Abstract

Objective

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. This post hoc analysis evaluated patients receiving tofacitinib monotherapy or combination therapy, as well as those who switched from monotherapy to combination therapy (mono→combo) or vice versa (combo→mono) in long-term extension (LTE) studies.

Methods

Data were pooled from open-label LTE studies (ORAL Sequel (NCT00413699; ongoing; data collected 14 January 2016) and NCT00661661) involving patients who participated in qualifying index studies. Efficacy outcomes included American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70 rates, change from baseline in Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-4(ESR)), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index and DAS28-4(ESR) and CDAI low disease activity and remission. Safety was evaluated over 96 months.

Results

Of the 4967 patients treated, 35.4% initiated tofacitinib monotherapy, 64.6% initiated combination therapy, 2.6% were mono→combo switchers and 7.1% were combo→mono switchers. Patients who switched multiple times were excluded. Of those who initiated monotherapy and combination therapy, 87.8% (1543/1757) and 82.0% (2631/3210), respectively, remained on the same regimen throughout the study; efficacy was maintained. Incidence rates (IRs) for serious adverse events with tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, were 9.42 and 8.41 with monotherapy and 8.36 and 10.75 with combination therapy; IRs for discontinuations due to AEs were 7.13 and 6.06 with monotherapy and 7.82 and 8.06 with combination therapy (overlapping CIs). For mono→combo and combo→mono switchers, discontinuations due to AEs were experienced by 0.8% and 0.9%, respectively, within 30 days of switching.

Conclusion

Tofacitinib efficacy as monotherapy or combination therapy was maintained through month 48 and sustained to month 72, with minimal switching of treatment regimens. Safety was consistent over 96 months.

Clinical trial registration

NCT00413699 (Pre-results) and NCT00661661 (Results).

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, disease activity, treatment

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy were assessed in two long-term extension (LTE) studies, which are part of one of the largest clinical development programmes in RA to date.

What does this study add?

Tofacitinib maintained long-term efficacy over 6 years and demonstrated consistent safety when administered as either monotherapy or with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs).

A small proportion of patients who received tofacitinib monotherapy added csDMARDs during the LTE studies.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

These results show that tofacitinib can maintain long-term efficacy and safety as monotherapy or with background csDMARDs, with minimal switching between treatment regimens.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a debilitating autoimmune disease characterised by chronic inflammation with subsequent destruction of the joints and surrounding tissues of the musculoskeletal system.1 2 As RA imposes a significant health burden, optimum treatment management is important in an effort to prevent disease progression and improve long-term patient function.

Currently, the goal of RA treatment is to achieve remission, or at least a state of low disease activity (LDA) in those patients in whom remission cannot be achieved. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism both recommend that patients are initially treated with conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate (MTX), due to their low cost and established efficacy.3 4 If csDMARDs are not effective, the guidelines recommend the addition of a biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), such as a tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), or a targeted synthetic DMARD, such as tofacitinib, as these have been shown to improve clinical outcomes.4–13

Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor for the treatment of RA, has demonstrated efficacy and safety as monotherapy and in combination therapy with background MTX in phase 2 and phase 3 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) ranging from 6 to 24 months’ duration.14–23 Although double-blind RCTs represent the gold standard in determining the short-term efficacy and safety of therapies, agents used to treat chronic conditions such as RA must also demonstrate long-term effectiveness and safety. Moreover, the reporting of long-term clinical outcomes should better enable clinicians to set realistic expectations of likely long-term treatment efficacy.24 For this reason, two open-label, long-term extension (LTE) studies (A3921024 and A3921041) of tofacitinib were conducted, which included patients with RA who participated in qualifying phase 1, 2 and 3 studies.25 26

Here, we report pooled data from a post hoc analysis of these LTE studies. We describe long-term efficacy up to month 72 and safety through month 96 in patients with RA receiving tofacitinib as monotherapy (ie, without background csDMARDs) or combination therapy (ie, with background csDMARDs) throughout. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib were also assessed in patients who switched from monotherapy to combination therapy (mono→combo switchers) or from combination therapy to monotherapy (combo→mono switchers).

Methods

Study design and patients

This analysis included pooled data from patients enrolled in two multicentre, open-label LTE studies (ORAL Sequel (A3921024; NCT00413699) and A3921041 (NCT00661661)).25 26

ORAL Sequel is an ongoing, global, open-label LTE study that enrolled adults with a diagnosis of RA who completed qualifying phase 1, 2 or 3 index studies of tofacitinib or had required earlier discontinuation of treatment from a qualifying study for reasons other than treatment-related serious adverse events (SAEs). As of the January 2016 data cut-off, the study was not completed, and the study database was not locked (ie, some values may change for the final, locked study database).

A3921041 was an open-label LTE study that was conducted in 56 centres in Japan and enrolled Japanese patients (aged ≥20 years) with a diagnosis of RA who had completed prior phase 2 and phase 3 index studies of tofacitinib in Japan or had required earlier discontinuation from a qualifying study for reasons other than treatment-related SAEs.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported previously.26 Dose adjustments of tofacitinib (from 5 mg to 10 mg twice daily and the reverse) and addition of concomitant RA medications (including MTX, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, antimalarials, auranofin, injectable gold preparations, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or glucocorticoids) were permitted for those with inadequate efficacy or for safety reasons. In A3921041 concomitant usage of csDMARDs including MTX was permitted after week 12.

The initial assigned tofacitinib dose was dependent on the study phase, requirements of the index study and the country of origin.26 For the purposes of this analysis, patients were assigned to tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily dose groups based on average total daily dose (TDD; sum of doses received divided by number of days a dose was received) in the LTE study. The tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily groups were defined as TDD <15 mg/day and TDD ≥15 mg/day, respectively. Baseline values were those of the index studies for patients who enrolled in the LTE within 14 days of the index study; for all other patients, baseline was the start of the LTE. Open-label treatment was initiated with tofacitinib 5 mg or 10 mg twice daily, as monotherapy or with background csDMARDs.

In this post hoc analysis, patients who received tofacitinib monotherapy (ie, without background csDMARDs) throughout the LTE studies were assigned to the monotherapy group. Those who initiated and remained on tofacitinib with background csDMARDs for the duration of their participation in the LTE study, or who had one break of ≤28 days from csDMARDs, were assigned to the combination therapy group. Combo→mono switchers were defined as patients who permanently stopped csDMARD treatment for >28 days and continued tofacitinib monotherapy for the remaining study period. Patients were categorised as mono→combo therapy switchers if they initiated treatment with monotherapy and added a csDMARD for the remainder of the study period. These patients were permitted a break in the use of csDMARDs for ≤28 days. Patients who switched multiple times were not included.

Endpoints and analyses

Efficacy was evaluated through month 72 for patients initiating and remaining on tofacitinib monotherapy or combination therapy. Efficacy analyses included: ACR20/50/70 response rates and improvements from baseline in Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-4(ESR)), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI). The proportion of patients achieving remission, defined as DAS28-4(ESR) <2.6 or CDAI ≤2.8, and LDA, defined as DAS28-4(ESR) ≤3.2 or CDAI ≤10, were evaluated along with the proportion of patients achieving HAQ-DI <0.5 and improvements in HAQ-DI greater than the minimum clinically important difference (MCID; ≥0.22 units). For patients who switched treatment regimens, efficacy analyses included mean DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI scores. Additionally, the time to treatment switch for the mono→combo switchers and the combo→mono switchers was calculated.

Safety was evaluated over 96 months of observation and included the proportions of patients with treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) and incidence rates (IRs; number of patients with events per 100 patient-years) for discontinuations due to AEs, SAEs and AEs of special interest, including serious infections, adjudicated opportunistic infections (OIs) excluding tuberculosis, herpes zoster, adjudicated tuberculosis, major adverse cardiovascular events, non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), malignancies (excluding NMSC) and lymphoma. The causality of each AE was assessed by the investigator as to whether there existed a reasonable possibility that the study drug caused or contributed to an AE. SAEs were defined as those that resulted in death or immediate risk of death, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or resulted in congenital anomalies/birth defects. Clinical laboratory parameters were evaluated through month 72 (due to low patient numbers thereafter).

Analyses were based on the full analysis set, which included all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment. IRs for serious infections were based on the number of patients with an event and total exposure time censored at the time of event, death or study discontinuation and were compared between treatment groups. Exact Poisson 95% CIs adjusted for exposure were calculated for IRs.

Descriptive statistics for efficacy endpoints were summarised at 3 months prior to treatment switch, at treatment switch and at 3, 6 and 12 months post-treatment switch to determine maintenance of response.

Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Independent Ethics Committees at each investigational centre. All patients provided written informed consent.

Results

Patients

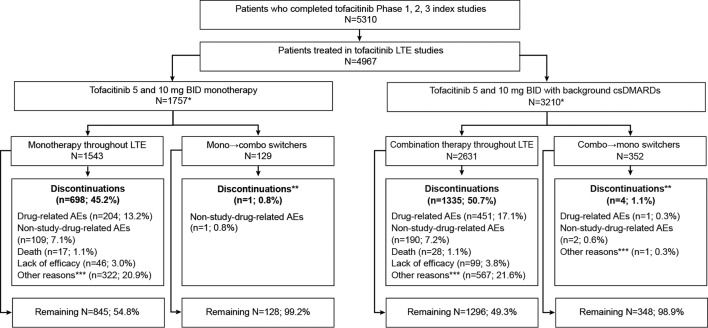

In total, 4967 patients were treated in the LTE studies (table 1). Of these, 35.4% (n=1757) initiated treatment with tofacitinib monotherapy and 64.6% (n=3210) initiated tofacitinib with background csDMARDs. The majority of patients (87.8%; 1543/1757) initiating monotherapy remained on monotherapy while participating in the LTE; the mean (median; range) treatment duration was 1303.6 days (1246; 3–3151) for tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 1155.0 days (1138; 1–2730) for tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. Of those initiating combination therapy, 82.0% (2631/3210) remained on combination therapy while participating in the LTE; mean (median; range) treatment duration with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg twice daily was 1281.7 days (1220; 1–3182) and 1101.9 days (1173; 1–2901), respectively. MTX was the most common background csDMARD and was used by 86.2% (2269/3210) of the patients initiating combination therapy. In patients who remained on combination therapy throughout the study, 90.0% (2367/2631) were receiving a single csDMARD at baseline, whereas 10.0% (264/2631) were receiving multiple csDMARDs at baseline. In total, 45.2% of patients receiving tofacitinib monotherapy and 50.7% of patients receiving combination therapy discontinued the LTE before completion; of these, 13.2% and 17.1%, respectively, discontinued from the study due to treatment-related AEs; 3.0% and 3.8%, respectively, discontinued due to insufficient clinical response (figure 1). Other reasons for discontinuation included non-treatment-related AEs (tofacitinib monotherapy: 7.1%; combination therapy: 7.2%), patients were no longer willing to participate in the study (monotherapy: 9.5%; combination therapy: 10.1%), patients were lost to follow-up (monotherapy: 2.6%; combination therapy: 2.4%), protocol violations (monotherapy: 2.4%; combination therapy: 2.7%), death (monotherapy: 1.1%; combination therapy: 1.1%), withdrawal due to pregnancy (monotherapy: 0.7%; combination therapy: 0.2%), termination of study by sponsor (monotherapy: 0.1%; combination therapy: 0.0%), patients who did not meet entrance criteria (monotherapy: 0.0%; combination therapy: 0.2%) and other reasons (monotherapy: 5.6%; combination therapy: 6.0%). Among patients who remained on monotherapy or combination therapy throughout the study, the median time until LTE discontinuation for all causes was 1838 days and 1595 days, respectively, and the median time to discontinuation due to treatment-emergent AEs was after the end of the study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients enrolled in the LTE studies

| Monotherapy*† n=1543 |

Combination therapy*‡ n=2631 |

Mono→combo switchers*§ n=129 |

Combo→mono switchers*¶ n=352 |

|||||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=496 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=1047 |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=775 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=1856 |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=46 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=83 |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=97 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=255 |

|

| Mean age (range), years | 54.6 (19–82) | 52.4 (19–85) | 53.2 (18–82) | 53.3 (18–86) | 51.2 (20–75) | 51.1 (20–71) | 55.5 (28–77) | 54.7 (20–82) |

| Female, n (%) | 422 (85.0) | 841 (80.3) | 633 (81.7) | 1514 (81.6) | 30 (65.2) | 66 (79.5) | 80 (82.5) | 207 (81.2) |

| White, n (%) | 228 (46.0) | 779 (74.4) | 374 (48.3) | 1273 (68.6) | 20 (43.5) | 52 (62.7) | 66 (68.0) | 197 (77.3) |

| Mean weight (SD), kg | 64.7 (16.6) | 73.7 (19.4) | 67.1 (17.5) | 73.0 (19.4) | 68.0 (17.8) | 71.5 (17.4) | 72.4 (20.0) | 76.9 (21.6) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 25.2 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.4) | 25.8 (6.1) | 27.5 (6.4) | 26.0 (5.7) | 26.8 (6.5) | 27.2 (6.0) | 28.4 (7.1) |

| Mean duration of RA (range), years | 7.7 (0.0–38.0) | 6.3 (0.0–55.0) | 8.6 (0.2–50.1) | 8.3 (0.1–49.4) | 6.2 (0.2–21.0) | 5.4 (0.1–33.0) | 9.1 (0.2–39.0) | 9.0 (0.1–41.0) |

| DAS28-4(ESR), mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.1 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.5 (1.0) | 6.2 (0.9) | 6.3 (1.1) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| Discontinuations during the LTE,** n (%) | 242 (48.8) | 456 (43.6) | 397 (51.2) | 938 (50.5) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) |

| Concomitant GC use at baseline, n (%) | 278 (56.0) | 436 (41.6) | 388 (50.1) | 975 (52.5) | 23 (50.0) | 46 (55.4) | 50 (51.5) | 129 (50.6) |

| Mean GC dose at baseline (SD), mg/day | 6.3 (6.1) | 6.5 (3.9) | 6.5 (3.6) | 6.4 (4.1) | 6.2 (3.1) | 6.1 (2.7) | 5.7 (3.9) | 5.8 (2.6) |

*Data as of January 2016, ongoing at time of analysis, database not locked.

†Patients received monotherapy throughout the LTE studies without concomitant csDMARDs.

‡Patients initiated and remained on background csDMARDs for the duration of their participation in the LTE study or had one break of ≤28 days from csDMARDs.

§Patients permanently stopped csDMARD treatment for >28 days and continued tofacitinib monotherapy for the remaining study period.

¶Patients initiated treatment with monotherapy and had a csDMARD added until the last dose of tofacitinib.

**For patients switching treatment regimens, discontinuations from study within 30 days of treatment switch are reported.

BMI, body mass index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DAS28-4(ESR), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GC, glucocorticoid; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LTE, long-term extension; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. *Patients who switched multiple times were not included in this analysis; **for patients switching treatment regimens, discontinuations from study within 30 days of treatment switch are reported; ***‘other reasons’ included patients lost to follow-up, patients no longer willing to participate, withdrawals due to pregnancy, protocol violations and study termination by sponsor. AE, adverse event; BID, twice daily; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; LTE, long-term extension.

Of the 1543 patients who remained on tofacitinib monotherapy, 23.4% (134/573) of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily increased their dose to 10 mg twice daily and remained on 10 mg twice daily; 7.5% (43/573) increased their dose to 10 mg twice daily before subsequently reverting back to 5 mg twice daily. Of the patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily as monotherapy, 14.0% (136/970) decreased their dose to 5 mg twice daily and remained on 5 mg twice daily; 3.6% (35/970) switched from 10 mg twice daily to 5 mg twice daily and back. In general, a slightly lower percentage of patients remaining on combination therapy switched doses, with 20.0% (170/852) and 3.6% (31/852) of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily switching dose once and twice, respectively, and 11.3% (201/1779) and 3.9% (69/1779) of patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily switching dose once and twice, respectively.

Only 2.6% of patients (n=129) were mono→combo switchers; the majority of these patients (69.0%) added MTX. In total, 7.1% (n=352) of patients were combo→mono switchers (figure 1). The median time to treatment switch was 15.0 months for both mono→combo and combo→mono switchers.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were generally similar for all treatment groups, although the mean duration of RA was greater for combo→mono switchers versus mono→combo switchers (table 1).

Of those remaining on monotherapy, fewer patients received glucocorticoids at month 72 versus baseline (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, 42.3% vs 56.0%; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily, 31.6% vs 41.6%, respectively); the mean daily dose of glucocorticoids for the combined tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily doses was similar at baseline (6.42 mg/day) and at month 72 (6.43 mg/day). Of those remaining on combination therapy with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily, fewer patients received glucocorticoids at month 72 versus baseline (44.9% vs 50.1%, respectively); however, more patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs received glucocorticoids at month 72 versus baseline (58.6% vs 52.5%, respectively). For those receiving background csDMARDs, the mean daily dose of glucocorticoids for the tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily doses decreased from 6.45 mg/day at baseline to 5.99 mg/day at month 72.

Efficacy

ACR20/50/70 response rates were sustained up to month 72 for patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily as monotherapy and those with background csDMARDs (online supplementary figure S1). At month 1, ACR20/50/70 response rates were 76.8%, 53.1% and 32.1%, respectively, with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily monotherapy and 75.1%, 52.4% and 34.1%, respectively, with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily monotherapy. Corresponding observed rates at month 72 were 84.9%, 68.7% and 42.4% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 84.6%, 56.4% and 35.9% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. Similarly, for the combination therapy group, ACR20/50/70 response rates at month 1 (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily: 71.1%, 47.5% and 26.1%, respectively; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily: 71.4%, 44.8% and 24.6%, respectively) were maintained through month 72 (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily: 82.8%, 60.3% and 37.1%, respectively; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily: 100.0%, 52.6% and 36.8%, respectively).

rmdopen-2017-000491supp001.jpg (727.4KB, jpg)

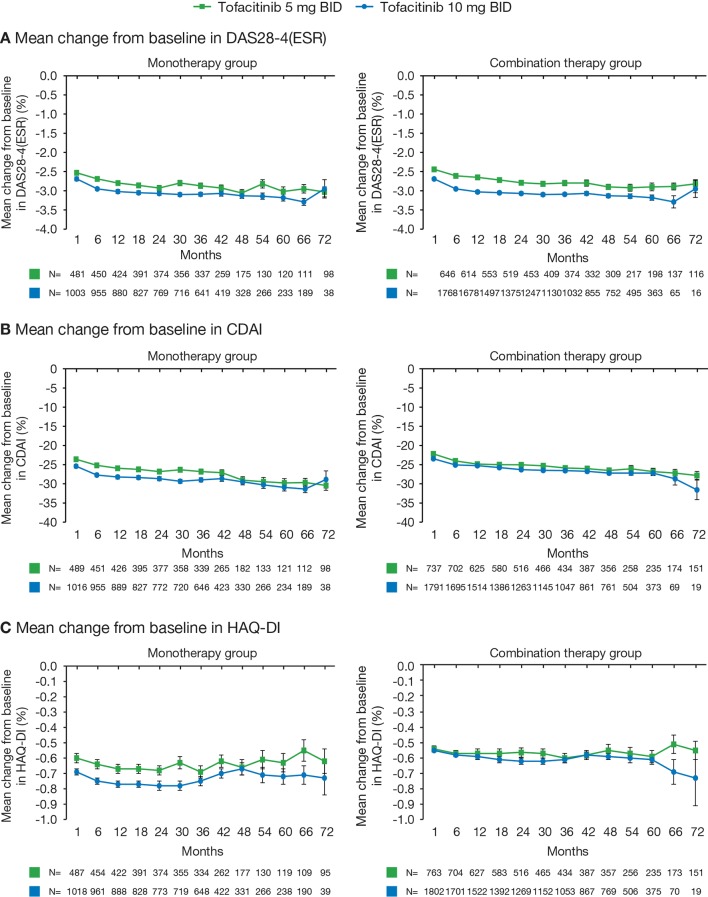

At month 1 in the monotherapy group, the mean changes from baseline in DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI were −2.53, –23.59 and −0.60, respectively, with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and −2.69, –25.41 and −0.69, respectively, with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. At month 72, corresponding rates were −3.03, –30.41 and −0.62, respectively, with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and −2.95, –28.88 and −0.73, respectively, with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily (figure 2). Similarly, in the combination therapy group, the mean changes from baseline in DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI at month 1 (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily: −2.45, –22.19 and −0.54, respectively; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily: −2.44, –23.45 and −0.55, respectively) were maintained through month 72 (tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily: −2.82, –27.81 and −0.55, respectively; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily: −2.82, −31.57 and −0.73, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean change from baseline in (A) DAS28-4(ESR), (B) CDAI and (C) HAQ-DI. Error bars show SE; reductions in patient numbers over time reflect that some patients have not reached time point. BID, twice daily; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-4(ESR), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index.

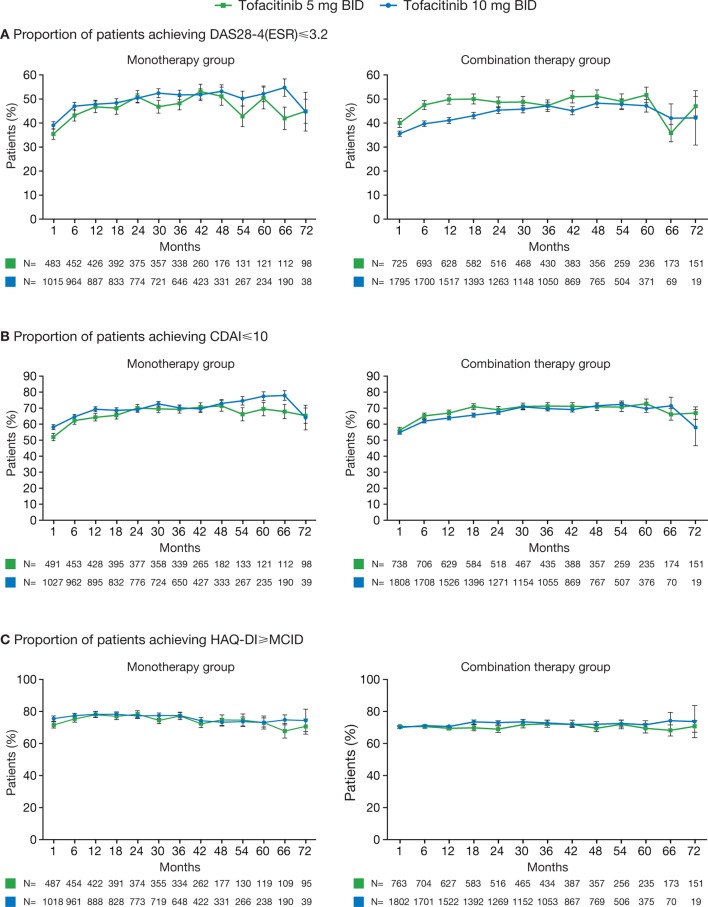

Rates of DAS28-defined and CDAI-defined remission and LDA were generally maintained through month 72 in all patients who had reached this time point (figure 3A,B, online supplementary figure S2 A,B). The proportion of patients achieving CDAI-defined remission decreased from baseline to month 72 in patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily with csDMARDs, although patient numbers at month 72 were low (n=19). The proportion of patients achieving HAQ-DI <0.5 was maintained for all patients, regardless of whether they received tofacitinib as monotherapy or with background csDMARDs (online supplementary figure S2C). For those receiving either monotherapy or combination therapy, rates of HAQ-DI ≥MCID were maintained throughout (figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) DAS28-4(ESR) ≤3.2, (B) CDAI ≤10 and (C) HAQ-DI ≥MCID. Error bars show SE; reductions in patient numbers over time reflect that some patients have not reached time point. BID, twice daily; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-4(ESR), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; MCID, minimum clinically important difference.

rmdopen-2017-000491supp002.jpg (759.6KB, jpg)

For combo→mono switchers, mean DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI scores at the time of treatment switch were maintained 12 months after the treatment switch. In contrast, for mono→combo switchers, mean DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI values 12 months following the treatment switch were numerically lower than at the time of treatment switch, although it should be noted that patient numbers were low (table 2).

Table 2.

Mean DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI scores in patients who switched treatment regimens during the LTE studies

| Mono→combo switchers | Combo→mono switchers | ||||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=46* |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=82† |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=97‡ |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=255§ |

||

| Mean DAS28-4(ESR) (SD) | 3 months before treatment switch | 3.95 (1.70) | 4.35 (1.56) | 3.47 (1.39) | 3.27 (1.23) |

| At treatment switch | 4.11 (1.76) | 4.73 (1.67) | 3.27 (1.21) | 3.17 (1.13) | |

| 3 months after treatment switch | 4.13 (1.71) | 4.41 (1.60) | 3.37 (1.31) | 3.16 (1.13) | |

| 6 months after treatment switch | 3.91 (1.63) | 4.35 (1.60) | 3.29 (1.32) | 3.06 (1.27) | |

| 12 months after treatment switch | 3.44 (1.51) | 4.24 (1.46) | 3.53 (1.29) | 3.20 (1.25) | |

| Mean CDAI (SD) | 3 months before treatment switch | 15.87 (18.83) | 16.15 (13.26) | 8.33 (9.85) | 7.86 (8.68) |

| At treatment switch | 19.08 (16.47) | 20.67 (14.67) | 7.44 (9.40) | 6.96 (7.29) | |

| 3 months after treatment switch | 16.65 (14.17) | 17.47 (14.12) | 7.91 (10.39) | 6.78 (6.86) | |

| 6 months after treatment switch | 14.26 (11.75) | 17.13 (15.46) | 7.74 (9.83) | 6.71 (8.24) | |

| 12 months after treatment switch | 9.97 (10.38) | 15.39 (12.32) | 7.88 (7.79) | 7.10 (7.73) | |

| Mean HAQ-DI (SD) | 3 months before treatment switch | 0.81 (0.85) | 1.03 (0.70) | 0.82 (0.68) | 0.68 (0.66) |

| At treatment switch | 0.94 (0.76) | 1.00 (0.71) | 0.69 (0.66) | 0.65 (0.64) | |

| 3 months after treatment switch | 0.89 (0.72) | 0.93 (0.74) | 0.75 (0.65) | 0.63 (0.64) | |

| 6 months after treatment switch | 0.77 (0.69) | 0.96 (0.73) | 0.62 (0.60) | 0.60 (0.64) | |

| 12 months after treatment switch | 0.73 (0.67) | 0.89 (0.77) | 0.68 (0.64) | 0.64 (0.65) | |

*3 months before treatment switch n=35 (34 for CDAI), at treatment switch n=46 (45 for CDAI, 44 for DAS28-4(ESR)), 3 months after treatment switch n=44 (42 for CDAI, 41 for DAS28-4(ESR)), 6 months after treatment switch n=38 (37 for CDAI, 36 for DAS28-4(ESR)), 12 months after treatment switch n=25.

†3 months before treatment switch n=67 (66 for DAS28-4(ESR) and HAQ-DI), at treatment switch n=82, 3 months after treatment switch n=78 (77 for DAS-284(ESR)), 6 months after treatment switch n=67, 12 months after treatment switch n=48 (47 for CDAI and HAQ-DI).

‡3 months before treatment switch n=84, at treatment switch n=97, 3 months after treatment switch n=90 (89 for DAS28-4(ESR) and HAQ-DI), 6 months after treatment switch n=87, 12 months after treatment switch n=74 (73 for DAS28-4(ESR) and CDAI).

§3 months before treatment switch n=210 (209 for HAQ-DI), at treatment switch n=255, 3 months after treatment switch n=242 (241 for HAQ-DI and 238 for DAS28-4(ESR)), 6 months after treatment switch n=218, 12 months after treatment switch n=190 (189 for DAS28-4(ESR)).

CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-4(ESR), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; LTE, long-term extension.

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs were experienced by 93.8% and 87.8% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, as monotherapy, and 88.6% and 88.8% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, with background csDMARDs (table 3). The most common AEs across all treatment groups were bronchitis, nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. Discontinuations due to treatment-emergent AEs for patients receiving tofacitinib as monotherapy were 25.4% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 19.2% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. For those receiving tofacitinib with background csDMARDs, discontinuations due to AEs were experienced by 27.4% of patients with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 24.4% of patients with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. Discontinuations due to AEs within 30 days of the treatment switch for the mono→combo switchers were 2.2% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 0.0% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. For combo→mono switchers, discontinuations due to AEs were experienced by 1.0% with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and 0.8% with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. The most common AEs for the mono→combo switchers were nausea and hypertension, whereas for the combo→mono switchers, the most common AEs were urinary tract infection, bronchitis and hypertension.

Table 3.

IRs (number of patients with events/100 patient-years) for AEs of special interest

| Monotherapy*† n=1543 |

Combination therapy*‡ n=2631 |

|||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=496 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=1047 |

Tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily n=775 |

Tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily n=1856 |

|

| Exposure, patient-years | 1788.61 | 3344.8 | 2740.54 | 5656.52 |

| Patients with AEs, n (%) | 465 (93.8) | 919 (87.8) | 687 (88.6) | 1649 (88.8) |

| Discontinuations due to AEs, n (%) | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 126 (25.4) | 201 (19.2) | 212 (27.4) | 452 (24.4) |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 7.13 (5.94 to 8.49) | 6.06 (5.25 to 6.96) | 7.82 (6.80 to 8.95) | 8.06 (7.33 to 8.84) |

| SAEs | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 150 | 257 | 207 | 544 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 9.42 (7.98 to 11.06) | 8.41 (7.41 to 9.50) | 8.36 (7.26 to 9.58) | 10.75 (9.86 to 11.69) |

| Serious infections | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 43 | 83 | 60 | 188 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 2.42 (1.75 to 3.26) | 2.49 (1.98 to 3.09) | 2.22 (1.70 to 2.86) | 3.35 (2.89 to 3.86) |

| Prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 28 | 40 | 35 | 126 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 2.77 (1.84 to 4.01) | 2.63 (1.88 to 3.58) | 2.59 (1.80 to 3.60) | 4.21 (3.51 to 5.02) |

| No prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 15 | 43 | 25 | 62 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 1.95 (1.09 to 3.22) | 2.37 (1.72 to 3.20) | 1.86 (1.20 to 2.74) | 2.36 (1.81 to 3.02) |

| Adjudicated opportunistic infections (excluding TB) | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 6 | 9 | 7 | 24 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.34 (0.12 to 0.73) | 0.27 (0.12 to 0.51) | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.53) | 0.43 (0.27 to 0.63) |

| Herpes zoster | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 67 | 81 | 71 | 220 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 4.12 (3.19 to 5.23) | 2.55 (2.02 to 3.17) | 2.79 (2.18 to 3.51) | 4.19 (3.65 to 4.78) |

| Prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 44 | 42 | 36 | 120 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 4.89 (3.55 to 6.56) | 2.91 (2.10 to 3.94) | 2.81 (1.97 to 3.89) | 4.32 (3.58 to 5.17) |

| No prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 23 | 39 | 35 | 100 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 3.16 (2.01 to 4.75) | 2.24 (1.60 to 3.07) | 2.76 (1.92 to 3.84) | 4.04 (3.29 to 4.91) |

| Adjudicated TB | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 3 | 5 | 4 | 12 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.17 (0.04 to 0.49) | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.35) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.37) | 0.21 (0.11 to 0.37) |

| MACE§ | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 9 | 7 | 13 | 28 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.53 (0.24 to 1.00) | 0.21 (0.08 to 0.43) | 0.54 (0.29 to 0.92) | 0.50 (0.33 to 0.72) |

| NMSC | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 9 | 12 | 10 | 46 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.51 (0.23 to 0.97) | 0.36 (0.19 to 0.63) | 0.37 (0.18 to 0.67) | 0.83 (0.60 to 1.10) |

| Malignancies (excluding NMSC) | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 18 | 26 | 35 | 45 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 1.01 (0.60 to 1.59) | 0.78 (0.51 to 1.14) | 1.28 (0.89 to 1.78) | 0.80 (0.58 to 1.07) |

| Prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 11 | 11 | 19 | 23 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 1.09 (0.54 to 1.95) | 0.72 (0.36 to 1.29) | 1.39 (0.83 to 2.16) | 0.76 (0.48 to 1.15) |

| No prior GC use at baseline | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 7 | 15 | 16 | 22 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.90 (0.36 to 1.86) | 0.83 (0.46 to 1.36) | 1.17 (0.67 to 1.90) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.26) |

| Lymphoma | ||||

| Unique patients with events, n | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| IR/100 patient-years (95% CI) | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.31) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.17) | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.32) | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.23) |

*Data as of January 2016, ongoing at time of analysis, database not locked.

†Patients received monotherapy throughout the LTE studies without concomitant csDMARDs.

‡Patients initiated and remained on background csDMARDs for the duration of their participation in the LTE study or had one break of ≤28 days from csDMARDs.

§Data for MACE are based on adjudicated events: tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily monotherapy n=480; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily monotherapy n=1087; tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs n=707; tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs, n=1856.

AE, adverse event; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GC, glucocorticoid; IR, incidence rate; LTE, long-term extension; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; SAE, serious adverse event; TB, tuberculosis.

IRs for AEs of special interest were generally consistent across all treatment groups, with some exceptions. IRs for malignancy (excluding NMSC) and lymphoma were numerically greater when tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg twice daily) was administered with background csDMARDs rather than as monotherapy (table 3). Across the combination therapy and monotherapy groups, respectively, the most common malignancy types were lung cancer (n=17, n=8), breast cancer (n=14, n=5) and lymphoma (n=9, n=2). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was the most common type of lymphoma (B cell neoplasm: n=4, n=1; T cell and natural killer cell neoplasms: n=1, n=0; unspecified type: n=3, n=0), with Hodgkin lymphoma also reported (n=1, n=1). IRs for NMSC were numerically greater with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily combination therapy versus monotherapy or combination therapy with 5 mg twice daily. IRs for adjudicated OIs excluding TB were numerically greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily monotherapy and tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily combination therapy compared with other treatment groups. Across the combination therapy and monotherapy groups, respectively, the most common OIs were multidermatomal/disseminated herpes zoster (n=19, n=6), cytomegalovirus disease (n=5, n=0), pneumocystosis (n=4, n=1) and oesophageal candidiasis (n=2, n=3). IRs for herpes zoster were greater with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily monotherapy and tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily combination therapy versus the other treatment groups. IRs for SAEs and serious infections were also numerically greater for patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs versus the other treatment groups. Interstitial lung disease was reported in 18 and 9 patients who remained on combination therapy and monotherapy, respectively. The proportion of fatalities was 1.1% for both those remaining on combination therapy (28/2631) and monotherapy (17/1543; figure 1); the most common causes of death were pneumonia (n=5, n=3) and lung cancer (n=4, n=1).

Confirmed increases in alanine aminotransferase >3 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) were observed in 1.6% and 1.4% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily monotherapy, respectively, and in 2.1% and 1.9% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, in combination with csDMARDs. Elevations in aspartate aminotransferase >3 × ULN were observed in 0.8% and 0.7% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily monotherapy, respectively, and 1.0% and 1.1% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively, as combination therapy. Two patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily combination therapy developed drug-induced liver injury; one patient subsequently discontinued treatment. No cases of drug-induced liver injury were reported in patients receiving tofacitinib monotherapy.

The mean changes from baseline in neutrophil counts, as well as serum creatinine, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol and triglyceride levels generally remained stable through month 72 across all treatment groups (online supplementary figure S3 and S4).

Discussion

Due to the chronic nature of RA, effective therapeutic options should demonstrate long-term efficacy and tolerability in addition to efficacy and safety in short-term RCTs. In this post hoc analysis of LTE studies, the efficacy of tofacitinib was maintained through month 48 and appeared to continue to month 72, although lower patient numbers towards the end of the study necessitate caution when interpreting these results; in total, 111 patients receiving monotherapy and 157 patients receiving combination therapy continued treatment beyond month 72, and safety was consistent over 96 months when tofacitinib was administered as monotherapy and with background csDMARDs.

In this analysis, clinically meaningful reductions in the signs and symptoms of RA, as measured by ACR20/50/70 response rates, change from baseline in DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI, and DAS-defined and CDAI-defined remission and LDA were maintained up to month 72 in those patients completing this time point, thus demonstrating that the efficacy previously reported in short-term phase 2 and phase 3 studies of tofacitinib can be sustained in these patients.14–16 18–23

Of importance, for each outcome analysed, efficacy was maintained regardless of whether tofacitinib was administered as monotherapy or with background csDMARDs. Mean DAS28-4(ESR), CDAI and HAQ-DI decreased slightly by month 12 if patients switched from monotherapy to combination therapy and were maintained if patients switched from combination therapy to monotherapy. These results contrast with the data obtained in RCTs of all TNFi, which report greater efficacy with combination therapy versus monotherapy. For example, phase 3 and LTE studies of TNFi monotherapy have shown that adalimumab, etanercept and abatacept were associated with improved efficacy when administered in combination with MTX compared with monotherapy,5 7 11 27 28 and a network meta-analysis reported similar trends in terms of ACR responses for all TNFi (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab).29 In studies of non-TNFi agents, tocilizumab also demonstrated better efficacy with comparable safety when administered as combination therapy rather than as monotherapy in early RA,6 although no clinical superiority of tocilizumab plus MTX over tocilizumab monotherapy was identified in established RA.30 Within our analysis, the majority of patients (1543/1757; 87.8%) who were treated with tofacitinib monotherapy in the index studies did not require addition of a csDMARD to sustain their response and remained on tofacitinib monotherapy for the duration of their participation in the LTE studies (figure 1). This analysis investigated the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy over a 6-year period. As such, these data provide clinicians with important insights into the potential benefits of long-term treatment with tofacitinib monotherapy. However, it is important to note that although different trends can be observed with tofacitinib and TNFi monotherapy versus combination therapy, a direct comparison of the efficacy of tofacitinib and TNFi therapy was not planned and, as such, no conclusions can be drawn as to the superiority of one treatment over another.

The safety profile of tofacitinib was generally manageable, and similar safety signals as noted in RCTs were seen.15 16 18–23 31 The proportions of patients who discontinued treatment were generally comparable with those observed for other RA treatments in LTE studies; however, direct comparisons cannot be made due to the different lengths of each study.32–34 Although IRs for safety events of special interest were generally consistent across treatment groups, IRs for SAEs and serious infections were numerically greater with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs compared with tofacitinib monotherapy (5 mg or 10 mg) or tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs. This is consistent with findings from phase 3 studies that also reported higher IRs for AEs, SAEs and serious infections in patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with background csDMARDs compared with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily monotherapy.35 Furthermore, patients receiving tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg twice daily) with background csDMARDs had numerically higher IRs for malignancy (excluding NMSC) and lymphoma compared with those receiving monotherapy. This is supported by a previous analysis of malignancies in phase 3 studies, in which IRs were numerically lower in the tofacitinib monotherapy group (both doses) than in the combination therapy group.36

The mean change from baseline in serum lipids and creatinine levels and neutrophil and lymphocyte counts were maintained throughout the LTE study for patients receiving tofacitinib as monotherapy and with background csDMARDs. Previous analyses have demonstrated that tofacitinib increased serum triglycerides, LDL and HDL levels to a similar extent when administered as monotherapy or in combination therapy with csDMARDs; however, it was noted that most increases occurred within the first 3 months of treatment and stabilised thereafter.37

The limitations of this analysis include the open-label study design and lack of a placebo comparator group. In addition, only patients who completed or withdrew from a qualifying index study due to reasons other than treatment-related SAEs were eligible for enrolment in the LTE studies, resulting in selection bias due to the inclusion of patients with improved efficacy without significant AEs. Furthermore, the nature of these analyses meant that efficacy outcomes were reported using observed case data only with no formal statistics to compare treatment groups. As dose adjustments were permitted in the LTE study and patient disease states may have changed over the course of the study, limited comparisons could be made between tofacitinib doses. Comparisons of data between monotherapy and combination therapy groups should also be treated with caution because patients were not randomised to one treatment group versus the other, and each index study defined the regimen for all patients within that study. Given the different study designs, comparisons between the LTE data presented here and the data reported in RCTs of TNFi should also be treated with caution. Last, although the data reported here included patients with up to 96 months of exposure to tofacitinib in the LTE studies, the numbers of patients after month 72 are low and consequently efficacy data and laboratory data are not reported beyond this time point. Nevertheless, open-label studies, such as those reported here, can play a role in characterising the safety and maintenance of efficacy of drugs with novel mechanisms of actions such as tofacitinib.

In conclusion, tofacitinib 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily demonstrated sustained efficacy through month 72 and consistent safety with up to 96 months of observation. Efficacy and safety were sustained regardless of whether patients received tofacitinib as monotherapy or with background csDMARDs or whether they switched to either monotherapy or combination therapy during the LTE studies.

rmdopen-2017-000491supp003.jpg (730KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp004.jpg (708.5KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp005.docx (20.9KB, docx)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators and study teams who were involved in the LTE studies. Statistical support was provided by Amy Stein of Quintiles. Editorial support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Stephanie Johnson, PhD, at Complete Medical Communications, Macclesfield, UK, and Christina Viegelmann, PhD, at Complete Medical Communications, Glasgow, UK, and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York City, New York, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the interpretation of study results, critical revision of the article and final approval of the version to be published. In addition, RF, JW and RFvV were involved in the acquisition of data. LT, AM, KK and LW were also involved in the conception or design of the study and the analysis of the data.

Funding: This work was supported by Pfizer Inc.

Competing interests: RF has received grant/research support from Pfizer Inc and is a consultant for Pfizer Inc. JW is a consultant for Pfizer Inc and is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Pfizer Inc. RFvV has received grant/research support from Pfizer Inc and is a consultant for Pfizer Inc. LW, AM, KK and LT are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc.

Ethics approval: The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Independent Ethics Committees at each investigational centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2001;358:903–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06075-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2205–19. 10.1056/NEJMra1004965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges-Jr SL, et al. . American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. . The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. . Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1081–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. . Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:19–26. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland L, et al. . Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor and monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2272–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emery P, Fleischmann R, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, et al. . The efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate treatment: results of a phase IIB randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1390–400. 10.1002/art.21778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keystone E, Genovese MC, Klareskog L, et al. . Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy: 52-week results of the GO-FORWARD study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1129–35. 10.1136/ard.2009.116319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. . Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. . Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. . Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:3–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. . Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61424-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kremer J, Li ZG, Hall S, et al. . Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:253–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kremer JM, Cohen S, Wilkinson BE, et al. . A phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) versus placebo in combination with background methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:970–81. 10.1002/art.33419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka Y, Suzuki M, Nakamura H, et al. . Phase II study of tofacitinib (CP-690,550) combined with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:1150–8. 10.1002/acr.20494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, et al. . Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve-month data from a twenty-four-month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:559–70. 10.1002/art.37816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. . Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:508–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1112072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. . Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:495–507. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischmann R, Cutolo M, Genovese MC, et al. . Phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:617–29. 10.1002/art.33383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kremer JM, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, et al. . The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP-690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1895–905. 10.1002/art.24567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, et al. . Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2377–86. 10.1056/NEJMoa1310476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamann P, Holland R, Hyrich K, et al. . Factors associated with sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis in patients treated with anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor (anti-TNF). Arthritis Care Res 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, et al. . Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open-label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol 2014;41:837–52. 10.3899/jrheum.130683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamanaka H, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, et al. . Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, as monotherapy or with background methotrexate, in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:34 10.1186/s13075-016-0932-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Heijde D, Breedveld FC, Kavanaugh A, et al. . Disease activity, physical function, and radiographic progression after longterm therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate: 5-year results of PREMIER. J Rheumatol 2010;37:2237–46. 10.3899/jrheum.100208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewé R, et al. . Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3928–39. 10.1002/art.23141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckley F, Finckh A, Huizinga TW, et al. . Comparative efficacy of novel DMARDs as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional DMARDs: a network meta-analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:409–23. 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.5.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. . Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2-year randomised controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:43–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burmester G, Charles-Schoemann C, Isaacs J, et al. . Tofacitinib, an oral Janus Kinase inhibitor: safety comparison in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to nonbiologic or biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:245 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.76623060009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischmann R, van Vollenhoven RF, Vencovský J, et al. . Long-term maintenance of certolizumab pegol safety and efficacy, in combination with methotrexate and as monotherapy, in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Ther 2017;4:57–69. 10.1007/s40744-017-0060-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klareskog L, Gaubitz M, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. . Assessment of long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in a 5-year extension study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:238–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furst DE, Kavanaugh A, Florentinus S, et al. . Final 10-year effectiveness and safety results from study DE020: adalimumab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to standard therapy. Rheumatology 2015;54:2188–97. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kivitz A, Haraoui B, Kaine J, et al. . A safety analysis of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily administered as monotherapy or in combination with background conventional synthetic DMARDs in a Phase 3 rheumatoid arthritis population. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Lee EB, Kaplan IV, et al. . Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor: analysis of malignancies across the rheumatoid arthritis clinical development programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:831–41. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charles-Schoeman C, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Kaplan I, et al. . Effects of tofacitinib and other DMARDs on lipid profiles in rheumatoid arthritis: implications for the rheumatologist. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:71–80. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2017-000491supp001.jpg (727.4KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp002.jpg (759.6KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp003.jpg (730KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp004.jpg (708.5KB, jpg)

rmdopen-2017-000491supp005.docx (20.9KB, docx)