Abstract

Tyrosine phosphorylation of membrane receptors and scaffold proteins followed by recruitment of SH2 domain-containing adaptor proteins constitutes a central mechanism of intracellular signal transduction. During early T-cell receptor (TCR) activation, phosphorylation of Linker for Activation of T cells (LAT) leading to recruitment of adaptor proteins, including Grb2, is one prototypical example. LAT contains multiple modifiable sites and this multivalency may provide additional layers of regulation, although this is not well understood. Here, we quantitatively analyze the effects of multivalent phosphorylation of LAT by reconstituting the initial reactions of the TCR signaling pathway on supported membranes. Results from a series of LAT constructs with combinatorial mutations of tyrosine residues reveal a previously unidentified allosteric mechanism in which the binding affinity of LAT:Grb2 depends on the phosphorylation at remote tyrosine sites. Additionally, we find that LAT:Grb2 binding affinity is altered by membrane localization. This allostery mainly regulates the kinetic on-rate, not off-rate, of LAT:Grb2 interactions. LAT is an intrinsically disordered protein and these data suggest that phosphorylation changes the overall ensemble of configurations to modulate the accessibility of other phosphorylated sites to Grb2. Using Grb2 as a phosphorylation reporter, we further monitored LAT phosphorylation by TCR ζ chain-recruited ZAP-70, which suggests a weakly processive catalysis on membranes. Taken together, these results suggest that signal transmission through LAT is strongly gated and requires multiple phosphorylation events before efficient signal transmission is achieved.

Keywords: signal transduction, multivalency, allostery, phosphorylation, supported lipid bilayer

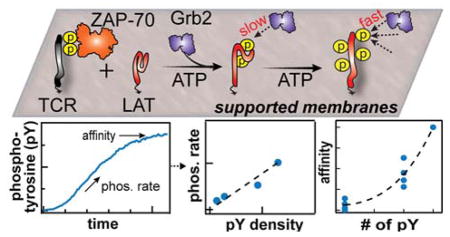

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tyrosine phosphorylation plays a central role in intracellular signal transduction 1–4. There are numerous examples of signaling molecules in which phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues (Y) leads to functional alterations (e.g. activating or deactivating) by modulating the structure of the folded proteins 5. Alternatively, phosphorylated tyrosine residues can function as recruitment sites for other signaling proteins that contain SH2 domains. In the case of T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling (Fig. 1A), engagement of the TCR with agonist ligand leads to phosphorylation of multiple tyrosine residues on the cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of the TCR. The kinase ZAP-70 is then recruited to these phosphotyrosine (pY) sites where it is phosphorylated at sites Y315, Y319 and Y493 by the Src family kinase Lck 6,7. Phosphorylation of ZAP-70 at these residues releases autoinhibition, enabling ZAP70 to phosphorylate tyrosine sites on LAT 1,4. LAT, like other receptor signaling scaffolds including EGFR, nephrin, and PD-1, has multiple phosphorylatable tyrosine sites that recruit downstream SH2-domain adaptor proteins such as Grb2, Gads, and PLCγ 1–4,8–11. Transmission of signals depends on the phosphorylation and recruitment events at these sites. Furthermore, multivalency creates opportunities for additional regulatory controls, which are only now beginning to be appreciated. For instance, recent observations in LAT:Grb2:SOS 12–15 and nephrin:Nck:N-WASP 16,17 reveal the formation of extended multimolecular assemblies in response to multivalent phosphorylation. These assemblies can even exhibit gelation phase transitions driven by tyrosine phosphorylation, which may govern downstream signal transmission, amplification, and noise suppression.

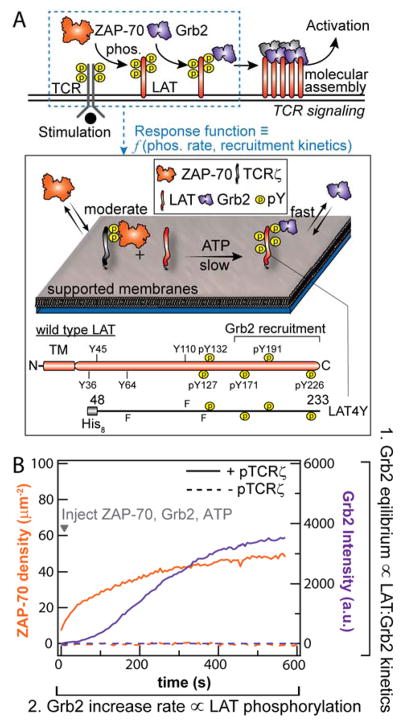

Figure 1. Membrane reconstitution of LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70.

(A) Biochemical reconstitution of LAT phosphorylation by TCR ζ chain-recruited ZAP-70 on supported membranes. LAT and phosphorylated TCR ζ chain are tethered onto fluid bilayers. ZAP-70, Grb2, and ATP are injected into the solution to initiate and monitor phosphorylation of LAT. The LAT construct used in this experiment is shown in the lower panel. TM, Y and F denote the transmembrane domain, tyrosine residue, and phenylalanine, respectively. The tyrosines that have been observed to be phosphorylated during signal activation are denoted with a letter “p”. The LAT4Y construct preserves the four distal tyrosines with three other tyrosines mutated to phenylalanine. (B) Simultaneous imaging of ZAP-70-Alexa Fluor 488 and Grb2-Alexa Fluor 647 during phosphorylation. The initial increase and final equilibrium phase of Grb2 reflects LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70 and LAT:Grb2 affinity, respectively.

In this study, we characterize the phosphorylation rates of multivalent LAT and subsequent adaptor protein binding kinetics on supported membranes (Fig. 1A). Using this two-dimensional enzymatic assay, we discovered a previously unidentified allosteric mechanism in which the binding kinetics of LAT:Grb2 depend nonlinearly on the number of pY residues on LAT. Specifically, these results indicate that LAT:Grb2 binding at one pY site is favorably altered by the phosphorylation of remote tyrosine sites. Although this effect can be described as allosteric modulation (i.e. action at a distance), it fundamentally differs from classical allostery (in which remote effects on binding are achieved through ligand-binding induced changes in the folded protein structure) 18,19 since LAT is an intrinsically disordered protein. Measurements described here indicate that allosteric regulation is primarily manifested in the kinetic on-rates of LAT:Grb2 interactions. This suggests that phosphorylation of LAT at remote sites changes the overall ensemble of LAT configurations, rendering other pY sites more accessible to Grb2 binding. We also found that LAT phosphorylation by membrane-recruited ZAP-70 is weakly processive using Grb2 as the phosphotyrosine reporter. Collectively, these observations suggest that signal transmission through LAT is suppressed for weak signals, but amplified for a strong input that successfully leads to multiple phosphorylation of LAT. Furthermore, quantitative values of the molecular parameters measured here depend on membrane localization, underscoring the importance of reconstitution in a membrane format.

Results

In vitro membrane reconstitution of LAT phosphorylation by TCR ζ chain –recruited ZAP-70

Here we introduce a two-dimensional enzymatic assay on a supported membrane platform to quantitatively characterize the phosphorylation of LAT by TCR ζ chain-recruited ZAP-70 and Grb2 recruitment in real time (Fig. 1A). Pre-phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of TCR ζ chain (pTCR) and fluorescently labeled LAT-Alexa Fluor 568 (referred to as LAT) were chelated onto DOPC bilayers containing 4% NiNTA-modified lipids via N-terminal His8-tags (Fig. 1A)20. LAT contains nine tyrosine residues and Grb2 binds to the three most distal tyrosine residues (Y171, Y191, and Y226), while a fourth tyrosine residue (Y132) is bound by PLCγ1 8,21. In these studies, we utilize an engineered LAT construct (residue 48-233) containing only these four tyrosine residues (LAT4Y) to systematically quantify the effects of multivalent tyrosine phosphorylation on Grb2 recruitment; other tyrosine residues were mutated to phenylalanine (F) (Fig. 1). This LAT construct and the mutation strategy follows prior work on LAT 8,15. The binding affinities of LAT4Y to Grb2 are later compared to those of LAT mutants containing single or triple tyrosine residues in systematic permutations (Table S1, S2). The densities of laterally fluid LAT can be controlled from 50 to 3000 molecule/μm2 and can be accurately measured using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) (Fig. S1). For comparison, physiological densities of LAT are 100 - 1000 molecule/μm2 22. Although not addressed in the experiments described here, this system is amenable to further elaboration of membrane lipid and protein context to explore these additional dimensions of the system.

The reconstituted assay was optimized for the following kinetic considerations to resolve LAT phosphorylation: i) Grb2 binds the pY rapidly (< 1 s) to report accurately on the kinetics of phosphorylation, ii) ZAP-70 is recruited to membranes by TCR ζ chain, at a moderate rate (~60 s), and iii) phosphorylation of LAT by ZAP-70 occurs over a longer time period (~10 min) (Fig. 1B). (i) and (ii) are achieved by tuning the protein concentration such that they are fundamentally limited by the off rate of ligand-receptor binding kinetics. While accumulation of membrane-associated ZAP-70 during T-cell activation can be higher, we use low amounts of the protein in these reconstitution experiments to temporally resolve LAT phosphorylation; the rate constants extracted here are general and can be used to extrapolate phosphorylation rate to different protein concentrations. The conditions that allowed LAT phosphorylation to be resolved were satisfied when 500 pM ZAP-70-SNAP-Alexa Fluor 488 (referred to as ZAP-70), 50 nM Grb2-Alexa Fluor 647 (referred to as Grb2) and ATP were injected onto bilayers containing ~500 molecule/μm2 TCR ζ chain and 50–2000 molecule/μm2 LAT (Fig. 1B). Membrane-localized ZAP-70 was primarily responsible for LAT phosphorylation; ZAP-70 in solution (in experiments without TCR ζ chain) negligibly phosphorylated LAT (Fig. 1B, dashed traces). The ZAP-70 used in these experiments was incubated with ATP prior to the experiment for over an hour to relieve its autoinhibition by phosphorylating Y315, Y319, Y493; a similar phosphorylation rate of LAT was obtained for ZAP-70 pre-incubated with Src kinase domain.

Real-time monitoring of LAT phosphorylation was accomplished with simultaneous imaging of membrane-associated ZAP-70 and Grb2, measured by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Importantly, in these experiments, Grb2 acted as a phosphorylation sensor by stochastically and rapidly sampling the pY on membrane surfaces (< 1 s) without saturating pY in individual LAT molecules, i.e. each LAT4Y has, on average, much less than one Grb2 bound (Fig. S2). The SH2 domain of Grb2 bound to pY residues on LAT with fast (~100 ms) off-rates and established a steady state during LAT phosphorylation14. A typical phosphorylation trace of Grb2 fluorescent intensity consisted of two phases: i) the increase in Grb2 fluorescent intensity reflecting LAT phosphorylation by membrane-associated ZAP-70 and, ii) the plateau of Grb2 fluorescent intensity reflecting the affinities between Grb2 and fully phosphorylated LAT(Fig. 1B). Since the phosphorylation readout itself is coupled with the binding affinity of LAT:Grb2, we first quantified the thermodynamics and kinetics of LAT:Grb2 binding.

Allostery in the LAT:Grb2 binding kinetics

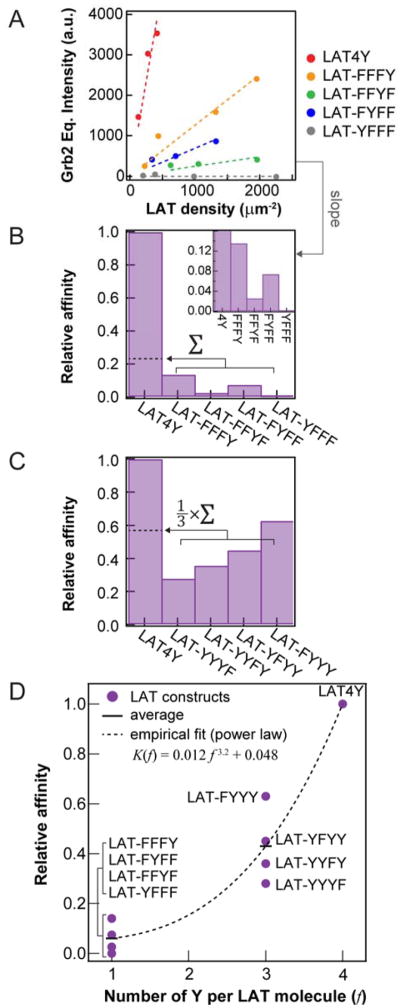

Previous measurements of pLAT:Grb2 affinities were performed using solution-based isothermal calorimetry (ITC) with phosphorylated peptides of LAT that contained single tyrosine residues 8. Therefore, we first compared the binding affinities of our engineered LAT4Y in which we systematically mutated three of the four tyrosine residues to phenylalanine (Y to F) (monovalent LAT constructs are referred to as LAT1Y) using ITC (Table S1). LAT was phosphorylated in solution prior to ITC experiments and analyzed by mass spectrometry to determine the degree of phosphorylation. We use a four letter code to denote the tyrosine sequence positions of LAT, Y132, Y171, Y191 and Y226, with either Y or F at each position; e.g. LAT-FFYF is LAT-F132-F171-Y191-F226. ITC measurements of LAT-YFFF, LAT-FYFF, LAT-FFYF, or LAT-FFFY binding to Grb2 showed a similar trend ( : LAT-FFYF:Grb2 > LAT-FYFF:Grb2 ≈ LAT-FFFY:Grb2) to previous peptide studies 8. As with previous studies, pY132 of LAT did not detectably bind Grb2. These solution-based ITC experiments assessed the binding properties of LAT1Y:Grb2 determined by the sequence and conformational accessibility in three-dimensions.

Next, we quantified the affinities of each LAT:Grb2 pair on supported membranes. The equilibrium of Grb2 recruitment (i.e. the amount of Grb2 recruited to fully phosphorylated LAT) reflects the effective binding affinity between a LAT molecule and Grb2 (Fig. 1B). In the case of LAT1Y, this affinity is well defined to be a single pY:Grb2 interaction; in the case of LAT4Y, the affinity is an effective affinity of three Y sites interacting with Grb2. The result yielded two unexpected observations (Fig. 2A). First, the affinity trend of LAT1Y:Grb2 on membranes is reversed when compared with the solution-based ITC binding results ( : LAT-FFYF:Grb2 < LAT-FYFF:Grb2 < LAT-FFFY:Grb2) (Fig. 2B). Single-molecule dwell time analysis indicates that both the kinetic on- and off-rates modulate the affinities of LAT1Y:Grb2 on membranes (Fig. 3). The relative on-rates for LAT-FFYF:Grb2, LAT-FYFF:Grb2, LAT-FFFY:Grb2 are 0.45:1.25:1, estimated from and the off rate (the relative off-rates for LAT-FFYF:Grb2, LAT-FYFF:Grb2, LAT-FFFY:Grb2 are 2.4:2.4:1).

Figure 2. Deconstructing the multivalent contributions to LAT:Grb2 binding kinetics.

(A) Grb2 equilibrium from LAT density titration. The slope is proportional to the binding affinity. (B) Comparison of the relative affinities between monovalent LAT constructs and Grb2, calculated from the slopes in (A). (C) The relative affinities between trivalent LAT and Grb2. (D) Summary of (B) and (C). The empirical fit through the averages of affinities is a power law. The implications of power-law fitting are discussed in SI Text.

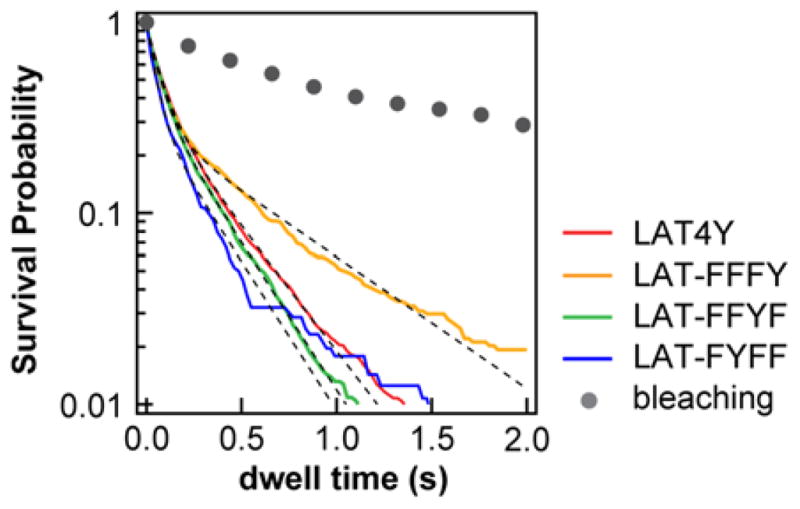

Figure 3. Single-molecule dwell time analysis of LAT:Grb2.

The survival probability distributions from single-molecule tracking of membrane-recruited Grb2-Alexa Fluor 647. Bleaching curve (grey) is measured by photobleaching immobilized Grb2 on a glass substrate. After correction of the bleaching rates (SI Methods), the off rates are estimated to be 2.8, 1.4, 3.3, 3.4 s−1 for LAT4Y:Grb2, LAT-FFFY:Grb2, LAT-FFYF:Grb2 and LAT-FYFF:Grb2, respectively.

The second unexpected observation is that the affinity of LAT4Y:Grb2 cannot be linearly reconstructed by summing the four LAT1Y:Grb2 affinities. This simple linear summation would be expected if the pY sites were independent of each other. However, we observed that fully phosphorylated LAT4Y has a 4–5 fold enhanced affinity for Grb2 as compared with the linear sum of affinities of all LAT1Y:Grb2 binding interactions (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the amount of recruited Grb2 is small compared to LAT densities in this assay, such that a LAT4Y molecule only binds to one Grb2 molecule or less, on average (Fig. S2). The affinity modulation we observe here thus results from the presence of pY at a remote site, not multiple Grb2 molecules binding to a single LAT4Y. This observation is also independent of LAT density (linear slope in Fig. 2A), therefore it is not mediated by other LAT molecules on membrane surfaces.

To validate the allosteric hypothesis, we compared the affinities of LAT4Y:Grb2 with the affinities of LAT3Y (trivalent LAT):Grb2 by systematically mutating a single tyrosine residue to phenylalanine (i.e. LAT-FYYY, LAT-YFYY, LAT-YYFY, and LAT-YYYF) (Table S1). Consistently, linear addition of the affinities of LAT3Y:Grb2 (divided by 3 to account for the 3 pY sites in each LAT3Y) rescued only about half the affinity of LAT4Y:Grb2, although LAT3Y recapitulated the LAT4Y:Grb2 affinity closer than LAT1Y. Most notably, mutation of Y132 (LAT-FYYY), which does not bind to Grb2 (Fig. 2B, LAT-YFFF) resulted in a decreased apparent affinity for Grb2 (Fig. 2C, LAT-FYYY). Allosteric regulation of LAT:Grb2 binding is summarized in Fig. 2D. Based on the empirical fitting (Fig. 2D), the effective allosteric interactions between pY residues increased approximately linearly with the number of phosphotyrosines (SI Text, Fig. S3). Finally, dwell time analysis indicated that the off rate of LAT4Y:Grb2 is roughly the average of that for the individual LAT1Y:Grb2 interactions (Fig. 3). More importantly, the measured similarity in the off rates suggests that this allosteric effect on binding is mediated through the kinetic on-rates of LAT:Grb2 interactions. This is particularly intriguing since LAT is known to be unstructured. To ensure that these observations were not the result of a difference in the photophysics of the dyes, we determined that the Alexa Fluor dyes used to label LAT exhibit almost identical photophysics across all LAT constructs, as characterized by brightness analysis from FCS and fluorescent lifetime analysis from time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) (Fig. S3). Therefore, the observed nonlinear addition of Grb2 recruitment most likely reflects a genuine molecular binding property.

LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70 is weakly processive

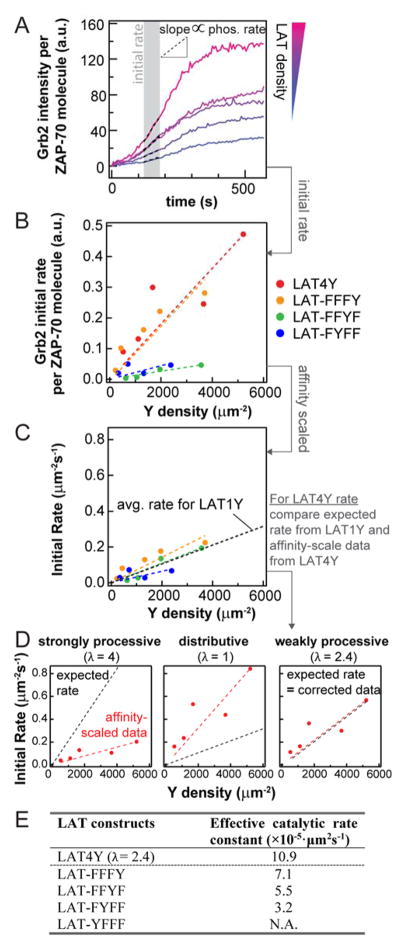

With quantitative characterization of LAT:Grb2 interactions, we then used Grb2 as a molecular sensor to probe LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70 in real time. Effective phosphorylation rate constants were obtained by simultaneously imaging ZAP-70 and Grb2 membrane recruitment across different LAT densities (Fig. 4A). To account for the protein copy number of recruited ZAP-70 (which changes over time), the Grb2 intensity profiles were analyzed according to the following equation:

| Eq. [1] |

where v is the initial rate of phosphorylation, E is the ZAP-70 density on membranes, and P is the pLAT density inferred from Grb2 recruitment. For simple solution Michaelis–Menten kinetics, where kcat is the catalytic rate and KM is the Michaelis constant. However, the analysis performed here is slightly different from solution-based kinetic measurements, in the sense that the functional, or membrane-recruited, enzyme copy number increases over time (i.e. E(t)). The initial rates for phosphorylation of LAT4Y and LAT1Y are summarized in Fig. 4B. The conversion of Grb2 intensities to pLAT densities (by dividing by KA values) provided the necessary calibration for expressing the catalytic rate constants in proper 2D units (Fig. 2A, 4C). We calculated phosphorylation rate constants for LAT1Y to be about 5×10−5 μm2s−1 (Fig. 4C, E). The initial rates in these cases are approximately linear; suggesting that phosphorylation on membranes is near a diffusion-limited regime. Rate constants calculated from this assay encompass the surface effect of membranes, which is reflected in the 2D units without ambiguity.

Figure 4. Phosphorylation rates of LAT by ZAP-70.

(A) The apparent initial rates are obtained by linear fitting of Grb2 intensity from LAT density titrations. (B) The apparent initial rates from traces shown in (A). (C) The effective catalytic rates in 2D units, after correction for affinity (Fig. 2D). (D) In the case of affinity correction for LAT4Y, an assumption of the degree of processivity is required to convert Grb2 recruitment to pY production. The assumption that was used was benchmarked with average catalytic rate of LAT1Y. Only in the case of weak processivity does the expected rate from LAT1Y converge with the converted data (right); both strongly processive and purely distributive mechanisms are not consistent with the expectation from LAT1Y data. The red and black line are the converted data and expected data of LAT4Y phosphorylation, respectively. (E) Summary of the effective rate constants from (C)(D).

For the case of LAT4Y phosphorylation, conversion of Grb2 readout to pLAT requires an assumption of the phosphorylation dynamics because Grb2 recruitment depends on the valency of pY: whether phosphorylation is processive or distributive will result in the binding of different numbers of Grb2 molecules to a single LAT4Y, even for the same phosphorylation rate. Processive catalysis is a modification mechanism in which multiple phosphorylation events occur in a single encounter between the enzyme and its substrate 23. It has been speculated that kinases or phosphatases in the TCR activation pathway exhibit processivity due to the prevalence of multivalent substrates. Experimental verification of a processive mechanism is compounded by the fact that processivity is intimately related to the diffusion of the interacting molecules 24. In our reconstitution experiments, the type of phosphorylation mechanism will affect reconstruction of the phosphorylation rate constants for LAT4Y since the conversion of Grb2 readout to pY densities depends on the binding kinetics, which is not additive due to allosteric effects. However, the type of assumption used in the analysis can be compared with the expected rates from LAT1Y, e.g. strong processivity will result in an increase in phosphorylation rate for LAT4Y when compared to that of LAT1Y of the same Y density. This argument provides the following self-consistency analysis (see SI Methods and Materials), with the LAT1Y as a benchmark that can be informative:

| Eq. [2] |

where the left-hand side is the data from LAT4Y measurement after correction of the affinities, the right-hand side is the expected catalytic rate of LAT4Y estimated from the average phosphorylation of LAT1Y, λ is the degree of processivity, ranging from 1–4 in the case of LAT4Y, and 〈·〉 denotes average. The left-hand side and the right-hand side of Eq. [2] will only be equal if the reconstructed rate matches the expected rates, i.e. λ is self-consistent. In our reconstitution experiments, only a weakly processive mechanism (λ = 2.4) satisfies this self-consistency, both purely distributive (λ = 1) and strongly processive (λ = 4) mechanisms are not self-consistent (Fig. 4D). Therefore, this analysis suggests that LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70 on membranes is weakly processive.

Discussion

Signal initiation at LAT is modulated by the phosphorylation rate and subsequent recruitment of adaptor proteins from the cytosol. On a supported membrane assay, we observed that the phosphorylation of LAT by ZAP-70 recruited to pTCR is weakly processive, and that the binding kinetics of LAT:Grb2 was enhanced with an increasing degree of phosphorylation by a form of allosteric regulation. The allostery of LAT is especially interesting because LAT has been thought to be intrinsically disordered. Since phosphorylation results in significant introduction of negative charge, it is tempting to suspect a molecular mechanism for the observed allostery based on electrostatic effects. However, such electrostatic forces are substantially screened in the aqueous environment of the cytosol (Debye length ~ 0.6 nm) 25, and are thus not expected to exert significant effects much beyond 1 nm. The shortest distance between the tyrosine residues in LAT4Y is 5–10 nm for the fully extended protein; long-range electrostatic effects are expected to be minimal. On the other hand it has been shown that, in the case of intrinsically disordered proteins, the hydrodynamic radius increases with increasing net charge per residue 26,27. LAT is a highly negatively charged protein; the cytoplasmic domain (residue 30-233) of LAT has a net charge of −22 at pH 7.0. Therefore, increasing the number of pY in LAT may lead to a relatively expanded structure with better accessibility for Grb2 interactions (Fig. S5). This is consistent with the observation that the binding affinities of LAT:Grb2 increase with increasing number of pY, offering support to the hypothesis that the conformational ensembles of LAT are altered by the degree of pY.

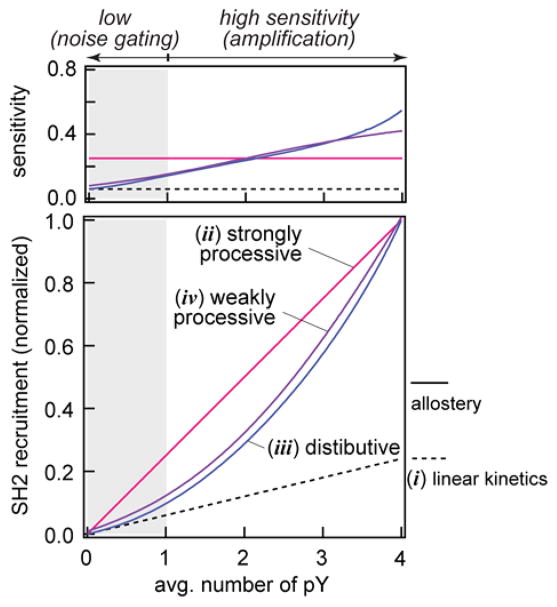

This type of allosteric regulation may provide an additional layer of control over signal initiation through LAT, depending on the phosphorylation mechanism of LAT by ZAP-70. Here we discuss the possible signaling consequence of these potential molecular regulations. At a basic level, signal propagation can be quantitatively described by an input-response function that relates the efficiency of a signal input to its output. In the case of LAT, the input-response function can be defined as the number of membrane-associated SH2 molecules as a function of pY fraction. Recruited Grb2 density is then xpLAT:Grb2 = K(f)[Grb2]xpLAT, where xi is the density of molecular species i on membranes and K(f) is the LAT:Grb2 affinity, given that Grb2 rapidly responds to pY. Using the empirical characterization of LAT:Grb2 binding kinetics (Fig. 2D, SI Methods and Materials), we estimated the response function under four different scenarios: i) non-allosteric (linear) pY:Grb2 binding kinetics (i.e. binding at a given site is independent of phosphorylation status at other sites) where the response function is not affected by the phosphorylation mechanism, ii) allostery in binding kinetics coupled with strongly processive phosphorylation (λ = 4), iii) allostery in binding kinetics coupled with distributive phosphorylation (λ = 1), and iv) allostery in binding kinetics coupled with weakly processive phosphorylation (λ = 2) (Fig. 5). For each scenario, we calculated the sensitivity of the input-response function, defined as the number of SH2 recruitment per unit of phosphorylation events (dxpLAT:Grb2/dxpY). While both (i) and (ii) result in a constant sensitivity to the number of phosphorylation events (Fig. 5), the response function exhibits regions of different sensitivities to the same amount of pY when allostery is coupled to a distributive mechanism (case (iii)). Interestingly, the response function of weakly processive phosphorylation (iv) resembles a distributive mechanism, since the affinity enhancement from 2pY to 4pY is substantial. The feature of exhibiting low sensitivities at low phosphorylation levels and high sensitivities at high phosphorylation levels suggests a dual role of noise gating and signal amplification in LAT signaling. This can be especially consequential when the reactions are under the pressure of phosphatases in living cells.

Figure 5. Response function of LAT phosphorylation.

The response function through LAT is calculated based on the empirical characterization of LAT recruitment kinetics measured from this study. The sensitivity of signal response (top panel) is the first derivative of SH2 recruitment (lower panel).

Efficient suppression of noise and amplification of signals can be beneficial, particularly considering that the TCR can detect agonists at the single-molecule level 28. In addition, the ability to gate noise can be important to LAT signaling because multiple mechanisms of signal amplification occur downstream of LAT phosphorylation. Other than the observed enhancement of on rates by LAT allostery, the dwell times of Grb2 and downstream proteins are extended by LAT:Grb2:SOS assemblies when LAT is substantially phosphorylated 14,15. These events eventually lead to further downstream amplification steps such as positive feedback of SOS:Ras interactions 29,30. Taken together, signaling through LAT possibly involves at least two sequential amplification mechanisms in which signaling initiation is safeguarded for low signal inputs (Fig. S6). Without a gating mechanism, basal phosphorylation may be equally amplified resulting in frequent erroneous signaling events. Interestingly, these mechanisms are all modulated by the degree of multivalency, highlighting its role in signal transduction.

In conclusion, we established a two-dimensional enzymatic assay to quantify the response dynamics of signaling through LAT. The allostery reflected in the binding kinetics depends on the degree of multivalency, revealing an additional layer of control by multivalent signaling proteins. This quantitative assay can be used to evaluate the dynamics of other membrane-localized signaling pathways, such as recently reconstituted phosphoinosititide-3-kinase (PI3K) regulatory pathway 31, Src family kinases 14–16, phosphatases 15, or other pathways that transmit signals by the regulation of multivalent modifications in signal transduction.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Solution-based isothermal titration calorimetry of monovalent LAT1Y:Grb2

| LAT1Y Variant | KD (nM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | ΔS (kcal/mol•K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAT FFFY | 458.9 (320, 668) | −13.8 (−15.22, −12.67) | −18.1 |

| LAT FFYF | 195.0 (134, 281) | −15.0 (−16.36, −13.91) | −20.5 |

| LAT FYFF | 462.9 (331, 669) | −15.0 (−16.31, −13.77) | −22.0 |

| LAT YFFF | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

The numbers in parenthesis denote the standard deviation for each set of measurements.

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by National Institute of Health P01 (AI091580 to J.T.G.) Additional support was provided by an HHMI Collaborative Innovator Award, NIH (R01-056322 to M.K.R.) and the Welch Foundation (I-1544 to M.K.R.). J.A.D. was supported by National Research Service Award F32 (5-F32-DK101188). We thank Chad Brautigam and Shih-Chia Tso at the UTSW Macromolecular Biophysics Resource for assistance with ITC, David S. King at the HHMI for measurements with mass spectrometry, and Enfu Hui at University of California San Diego for providing the TCR ζ and ZAP-70 vectors. We thank Jean Chung and other members in Jay Groves and Michael Rosen laboratory for helpful discussion. We thank Neel Shah and John Kuriyan for insightful comments on the molecular mechanism of LAT allostery.

Footnotes

Further discussion of Fig. 2D; detailed methods; detailed characterization of supported membranes and schematic of models; list of constructs

References

- 1.Samelson LE. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.092601.111357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Good MC, Zalatan JG, Lim WA. Science. 2011;332:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1198701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott JD, Pawson T. Science. 2009;326:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1175668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balagopalan L, Coussens NP, Sherman E, Samelson LE, Sommers CL. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2010:2. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boggon TJ, Eck MJ. Oncogene. 2004;23:7918–7927. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deindl S, Kadlecek TA, Brdicka T, Cao XX, Weiss A, Kuriyan J. Cell. 2007;129:735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Q, Barros T, Visperas PR, Deindl S, Kadlecek TA, Weiss A, Kuriyan J. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2188–201. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01637-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houtman JCD, Higashimoto Y, Dimasi N, Cho SW, Yamaguchi H, Bowden B, Regan C, Malchiodi EL, Mariuzza R, Schuck P, Appella E, Samelson LE. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4170–4178. doi: 10.1021/bi0357311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlessinger J. Cell. 2000;103:211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frischknecht F, Moreau V, Rottger S, Gonfloni S, Reckmann I, Superti-Furga G, Way M. Nature. 1999;401:926–929. doi: 10.1038/44860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones N, Blasutig IM, Eremina V, Ruston JM, Bladt F, Li HP, Huang HM, Larose L, Li SSC, Takano T, Quaggin SE, Pawson T. Nature. 2006;440:818–823. doi: 10.1038/nature04662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nag A, Monine MI, Faeder JR, Goldstein B. Biophys J. 2009;96:2604–2623. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houtman JCD, Yamaguchi H, Barda-Saad M, Braiman A, Bowden B, Appella E, Schuck P, Samelson LE. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:798–805. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WYC, Yan Q, Lin WC, Chung J, Hansen SD, Christensen SM, Tu HL, Kuriyan J, Groves JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8218–8223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602602113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su X, Ditlev JA, Hui EF, Xing WM, Banjade S, Okrut J, King DS, Taunton J, Rosen MK, Vale RD. Science. 2016;352:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banjade S, Rosen MK. eLife. 2014;3:e04123. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li P, Banjade S, Cheng HC, Kim S, Chen B, Guo L, Llaguno M, Hollingsworth JV, King DS, Banani SF, Russo PS, Jiang QX, Nixon BT, Rosen MK. Nature. 2012;483:336–U129. doi: 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dill KA, Bromberg S. Molecular Driving Force. 2. Garland Science; New York, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuriyan J, Konforti B, Wemmer D. The Molecules of Life. Garland Science; New Yorkm USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nye JA, Groves JT. Langmuir. 2008;24:4145–4149. doi: 10.1021/la703788h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu M, Janssen E, Zhang W. J Immunol. 2003;170:325–333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson DJ, Owen DM, Rossy J, Magenau A, Wehrmann M, Gooding JJ, Gaus K. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:655–U214. doi: 10.1038/ni.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patwardhan P, Miller WT. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2218–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopich IV, Szabo A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19784–19789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319943110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safran SA. Statistical thermodynamics of surfaces, interfaces, and membranes. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; U.S.A: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao AH, Crick SL, Vitalis A, Chicoine CL, Pappu RV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8183–8188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911107107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Proteins. 2000;41:415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donoghue GP, Pielak RM, Smoligovets AA, Lin JJ, Groves JT. eLife. 2013;2:e00778. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das J, Ho M, Zikherman J, Govern C, Yang M, Weiss A, Chakraborty AK, Roose JP. Cell. 2009;136:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iversen L, Tu HL, Lin WC, Christensen SM, Abel SM, Iwig J, Wu HJ, Gureasko J, Rhodes C, Petit RS, Hansen SD, Thill P, Yu CH, Stamou D, Chakraborty AK, Kuriyan J, Groves JT. Science. 2014;345:50–54. doi: 10.1126/science.1250373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziemba BP, Burke JE, Masson G, Williams RL, Falke JJ. Biophys J. 2016;110:1811–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.