Abstract

Percutaneous vascular embolization plays an important role in the management of various gynecologic and obstetric abnormalities. Transcatheter embolization is a minimally invasive alternative procedure to surgery with reduced morbidity and mortality, and preserves the patient's future fertility potential. The clinical indications for transcatheter embolization are much broader and include many benign gynecologic conditions, such as fibroid, adenomyosis, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), as well as intractable bleeding due to inoperable advanced-stage malignancies. The most well-known and well-studied indication is uterine fibroid embolization. Uterine artery embolization (UAE) may be performed to prevent or treat bleeding associated with various obstetric conditions, including postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), placental implantation abnormality, and ectopic pregnancy. Embolization of the uterine artery or the internal iliac artery also may be performed to control pelvic bleeding due to coagulopathy or iatrogenic injury. This article discusses these gynecologic and obstetric indications for transcatheter embolization and reviews procedural techniques and outcomes.

Keywords: Angiography, embolization, uterine artery

Introduction

Transcatheter embolization therapies have become a prime focus of interventional radiologists, who use various embolic materials to treat a broad range of conditions, from benign vascular malformations to malignancies. Current embolization procedures performed in the female pelvis include embolization for management of symptomatic fibroids, management of bleeding associated with various obstetric conditions, including postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), abnormal placental implantation, ectopic pregnancy, and ovarian vein embolization for treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome. There are no absolute contraindications to embolization for treatment of a life-threatening hemorrhage. Contraindications to elective embolization include previous pelvic irradiation; acute or chronic pelvic infection; refractory coagulopathy; use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, which may cause constriction of the uterine arteries; intrauterine pregnancy with normal placental implantation; renal impairment, and severe allergy to contrast material.[1] The article discusses the indications for transcatheter embolization, describes interventional techniques, and discusses the potential limitations and complications of embolization.

Patient Evaluation

All the patients considered for uterine artery embolization (UAE) should be evaluated by a gynecologist and an interventional radiologist. A detail menstrual history followed by clinical evaluation is important to exclude other cause of menorrhagia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging modality to evaluate patients before and after UAE. MRI allows an accurate pre-procedure selection of patients and delineation of the vascular anatomy. Ultrasound (US) is an easily available and quick imaging modality to evaluate fibroid. Both transvaginal and abdominal US may be needed for a complete evaluation. However, US is a less sensitive modality for complete fibroid mapping and delineation of coexistent pathologies in the uterus and adnexa. Nevertheless, US allows rapid evaluation and has the advantages of being less expensive and more readily available than MRI.[2]

The choice of preprocedural prophylaxis with antibiotic varies from institute to institute. Prophylactic antibiotic may be given as intravenous bolus 30 min before the procedure. Every patient should be catheterized with a Foley catheter before the procedure which will not only empty the bladder, but also prevents obscuration of uterus by contrast filled bladder.

Basic Angiographic and Embolization Techniques

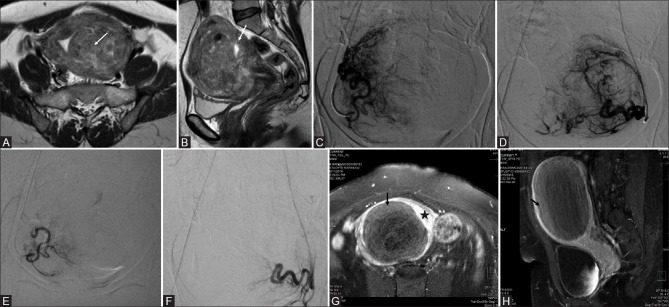

Transcatheter embolization is performed in a digital subtraction angiography (DSA) suite or in an operating room with similar angiographic equipment. Moderate sedation with short-acting narcotics and benzodiazepines is administered intravenously to relieve pain and anxiety. After sterile preparation of the groin is completed, the common femoral artery is accessed with a 5- or 6F arterial sheath. UAE is also possible via transradial access (TRA) and published literature suggests that TRA offers a feasible alternative to TFA for patients undergoing UAE.[3] The advantage of TRA is that patient can self-compress allowing early mobilization following the procedure. After access through transfemoral or transradial route, the initial diagnostic aortography (to demonstrate the basic arterial anatomy) followed by selective and superselective arteriography is performed. A 4- or 5-F selective angiographic catheter is used to achieve access to the internal iliac artery, and a 2- or 3-F microcatheter is used for superselective catheterization of uterine artery and its branches. Uterine artery arises from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery as first or second branch in >50% of cases and is well seen on the contralateral oblique projection.[4] However, variations and aberrant origin is known and may require special projection to document it. Commonly, Robert's Uterine Catheter (RUC) is used to hook the uterine artery in both sides as it has a particular hinge to allow ipsilateral catheterization of the uterine artery. Similarly, a multipurpose catheter can be used to hook uterine artery where a Waltman loop is created to enter the ipsilateral uterine artery [Figure 1].

Figure 1(A-C).

Schematic image showing hooking of left internal iliac artery in a conventional way (A), followed by creation of a “Waltman loop” (B) by rotating the catheter within the aorta and then pulling it towards ipsilateral side of puncture to catheterize the ipsilateral internal iliac artery (C)

The choice of embolic material is determined by multiple factors, including the cause, the extent of bleeding, number of vessels, and dynamics of vascular lesion involved. Embolic materials are generally categorized into temporary or permanent agents. The prototypic temporary embolic agent is absorbable gelatin sponge, a water insoluble gelatin that allows vessel recanalization within several weeks after placement. Permanent embolic materials include particulate agents [polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) foam and microspheres), metallic coils and plugs, and liquid polymers. Absorbable gelatin sponge and particulate agents are not radiopaque, but are injected with iodinated contrast material. Coils are made of stainless steel or platinum and available in a large number of sizes and shapes. Coils are most useful for occlusion of focal arterial abnormalities or injuries. Coils may be used in conjunction with either a temporary or a permanent particulate agent. Glue (n-Butyl cyanoacrylate) is a permanent liquid embolic that is mixed with lipiodol to make it radiopaque. The admixture ratio can be adjusted to slow or speed the time to polymerization and adjust the distance of its delivery from the injection point into the circulation. Unlike particulate embolic agents, metallic devices and liquid embolic agents are visible on postprocedural images.

Post Procedural Pain Management

Pain management after the procedure is an integral part of UAE. Patient counseling and active pain management may contribute to safe and successful patient outcome, without increasing complications. A standing regimen for pain including superior hypogastric nerve block (SHNB) is a very effective way to reduce pain after UAE especially within the first few hours. SHNB is performed by advancing a 21G needle from the abdominal wall below the umbilicus to the anterior portion of the fifth lumbar vertebral body with a cranio-caudal tilt of 5°–15° and injecting 20 mL local anesthesia (ropivacaine 0.75%).[5] Routine non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and opiods can be used for pain relief. Injecting intra-arterial 1% lidocaine in the uterine arteries is associated with reduced postprocedural pain and narcotic agent dose after UAE.[6]

Complications of Embolization

Overall complication rates for obstetric and gynecologic embolization procedures are 6–9%.[7,8,9] Reported complications of elective embolization include complications related to the angiographic procedure (e.g., groin puncture site hematoma, arterial dissection, and contrast medium-associated allergy or nephrotoxic effect) and complications that are secondary to embolization. Postembolization syndrome, characterized by pain, fever, nausea, and leukocytosis immediately after the procedure and lasting as long as several days, is reported to have occurred in 50% of patients.[7,10] It is treated with analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications. Other complications may include vaginal discharge and passage of fibroid tissue. Other rare complications like uterine necrosis or rupture, sepsis, abscess, and ischemia of adjacent tissue also have been reported.[8,11] Non-targeted embolization may occur and cause bladder or rectal necrosis or sexual dysfunction. Ovarian failure due to unintended embolization via utero-ovarian anastomoses can cause amenorrhea.[8,12,13] For patients aged 45 years or older, there is approximately a 15% chance of menopause within a year after UAE.[14]

Gynecological Indications for Transcatheter Embolization

Uterine fibroids

Uterine fibroids or leiomyomas, the most common pelvic tumors in women are benign neoplasms composed of uterine smooth muscle cells and fibrous connective tissue. Fibroid-related symptoms are most commonly divided into menstrual disturbances like menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, and bulk-related symptoms like urinary frequency and constipation. Absolute contraindications for UAE include known or suspected pregnancy, gynecologic malignancy, and current uterine or adnexal infection. Relative contraindications include contrast material allergy and coagulopathy renal failure.[2] Special consideration should be given according to location of the fibroid as seen on MRI. Intracavitary fibroids are more likely to be expelled and may be associated with more complications. Pedunculated subserosal fibroids has the potential risk of detachment and so contraindication for UAE. Moreover, cervical fibroids appear to be resistant to UAE.[2]

Technique

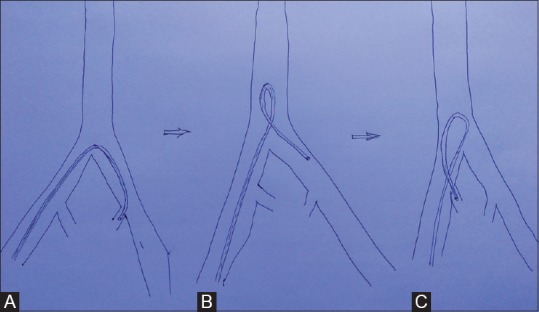

The technique is similar to the general UAE protocol outlined above. During the procedure evaluation of two branches are important. First is the cervicovaginal branch and one should try to embolize beyond its origin to avoid vaginal ischemia. Second is the collaterals from ovarian artery to prevent reflux into ovarian arteries. Permanent particulate agents (PVA) with a diameter at or greater than 500 μm are used.[15,16] The end-point is a “pruned-tree” appearance with sluggish forward flow in the main uterine artery and static column of contrast in uterine artery with only stump filling when contrast is injected into internal iliac artery [Figure 2]. The procedure may be performed with a two-catheter approach, which has the advantage of allowing simultaneous bilateral embolization and reduced fluoroscopic time.[17] Causes of failure include technical difficulties in uterine artery catheterization; arterial spasm; delayed redistribution of embolic particles and restoration of flow; and arterial supply to fibroids from ovarian arteries.[18] The treated fibroids may regrow or new fibroids may form that become symptomatic especially in younger women.[11,18,19]

Figure 2(A-H).

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of a premenopausal patient with pelvic pain and menorrhagia reveal multiple leiomyomas with heterogeneous signal causing indentation of the endometrium (arrow in A and B). (C and D) digital subtraction angiography (DSA) images obtained with selective injections of the right (C) and left (D) uterine arteries demonstrate an enlarged, hypervascular uterus with multiple tortuous branches and lesion blush bilaterally. Bilateral uterine artery embolization (UAE) was performed by using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles with a diameter of 500–700 μm. (E and F) Post-UAE DSA images show occlusion of multiple tortuous branches of both the right (E) and left (F) uterine arteries with static column of contrast in uterine arteries and almost complete disappearance of the lesion blush. Contrast enhanced MRI (G and H) done after 1 month of embolization showing complete nonenhancement of the fibroid (black arrow) surrounded by normally enhancing uterine wall (asterisk)

In terms of assessment of the success of the procedure, the Cochrane review (2012) evaluated five randomized controlled trials of UAE compared with hysterectomy and myomectomy. The morbidity was found to be less with UAE with a shorter hospital stay and disability at comparable patient satisfaction rates. Even the clinical success rates in terms of improvement of menorrhagia (82–90%) and dysmenorrhea (77–86%) have been reported to be high. However, the complications (25–50%) have also been reported to be higher with UAE. This is because these complications include the minor ones like postembolization syndrome as well.[20]

The reintervention rates reported in the 2008 FIBROID registry (involving 3160 UAE patients) are also low. Repeat UAE was performed in 1.83% patients with hysterectomy in 9.79% and myomectomy in 2.82% in a 3-year follow-up period for 1278 patients.[20]

In the consensus guidelines for “Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE) for Fibroid Treatment” it has been suggested to perform a post-treatment evaluation by a gynecologist approximately 6 months after the procedure. This evaluation also includes imaging (US with or without MRI). The evaluation of patient symptom response has to be done in conjunction with the imaging findings for deciding further management (reintervention, myomectomy, or hysterectomy).[21]

The choice of therapies for patient who wish to become pregnant after treatment of fibroids is more difficult. The only randomized controlled trial comparing myomectomy with UAE for fibroids showed similar initial levels of improvement in symptoms, quality of life, and ovarian function 6 months after treatment.[22] The same group reported that after 2 years of treatment, myomectomy had better reproductive outcomes (78%) as compared to UAE (50%) suggesting a clear advantage of myomectomy for patients seeking to become pregnant.[23] In women following UAE, the incidence of complications in later pregnancy was much lower and comparable with the rate of pregnancy after myomectomy, and this was confirmed by another study matching the results of UAE and laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion.[24] Women should be properly counseled on a case to case basis, about the reproductive and menopausal status following UAE and their possible outcomes regarding fertility.

Uterine Arteriovenous Malformations

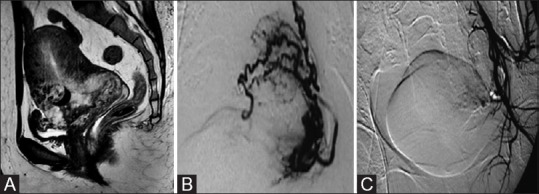

Uterine arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are rare vascular lesions that consist of communications between arteries and veins without intervening capillaries. They may be congenital or acquired. Congenital uterine AVMs consist of multiple small vascular connections that often involve adjacent pelvic structures. Acquired uterine AVMs consist of larger vascular connections and often result from prior instrumentation (cesarean section, dilation and curettage), infection, retained products of conception, fibroids, endometriosis, gestational trophoblastic disease, or gynecologic malignancy.[25,26,27,28] Although angiography remains the gold standard, Doppler ultrasonography (USG) is also a good noninvasive technique for diagnosis. Embolization is often the preferable method of treatment in order to avoid a hysterectomy in patients of child-bearing age. The separate and combined use of various embolic agents, including N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue, PVA particles, metallic coils, and absorbable gelatin sponge, has been described.[27] Occlusion of the AVM nidus may be performed with glue [Figure 3]. If access to the nidus is difficult, coil embolization of the feeding arteries or nonselective embolization of the uterine arteries may be performed by using PVA particles, absorbable gelatin sponge, or both. Multiple embolization procedures may be needed to occlude the entire AVM in some patients.

Figure 3(A-C).

(A) Sagittal T2W magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image of a 28-year-old woman shows a large intramural heterogeneous signal intensity uterine mass with prominent flow voids suggestive of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM). (B) Left internal iliac DSA showed high-flow intrauterine AVM. Embolization was performed with a combination of PVA particles and glue to occlude the vessels at the nidus. (C) Postembolization internal iliac digital subtraction angiography (DSA) image (same patient as in b) shows no filling of the AVM

Adenomyosis

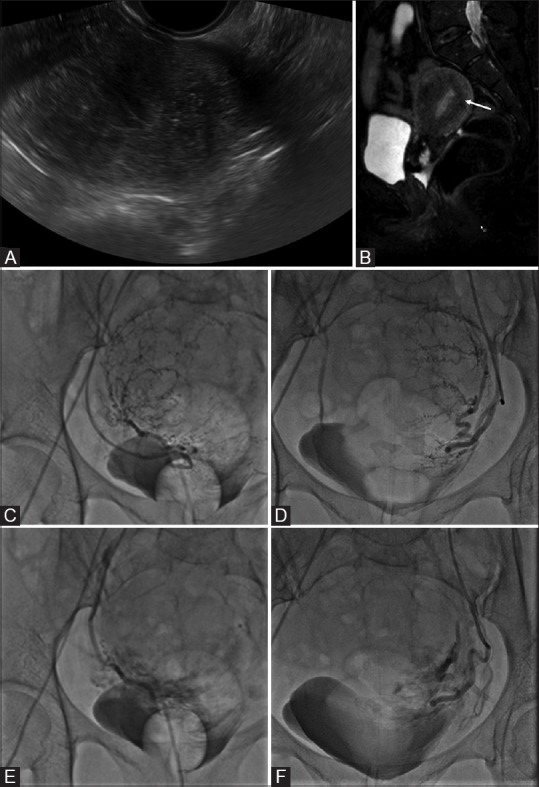

Adenomyosis is a benign, non-neoplastic process characterized by the ectopic proliferation of endometrial tissue into the myometrium with smooth muscle hypertrophy. MRI is the definitive modality for diagnosis, which is based on a finding of thickening of the myometrial junctional zone. Although the definitive treatment for this condition is hysterectomy, UAE has been used as an alternative to hysterectomy in symptomatic patients. The technique and protocol used is the same as that used for uterine fibroids [Figure 4]. In a retrospective review of the literature that included 511 women in 15 studies, 83% of the patients reported an improvement in symptoms at an average follow-up time of 9.4 months.[29] However, only 64.9% of subjects reported a sustained improvement in symptoms at an average follow-up time of 40.6 months.[29] Although these data do not definitively establish a role for UAE in the treatment of adenomyosis, they do suggest that UAE is a viable alternative to hysterectomy for this indication.[29]

Figure 4(A-F).

(A) Transvaginal ultrasound image of a 50-year-old woman presenting with menorrhagia reveals an enlarged uterus with heterogeneous echopattern. (B) Sagittal T2W magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows extensive adenomyosis with diffuse low T2 SI thickening of the junctional zone (arrow). (C and D) digital subtraction angiography (DSA) images obtained with selective injections of the right (C) and left (D) uterine arteries demonstrate an enlarged, hypervascular uterus. Bilateral uterine artery embolization (UAE) was performed by using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles with a diameter of 500–700 μm. (E, F) Post-UAE DSA images show occlusion of multiple tortuous branches of both the right (E) and the left (F) uterine arteries

Gynecologic Malignancies

In advanced stage gynecologic malignancies, transcatheter embolization should be considered for the management of intractable bleeding if conservative measures fail. Embolization of the internal iliac artery and uterine artery in this setting has been performed with various embolizing agents. The risk for recurrent bleeding is common, particularly when absorbable gelatin sponge is used.[28] Successful embolization has been reported in patients with cervical and endometrial cancers, choriocarcinoma–gestational trophoblastic disease, and vulvovaginal metastatic disease.[25,30,31,32,33]

Obstetrical Indications for Transcatheter Embolization

Postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) remains one of the major causes of maternal mortality worldwide.[34] PPH is defined as blood loss of more than 500 cc after vaginal delivery or 1000 cc after cesarean section.[26,35] The etiology of PPH includes uterine atony, placental implantation abnormality, retention of products of conception, infection, and coagulopathy.[25,35,36,37,38] Uterine tamponade techniques and exploratory laparotomy with possible hysterectomy are used in the setting of ongoing and uncontrollable bleeding. Women with persistent/non-responding PPH despite conservative treatment modalities may benefit from transcatheter embolization. Primary treatment methods include correction of hypovolemic shock and coagulation abnormalities, pharmacologic measures such as administration of vasopressor medication, uterine balloon tamponade, and vaginal packing. The most commonly used embolic agent is absorbable gelatin sponge or PVA particles. Metallic coils or vascular plugs may be used in embolization of proximal sites of injury in large arteries. Embolization with these methods is effective in 83–95% of women, may be repeated, and does not preclude subsequent surgical intervention.[35,39,40]

Abnormal Placentation

The spectrum of placental implantation abnormalities known collectively as placenta accreta, which includes placenta accrete vera (attachment of chorionic villi to myometrium without myometrial invasion), placenta increta (attachment of villi with partial invasion of myometrium), and placenta percreta (attachment of villi with penetration through myometrium). Risk factors for placenta accreta include placenta previa, previous cesarean delivery, multiparity, advanced maternal age, and prior dilatation and curettage.[41] Placenta accreta is usually diagnosed at USG Doppler evaluation of the placenta-myometrium interface; however, the degree of invasion and involvement of adjacent structures are better evaluated by MRI. Those affected with placenta accreta are at risk for uncontrollable peripartum hemorrhage, fetal loss, postoperative infection, and uterine rupture.[42,43] The optimal management is planned delivery at approximately 34–35 gestational weeks to reduce hemorrhagic complications. The most common approach for delivery is cesarean section with hysterectomy; however, peripartum transcatheter embolization has been used successfully to allow preservation of the uterus.[42,43,44] Angiographic balloon occlusion catheters are placed in the internal iliac arteries via bilateral femoral artery approaches before the cesarean section is performed [Figure 5]. Immediately after delivery, the bilateral occlusion balloons are inflated to occlude the blood flow and control the hemorrhage. If bleeding persists, embolization of the uterine arteries can be performed by using absorbable gelatin sponge or coils.[26,42,45] Aortography should be performed at the end to verify that there is no blood supply to the uterus from the ovarian or inferior epigastric arteries.

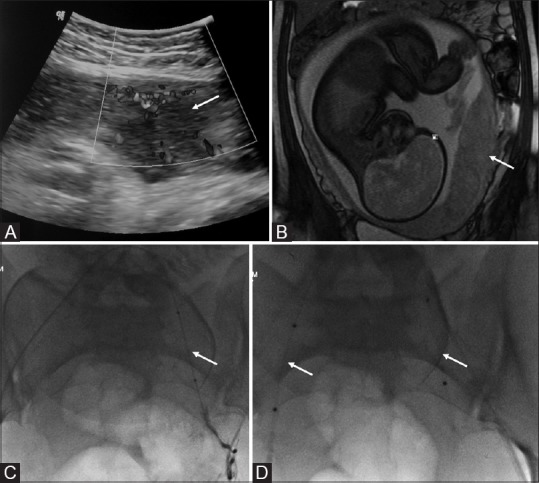

Figure 5(A-D).

(A) Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound (US) image shows a gap in the myometrial blood flow (arrow). (B) Coronal True fast imaging with steady state precession (TruFISP) MR image shows discontinuity of the hypointense inner myometrial layer with the placenta bulging into the myometrium (arrow) suggestive of placenta increta. (C) digital subtraction angiography (DSA) image of the same patient-showing placement of balloon within the left internal iliac artery (arrow). (D) Final fluoroscopic image demonstrates the deflated balloons in position in bilateral internal iliac arteries (arrows). The balloons were inflated immediately prior to delivery

Ectopic Pregnancy

Emergency UAE may be performed for severe bleeding after medical or surgical therapy for ectopic pregnancy. UAE has been used with success to treat cervical ectopic pregnancy [Figure 6], both as a stand-alone method and in combination with methotrexate therapy.[46,47,48,49]

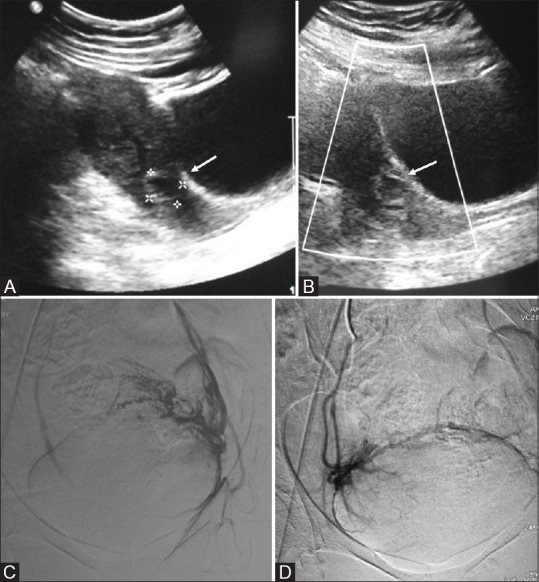

Figure 6(A-D).

(A) Transabdominal ultrasound image of a 28-year-old patient with 8 weeks amenorrhoea showing small gestational sac in the cervical canal (arrow). (B) Color Doppler reveals a ring of peripheral vascularity (arrow) suggestive of ectopic cervical pregnancy. Pre-curettage angioembolization (C and D) were performed to reduce vascularity

Conclusion

UAE has been demonstrated to be a safe and effective treatment for various female pelvic diseases. It is an effective alternative treatment option for patients who are interested in a minimally invasive uterine sparing therapy especially for symptomatic patients with higher surgical risk and poor candidates for surgery. Treatment recommendations need to be based on the patient's status as a whole, extent of the pathology, imaging findings, the patient's suitability for surgery, and her interest in future childbearing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Andrews RT, Spies JB, Sacks D, Worthington-Kirsch RL, Niedzwiecki GA, Marx MV, et al. Patient care and uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:S307–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulman JC, Ascher SM, Spies JB. Current concepts in uterine fibroid embolization. Radiographics. 2012;32:1735–50. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick NJ, Kim E, Patel RS, Lookstein RA, Nowakowski FS, Fischman AM. Uterine artery embolization using a transradial approach: Initial experience and technique. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelage JP, Le Dref O, Soyer P, Jacob D, Kardache M, Dahan H, et al. Arterial anatomy of the female genital tract: Variations and relevance to transcatheter embolization of the uterus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:989–94. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.4.10587133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binkert CA, Hirzel FC, Gutzeit A, Zollikofer CL, Hess T. Superior hypogastric nerve block to reduce pain after uterine artery embolization: Advanced technique and comparison to epidural anesthesia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:1157–61. doi: 10.1007/s00270-015-1118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noel-Lamy M, Tan KT, Simons ME, Sniderman KW, Mironov O, Rajan DK. Intraarterial lidocaine for pain control in uterine artery embolization: A prospective, randomized study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrillo TC. Uterine artery embolization in the management of symptomatic uterine fibroids: An overview of complications and follow-up. Semin Interv Radiol. 2008;25:378–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1102997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitamura Y, Ascher SM, Cooper C, Allison SJ, Jha RC, Flick PA, et al. Imaging manifestations of complications associated with uterine artery embolization. RadioGraphics. 2005;25:S119–32. doi: 10.1148/rg.25si055518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spies JB, Spector A, Roth AR, Baker CM, Mauro L, Murphy-Skrynarz K. Complications after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:873–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soyer P, Morel O, Fargeaudou Y, Sirol M, Staub F, Boudiaf M, et al. Value of pelvic embolization in the management of severe postpartum hemorrhage due to placenta accreta, increta or percreta. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajan DK, Beecroft JR, Clark TW, Asch MR, Simons ME, Kachura JR, et al. Risk of intrauterine infectious complications after uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1415–21. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141337.52684.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelage JP, Le Dref O, Soyer P, Kardache M, Dahan H, Abitbol M, et al. Fibroid-related menorrhagia: Treatment with superselective embolization of the uterine arteries and midterm follow-up. Radiology. 2000;215:428–31. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ma11428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker WJ, Pelage JP. Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: Clinical results in 400 women with imaging follow up. BJOG. 2002;109:1262–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spies JB, Roth AR, Gonsalves SM, Murphy-Skrzyniarz KM. Ovarian function after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: Assessment with use of serum follicle stimulating hormone assay. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:437–42. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilhim T, Pisco JM, Duarte M, Oliveira AG. Polyvinyl alcohol particle size for uterine artery embolization: A prospective randomized study of initial use of 350-500 μm particles versus initial use of 500-700 μm particles. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Firouznia K, Ghanaati H, Sanaati M, Jalali AH, Shakiba M. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids: A series of 15 pregnancies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1588–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costantino M, Lee J, McCullough M, Nsouli-Maktabi H, Nsrouli-Maktabi H, Spies JB. Bilateral versus unilateral femoral access for uterine artery embolization: Results of a randomized comparative trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spies JB, Bruno J, Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Magee ST, Ascher SA, Jha RC. Long-term outcome of uterine artery embolization of leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:933–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000182582.64088.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers ER, Barber MD, Gustilo-Ashby T, Couchman G, Matchar DB, McCrory DC. Management of uterine leiomyomata: What do we really know? Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:8–17. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silberzweig JE, Powell DK, Matsumoto AH, Spies JB. Management of uterine fibroids: A focus on Uuerine-sparing interventional techniques. Radiology. 2016;280:675–92. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016141693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kröncke T, David M. Uterine artery embolization (uae) for fibroid treatment-results of the 5th radiological gynecological expert meeting. Rofo. 2015;187:483–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mara M, Fucikova Z, Maskova J, Kuzel D, Haakova L. Uterine fibroid embolization versus myomectomy in women wishing to preserve fertility: Preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mara M, Maskova J, Fucikova Z, Kuzel D, Belsan T, Sosna O. Midterm clinical and first reproductive results of a randomized controlled trial comparing uterine fibroid embolization and myomectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mara M, Maskova J, Fucikova Z, Kuzel D, Belsan T, Sosna O. Uterine artery embolization versus laparoscopic uterine artery occlusion: The outcomes of a prospective, nonrandomized clinical trial. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:1041–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0388-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CC, Lee MH. Transcatheter arterial embolotherapy: A therapeutic alternative in obstetrics and gynecologic emergencies. Semin Interv Radiol. 2006;23:240–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thabet A, Kalva SP, Liu B, Mueller PR, Lee SI. Interventional radiology in pregnancy complications: Indications, technique, and methods for minimizing radiation exposure. Radiographics. 2012;32:255–74. doi: 10.1148/rg.321115064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghai S, Rajan DK, Asch MR, Muradali D, Simons ME, TerBrugge KG. Efficacy of embolization in traumatic uterine vascular malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol JVIR. 2003;14:1401–8. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000096761.74047.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grivell RM, Reid KM, Mellor A. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: A review of the current literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:761–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000183684.67656.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popovic M, Puchner S, Berzaczy D, Lammer J, Bucek RA. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of adenomyosis: A review. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:901–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita Y, Harada M, Yamamoto H, Miyazaki T, Takahashi M, Miyazaki K, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization of obstetric and gynaecological bleeding: Efficacy and clinical outcome. Br J Radiol. 1994;67:530–4. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-67-798-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mihmanli I, Cantasdemir M, Kantarci F, Halit Yilmaz M, Numan F, et al. Percutaneous embolization in the management of intractable vaginal bleeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;264:211–4. doi: 10.1007/s004040000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moodley M, Moodley J. Transcatheter angiographic embolization for the control of massive pelvic hemorrhage due to gestational trophoblastic disease: A case series and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:94–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehaeck CM. Transcatheter embolization of pelvic vessels to stop intractable hemorrhage. Gynecol Oncol. 1986;24:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(86)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert L, Porter W, Brown VA. Postpartum haemorrhage-a continuing problem. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirby JM, Kachura JR, Rajan DK, Sniderman KW, Simons ME, Windrim RC, et al. Arterial embolization for primary postpartum hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1036–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonsalves M, Belli A. The role of interventional radiology in obstetric hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:887–95. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ornan D, White R, Pollak J, Tal M. Pelvic embolization for intractable postpartum hemorrhage: Long-term follow-up and implications for fertility. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:904–10. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vedantham S, Goodwin SC, McLucas B, Mohr G. Uterine artery embolization: An underused method of controlling pelvic hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:938–48. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deux JF, Bazot M, Le Blanche AF, Tassart M, Khalil A, Berkane N, et al. Is selective embolization of uterine arteries a safe alternative to hysterectomy in patients with postpartum hemorrhage? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:145–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doumouchtsis SK, Papageorghiou AT, Arulkumaran S. Systematic review of conservative management of postpartum hemorrhage: What to do when medical treatment fails. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:540–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000271137.81361.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morison JE. Placenta accreta. A clinicopathologic review of 67 cases. Obstet Gynecol Annu. 1978;7:107–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diop AN, Chabrot P, Bertrand A, Constantin JM, Cassagnes L, Storme B, et al. Placenta accreta: Management with uterine artery embolization in 17 cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:644–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu PC, Ou HY, Tsang LLC, Kung FT, Hsu TY, Cheng YF. Prophylactic intraoperative uterine artery embolization to control hemorrhage in abnormal placentation during late gestation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1951–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivan E, Spira M, Achiron R, Rimon U, Golan G, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. Prophylactic pelvic artery catheterization and embolization in women with placenta accreta: Can it prevent cesarean hysterectomy? Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:455–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banovac F, Lin R, Shah D, White A, Pelage JP, Spies J. Angiographic and interventional options in obstetric and gynecologic emergencies. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:599–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zakaria MA, Abdallah ME, Shavell VI, Berman JM, Diamond MP, Kmak DC. Conservative management of cervical ectopic pregnancy: Utility of uterine artery embolization. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:872–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirakawa M, Tajima T, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Ishigami K, Yahata H, et al. Uterine artery embolization along with the administration of methotrexate for cervical ectopic pregnancy: Technical and clinical outcomes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1601–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trambert JJ, Einstein MH, Banks E, Frost A, Goldberg GL. Uterine artery embolization in the management of vaginal bleeding from cervical pregnancy: A case series. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:844–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frates MC, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, Di Salvo DN, Brown DL, Laing FC, et al. Cervical ectopic pregnancy: Results of conservative treatment. Radiology. 1994;191:773–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.3.8184062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]