Abstract

A rapid and sensitive liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometric (LC–MS/MS) assay method has been developed and fully validated for the simultaneous quantification of pravastatin and aspirin in human plasma. Furosemide was used as an internal standard. Analytes and the internal standard were extracted from human plasma by liquid–liquid extraction technique using methyl tertiary butyl ether. The reconstituted samples were chromatographed on a Zorbax SB-C18 column by using a mixture of 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer and acetonitrile (20:80, v/v) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The calibration curve obtained was linear (r≥0.99) over the concentration range of 0.50–600.29 ng/mL for pravastatin and 20.07–2012.00 ng/mL for aspirin. Method validation was performed as per FDA guidelines and the results met the acceptance criteria. A run time of 2.0 min for each sample made it possible to analyze more than 400 human plasma samples per day. The proposed method was found to be applicable to clinical studies.

Keywords: Pravastatin, Aspirin, Human plasma, Liquid–liquid extraction, LC–MS/MS, Pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

Management of the impaired lipid metabolism and inflammation in coronary artery patients is very important [1]. Hyperlipidemia is a major cause of atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis-associated conditions such as coronary heart disease, ischemic cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease [2]. Hyperlipidemia is characterized by elevated triglyceride levels and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, with increase in the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. Achievement of cholesterol levels in blood stream is an important objective of lipid-lowering therapy [3], [4], [5].

The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) are the most commonly used drugs in the treatment of hyperlipidemia. The statins competitively inhibit HMG-coenzyme A reductase, which is involved in the rate limiting step of cholesterol biosynthesis, thereby inhibits the mevalonate synthesis [6], [7]. Statins induce reduction in the LDL-C, which is milestone in the hyperlipedemia therapy, and lead to reduction in the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [8]. Pravastatin is a hydrophilic liver-specific inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase and is characterized one of the best among the statins due to its hydrophilic in nature [9], [10], [11]. The lipid-lowering effect is mainly due to reversible inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase activity and by inhibiting the LDL production. Pravastatin is administered orally as the sodium salt and undergoes extensive first pass metabolism in liver [12].

Aspirin is one of the most widely used anti-inflammatory agents. The anti-inflammatory activity and anti-thrombotic activity are mainly due to its reversible inhibition of the cyclooxygenase. Cyclooxygenase catalyzes the formulation of thromboxane and prostacyclin which has opposite effects on aggregation and vasodilatation. At low doses (less than 100 mg) aspirin selectively inhibits the formation of thromboxane [13]. Pravastatin in combination with aspirin reduces cardiovascular risk. The more widespread and appropriate use of both pravastatin and aspirin in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease will avoid large numbers of premature deaths [14]. A combination of buffered aspirin tablet with pravastatin sodium (Pravigard PAC, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, USA) is commercially available in the market.

To date, no method is reported for the simultaneous quantification of pravastatin and aspirin in any of the matrices. We felt that this simultaneous estimation method will help the researchers as the two drugs used in this method is available in the market with mixed combination. In this report we describe the development and validation of a simple, rapid and reproducible analytical method for the simultaneous analysis of pravastatin and aspirin concentrations in human plasma. This method provides high degree of accuracy, sensitivity and specificity by simple liquid–liquid extraction based on liquid chromatography separation and detection by electrospray-tamdem mass spectrometry. The application of this assay method to a clinical pharmacokinetic study in healthy male volunteers following oral administration of pravastatin and aspirin is described.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

The reference sample of aspirin (100.0%) was purchased form LGC Promochem, India, whereas pravastatin (97.8%) from Neucon Pharma Ltd, India. Furosemide (99.8%) used as an internal standard (IS) in this study, was obtained from Vivan Life Sciences, Mumbai, India. Water used for the LC–MS/MS analysis was prepared from Milli Q water purification system procured from Millipore (Bangalore, India). Acetonitrile and methanol were of HPLC grade and purchased from J.T Baker (Phillipsburg, USA). Analytical grade ammonium acetate and formic acid were purchased from Merck (Merck, Mumbai, India). Methyl tertiary butyl ether was purchased from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, USA). The control K2-EDTA human plasma sample was procured from Doctor's Pathological Lab (Hyderabad, India).

2.2. Instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

An HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) consisting of a Zorbax SB-C18 column (50 mm×4.6 mm, 3.5 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA ), a binary LC-20AD prominence pump, an auto sampler (SIL-HTc) and a solvent degasser (DGU-20A3) was used for the study. Aliquots of the processed samples (25 μL) were injected into the column, which was kept at 30 °C. The isocratic mobile phase, a mixture of 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer and acetonitrile (20:80, v/v), was delivered at 0.8 mL/min into the electrospray ionization chamber of the mass spectrometer. Quantitation was achieved with MS-MS detection in negative ion mode for both the analytes and the internal standard using a MDS Sciex API-4000 mass spectrometer (Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a Turboionspray ™ interface at 500 °C. The ion spray voltage was set at −4500 V. The source parameters viz. the nebulizer gas, curtain gas, auxillary gas and collision gas were set at 40, 20, 35 and 5 psi, respectively. The compound parameters viz. the declustering potential (DP), collision energy (CE), entrance potential (EP) and collision cell exit potential (CXP) were −40, −35, −10, −5 V for pravastatin, −10, −9, −10, −5 V for aspirin and −55, −25, −10, −15 V for IS. Detection of the ions was carried out in the multiple-reaction monitoring mode (MRM), by monitoring the transition pairs of m/z 423.3 precursor ion to the m/z 100.8 for pravastatin, m/z 179.0 precursor ion to the m/z 136.8 for aspirin and m/z 329.1 precursor ion to the m/z 285.0 product ion for the IS. Quadrupoles Q1 and Q3 were set on unit resolution. The analysis data obtained were processed by Analyst software™ (version 1.4.2).

2.3. Standard solutions

Primary stock solutions of pravastatin and aspirin for preparation of standard calibration curve and quality control (QC) samples were prepared from separate weighing. The stock solution of pravastatin (1 mg/mL) was prepared in methanol, whereas aspirin (1 mg/mL) was prepared in 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile and these stocks were stored at 2–8 °C; they were found to be stable for 23 day. From these stock solutions, appropriate dilutions were made using a mixture of acetonitrile and water (60:40, v/v) as a diluent, to produce working standard solutions of pravastatin and aspirin. The primary stock solution of furosemide (1 mg/mL) was prepared in methanol. A working concentration of the internal standard (1 μg/mL) solution was prepared in the diluent (acetonitrile and water, 60:40, v/v).

2.4. Preparation of calibration curve standards and quality control samples

Calibration samples were prepared by spiking 950 μL of control human plasma with the appropriate working standard solution of the each analyte (25 μL dilution of pravastatin and 25 μL of aspirin). Calibration curve standards (containing 70 μL aliquot of 150 mg/mL potassium fluoride in 1 mL of plasma) consisting of a set of nine non-zero concentrations ranging from 0.50 to 600.29 ng/mL for pravastatin and 20.07 to 2012.00 ng/mL for aspirin were prepared. Samples for the determination of precision and accuracy were prepared by spiking control human plasma in bulk with pravastatin and aspirin at appropriate concentrations and 400 μL plasma aliquots were distributed into different tubes. The QC samples prepared for each analyte were: for pravastatin – 0.50 (LLOQ), 1.50 (LQC), 96.22 (MQC1), 300.70 (MQC2) and 400.93 ng/mL (HQC); and for aspirin – 20.09 (LLOQ), 60.16 (LQC), 388.13 (MQC1), 1008.13 (MQC2) and 1600.20 ng/mL (HQC). All the samples were stored at −70±5 °C for subsequent use.

2.5. Sample processing

A 250-μL volume of the plasma sample was transferred to a 15-mL glass test tube, and to it 25 μL of working concentration of the IS (1 μg/mL) was spiked. To this 25 μL of 1% formic acid was added. After vortexing for 30 s, a 4-mL aliquot of the methyl tertiary butyl ether was added using Dispensette Organic (Brand GmbH, Wertheim, Germany) as the extraction solvent. The sample was shaken for 10 min using a reciprocating shaker (Scigenics Biotech, Chennai, India) and then centrifuged for 5 min at 4000 rpm using a Heraeus Megafuse 3SR centrifuge (Japan). The organic layer (3 mL) was transferred to a 15-mL glass test tube and evaporated at 40 °C under a stream of nitrogen. The dried extract was reconstituted with 500-μL of the mobile phase and a 25-μL aliquot was injected into the column. Sample processing was done in ice-water batch. All procedures were conducted at about 4 °C in an ice bath.

2.6. Method validation

A thorough validation of the method was carried out as per the US FDA guidelines [15]. The method was validated for selectivity, sensitivity, matrix effect, linearity, precision, accuracy, recovery, dilution integrity and stability. Selectivity of the method was assessed by analyzing eight blank (including lipemic and hemolytic plasma) human plasma matrix samples. The responses of the interfering substances or background noises at the retention time of the aspirin and pravastatin are acceptable if they are less than 20% of the response of the lowest standard curve point or LLOQ. The responses of the interfering substances or background noise at the retention time of the internal standard are acceptable if they are less than 5% of the response of the working internal standard.

Sensitivity was established from the background noise or response from six spiked LLOQ samples. The six replicates should have a precision of ≤20% and an accuracy of ±20%. Matrix effect is investigated to ensure that precision, selectivity and sensitivity are not compromised by the matrix. Matrix effect was checked with eight different lots of K2-EDTA plasma. Three replicate samples each of LQC and HQC were prepared from different lots of plasma (48 QC samples in total).

Linearity was tested for pravastatin and aspirin in the concentration range of 0.50–600.29 and 20.07–2012.00 ng/mL, respectively. For the determination of linearity, standard calibration curves containing at least 9 points (non-zero standards) were plotted and checked. In addition, blank plasma samples were also analyzed to confirm the absence of direct interferences, but these data were not used to construct the calibration curve. The acceptance limit of accuracy for each of the back-calculated concentrations is ±15% except LLOQ, where it is ±20%. For a calibration run to be accepted at least 67% of the standards, the LLOQ and ULOQ are required to meet the acceptance criterion otherwise; the calibration curve was rejected. Five replicate analyses were performed on each calibration standard. The samples were run in the order from low to high concentration.

Intra-assay precision and accuracy were determined by analyzing six replicates at five different QC levels in the same day two runs. Inter-assay precision and accuracy were determined by analyzing six replicates at five different QC levels on five different runs. The acceptance criteria includes accuracy within ±15% deviation (SD) from the nominal values, except LLOQ QC, where it should be ±20% and a precision of ≤15% relative standard deviation (RSD), except for LLOQ QC, where it should be ≤20%. Whereas batch acceptance criteria includes 67% for over all quality control samples and 50% at each level respectively.

Recovery of the analytes from the extraction procedure was determined by comparing the peak areas of the analytes in spiked plasma samples (six each of low, middle, and high QCs) with those of the analytes in samples prepared by spiking the extracted drug-free plasma samples with the same amounts of the analytes at the step immediately prior to chromatography. Similarly, recovery of the IS was determined by comparing the mean peak areas of the extracted QC samples (n=6) with those of the IS in samples prepared by spiking the extracted drug-free plasma samples with the same amounts of IS (1 μg/mL) at the step immediately prior to chromatography.

The dilution integrity exercise is performed with an aim to validate the dilution test to be carried out on higher analyte concentrations above the ULOQ during real time analysis of subject samples. Dilution integrity experiment was carried out at 1.7 times the ULOQ concentration for both the analytes. Six replicates each of 1/2 and 1/4th concentrations were prepared and their concentrations were calculated by applying the dilution factor 2 and 4.

Stability tests were conducted to evaluate the analyte stability in stock solutions and in plasma samples under different conditions. The stock solution stability at room temperature and refrigerated conditions (2–8 °C) was performed by comparing the area response of the analytes (stability samples) with the response of the sample prepared from fresh stock solution. Bench top stability in ice water bath (5 h), processed samples stability (Autosampler stability for 46 h, wet extract stability for 43 h and reinjection stability for 26 h), freeze-thaw stability in ice water bath (three cycles), long-term stability (56 day) were performed at LQC and HQC levels using six replicates at each level. Samples were considered to be stable if assay values were within the acceptable limits of accuracy (±15% SD) and precision (≤15% RSD).

2.7. Pharmacokinetic study design

A pharmacokinetic study on the drug was performed in healthy male subjects (n=12). The ethics committee approved the protocol and the volunteers provided with informed written consent. Blood samples (1 mL) were collected following oral administration of 40 mg tablet of pravastatin and 81 mg tablet of aspirin at pre-dose and 0.083, 0.167, 0.25, 0.33, 0.417, 0.5, 0.67, 0.83, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h, in K2-EDTA vacutainer collection tubes (BD, Franklin, NJ, USA) containing a 70 μL aliquot of 150 mg/mL potassium fluoride (to minimize the hydrolysis of aspirin to salicylic acid in blood) [16]. The tubes were centrifuged at 3200 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and the plasma was collected. Immediately after collection, the plasma samples were subjected to flash-freezing and stored at –70 °C till their use. Plasma samples were spiked with the IS and processed as per the extraction procedure described earlier. Along with the clinical samples, the QC samples at low, middle 1, middle 2 and high concentration levels were assayed in triplicate and were distributed among the unknown samples in the analytical run; not more than 33% of the QC samples were greater than ±15% of the nominal concentration. Plasma concentration-time profile of each analyte was analyzed by non-compartmental method using WinNonlin Version 5.1.

3. Results

3.1. Mass spectrometry

Mass parameters were tuned in negative ionization modes for the analytes. Good response was achieved in negative ionization mode. Data from the MRM mode were considered to obtain better selectivity. Deprotonated form of each analyte and IS, [M–H] – ion, was the parent ion in the Q1 spectrum and was used as the precursor ion to obtain Q3 product ion spectra. The most sensitive mass transition was monitored from m/z 423.3 to 100.8 for pravastatin, from m/z 179.0 to 136.8 for aspirin and from m/z 329.1 to 285.0 for the IS. As earlier publications have discussed the details of fragmentation patterns of pravastatin [17], aspirin [18] and the IS [19], we are not presenting the data pertaining to this.

3.2. Method development

The chromatographic conditions, especially the composition of mobile phase, were optimized through several trials to achieve good resolution and symmetric peak shapes for the analytes as well as a short run time. Separation was attempted using various combinations of acetonitrile and buffer with varying contents of each component on different columns like C8 and C18 of different makes like Chromolith, Hypersil, Hypurity advance, Zorbax, Kromasil and Intertsil. It was found that a mixture of 5 mM ammonium acetate buffer and acetonitrile (20:80, v/v) could achieve this purpose and the was finally adopted as the mobile phase. Zorbax SB-C18 column (50 mm×4.6 mm, 3.5 μm) gave a good peak shape and response even at LLOQ level for both the analytes and the IS. The retention time of pravastatin, aspirin and IS was low enough (1.12, 0.79 and 0.60 min) allowing a small run time of 2.0 min.

Liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) technique was employed for the sample preparation in this work. LLE is helpful in producing a spectroscopically clean sample and avoiding the introduction of non-volatile materials onto the column and MS system and also minimizing the experimental cost. Clean samples are essential for minimizing ion suppression and matrix effect in LC–MS/MS. Among the different solvents checked alone and in combination for their suitability, tertiary butyl methyl ether was found to be optimal, which can produce a clean chromatogram for a blank sample and yield the reproducibly recovery for the analytes from the plasma. Both pravastatin and aspirin are acidic in nature; therefore addition of formic acid improves their extraction efficiently.

A good internal standard must mimic the analyte during extraction and compensate for any analyte on the column. Isotope-labeled analyte was not available to serve as IS, so, in the initial stages of this work, several compounds were investigated to find a suitable IS and finally furosemide was found to be best for the present purpose. Furosemide was evaluated for precision and accuracy and extraction recovery of the internal standard was good and reproducible.

3.3. Selectivity and chromatography

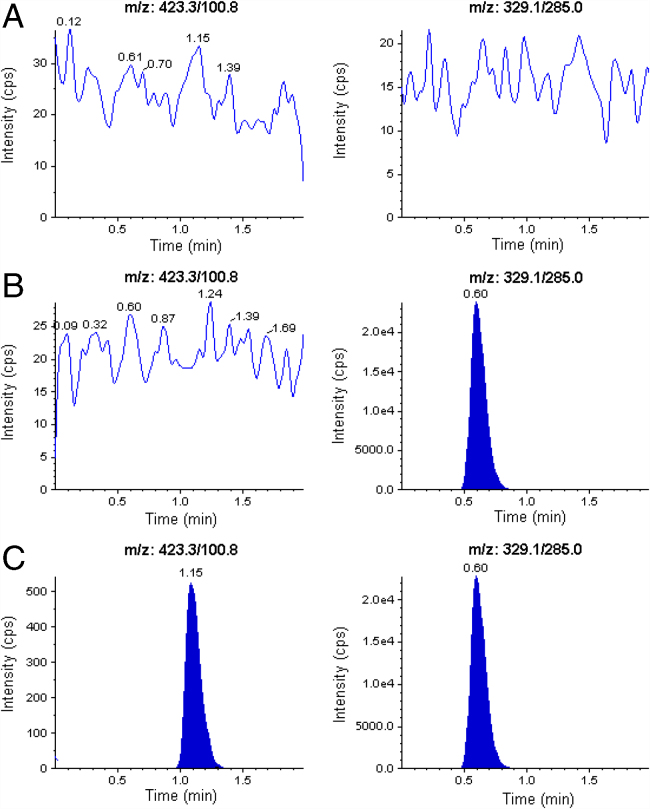

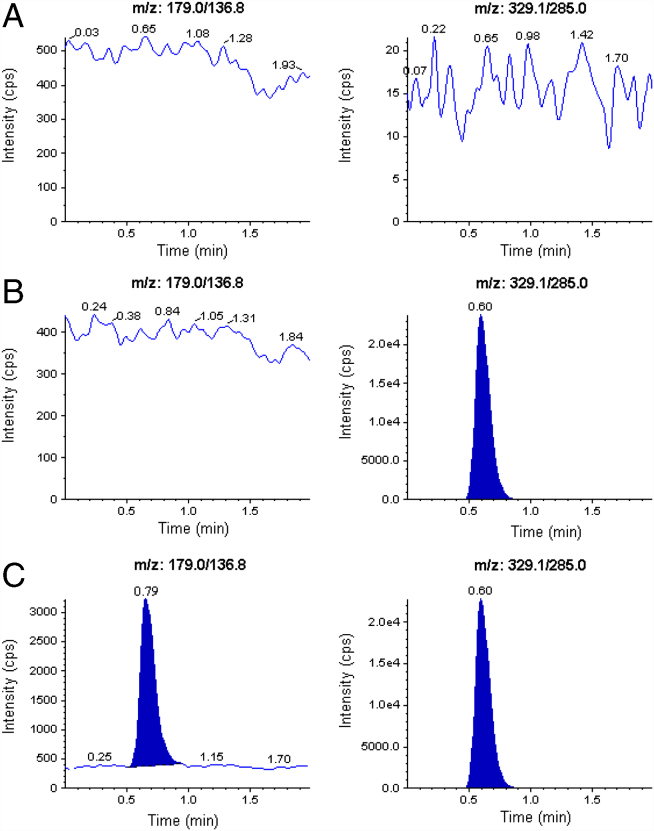

The degree of interference by endogenous plasma constituents with the analytes and the IS was assessed by inspection of chromatograms derived from processed blank plasma sample. As shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, no significant direct interference in the blank plasma traces was observed from endogenous substances in drug-free plasma at the retention time of the analytes and the IS.

Figure 1.

Typical MRM chromatograms of pravastatin (left panel) and the IS (right panel) in (A) human blank plasma and (B) human plasma spiked with IS (C) a LLOQ sample along with IS.

Figure 2.

Typical MRM chromatograms of aspirin (left panel) and the IS (right panel) in (A) human blank plasma and (B) human plasma spiked with IS (C) a LLOQ sample along with IS.

3.4. Sensitivity

The lowest limit of reliable quantification for the analytes was set at the concentration of the LLOQ. The precision and accuracy at LLOQ concentration were found to be 5.16% and 94.25% for pravastatin, 7.49% and 93.90% for aspirin.

3.5. Matrix effect

No significant matrix effect was observed in all the eight batches of human plasma for the analytes at LQC and HQC concentrations. The precision and accuracy for pravastatin at LQC concentration were found to be 2.96% and 96.95%, and at HQC level they were 6.39% and 93.08%, respectively. Similarly, the precision and accuracy for aspirin at LQC concentration were found to be 3.67% and 97.22% and at HQC level they were 6.32% and 101.02%, respectively.

3.6. Linearity

Nine-point calibration curve was found to be linear over the concentration range of 0.50–600.29 ng/mL for pravastatin and 20.07–2012.00 ng/mL for aspirin. After comparing the two weighting models (1/x and 1/x2), a regression equation with a weighting factor of 1/x2 of the drug to the IS concentration was found to produce the best fit for the concentration-detector response relationship for both the analytes in human plasma. The mean correlation coefficient of the weighted calibration curves generated during the validation was 0.99.

3.7. Precision and accuracy

Accuracy and precision data for intra- and inter-day plasma samples for pravastatin and aspirin are presented in Table 1. The assay values on both the occasions (intra- and inter-day) were found to be within the accepted variable limits.

Table 1.

Precision and accuracy of the method for determining pravastatin and aspirin in plasma samples.

| Analytes | Concentration added (ng/mL) | Intra-day precision and accuracy (n=12; 6 from each batch) |

Inter-day precision and accuracy (n=30; 6 from each batch) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration found (mean; ng/mL) | Precision (%) | Accuracy (%) | Concentration found (mean; ng/mL) | Precision (%) | Accuracy (%) | ||

| Pravastatin | 0.50 | 0.52 | 2.22 | 103.61 | 0.51 | 7.28 | 101.61 |

| 1.50 | 1.50 | 5.96 | 99.90 | 1.49 | 6.27 | 99.58 | |

| 96.22 | 96.63 | 5.46 | 100.42 | 94.06 | 7.29 | 97.75 | |

| 300.70 | 281.12 | 4.24 | 93.49 | 282.99 | 4.42 | 94.11 | |

| 400.93 | 396.27 | 4.55 | 98.84 | 395.66 | 5.24 | 98.68 | |

| Aspirin | 20.09 | 19.17 | 4.99 | 95.41 | 19.56 | 8.34 | 97.36 |

| 60.16 | 64.86 | 3.94 | 107.81 | 65.03 | 4.89 | 108.10 | |

| 388.13 | 366.73 | 6.17 | 94.49 | 384.37 | 7.04 | 99.03 | |

| 1008.13 | 919.57 | 2.73 | 91.22 | 937.73 | 6.69 | 93.02 | |

| 1600.20 | 1481.53 | 3.18 | 92.58 | 1488.89 | 4.17 | 93.04 | |

3.8. Extraction efficiency

A simple liquid/liquid extraction with methyl tertiary butyl ether proved to be robust and provided cleanest samples. The recoveries of analytes and the IS were good and reproducible. The mean overall recoveries (with the precision range) of pravastatin, aspirin and IS were 61.65±2.39% (1.75–4.52%), 51.24±1.26% (1.88–3.49%) and 65.46±1.60% (1.60–3.69%), respectively.

3.9. Dilution integrity

The upper concentration limits can be extended to 960.46 ng/mL for pravastatin and 3219.20 ng/mL for aspirin by 1/2 and 1/4 dilutions with screened human blank plasma. The mean back-calculated concentrations for 1/2 and 1/4 dilution samples were within 85–115% of their nominal value. The coefficients of variation (%CV) for 1/2 and 1/4 dilution samples were less than 15%.

3.10. Stability studies

In the different stability experiments carried out viz. bench top stability (5 h at ice water bath), autosampler stability (46 h), freeze-thaw stability (3 cycles at ice water bath), reinjection stability (26 h), wet extract stability (43 h at 2–8 °C) and long-term stability at −70 °C for 56 day the mean % nominal values of the analytes were found to be within ±15% of the predicted concentrations for the analytes at their LQC and HQC levels (Table 2). Thus, the results were found to be within the acceptable limits during the entire validation.

Table 2.

Stability samples result for pravastatin and aspirin in human plasma (n=6).

| Stability test | Pravastatin |

Aspirin |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QC (spiked concentration, ng/mL) | Mean±SD (ng/mL) | Accuracy/stability (%) | Precision (%) | QC (spiked concentration, ng/mL) | Mean±SD (ng/mL) | Accuracy/stability (%) | Precision | |

| Aautosampler stability (at 5 °C for 46 h) | 1.50 | 1.44±0.04 | 95.61 | 2.47 | 60.16 | 58.09±1.14 | 96.56 | 1.96 |

| 400.93 | 367.64±22.05 | 91.70 | 6.00 | 1600.20 | 1543.25±38.11 | 96.44 | 2.47 | |

| Wet extract stability (at 2–8 °C for 43 h) | 1.50 | 1.48±0.02 | 98.91 | 1.13 | 60.16 | 57.69 ±1.66 | 95.89 | 2.87 |

| 400.93 | 380.29±12.08 | 94.85 | 3.18 | 1600.20 | 1531.53±34.01 | 95.71 | 2.22 | |

| Bench top stability (5 h in ice water bath) | 1.50 | 1.44±0.10 | 95.80 | 6.86 | 60.16 | 55.90±4.20 | 92.92 | 7.51 |

| 400.93 | 377.88±11.20 | 94.25 | 2.96 | 1600.20 | 1471.28±12.99 | 91.94 | 0.88 | |

| Freeze-thaw stability | 1.50 | 1.45±0.05 | 96.78 | 3.24 | 60.16 | 54.57 ±1.90 | 90.71 | 3.49 |

| 400.93 | 376.73±13.60 | 93.96 | 3.61 | 1600.20 | 1474.95±18.77 | 92.17 | 1.27 | |

| Reinjection stability (26 h) | 1.50 | 1.53±0.05 | 104.12 | 3.46 | 60.16 | 63.19 ±2.15 | 98.20 | 3.40 |

| 400.93 | 393.91±20.88 | 103.41 | 5.30 | 1600.20 | 1485.15±16.10 | 101.41 | 1.08 | |

| Long-term | 1.50 | 1.45±0.04 | 93.16 | 2.70 | 60.16 | 56.79±2.84 | 101.13 | 5.00 |

| Stability (at –70 °C for 56 day) | 400.93 | 410.98±15.27 | 106.20 | 3.72 | 1600.20 | 1575.42±66.27 | 95.33 | 4.21 |

Stock solutions of pravastatin, aspirin and the IS were found to be stable for 23 day at 2–8 °C. The percentage stability (with the precision range) of pravastatin, aspirin and the IS was 103.78% (3.32–3.56%), 95.22% (2.66–2.72%) and 98.74% (2.01–3.38%), respectively.

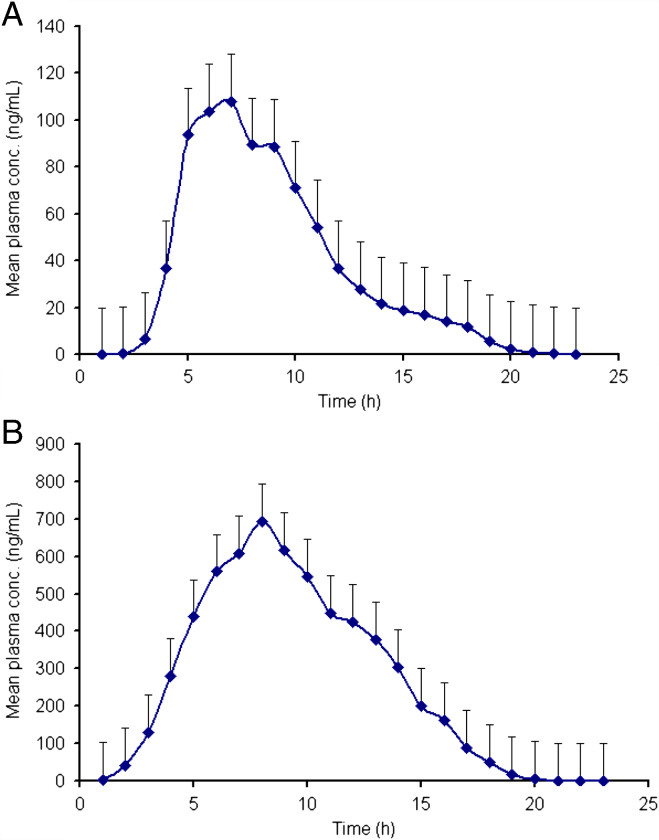

3.11. Pharmacokinetic study results

In order to verify the sensitivity and selectivity of this method in a real-time situation, the present method was used to test for pravastatin and aspirin in human plasma samples collected from healthy male volunteers (n=12). The mean plasma concentrations vs time profiles of pravastatin and aspirin is shown in Fig. 3(A) and (B), respectively. Pharmacokinetic results of pravastatin and aspirin are presented in Table 3. Pharmacokinetic results of pravastatin were in close proximity when compared with earlier reported values [20]. To date, to the best of our knowledge, no pharmacokinetic data on aspirin after oral administration of 81 mg tablet have been reported in the literature.

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration-time profile of (A) pravastatin and (B) aspirin in human plasma following oral dosing of 40 mg pravastatin sodium and 81mg aspirin tablets to healthy volunteers (n=12).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of pravastatin and aspirin (n=12, Mean±SD).

| Parameter | Pravastatin | Aspirin |

|---|---|---|

| tmax (h) | 0.60±0.17 | 0.66±0.21 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 94.65±46.10 | 872.19±209.86 |

| AUC0–t (ng h/mL) | 153.46±61.05 | 1175.09±422.10 |

| AUC0–inf (ng h/mL) | 156.99±61.99 | 1188.22±433.03 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.36±0.32 | 1.03±0.27 |

| Kel (h−1) | 2.58±1.06 | 0.72±0.18 |

4. Discussion

To date, no reports are available for the simultaneous quantification of pravastatin and aspirin in any of the matrices. Validated methods are essential for the determination of pravastatin and aspirin concentrations in human plasma for bioequivalence studies. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first validation report for an LC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous assay of pravastatin and aspirin using the convenience of a single-step extraction procedure. The reported method is simple, rugged and rapid due to utilization of short run time of 2.0 min for each sample analysis. The method uses single IS with simple sample preparation technique (LLE).

5. Conclusion

The LC–MS/MS assay reported in this paper is rapid, simple, specific and sensitive for simultaneous quantification of pravastatin and aspirin in human plasma and is fully validated according to commonly acceptable FDA guidelines. The method showed suitability for pharmacokinetic studies in humans. The cost-effectiveness, simplicity of the assay and usage of liquid–liquid extraction, and sample turnover rate of less than 2.0 min per sample, make it an attractive procedure in high-throughput bioanalysis of pravastatin and aspirin. From the results of all the validation parameters, we can conclude that the developed method can be useful for BA/BE studies and routine therapeutic drug monitoring with the desired precision and accuracy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Wellquest Clinical Research Laboratory, Hyderabad for providing necessary facilities for carrying out this study.

Contributor Information

Srinivasa Rao Polagani, Email: srinu_polagani@yahoo.co.in.

Venkateswarlu Gandu, Email: venkateshwarlugoud@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Dagli N., Yavuzkir M., Karaca I. The effects of high dose pravastatin and low dose pravastatin and ezetimibe combination therapy on lipid glucose metabolism and inflammation. Inflammation. 2007;30:230–235. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain K.S., Kathiravan M.K., Somani R.S. The biology and chemistry of hyperlipedemia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:4674–4699. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood D., Backer D.G., Faergeman O. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the second joint task force of european and other societies on coronary prevention. Eur. Heart J. 1998;19:1434–1503. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson T.A., Laurora I., Chu H. The Lipid Treatment Assessment Project (L-TAP): a multicenter survey to evaluate the percentages of dyslipidemic patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy and achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:459–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sueta C.A., Chowdhury M., Boccuzzi S.J. Analysis of the degree of undertreatment of hyperlipidemia and congestive heart failure secondary to coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999;83:1303–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson M.H., Toth P.P. Comparative effects of lipid-lowering therapies. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2004;47:73–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corsini A., Bellosta S., Baetta R. New insights into the pharmocodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of statins. J. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;84:413–428. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backer D.G., Ambrosioni E., Borch-Johnsen K. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third joint task force of european and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2003;24:1601–1610. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quion A.V., Jones P.H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of pravastatin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1994;27:94–103. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199427020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lennernas H., Fager G. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: similarities and differences. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:403–425. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatanaka T. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of pravastatin: mechanisms of pharmacokinetic events. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2000;39:397–412. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200039060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan H.Y., DeVault A.R., Wang-Iversen D. Steady state serum concentrations of pravastatin and digoxin when given in combination. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1990;30:1128–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burch J.W., Standford N., Majerus P.W. Inhibition of platelet prostaglandin synthetase by oral aspirin. J. Clin. Invest. 1978;61:314–319. doi: 10.1172/JCI108941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennekens C.H., Sacks F.M., Tonkin A. Additive benefits of pravastatin and aspirin to decrease risks of cardiovascular disease: randomized and observational comparisons of secondary prevention trials and their meta-analyses. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004;164:40–44. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. DHHS, F.D.A., CDER. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Veterinary Medicine (CV). Available at: 〈http://www/fda.gov/cder/guidance/index.htm〉, 2001.

- 16.Xu X., Koetzner L., Boulet J. Rapid and sensitive determination of acetylsalicylic acid and salicylic acid in plasma using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry: application to pharmacokinetic study. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2009;23:973–979. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawabata K., Samata N., Urasaki Y. Quantitative determination of pravastatin and R-416, its main metabolite in human plasma, by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2005;816:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsikas D., Tewes K.S., Gutzki F.-M. Gas chromatographic–tandem mass spectrometric determination of acetylsalicylic acid in human plasma after oral administration of low-dose aspirin and guaimesal. J. Chromatogr. B. 1998;709:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caslavska J., Thormann W. Rapid analysis of furosemide in human urine by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence and electrospray ionization-ion trap mass spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. B. 2002;770:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Z., Neirinck L. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with negative ion tandem mass spectrometry for determination of pravastatin inhuman plasma. J. Chromatogr. B. 2003;783:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]