Abstract

Background & objectives:

Depression among adolescents is a rising problem globally. There is a need to understand the factors associated with depression among adolescents. This study was conducted to ascertain the prevalence of depressive disorders and associated factors among schoolgoing adolescents in government and private schools in Chandigarh, India.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 542 randomly selected schoolgoing adolescents (13-18 yr), from eight schools by multistage sampling technique. Depression was assessed using Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and associated factors by pretested semistructured interview schedule. Multivariate analysis was done to identify significant associated factors.

Results:

Two-fifth (40%) of adolescents had depressive disorders, 7.6 per cent major depressive disorders and 32.5 per cent other depressive disorders. In terms of severity, 29.7 per cent had mild depression, 15.5 per cent had moderate depression, 3.7 per cent had moderately severe depression and 1.1 per cent had severe depression. Significant associated factors included being in a government school, studying in class Xth and XIIth, rural locality, physical abuse by family members, alcohol use and smoking by father, lack of supportive environment in school, spending less time in studies, lower level of participation in cultural activities and having a boy/girlfriend. Significant predictors on binary logistic regression analysis were being in class Xth [odds ratio (OR)=5.3] and lack of self-satisfaction with own academic performance (OR=5.1).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our study showed that a significant proportion of schoolgoing adolescents suffered from depression. The presence of depression was associated with a large number of modifiable risk factors. There is a need to modify the home as well as school environment to reduce the risk of depression.

Keywords: Adolescents, depression, factors, patient health questionnaire, prevalence

Depression among adolescents is rising in all regions of the world1. Community and school sample studies from different parts of the world of adolescents have shown that depression is the most common psychiatric disorder among adolescents2. A meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of major depressive disorder among adolescents aged 13-18 yr to be 5.6 per cent3. One prospective longitudinal study of community-based sample from Chandigarh, north India, reported an annual incidence rate of depression to be 1.61/1000 children aged 10-17 yr4.

Depression has a complex, multifactorial causal structure. Many risk and protective factors have been reported in the literature. Besides gender and genetics, the important factors associated with depression in adolescents include low level of parental warmth, high levels of maternal hostility and escalating adolescent-parent conflict; in addition, perceived rejection by peers, parents and teachers predict increase in depressive symptoms in children and adolescents5,6. Depression and severe suicidal ideation are also linked to being bullied or to acting as bullies7. Lifestyle is another important issue, as factors indicative of adoption of non-traditional lifestyle are associated with an increase in prevalence of depression8.

Several studies from India have evaluated the risk factors for depression among adolescents9,10,11, but still there is a need to understand the various risk factors associated with depression among adolescents. The present study was done to ascertain the prevalence of depressive disorders among schoolgoing adolescents (13-18 yr) in Chandigarh in north India and explore the factors associated with depression.

Material & Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the city of Chandigarh, which has a population of 1,054,686 as per census 201112. Adolescents constitute 20-22 per cent of the total population. Chandigarh has 71 (39 government and 32 private) senior secondary schools13. This study was conducted from July 2012 to October 2013. All participants were included after obtaining written informed consent/assent. Written permission was obtained from the Director of Public Institutions and District Education Officer (DEO), Chandigarh, to conduct the study in various government run schools. For private schools, permission was obtained from principals. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Institute. Those who were found to have depression were advised to seek treatment.

To be included in the study, the participants were required to be in the age group of 13-18 years, studying in the class 9th to 12th in one of the senior secondary schools of Chandigarh. The sample size was estimated based on the prevalence data from the existing literature14. Accordingly, the sample size required was 492. In addition, a non-response of 10 per cent was considered; hence, a total of 542 schoolgoing adolescents were included in the study.

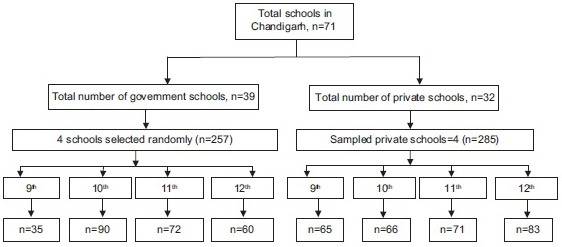

Multistage sampling was done. In the first stage, schools were chosen. In the second stage, students were chosen from each section of classes from 9th to 12th. In the first stage, all the government schools (n=39) and private schools (n=32) were numbered separately, and four random numbers were chosen from each group of schools. After this, lists of students from 9th to 12th were obtained and the students were numbered consecutively in each class as per their roll numbers. As per the study design, at least 15 students were included from each class from each school. This number was equally divided on the basis of number of sections in each class in a particular school. For example, if a class had five sections in a school then three students were chosen from each section. Students were chosen by selecting random roll numbers from each section of a class. It was observed that during data collection, less number of students were present in class 9th as compared to class 10th, especially in government schools. Sampling scheme from government and private schools is shown in Figure.

Figure.

Sampling scheme of schoolgoing adolescents in Chandigarh.

Data collection instruments: Two questionnaires were used in this study:

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A validated pretested modified patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)15 was used to screen the participants for depression. It is a modified, self-administered version of PRIME-MD, diagnostic instrument for common mental disorders15. PHQ-9 is the depression module which scores each of nine Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria16 from ‘0’ (not at all) to ‘3’ (nearly every day). It has been validated for use in primary care and adolescents15. It is not only a screening tool but also can be used to estimate severity of depression. The available Hindi version was used17. According to PHQ-9, major depressive disorder is diagnosed if five or more of the nine depressive symptoms are present at least for ‘more than half the days’ in the past two weeks, and one of the symptoms is depressed mood or anhedonia. One of the nine criteria (thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way) counts if present at all, regardless of duration. Other depressive disorder is diagnosed if two, three or four depressive symptoms are present at least ‘more than half the days’ in the past two weeks, and one of the symptoms is depressed mood or anhedonia. In terms of severity, those with score of 0-4 are categorized as having no or minimal depression, score of 5-9, 10-14, 15-19 and 20-27 indicate mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe depression, respectively15.

Questionnaire on factors associated with depression: The information on the risk and protective factors for depression was obtained using a structured pretested questionnaire. This risk and protective factors questionnaire was specifically designed for this study, based on the literature review5,6,7,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Opinion of the experts was obtained to increase its face validity and repeatability was tested by confirming test-retest hypothesis. This questionnaire had 84 items which included questions regarding socio-demographic profile, home and school environment, career-related issues, illness in family, lifestyle, substance abuse in father and its consequence, study, academic and career-related issues, peer-related issues including bullying, support from friends and internet use. Both, PHQ-9 and the risk factor questionnaire were self-administered.

Data analysis: Data were analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Categorical data were evaluated in terms of frequency and percentage and the continuous data were analyzed in terms of mean and standard deviation. Those with and without depression were compared using Chi-square test for identifying the factors associated with depression. Multivariate analysis was done and odd ratios calculated for significant independent variables.

Results

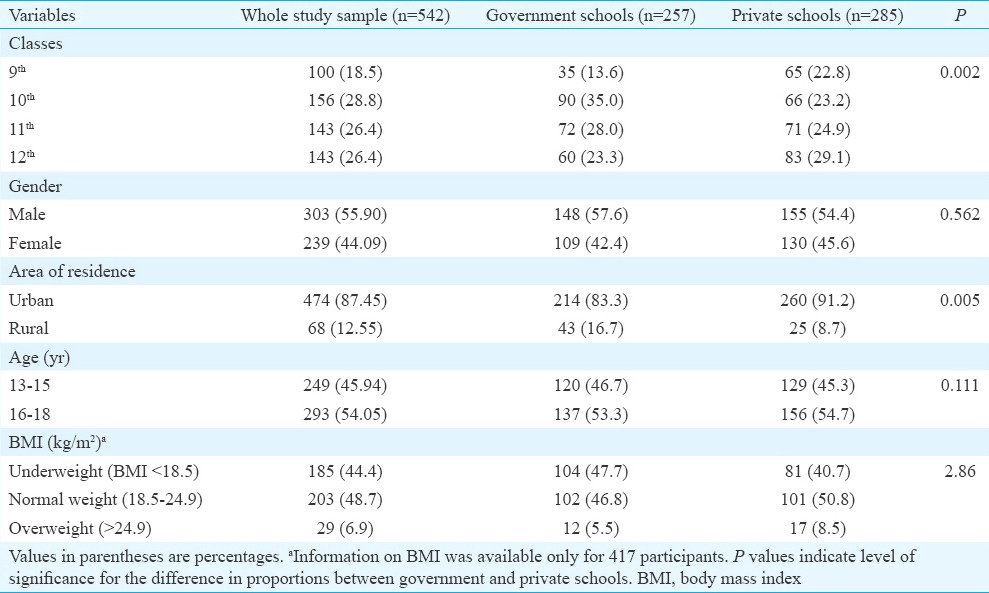

A total of 542 children were studied. Of these, 257 (47.4%) were studying in government and 285 (52.5%) in private schools. Maximum number of students were in class 10th followed by class 11th and 12th. Adolescent males outnumbered females. Majority of the participants were from urban area. In terms of body mass index (BMI), 203 (48.7%) participants had BMI in the normal range, 185 (44%) were underweight and 29 (6.9%) were overweight (Table I).

Table I.

Background profile of adolescents who participated in the study

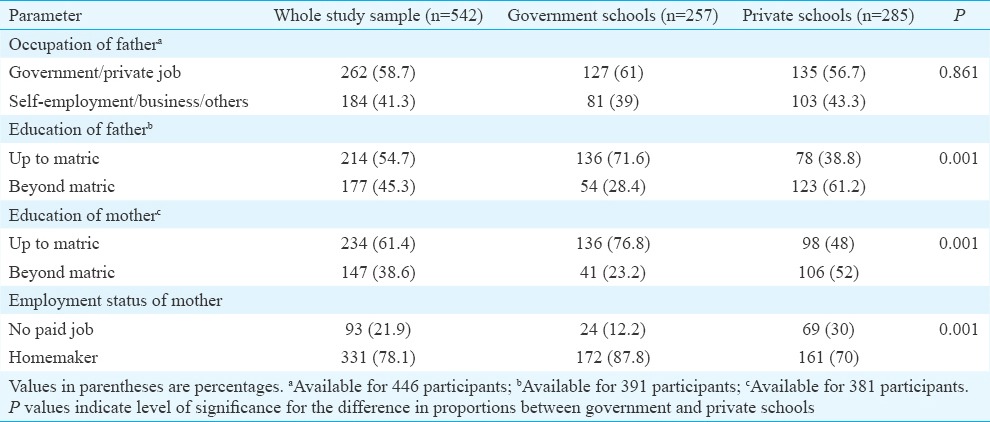

In terms of parental profile significantly higher proportions of parents (both father and mother) of children from private schools were educated beyond matric (Table II). However, in terms of profession of father, there was no significant difference between the children from government and private schools.

Table II.

Socio-demographic profile of parents of adolescents who participated in the study

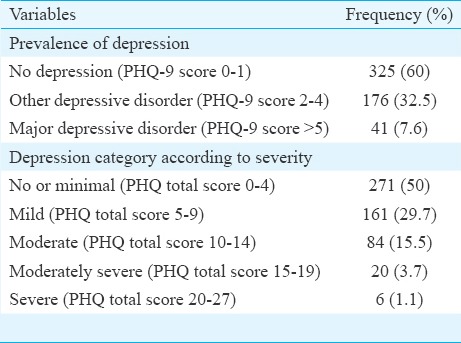

Prevalence of depressive disorders: As shown in Table III, the prevalence of major depressive disorder was found to be 7.6 per cent and that of other depressive disorders was 32.5 per cent. Sixty per cent children had no depression. On the basis of severity scale, 29.7 per cent had mild depression, 15.5 per cent had moderate depression, 3.7 per cent had moderately severe depression and 1.1 per cent had severe depression. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of depression between adolescents studying in class 10th and 12th.

Table III.

Prevalence and severity of depression as per modified Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) among adolescents

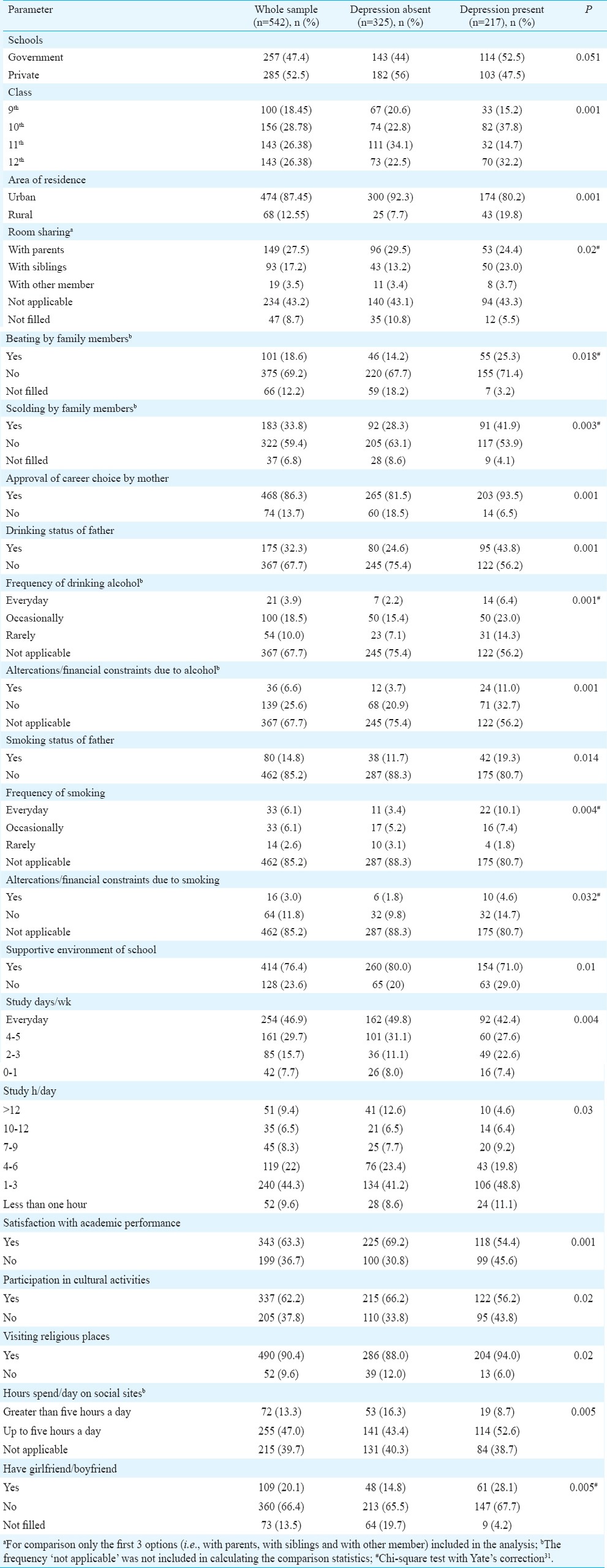

Factors associated with depression: For assessing the associated factors, the study sample was divided into two groups, i.e., those with depression and those without depression. The two groups were compared for the socio-demographic variables, type of school, class and the factors included in the associated factor questionnaire. As shown in Table IV, the prevalence of depression was significantly more in those attending the government schools, those in class Xth, from rural background, those sharing living room with siblings, who were beaten up by family members and those who were scolded by family members. In addition, significantly higher prevalence of depression was seen among those, whose mothers approved their career choice, father consuming alcohol, higher frequency of alcohol intake in father, presence of financial constraints and altercations in family due to intake of alcohol in father, smoking in father, higher frequency of smoking in father and altercations/financial constraints due to smoking of father, lack of supportive environment in school, spending lesser number of hours in studying per day and also per week, lack of satisfaction of self with academic performance, lack of participations in cultural activities in school, spending less time on the social sites and having a girlfriend/boyfriend. Other factors such as age group and gender, having a separate living room, use of substance by self, level of play activity in the school, support and motivation by parents and teachers, attitude of parents towards future of children, parental satisfaction with academic performance, approval of career choice by father, use of any other substance by a family member, working status of the mother, motivation by teachers, number of supportive teachers, bullying at school, peer pressure, use of internet, duration of internet use, use of social sites and involvement in sexual activity with a partner did not emerge as associated factors for depression.

Table IV.

Prevalence of depression as per various demographic characteristics

It was observed that significantly (P =0.001) more number of adolescents with major depressive disorders had suicidal ideation (85.4%) in the past two weeks as compared to those labelled with other depressive disorders (40.9%) and no depression (7.1%).

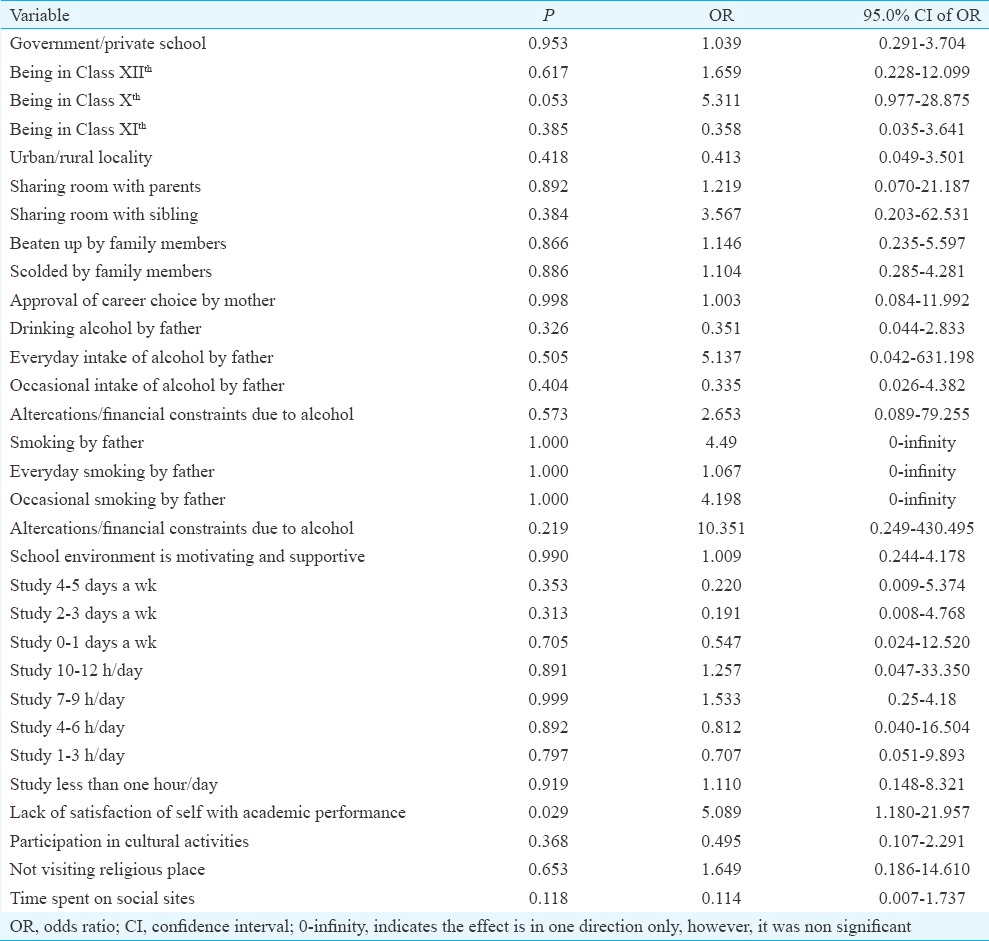

Predictors of depression: Binary logistic regression analysis: Based on the findings of bivariate analysis, the risk factors found to be significantly associated with the presence of depression were entered into binary logistic regression analysis with depression as a dependent variable and all other variables entered as independent variables. Significant associated factors with depression among adolescents after applying logistic regression were being in class Xth [adjusted odds ratio (OR)=5.311] and lack of self-satisfaction with own academic performance (adjusted OR=5.1) (Table V).

Table V.

Binary logistic regression analysis to evaluate the risk factors for depression

Discussion

This study included 542 participants with male preponderance and those from urban area forming larger proportion of the study sample. Lesser representation of students from rural area (12.6% overall) can be explained by proportion of rural population of Chandigarh, which is 2.75 per cent as per 2011 census11.

Results of this study showed that 40 per cent of the schoolgoing adolescents suffered from depressive disorders, with 7.6 per cent children having major depressive disorders and 32.5 per cent having other depressive disorders. Other such types of studies conducted in the past have shown mixed results. Many studies from different parts of the India have evaluated the prevalence of depression among adolescents using different screening instruments such as centre for epidemiological studies-depression scale9, Beck Depression Inventory11,18,19,20,21 in sample sizes varying from 64 to 1120 students of different classes. These studies have reported that the prevalence rates of depression vary from 18.4 to 65.6 per cent. Studies from different parts of the world also suggest that the prevalence rates of depression among adolescents vary from 18.4 to 79.2 per cent, depending on the study population and method of ascertainment of the diagnosis22,23,24. The difference in prevalence can be attributed to use of different diagnostic criteria (DSM III, IV), different definitions of depression such as clinical diagnosis or depressive symptoms, use of different assessment measures e.g. self-report, structured interviews or use of heterogeneous samples such as community versus clinical settings. The prevalence rate of 40 per cent observed in the present study suggests that depression is an important psychological morbidity among the adolescents. The present study showed several risk factors for depression among adolescents. Most of these findings are in consonance with some of the previous studies from India and other countries24,25,26,27.

The proportion of students with depression was more in government schools compared to private schools in this study. This difference can be explained by the socio-economic difference between the students of two types of schools. Socio-economic factors including education of father, income of father and education of mother were found to be significantly different among the students of government and private schools. These factors possibly influence the higher prevalence of depression among those from government schools. Besides these, various school-related factors such as lack of supportive environment in the school could also possibly play a role in higher prevalence of depression among those attending the government schools. Higher prevalence of depression among students of 10th and 12th class may be due to stress related to performance in final board examinations and preparation for competitive examinations. The present study showed that depression was more prevalent among students from rural area. This finding was similar to a previous study conducted in China, among college students28. The positive association between rural background and depression may be due to the fact that students from rural areas are more likely to have had poor family environments and considered as having a lower social status28.

Beating and scolding by parents or other family members were found to be significantly associated with depression as also shown earlier29. Other familial factors which were significantly associated with depression in the present study were alcohol use and smoking by fathers. Further, it was seen that there was dose-dependent relationship of depression with these, with higher frequency of alcohol use and smoking associated with higher risk of depression. This finding of the present study was also supported by the existing literature which suggested positive association of depression with the use of alcohol and substance abuse by father27.

School environment and career-related issues are two important domains, which can be major stressors if not handled well. In terms of school-related factors, the present study showed that supportive environment in the school acted as a protective factor for depression. Rather than following punishment model, the schools should have environment, which should be conducive for the students to open up about their problems. In addition, the schools should provide counselling services to students requiring help. Further, findings of the present study suggested that participation in cultural activities at school acted as a protective factor for depression.

Personal education-related factors were also found to be associated with depression. Findings of the present study suggest that students who were more regular in their studies (both in terms of number of days per week and number of hours spent per day on studies) were less depressed. Possibly regularity in studies led to less of stress of studies and examinations. Accordingly, there is a need on the part of the parents, teachers and clinicians to encourage regular studies. Another personal factor which was associated with depression was lack of self-satisfaction with the academic performance. This finding suggests the competitive nature of some of the student, who despite performing well in their studies may not be satisfied with their achievement and accordingly may experience low self-esteem, which possibly predisposes to development of depression.

Spending more time on social sites was found to be associated with less of depression. Possible reasons for these could be changing social structure according to which in the contemporary society, most of the students do not prefer to interact and play with each other on regular basis and in fact judge their friend circle on the basis of interaction on the social networking sites. This suggests that there is a need to study this variable further in detail to understand the relationship with depression in adolescents. Having a boyfriend/girlfriend was also associated with depression among schoolgoing adolescents. A previous study also suggested the same26.

In contrast to some of the earlier studies6,7,18,19,22,23,25,26,27,30 which have reported substance abuse by self, level of play activity in the school, support and motivation by parents and teachers, attitude of parents toward future of children, parental satisfaction with academic performance, approval of career choice by father, use of any other substance by a family member, working status of the mother, motivation by teachers, number of supportive teachers, bullying at school, peer pressure, use of internet, duration of internet use, use of social sites and involvement in sexual activity with a partner to be risk factors for depression among adolescents; in the present study, these variables did not emerge as risk factors for depression. Factors such as gender, BMI, type of school and age group were not observed to be associated with depression in our study. Thus, there is a further need to evaluate the role of these factors in depression among adolescents.

In multivariate analysis, only studying in class X and lack of satisfaction with academic performance emerged as the most important predictor of depression. This finding suggested that students should be provided adequate feedback about their performance to avoid lot of personal distress arising out of undue expectations from self.

The limitation of the study was that confirmation of the diagnosis by psychiatrist was not done due to feasibility issues. However, studies have shown that there is concordance in the diagnosis made on the basis of screening instruments and clinical assessment by psychiatrist17,32. School dropout adolescents were excluded from this study; hence, findings of the present study cannot be generalized to them. As this was a cross-sectional study, hence temporality could not be ascertained for associated factors of depression.

In conclusion, this study provided information regarding the magnitude of the problem of depression and many modifiable risk factors for depression among schoolgoing adolescents. There needs to be multisectoral response to this public health problem3,33. There is a need to convey the parents that maltreatment of adolescents by parents or family members, alcohol use and smoking in father might be the factors for depression among adolescents and emphasis should be laid on sharing of problems of adolescents with parents by making the home environment more conducive. For teachers and parents, it is important to evaluate the faculty perceptions of students related to their own undue expectations from their academic performance. Further, there is a need to emphasize regularity in studies for the students to prevent depression. School counsellors may be involved in screening adolescents with depressive disorders and appropriate referral. Community workers may be involved in identifying the depressive disorders among out of school adolescents so that they can get the treatment at the earliest34.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the Director Public Institution, DEO, Chandigarh, and principals of the selected school for allowing to conduct this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. Adolescents and mental health. [accessed on July 15, 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/mental_health/en/

- 3.Jane Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra S, Kohli A, Kapoor M, Pradhan B. Incidence of childhood psychiatric disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:101–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.49449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kistner J, Balthazor M, Risi S, Burton C. Predicting dysphoria in adolescence from actual and perceived peer acceptance in childhood. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:94–104. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan SA, Flynn C, Garber J. Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:745–55. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Marttunen M, Rimpelä A, Rantanen P. Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation in Finnish adolescents: School survey. BMJ. 1999;319:348–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarris J, O’Neil A, Coulson CE, Schweitzer I, Berk M. Lifestyle medicine for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma GK, Chahar KK, Jain L. To study the prevalence of depression and its sociodemographic variabels in school going children in Bikaner city. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2013;16:380–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vashisht A, Gadi NA, Singh J, Mukherjee MP, Pathak R, Mishra P. Prevalence of depression and assessment of risk factors among school going adolescents. Indian J Community Health. 2014;26:196–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayanthi P, Thirunavukarasu M, Rajkumar R. Academic stress and depression among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:217–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0609-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandigarh Population Census Data 2011. Chandigarh. 2011. [accessed on June 25, 2017]. Available from: http://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/chandigarh.html .

- 13.Department of Education Chandigarh Administration. Chandigarh. [accessed on June 25, 2017]. Available from: http://www.chdeducation.gov.in/schoolslist.asp .

- 14.Mohanraj R, Subbaiah K. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms among Urban adolescents of South India. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;6:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Frühe B, Sigl-Glöckner J, Schulte-Körne G. Screening for depression in adolescents: Validity of the patient health questionnaire in pediatric care. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:906–13. doi: 10.1002/da.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV; p. 866. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avasthi A, Varma SC, Kulhara P, Nehra R, Grover S, Sharma S. Diagnosis of common mental disorders by using PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma M, Sharma N, Yadava A. Parental styles and depression among adolescents. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2011;37:60–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bansal V, Goyal S, Srivastava K. Study of prevalence of depression in adolescent students of a public school. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:43–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair MK, Paul MK, John R. Prevalence of depression among adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:523–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02724294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basker M, Moses PD, Russell S, Russell PS. The psychometric properties of Beck Depression Inventory for adolescent depression in a primary-care paediatric setting in India. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2007;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daryanavard A, Madani A, Mahmoodi MS, Rahimi S, Nourooziyan F, Hosseinpoor M. Prevalence of depression among high school students and its relation to family structure. Am J Appl Sci. 2011;8:39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maharaj RG, Alli F, Cumberbatch K, Laloo P, Mohammed S, Ramesar A, et al. Depression among adolescents, aged 13-19 years, attending secondary schools in Trinidad: Prevalence and associated factors. West Indian Med J. 2008;57:352–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris TL, Molock SD. Cultural orientation, family cohesion, and family support in suicide ideation and depression among African American college students. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30:341–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patten CA, Gillin JC, Farkas AJ, Gilpin EA, Berry CC, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms in California adolescents: Family structure and parental support. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:271–8. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung SK. Life events, classroom environment, achievement expectation, and depression among early adolescents. Soc Behav Pers Int J. 1995;23:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: Predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:106–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng H, Li J, Loerbroks A, Wu J, Chen H. Rural/urban background, depression and suicidal ideation in Chinese college students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeds PM, Harkness KL, Quilty LC. Parental maltreatment, bullying, and adolescent depression: Evidence for the mediating role of perceived social support. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39:681–92. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.501289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison CM, Gore H. The relationship between excessive Internet use and depression: A questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and adults. Psychopathology. 2010;43:121–6. doi: 10.1159/000277001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yates F. Contingency table involving small numbers and the χ2 test. Supplement to the J Royal Stat Soc. 1934;1:217–35. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avasthi A, Grover S, Bhansali A, Kate N, Kumar V, Das EM, et al. Presence of common mental disorders in patients with diabetes mellitus using a two-stage evaluation method. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:364–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.156580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacob KS. Depression: A major public health problem in need of a multi-sectoral response. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136:537–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avasthi A, Ghosh A. Depression in primary care: Challenges and controversies. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:188–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]