Abstract

The YOUNG‐MI registry is a retrospective study examining a cohort of young adults age ≤ 50 years with a first‐time myocardial infarction. The study will use the robust electronic health records of 2 large academic medical centers, as well as detailed chart review of all patients, to generate high‐quality longitudinal data regarding the clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age. Our findings will provide important insights regarding prevention, risk stratification, treatment, and outcomes of cardiovascular disease in this understudied population, as well as identify disparities which, if addressed, can lead to further improvement in patient outcomes.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Gender, Ischemic Heart Disease, Myocardial Infarction, Preventive Cardiology, Young Adults

1. INTRODUCTION

Significant advances in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) have led to a large reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events as well as CV mortality.1 However, the same reduction in CV events has not been witnessed in young adults,2 and CVD remains a major cause of death among young individuals around the world.3

Over the past decade, the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (MI) among persons age < 55 years has remained stable.2 With increasing rates of traditional CV risk factors such as diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, especially among adolescents, it is likely that coronary artery disease (CAD) will become even more prevalent in this age group.4, 5, 6, 7 Furthermore, considerable challenges exist in prevention of CAD among young individuals, as significant proportions are unaware of their risk factors.8 Current risk calculators—which are based on older populations—are less applicable to younger patients, especially those age < 40 years.9 When young adults, especially females, experience symptoms of CAD, they may be more likely to have atypical symptoms, leading to delays in presentation or treatment.10 Finally, young adults may have higher rates of medication nonadherence.11

The burden of CAD in the young is an important public‐health issue given the negative impact on physical, mental, social, and financial health, and greater healthcare utilization among affected individuals. Therefore, we set out to assess the demographics, clinical characteristics, quality of care received, and outcomes of young patients presenting with a first‐time MI.

2. STUDY OBJECTIVES

The initial objectives of the study are (1) to characterize the presence, awareness, and treatment of CV risk factors among young patients admitted with MI; (2) to determine how contemporary risk scores perform in risk‐stratifying young individuals with MI; (3) to characterize presenting symptoms as well as time to presentation among young individuals with MI; (4) to determine the frequency and prognosis of type 1 and type 2 MI in young individuals; (5) to investigate differences and disparities in presentation, management, and outcomes of MI in young individuals by age, sex, and race; (6) to characterize invasive angiography findings among young individuals with MI; (7) to characterize noninvasive cardiac imaging test findings prior to MI; and (8) to identify predictors of in‐hospital, 1‐year, and long‐term outcomes among young individuals with MI.

3. METHODS

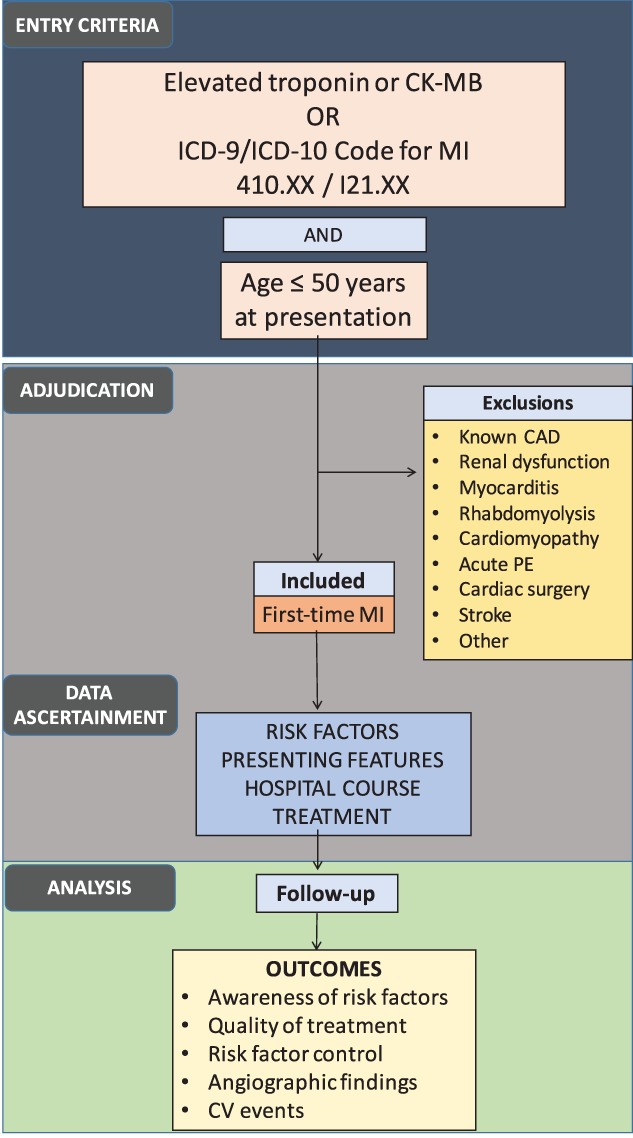

The YOUNG‐MI registry is a dynamic registry of young individuals admitted to 2 large academic centers with a first MI. The first phase of the registry will include patients presenting between January 2000 and April 2016. Figure 1 provides an outline of the study design.

Figure 1.

Schema of registry design. Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CK‐MB, creatine kinase MB fraction; CV, cardiovascular; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MI, myocardial infarction

3.1. Data source

The Research Patient Data Registry (RPDR) at Partners HealthCare will serve as the data source for this registry. RPDR extracts clinical data from several hospitals in Partners HealthCare, including Brigham & Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, and stores the data in a single central data warehouse. It provides demographics, diagnoses, laboratory tests, medications, health history, procedures, and clinical notes for individuals meeting specified criteria. RPDR is linked to the Social Security Administration Death Master File and can provide vital status information for all subjects.

The Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board has approved the study in its current form.

3.2. Entry criteria

3.2.1. Identification of potential patients with MI

We will use the RPDR to identify patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) or ICD‐10 diagnoses of acute MI (410.xx, I21.xx) or elevated cardiac biomarkers (troponin [Tn] I or T, or creatine kinase‐MB fraction [CK‐MB]), starting from January 2000. Patients age ≤ 50 years at time of presentation will be included. The RPDR will be queried at various phases to continually add patients to the registry.

Most studies use an age of ≤45 years to describe “young adults” with CVD,12, 13, 14 whereas those with a primary focus on women use an age of ≤55 years as the cutoff.15 Furthermore, data from the past decade have demonstrated that hospitalizations for acute MI increased in absolute numbers for women age < 50 years, but decreased for similarly aged men, and for both sexes 50 to 55 years of age.2 Based on these findings, our study will use an age of ≤50 years to categorize young individuals, regardless of sex.

3.2.2. Adjudication of MI

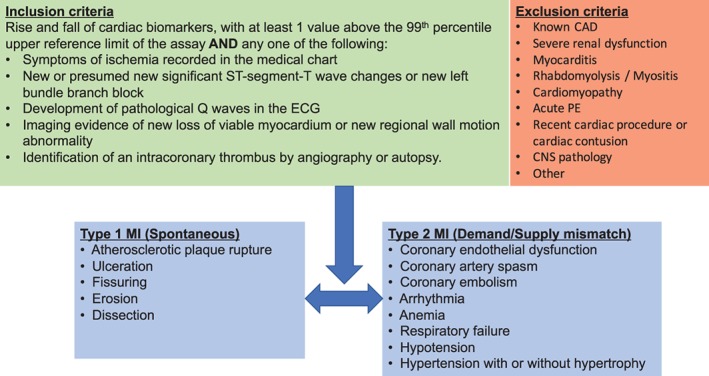

Records of patients who meet entry criteria (patients age ≤ 50 years with potential MI) will be uploaded into our secure, customized electronic adjudication system for review. For each of these patients, all available clinical records from the index admission, including the physician notes, laboratory tests, imaging studies, any procedural results, and discharge summary, will be reviewed to determine the presence and type of MI using the third universal definition of MI (Figure 2).16 Type 1 MI will be defined as an MI related to atherosclerotic plaque rupture, ulceration, fissuring, erosion, or dissection with resulting thrombus. Type 2 MI will be defined in instances where a condition such as coronary endothelial dysfunction, coronary artery spasm, coronary embolism, arrhythmia, anemia, respiratory failure, hypotension, or hypertension contributes to an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. Type 3 MI will be defined as MI resulting in death when biomarkers are unavailable (we anticipate few type 3 MI cases, as our entry criteria are based on elevated biomarkers). Type 4 and type 5 MIs will be excluded, as we are excluding patients with known CAD.16

Figure 2.

Inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and case definition. Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CNS, central nervous system; ECG, electrocardiogram; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism

Cases not determined to have an MI or cases that meet exclusion criteria will be further adjudicated to determine the primary cause of elevated cardiac biomarkers, particularly because younger individuals can have various other conditions that can lead to an elevation of these markers.17 Records will be reviewed by a team of trained study physicians. Cases in which there is uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of MI will be reviewed by the full adjudication committee, with decision reached by consensus.

3.2.3. Inclusion criteria

The study will include individuals presenting with (1) age ≤ 50 years and (2) rise and fall of cardiac biomarkers, with ≥1 value above the upper reference limit of the assay, and any one of the following: (a) symptoms of ischemia recorded in the medical chart; (b) new or presumed new significant ST‐segment T‐wave changes or new left bundle branch block; (c) development of pathologic Q waves on the electrocardiogram; (d) imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall‐motion abnormality; or (e) identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography or autopsy.16

3.2.4. Exclusion criteria

The study will exclude patients with (1) known CAD, defined as prior MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting; (2) severe renal dysfunction, defined as stage 5 chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 15 mL/min/m2), chronic dialysis prior to MI, or prior renal transplantion18; (3) myocarditis, determined by discharge diagnosis as well as review of patient's chart for signs and symptoms consistent with myocarditis, and/or supportive findings on imaging or pathology19; (4) rhabdomyolysis/myositis, determined based on history as well as elevated CK with normal MB fraction20; (5) cardiomyopathy, including known infiltrative cardiomyopathies such as amyloidosis or sarcoidosis, or left ventricular ejection fraction ≤30% prior to MI, or prior cardiac transplantation21, 22; (6) acute pulmonary embolism associated with elevated Tn23; (7) cardiothoracic surgery, cardiac procedure, or chest‐wall trauma within the past 30 days24, 26; (8) central nervous system pathology such as stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or seizures, as elevated cardiac biomarkers can commonly be observed in such settings and have uncertain clinical significance27, 28; and (9) other causes of cardiac biomarker elevation not thought to represent an acute coronary syndrome, such as following a marathon, electrocution, or burns.29, 30, 31

3.3. Ascertainment of clinical data

3.3.1. Presentation

Information on presentation will be collected from the medical chart: whether the patient arrived by ambulance or was transferred from an outside hospital; presenting features, including characteristics of chest pain and associated symptoms; time to presentation; onset of symptoms; delays in presentation; and vital signs at presentation. Stuttering chest pain will be defined as any waxing and waning of chest pain over days leading to the MI. The frequency of anginal events within 24 h prior to admission (when these data are available from admission notes) will be ascertained to calculate risk scores. For patients transferred from an outside hospital, the symptoms and vital signs at presentation to the outside hospital will be recorded from transfer notes.

3.3.2. Hospital course

Each patient's hospital course will be reviewed, including laboratory and both noninvasive and invasive imaging findings. In addition, we will ascertain treatments, including whether coronary revascularization was performed, and we will identify all in‐hospital complications of MI, such as cardiogenic shock; new‐onset heart failure; episodes of sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation; mechanical complications including papillary muscle rupture, interventricular septum rupture, tamponade, or re‐infarctions; and in‐hospital death during the index admission.

3.3.3. Risk factors

Medical records will be reviewed for the presence of CV risk factors and whether they were known prior to admission or diagnosed during hospitalization for MI. To accomplish this, we will review all medical records, when available, prior to hospital admission. Detailed information will be ascertained from all available medical records on traditional and emerging CV risk factors and social history, including substance abuse. DM will be defined as fasting plasma glucose >126 mg/dL, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5%, or diagnosis/treatment for DM. Prediabetes will be defined as fasting plasma glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dL, HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4%, or diagnosis/treatment for prediabetes. Hypertension will be defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or diagnosis/treatment of hypertension. Dyslipidemia will be defined as total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, serum triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dL in men or <50 mg/dL in women, or diagnosis/treatment of dyslipidemia. Familial hypercholesterolemia will be defined as documented causative mutations in LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9 genes, or meeting Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria for definite or probable familial hypercholesterolemia.32 Chronic kidney disease will be defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate between 60 and 15 mL/min/m2 prior to admission or a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Peripheral artery disease will be defined as prior peripheral arterial revascularization or a diagnosis of peripheral artery disease or limb claudication. Smoking will be defined as current (tobacco products used within the last month), former, or never. Marijuana, cocaine, and intravenous drug use will be defined as use of these substances within the past week, as documented by admission notes or detected on toxicology. A positive family history of CAD will be defined as any first‐degree relative with a history of fatal/nonfatal MI or having undergone coronary revascularization. Family history of premature CAD will be defined as any of the previous occurring before age 55 years for male family members and before age 65 years for female family members.

3.3.4. Medications

Available medical records will be reviewed for prescription of CV medications prior to admission and at discharge. For all lipid‐lowering medications, information on both type and dose of agent will be recorded, to determine whether any changes in these medications reflected intensification of therapy following MI.

3.3.5. Laboratory tests

Laboratory values preadmission, during admission, and post‐discharge will be extracted from RPDR. In anticipation of heterogeneity of varying serum Tn assays across the 2 institutions over time, we will standardize all abnormal values to the upper limit of normal used for each assay.16

3.3.6. Follow‐up

One‐year and longer‐term follow‐up of all subjects included in the registry will be conducted via a review of the electronic medical record system. At each follow‐up, the current health status, status of comorbidities, medication regimen, and any interim CV events will be recorded. Death will be assessed from the Social Security Administration's Death Master File. The National Death Index will be queried for cases in which cause of death or date of death is not available.

3.4. Study endpoints

The following will be assessed:

Presence, awareness, and treatment of traditional CV risk factors upon admission.

Medical therapies prescribed upon discharge following MI.

Modification of risk factors 1 year post‐MI, including low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, weight, and blood pressure.

Invasive angiographic findings.

Adverse CV outcomes at 1 year post‐MI, including CV death, nonfatal MI, stroke, coronary revascularization, peripheral revascularization, hospitalizations, emergency department visits for chest pain/unstable angina, and hospitalizations for heart failure.

Cause of death will be adjudicated independently by 2 cardiologists. Cases in which there is disagreement will be reviewed by the full adjudication committee, with decision reached by consensus. Death will be classified in primarily 1 of 3 categories: (1) CV death, (2) non‐CV death, or (3) undetermined cause of death. The priority will be to distinguish CV deaths from non‐CV deaths. Causes of CV deaths include coronary heart disease deaths defined as death from a CV cause within 30 days of acute MI, heart failure, sudden cardiac death, ischemic stroke, nontraumatic hemorrhagic stroke, immediate complications of a CV procedure, CV hemorrhage, and other CV causes such as pulmonary embolism or peripheral arterial disease. The definition of CV death was adapted from the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association key data elements and definitions for CV endpoint events in clinical trials.33 Death certificates will be requested to determine the cause of death in cases without sufficient information.

3.5. Data management

Study‐related data for all patients who meet inclusion criteria will be stored on REDCap tools hosted by Partners HealthCare Research Computing, Enterprise Research Infrastructure & Services group. REDCap is an encrypted, secure, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant web platform for electronic data capture and serves as an intuitive interface to enter data with real‐time validation (automated data type and range checks). This platform offers easy data manipulation with audit trails and reports for monitoring and querying participant records.34

3.5.1. Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics will be compared across different subgroups, including sex, race, socioeconomic status, and type of MI. Continuous variables will be reported as means or medians and compared with t tests, Wilcoxon rank‐sum, or analysis of variance, as appropriate. Categorical variables will be reported as frequencies and proportions and will be compared with χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Ordinal variables will be compared with a trend test. Regression modeling will be performed to adjust for differences and confounding and to examine relationships between different subgroups. Cox proportional‐hazards modeling will be performed for time‐to‐event analyses. Supervised and unsupervised machine‐learning algorithms will be used for predictive modeling and will be compared with traditional statistical approaches. All analyses will be performed on de‐identified data.

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the important decrease in CVD in most age groups,35, 36 numerous reports highlight the increasing numbers of young adults with CVD. Recent analyses from the National Inpatient Sample have found increasing CV risk factors,2, 37 increasing prevalence of ischemic stroke,37 and stable rates of acute MI hospitalization in young adults.2

The YOUNG‐MI registry will provide real‐world longitudinal clinical data on young individuals with premature CAD presenting with a first MI. Physician review of all cases will generate high‐quality patient‐level data. The longitudinal design will enable follow‐up of long‐term outcomes and trajectories of comorbidities in these individuals. Data generated will complement those from other studies in this field, such as the Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients (VIRGO). VIRGO is a prospective study that has provided valuable insights into young women (and men) with MI.15 However, this study was less likely to include sicker patients or those who died during their hospital course. Consequently, mortality over the 1 year of follow‐up in VIRGO was low, providing limited power for analyses of this outcome.38

Currently available risk calculators are reported to overestimate risk in most individuals,39 but even these likely underestimate risk among young individuals.40 Most young patients do not cross the threshold for primary prevention defined by current guidelines, and consequently they are not considered candidates for preventive therapies. The underestimation of CV risk among young individuals, and subsequent failure to prevent events, is even more concerning given the impact of CVD on loss of lifetime productivity and increased lifetime healthcare utilization. Results from this registry may be used to improve the calibration of existing risk calculators or inform future risk‐prediction models designed specifically for young individuals.

Although most CVD prevention trials have excluded young individuals, the ongoing Eliminate Coronary Artery Disease (ECAD) clinical trial (http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02245087) is recruiting young adults with 1 CV risk factor and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol >70 mg/dL who do not meet guideline‐based treatment thresholds. This trial will test whether low‐dose atorvastatin will lead to a reduction in CV events compared with guideline‐based care over 8 to 10 years of follow‐up. Ultimately, results from our registry may provide data on how to better recognize risk among young individuals.

4.1. Study limitations

This will be a retrospective study analyzing patient encounters over the past 16 years. The long time span introduces variability, as the disease definitions, laboratory assays, and clinical practice have changed over time. The retrospective nature also introduces inherent biases, and although multivariable models will be used to adjust for known confounders, unmeasured and residual confounding will still exist. As the study is limited to 2 large academic centers in one region, results may not be fully generalizable to other practice settings or other regions. Although we will rely on retrospective data, a strength of our study is that we will conduct individual chart review of all patients, rather than relying on coded or administrative data fields. In addition, because all patients who experience an MI are admitted to the hospital and have a detailed history and physical, which includes a thorough assessment of their past medical and social history, we anticipate having comprehensive data available for most patients for the index admission.

5. CONCLUSION

The YOUNG‐MI registry is a large, retrospective analysis of a cohort of young men and women presenting with a first MI. By combining data from our robust electronic health records and performing individual chart reviews, we will have comprehensive data that will allow us to characterize differences in the presence, awareness, and treatment of risk factors, as well as long‐term CV outcomes. Finally, results from our registry may provide data on how to improve risk assessment among young individuals, as well as identify disparities in outcomes and processes of care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Shawn Murphy, Henry Chueh, Stacey Duey, Lynn Simpson, and the Partners HealthCare Research Patient Data Registry and Partners HealthCare Research Computing, Enterprise Research Infrastructure & Services groups for their support.

Conflicts of interest

Deepak L. Bhatt has served on advisory boards for Cardax, Elsevier PracticeUpdate Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, and Regado Biosciences; has served on the board of directors for Boston VA Research Institute and Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care; has been chair of the American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; has served on data monitoring committees for Cleveland Clinic, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Population Health Research Institute; has received honoraria from American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org), Belvoir Publications (editor in chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees), Harvard Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), HMP Communications (editor in chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (guest editor, associate editor), Population Health Research Institute (clinical trial steering committee), Slack Publications (chief medical editor, Cardiology Today's Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (secretary/treasurer), and WebMD (CME steering committees); has served as deputy editor for Clinical Cardiology, chair of the NCDR‐ACTION Registry Steering Committee, and chair of VA CART Research and Publications Committee; has received research funding from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Eisai, Ethicon, Forest Laboratories, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis, and The Medicines Company; has received royalties from Elsevier (editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease); has served as site co‐investigator for Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude Medical (now Abbott); has served as trustee for the American College of Cardiology; and reports unfunded research from FlowCo, Merck, PLx Pharma, and Takeda. Ron Blankstein has served on the advisory board for Amgen, Inc., and has received research support from Amgen, Inc., and Gilead Sciences, Inc. Petr Jarolim has received research support through his institution from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, LP, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Merck & Co., Inc., Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Takeda Global Research and Development Center, and Waters Technologies Corporation. Ankur Gupta is supported by National Institutes of Health grant no. 5T32HL094301‐07. The authors declare no other potential conflicts of interest.

Singh A., Collins B., Qamar A., et al. Study of young patients with myocardial infarction: Design and rationale of the YOUNG‐MI Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:955–961. 10.1002/clc.22774

REFERENCES

- 1. Eisen A, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E. Updates on acute coronary syndrome: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:718–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gupta A, Wang Y, Spertus JA, et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015;132:1667–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poon VT, Kuk JL, Ardern CI. Trajectories of metabolic syndrome development in young adults. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Otaki Y, Gransar H, Cheng VY, et al. Gender differences in the prevalence, severity, and composition of coronary artery disease in the young: a study of 1635 individuals undergoing coronary CT angiography from the prospective, multinational confirm registry. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dabelea D, Mayer‐Davis EJ, Saydah S, et al; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study . Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311:1778–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lloyd A, Steele L, Fotheringham J, et al. Pronounced increase in risk of acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction in younger smokers. Heart. 2017;103:586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, et al. Sex differences in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: a VIRGO study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016. doi: 10.1177/2048872616661847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goff DC, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S74–S75]. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S49–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, et al; NRMI Investigators . Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in‐hospital mortality. JAMA. 2012;307:813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mann DM, Woodard M, Muntner P, et al. Predictors of non‐adherence to statins: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1410–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egred M, Viswanathan G, Davis GK. Myocardial infarction in young adults. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:741–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bangalore S, Fonarow GC, Peterson ED, et al; Get With the Guidelines Steering Committee and Investigators . Age and gender differences in quality of care and outcomes for patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2012;125:1000–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson RE, Pfeffer MA, Thune JJ, et al. High‐risk myocardial infarction in the young: the Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction (VALIANT) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;155:706–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, D'Onofrio G, et al. Variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients (VIRGO) study design. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:684–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelley WE, Januzzi JL, Christenson RH. Increases of cardiac troponin in conditions other than acute coronary syndrome and heart failure. Clin Chem. 2009;55:2098–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freda BJ, Tang WH, Van Lente F, et al. Cardiac troponins in renal insufficiency: review and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feldman AM, McNamara D. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1388–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li SF, Zapata J, Tillem E. The prevalence of false‐positive cardiac troponin I in ED patients with rhabdomyolysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balduini A, Campana C, Ceresa M, et al. Utility of biochemical markers in the follow‐up of heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:3075–3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horwich TB, Patel J, MacLellan WR, et al. Cardiac troponin I is associated with impaired hemodynamics, progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality rates in advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schultz JM, Trunkey DD. Blunt cardiac injury. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Joglar JA, Kowal RC. Electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Clin. 2004;22:101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haegeli LM, Kotschet E, Byrne J, et al. Cardiac injury after percutaneous catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2008;10:273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sandhu R, Aronow WS, Rajdev A, et al. Relation of cardiac troponin I levels with in‐hospital mortality in patients with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:632–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sieweke N, Allendörfer J, Franzen W, et al. Cardiac troponin I elevation after epileptic seizure. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scharhag J, George K, Shave R, et al. Exercise‐associated increases in cardiac biomarkers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bose A, Chhabra CB, Chamania S, et al. Cardiac troponin I: a potent biomarker for myocardial damage assessment following high voltage electric burn. Indian J Plast Surg. 2016;49:406–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murphy JT, Horton JW, Purdue GF, et al. Evaluation of troponin‐I as an indicator of cardiac dysfunction after thermal injury. J Trauma. 1998;45:700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel . Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: Consensus Statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3478a–3490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards) [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:982]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:403–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krumholz HM, Normand SL, Wang Y. Trends in hospitalizations and outcomes for acute cardiovascular disease and stroke, 1999–2011. Circulation. 2014;130:966–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. George MG, Tong X, Kuklina EV, et al. Trends in stroke hospitalizations and associated risk factors among children and young adults, 1995–2008. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. D'Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, et al. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO study. Circulation. 2015;131:1324–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. DeFilippis AP, Young R, Carrubba CJ, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Akosah KO, Schaper A, Cogbill C, et al. Preventing myocardial infarction in the young adult in the first place: how do the National Cholesterol Education Panel III guidelines perform? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1475–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]