Abstract

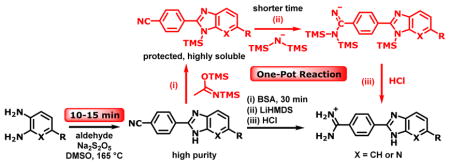

Trimethylsilyl (TMS)-transient protection successfully allowed using Lithium hexamethyldisilazane (LHMDS) to prepare benzimidazole (BI) and 4-azabenzimidazole (azaBI) amidines from nitriles in 58–88% yields. This strategy offers a much better choice to prepare BI/azaBI amidines than the lengthy, low yielding Pinner reaction. Synthesis of aza/benzimidazole rings from aromatic diamines and aldehydes was affected in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in 10–15 min, while known procedures require long time and purification. These methods are important for BI/azaBI-based drug industry and for developing specific DNA binders for expanded therapeutic applications.

Graphical abstract

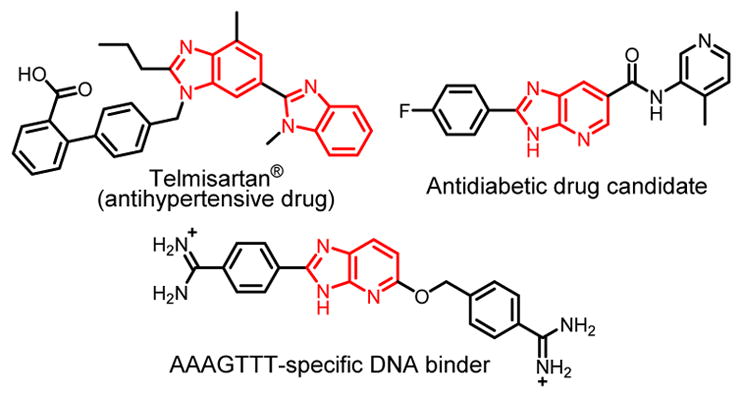

Benzimidazole (BI) constitutes an important scaffold found in over a dozen approved pharmaceuticals.1,2 Additional BI derivatives show potent antiplasmodial,3 antiinflammatory,4 antiviral5 and anticancer activities.6 Derivatives of the BI analogue, 4-azabenzimidazole (azaBI) have recently been studied in animal models and identified as potent anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory,7 and antidiabetic agents8 (Figure 1). Structures containing the BI nucleus can also be used as light-up adenine thymine base pair (AT) specific DNA binders,9 and fluorescent probes in biological systems with potential for developing new biomarkers.10,11 Furthermore, rational design of azaBI-based DNA minor groove binders led to morphing traditional BI recognition of DNA from AT specific12–15 to guanine (G)-containing sequence specific (Figure 1) by introducing the aza group.16–18 This represents a key milestone showing that small molecules can be structured to recognize any given sequence on DNA. Targeting DNA at specific sequences augments a therapeutic strategy of controlling gene expression as a venue for treating many intractable diseases.19,20 DNA minor groove binders, typically, possess positively charged moieties for stronger interaction with the DNA backbone. Among known positively charged groups, amidines are appealing for their excellent cellular and nuclear uptake.12,21 Available methods to prepare amidino BI/azaBI and also to construct substituted BI/azaBI rings, in general, suffer from long reaction time and low efficiency.

Figure 1.

Representative, biologically active BI/azaBI structures.

Amidines are commonly prepared from nitriles by three methods: the Pinner reaction,22 amidoxime method,23 and nucleophilic addition of lithium hexamethyldisilazane24 (LHMDS). The latter approach is the most convenient, because it takes a single step to give the silylated amidines, which provides amidine salts upon HCl workup. It was also adapted to prepare N-substituted amidines25 related to earlier derivatives.26 However, for BI and azaBI systems, LHMDS deprotonates the ring NH, preventing the desired reaction due to a delocalized negative charge on the nitrile. Thus, amidines of such systems are usually prepared by one of the other two methods.27,28 The amidoxime method involves three steps, in which the nitrile is converted to the amidoxime, followed by acetylation to O-acetoxyamidoxime, and then hydrogenolysis to give the amidine. The drawbacks of this method are not only the multistep procedure but also the intermediates are frequently sparingly soluble, leaving the Pinner method, by default, more popular. The Pinner reaction involves two steps: the formation of imidate ester by the action of anhyd HCl-saturated ethanol and conversion to the amidine by ammonia. Low solubility of BI/azaBI molecules leads to long reaction times with the Pinner method, where reactions requiring 3–10 days for each step are commonly encountered.29–32 More problematic is that imidate esters readily hydrolyze to amides,22 which is difficult to avoid during their isolation to remove excess HCl. These facts result in poor yields, and failure of the reaction in some cases.

Herein, we report a novel strategy that allows using LHMDS with BI/azaBI nitriles to make amidines via transient protection of BI/azaBI ring NH in a one-pot procedure. Given the significance of BI/azaBI structure in industry and as biologically active agents, we also present optimized conditions and suggest a mechanism for a facile formation of BI/azaBI rings from aldehydes and diamines in DMSO.

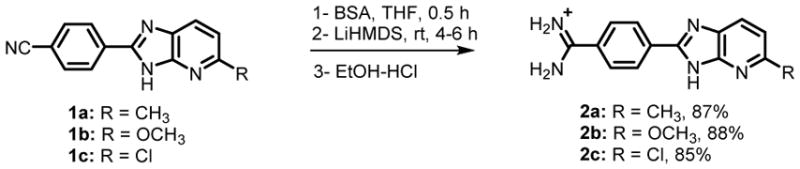

Transient Protection Strategy

The trimethylsilyl group (TMS) has extensively been used in nucleoside chemistry for the Silyl Hilbert-Johnson synthesis,33 and for transient protection of 3′-OH groups.34 We employed N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA) as a mild and efficient reagent35 to transiently protect BI and azaBI ring NH groups with TMS. Thus, suspensions of the azaBI nitrile derivatives 1a–c in THF were treated with BSA for 0.5 h at rt (Scheme 1). The silylation was visually indicated by the homogeneity of the mixture within 5–10 min. Subsequent addition of excess LHMDS led to the consumption of the silylated BI/azaBI nitrile intermediates in 4–6 h. On the other hand, our initial attempts to perform the reaction on Boc-protected 1a resulted in deprotonation of the 5-methyl group as indicated by the maroon color, and cleavage of the Boc group, and failure of the reaction. Thus, it is clear that the methyl on TMS-protected 1a is stable. It is also worth noting that TMS-intermediates enabled highly concentrated reaction solutions, leading to shorter reaction time. In contrast, the reaction of nitriles of Boc-protected indoles, as a suspension in THF, with LHMDS required up to 3 days.27 This demonstrates that our strategy is successful and efficient.

Scheme 1.

One-pot Synthesis of Simple azaBI Amidines

Quenching the reaction with enough HCl to cause desilylation, normally, produces large amounts of NH4Cl due to reaction with excess LHMDS. To avoid this, we first quenched with a stoichiometric amount of an acid to convert LHMDS to hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), which was removed by evaporation. EtOH-HCl was then added to give the amidine salts and remove the TMS transient protection. The salts were precipitated by ether and mixed with water at pH > 9 to give the free bases and to remove inorganic salts. Conversion to the HCl salts and precipitation again gave 2a–c. The resulting amidines were obtained in high yields (85–88%, Scheme 1) and were pure as judged by NMR and elemental analysese. This is highly remarkable because amidines prepared by other methods often require purification by crystallization,36 and chromatography on preparative HPLC,37,38 normal36 or C18 reversed phase38 silica gel.

We made 2a by the amidoxime method in a total yield of 21% (Scheme S1, supporting information), showing that the one-pot LHMDS method is much more efficient in terms of the yield and reaction time.

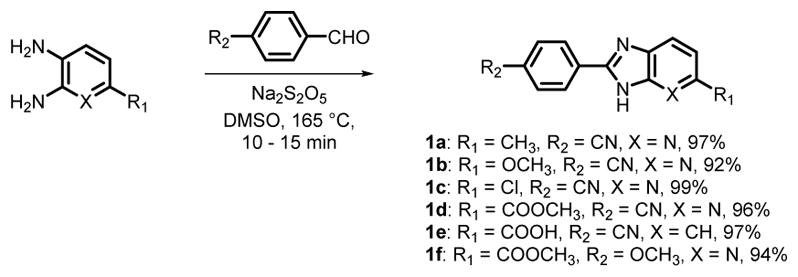

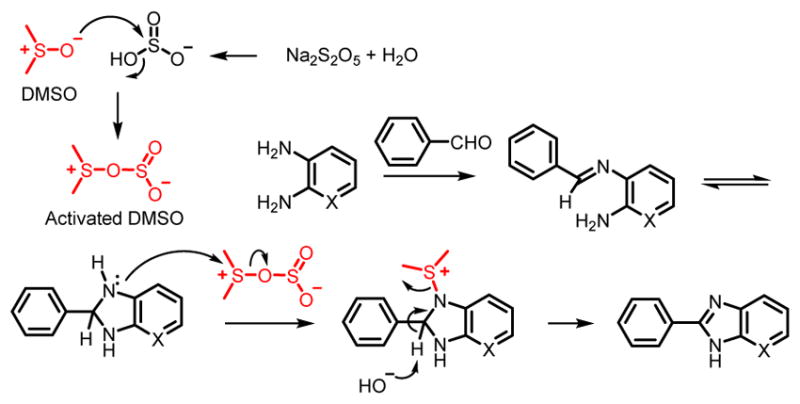

DMSO-Mediated Cyclization

As mentioned above, we desired to optimize reaction conditions for efficient construction of substituted BI/azaBI rings. There are numerous conditions starting from aromatic aldehydes and o-phenylenediamine or 2,3-diaminopyridine to make the BI and azaBI, respectively, through an oxidative cyclization. Indeed, a 2012 review by Panda et al. listed 118 different conditions for this synthesis.39 The first step in this cyclization is the formation of the imine, followed by the cyclic aminal, which is then oxidized to the imidazole ring. We examined the most common conditions to make 1a. Reaction in DMF in presence of Na2S2O5 or Na-HSO340 at 120 or 165 °C took 48 h and produced side products which mandated lengthy purification. A recent method stirring the reactants in hot DMF/H2O (9:1)41 gave incomplete reaction.

We speculated that catalyzing the oxidation would facilitate the cyclization. Using p-benzoquinone as an oxidant,39 scandium triflate42 or ferric chloride43 as recyclable oxidants did not improve reaction time or yield of 1a. Although, DMSO is a known oxidant,44 it does not appear to have been explored in this type of synthesis. Thus, we aimed to investigate the effect of DMSO in comparison to DMF for the synthesis of 1a (entry1, Table 1). Performing the reaction in DMSO under the same conditions, surprisingly, resulted in a complete reaction in only 15 min (entry 2). Most importantly, the product was easily recovered by adding water, and filtering the resulting precipitate, where no further purification was required as indicated by 1H NMR. The cyclization of more derivatives (1b–1f) under the same conditions was finished in 10–15 min, giving excellent yields of 92–99% (Scheme 2).In order to evaluate the role of DMSO, we ran the reaction in the absence of Na2S2O5 and air (entries 3 and 4). The results indicated that both DMSO and Na2S2O5 are crucial. The reactants were freely soluble in both DMF and DMSO; hence the role of DMSO was beyond solvation.45 Thus, we propose the mechanism shown in Scheme 3, suggesting that DMSO reacts with bisulfite to form an activated intermediate that takes part in the oxidation. This hypothesis is supported by related formation of an activated DMSO in the Swern, Moffatt-Pfitzner and Parikh-Doering oxidations of alcohols.44,46

Table 1.

Influence of Solvent on Cyclization of 1a at 165 °C

| entry | solvent | catalyst | atmosphere | time (h) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DMF | Na2S2O5 | air | 48 | 56 |

| 2 | DMSO | Na2S2O5 | air | 1/4 | 97 |

| 3 | DMSO | none | air | 1/4-1 | 0 |

| 4 | DMSO | Na2S2O5 | argon | 1/4 | 97 |

Scheme 2.

Efficient Cyclization of BI and azaBI Rings

Scheme 3.

Plausible Mechanism for DMSO Reaction

Application on More Complex Molecules

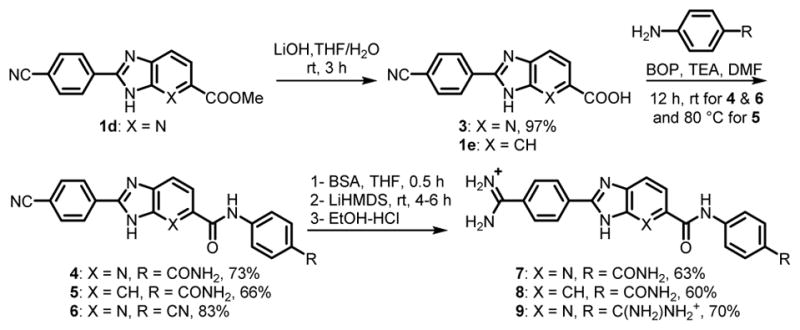

We tested our transient protection strategy for amidine synthesis on more complex BI/azaBI structures of six different amidines, which were designed as minor groove binders for specific recognition of DNA sequences. The synthesis of amide-containing mono- and diamidino derivatives, 7–9 is shown in Scheme 4. 1d was hydrolyzed to give acid 3, which was coupled with both 4-aminobenzamide and 4-aminobenzonitrile to give the azaBI mononitrile derivative containing two amide groups (4), and the dinitrile with one amide (6), respectively. Similarly, 1e was reacted to give the BI mononitrile derivative (5) with one amide group. While transiently protecting 4–6 for the one-pot preparation of amidines 7–9, BSA was also expected to silylate the amide groups.35,47 Hence, a molar ratio of BSA was used to fully silylate all the NH’s. The amidines, 7–9 were obtained in good yields (Scheme 4) and high purity.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Amidino-BI/azaBI carrying Amides

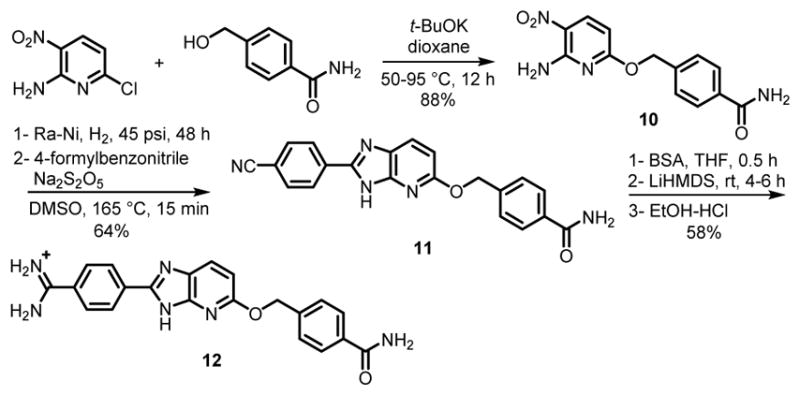

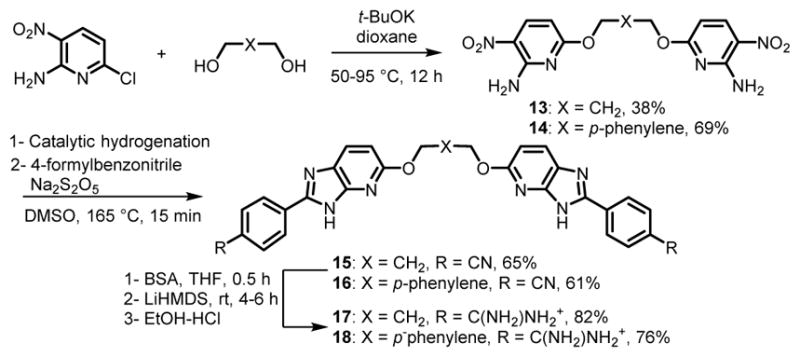

Schemes 5 and 6 represent the preparation of the monoamidine 11, and the symmetric diamidines 17 and 18. 4-(Hydroxymethyl)benzamide48 was coupled with 2-amino-6-chloro-3-nitropyridine in presence of t-BuOK49 to form the nitro derivatives, 10, which was reduced to the diamine and immediately used in the DMSO-mediated cyclization described above to give mononitrile 11 (Scheme 5). The dinitirile intermediates 15 and 16 (Scheme 6) were prepared in a similar fashion. The one-pot amidine synthesis gave 12, 17 and 18 (Schemes 5 and 6). All the nitrile intermediates of Schemes 4–6 were highly soluble upon TMS protection. The cyclization reactions for 11, 15 and 16 were again finished in 15 min, but crystallization was required to afford pure azaBI products in yields of 61–65%.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of Amidino-azaBI Carrying Benzyl Ether and Amide

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Diamidino-azaBI Carrying Ether and Benzyl Ether Linkages

In conclusion, transient protection with TMS using BSA is a convenient and efficient strategy, which allowed the use of LHMDS to make BI and azaBI amidines from nitriles in a one-pot procedure. This strategy is advantageous in two ways: (1) it renders the nitrile intermediates highly soluble in THF leading to shorter reaction times, (2) it results in pure products, avoiding the need for extensive purification. This method is applicable on amide containing nitriles, and is a much needed alternative for the Pinner Reaction. The amidines prepared by our new strategy were obtained in high yields of up to 88%. The transient protection should work in general where active OH/NH protons obstruct the LHMDS reaction35 and the strategy is applicable for a wide range of cases where strong bases are used or increased solubility is needed to enhance the kinetics of a reaction.

The synthesis of the BI and azaBI imidazole rings from the aldehyde and diamine in presence of metabisulfite has been optimized by using DMSO as a solvent. This condition led to significantly shorter reaction time than known conditions, where reactions were finished in only 10–15 min. The products were highly pure in most cases. Activated DMSO oxidation, presumably, plays an essential role in facilitating the imidazole ring formation.

These methods present significant advances, important for the facile synthesis of BI/azaBI derivatives industrially, for new drug synthesis, and for the design of ligands with specific binding and recognition of DNA bases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Moses Lee of Georgia State University for advice on the synthesis of methyl 6-amino-5-nitropicolinate. This work was supported in the United States by the National Institute of Health [GM111749 to W.D.W and D.W.B].

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures, characterization, 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF)

References

- 1.Bansal Y, Silakari O. Biorg Med Chem. 2012;20:6208. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10257. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira RS, Dessoy MA, Pauli I, Souza ML, Krogh R, Sales AIL, Oliva G, Dias LC, Andricopulo AD. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2380. doi: 10.1021/jm401709b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaba M, Singh S, Mohan C. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;76:494. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaPlante SR, Boes M, Brochu C, Chabot C, Coulombe R, Gillard JR, Jakalian A, Poirier M, Rancourt J, Stammers T, Thavonekham B, Beaulieu PL, Kukolj G, Tsantrizos YS. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1845. doi: 10.1021/jm4011862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garuti L, Roberti M, Bottegoni G. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:2284. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140217105714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasbinder MM, Alimzhanov M, Augustin M, Bebernitz G, Bell K, Chuaqui C, Deegan T, Ferguson AD, Goodwin K, Huszar D, Kawatkar A, Kawatkar S, Read J, Shi J, Steinbacher S, Steuber H, Su Q, Toader D, Wang H, Woessner R, Wu A, Ye M, Zinda M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:60. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KM, Lee KS, Lee GY, Jin H, Durrance ES, Park HS, Choi SH, Park KS, Kim YB, Jang HC, Lim S. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;409:1. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumat B, Bordeau G, Faurel-Paul E, Mahuteau-Betzer F, Saettel N, Metge G, Fiorini-Debuisschert C, Charra F, Teulade-Fichou MP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12697. doi: 10.1021/ja404422z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Heo CH, Kim HM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17969. doi: 10.1021/ja409971k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang N, Tian X, Zheng J, Zhang X, Zhu W, Tian Y, Zhu Q, Zhou H. Dyes Pigm. 2016;124:174. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munde M, Wang S, Kumar A, Stephens CE, Farahat AA, Boykin DW, Wilson WD, Poon GMK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Kumar A, Depauw S, Nhili R, David-Cordonnier MH, Lee MP, Ismail MA, Farahat AA, Say M, Chackal-Catoen S, Batista-Parra A, Neidle S, Boykin DW, Wilson WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10171. doi: 10.1021/ja202006u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahimian M, Kumar A, Say M, Bakunov SA, Boykin DW, Tidwell RR, Wilson WD. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1573. doi: 10.1021/bi801944g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairley TA, Tidwell RR, Donkor I, Naiman NA, Ohemeng KA, Lombardy RJ, Bentley JA, Cory M. J Med Chem. 1993;36:1746. doi: 10.1021/jm00064a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harika NK, Paul A, Stroeva E, Chai Y, Boykin DW, Germann MW, Wilson WD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul A, Chai Y, Boykin DW, Wilson WD. Biochemistry. 2015;54:577. doi: 10.1021/bi500989r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chai Y, Paul A, Rettig M, Wilson WD, Boykin DW. J Org Chem. 2014;79:852. doi: 10.1021/jo402599s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darnell JE. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:740. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koehler AN. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:331. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson WD, Tanious FA, Mathis A, Tevis D, Hall JE, Boykin DW. Biochimie. 2008;90:999. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dox AW, Whitmore FC. Acetamidine Hydrochloride. In: Blatt AH, editor. Organic Syntheses. 2. Vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1941. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judkins BD, Allen DG, Cook TA, Evans B, Sardharwala TE. Synth Commun. 1996;26:4351. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thurkauf A, Hutchison A, Peterson J, Cornfield L, Meade R, Huston K, Harris K, Ross PC, Gerber K, Ramabhadran TV. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2251. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalifa MM, Bodner MJ, Berglund JA, Haley MM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:4109. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, DeKorver KA, Lohse AG, Zhang YS, Huang J, Hsung RP. Org Lett. 2009;11:899. doi: 10.1021/ol802844z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlin S, Wang S, Kumar A, Farahat AA, Boykin DW, Wilson WD. Chem - Eur J. 2015;21:5528. doi: 10.1002/chem.201406322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ismail MA, Batista-Parra A, Miao Y, Wilson WD, Wenzler T, Brun R, Boykin DW. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:6718. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger O, Kaniti A, van Ba CT, Vial H, Ward SA, Biagini GA, Bray PG, O’Neill PM. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:2094. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chackal-Catoen S, Miao Y, Wilson WD, Wenzler T, Brun R, Boykin DW. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:7434. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaires JB, Ren J, Hamelberg D, Kumar A, Pandya V, Boykin DW, Wilson WD. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5729. doi: 10.1021/jm049491e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farahat AA, Paliakov E, Kumar A, Barghash AEM, Goda FE, Eisa HM, Wenzler T, Brun R, Liu Y, Wilson WD, Boykin DW. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:2156. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vorbrüggen H, Ruh-Pohlenz C. Organic Reactions. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. Synthesis Of Nucleosides. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ti GS, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1316. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klebe JF, Finkbeiner H, White DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3390. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goker H, Ozden S, Yildiz S, Boykin DW. Eur J Med Chem. 2005;40:1062. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendt MD, Rockway TW, Geyer A, McClellan W, Weitzberg M, Zhao X, Mantei R, Nienaber VL, Stewart K, Klinghofer V, Giranda VL. J Med Chem. 2004;47:303. doi: 10.1021/jm0300072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakunova SM, Bakunov SA, Wenzler T, Barszcz T, Werbovetz KA, Brun R, Tidwell RR. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4657. doi: 10.1021/jm900805v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panda SS, Malik R, Jain SC. Curr Org Chem. 2012;16:1905. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alp M, Goker H, Brun R, Yildiz S. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:2002. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee YS, Cho YH, Lee S, Bin JK, Yang J, Chae G, Cheon CH. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:532. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh T, Nagata K, Ishikawa H, Ohsawa A. Heterocycles. 2004;63:2769. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh MP, Sasmal S, Lu W, Chatterjee MN. Synthesis. 2000:1380. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tidwell TT. Synthesis. 1990:857. [Google Scholar]

- 45.We thank a reviewer for suggesting evaluation of the importance of DMSO’s solvation role in the enhanced cyclization reaction. We tested this using o-phenylenediamine and 4-cyanobenzaldehyde in DMF in the presence of 1.1 and 2.0 equivalents of DMSO, under the same conditions. 70% conversion of the starting material was observed with 1.1 equivalents of DMSO, while 100% conversion was attained using 2.0 equivalents as detected by proton NMR.

- 46.Wu XF, Natte K. Adv Synth Catal. 2016;358:336. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li NS, Piccirilli JA. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8754. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34556k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kita Y, Nishii Y, Onoue A, Mashima K. Adv Synth Catal. 2013;355:3391. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tasker SZ, Bosscher MA, Shandro CA, Lanni EL, Ryu KA, Snapper GS, Utter JM, Ellsworth BA, Anderson CE. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8220. doi: 10.1021/jo3015424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.