Abstract

Background:

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) is the most abundant steroid in human circulation, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is considered the major regulator of its synthesis. Pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) and 5-androstenediol-3-sulfate (AdiolS) have recently emerged as biomarkers of adrenal disorders.

Objective:

To define the relative human adrenal production of Δ5-steroid sulfates under basal and cosyntropin-stimulated conditions.

Methods:

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was used to quantify three unconjugated and four sulfated Δ5-steroids in (1) paired adrenal vein (AV) and mixed venous serum samples (21 patients) and (2) cultured human adrenal cells both before and after cosyntropin stimulation, (3) microdissected zona fasciculata (ZF) and zona reticularis (ZR) from five human adrenal glands, and (4) a reconstituted in vitro human 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase/(P450 17A1) system.

Results:

Of the steroid sulfates, PregS had the greatest increase after cosyntropin stimulation in the AV (32-fold), whereas DHEAS responded modestly (1.8-fold). PregS attained concentrations comparable to those of DHEAS in the AV after cosyntropin stimulation (AV DHEAS/PregS, 24 and 1.3 before and after cosyntropin, respectively). In cultured adrenal cells, PregS demonstrated the sharpest response to cosyntropin, whereas DHEAS responded only modestly (21-fold vs 1.8-fold higher compared with unstimulated cells at 3 hours, respectively). Steroid analyses in isolated ZF and ZR showed similar amounts of PregS and 17α-hydroxypregnenolone in both zones, whereas DHEAS and AdiolS were higher in ZR (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Our studies demonstrated that unlike DHEAS, PregS displayed a prominent acute response to cosyntropin. PregS could be used to interrogate the acute adrenal response to ACTH stimulation and as a biomarker in various adrenal disorders.

Our studies demonstrate that in contrast with DHEAS, pregnenolone sulfate displays a prominent acute response to ACTH in vivo (adrenal vein samples) and in vitro (cultured human adrenal cells).

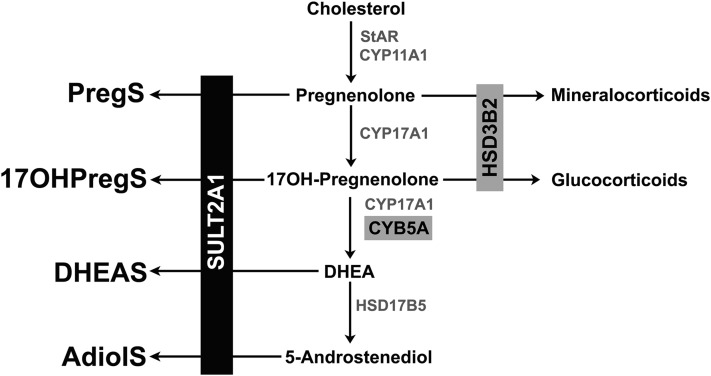

The process of sulfation enhances solubility and protein binding for steroids in the circulation, where they serve as inactive reservoirs for more hydrophobic, unconjugated precursors to active steroids (1, 2). In addition, considerable evidence demonstrates that steroid sulfates directly activate cell surface receptors and thus influence neuromodulation and possibly reproduction (3–5). In the adrenal gland, sulfotransferase type 2A (SULT2A1) sulfates the 3β-hydroxyl group of the Δ5-steroids pregnenolone (Preg), 17α-hydroxypregnenolone (17OHPreg), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androsta-5-ene-3β,17β-diol to form Preg sulfate (PregS), 17OHPreg sulfate (17OHPregS), DHEA sulfate (DHEAS), and 5-androstenediol-3-sulfate (AdiolS), respectively (Fig. 1). SULT2A1 deficiency has not been described to date, but mutations in the enzyme PAPS synthase 2, which provides the mandatory sulfate donor of all sulfotransferases, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate, cause elevated DHEA and downstream androgen levels (6, 7).

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of steroid sulfates. SULT2A1 is required for the synthesis of the Δ5-steroid sulfates, PregS, 17OHPregS, DHEAS, and AdiolS. CYB5A, cytochrome b5 type A; CYP11A1, cytochrome P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage; CYP17A1, 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase; HSD17B5, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5; HSD3B2, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein.

Steroid sulfates can be hydrolyzed to their respective unconjugated Δ5-steroids by the enzyme steroid sulfatase. Nevertheless, DHEAS concentrations in human serum are 100-fold higher than those of DHEA (8). Circulating DHEAS has a much lower rate of clearance than DHEA and, as a result of its extended half-life, demonstrates little diurnal rhythm (9). Chronically, however, DHEAS is thought to be regulated by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and is viewed as a reflection of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis integrity (10). DHEAS has been proposed as an auxiliary tool for the diagnosis of secondary adrenal insufficiency (11, 12) and autonomous adrenal hypercortisolism (13, 14), although studies have disagreed over both applications (15, 16). Remarkably, DHEAS is paradoxically low in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD), including those in poor control despite chronic ACTH stimulation and elevation of other 19-carbon steroids (17, 18). In contrast, we recently found that patients with classic 21OHD had higher PregS levels than sex- and age-matched controls (18). In a subsequent study of children and adults with classic 21OHD, we showed that PregS correlated with ACTH, whereas DHEAS did not (19).

Beyond the extensive studies of DHEAS, the dynamic regulation of other adrenal-derived steroid sulfates is poorly understood. Given the emerging data supporting promising clinical applications of PregS, 17OHPregS, and AdiolS as biomarkers of adrenal disease and maturation (18–20), we compared the synthesis of these three adrenal-derived steroid sulfates with DHEAS in humans under basal and cosyntropin-stimulated conditions both in vivo and in vitro.

Participants and Methods

Human sera

Adrenal vein (AV) sampling was performed as clinically indicated in patients undergoing evaluation for primary aldosteronism at the University of Michigan. Leftover sera from 21 patients (14 men and seven women) aged 33 to 78 years with unilateral primary aldosteronism were used for these studies (Supplemental Table 1 (438.6KB, docx) ). None of the patients were taking glucocorticoids at the time of AV sampling. Samples were obtained from the inferior vena cava (IVC; mixed venous blood) and AV before and 10 to 30 minutes after cosyntropin administration (injected as a 0.125-mg bolus followed by a 0.125-mg/h continuous infusion). Successful catheterization was confirmed by a minimum AV/IVC cortisol gradient of 2 at baseline and 5 after cosyntropin administration. To minimize the influence on dysregulated steroidogenesis, only AV samples from the nondominant side of patients with unilateral primary aldosteronism were used. All samples were collected under institutional review board–approved protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Adrenal cell culture and steroid production experiments

Adrenal glands were collected from deceased kidney donors (five men, aged 20 to 49 years) through the Gift of Life Michigan program and after institutional review board approval. Adrenal cells were isolated as previously described (21). Briefly, adrenal tissue was minced and dissociated into a single-cell suspension by repeated exposure of the tissue fragments to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 medium containing 1 mg/mL of collagenase/dispase and 0.25 mg/mL of deoxyribonuclease 1 (Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). Three 1-hour cycles of digestion at 37°C and mechanical dispersion were performed. Cells were collected between each digestion and combined before storage at −150°C. The cells were plated at a density of 15,000 cells per well in 48-well dishes and cultivated in growth medium to achieve 70% confluence. Subsequently, the cells were placed in low-serum medium 18 hours before treatment with 10 nM of cosyntropin for up to 48 hours. At the end of each treatment, the medium was collected from each well and stored at −20°C until steroid quantitation, whereas the cells were frozen at −80°C for protein assay. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Adrenal tissue experiments

Adrenal glands (n = 5) were trimmed free of fat and placed in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Zona fasciculata (ZF) and zona reticularis (ZR) tissue was isolated by microdissection of the adrenal gland as previously described (22). In short, under the dissecting microscope (SZ40; Olympus, Center Valley, PA), glands were placed in culture medium without phenol red (DMEM/F12 medium; Life Technologies) and sliced. The boundary between the ZF and ZR was visually identified, and fragments of zonal tissue were excised by inspection of color (bright yellow for ZF and reddish-brown for ZR). The fragments from the same tissue type were pooled together and frozen at −80°C until further use. A mixture of 10 mM of Tris·HCl (pH, 7.4) and 1 mM of EDTA was added to the ZF and ZR tissue (65 µL/1 mg tissue) in a lysing matrix D tube (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), and the tissue was ground in a FastPrep bead-milling homogenizer. The mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C for later steroid quantification by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Human 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase/P450 17A1 activity assay

The expression plasmids were generous gifts from the following investigators: modified human P450 17A1-G3H6 in pCW and N-27-human cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR)-G3H6 in pET22 from Professor Walter L. Miller (University of California, San Francisco) and human cytochrome b5 type A (CYB5A) in pLW01-b5H4 from Professor Lucy Waskell (University of Michigan). PregS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, and 17OHPregS was synthesized as previously described (18).

Modified human P450 17A1 was expressed with GroEL/ES chaperones (pGro7 plasmid) in Escherichia coli JM109 cells as described (23). Modified human POR was expressed in E. coli C41(DE3) cells (OverExpress; Lucigen, Middleton, WI) and was purified according to a previously published procedure (24). Purified P450 17A1 preparations showed a specific content of 8 to 12 nmol P450/mg protein with 3% to 10% P420. The protocol for expression and reconstitution of recombinant human CYB5A was based on the procedure of Mulrooney and Waskell (25).

P450 17A1 (10 to 100 pmol; final concentration, 0.05 to 0.5 μM) was reconstituted with 1 molar equivalent of POR with or without 1 molar equivalent of CYB5A and 100 molar equivalents phospholipid (1,2-didodecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; final concentration, 5 to 50 µM). The mixture was set at room temperature for 5 minutes and diluted to 0.2 mL with 50 mM of potassium phosphate buffer (pH, 7.4) or 50 mM of HEPES (pH, 7.4) containing 1 mM of MgCl2 and substrate at various concentrations. The resulting mixture was mixed gently and set at 37°C for 3 minutes. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) (1 mM) was added, and the incubation was continued at 37°C for 5 to 20 minutes. The reaction mixture was quenched by addition of 20 μL of 3 N HCl and stored at −20°C. Steroids were later quantified by LC-MS/MS. All reactions were run in triplicate.

Steroid quantitation by LC-MS/MS

Measurement of Δ5 unconjugated steroids and steroid sulfates from sera and media was performed by LC-MS/MS after liquid-liquid extraction, as previously described (18, 20, 26). Steroid calibration and internal standards were purchased from Cerilliant (Preg, 17OHPreg, and DHEA; Round Rock, TX), Sigma-Aldrich (DHEAS, DHEAS-d6, and DHEA-d5), and C/D/N Isotopes (PregS-d4; Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada) or were synthesized as previously described (PregS, 17OHPregS, and AdiolS) (18). The steroid sulfates were extracted from tissues as reported previously (27). Briefly, 75 µL of a mixture of internal standard deuterated steroids at known concentrations was added to a 75-µL aliquot of centrifuged lysate followed by 2 mL of methanol. The suspension was vortexed for 5 minutes followed by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 2500 rpm and 4°C and was then mixed with 2 mL of hexane. After vortexing, the mixture was again centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2500 rpm and 4°C, and the lower methanol layer was evaporated under nitrogen. The dried residue was mixed with 2 mL of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH, 5.0) for 30 seconds, and the mixture was loaded onto a SEP-PAK C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA), which was conditioned before loading with sequential washes of 5 mL each methanol, water, and 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH, 5.0). After the loaded cartridge was washed with 3 mL of water, steroid sulfates were eluted with 3 mL of methanol and collected in a clean glass vial. The eluate was dried under nitrogen gas at 37°C, and the residue was resuspended in 75 μL methanol of methanol/deionized water (1:1), transferred to a 0.25-mL vial insert, and stored at −20°C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

Protein extraction and protein assay

Cells were lysed in 100 µL of mammalian protein extraction reagent (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL), and the protein content was estimated by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay using the microbicinchoninic acid protocol (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Statistical analyses

Concentrations of steroids before and after cosyntropin treatment and of ZF and ZR steroid content were compared using a two-tailed paired t test with 95% confidence intervals. Comparison between different steroids was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical analysis for cell culture data was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by a Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons and t tests for single variables, as appropriate. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

AV and peripheral profiles of Δ5 unconjugated steroids and steroid sulfates

Before cosyntropin infusion, DHEAS was the dominant steroid in the AV and IVC, followed by AdiolS, PregS, and 17OHPregS (Table 1A). Baseline DHEAS concentrations were 24- and 36-fold higher than those of PregS in the AV and IVC, respectively (Table 1B). Of the steroid sulfates, PregS and 17OHPregS demonstrated much greater maximal responses to cosyntropin (32- and 29-fold, respectively) in the AV (P < 0.0001) than DHEAS and AdiolS, which increased only 1.8-fold from baseline (P = 0.02) or showed no increment, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 1 (438.6KB, docx) ; Table 1). After cosyntropin administration, PregS attained concentrations similar to those of DHEAS in the AV samples (AV DHEAS/PregS, 1.3, Table 1B). Relative to the IVC, postcosyntropin AV concentrations of PregS and 17OHPregS were 32- and 35-fold higher (P < 0.0001 for both), respectively, whereas DHEAS was only 2.2-fold higher in the AV as in the IVC after cosyntropin stimulation (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Effect of Cosyntropin on Steroid Concentrations and Ratios in the AV and IVC

| A. Steroid Concentrations in the AV and IVC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid | Precosyntropin | Postcosyntropin | Fold Change (Post/Pre) | |||||

| AV (nmol/L) | IVC (nmol/L) | AV/IVC (P Value) | AV (nmol/L) | IVC (nmol/L) | AV/IVC (P Value) | AV (P Value) | IVC (P Value) | |

| PregS | 100 [54–210] | 66 [26–84] | 1.9 (0.02) | 2996 [2563–4833] | 91 [66–161] | 32 (<0.0001) | 32 (<0.0001) | 1.7 (0.006) |

| 17OHPregS | 22 [11–41] | 6.0 [3.0–16] | 3.4 (0.0008) | 554 [422–840] | 16 [12–20] | 35 (<0.0001) | 29 (<0.0001) | 3.0 (0.002) |

| DHEAS | 2374 [1772–3561] | 2187 [1351–3409] | 1.2 (0.3) | 4730 [2788–6514] | 2185 [1271–2882] | 2.2 (0.001) | 1.8 (0.02) | 1.0 (0.8) |

| AdiolS | 330 [170–804] | 351 [185–773] | 1.0 (0.9) | 316 [179–753] | 322 [200–723] | 1.0 (>0.99) | 1.0 (>0.99) | 1.0 (0.9) |

| Preg | 2.8 [1.8–4.0] | 1.3 [0.8–2.6] | 2.1 (0.003) | 1502 [1280–1900] | 2.6 [2.1–4.3] | 551 (<0.0001) | 578 (<0.0001) | 2.0 (0.0009) |

| 17OHPreg | 10 [6.7–25] | 0.9 [0.2–3.2] | 32 (<0.0001) | 2863 [2280–3542] | 7.7 [4.3–13] | 370 (<0.0001) | 267 (<0.0001) | 7.1 (<0.0001) |

| DHEA | 36 [26–75] | 11 [3.5–20] | 5.0 (<0.0001) | 1725 [1304–3198] | 15 [5.3–30] | 134 (<0.0001) | 49 (<0.0001) | 1.3 (0.3) |

| B. Steroid Ratios in the AV and IVC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steroid Ratios | Precosyntropin | Postcosyntropin | Fold Change (Post/Pre) | |||||

| AV | IVC | AV/IVC (P Value) | AV | IVC | AV/IVC (P Value) | AV (P Value) | IVC (P Value) | |

| PregS/Preg | 28 [14–49] | 41 [27–54] | 0.9 (0.2) | 2.2 [1.8–2.6] | 37 [27–47] | 0.06 (<0.0001) | 0.07 (<0.0001) | 0.9 (0.6) |

| 17OHPregS/17OHPreg | 1.4 [0.8–2.3] | 4.9 [2.3–32] | 0.3 (0.0002) | 0.2 [0.1–0.3] | 2.0 [1.4–5.2] | 0.08 (<0.0001) | 0.2 (<0.0001) | 0.4 (0.04) |

| DHEAS/DHEA | 73 [38–92] | 223 [140–382] | 0.3 (<0.0001) | 2.5 [2.0–3.6] | 163 [120–263] | 0.01 (<0.0001) | 0.04 (<0.0001) | 0.7 (0.1) |

| DHEAS/PregS | 24 [12–49] | 36 [28–62] | 0.7 (0.07) | 1.3 [0.8–2.7] | 22 [14–32] | 0.07 (<0.0001) | 0.05 (<0.0001) | 0.6 (0.003) |

| DHEA/Preg | 13 [9.5–20] | 6.9 [4.6–9.1] | 1.9 (0.003) | 1.2 [0.7–1.9] | 4.4 [2.8–8.7] | 0.3 (<0.0001) | 0.1 (<0.0001) | 0.8 (0.1) |

LC-MS/MS was used to quantify the unconjugated Δ5 steroids and steroid sulfates in paired AV and the IVC before and after 10 to 30 minutes of cosyntropin administration (injected as a 0.125-mg bolus followed by a 0.125-mg/h continuous infusion). Data are expressed as median [interquartile range]. AV/IVC is expressed as median of individual ratios with [interquartile range]. Statistical significance was determined by paired t test (P < 0.05). To convert nmol/L to ng/dL, multiply by the following correction factors: Preg, 31.65; 17OHPreg, 33.25; DHEA, 28.84; PregS, 39.65; 17OHPregS, 41.25; DHEAS, 36.85; and AdiolS, 37.05.

Of the unconjugated Δ5-steroids measured, DHEA was most abundant at baseline, followed by 17OHPreg and Preg in both the AV and the IVC (Table 1). As observed with steroid sulfates, Preg responded sharply to cosyntropin (578-fold in the AV compared with baseline) and reached concentrations similar to those of DHEA in the AV samples (Supplemental Fig. 1 (438.6KB, docx) ; Table 1).

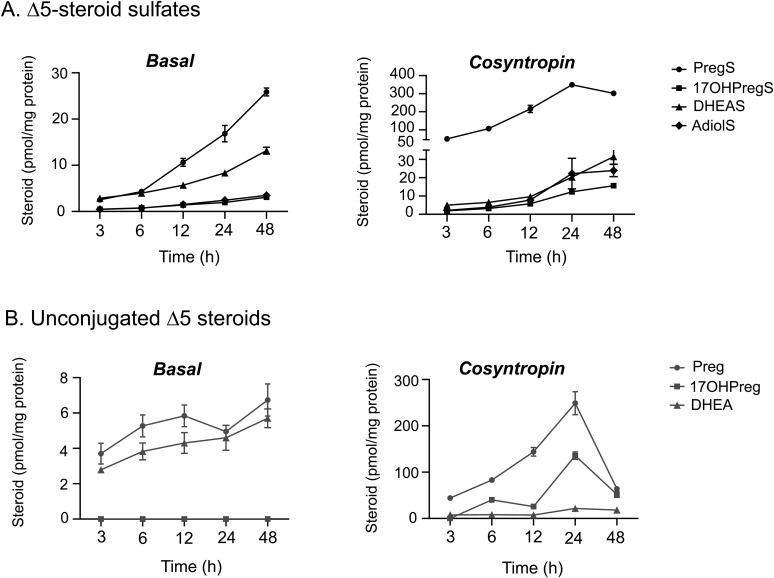

Human adrenal cell production of Δ5-steroid sulfates

To examine the adrenal production of Δ5-steroid sulfates at a cellular level, we quantified these steroids in media from cultivated human adrenocortical cells under basal and cosyntropin-stimulated conditions (Fig. 2). We found that of the steroids measured, PregS accumulated at the highest rate, both under basal conditions and after cosyntropin stimulation (Fig. 2). After cosyntropin treatment, PregS and Preg demonstrated abrupt acute responses (21- and 12-fold increase at 3 hours compared with baseline, respectively; P < 0.05) and peaked after 24 hours. In contrast, DHEAS and DHEA responded only modestly to cosyntropin stimulation (1.8- and 2.8-fold increase at 3 hours compared with baseline, respectively; P < 0.05). By 48 hours after cosyntropin stimulation, we detected a modest decline in PregS levels and a steep drop in Preg content, whereas the DHEAS level continued to rise slightly (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Steroid concentrations under basal and cosyntropin-stimulated conditions in human adrenal cells. Steroid sulfates and unconjugated Δ5-steroids were quantified in media from cultivated human adrenal cortical cells under basal and cosyntropin-stimulated (10 nM) conditions for the indicated time points. The steroid content of media was measured using LC-MS/MS and was normalized with the cellular protein content. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Adrenal zonal content of Δ5-steroid sulfates

To further understand the intra-adrenal biosynthesis of Δ5-steroid sulfates, we measured their content in microdissected ZF and ZR samples. We found that PregS and 17OHPregS were present in similar amounts in both adrenal zones, whereas DHEAS and AdiolS were found predominantly in the ZR (Table 2). We observed that DHEAS was the most abundant steroid in the ZR, followed by AdiolS, PregS, and 17OHPregS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sulfated Δ5-Steroid Content in Human Adrenal ZF and ZR

| Steroid (pg/mg Protein) | ZF | ZR | Fold Change (ZR/ZF) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PregS | 1826 [1151–5213] | 1244 [1052–7555] | 0.7 | 0.35 |

| 17OHPregS | 739.6 [428–1521] | 516.9 [432–1993] | 0.7 | 0.70 |

| DHEAS | 1704 [1238–4076] | 7074 [3890–10858] | 4.2 | 0.03 |

| AdiolS | 1290 [943–1630] | 4874 [2924–7397] | 3.8 | 0.03 |

Human adrenal ZF and ZR tissues were isolated by visual microdissection (n = 5 adrenals). The Δ5-steroid sulfate content of ZF and ZR tissue was measured by LC-MS/MS. Steroid concentrations were normalized to total tissue protein content. Data are expressed as median [interquartile range]. Statistical significance was determined by paired t test (P < 0.05).

Human P450 17A1 activity assays

The steady-state turnovers of PregS and 17OHPregS were examined at various substrate concentrations (0.05 to 800 μM) in a reconstituted system containing purified P450 17A1 and POR, in the absence or presence of CYB5A. All reactions were performed in parallel with Preg and 17OHPreg (0.05 to 80 μM) under the same experimental conditions. We found no detectable metabolism of either of the two steroid sulfates by P450 17A1. In contrast, Preg and 17OHPreg were both metabolized by P450 17A1, and CYB5A greatly amplified the lyase reaction (40-fold). These results are summarized in Supplemental Table 2 (438.6KB, docx) .

Discussion

Herein, we have comprehensively analyzed the human adrenal synthesis of four Δ5-steroid sulfates. In addition to DHEAS—a major and extensively studied adrenal steroid (28–31), we dissected the dynamic regulation of three other Δ5-steroid sulfates, PregS, 17OHPregS, and AdiolS, in vivo and in vitro. Although DHEAS remains the most abundant steroid in the peripheral circulation with established diagnostic utility for several adrenal disorders, PregS and AdiolS have recently emerged as biomarkers with promising clinical applications (18–20). To properly use these steroid sulfates in the study and diagnosis of adrenal pathology, an understanding of their adrenal synthesis patterns and response to ACTH is essential.

A key finding of our studies is the marked acute rise of PregS (and 17OHPregS to a lesser extent) in response to cosyntropin stimulation, both in AV samples and in cultured adrenal cells, which is in stark contrast to DHEAS and AdiolS. PregS has been shown to function as a neurosteroid, targeting various ion channels, enzymes, and transporters (4, 5, 32). As a biomarker for adrenal function, however, PregS remains understudied. We recently found that patients with classic 21OHD had approximately threefold higher circulating PregS concentrations than sex- and age-matched controls (18). Furthermore, in a study of 114 children and adults with classic 21OHD, PregS was significantly higher in males with testicular adrenal rest tumors and in women with menstrual disorders and/or hirsutism (19). Such clinical findings typically reflect poor long-standing disease control and presumably higher cumulative ACTH stimulation. Conversely, DHEAS and AdiolS were paradoxically lower in patients with classic 21OHD (17, 18) than in healthy individuals and were also similar between males with 21OHD with and without testicular adrenal rest tumors (19). In this study, we found that PregS correlated tightly with ACTH, whereas DHEAS showed no significant correlation. To further understand these initial findings, we evaluated the effect of ACTH on adrenal-derived Δ5-steroid sulfates in vivo and in vitro.

Our studies of AV samples showed a dramatic increment of PregS and 17OHPregS after cosyntropin stimulation, whereas DHEAS responded modestly. Remarkably, although DHEAS is the dominant steroid under basal conditions in both the AV and IVC, cosyntropin-stimulated concentrations of PregS attained in the AV approached those of DHEAS. Owing to its lower rate of clearance and lack of diurnal rhythm, DHEAS has long been regarded as a reflection of chronic adrenal cortex function. To this end, concentrations of DHEAS in the AV and IVC and their relationships with cosyntropin stimulation have been previously assessed (28–31, 33–35). Although studies implementing immunoassays suggested a robust response of DHEAS to cosyntropin stimulation (30), more recent LC-MS/MS studies have demonstrated a modest gradient between AV and peripheral serum, both with and without cosyntropin administration, in concordance with our findings (31, 36). The half-life of DHEAS (7 to 10 hours) is estimated to be 3.5 to 5 times greater than that of PregS (∼2.2 hours) (37, 38), which could account for the fact that PregS concentrations in the peripheral circulation were not maintained at levels comparable to those of DHEAS. Paradoxically, circulating concentrations of PregS rose more than twofold after cosyntropin, despite a 32-fold upsurge of PregS in the AV samples, which might reflect a large volume of distribution due to dilution, robust tissue uptake, and clearance. Relative to their respective sulfated derivatives, the AV concentrations of unconjugated Δ5-steroids Preg, 17OHPreg, and DHEA demonstrated steeper surges after cosyntropin stimulation, in concordance with previous findings (30, 31, 35).

To circumvent the half-life differences observed in vivo, we analyzed the response of Δ5-steroid sulfates to immediate and sustained cosyntropin stimulation in cultured human adrenal cells. Under basal conditions, PregS was the most abundantly produced steroid of those measured (rising 10-fold from 3 to 48 hours), whereas all other steroids demonstrated more gradual increments. The effect of cosyntropin on PregS in adrenal cells mirrored the in vivo response observed during AV sampling. In addition, we found that PregS not only responded rapidly to cosyntropin but continued rising for 24 hours; overall, peak PregS concentrations were >30-fold higher than those of all other steroid sulfates. Similar responses of steroid sulfates were noted in an ACTH-responsive H295RA cell line recently developed by our group (39). Of the unconjugated Δ5-steroids, Preg and DHEA were highest at baseline, whereas Preg demonstrated the sharpest response to cosyntropin. A decline in downstream steroidogenic enzymes from ACTH deprivation between organ collection and cosyntropin treatment might have influenced our results; however, previous studies of unconjugated steroid synthesis in human adrenal cells showed stimulation of the steroidogenic flux by cosyntropin at several levels, with predominance of cortisol (26, 40).

Our data question how efficiently Preg is converted to cortisol in the ZF during acute ACTH stimulation. Unconjugated steroid precursors circulate at concentrations one to two orders of magnitude lower than that of cortisol, consistent with limited diversion of steroids to unproductive pathways. The production of PregS and 17OHPregS represent competitions between 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD3B2) and SULT2A1 or P450 17A1 for nascent Preg and 17OHPreg. In the ZR, where P450 17A1 and CYB5A are abundant and HSD3B2 is low, the pathway primarily follows P450 17A1 to DHEA followed by sulfonation. Despite abundant HSD3B2 expression in the ZF, our data suggest that a substantial amount of nascent Preg and 17OHPreg is lost to cortisol synthesis via sulfonation, attesting to the catalytic capacity of SULT2A1 in the ZF and the minimal effect of ACTH on HSD3B2 expression (41).

To understand the intra-adrenal flux of Δ5-steroid sulfates, we assessed their content within the adjacent ZF and ZR. Although DHEAS and AdiolS were found solely in the ZR, PregS and 17OHPregS were equally present in both the ZF and the ZR. Transcriptome comparison between the two adrenal zones has shown that the expression of SULT2A1 is much higher in the ZR than in the ZF (22). Studies in fetal adrenal cells have demonstrated that SULT2A1 expression and DHEAS synthesis increase in response to ACTH (42). The acute burst of Preg substrate that occurs in response to ACTH stimulation might explain the abrupt surge in PregS, despite lower SULT2A1 expression in ZF.

Although steroid sulfates are largely thought to be generated by sulfonation of their respective unconjugated Δ5-steroids by sulfotransferase, studies conducted in the 1960s proposed a direct unidirectional pathway of sulfated steroids, from PregS → 17OHPregS → DHEAS (43–47). A more recent study using bovine P450 17A1 proposed that 17OHPregS can derive from PregS, whereas an enzymatic conversion of 17OHPregS to DHEAS was not observed (48). A subsequent, less-detailed study using human P450 17A1 found a 15% conversion of 40 μM PregS to 17OHPregS in a similar in vitro system. Contrary to these investigations, we did not detect any significant production of 17OHPregS from PregS by purified human P450 17A1, even when concentrations as high as 800 μM were used. Our results are consistent with findings that despite a threefold elevation of PregS in patients with 21OHD compared with age- and sex-matched controls, 17OHPregS remained similar between the two groups (18). We cannot exclude a contribution from differences in reconstitution conditions as a reason for our discordant results with prior studies, but we conclude that any P450 17A1–catalyzed metabolism of PregS is small compared with its metabolism of Preg.

In summary, we simultaneously quantified the baseline and cosyntropin-stimulated production of PregS, 17OHPregS, DHEAS, and AdiolS by the human adrenal both in vivo and in vitro. The acute and sharp response of PregS to cosyntropin stimulation suggests that PregS can be used to acutely interrogate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and serve as biomarker in various adrenal disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. James Shields, Department of Radiology, University of Michigan, who performed AV sampling; Carole Ramm, Timothy Muth, and David Madrigal for assistance with sample procurement and regulatory management of clinical research protocols; Dr. Sunil K. Upadhyay for the synthesis of PregS, 17OHPregS, and AdiolS; Mr. Robert Chomic (Michigan Metabolomics and Obesity Center, University of Michigan) for technical assistance with liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; Gift of Life, Michigan; and all study participants.

Financial Support: This work was supported by Grants 1K08DK109116, Pepper Center AG-024824/Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research UL1TR000433 (to A.F.T.); R01DK069950 and R01DK43140 (to W.E.R.); and R01GM086596 (to R.J.A.). J. Rege is supported by the Postdoctoral Translational Scholars Program fellowship award 2UL1TR000433 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. Mass spectrometry used core services supported by Grant DK089503 from the National Institutes of Health to the University of Michigan under the Michigan Nutrition Obesity Research Center.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- 17OHPreg

- 17α-hydroxypregnenolone

- 17OHPregS

- 17α-hydroxypregnenolone sulfate

- 21OHD

- 21-hydroxylase deficiency

- ACTH

- adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AdiolS

- 5-androstenediol-3-sulfate

- AV

- adrenal vein

- CYB5A

- cytochrome b5 type A

- DHEA

- dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEAS

- dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- DMEM

- Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- HSD3B2

- 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2

- IVC

- inferior vena cava

- LC-MS/MS

- liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- POR

- cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase

- Preg

- pregnenolone

- PregS

- pregnenolone sulfate

- SULT2A1

- sulfotransferase type 2A

- ZF

- zona fasciculata

- ZR

- zona reticularis.

References

- 1.Strott CA. Steroid sulfotransferases. Endocr Rev. 1996;17(6):670–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kauffman FC. Sulfonation in pharmacology and toxicology. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(3-4):823–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs TT, Russek SJ, Farb DH. Sulfated steroids as endogenous neuromodulators. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84(4):555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostakis E, Smith C, Jang MK, Martin SC, Richards KG, Russek SJ, Gibbs TT, Farb DH. The neuroactive steroid pregnenolone sulfate stimulates trafficking of functional N-methyl D-aspartate receptors to the cell surface via a noncanonical, G protein, and Ca2+-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84(2):261–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harteneck C. Pregnenolone sulfate: from steroid metabolite to TRP channel ligand. Molecules. 2013;18(10):12012–12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noordam C, Dhir V, McNelis JC, Schlereth F, Hanley NA, Krone N, Smeitink JA, Smeets R, Sweep FC, Claahsen-van der Grinten HL, Arlt W. Inactivating PAPSS2 mutations in a patient with premature pubarche. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2310–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oostdijk W, Idkowiak J, Mueller JW, House PJ, Taylor AE, O’Reilly MW, Hughes BA, de Vries MC, Kant SG, Santen GW, Verkerk AJ, Uitterlinden AG, Wit JM, Losekoot M, Arlt W. PAPSS2 deficiency causes androgen excess via impaired DHEA sulfation: in vitro and in vivo studies in a family harboring two novel PAPSS2 mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):E672–E680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leowattana W. DHEAS as a new diagnostic tool. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341(1-2):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longcope C. Dehydroepiandrosterone metabolism. J Endocrinol. 1996;150(Suppl):S125–S127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischli S, Jenni S, Allemann S, Zwahlen M, Diem P, Christ ER, Stettler C. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in the assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(2):539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasrallah MP, Arafah BM. The value of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate measurements in the assessment of adrenal function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(11):5293–5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayyed Kassem L, El Sibai K, Chaiban J, Abdelmannan D, Arafah BM. Measurements of serum DHEA and DHEA sulphate levels improve the accuracy of the low-dose cosyntropin test in the diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):3655–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennedy MC, Annamalai AK, Prankerd Smith O, Freeman N, Vengopal K, Graggaber J, Koulouri O, Powlson AS, Shaw A, Halsall DJ, Gurnell M. Low DHEAS: a sensitive and specific test for detection of subclinical hypercortisolism in adrenal incidentalomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;102(3):786–792j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yener S, Yilmaz H, Demir T, Secil M, Comlekci A. DHEAS for the prediction of subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: perplexing or advantageous? Endocrine. 2015;48(2):669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaiani E, Maceiras M, Chaler E, Lazzati JM, Chiavero M, Novelle C, Rivarola M, Belgorosky A. Central adrenal insufficiency could not be confirmed by measurement of basal serum DHEAS levels in pubertal children. Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;82(5):332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bencsik Z, Szabolcs I, Kovács Z, Ferencz A, Vörös A, Kaszás I, Bor K, Gönczi J, Góth M, Kovács L, Dohán O, Szilágyi G. Low dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) level is not a good predictor of hormonal activity in nonselected patients with incidentally detected adrenal tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(5):1726–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rezvani I, Garibaldi LR, Digeorge AM, Artman HG. Disproportionate suppression of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) in treated patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 1983;17(2):131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turcu AF, Nanba AT, Chomic R, Upadhyay SK, Giordano TJ, Shields JJ, Merke DP, Rainey WE, Auchus RJ. Adrenal-derived 11-oxygenated 19-carbon steroids are the dominant androgens in classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(5):601–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turcu AF, Mallappa A, Elman MS, Avila NA, Marko J, Rao H, Tsodikov A, Auchus RJ, Merke DP. 11-Oxygenated androgens are biomarkers of adrenal volume and testicular adrenal rest tumors in 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(8):2701–2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rege J, Karashima S, Lerario AM, Smith JM, Auchus RJ, Kasa-Vubu JZ, Sasano H, Nakamura Y, White PC, Rainey WE. Age-dependent increases in adrenal cytochrome b5 and serum 5-androstenediol-3-sulfate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(12):4585–4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassett MH, Suzuki T, Sasano H, De Vries CJ, Jimenez PT, Carr BR, Rainey WE. The orphan nuclear receptor NGFIB regulates transcription of 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. implications for the control of adrenal functional zonation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(36):37622–37630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rege J, Nakamura Y, Wang T, Merchen TD, Sasano H, Rainey WE. Transcriptome profiling reveals differentially expressed transcripts between the human adrenal zona fasciculata and zona reticularis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):E518–E527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimoto FK, Peng HM, Zhang H, Anderson SM, Auchus RJ. Epoxidation activities of human cytochromes P450c17 and P450c21. Biochemistry. 2014;53(48):7531–7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng HM, Im SC, Pearl NM, Turcu AF, Rege J, Waskell L, Auchus RJ. Cytochrome b5 activates the 17,20-lyase activity of human cytochrome P450 17A1 by increasing the coupling of NADPH consumption to androgen production. Biochemistry. 2016;55(31):4356–4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulrooney SB, Waskell L. High-level expression in Escherichia coli and purification of the membrane-bound form of cytochrome b(5). Protein Expr Purif. 2000;19(1):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turcu AF, Rege J, Chomic R, Liu J, Nishimoto HK, Else T, Moraitis AG, Palapattu GS, Rainey WE, Auchus RJ. Profiles of 21-carbon steroids in 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2283–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima M, Yamato S, Shimada K. Determination of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate in biological samples by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry using [7,7,16,16-2H4]-dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate as an internal standard. Biomed Chromatogr. 1998;12(4):211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valenta LJ, Elias AN. Steroid hormones in the adrenal venous effluents in idiopathic hirsutism under basal and stimulated conditions. Horm Metab Res. 1986;18(10):710–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munabi AK, Feuillan P, Staton RC, Rodbard D, Chrousos GP, Anderson RE, Strober MD, Loriaux DL, Cutler GB Jr. Adrenal steroid responses to continuous intravenous adrenocorticotropin infusion compared to bolus injection in normal volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(4):1036–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rege J, Nakamura Y, Satoh F, Morimoto R, Kennedy MR, Layman LC, Honma S, Sasano H, Rainey WE. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of human adrenal vein 19-carbon steroids before and after ACTH stimulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1182–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peitzsch M, Dekkers T, Haase M, Sweep FC, Quack I, Antoch G, Siegert G, Lenders JW, Deinum J, Willenberg HS, Eisenhofer G. An LC-MS/MS method for steroid profiling during adrenal venous sampling for investigation of primary aldosteronism. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;145:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horak M, Vlcek K, Chodounska H, Vyklicky L Jr. Subtype-dependence of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor modulation by pregnenolone sulfate. Neuroscience. 2006;137(1):93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moltz L, Pickartz H, Sörensen R, Schwartz U, Hammerstein J. Ovarian and adrenal vein steroids in seven patients with androgen-secreting ovarian neoplasms: selective catheterization findings. Fertil Steril. 1984;42(4):585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moltz L, Schwartz U, Sörensen R, Pickartz H, Hammerstein J. Ovarian and adrenal vein steroids in patients with nonneoplastic hyperandrogenism: selective catheterization findings. Fertil Steril. 1984;42(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenhofer G, Dekkers T, Peitzsch M, Dietz AS, Bidlingmaier M, Treitl M, Williams TA, Bornstein SR, Haase M, Rump LC, Willenberg HS, Beuschlein F, Deinum J, Lenders JW, Reincke M. Mass spectrometry-based adrenal and peripheral venous steroid profiling for subtyping primary aldosteronism. Clin Chem. 2016;62(3):514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhofer G, Peitzsch M, Kaden D, Langton K, Pamporaki C, Masjkur J, Tsatsaronis G, Mangelis A, Williams TA, Reincke M, Lenders JWM, Bornstein SR. Reference intervals for plasma concentrations of adrenal steroids measured by LC-MS/MS: impact of gender, age, oral contraceptives, body mass index and blood pressure status. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;470:115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baulieu EE. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): a fountain of youth? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3147–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buster JE, Abraham GE, Kyle FW, Marshall JR. Serum steroid levels following a large intravenous dose of a steroid sulfate precursor during the second trimester of human pregnancy: II. pregnenolone sulfate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1974;38(6):1038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanba K, Chen AX, Turcu AF, Rainey WE. H295R expression of melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein results in ACTH responsiveness. J Mol Endocrinol. 2016;56(2):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing Y, Edwards MA, Ahlem C, Kennedy M, Cohen A, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Rainey WE. The effects of ACTH on steroid metabolomic profiles in human adrenal cells. J Endocrinol. 2011;209(3):327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing Y, Parker CR, Edwards M, Rainey WE. ACTH is a potent regulator of gene expression in human adrenal cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2010;45(1):59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sirianni R, Mayhew BA, Carr BR, Parker CR Jr, Rainey WE. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and urocortin act through type 1 CRH receptors to stimulate dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate production in human fetal adrenal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5393–5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Včeláková H, Hill M, Lapcík O, Parízek A. Determination of 17alpha-hydroxypregnenolone sulfate and its application in diagnostics. Steroids. 2007;72(4):323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Killinger DW, Solomon S. Synthesis of pregnenolone sulfate, dehydroisoandrosterone sulfate, 17-alpha-hydroxypregnenolone sulfate and delta-5-pregnenetriol sulfate by the normal human adrenal gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1965;25(2):290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calvin HI, Lieberman S. Evidence that steroid sulfates serve as biosynthetic intermediates: II. in vitro conversion of pregnenolone-3H sulfate-35S to 17alpha-hydroxypregnenolone-3H sulfate-35S. Biochemistry. 1964;3(2):259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calvin HI, Vandewiele RL, Lieberman S. Evidence that steroid sulfates serve as biosynthetic intermediates: in vivo conversion of pregnenolone-sulfate-S35 to dehydroisoandrosterone sulfate-S35. Biochemistry. 1963;2(4):648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calvin HI, Lieberman S. Studies on the metabolism of pregnenolone sulfate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1966;26(4):402–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neunzig J, Sanchez-Guijo A, Mosa A, Hartmann MF, Geyer J, Wudy SA, Bernhardt R. A steroidogenic pathway for sulfonated steroids: the metabolism of pregnenolone sulfate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144(Pt B):324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]