Abstract

Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima is a Chinese herbal medicine used for the treatment of gynecological diseases. An HPLC/DAD/ESI-MSn method was established for the rapid separation and characterization of bioactive flavonoids in M. nitida var. hirsutissima. A total of 32 flavonoids were detected, of which 14 compounds were unambiguously characterized by comparing their retention time, UV, and MS spectra with those of the reference standards, and the others were tentatively identified based on their tandem mass spectrometry fragmentation data obtained in the negative ionization mode on line. Nineteen of these compounds characterized were reported from this plant for the first time.

Keywords: HPLC/DAD/ESI-MSn, Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima, Mass spectrometry, Flavonoids

1. Introduction

Millettia nitida Benth. var. hirsutissima Z. Wei (Fengcheng Jixueteng in Chinese) is a perennial herb distributed in Jiangxi and Fujian provinces of Southeast China [1]. In Chinese folk medicine, it is used to treat dysmenorrhea, irregular menstruation, rheumatic pain, aching pain, as well as paralysis [2]. Pharmacological studies have revealed that M. nitida var. hirsutissima could recover liver function by promoting the DNA replication of hepatocytes [3]. An extract of this herb also exhibited obvious free radical scavenging activities [4]. Flavonoid components were commonly regarded as the bioactive constituents of M. nitida var. hirsutissima [5], [6]. In our previous work, 21 flavonoids were isolated from M. nitida var. hirsutissima and their structures were elucidated by MS, 1H –NMR and 13C –NMR [7], [8], [9], [10]. Few reports are available on the global analysis of chemical constituents of this plant.

In this paper, a fast and reliable HPLC/DAD/ESI-MSn method was established for the qualitative analysis of Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima. A total of 32 flavonoids were characterized, including 10 isoflavones, 3 chalcones, 5 flavanones, 1 pterocarpan, 2 flavans and 11 flavonoid glycosides. Among them, 19 compounds were reported from M. nitida var. hirsutissima for the first time.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and materials

The reference standards were isolated by the authors. Their structures were fully characterized by NMR and MS spectroscopy [7], [8], [9], [10]. The dried stems of M. nitida var. hirsutissima were collected in Fengcheng, Jiangxi province of China, in May 2003, and were identified by Professor Hubiao Chen. A voucher specimen was deposited in the Department of Natural Medicines, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Peking University.

HPLC grade acetonitrile, formic acid (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) were used, and ultra-pure water was prepared using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, MA, USA). Methanol, petroleum ether (60–90 °C) and ethyl acetate (AR grade) for sample extraction were purchased from Beijing Chemical Corporation (Beijing, China).

2.2. Apparatus and analytical conditions

The HPLC analyses were performed on an Agilent series 1100 HPLC instrument (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a quaternary pump, a diode-array detector, an autosampler and a column compartment. Samples were separated on an Agilent Zorbax Extend-C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm×250 mm). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (A) and water containing 0.03% (v/v) formic acid (B). A gradient elution program was used as follows: 0–13 min, 10–18% A; 13–18 min, 18–20% A; 18–35 min, 20–25% A; 35–42 min, 25–28% A; 42–60 min, 28–45% A; 60–65 min, 45–57% A; 65–70 min, 57–100% A; 70–75 min, 100% A. The mobile phase flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. Spectral data were recorded using diode-array detector over the wavelength range 190–600 nm and the chromatogram was extracted at 280 nm. The column temperature was set at 40 °C.

For LC/MS analysis, a Finnigan LCQ Advantage ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA, USA) was connected to the Agilent 1100 HPLC instrument via an ESI interface. The LC effluent was introduced into the ESI source in a post-column splitting ratio of 5:1. Ultrahigh-purity helium (He) was used as the collision gas and high purity nitrogen (N2) as the nebulizing gas. The mass spectrometer was monitored in the negative mode. The optimized detection parameters were as follows: ion spray voltage, 4.5 kV; sheath gas (N2), 50 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas (N2), 10 units; capillary temperature, 330 °C; capillary voltage, −60 V; tube lens offset voltage, −15 V. A source fragmentation voltage of 25 V was applied. For tandem mass spectrometry analysis, the collision energy for CID (collision induced dissociation) was adjusted to 35% of maximum, and the isolation width of precursor ions was 2.0 Th.

2.3. Sample preparation

The herbal materials were ground into a fine powder (through a sieve of 100 meshes). An aliquot of 8 g of M. nitida var. hirsutissima, accurately weighed, was extracted for 30 min with 80 mL of methanol on an ultrasonic water bath (30 °C), and the extract was then filtered. The solution was evaporated to dryness in a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at 40 °C, and was then suspended in 10 mL of water. The resulting solution was extracted by 10 mL petroleum ether and 10 mL ethyl acetate consecutively. The ethyl acetate extract was dried and dissolved in 1.5 mL of acetonitrile. The solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm micropore membrane (Nylon 66; JinTeng, Tianjin of China) prior to LC/MS analysis. A 10-μL aliquot was introduced into the LC/MS instrument for analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optimization of HPLC conditions

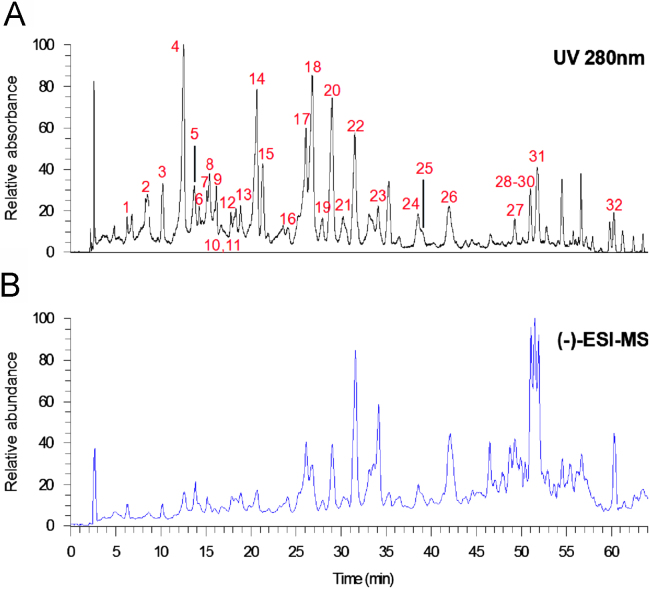

In order to obtain desirable HPLC chromatograms, the procedure of sample preparation was optimized in terms of the extraction solvent, the solvent for extraction of flavonoids from the crude extract and the ratio of raw material to liquid. First of all, three different extraction solvents, including 50% (v/v in water), 70% and 100% aqueous methanol, were selected as the extraction solvents. No significant difference was observed between the obtained chromatograms, and pure methanol was applied as the extraction solvent finally. Secondly, experiments showed that lipophilic components in the methanol extract could be removed by extracting with petroleum ether, and ethyl acetate enabled the accumulation of flavonoids with satisfactory HPLC baseline. Therefore, the crude methanol extract was suspended in water, and then successively extracted with petroleum ether and ethyl acetate, respectively. The ethyl acetate extract was used for LC/MS analysis. Thirdly, the sample concentration was adjusted to 8 g crude drug per 1.5 mL so as to detect as many compounds as possible, but not to result in ESI source contamination. Different columns (Zorbax SB-C18, Zorbax Extend-C18, YMC ODS-A and Waters Atlantis dC18) were tested for the separation of the sample. By comparison, Zorbax Extend-C18 column gave the best chromatographic resolution among the four columns. For the mobile phase, 0.03% (v/v) formic acid was added to improve the mass spectrometry ionization efficiency and enable symmetric peak shapes. The detection wavelength was set at 280 nm, at which most flavonoid components can be detected sensitively. The HPLC chromatogram and LC/MS total ion current of M. nitida var. hirsutissima are given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

HPLC and ESI-MS chromatograms of Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima. (A) HPLC chromatogram at 280 nm; (B) ESI-MS chromatogram in the negative mode.

3.2. Optimization of mass spectrometry conditions

Both the positive and negative ion modes were tested for MS analysis. Most flavonoids showed much cleaner mass spectral background and higher sensitivity in the negative mode than those obtained in the positive mode [11]. In the positive mode, flavonoids usually gave molecular adduct ions, such as [M+H]+, [M+Na]+, together with various fragment ions in the full scan mode when no collision energy was applied, while in the negative mode most flavonoids yielded predominant [M−H]− ions. Therefore, the negative detection was selected for LC/MS analysis. The source fragmentation voltage was set at 25 V, for it effectively reduced adducted ions ([M−H+HCOOH]− and [2M−H]−), and enhanced molecular ions ([M−H]−) for majority of analytes. For LC/MS analysis, a data-dependent program was utilized for tandem mass spectrometry data acquisition. In this program, [M−H]− ions detected in the full scan mode were selected for MS2 analysis. The two most abundant fragment ions in the MS2 spectra were then selected as parent ions to trigger MS3 fragmentation. The tandem mass data were analyzed to elucidate the chemical structures of unknown flavonoids.

3.3. Rationale for the characterization of flavonoids

Known compounds in the herbal extract were identified by comparing with reference standards according to the retention time and MSn spectra. The unknown compounds were characterized by analyzing their fragmentation behaviors in MS2 and MS3 spectra, their UV spectra, and by referring to previous reports. A total of 32 flavonoids were characterized (Table 1). Among them, fourteen compounds, 1, 5, 7, 9, 13, 16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30 and 32, were identified by comparing with reference standards, and the other compounds were tentatively identified. In total, 19 compounds were reported from M. nitida var. hirsutissima for the first time. The compounds with relatively confirmed structures are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Compounds identified from Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima.

| No. | Retention time (min) | UVmax(nm) | [M−H]− (m/z) | HPLC/ESI-MSnm/z(% base peak) | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 5.29 | 212 | 289 | 289→245(100), 205(30), 227(1), 203(1), 179(10), 161(1), 137(1) | (+)-Catechin |

| 2 | 8.51 | 463 | 463→301(100), 343(1), 313(1), 255(1) | Quercetin-O-hexoside | |

| 301→257(100), 259(70), 283(35), 273(25), 271(5), 151(5) | |||||

| 3 | 10.29 | 463 | 463→301(100), 343(1), 255(1), 191(1) | Quercetin-O-hexoside | |

| 301→257(100), 259(70), 283(35), 273(25), 271(5), 151(15), 135(5) | |||||

| 4 | 12.54 | 230, 278 | 287 | 287→269(100), 259(15), 225(1)163(15), 109(1), 135(1) | 3, 7, 3′, 4″-Tetrahydroxyflavanone |

| 269→225(100), 241(20), 201(1), 163(20) | |||||

| 5a | 12.57 | 431 | 431→311(100), 283(4), 341(4) | Isovitexin | |

| 6 | 14.36 | 230, 268 | 445 | 445→283(100) | Calycosin-O-hexoside |

| 283→268(100), 255(1), 239(1), 211(1) | |||||

| 7ab | 15.16 | 577 | 577→269(100), 503(3) | Sphaerobioside [10] | |

| 269→269(100), 240(20) | |||||

| 8 | 15.45 | 226, 268 | 303 | 303→285(100), 193(1) | Dihydroquercetin |

| 285→241(100), 175(40), 217(20), 213(1), 243(15), 177(1) | |||||

| 9a | 16.06 | 431 | 431→268(100), 311(10), 341(1), 371, (1), 223(1) | Genistin | |

| 268→267(100), 240(60), 224(40), 226(20), 211(20) | |||||

| 10 | 16.79 | 299 | 299→284(100), 299(1) | Isomer of 3′-O-methylorobol | |

| 284→284(100), 135(10), 256(20)241(10), 212(20), 228(20), 200(20), 148(20), 136(5) | |||||

| 11 | 17.28 | 579 | 579→271(100), 269(10), 313(5), 417(10), 519(1), 533(1) | Trihydroxyflavanone-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside | |

| 271→151(100), 177(80) | |||||

| 12 | 17.87 | 461 | 461→446(100), 298(80), 371(1), 341(50), 283(20), 269(1), 164(1) | Gliricidin-O-hexoside | |

| 446→283(100), 255(15), 211(1) | |||||

| 13a | 18.93 | 299 | 299→284(100), 299(50), 271(15), 256(10), 212(1), 175(1) | Gliricidin | |

| 284→256(100), 227(20), 212(5), 200(5) | |||||

| 14 | 20.72 | 230, 278 | 271 | 271→135(100), 153(60), 253(30), 243(1), 183(1), 91(1) | 7, 3′, 4′-Trihydroxyflavanone |

| 15 | 21.16 | 226, 262 | 447 | 447→285(100) | Tetrahydroxyisoflavone-O-hexoside |

| 285→285(100), 257(20), 240(5), 229(20), 212(10), 199(17), 176(15) | |||||

| 16ab | 23.61 | 561 | 561→267(100), 545(1), 532(1), 252(1)267→252(100) | Formononetin-7-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1, 6)–O- D-glucopyranoside [7] | |

| 17ab | 26.18 | 262 | 267 | 267→252(100), 267(30) | Formononetin [10] |

| 252→251(100), 223(60), 208(40), 195(10), 168(1), 132(10) | |||||

| 18b | 26.9 | 226, 278 | 269 | 269→269(100), 225(40), 241(30), 251(10), 213(1), 197(10), 133(20) | Genistein [9] |

| 19ab | 27.93 | 255 | 255→255(1), 153(80), 135(100), 119(20), 91(5) | Liquiritigenin [8] | |

| 20 | 29.24 | 230, 288 | 283 | 283→268(100), 283(10), 240(5) | Isomer of calycosin |

| 268→240(100), 267(1)224(20), 211(30), 196(10), 184(5), 120(5), 135(5) | |||||

| 21 | 30.23 | 285 | 285→135(100), 153(80), 149(75), 270(60), 285(20), 256(5), 91(50) | 7-Methoxy-3′, 4′ –dihydroxyl flavanone | |

| 22a | 31.57 | 230, 290 | 283 | 283→268(100), 283(1), 224(1) | Calycosin |

| 268→240(100), 268(40), 224(30), 211(40), 195(15), 184(20), 135(1), 120(5), 148(1) | |||||

| 23ab | 34.14 | 577 | 577→283(100), 268(10) | Lanceolarin [10] | |

| 283→268(100), 283(10) | |||||

| 268→267(100), 240(15), 223(10) | |||||

| 24 | 38.52 | 380 | 271 | 271→253(25), 228(1), 135(100), 153(80), 109(1), 91(1) | 3, 4, 2′, 4′-Tetrahydroxychalcone |

| 153→135(100), 153(40) | |||||

| 25 | 38.91 | 260 | 283 | 283→268(100), 283(20) | Isomer of calycosin |

| 268→267(100), 240(60), 224(40), 226(20), 211(20) | |||||

| 26ab | 42.15 | 230, 264 | 299 | 299→284(100), 299(20), 271(10), 256(1) | 3′-O-Methylorobol [9] |

| 284→284(100), 267(10)256(80), 240(20), 227(30), 212(1), 148(5) | |||||

| 27 | 49.31 | 370 | 255 | 255→254(1), 213(1), 153(60), 135(100), 119(40), 91(5) | Isoliquiritigenin |

| 28 | 51.13 | 242 | 267 | 267→252(100), 267(20) | Isomer of formononetin |

| 252→252(100), 223(90), 208(40), 195(1), 132(10) | |||||

| 29a | 51.66 | 230, 282 | 297 | 297→282(100), 267(10), 253(1) 282→267(100), 281(1), 239(20) | 8-O-Methylretusin |

| 267→239(100), 223(20), 267(5), 211(1) | |||||

| 30ab | 51.73 | 226, 284 | 271 | 271→109(100), 256(70), 253(80), 227(40), 135(60) | 7, 2′-Dihydroxy-4-methoxyl isoflavan [8] |

| 31 | 51.82 | 380 | 285 | 285→135(100), 270(95), 153(60), 149(60) 243(20), 214(1), 201(1) | 3, 2′, 4′, -Trihydroxy-4-methoxychalcone |

| 32ab | 60.37 | 262 | 283 | 283→268(100), 283(10) | Maackiain [8] |

| 268→267(100), 240(60), 224(40), 212(5), 196(1), 164(1), 109(1) |

The compound was unambiguously identified by comparing with reference standards.

The compound had been reported from this plant. The reference was labeled.

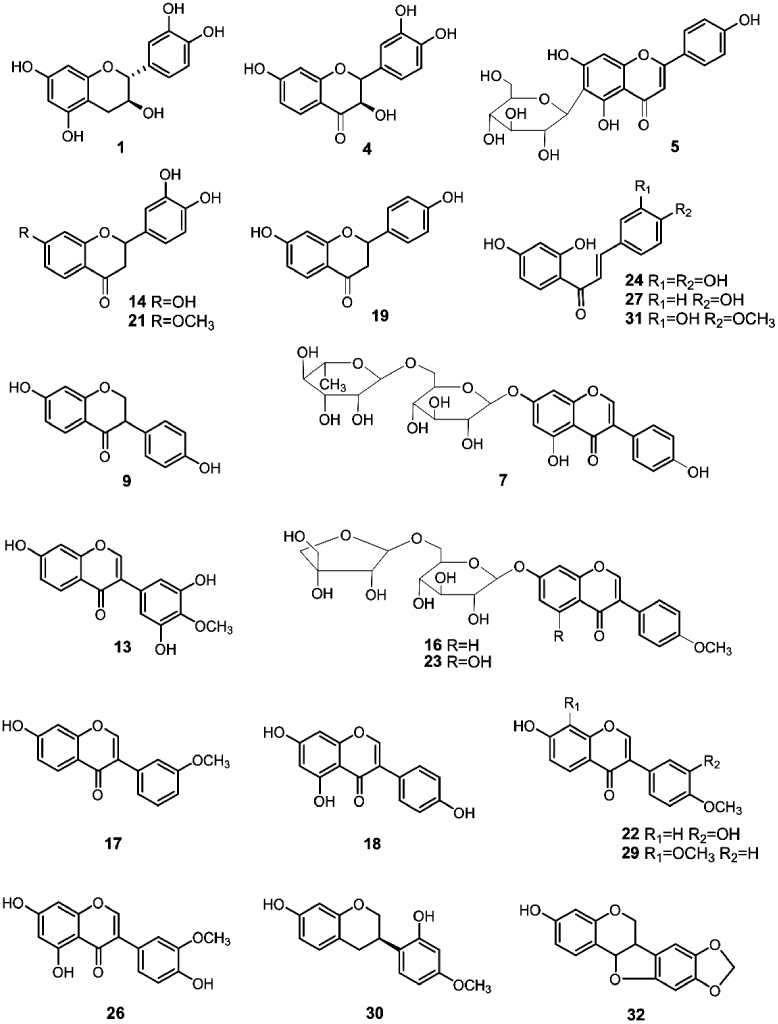

Figure 2.

Selected chemical structures of identified compounds (compounds 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31 and 32).

3.4. Identification of isoflavones (compounds 10, 13, 17, 18, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28 and 29)

Note: The nomenclature for flavonoid mass spectrometry fragmentation proposed by Hughes et al. was adopted in this paper [12].

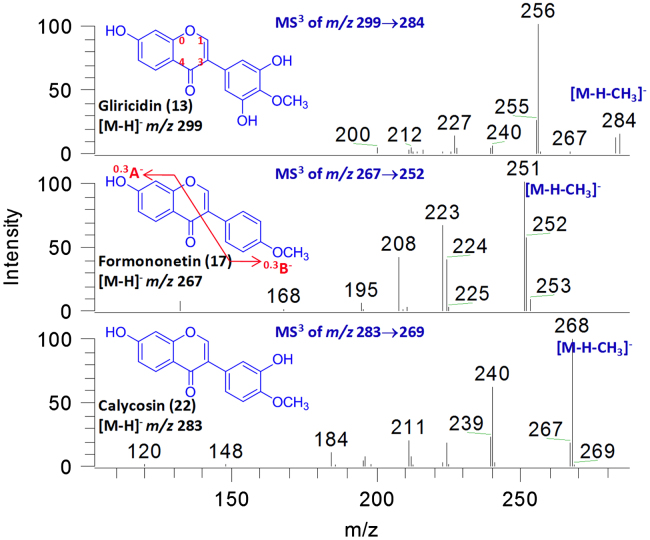

Most isoflavones showed UV absorption band at 250–270 nm, which helped to confirm them. Moreover, the tandem mass spectrometry of pure isoflavones, including calycosin, gliricidin, 3-O-methylretusin and formononetin, were investigated. Although RDA (Retro-Diels Alder) fragmentation could be observed in the mass spectra of most flavonoids, it was rarely detected in isoflavones in our study. Instead, a fragmentation at C-ring producing 0,3A− and 0,3B− ions was detected in low abundance, which was consistent with previous report [12]. We also observed that the isoflavones gave a series of regular neutral losses of 28 Da, 44 Da, 56 Da, 72 Da and 84 Da in the MS spectra, which could be attributed to CO, CO2, 2CO, CO+CO2 and 3×CO, respectively (Fig. 3). Similar fragment ions were observed from other isoflavones and isoflavone glycosides as well. Additionally, the MS spectra of flavones were much more complex than those of isoflavones. For instance, flavones with different hydroxylation patterns could yield ions like [M−H−C3O2]−, [M−H−C2H2O]− or [M−H−CH2O]− [13], [14]. The fragmentation pathways depended closely on the hydroxylation patterns. Unfortunately, these fragment ions were barely observed in isoflavones. For this reason, the exact locations of the hydroxyl substituents of isoflavones could not be deduced. However, the differences between the MS spectra of flavones and isoflavones, as well as the characteristic UV spectra, could serve as evidences to identify the structures of isoflavones. In this study, a total of 10 isoflavones were characterized.

Figure 3.

The MS3 spectra of calycosin, gliricidin and formononetin.

Three compounds (20, 22 and 25) in the herbal extract gave [M−H]− ion at m/z 283, and yielded similar MS/MS product ions. Compound 22 was identified as calycosin by comparing with a reference standard. MS/MS spectra of the three compounds gave m/z 268 ions ([M−H−CH3]−) as the base peak, suggesting the presence of a methoxyl group [15]. The 0,3A− ion at m/z 120 indicated the existence of a hydroxyl group on ring A. In addition, compound 20 showed similar UV spectra (λmax 230 nm, 288 nm) to 22, and was identified as calycosin isomer. Compound 25 exhibited maximum absorption at λmax 260 nm, which was in agreement with certain type of calycosin isomer (biochanin A, λmax 260 nm [9]), thus allowed its identification.

Compounds 17 and 28 both gave [M−H]− ions at m/z 267. Their MS/MS spectra gave m/z 252 ions ([M−H−CH3]−) as the base peak, suggesting the presence of a methoxyl group. The 0,3B− ions at m/z 132 indicated that the methoxyl group should be located on B ring. Compound 17 was identified as formononetin by comparing with a reference standard [10]. Compound 28 was subsequently identified as the isomer of formononetin.

Compounds 10, 13 and 26 exhibited [M–H]− ions at m/z 299. Their MS2 spectra showed a base peak at m/z 284 corresponding to neutral loss of methyl radical (CH3, 15 Da). Compounds 13 and 26 were identified as gliricidin and 3′-O-methylorobol, respectively, by comparing with reference standards. For compound 10, the 0,3A− ion at m/z 148 and the 0,3B− ion at m/z 136 indicated that ring A was substituted with two hydroxyl groups, and that ring B was substituted with one hydroxyl group and one methoxyl group. Thus, compound 10 should be an isomer of 3′-O-methylorobol, and was tentatively identified as 5, 7, 3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyl isoflavone.

Compound 18 gave [M−H]− at m/z 269. The MS/MS spectrum showed neutral losses of CO and CO2. Thus, compound 18 was tentatively identified as genistein [9]. Compound 29 gave [M−H]− ion at m/z 297. The MS/MS fragments at m/z 282 and 267 due to successive losses of 15 Da from [M−H]− indicated the presence of two methoxyl groups. Ions at m/z 267 then lost 28 Da, 44 Da and 56 Da. It was identified as 8-O-methylretusin by comparing with a reference standard. Our mass spectral data supported this structure very well.

3.5. Identification of flavanones (compounds 4, 8, 14, 19 and 21)

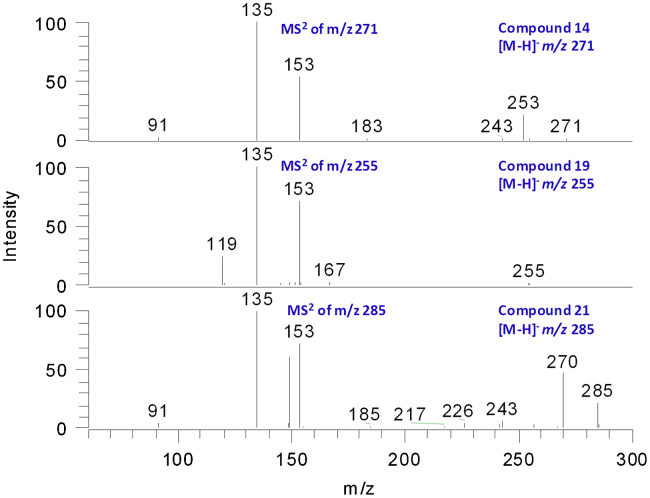

A number of flavanones had been reported from Millettia species [6]. Different from isoflavones, the CID of flavanones usually gave 1,3A− ions through RDA fragmentation as the base peak [12]. In this study, five flavanones were detected from M. nitida var. hirsutissima. Compound 19 was characterized as liquiritigenin by comparing with a reference standard. The MS/MS spectrum gave a 1,3A− ion at m/z 135 (100%) and a 1,3B− ion at m/z 119 (20%). Compound 14 gave [M−H]− ion at m/z 271. In its MS/MS spectrum, the base peak was m/z 135, which could be assigned as both 1,3A− and 1,3B− ions. This information indicated that ring A of compound 14 was substituted with only one hydroxyl group, while ring B was substituted with two hydroxyl groups. Therefore, compound 14 could be tentatively identified as 7, 3′,4′-trihydroxyflavanone. Compound 21 gave [M−H]− ion at m/z 285. The fragment ion at m/z 270 ([M−H−CH3]−) indicated the presence of a methoxyl group. A specific fragment ion m/z 149, which was 14 Da larger than the fragment ion m/z 135, was observed for compound 21. The mass difference of 14 Da should be attributed –CH3 and −H substitution, indicating that the methoxyl group should be located on ring A. Therefore, the structure of compound 21 was characterized as 7-methoxy-3′, 4′-dihydroxy flavanone. It might be noteworthy that [1,3A+H2O]− ions were observed for the above flavanones in great abundance (60–90% of base peak). How these adduct ions were formed need further investigation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The MS3 spectra of compound 14, 19 and 21.

Compounds 4 ([M−H]− m/z 287) and 8 ([M−H]− m/z 303) were also identified as flavanones. However, their MS/MS fragmentation patterns were remarkably different from the above three compounds. Particularly, [M−H−H2O]− ions were observed in the MS/MS spectra as base peak. This fragmentation could be due to the presence of a 3−OH group. Similar fragmentations were recently reported for flavanonols [16]. The [M−H]− of compound 4 yielded the fragment ion at m/z 135, which was attributed to 1,3A− and indicated the presence of one hydroxyl group on ring A. Moreover, the ion at m/z 163 corresponding to 1,2A− suggested the presence of 3−OH group. Therefore, compounds 4 was tentatively identified as 3, 7, 3′, 4′-tetrahydroxyflavanone. Compound 8 gave [M−H]− at m/z 303. The fragment ion at m/z 285, through neutral loss of 18 Da from the parent ion, indicated its flavanonol type. In MS3 spectrum of m/z 285, m/z 243, neutral loss of 42 Da (C2H2O), suggested the presence of 4′–OH, and m/z 217, lose of 68 Da (C3O2), indicated β-hydroxylation on ring A. Therefore, compound 8 was tentatively identified as dihydroquercetin.

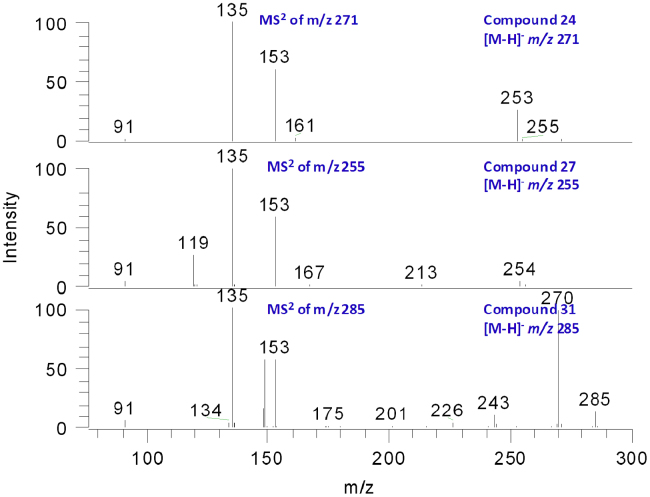

3.6. Identification of chalcones (compounds 24, 27 and 31)

Although the mass spectra of flavanones and chalcones were similar, they could be explicitly differentiated according to their UV spectra [17]. Flavanones showed maximum UV absorption at 260–280 nm, whereas chalcones at around 380 nm. Compounds 24, 27 and 31 had strong UV absorption at the bond of chalcones. All the three compounds had the same hydroxylation pattern at ring A as their MS/MS spectra gave an A− ion at m/z 135. The abnormal ion [1,3A+H2O]− appeared as well. Other fragmentation patterns were same to that of flavanones (Fig. 5). Compounds 24 and 27 were tentatively characterized as 3, 4, 2′, 4′-tetrahydroxyl chalcone and isoliquiritigenin, respectively. Compound 31 should contain a methoxyl group according to the [M−H−CH3]− ions at m/z 270, and was identified as 3.2′,4′-trihydroxy-4-methoxyl chalcone.

Figure 5.

The MS3 spectra of 24, 27 and 31.

3.7. Identification of other free flavonoids (compound 1, 30 and 32)

Compound 1 was identified as (+)-catechin by comparing with a reference standard. The MS/MS spectrum matched the reported data very well [18].

Compound 30 ([M−H]− m/z 271) was identified as 7,2′-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyl isoflavan by comparing with a reference standard. The MS/MS spectrum gave a [M−H−CH3]− ion at m/z 253 due to the presence of a methoxyl group. The ions at m/z 135 and 109 could be attributed to [1,3B−CH3]− and [B−CH3]−, respectively.

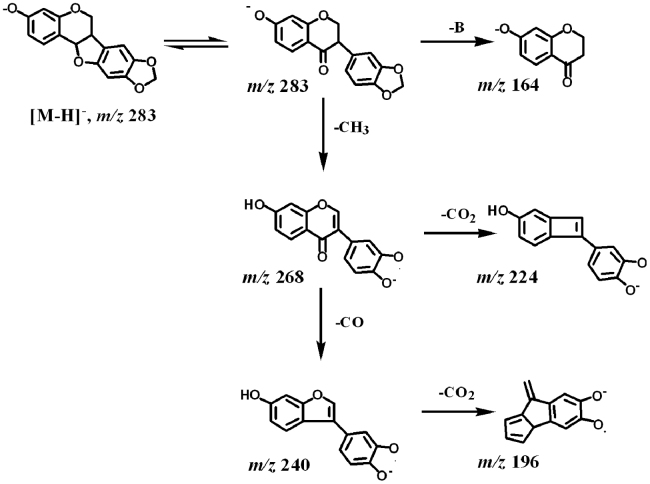

Compound 32 was the only pterocarpan detected in this study. It was identified as maackiain by comparing with a reference standard. Zhang et al. recently reported the ESI-MS/MS fragmentation of maackiain in the positive mode [16]. Here we studied its fragmentation pathway in the negative mode. Maackiain might have been converted into an isoflavanone isomer and then underwent CID fragmentations. A proposed pathway is given in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

A proposed fragmentation pathway of maackiain.

3.8. Identification of flavonoid glycosides (compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16 and 23)

A total of 11 flavonoid glycosides were identified from this plant. The tandem mass spectrometry of flavonoid glycosides has been extensively studied [19], [20]. ESI-MSn could provide abundant information on the saccharide sequence of glycosides. For O-glycosides, the elimination of 162 Da, 146 Da and 132 Da indicated hexose, deoxyhexose and pentose residues, respectively. For C-glycosides, however, the major fragmentation pathways involve cross-ring cleavages, such as 0,2X (120 Da), 0,3X (90 Da) and 0,4X (60 Da) of the saccharidic residue. These rules were used to identify unknown glycosides in this study.

Compounds 5, 7, 9, 16 and 23 were identified by comparing with reference standards. Four compounds (2, 3, 6 and 15) gave a neutral loss of 162 Da in their MS/MS spectra, indicating the presence of O-hexosyl group. Their structures were tentatively characterized as listed in Table 1.

Compounds 2 and 3 were a pair of isomers. The MS/MS spectra of their aglycones were similar. Ions at m/z 259, loss of 42 Da (C2H2O) from the base peak, suggested the presence of 4′–OH. The ion at m/z 151 attributed to 1,3A− ion, indicated two hydroxyl groups on ring A. The MS data were consistent with that of qucercetin by comparing with a reference standard. However they had different chromatographic performance depending upon the different saccharide or the glycosylation position. Therefore compounds 2 and 3 were tentatively identified as quercetin-O-hexoside.

Compound 6 gave a [M−H−162]− as m/z 283 in the MS/MS spectra. The MS3 spectrum of m/z 283 was similar to that of compound 22. Thus, it was tentatively identified as calycosin-O-hexoside.

The UV maximum absorption of compound 15 was 262 nm, suggesting its isoflavone or flavanone type. Moreover, a series of neutral loss discussed above indicated that it belonged to isoflavones. Therefore, compound 15 was tentatively identified as tetrahydroxy-isoflavone-O-hexoside.

Compound 12 gave a [M−H]− ion at m/z 461. Its MS/MS spectrum exhibited a [M−H−CH3]− as the base peak, indicating the presence of a methoxyl group. The neutral loss of 162 Da suggested the presence of a hexose. The MS3 spectrum of [M−CH3−162]− was very similar to the CID of gliricidin. Therefore, compound 12 was plausibly identified as gliricidin-O-hexoside.

Compound 11 gave a [M−H]− ion at m/z 579. Its MS/MS spectrum gave ions at m/z 417 ([M−H−162]−) and m/z 271 ([M−H−162−146]−), attributed to the elimination of a hexose and deoxyhexose residues, respectively. In addition, the deoxyhexose group should be the terminal sugar. In combination with other structural information, compound 13 was identified as trihydroxyflavanone-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside.

4. Conclusion

In summary, a simple and robust HPLC/DAD/ESI-MSn method for the qualitative analysis of chemical constituents in M. nitida var. hirsutissima was established. A total of 32 flavonoids were identified, including 10 isoflavones, 3 chalcones, 5 flavanones, a pterocarpan, 2 flavans and 11 flavonoid glycosides, and their fragmentation pathways in the negative mode were studied. Nineteen of these compounds were reported from M. nitida var. hirsutissima for the first time. The method could be employed for fast screening of target compounds, as well as for chemical identification or quality control of Millettia species. The results enriched the chemical knowledge of Millettia plants, and provided valuable ground knowledge for further pharmacological research of M. nitida var. hirsutissima.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 985 Project of Peking University Health Science Center (No. 985-2-119-121).

References

- 1.Editorial Committee of Flora of China . Science Press; Beijing: 2005. Flora of China. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui Y.J., Chen R.Y. Progress of chemistry and pharmacology of Caulis spatholobi. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2002;15(4):72–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu C.H., Wang M., Zhang W.J. Effects of Chinese herbs on DNA duplication of hepatocytes in vitro. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 1990;15(11):51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Y.Y., Zhang L.H., Cao S.W. Investigation on free radical scavenging activity of flavonoid extracts from Millettia nitida Benth. var. hirsutissima Z. Wei. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2007;19(5):741–744. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atmani D., Chaher N., Atmani D. Flavonoids in human health: from structure to biological activity. Curr. Nutr. and Food Sci. 2009;5(4):225–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M.Z., Si J.Y., Suo Z.X. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of isoflavonoids from the plants of Millettia. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2007;19(2):338–343. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng J., Zhao Y.Y., Wang B. Flavonoids from Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima. Chemical and Pharm. Bull. 2005;53(4):419–421. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng J., Liang H., Zhao Y.Y. Flavonoids from Millettia nitita var. hirsutissima. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 2006;15(3):178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng J., Xiang C., Liang H. Chemical constituents of isoflavones from vine stems of Millettia nitita var. hirsutissima. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2007;34(4):321–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang C., Cheng J., Liang H. Isoflavones from Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2009;44(2):158–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rijke E., Zappey H., Ariese F. Liquid chromatography with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of flavonoids with triple-quadrupole and ion-trap instruments. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;984(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01868-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes R.J., Croley T.R., Metcalfe C.D. A tandem mass spectrometric study of selected characteristic flavonoids. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;210(1–3):371–385. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabre N., Rustan I., Hoffmann E. Determination of flavone, flavonol and flavanone aglycones by negative ion LC–MS ion trap mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2001;12(6):707–715. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye M., Yan Y.N., Guo D.A. Characterization of phenolic compounds in the Chinese herbal drug Tu–Si–Zi by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005;19(11):1469–1484. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Y.L., Li Q.M., Heuvel H. Characterization of flavone and flavonol aglycones by collision-induced dissociation tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1997;11(12):1357–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L., Xu L., Xiao S.S. Characterization of flavonoids in the extract of Sophora flavescens Ait. by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode-array detector and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007;44(5):1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuyckens F., Claeys M. Mass spectrometry in the structural analysis of flavonoids. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;39(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/jms.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poupard P., Guyot S., Bernillon S. Characterization by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry of phloroglucinol and 4-methylcatechol oxidation products to study the reactivity of epicatechin in an apple juice model system. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1179(2):168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfender J.L., Maillard M., Marston A. Mass spectrometry of underivatized naturally occurring glycosides. Phytochem. Anal. 1992;3(5):193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 20.March R., Brodbelt J. Analysis of flavonoids: tandem mass spectrometry, computational methods, and NMR. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008;43(12):1581–1617. doi: 10.1002/jms.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]