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Cluster sampling | PWID | 300 | 47.3 |

| Mousavi, 2002282 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | Thalassemia patients | 81 | 27.2 |

| Mousavian, 2011283 | 2003–2005 | Tehran | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 1,095 | 72.3 |

| Naini, 2007284 | 1993–2006 | Isfahan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 553 | 22.6 |

| Najafi, 2001285 | 1998 | Qaemshahr | Thalassemia centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 100 | 18.0 |

| Rahbar, 2004176 | 2001 | Mashhad | Prison | CC | Conv | PWID | 101 | 59.4 |

| Rahimi-Movaghar, 2010286 | 2006–2007 | Tehran | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Snowball sampling | PWID | 899 | 34.5 |

| Ramezani, 2008287 | 2005–2006 | Tehran | Counseling center | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 171 | 52.6 |

| Ramezani, 2009288 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 91 | 68.5 |

| Ramzani, 2014289 | 2012 | Arak | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 100 | 56.0 |

| Rostami, 2013290 | 2010–2011 | Mixed | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 3963 | 1.3 |

| Rostami-Jalilian, 2006291 | 2002–2004 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID with thrombosis | 72 | 45.8 |

| Rostami-Jalilian, 2006291 | 2002–2004 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID without thrombosis | 76 | 34.2 |

| Sabour, 2003292 | 1999–2000 | Kermanshah | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 140 | 26.4 |

| Saleh, 2011293 | 2007–2008 | Hamedan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | Conv | PWID (corpses) | 94 | 60.6 |

| Salehi, 201569 | 2006–2011 | Shiraz | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 1,327 | 13.5 |

| Sali, 2013294 | 2010–2012 | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 200 | 71.0 |

| Samak, 2012295 | 2007 | Qom | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 142 | 13.4 |

| Samarbaf-Zadeh, 2015296 | NS | Khuzestan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 430 | 9.1 |

| Samimi-Rad, 2007297 | 2004 | Markazi | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients (male) | 50 | 4.0 |

| Samimi-Rad, 2007297 | 2004 | Markazi | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Patients with Inherited bleeding disorder | 76 | 43.4 |

| Samimi-Rad, 2007298 | 2005 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 50 | 100.0 |

| Samimi-Rad, 2007298 | 2005 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 53 | 100.0 |

| Samimi-Rad, 2008299 | 2005 | Markazi | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 204 | 4.9 |

| Sanei, 2004300 | 2002 | Zahedan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 364 | 13.5 |

| Sani, 2012301 | 2007–2009 | Mashhad | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 62 | 71.0 |

| Sarkari, 201259 | 2009–2010 | Mixed (Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad) | NS | CS | Conv | PWID | 158 | 42.2 |

| SeyedAlinaghi, 2011302 | 2004–2005 | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 201 | 67.2 |

| Seyrafian, 2006303 | 2005 | Isfahan | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 556 | 2.9 |

| Shahshahani, 2006304 | NS | Yazd | NS | CS | NS | Hemophilia patients | 74 | 48.6 |

| Shahshahani, 2006304 | NS | Yazd | NS | CS | NS | Thalassemia patients | 85 | 9.4 |

| Sharif, 2009305 | 2001–2006 | Kashan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 200 | 12.0 |

| Sharifi-Mood, 2006306 | 1986–2005 | Zahedan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 74 | 31.1 |

| Sharifi-Mood, 2007307 | 2003–2006 | Zahedan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 81 | 29.6 |

| Siavash, 2008308 | 2007 | Kermanshah | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | HIV patients | 888 | 3.9 |

| Sofian, 2012309 | 2009 | Markazi | Prison | CS | Conv | PWID | 153 | 59.5 |

| Somi, 2007310 | 2006 | Tabriz | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 462 | 14.9 |

| Somi, 2014311 | 2012 | Tabriz | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 455 | 8.1 |

| Taremi, 2005312 | 2004 | Tabriz | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 324 | 20.4 |

| Tayeri, 2008313 | 2000–2007 | Isfahan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | PWID with HIV | 106 | 75.5 |

| Taziki, 2008314 | 2001 | Mazandaran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 348 | 18.0 |

| Taziki, 2008314 | 2006 | Mazandaran | Hemodialysis units | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 497 | 12.0 |

| Toosi, 2007315 | NS | Tehran | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 130 | 8.5 |

| Torabi, 2005316 | 2003 | Azerbaijan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Thalassemia patients (<18) | 84 | 7.1 |

| Torabi, 2006317 | 2003 | Azerbaijan | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 130 | 55.4 |

| Vahidi, 2000195 | 1996 | Kerman | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CC | Conv | Thalassemia patients | 107 | 22.4 |

| Valizadeh, 2013318 | 2010 | Urmia | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 50 | 6.0 |

| Yazdani, 2012319 | 1996–2010 | Isfahan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 350 | 66.0 |

| Zadeh, 2007320 | 2007 | Tehran | NS | CS | Conv | PWID (males) | 70 | 36.0 |

| Zahedi, 2004321 | 2002 | Kerman | Clinical: hospital & health care centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 97 | 44.3 |

| Zahedi, 2012322 | 2010 | Kerman | Hemodialysis centers | CS | Conv | Hemodialysis patients | 228 | 3.0 |

| Zali, 2001323 | 1995 | Tehran | Prison | CS | SRS | PWID (male) | 402 | 45.0 |

| Zamani, 200751 | 2004 | Tehran | Community, drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | PWID | 202 | 52.0 |

| Zamani, 201064 | 2008 | Foulad-Shahr City | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Snowball sampling | PWID | 117 | 60.7 |

| Ziaee, 2005324 | 2000 | Khorasan | Drop in centers and rehab centers | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 80 | 55.0 |

| Ziaee, 2007325 | NS | South Khorassan | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 80 | 26.3 |

| Ziaee, 2015326 | 2010–2012 | Birjand | Hemophilia units | CS | Conv | Hemophilia patients | 108 | 20.4 |

aAbbreviations: CC, case-control; Coh, cohort; Conv, convenience; CS, cross-sectional; NS, not specified; PWID, people who inject drugs; SRS, simple random sampling; VWD, von Willebrand disease.

bThe decimal places of the prevalence figures are as reported in the original reports, but prevalence figures with more than one decimal places were rounded to one decimal place, with the exception of those below 1%.

Populations at intermediate risk

A total of 70 HCV prevalence measures were identified in intermediate risk populations (Table S2), ranging from 0.0% to 48.0%, with a median of 3.3%. In prisoners (n = 15), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.7% to 37.9%, with a median of 4.1%. In homeless people (n = 10), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 48.0%, with a median of 3.0%. Half of these studies were conducted on homeless children, among which HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 3.5%, with a median of 1.0%. In household contacts of HCV index patients (n = 5), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 3.3%, with a median of 2.2%. In healthcare workers (n = 11), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 37.0%, with a median of 0.0%. In drug users (where the route of drug use was not specified (n = 13), HCV prevalence ranged from 3.4% to 36.1%, with a median of 14.5%.

Special clinical populations

A total of 72 HCV prevalence measures were identified in special clinical populations (Table S3), ranging from 0.0% to 69.1%, with a median of 3.2%. In hepatitis B virus patients, prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 18.0%, with a median of 10.3%. In viral hepatitis patients (n = 9), HCV prevalence ranged from 0.0% to 34.9%, with a median of 6.1%. In patients with liver cirrhosis (n = 5), HCV prevalence ranged from 1.7% to 14.9%, with a median of 7.3%.

Pooled mean HCV prevalence estimates

Table 4 shows the results of our meta-analyses for HCV prevalence. The estimated national population-level HCV prevalence, based on the pooled HCV prevalence in the general population, was 0.3% (95% CI: 0.2–0.4%). There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (p < 0.0001). I2 was estimated at 99.8% (95% CI: 99.8–99.8%), indicating that almost all observed variation is attributed to true variation in HCV prevalence rather than sampling error. The prediction interval was 0.0–1.5%.

Table 4.

Results of the meta-analyses for hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence measures in Iran stratified by populations’ risk of exposure.

| Population at risk | Studies | Samples | HCV prevalence | Heterogeneity measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | Total n | Range (%) | Mean (%) | 95% CI | Q (p-value)ª | I² (confidence limits)c | Prediction interval (%)d | ||

| General population (populations at low risk) | 122 | 16,073,479 | 0.0–3.1 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.4 | 56269.6 (p < 0.0001) | 99.8% (99.8–99.8%) | 0.0–1.5 | |

| Populations at high risk | 208 | 55,257 | 0.0–90.0 | 32.1 | 28.1–36.2 | 217272.1 (p < 0.0001) | 99.0% (99.0–99.1%) | 0.0–88.5 | |

| PWID | 56 | 17,999 | 11.3–88.9 | 52.2 | 46.9–57.5 | 2615 (p < 0.0001) | 97.9% (97.6–98.1%) | 15.8–87.3 | |

| Populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures | 127 | 32,517 | 0.0–90.0 | 20.0 | 16.4–23.9 | 8786.2 (p < 0.0001) | 98.6% (98.5–98.8%) | 0.0–69.7 | |

| Populations at intermediate risk | 70 | 36,879 | 0.0–48.0 | 6.2 | 3.4–9.6 | 9,128 (p < 0.0001) | 99.2% (99.2–99.3%) | 0.0–49.9 | |

| Special clinical populations | 72 | 55,187 | 0.0–69.1 | 4.6 | 3.2–6.1 | 2293.6 (p < 0.0001) | 96.9% (96.5–97.3%) | 0.0–21.6 | |

| Populations with liver-related conditions | 28 | 6,338 | 0.0–34.9 | 7.5 | 4.3–11.4 | 639.5 (p < 0.0001) | 95.8% (94.8–96.6%) | 0.0–35.2 | |

| Other special clinical populations | 44 | 48,849 | 0.0–69.1 | 2.7 | 1.8–3.6 | 520.6 (p < 0.0001) | 91.7% (89.8–93.3%) | 0.0–9.6 | |

aAbbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

bQ: Cochran Q statistic assessing the existence of heterogeneity in HCV prevalence estimates.

cI²: a measure assessing the magnitude of between-study variation that is due to difference in HCV prevalence estimates across studies rather than chance.

dPrediction interval: a measure estimating the 95% interval in which the true HCV prevalence in a new HCV study will lie.

The pooled mean HCV prevalence for populations at high risk was 32.1% (96% CI: 28.1–36.2%). There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), with an I2 of 99.0% (95% CI: 99.0–99.1%). The prediction interval was 0.0–88.5%. For the subpopulations of PWID and populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures, the pooled means were 52.2% and 20.0%, respectively.

The pooled mean HCV prevalence for populations at intermediate risk was 6.2% (95% CI: 3.4–9.6%). There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), with an I2 of 99.2% (95% CI: 99.2–99.3%). The prediction interval was 0.0–49.9%.

The pooled mean HCV prevalence for special clinical populations was 4.6% (95% CI: 3.2–6.1%). There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), with an I2 of 96.9% (95% CI: 96.5–97.3%). The prediction interval was 0.0–21.6%. For the subpopulations of populations with liver-related conditions and other special clinical populations, the pooled means were 7.5% and 2.7%, respectively.

The forest plots for the HCV prevalence meta-analyses can be found in Figs S3 and S4.

Sensitivity analysis

After excluding blood donor data, the national population-level HCV prevalence was estimated at 0.3% (95% CI: 0.2–0.5%). There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (p < 0.0001), with an I2 of 76.3% (95% CI: 67.5–81.7%). The prediction interval was 0.0–1.3%. The forest plot for this sensitivity analysis can be found in Fig. S5.

HCV RNA prevalence

Our search identified a total of 55 HCV RNA measures. The details of each of these measures can be found in Table S4. These were reported either among HCV antibody positive individuals, or as a proportion of the entire sample. HCV RNA prevalence among HCV antibody positive individuals ranged from 0% to 89.3%, with a median of 61.9%. HCV RNA prevalence as a proportion of the entire sample ranged from 0% to 60.0%, with a median of 8.6%. HCV RNA prevalence as a proportion of the entire sample was high in several populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures.

Risk factors for HCV infection

A number of studies assessed risk factors for HCV exposure using multivariable regression analyses. Risk factors most commonly reported included history and duration of incarceration and multiple incarcerations50–62, history and duration of intravenous drug use50,51,54,57,58,60–67, history of sharing a needle or syringe55,57,62,68,69, history of tattooing50–52,61,70,71, history of sharing razors67, multiple sex partners57,58,66,67,69,70,72, being a man who have sex with men54,62,68,73, history of surgery70,73, history of blood transfusion56,60,73, and history of hemodialysis74.

HCV genotypes

HCV genotype data was identified in 66 studies including a total of 24,029 HCV RNA positive individuals. Of these, 895 individuals had an undetermined genotype and were therefore excluded from further analysis. The vast majority of individuals were infected by a single genotype, with only 2.9% being infected by multiple genotypes. The proportion of infections for each HCV genotype was highest in genotype 1 (58.2%), followed by genotype 3 (39.0%), genotypes 2 (1.7%), and genotype 4 (1.0%).

The pooled mean proportion for genotype 1 was 56.3% (95% CI: 52.9–59.6%), genotype 3 was 38.8% (95% CI: 35.7–41.9%), genotype 2 was 0.4% (95% CI: 0.0–1.0%), and genotype 4 was 0.0% (95% CI: 0.0–0.1%).

Genotype 1 was more common among populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures than genotype 3. Meanwhile, genotype 3 was more common among PWID than genotype 1. Within genotype 1, subtype 1a and subtype 1b were isolated (where subtype information was available) from 79.5% and 20.5% of individuals, respectively.

Quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment are summarized in Table 5. The majority of HCV incidence measures (60%) were based on samples with >100 participants, and therefore were classified as having high precision. Incidence studies were based on convenience sampling from clinical facilities, and 60% had a response rate >80%. All incidence measures were based on biological assays.

Table 5.

Summary of precision and risk of bias (ROB) assessment for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) incidence and prevalence measures extracted from eligible reports.

| Quality assessment | HCV incidence | HCV prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Precision of estimates | ||||

| High precision | 3 | 60.0 | 312 | 77.4 |

| Low precision | 2 | 40.0 | 79 | 19.6 |

| Uncleara | 12 | 3.0 | ||

| Risk of bias quality domains | ||||

| HCV ascertainment | ||||

| Low risk of bias | 5 | 100 | 402 | 100 |

| High risk of bias | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sampling methodology | ||||

| Low risk of bias | 0 | 0 | 48 | 11.9 |

| High risk of bias | 5 | 100 | 350 | 87.1 |

| Unclear | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Response rate | ||||

| Low risk of bias | 3 | 60.0 | 370 | 92.0 |

| High risk of bias | 2 | 40.0 | 10 | 2.5 |

| Uncleara | 0 | 0 | 22 | 5.5 |

| Total studies where risk of bias assessment was possible | 5 | 100 | 402 | 99.8 |

| Unknown b | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | |

| Total studies | 5 | 100 | 403 | 100 |

| Summary of risk of bias assessment for HCV prevalence measures | n | % | ||

| Low risk of bias | ||||

| In at least one quality domain | 402 | 100 | ||

| In at least two quality domains | 371 | 92.3 | ||

| In all three quality domains | 47 | 11.7 | ||

| High risk of bias | ||||

| In at least one quality domain | 350 | 87.1 | ||

| In at least two quality domains | 10 | 2.5 | ||

| In all three quality domains | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total studies where risk of bias assessment was possible | 402 | 99.8 | ||

| Total studies | 403 | 100 | ||

aStudies with missing information for any of the domains were classified as having unclear risk of bias for that specific domain.

bStudies extracted through country-level routine reporting with limited description of the sample (not permitting the conduct of risk of bias assessment) were classified as being of unknown quality.

The majority of HCV prevalence measures (77.4%) were based on samples with >100 participants, and therefore were classified as having high precision. Of the 403 prevalence measures, ROB assessment was possible for 402 measures.

All HCV prevalence measures were based on biological assays. In 25.0% of measures, information on the exact biological assay was missing. Approximately one third of the samples underwent secondary confirmatory testing, with the majority using the more sensitive and specific recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA). Among studies where information was available on assay generation, the majority (71.2%) used the more recent, sensitive, and specific 3rd generation Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests, and 26.9% used 2nd generation ELISA. The majority of samples (82.6%) were drawn using non-probability based sampling. Response rate was high in 92.0% of studies.

In summary, HCV prevalence measures were of reasonable quality. All studies had a low ROB in at least one quality domain, 92.3% had a low ROB in at least two of the three quality domains, and 11.7% had a low ROB in all three quality domains. Only 2.5% of studies had a high ROB in two of the three quality domains, and no study had a high ROB in all three quality domains.

Meta-regressions and sources of heterogeneity

The results of our meta-regression models can be found in Table 6. The univariable meta-regression analyses identified population, study site, sample size, and year of data collection as significant predictors (with p < 0.1), and therefore eligible for inclusion in the final multivariable meta-regression model. Sampling methodology used (probability-based or nonprobability-based) was not associated with HCV prevalence (p > 0.1). In the final multivariable meta-regression analysis, all variables remained statistically significant (p < 0.05) with the exception of healthcare setting and unspecified study site. The final multivariable model explained 71.7% of the variability in HCV prevalence. Of note, the model indicated a statistically significant declining trend in HCV prevalence in Iran—year of data collection had an AOR of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91–0.96).

Table 6.

Univariable and multivariable meta-regression models for the mean HCV prevalence among populations in Iran.

| Number of studies | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysisa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Population classification | General population (low risk) | 122 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| PWID | 56 | 269.41 (175.01–414.72) | 0.000 | 88.80 (52.30–150.75) | 0.000 | |

| HIV patients | 25 | 273.98 (152.38–492.64) | 0.000 | 135.48 (72.30–253.87) | 0.000 | |

| Populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures | 127 | 48.08 (34.26–67.46) | 0.000 | 39.33 (25.69–60.20) | 0.000 | |

| Populations at intermediate risk | 70 | 10.10 (6.76–15.10) | 0.000 | 4.36 (2.74–6.94) | 0.000 | |

| Populations with liver-related conditions | 28 | 16.34 (9.34–28.61) | 0.000 | 10.24 (5.65–18.55) | 0.000 | |

| Other special clinical populations | 44 | 7.22 (4.51–11.55) | 0.000 | 6.01 (3.61–10.02) | 0.000 | |

| Study site | Community | 42 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Blood bank | 73 | 0.31 (0.15–0.64) | 0.002 | 0.45 (0.7–0.77) | 0.003 | |

| Prison | 44 | 28.12 (12.6–62.71) | 0.000 | 3.66 (2.05–6.52) | 0.000 | |

| Rehab/Drop-in-center | 35 | 48.49 (20.71–113.56) | 0.000 | 2.26 (1.19–4.33) | 0.013 | |

| Healthcare setting | 256 | 5.72 (3.08–10.62) | 0.000 | 0.64 (0.40–1.02) | 0.063 | |

| Unspecified | 22 | 3.74 (1.41–9.96) | 0.008 | 1.11 (0.56–2.18) | 0.766 | |

| Sampling methodology | Probability-based | 52 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Nonprobability-based | 390 | 1.7 (0.88–3.46) | 0.114 | — | — | |

| Unspecified | 30 | 1.81 (0.62–5.26) | 0.274 | — | — | |

| Sampling size | <100 | 144 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| ≥100 | 328 | 0.28 (0.18–0.44) | 0.000 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | 0.010 | |

| Year of data collection | 472 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 0.032 | 0.93 (0.91–0.96) | 0.000 | |

| Year of publication | 472 | 1.00 (0.91–1.02) | 0.150 | — | — | |

aThe adjusted R-square for the full model was 71.74%. Abbreviations: OR= Odds ratio; AOR= Adjusted odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval; PWID = People who inject drugs.

Discussion

We presented a comprehensive systematic review and synthesis of HCV epidemiology in Iran. The pooled mean HCV prevalence in the general population was estimated at only 0.3%, on the lower side of the levels observed in other MENA countries7,9,21–25,27 and globally75–77. Despite this low prevalence in the general population, high prevalence was found among PWID and populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures. These findings suggest that most ongoing HCV transmission in Iran is driven by injecting drug use and specific healthcare-related exposures. Genotypes 1 and 3 were the most frequently circulating strains. Of note, HCV prevalence in Iran is on a declining trend (Table 6).

Our estimate for the general population is slightly lower than an estimate provided for the whole adult population as part of a global estimation using a different methodology—0.3% in our study versus 0.5% in Gower et al.78. The difference may be explained by the fact that our estimate is strictly for the general (normally healthy) population. Moreover, our estimate is a pooled estimate of 122 studies as opposed to Gower’s et al. estimate which was based on five studies78. Inclusion of blood donor studies in our estimation did not explain the difference—our sensitivity analysis showed that estimated HCV prevalence in the general population was invariable with exclusion of blood donors (Fig. S5).

Iran has one of the highest population proportion of current PWID in the adult population (0.43%) in MENA, with an estimate of 185,000 current PWID16,79. Our synthesis indicated that injecting drug use was one of the most commonly reported risk factors for HCV infection, and that the pooled mean HCV prevalence among PWID was 52.2% (Table 4). These results suggest that injecting drug use is a main driver, if not the main driver, of HCV incidence in this country (Table 6). The regional context of Iran and the drug trafficking routes21,80,81, support an environment of active injection and a major role for PWID in HCV transmission. In this regard, HCV epidemiology in Iran appears to resemble that in developed countries, such as in the United States of America (USA), where most HCV incidence is attributed to drug injection17,82,83. Of note, we identified high HCV prevalence even among drug users where the route of drug use was not specified or excluded drug injection. This may suggest under-reporting of drug injection among those who report just drug use, or past drug injection among them before shifting to other forms of drug use.

Having said so, the estimated low HCV prevalence in the general population of only 0.3% apparently contradicts with a large PWID population in Iran. In the USA, it is estimated that the population proportion of current PWID is 0.3%84, and that of lifetime PWID is 2.6%84, compared to 0.43% for current PWID in Iran16. HCV prevalence among PWID in the USA is just over 50%85, therefore comparable with the pooled estimate of 52.2% for PWID in Iran (Table 4). HCV prevalence in the wider adult population in the USA is estimated at 1.0%86, much higher than the pooled estimate for HCV prevalence in the general population in Iran (0.3%). This discrepancy may be explained by an over-estimated current PWID population in Iran, very recent trend of drug injection with relatively small lifetime PWID population, or that the estimated HCV prevalence in the general population considerably underestimates the actual HCV prevalence in the whole adult population in Iran.

Our synthesis suggests that prisons have been a major setting for HCV transmission in Iran (Table 6). With nearly 60% of prisoners being incarcerated for drug-related offences81, high reported injecting risk behaviors in prisons16,28, and the high HCV prevalence among prisoners (Tables 3 and S2), prisons should be a main focus of HCV prevention and treatment efforts. Iran has made major and internationally-recognized strides in establishing harm reduction services for PWID including in prisons16,33,87–90, but further scale-up of these services in all prisons is warranted.

High HCV prevalence was found in populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures such as hemodialysis, hemophilia, and thalassemia patients, though with geographical variation (Tables 3 and 6). This finding, along with the higher HCV prevalence generally among clinical populations (Table S3), suggests that healthcare is also a main driver of HCV transmission, though less so than in most other MENA countries7,9,21–25,27. The quality of healthcare and application of stringent protocols for infection control appear also to vary by setting within Iran. Overall, however, Iran seems to have made major progress in reducing HCV exposures through healthcare, which may explain the declining trend in HCV prevalence (Table 6)91–93. For example, HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients was reported in one study to have declined from 14.4% in 1999 to 4.5% in 200694.

HCV genotype 1 was the dominant circulating strain in Iran (56% of infections), followed by genotype 3 (39% of infections). This shows similarity to the pattern observed in multiple countries globally95. Nevertheless, this genotype distribution differs substantially from that found in most other MENA countries29. Several recent studies have also indicated an increasing presence of genotype 396,97. This shift may be due to the fact that injecting drug use is a major driver of HCV incidence29,98 (Table 6), or the fact that this is a sub-regional pattern—genotype 3 is the main circulating strain in neighboring Pakistan29.

Our meta-analyses confirmed high heterogeneity in estimated effect sizes (Table 4). This was expected, due to differences between studies in variables such as risk population, study site, sampling methodology, sample size, and year of data collection, among others. Our meta-regressions identified several sources of heterogeneity in HCV prevalence studies in Iran. As expected, large differences in HCV prevalence by risk population were observed (Table 6). A small-study effect was also observed, with small studies reporting higher HCV prevalence. Importantly, a time trend was also observed with a declining HCV prevalence with time.

Our study is limited by the quality of available studies, as well as their representativeness of the different risk populations. High heterogeneity in prevalence measures were identified in all meta-analyses for all risk populations (Table 4). Meta-regression analyses were performed to identify the sources of heterogeneity, and while the final multivariable regression model accounted for 71.7% of observed heterogeneity, there are variables that we are unable to assess, such as “hidden” selection bias in recruitment.

Another limitation is the absence of reporting of the specific used biological assay in 25.0% of studies. The majority of included studies were based on convenience sampling. Although this is presumed a limitation, the meta-regression analyses did not identify sampling methodology as a statistically significant source of heterogeneity in HCV prevalence (p = 0.114; Table 6).

Despite these limitations, the main strength of our study is that we identified a very large number of studies, in fact the largest of all MENA countries7,9,21–25,27, that covered all risk populations and that allowed us to have such a comprehensive synthesis of HCV epidemiology.

Conclusions

HCV prevalence in the wider population in Iran appears to be considerably below 1%—on the lower range compared to HCV prevalence in other MENA countries and globally. However, high HCV prevalence was found among PWID and populations at high risk of healthcare-related exposures. Most ongoing HCV transmission appears to be driven by injecting drug use and specific healthcare-related exposures. Genotypes 1 and 3 were the most frequently circulating strains.

There are still gaps in our understanding of HCV epidemiology in this country. Conduct of a nationally-representative population-based survey is strongly recommended to provide a better estimate of HCV prevalence in the whole population, delineate the spatial variability in prevalence, identify specific modes of exposure, and assess HCV knowledge and attitudes, as has been recently conducted in Egypt10,99–103 and Pakistan6,15,104.

Our study informs planning of health service provision, development of policy guidelines, and implementation of HCV prevention and treatment programming to reduce HCV transmission and decrease the burden of its associated diseases. Our findings suggest the need of a targeted approach to HCV control based on settings of exposure. Iran has established internationally-celebrated harm reduction services for PWID16,87–90,105, but these services need to be accessible to all PWID across the country, as well as in relevant settings, such as prisons. Further focus on infection control in healthcare facilities is also warranted, such as the adoption of the new WHO guidelines for the use of safety-engineered syringes106,107.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karima Chaabna for providing methodological expertise for the conduct of this study. This publication was made possible by NPRP grant number 9–040–3–008 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The findings achieved herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. The authors are also grateful for support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar.

Author Contributions

S.M. conducted the systematic review of the literature, data retrieval, extraction, analysis, and wrote the first draft of the paper. V.A. contributed to the systematic review of the literature, data retrieval, and extraction. L.J.A. conceived and led the design of the study, analyses, and drafting of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-18296-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alavian S, Fallahian F. Epidemiology of Hepatitis C in Iran and the World. Shiraz E Medical Journal. 2009;10:162–172. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler M, Goubau P, Nevens F, Van Vlierberghe H. Hepatitis C virus: the burden of the disease. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica. 2001;65:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanaway JD, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2016;388:10–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global Hepatitis Report, http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/ (2017).