Abstract

Tip growth is a focused and tightly regulated apical explosion that depends on the interconnected activities of ions, the cytoskeleton, and the cell wall.

Tip growth is a specialized type of growth utilized by only a few cell types in the plant kingdom. Nevertheless, these cell types perform vital functions for plants. Pollen tubes are necessary for seed plant reproduction, root hairs are vital for nutrient acquisition, and protonemata comprise the entire juvenile moss plant. Tip growth requires exquisite coordination of intracellular cargo delivery and simultaneous weakening of the apical cell wall. This process is precarious, with imbalances resulting in cell rupture or cessation of growth. In this Update, we provide context and highlight recent advances in our understanding of how ions, the cytoskeleton, and properties of the cell wall are interconnected during tip growth across three tip-growing systems: pollen tubes, root hairs, and protonemata. We propose that further mechanistic insights are likely to come from studying the commonalities among these systems, particularly focusing on the molecular basis of the communication between cell wall status and intracellular cargo delivery.

Plant cells are surrounded by a cell wall that imposes both physical restrictions to shape as well as a balance to turgor pressure. However, most undifferentiated plant cells are small and uniform. During differentiation, plant cells expand, which occurs when loosening events allow the wall to yield to the existing turgor pressure, discussed further in this issue (Cosgrove, 2018). The momentary decrease in water potential results in an influx of water, causing expansion. As new cell wall material is deposited to account for this expansion, the increase in size becomes irreversible, and thus the cell has grown. Modifications to cell wall viscosity promoting expansion can result from a number of different processes. For example, cell wall-loosening enzymes may be activated in or delivered to specific regions. Alternatively, the secretion of flexible cell wall material could be spatially regulated.

One extreme form of cell wall patterning is known as tip growth. In tip-growing cells, the zone of reduced cell wall viscosity is focused at the apex of the growing cell. To grow, the cell must balance the delivery of wall material with the retrieval of excess membrane, as the delivery of excess flexible wall material at the cell tip could result in lysis. Tip growth occurs across plant lineages in cell types such as pollen tubes, root hairs, moss protonemata, and bryophyte and algal rhizoids. Although tip growth mechanisms have been generalized as equivalent in pollen tubes, root hairs, and moss protonemata, it is likely that significant differences exist in order for these cells to carry out their divergent functions.

Of the three cell types, pollen tubes are the most specialized and short-lived cell, in that their aim is to deliver the sperm cells to the ovule. By transmitting location information about the ovule from outside the pollen tube to the intracellular growth machinery, pollen tubes grow rapidly toward the female gametophyte and burst upon entry. Root hairs are the site of nutrient and water uptake for the plant. In contrast to pollen tubes, root hairs are longer-lived and must integrate many environmental cues (moisture, nutrient content, soil texture, etc.). Root hairs internalize this suite of information to maximize the efficacy of their growth. In contrast to pollen tubes and root hairs, moss protonemata have a colonization role. They germinate from the spore and race against other plants to acquire moisture, nutrients, and an optimal position for photosynthesis. This tip-growing cell continues to undergo cell divisions as the plant develops, reaching a point in which the entire juvenile plant, persisting on the scale of months, consists entirely of protonemata. Thus, moss protonemata are longer-lived than both pollen tubes and root hairs and integrate substantially more environmental information during their growth and development. Even with such divergent functions, mechanistically describing tip growth in each system promises to illuminate fundamental processes conserved throughout plant evolution as well as derived processes that may have evolved in each cell type.

Ultimately, the key to understanding tip growth will require understanding a complex interaction network; the reader is directed to recent reviews that expand upon a variety of facets of tip growth not covered here (Mendrinna and Persson, 2015; Hepler, 2016; Damineli et al., 2017; Michard et al., 2017; Stephan, 2017). In this Update, we speculate that further mechanistic advances will come from identifying deeply conserved tip growth mechanisms that decipher signaling events between the cell wall and the cytoplasm. Thus, we will focus on advances in the understanding of cytoskeletal organization, intracellular ion gradients, and the cell wall itself, all key aspects involved in tip growth signaling. A link between wall status and cytoplasmic activity is critical because, in many ways, tip growth resembles a controlled explosion: the cell wall must weaken exactly enough to allow for expansion but not so much that the cell ruptures. Indeed, there are many conditions under which this balance is lost, resulting in either growth arrest or tip bursting. We have compiled a list of agents and mutants that uncouple various aspects of tip growth with similar results (Table I). While not an exhaustive list, Table I demonstrates the wide-ranging conditions that disrupt the precarious balancing act between intracellular and extracellular events during tip growth. By identifying the molecular targets of agents and cellular deficiencies in mutants leading to growth arrest or tip blowout, it may be possible to understand the molecular regulation of this controlled explosion (see Outstanding Questions).

Table I. Agents and mutants abrogating tip growth.

RNAi, RNA interference; N/A, not applicable.

| Treatment/Mutant | Cellular Consequence | Gene Name | Growth Consequence | System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latrunculin B | Actin depolymerization | N/A | Swelling, loss of polarized growth | Pollen tubes, root hairs, protonemata | Gibbon et al. (1999); Ketelaar et al. (2003);Harries et al. (2005) |

| Calcium ionophore | Equalizes calcium concentrations | N/A | Apical wall thickening, growth reorientation | Root hairs, pollen tubes | Malho and Trewavas (1996); Monshausen et al. (2008) |

| Oryzalin | Microtubule depolymerization | N/A | Loss of directional growth | Root hairs, moss protonemata | Doonan et al. (1988); Bibikova et al. (1999) |

| Lanthanum | Calcium channel and pump blocker | N/A | Bursting | Pollen tubes, root hairs | Monshausen et al. (2008) |

| Cyanide | ATP synthesis inhibition | N/A | Apical wall thickening | Pollen tubes | Winship et al. (2016) |

| Propidium iodide | Competes with calcium in cell wall | N/A | Bursting | Pollen tubes | Rounds et al. (2011) |

| EGTA/EDTA | Low extracellular calcium | N/A | Bursting | Pollen tubes, root hairs | Monshausen et al. (2008) |

| Acidic growth medium | Low extracellular pH | N/A | Bursting | Root hairs | Monshausen et al. (2008) |

| Yariv agent | Arabinogalactan protein blocking | N/A | Expansion stops, deposition continues | Pollen tubes, moss protonemata | Roy et al. (1999); Lee et al. (2005) |

| apg knockdown/knockout | Aberrant extracellular signaling | ARABINOGALACTAN | Shorter cells | Pollen tubes, moss protonemata | Lee et al. (2005); Levitin et al. (2008) |

| cngc mutants | Aberrant calcium signaling | CYCLIC NUCELOTIDE-GATED CHANNELS | Shorter, deformed cells | Pollen tubes, root hairs | Gao et al. (2016);Zhang et al. (2017) |

| glr1.2 mutant | Aberrant calcium signaling | GLU RECEPTOR-LIKE | Deformed cells | Pollen tubes | Michard et al. (2011) |

| exo70C mutant | Faster growth rate, thin cell wall | EXOCYTOSIS 70C2 | Bursting | Pollen tubes | Synek et al. (2017) |

| cog3 and cog8 single mutants | Aberrant Golgi morphology, vesicle trafficking | CONSERVED OLIGOMERIC GOLGI 3 and 8 | Bursting | Pollen tubes | Tan et al. (2016) |

| anx1,anx2 double mutant | Aberrant cell wall formation | ANXUR 1 and 2 | Bursting | Pollen tubes | Boisson-Dernier et al. (2009) |

| LePRK RNAi/overexpression | Aberrant extracellular signaling | POLLEN RECEPTOR KINASE | Knockdown: shorter pollen tubes, bursting; overexpression: ballooning of tip | Pollen tubes | Gui et al. (2014) |

| lrx1,lrx2 double mutant | Aberrant extracellular signaling | LUCINE-RICH REPEAT EXTENSIN 1 and 2 | Rupture after initiation | Root hairs | Baumberger et al. (2003) |

| prx44 mutant | Aberrant extracellular signaling | PEROXIDASE44 | Bursting | Root hairs | Kwon et al. (2015) |

| kjk/csld3 mutant | Aberrant cell wall formation | KOJAK/cellulose synthase-like D3 | Rupture after initiation | Root hairs | Favery et al. (2001) |

| bup mutant | Loss of germination plaque | BURSTING POLLEN (Golgi-localized glycosyltransferase) | Bursts upon germination | Pollen tubes | Hoedemaekers et al. (2015) |

| ext18 mutant | Aberrant cell wall formation | EXTENSIN18 | Bursting | Pollen tubes | Choudhary et al. (2015) |

| reb1 mutant | Altered sugar metabolism | ROOT EPIDERMAL BULGER1 | Ballooning | Root hairs | Andème-Onzighi et al. (2002) |

| ROP RNAi | Aberrant intracellular signaling | Rho/Rac of Plants (small GTPase) | Loss of polarized growth, loss of cell adhesion | Moss protonemata | Burkart et al. (2015) |

| ROP overexpression | Aberrant intracellular signaling | Rho/Rac of Plants | Swelling, branching | Pollen tubes, root hairs | Wu et al. (2001); Jones et al. (2002) |

THE CYTOSKELETON

Within the cell, both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons contribute to tip growth. As we discuss the structure of these cytoskeletons in tip-growing cells, it is important to recall that each array is decorated with, and regulated by, microtubule- and actin-binding proteins. Thus, their localization (Table II) during tip growth provides insights into the mechanism of cytoskeletal organization and dynamics.

Table II. Localization of cytoskeleton-binding proteins.

MTs, Microtubules; PM, plasma membrane.

| Protein | Localization | Species/System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fimbrin | 1) Apical and subapical F-actin structures | 1) Lily pollen tubes | 1) Su et al. (2012), α-LlFIM1 antibody |

| 2) Apical filaments | 2) Arabidopsis pollen tubes | 2) Zhang et al. (2016), pFIM5::FIM5-GFP | |

| Villin | 1) AtVLN3, thick subapical filaments | 1) Arabidopsis root hairs | 1) van der Honing et al. (2012), pAtVLN3::VLN3-GFP |

| 2) AtVLN2, thick subapical filaments, fine apical filaments | 2 and 3) Arabidopsis pollen tubes | 2) Qu et al. (2013), pAtVLN2::VLN2genomic-GFP | |

| 3) AtVLN5, thick subapical filaments, fine apical filaments | 3) Qu et al. (2013), pAtVLN5::VLN5genomic-GFP | ||

| Actin Depolymerizing Factor (ADF)/Cofilin | 1) Apical and subapical actin structures | 1) Tobacco pollen tubes and grains | 1) Chen et al. (2002), Lat52::NtADF-GFP |

| 2) Apical structures | 2) Lily pollen tubes | 2) Lovy-Wheeler et al. (2006), α-lily ADF antibody | |

| 3) Cytoplasmic | 3) P. patens protonemata | 3) Augustine et al. (2008), α-PpADF polyclonal antibody | |

| Profilin | Cytoplasmic | Lily pollen grains and tubes | Vidali and Hepler (1997), α-profilin polyclonal antibody |

| Actin Interacting Protein1 | 1) Apical F-actin fringe | 1) Lilium spp. pollen tubes | 1) Lovy-Wheeler et al. (2006), α-lily AIP antibody |

| 2) Cytoplasmic | 2) P. patens protonemata | 2) Augustine et al. (2011), AIP-mCherry locus integration | |

| Class I Formin | LlFH1, apical vesicles, PM | Lily pollen tubes | Li et al. (2017), transient overexpression of LlFH1-GFP |

| Class II Formin | PpFor2a, apex, not on PM | P. patens protonemata | Vidali et al. (2009b), For2a 3xGFP locus integration |

| Class VIII Myosin | PpMyo8A, cortical puncta with apical accumulation, spindle and phragmoplast midzone | P. patens protonemata | Wu and Bezanilla (2014), pMaizeUbiquitin::Myo8A-3xGFP, in Δmyo8 a,b,c,d,e |

| Class XI Myosin | 1) PpMyo11a cytosolic with apical enrichment | 1) P. patens protonemata | 1) Vidali et al. (2010), pMaizeUbiquitin::3xGFP-Myo11a |

| 2) AtMyo11k, apical cloud | 2) Arabidopsis root hairs | 2) Park and Nebenführ (2013), pMyo11K::YFP-Myo11K | |

| Kinesin | 1) KIND1a,b, plus ends of MTs focused on the tip | 1) P. patens protonemata | 1) Hiwatashi et al. (2014), KIND1a/1b-cerulean locus integration |

| 2) ARK1, cytoplasmic, plus ends of MTs | 2) Arabidopsis root hairs | 2) Eng and Wasteneys (2014), pARK1::ARK1-GFP | |

| Actin Related Protein2/3 (ARP2/3) complex | PpARPC4, apically enriched cap | P. patens protonemata | Perroud and Quatrano (2006), 2xYFP locus integration |

| Brick1 (brk1) | PpBRK1, apically enriched cap | P. patens protonemata | Perroud and Quatrano (2008), 3xYFP locus integration |

| Rho/Rac of Plants (ROP) | 1) AtROP2, apical dome | 1) Tobacco pollen tubes | 1) Kost et al. (1999), LAT52::GFP-AtROP2 |

| 2) ROP1, apical dome | 2) Arabidopsis root hairs | 2) Jones et al. (2002), 35S::GFP-ROP2 | |

| 3) AtROP1-PM, apical enrichment, cytoplasm | 3) Tobacco pollen tubes | 3) Hwang et al. (2005), LAT52::RIC4ΔC-GFP | |

| 4) PpROP2-PM, enrichment at cross walls | 4 and 5) P. patens protonemata | 4) Ito et al. (2014), HSP::cerulean-PpROP2 | |

| 5) PpROP4, apical PM and cross walls | 5) P. patens protonemata | 5) Burkart et al. (2015), pROP4::GFP-ROP4coding sequence, locus replacement | |

| ROP Activating Proteins (RopGAPs) | NtRopGAP1, subapical PM | Tobacco pollen tubes | Klahre and Kost (2006), Lat52::YFP-NtRopGAP1 |

| ROP Interacting CRIB-Containing Protein (RIC) | 1) AtRIC 3,10, cytosolic | 1 to 4) Tobacco pollen tubes | 1) Wu et al. (2001), Lat52::GFP-RIC n |

| 2) AtRIC 1, 6, 7, apical PM, cytosolic | 2) Wu et al. (2001), Lat52::GFP-RIC n | ||

| 3) AtRIC9, PM | 3) Wu et al. (2001), Lat52::GFP-RIC 9 | ||

| 4) AtRIC 2, 4, 5, apical PM | 4) Wu et al. (2001), Lat52::GFP-RIC n | ||

| ROP Guanine Dissociation Inhibitors (RopGDIs) | NtRopGDI2, cytosolic | Tobacco pollen tubes | Klahre et al. (2006), Lat52::YFP-NtRopGDI2 |

| ROP Guanine Exchange Factors (RopGEFs) | 1) AtRopGEF1, apical PM | 1 to 3) Tobacco pollen tubes | 1) Gu et al. (2006), Lat52::GFP-RopGEF1 |

| 2) AtRopGEF 8, 9, 14, apical PM, cytoplasm | 2) Gu et al. (2006), Lat52::GFP-RopGEF n | ||

| 3) AtRopGEF12, cytoplasm | 3) Gu et al. (2006), Lat52::GFP-RopGEF12 | ||

| 4) PpRopGEF3, cytoplasmic apical enrichment | 4) P. patens protonemata | 4) Ito et al. (2014), HSP::PpRopGEF3-cerulean | |

| Microtubule-Associated Protein18 | 1) Shank PM, inverted cone at tip | 1) Arabidopsis pollen tubes | 1) Zhu et al. (2013), pAtMAP18::AtMAP18-GFP |

| 2) Shank of PM, apical cytoplasm | 2) Arabidopsis root hairs | 2) Kang et al. (2017), pAtMAP18::AtMAP18-mCherry | |

| End-Binding1 | 1) Cortical puncta, apical accumulation | 1) P. patens protonemata | 1) Hiwatashi et al. (2014), PpEB1b-mCitrine locus integration |

| 2) Cytoplasmic puncta | 2) Arabidopsis root hairs | 2) Eng and Wasteneys (2014), 35S::AtEB1b-GFP |

Actin Cytoskeleton

Of the two cytoskeletal elements in plants, the actin cytoskeleton, which is discussed further in this issue (Szymanski and Staiger, 2018), is essential for tip growth in angiosperm pollen tubes, root hairs, and moss protonemata. To understand how actin contributes to cell expansion, it is important to determine the subcellular architecture of the F-actin arrays. However, across these systems, visualizing F-actin has been challenging. For example, in fixed cells, fluorescent phalloidin, a widely used probe for F-actin in many cell types, does not readily stain plant cells (discussed by Olyslaegers and Verbelen, 1998). Furthermore, phalloidin only interacts with a subset of F-actin arrays (Nishida et al., 1987) and stabilizes F-actin (Cooper, 1987). Thus, phalloidin often leads to an increase in bundled F-actin (Vidali et al., 2009a). Additionally, to date, GFP-actin fusions have not been successful in plants. Thus, for live-cell imaging, researchers have used fluorescent actin-binding probes, such as Lifeact (Riedl et al., 2008), talin (Kost et al., 1998), and the actin-binding domain of fimbrin (Sheahan et al., 2004). However, these probes also generate artifacts, particularly when highly expressed (Vidali et al., 2009a; van der Honing et al., 2011).

Many of the issues arising from using F-actin probes stem from the fact that the binding of these probes to F-actin differs and often is affected by proteins that may be associated with the actin cytoskeleton (Table II). Thus, depending on the probe used and the relative amount of the probe, different subcellular structures can be observed. For example, in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) pollen tubes, fluorescent phalloidin staining revealed F-actin occupying the whole tip region, while Lifeact-GFP revealed pollen tubes with relatively little actin at the tip (Zhang et al., 2016). In root hairs, Ketelaar et al. (2003) visualized F-actin with antibodies or phalloidin. While both methods produced similar results in general, the details of the actin structure were quite different. In moss protonemata, F-actin imaging with fluorescent phalloidin (Vidali et al., 2009a) and Talin-GFP (Finka et al., 2007; Perroud and Quatrano, 2008), revealed thick apical bundles and a prominent apical accumulation. However, the expression of Lifeact-GFP at noninhibitory levels labeled finer actin filaments and provided more detail in the apical structures (Vidali et al., 2009a). Given the species-specific variation and the inherent challenges of imaging F-actin arrays, one must consider the conclusions made within the context of the visualization method and plant species used.

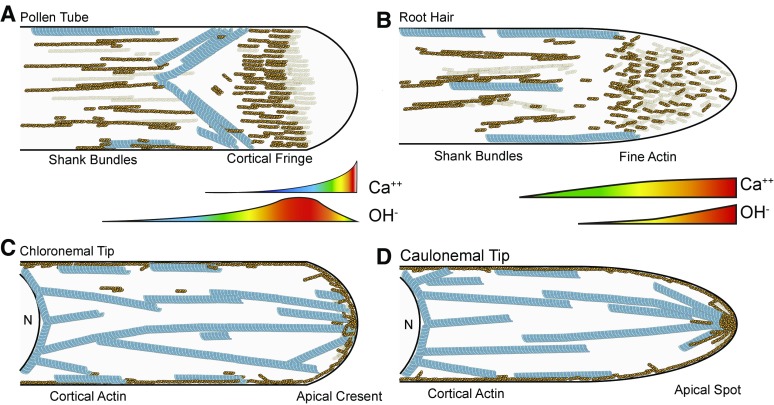

Despite differences in F-actin structures between the probes used and the species of cell type examined (Stephan, 2017), it is nevertheless possible to recognize an emergence of commonalities. For example, most pollen tubes exhibit a fringe of short longitudinally oriented actin microfilaments located at the cell cortex near the cell tip, and long actin bundles are found along the length of the cell (Lovy-Wheeler et al., 2005; Fig. 1A). In growing pollen tubes expressing Lifeact-GFP, the fringe was observed to rapidly remodel and move forward with growth (Rounds et al., 2014). Additionally, when pollen tube growth was inhibited with cyanide, the apical fringe degraded more rapidly than the actin cables in the shank of the tube (Winship et al., 2016). In pollen grains, Vogler et al. (2015) showed an F-actin accumulation 180° from the future germination site. This accumulation translocates to the shank after growth initiates. Using a pollen-specific promoter, Actin3, to drive the expression of Lifeact-GFP, Jásik et al. (2016) reported fine F-actin at the tip and dynamic actin along the shank of germinating pollen tubes. Studies such as these demonstrate that pollen tubes have at least two distinct arrays: an apical array that is very dynamic and a subapical array that tends to have more bundled F-actin.

Figure 1.

Apical cytoskeletal structures and ion gradients. A, Pollen tube, modeled after lily. Cortical F-actin (orange) forms a fringe overlapping with the OH− gradient and the outer reaches of the calcium gradient. Microtubules (blue) form an inverted cone that just intersects the actin fringe. B, Root hair, modeled after Arabidopsis. Short F-actin filaments fill the apex, overlapping with the highest levels of calcium and OH−. As both gradients taper off, actin bundles and microtubules are found toward the rear of the cell. C, Moss chloronemal tip, modeled after P. patens. Apical actin is enriched along the entire dome, and fine cortical actin is present along the length of the cell. Contiguous cytoplasmic microtubules originating from the nucleus (N) point toward the cell tip. D, Moss caulonemal tip, modeled after P. patens. The apical actin is a highly focused spot and also the target of polymerizing cytoplasmic microtubules.

F-actin structures in growing root hairs share aspects of pollen tube structures. Actin bundles are prominent along the shank of the root hair but do not invade the tip region (Fig. 1B). Rather than a fringe, fine actin filaments appear at the tip (Ketelaar, 2013). As with the apical actin structures in pollen tubes, the fine actin filaments in the apex of root hairs are dynamic, as they are more sensitive to depolymerizing drugs than actin cables in the shank (Ketelaar et al., 2003). In addition to vesicle guidance to the tip, it is thought that this fine F-actin functions to keep larger organelles out of the tip region (Emons and Ketelaar, 2009), thus maintaining the apical clear zone (Ketelaar, 2013). Using F-actin as a filter is reminiscent of what has been observed in pollen tubes (Hepler and Winship, 2015).

Moss protonemata have two tip-growing cell types: chloronemata and caulonemata. Chloronemata are distinguished from caulonemata by growing more slowly and possessing perpendicular cell plates. Because caulonemata grow more quickly than chloronemata, F-actin architecture in living tip-growing cells has been analyzed predominantly in caulonemata. Moss protonemata exhibit an enrichment of F-actin at the very apex and fine cortical actin filaments along the length of the cell (Vidali et al., 2009a; Fig. 1, C and D). Bundles are apparent but are few and reside toward the rear of the cell, with subapical cells exhibiting more bundled F-actin. While an apical F-actin enrichment occurs in both cell types, their structures differ depending on the cell type. In chloronemata, apical F-actin localizes over the whole apical dome (Vidali et al., 2009a; Fig. 1C), whereas in caulonemata, F-actin exists as a focused apical spot (Vidali et al., 2010; Fig. 1D). Both the apical F-actin aggregation and the fine cortical F-actin are very dynamic, remodeling on the order of seconds (Vidali et al., 2010). Similar to the apical actin in root hairs, these structures in moss have been shown to be involved in vesicle guidance (Bibeau et al., 2017).

In summary, all three tip-growing cells possess longitudinally oriented actin cables in their shanks. However, apical actin structures differ. Pollen tubes, at least in lily (Lilium longiflorum) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), possess a cortical actin fringe, while moss caulonemata maintain a focused spot of F-actin. Root hairs, in contrast, have an array of fine actin at their tips. Importantly, though, all three tip structures are dynamic, which contrasts with the relatively stable F-actin in the subapical regions. Critically, it is the dynamic apical populations that are essential for tip growth (Vidali et al., 2001; Vazquez et al., 2014).

Microtubule Cytoskeleton

In contrast to the essential nature of F-actin, microtubule-depolymerizing drugs have little effect on angiosperm pollen tube germination and growth in vitro, suggesting that microtubules are not required. However, in both root hairs (Bibikova et al., 1999) and protonemata (Doonan et al., 1988), microtubules likely play a role in maintaining the orientation of polarity. When treated with microtubule-depolymerizing drugs, both cell types no longer grow straight. Instead, the cells tend to change direction and fork, generating two or more outgrowths (Doonan et al., 1988; Bibikova et al., 1999; Ketelaar et al., 2003; Sieberer et al., 2005; Finka et al., 2007).

Regardless of their contribution to tip growth, striking microtubule arrays are evident in pollen tubes as well as root hairs and moss protonemata (Fig. 1). As opposed to F-actin visualization, which relies on actin-binding reagents, imaging the microtubule cytoskeleton is most commonly accomplished by labeling microtubules directly using antibodies to tubulin in fixed material or translational fusions of tubulin with a fluorescent protein in live material. As a result, microtubule imaging is less prone to the artifacts that plague F-actin visualization.

In pollen tubes, microtubules are oriented parallel to the long axis of the cell. In both lily and tobacco pollen tubes, these long cortical microtubules are often coaligned with fine filaments, which appear to be F-actin based on immunogold labeling (Lancelle and Hepler, 1991). Additionally, lily pollen tubes possess a funnel array of microtubules at the interface between the apical clear zone and the shank (Lovy-Wheeler et al., 2005; Fig. 1A). In root hairs, microtubule organization depends on the stage of growth. Generally, root hairs have two populations of microtubules: cortical and endoplasmic (cytoplasmic). Cortical microtubules are observed in both elongating and mature root hairs (Fig. 1B). Whether cortical microtubules are visualized at the very apex is dependent on the method of fixation (Sieberer et al., 2005). The polarity of polymerizing cortical microtubules, however, is dependent on growth status. Growing root hairs have cortical microtubules that grow away from the nucleus and, thus, have baseward and tipward trajectories. Conversely, mature root hairs have exclusive tipward polymerization (Ambrose and Wasteneys, 2014). Similarly, endoplasmic microtubules are only observed in growing root hairs (Sieberer et al., 2005) and emanate from the nucleus (Van Bruaene et al., 2004; Fig. 1B). In moss protonemata, there are also two populations of microtubules: cytoplasmic and cortical. In the apical cell, the polarity of cytoplasmic microtubules between the nucleus and the cell apex is tipward, with an apical focus of microtubule plus ends (Hiwatashi et al., 2014). In contrast, the cortical microtubule array consists of shorter microtubules that lack polarity (Burkart et al., 2015; Nakaoka et al., 2015).

Because microtubules appear to be required for directionality in root hairs and protonemata, one plausible hypothesis is that they spatially restrict specific F-actin populations mediating outgrowth (see Outstanding Questions). In support of this hypothesis,Hiwatashi et al. (2014) discovered that two microtubule-based motors, KINESIN FOR INTERDIGITATED MICROTUBULES1a (KIND1a) and KIND1b, regulate microtubule organization and protonemal growth. The kind1a,b knockout plants exhibit protonemata that do not grow straight but still have tipward-growing cytoplasmic microtubules. However, the apical microtubules are disorganized, suggesting that KIND1a and KIND1b focus apical microtubules in protonemata (Hiwatashi et al., 2014). Interestingly, in wild-type cells, cytoplasmic microtubules focus on the same location occupied by the apical actin spot (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that microtubules may interact directly with the apical F-actin structure. Myosin VIII is an actin-based motor protein that links microtubules to actin during cell division in protonemata (Wu and Bezanilla, 2014; Table II). Protonemata completely lacking myosin VIII (ΔmyoVIIIa,b,c,d,e) grow slowly and less straight than the wild type, particularly when grown under nutrient-deficient conditions (Wu and Bezanilla, 2014). Together, these studies suggest that an active link between actin and microtubules is critical for directionality during tip growth.

Studies of MICROTUBULE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN18 (AtMAP18) also support a role for microtubule-actin interactions in tip growth. MAP18 binds both microtubules and F-actin (Wang et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2013). In addition, MAP18 has calcium-dependent F-actin-severing activity (Zhu et al., 2013). Importantly, MAP18 knockdown pollen tubes cannot grow straight (Zhu et al., 2013), reminiscent of root hairs and protonemata treated with oryzalin (Doonan et al., 1988; Bibikova et al., 1999). Furthermore, F-actin arrays are altered in map18 pollen tubes: map18 pollen tubes no longer exhibit fine apical F-actin; instead, F-actin bundles invade the tip. AtMAP18-GFP localized to the plasma membrane and to an apical inverted cone pattern in map18 knockdown pollen tubes (Zhu et al., 2013; Table II). It is plausible that the location of MAP18 is determined by microtubules, and where microtubules interact with F-actin, the latter may be severed depending on the presence of calcium (Fig. 1).

Interestingly, MAP18 localizes similarly in root hairs (Table II), and MAP18 knockdown plants have root hairs half the length of wild-type plants (Kang et al., 2017). To investigate MAP18’s function in root hairs, Kang et al. (2017) tested for genetic and physical interactions between MAP18 and Rho/Rac of Plants2 (ROP2), a small GTPase considered to be a master regulator of tip growth in root hairs (Jones et al., 2002). Kang et al. (2017) found that MAP18 and ROP2 are in the same genetic pathway and that they interact physically with MAP18, preferentially binding the inactive form of ROP2 and thereby promoting ROP2 activity. Kang et al. (2017) went on to show that MAP18 competes with the ROP2 guanine dissociation inhibitor for binding to ROP2. From these and earlier studies (Wang et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2013), Kang et al. (2017) suggest that MAP18 functions through ROP2 to reinforce polarity and independently of ROP2 by modulating the cytoskeleton.

IONS

Modulation of the many processes and structures involved in tip growth, including the cytoskeleton, is achieved not only by regulator proteins but also by the cytoplasmic environment. Here, we highlight local ion concentrations, in particular calcium and protons, as drivers for these processes (Hepler, 2005, 2016; Michard et al., 2017). To that end, a tip-focused calcium gradient is particularly prominent in growing pollen tubes, where the high point localizes to the extreme apex of the pollen tube, directly appressed to the apical plasma membrane (Fig. 1A). Root hairs have a similarly tip-focused, albeit shallower, calcium gradient (Fig. 1B). To date, calcium in moss protonemata remains understudied. In an early report on dark-grown caulonemata injected with a calcium-sensitive fluorescent dye, Tucker et al. (2005) observed UV (340 and 380 nm light)-stimulated waves associated with both the apex and the base of apical cells. However, Tucker et al. (2005) did not observe a tip-focused calcium gradient, as seen in growing pollen tubes and root hairs.

In root hairs and pollen tubes, many channels both on the plasma membrane as well as on organelles are likely to be involved in establishing and maintaining the apical calcium gradient. Patch-clamp assays have identified stretch-activated channels in pollen tubes (Dutta and Robinson, 2004), and their involvement in generating the apical calcium gradient seems plausible as a product of turgor-driven deformation of the apical plasma membrane. More recently, the Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channel18 (CNGC18) in Arabidopsis was implicated in tip growth, since CNGC18-null plants are male sterile (Gao et al., 2016; Table I). Investigating further, cngc18 pollen tubes were shown to have irregular calcium oscillations and have difficulty finding the ovule. Additionally, root hairs of CNGC14 knockdown and knockout plants are shorter and have altered calcium oscillation profiles (Zhang et al., 2017). Another class of transporters, the Glu receptor family (GLR), plays a role in modulating the calcium signal in pollen tubes. Atglr1.2-1 pollen tubes are deformed, and the amplitudes of calcium oscillations are diminished compared with the wild type (Michard et al., 2011; Table I). In addition to stretch-activated, CNG, and GLR channels, pharmacological assays on pollen suggest that F-actin (Wang et al., 2004) and voltage-regulated (Wu et al., 2011) calcium channels play a role in calcium homeostasis. Further study is needed to determine what complement of channels is required to establish the calcium gradients during tip growth (see Outstanding Questions).

The calcium gradient may modulate growth by stimulating secretion (Winship et al., 2016) and/or regulating F-actin structures through actin-binding proteins, which we focus on here. Two well-established actin-binding proteins with calcium dependence are villin/gelsolin and profilin (Table II), which are prime candidates for playing a key role in establishing different actin arrays in root hairs and pollen tubes. While the actin-binding and bundling activities of both the gelsolin repeat domains and the C-terminal headpiece domain (Finidori et al., 1992) are calcium independent (Khurana et al., 2010), villin’s actin-severing activity is calcium dependent (Huang et al., 2004). Villin’s localization is primarily cytosolic, but it appears to bind to filaments along the shank of root hairs (van der Honing et al., 2012; Table II). It seems likely that apical villin would likely sever, not bundle, F-actin, given the tip-focused calcium gradient (Monshausen et al., 2008). In support of this, vln2vln5 pollen tubes have an enlarged apical actin structure (Qu et al., 2013). Taken together, villin is thought to be a major regulator of actin structures (Huang et al., 2015).

Profilin binds to monomeric actin in a calcium-dependent manner (Kovar et al., 2000) and inhibits nucleation and polymerization. Pollen tubes of profilin mutants have aberrant (Qu et al., 2017) or absent (Liu et al., 2015) actin fringes. Transient knockdown of profilin with RNAi in moss demonstrated that protonemal growth is dependent on profilin (Vidali et al., 2007). Indeed, profilin knockdown plants are significantly less than half the size of controls, and cells grow isotropically (Vidali et al., 2007). The profilin-actin dimer is the substrate for formins: actin nucleators and elongators (Goode and Eck, 2007; Table II). Formins, which are not known to have calcium dependency, will nevertheless be affected by calcium concentrations because they require profilin-actin as a substrate. One can imagine, then, that profilin’s binding activity modulates the structure of the actin array via its interactions with various cellular nucleators of actin polymerization (Suarez et al., 2015).

Pollen tubes and root hairs also possess proton or pH gradients. In growing lily pollen tubes, there is an alkaline band a few micrometers behind the tip, with a small acidic patch at the tip itself (Feijó et al., 1999; Lovy-Wheeler et al., 2006). It is noteworthy that tobacco H+-ATPase1-GFP, an enzyme responsible for creating proton gradients, localizes to the plasma membrane of the shank and an apical cytoplasmic inverted cone in tobacco pollen tubes (Certal et al., 2008), fitting well with the proton gradient (Fig. 1). Although pH gradients are difficult to image because of the rapid diffusion of protons, their importance to tip growth is apparent because modulating intracellular pH can change the direction of growth (Hu et al., 2017). Imaging both the cytosolic and extracellular environments of root hairs also has revealed localized gradients (Monshausen et al., 2007). While the pH gradient is not as steep as in pollen tubes, the gradient is present nonetheless and is coupled with root hair development (Bibikova et al., 1998).

The calcium and pH gradients present at the cell apex of pollen tubes and root hairs are not static but oscillate. Indeed, analyses of these oscillations explore how ion gradients mechanistically link to tip growth. Initial studies on pollen tubes demonstrated that calcium gradient oscillations followed the oscillations in growth rate (Messerli et al., 2000; Cárdenas et al., 2008). By contrast, the apical alkaline band oscillation preceded the growth rate oscillation, virtually matching the oscillation in secretion of new wall material (Lovy-Wheeler et al., 2006). Conversely, studies on the extracellular pH in root hairs indicate that an elevation in alkalinity follows the peak in growth rate (Monshausen et al., 2007). While it is unclear how these studies fit together, the work on pollen tubes provides support for the idea that changes in pH have a close relationship with the process of growth. To explore the connection between calcium, pH gradients, and growth in pollen tubes, Winship et al. (2016) reversibly inhibited pollen tube growth with cyanide (Table I) and then followed the return of the calcium and pH gradients. Although the calcium gradient appeared before growth restarted, it was noticeably behind that of the alkaline band and the process of secretion itself. Indeed, the alkaline band reemerged even before the cyanide had been removed (Winship et al., 2016). These results provide impetus to the notion that pH changes are fundamentally involved in tip growth.

Again, pH regulation of tip growth is thought to affect the actin cytoskeleton. In particular, the elevated pH (7.4), as found in the alkaline band, would stimulate the turnover of F-actin in the fringe in pollen tubes because Actin Depolymerizing Factor (ADF) optimally fragments F-actin at this pH (Bamburg, 1999; Hepler, 2016; Table II). It is additionally noteworthy that, in lily pollen tubes, ADF localizes to the region of the alkaline band and to the actin fringe (Lovy-Wheeler et al., 2006). Activation of ADF activity helps explain the constant turnover of the actin fringe as it keeps pace with elongation. Interestingly, recent work has uncovered a new calcium-ADF interaction. ADF1 from Malus domestica binds to and severs actin in a calcium-dependent manner (Yang et al., 2017), suggesting that dual regulation of ADF may be important for fine-tuning actin fringe turnover. In contrast to pollen tubes, ADF in moss protonemata is cytosolic (Augustine et al., 2008; Table II). However, ADF is absolutely essential for tip growth and F-actin dynamics in protonemata (Augustine et al., 2011), reinforcing the key role that dynamic actin plays in tip growth.

While calcium oscillations in pollen tubes appear to have a single periodicity, quantification of calcium oscillations via light sheet microscopy and spectral analyses in root hairs revealed two concurrent periodicities (Candeo et al., 2017). The mechanism behind the concurrent periodicities in root hairs is not known (see Outstanding Questions). Two methods to generate different periodicities could include variable entry or variable sequestration. For entry, CNGC14 is a prime candidate for being one component of that oscillation profile, as cngc14 root hairs have altered oscillation profiles (Zhang et al., 2017). Mechanisms of sequestration are not as well understood. That being said, pollen tubes with suppressed expression of calreticulin, a resident endoplasmic reticulum protein with calcium sequestration properties, had aberrant cytosolic calcium levels (Suwińska et al., 2017), suggesting a role for calreticulin in calcium homeostasis. How calcium enters the endoplasmic reticulum of pollen tubes, however, is unclear. These works highlight the need to study the mechanism of calcium recycling in tip-growing systems (see Outstanding Questions).

CELL WALL

Plant cell shape, and thus growth, are both confined and defined by the cell wall. To understand how to change the cell wall, for example achieving a local wall weakening at the cell tip for tip growth, one must consider its composition. Tip-growing cells have polymers found in most plant cells, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectins. However, immunochemical data show that the amounts and distribution of these polymers differ from typical plant cells, with cellulose being sparse, while pectin is considerably enriched at the tip in pollen tubes, root hairs, and protonemata (Bosch and Hepler, 2005; Berry et al., 2016). For pollen tubes, mounting evidence increasingly supports the view that pectins, either as deposited directly or following enzymatic modification, play a major role in controlling the rigidity of the wall (Caffall and Mohnen, 2009).

In lily and tobacco pollen tubes, pectins are secreted in an oscillatory manner, with the increase of pectin anticipating the increase in growth rate (McKenna et al., 2009; Rounds et al., 2011). These observations have given rise to the idea that the intercalation or intussusception of wall material weakens the existing wall and allows for stress relaxation at the locus of secretion (Hepler et al., 2013). But further results in tobacco show that pectin methyl esterase (PME) is secreted with the same kinetics as the bulk pectin (McKenna et al., 2009). Thus, PME secretion anticipates growth. It is thought that PME increases the presence of free carboxyl residues, thereby enhancing calcium cross-linking and rigidifying the apical wall (Bosch and Hepler, 2005). This activity can explain the rigidity of the pollen tube shank cell wall. However, at the tube tip, a PME-induced stiffening would be contrary to the local weakening of the wall. An explanation for this paradox may come from work in nonpollen tube systems, where PME may weaken the existing cell wall (Peaucelle et al., 2011, 2012, 2015; Braidwood et al., 2014). The proposed model suggests that PME demethoxylates pectin, rendering the wall components more accessible to degrading enzymes, which, in turn, weakens the wall. Additionally, if PME removes methoxy esters in a block-wise manner, the resulting wall would be more tightly cross-linked by calcium. However, if the PME activity results in random demethoxylation, then the wall would not necessarily be strongly cross-linked. Regardless of the manner of demethoxylation, enzymatic cleavage results in the release of a proton, which locally acidifies the wall and contributes to cell wall loosening and extension. It is also possible that there could be a parallel increase in the PME inhibitor (Röckel et al., 2008), which could negate the esterase activity. Whether PME is active or inactive at the very apex is still unclear. Nevertheless, it is clear that the presence of PME correlates with local weakening, leading to apical cell wall extension.

Glycoproteins also may contribute substantially to cell wall integrity and, thus, polarized growth. Extensin18 (EXT18), a Hyp-rich glycoprotein, appears to direct pollen tube structure and growth (Choudhary et al., 2015). EXT18-null mutants are less fertile, which may result in part from reduced pollen tube growth but also from an increase in pollen tube bursting (Table I). The bursting phenotype lends support to the idea that EXT18 provides structural support to the growing pollen tube at the tip or is involved in the communication between the wall and the cytoplasm.

More attention has been given to arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), which have been shown to modulate growth in different tip-growing cells (Tan et al., 2012). AGPs consist of branched chain carbohydrates linked to a peptide backbone, which may be attached to the plasma membrane through a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol anchor. While ubiquitous, seemingly involved in growth across plant cell types, their specific functions are poorly understood (Ellis et al., 2010). To elucidate the functions of AGPs, many studies have used Yariv phenylglycoside, a dye that binds and stains AGPs as well as blocks their function. At low concentrations (1 μm), Yariv reagent blocks cell extension in pollen tubes (Roy et al., 1998, 1999; Mollet et al., 2002) and moss protonemata (Lee et al., 2005; Table I). Interestingly, the Yariv reagent inhibits cell extension in pollen tubes but not secretion. An electron microscopic analysis revealed that Yariv-treated cells build up wall material in the apical periplasmic space (Roy et al., 1999). In contrast to other inhibitors such as caffeine or cyanide, which degrade the apical calcium gradient, pollen tubes treated with Yariv have only mildly diminished calcium levels at their tip (Roy et al., 1999; Table I). Continued secretion and the presence of the calcium gradient suggest that these activities are likely linked.

Genetic approaches also have implicated AGPs in tip growth. In Arabidopsis, RNAi of AGP6 and AGP11 resulted in plants with reduced fertility, which is partly due to impaired pollen tube growth (Levitin et al., 2008; Table I). Similarly, moss protonemata AGP1 knockout plants have reduced protonemal cell length (Table I). In root hairs, AGPs are reduced markedly in the Arabidopsis reb1-1 mutant. The root epidermal trichoblasts of reb1-1 exhibit morphological defects, including bulging and disorganized cortical microtubules (Andème-Onzighi et al., 2002; Driouich and Baskin, 2008; Table I). Given that REB1 is part of a gene family involved in sugar metabolism, it seems likely that REB1 is involved in the synthesis of AGPs rather than regulating microtubule organization directly. However, compromised AGPs at the plasma membrane and in the cell wall may affect the organization of cortical microtubules (Andème-Onzighi et al., 2002), ultimately affecting the direction of cell expansion (Ketelaar et al., 2003).

While it is clear that AGPs are a major player in cell wall expansion, the underlying mechanism is less straightforward. AGPs could control the assembly or incorporation of new material into the matrix of the cell wall. Alternatively, given that AGPs bind calcium with high affinity, periplasmic AGPs could serve as a calcium capacitor, creating a significant calcium reservoir (Lamport and Várnai, 2013; Lamport et al., 2014). Given that calcium ions are essential for cell wall integrity, it is not clear how the AGP/calcium capacitor modulates the wall. Perhaps the capacitor competes for calcium throughout the wall and works together with the stressed pectin residues to weaken the wall (Boyer, 2009). Alternatively, AGPs might directly facilitate the intercalation of new pectin monomers deep into the wall matrix, where its bonding activities will weaken existing wall bonds (Ray, 1992; Hepler et al., 2013). If the AGP calcium reservoir also is available for intracellular signaling, then it may serve to link wall status to the cytoplasm.

CONCLUSION

In this Update, we have called attention to advances in our understanding of tip growth in pollen tubes, root hairs, and moss protonemata. To establish a mechanistic understanding of tip growth is to elucidate how intracellular events cause a local weakening of the apical cell wall, a prerequisite for turgor-driven cell expansion. The weakening, of course, must be balanced with the deposition of new wall material, or else tip growth fails (Table I). As discussed, localized ion gradients almost certainly play pivotal roles in different processes. For example, the turnover of F-actin in the apex, thought to occur through the ion-dependent activities of actin-binding proteins (Table II), might facilitate the dynamics of exocytic and endocytic vesicles (Bibeau et al., 2017; see Outstanding Questions). It is unsurprising, then, that dynamic ion gradients and cytoskeletal elements occur in the same place: the site of polarized expansion (Fig. 1). Moving forward, it is imperative to understand how the cell wall signals to the intracellular machinery responsible for its expansion (see Outstanding Questions). By continuing to investigate both the similarities and differences across tip-growing systems, we gain deep insights into fundamental and derived processes that sum together in a tip-growing plant cell.

Footnotes

M.B. is supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB-1330171) and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation. C.S.B. received support from the Plant Biology Graduate Program at the University of Massachusetts.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Ambrose C, Wasteneys GO (2014) Microtubule initiation from the nuclear surface controls cortical microtubule growth polarity and orientation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 55: 1636–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andème-Onzighi C, Sivaguru M, Judy-March J, Baskin TI, Driouich A (2002) The reb1-1 mutation of Arabidopsis alters the morphology of trichoblasts, the expression of arabinogalactan-proteins and the organization of cortical microtubules. Planta 215: 949–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine RC, Pattavina KA, Tüzel E, Vidali L, Bezanilla M (2011) Actin interacting protein1 and actin depolymerizing factor drive rapid actin dynamics in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 23: 3696–3710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine RC, Vidali L, Kleinman KP, Bezanilla M (2008) Actin depolymerizing factor is essential for viability in plants, and its phosphoregulation is important for tip growth. Plant J 54: 863–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburg JR. (1999) Proteins of the ADF/cofilin family: essential regulators of actin dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 15: 185–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N, Steiner M, Ryser U, Keller B, Ringli C (2003) Synergistic interaction of the two paralogous Arabidopsis genes LRX1 and LRX2 in cell wall formation during root hair development. Plant J 35: 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry EA, Tran ML, Dimos CS, Budziszek MJ Jr, Scavuzzo-Duggan TR, Roberts AW (2016) Immuno and affinity cytochemical analysis of cell wall composition in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Front Plant Sci 7: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibeau JP, Kingsley JL, Furt F, Tüzel E, Vidali L (2018) F-actin meditated focusing of vesicles at the cell tip is essential for polarized growth. Plant Physiol 176: 352–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova TN, Blancaflor EB, Gilroy S (1999) Microtubules regulate tip growth and orientation in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 17: 657–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibikova TN, Jacob T, Dahse I, Gilroy S (1998) Localized changes in apoplastic and cytoplasmic pH are associated with root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 125: 2925–2934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A, Roy S, Kritsas K, Grobei MA, Jaciubek M, Schroeder JI, Grossniklaus U (2009) Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development 136: 3279–3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Hepler PK (2005) Pectin methylesterases and pectin dynamics in pollen tubes. Plant Cell 17: 3219–3226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JS. (2009) Cell wall biosynthesis and the molecular mechanism of plant enlargement. Funct Plant Biol 36: 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braidwood L, Breuer C, Sugimoto K (2014) My body is a cage: mechanisms and modulation of plant cell growth. New Phytol 201: 388–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart GM, Baskin TI, Bezanilla M (2015) A family of ROP proteins that suppresses actin dynamics, and is essential for polarized growth and cell adhesion. J Cell Sci 128: 2553–2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffall KH, Mohnen D (2009) The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydr Res 344: 1879–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candeo A, Doccula FG, Valentini G, Bassi A, Costa A (2017) Light sheet fluorescence microscopy quantifies calcium oscillations in root hairs of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 58: 1161–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L, Lovy-Wheeler A, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (2008) Pollen tube growth oscillations and intracellular calcium levels are reversibly modulated by actin polymerization. Plant Physiol 146: 1611–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certal AC, Almeida RB, Carvalho LM, Wong E, Moreno N, Michard E, Carneiro J, Rodriguéz-Léon J, Wu HM, Cheung AY, et al. (2008) Exclusion of a proton ATPase from the apical membrane is associated with cell polarity and tip growth in Nicotiana tabacum pollen tubes. Plant Cell 20: 614–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Wong EI, Vidali L, Estavillo A, Hepler PK, Wu HM, Cheung AY (2002) The regulation of actin organization by actin-depolymerizing factor in elongating pollen tubes. Plant Cell 14: 2175–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary P, Saha P, Ray T, Tang Y, Yang D, Cannon MC (2015) EXTENSIN18 is required for full male fertility as well as normal vegetative growth in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 6: 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. (2018) Diffuse growth of plant cell walls. Plant Physiol 176: 16–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA. (1987) Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J Cell Biol 105: 1473–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damineli DSC, Portes MT, Feijó JA (2017) One thousand and one oscillators at the pollen tube tip: the quest for a central pacemaker revisited. In Obermeyer G, Feijo J, eds, Pollen Tip Growth. Springer International Publishing, New York, NY, pp 391–413 [Google Scholar]

- Doonan JH, Cove DJ, Lloyed CW (1988) Microtubules and microfilaments in tip growth: evidence that microtubules impose polarity on protonemal growth in Physcomitrella patens. J Cell Sci 89: 533–540 [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A, Baskin TI (2008) Intercourse between cell wall and cytoplasm exemplified by arabinogalactan proteins and cortical microtubules. Am J Bot 95: 1491–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, Robinson KR (2004) Identification and characterization of stretch-activated ion channels in pollen protoplasts. Plant Physiol 135: 1398–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M, Egelund J, Schultz CJ, Bacic A (2010) Arabinogalactan-proteins: key regulators at the cell surface? Plant Physiol 153: 403–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons AMC, Ketelaar T (2009) Intracellular organization: a prerequisite for root hair elongation and cell wall deposition. In Emons AMC, Ketelaar T, eds, Root Hairs. Springer, Berlin, pp 27–44 [Google Scholar]

- Eng RC, Wasteneys GO (2014) The microtubule plus-end tracking protein ARMADILLO-REPEAT KINESIN1 promotes microtubule catastrophe in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 3372–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favery B, Ryan E, Foreman J, Linstead P, Boudonck K, Steer M, Shaw P, Dolan L (2001) KOJAK encodes a cellulose synthase-like protein required for root hair cell morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 79–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijó JA, Sainhas J, Hackett GR, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (1999) Growing pollen tubes possess a constitutive alkaline band in the clear zone and a growth-dependent acidic tip. J Cell Biol 144: 483–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finidori J, Friederich E, Kwiatkowski DJ, Louvard D (1992) In vivo analysis of functional domains from villin and gelsolin. J Cell Biol 116: 1145–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finka A, Schaefer DG, Saidi Y, Goloubinoff P, Zrÿd JP (2007) In vivo visualization of F-actin structures during the development of the moss Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol 174: 63–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao QF, Gu LL, Wang HQ, Fei CF, Fang X, Hussain J, Sun SJ, Dong JY, Liu H, Wang YF (2016) Cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 18 is an essential Ca2+ channel in pollen tube tips for pollen tube guidance to ovules in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 3096–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon BC, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ (1999) Latrunculin B has different effects on pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell 11: 2349–2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode BL, Eck MJ (2007) Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 593–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Li S, Lord EM, Yang Z (2006) Members of a novel class of Arabidopsis Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors control Rho GTPase-dependent polar growth. Plant Cell 18: 366–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui CP, Dong X, Liu HK, Huang WJ, Zhang D, Wang SJ, Barberini ML, Gao XY, Muschietti J, McCormick S, et al. (2014) Overexpression of the tomato pollen receptor kinase LePRK1 rewires pollen tube growth to a blebbing mode. Plant Cell 26: 3538–3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries PA, Pan A, Quatrano RS (2005) Actin-related protein2/3 complex component ARPC1 is required for proper cell morphogenesis and polarized cell growth in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 17: 2327–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK. (2005) Calcium: a central regulator of plant growth and development. Plant Cell 17: 2142–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK. (2016) The cytoskeleton and its regulation by calcium and protons. Plant Physiol 170: 3–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Rounds CM, Winship LJ (2013) Control of cell wall extensibility during pollen tube growth. Mol Plant 6: 998–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Winship LJ (2015) The pollen tube clear zone: clues to the mechanism of polarized growth. J Integr Plant Biol 57: 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiwatashi Y, Sato Y, Doonan JH (2014) Kinesins have a dual function in organizing microtubules during both tip growth and cytokinesis in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 26: 1256–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoedemaekers K, Derksen J, Hoogstrate SW, Wolters-Arts M, Oh SA, Twell D, Mariani C, Rieu I (2015) BURSTING POLLEN is required to organize the pollen germination plaque and pollen tube tip in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 206: 255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Vogler H, Aellen M, Shamsudhin N, Jang B, Burri JT, Läubli N, Grossniklaus U, Pané S, Nelson BJ (2017) High precision, localized proton gradients and fluxes generated by a microelectrode device induce differential growth behaviors of pollen tubes. Lab Chip 17: 671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Blanchoin L, Chaudhry F, Franklin-Tong VE, Staiger CJ (2004) A gelsolin-like protein from Papaver rhoeas pollen (PrABP80) stimulates calcium-regulated severing and depolymerization of actin filaments. J Biol Chem 279: 23364–23375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Qu X, Zhang R (2015) Plant villins: versatile actin regulatory proteins. J Integr Plant Biol 57: 40–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JU, Gu Y, Lee YJ, Yang Z (2005) Oscillatory ROP GTPase activation leads the oscillatory polarized growth of pollen tubes. Mol Biol Cell 16: 5385–5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ren J, Fujita T (2014) Conserved function of Rho-related Rop/RAC GTPase signaling in regulation of cell polarity in Physcomitrella patens. Gene 544: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jásik J, Mičieta K, Siao W, Voigt B, Stuchlík S, Schmelzer E, Turňa J, Baluška F (2016) Actin3 promoter reveals undulating F-actin bundles at shanks and dynamic F-actin meshworks at tips of tip-growing pollen tubes. Plant Signal Behav 11: e1146845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Shen JJ, Fu Y, Li H, Yang Z, Grierson CS (2002) The Arabidopsis Rop2 GTPase is a positive regulator of both root hair initiation and tip growth. Plant Cell 14: 763–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Zheng M, Zhang Y, Yuan M, Yalovsky S, Zhu L, Fu Y (2017) The microtubule-associated protein MAP18 affects ROP2 GTPase activity during root hair growth. Plant Physiol 174: 202–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T. (2013) The actin cytoskeleton in root hairs: all is fine at the tip. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, de Ruijter NCA, Emons AMC (2003) Unstable F-actin specifies the area and microtubule direction of cell expansion in Arabidopsis root hairs. Plant Cell 15: 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana P, Henty JL, Huang S, Staiger AM, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ (2010) Arabidopsis VILLIN1 and VILLIN3 have overlapping and distinct activities in actin bundle formation and turnover. Plant Cell 22: 2727–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U, Becker C, Schmitt AC, Kost B (2006) Nt-RhoGDI2 regulates Rac/Rop signaling and polar cell growth in tobacco pollen tubes. Plant J 46: 1018–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U, Kost B (2006) Tobacco RhoGTPase ACTIVATING PROTEIN1 spatially restricts signaling of RAC/Rop to the apex of pollen tubes. Plant Cell 18: 3033–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost B, Lemichez E, Spielhofer P, Hong Y, Tolias K, Carpenter C, Chua NH (1999) Rac homologues and compartmentalized phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate act in a common pathway to regulate polar pollen tube growth. J Cell Biol 145: 317–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost B, Spielhofer P, Chua NH (1998) A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J 16: 393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Drøbak BK, Staiger CJ (2000) Maize profilin isoforms are functionally distinct. Plant Cell 12: 583–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T, Sparks JA, Nakashima J, Allen SN, Tang Y, Blancaflor EB (2015) Transcriptional response of Arabidopsis seedlings during spaceflight reveals peroxidase and cell wall remodeling genes associated with root hair development. Am J Bot 102: 21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport DTA, Várnai P (2013) Periplasmic arabinogalactan glycoproteins act as a calcium capacitor that regulates plant growth and development. New Phytol 197: 58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport DTA, Varnai P, Seal CE (2014) Back to the future with the AGP-Ca2+ flux capacitor. Ann Bot 114: 1069–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancelle SA, Hepler PK (1991) Association of actin with cortical microtubules revealed by immunogold localization in Nicotiana pollen tubes. Protoplasma 165: 167–172 [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Sakata Y, Mau SL, Pettolino F, Bacic A, Quatrano RS, Knight CD, Knox JP (2005) Arabinogalactan proteins are required for apical cell extension in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 17: 3051–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin B, Richter D, Markovich I, Zik M (2008) Arabinogalactan proteins 6 and 11 are required for stamen and pollen function in Arabidopsis. Plant J 56: 351–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Dong H, Pei W, Liu C, Zhang S, Sun T, Xue X, Ren H (2017) LlFH1-mediated interaction between actin fringe and exocytic vesicles is involved in pollen tube tip growth. New Phytol 214: 745–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Qu X, Jiang Y, Chang M, Zhang R, Wu Y, Fu Y, Huang S (2015) Profilin regulates apical actin polymerization to control polarized pollen tube growth. Mol Plant 8: 1694–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovy-Wheeler A, Kunkel JG, Allwood EG, Hussey PJ, Hepler PK (2006) Oscillatory increases in alkalinity anticipate growth and may regulate actin dynamics in pollen tubes of lily. Plant Cell 18: 2182–2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovy-Wheeler A, Wilsen KL, Baskin TI, Hepler PK (2005) Enhanced fixation reveals the apical cortical fringe of actin filaments as a consistent feature of the pollen tube. Planta 221: 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malho R, Trewavas AJ (1996) Localized apical increases of cytosolic free calcium control pollen tube orientation. Plant Cell 8: 1935–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna ST, Kunkel JG, Bosch M, Rounds CM, Vidali L, Winship LJ, Hepler PK (2009) Exocytosis precedes and predicts the increase in growth in oscillating pollen tubes. Plant Cell 21: 3026–3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendrinna A, Persson S (2015) Root hair growth: it’s a one way street. F1000Prime Rep 7: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli MA, Créton R, Jaffe LF, Robinson KR (2000) Periodic increases in elongation rate precede increases in cytosolic Ca2+ during pollen tube growth. Dev Biol 222: 84–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michard E, Lima PT, Borges F, Silva AC, Portes MT, Carvalho JE, Gilliham M, Liu LH, Obermeyer G, Feijó JA (2011) Glutamate receptor-like genes form Ca2+ channels in pollen tubes and are regulated by pistil D-serine. Science 332: 434–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michard E, Simon AA, Tavares B, Wudick MM, Feijó JA (2017) Signaling with ions: the keystone for apical cell growth and morphogenesis in pollen tubes. Plant Physiol 173: 91–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollet JC, Kim S, Jauh GY, Lord EM (2002) Arabinogalactan proteins, pollen tube growth, and the reversible effects of Yariv phenylglycoside. Protoplasma 219: 89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Bibikova TN, Messerli MA, Shi C, Gilroy S (2007) Oscillations in extracellular pH and reactive oxygen species modulate tip growth of Arabidopsis root hairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 20996–21001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Messerli MA, Gilroy S (2008) Imaging of the Yellow Cameleon 3.6 indicator reveals that elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ follow oscillating increases in growth in root hairs of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 147: 1690–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaoka Y, Kimura A, Tani T, Goshima G (2015) Cytoplasmic nucleation and atypical branching nucleation generate endoplasmic microtubules in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 27: 228–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida E, Iida K, Yonezama N, Koyasu S, Yahara I, Sakai H (1987) Cofilin is a component of intranuclear and cytoplasmic actin rods induced in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 5262–5266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olyslaegers G, Verbelen JP (1998) Improved staining of F-actin and co-localization of mitochondria in plant cells. J Microsc 192: 73–77 [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Nebenführ A (2013) Myosin XIK of Arabidopsis thaliana accumulates at the root hair tip and is required for fast root hair growth. PLoS ONE 8: e76745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Braybrook S, Höfte H (2012) Cell wall mechanics and growth control in plants: the role of pectins revisited. Front Plant Sci 3: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Braybrook SA, Le Guillou L, Bron E, Kuhlemeier C, Höfte H (2011) Pectin-induced changes in cell wall mechanics underlie organ initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 21: 1720–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Wightman R, Höfte H (2015) The control of growth symmetry breaking in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Curr Biol 25: 1746–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud PF, Quatrano RS (2006) The role of ARPC4 in tip growth and alignment of the polar axis in filaments of Physcomitrella patens. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 63: 162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud PF, Quatrano RS (2008) BRICK1 is required for apical cell growth in filaments of the moss Physcomitrella patens but not for gametophore morphology. Plant Cell 20: 411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Zhang H, Xie Y, Wang J, Chen N, Huang S (2013) Arabidopsis villins promote actin turnover at pollen tube tips and facilitate the construction of actin collars. Plant Cell 25: 1803–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Zhang R, Zhang M, Diao M, Xue Y, Huang S (2017) Organizational innovation of apical actin filaments drives rapid pollen tube growth and turning. Mol Plant 10: 930–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PM. (1992) Mechanisms of wall loosening for cell growth. Current Topics in Plant Biochemistry and Physiology 11: 18–41 [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb Z, et al. (2008) Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat Methods 5: 605–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röckel N, Wolf S, Kost B, Rausch T, Greiner S (2008) Elaborate spatial patterning of cell-wall PME and PMEI at the pollen tube tip involves PMEI endocytosis, and reflects the distribution of esterified and de-esterified pectins. Plant J 53: 133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds CM, Hepler PK, Winship LJ (2014) The apical actin fringe contributes to localized cell wall deposition and polarized growth in the lily pollen tube. Plant Physiol 166: 139–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds CM, Lubeck E, Hepler PK, Winship LJ (2011) Propidium iodide competes with Ca2+ to label pectin in pollen tubes and Arabidopsis root hairs. Plant Physiol 157: 175–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Jauh GY, Hepler PK, Lord EM (1998) Effects of Yariv phenylglycoside on cell wall assembly in the lily pollen tube. Planta 204: 450–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SJ, Holdaway-Clarke TL, Hackett GR, Kunkel JG, Lord EM, Hepler PK (1999) Uncoupling secretion and tip growth in lily pollen tubes: evidence for the role of calcium in exocytosis. Plant J 19: 379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan MB, Staiger CJ, Rose RJ, McCurdy DW (2004) A green fluorescent protein fusion to actin-binding domain 2 of Arabidopsis fimbrin highlights new features of a dynamic actin cytoskeleton in live plant cells. Plant Physiol 136: 3968–3978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieberer BJ, Ketelaar T, Esseling JJ, Emons AMC (2005) Microtubules guide root hair tip growth. New Phytol 167: 711–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan OOH. (2017) Actin fringes of polar cell growth. J Exp Bot 68: 3303–3320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Zhu J, Cai C, Pei W, Wang J, Dong H, Ren H (2012) FIMBRIN1 is involved in lily pollen tube growth by stabilizing the actin fringe. Plant Cell 24: 4539–4554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez C, Carroll RT, Burke TA, Christensen JR, Bestul AJ, Sees JA, James ML, Sirotkin V, Kovar DR (2015) Profilin regulates F-actin network homeostasis by favoring formin over Arp2/3 complex. Dev Cell 32: 43–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwińska A, Wasąg P, Zakrzewski P, Lenartowska M, Lenartowski R (2017) Calreticulin is required for calcium homeostasis and proper pollen tube tip growth in Petunia. Planta 245: 909–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synek L, Vukašinović N, Kulich I, Hála M, Aldorfová K, Fendrych M, Žárský V (2017) EXO70C2 is a key regulatory factor for optimal tip growth of pollen. Plant Physiol 174: 223–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski D, Staiger CJ (2018) The actin cytoskeleton: functional arrays for cytoplasmic organization and cell shape control. Plant Physiol 176: 106–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Showalter AM, Egelund J, Hernandez-Sanchez A, Doblin MS, Bacic A (2012) Arabinogalactan-proteins and the research challenges for these enigmatic plant cell surface proteoglycans. Front Plant Sci 3: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Cao K, Liu F, Li Y, Li P, Gao C, Ding Y, Lan Z, Shi Z, Rui Q, et al. (2016) Arabidopsis COG complex subunits COG3 and COG8 modulate Golgi morphology, vesicle trafficking homeostasis and are essential for pollen tube growth. PLoS Genet 12: e1006140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker EB, Lee M, Alli S, Sookhdeo V, Wada M, Imaizumi T, Kasahara M, Hepler PK (2005) UV-A induces two calcium waves in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 1226–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruaene N, Joss G, Van Oostveldt P (2004) Reorganization and in vivo dynamics of microtubules during Arabidopsis root hair development. Plant Physiol 136: 3905–3919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Honing HS, Kieft H, Emons AMC, Ketelaar T (2012) Arabidopsis VILLIN2 and VILLIN3 are required for the generation of thick actin filament bundles and for directional organ growth. Plant Physiol 158: 1426–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Honing HS, van Bezouwen LS, Emons AMC, Ketelaar T (2011) High expression of Lifeact in Arabidopsis thaliana reduces dynamic reorganization of actin filaments but does not affect plant development. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 68: 578–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez LAB, Sanchez R, Hernández-Barrera A, Zepeda-Jazo I, Sanchez F, Quinto C, Torres LC (2014) Actin polymerization drives polar growth in Arabidopsis root hair cells. Plant Signal Behav 9: e29401–e29404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Augustine RC, Kleinman KP, Bezanilla M (2007) Profilin is essential for tip growth in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 19: 3705–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Burkart GM, Augustine RC, Kerdavid E, Tüzel E, Bezanilla M (2010) Myosin XI is essential for tip growth in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 22: 1868–1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Hepler PK (1997) Characterization and localization of profilin in pollen grains and tubes of Lilium longiflorum. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 36: 323–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, McKenna ST, Hepler PK (2001) Actin polymerization is essential for pollen tube growth. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2534–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, Rounds CM, Hepler PK, Bezanilla M (2009a) Lifeact-mEGFP reveals a dynamic apical F-actin network in tip growing plant cells. PLoS ONE 4: e5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L, van Gisbergen PAC, Guérin C, Franco P, Li M, Burkart GM, Augustine RC, Blanchoin L, Bezanilla M (2009b) Rapid formin-mediated actin-filament elongation is essential for polarized plant cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 13341–13346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler F, Konrad SSA, Sprunck S (2015) Knockin’ on pollen’s door: live cell imaging of early polarization events in germinating Arabidopsis pollen. Front Plant Sci 6: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu L, Liu B, Wang C, Jin L, Zhao Q, Yuan M (2007) Arabidopsis MICROTUBULE-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN18 functions in directional cell growth by destabilizing cortical microtubules. Plant Cell 19: 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YF, Fan LM, Zhang WZ, Zhang W, Wu WH (2004) Ca2+-permeable channels in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis pollen are regulated by actin microfilaments. Plant Physiol 136: 3892–3904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship LJ, Rounds C, Hepler PK (2016) Perturbation analysis of calcium, alkalinity and secretion during growth of lily pollen tubes. Plants (Basel) 6: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Gu Y, Li S, Yang Z (2001) A genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis Rop-interactive CRIB motif-containing proteins that act as Rop GTPase targets. Plant Cell 13: 2841–2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Qu H, Jin C, Shang Z, Wu J, Xu G, Gao Y, Zhang S (2011) cAMP activates hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+ channels in the pollen of Pyrus pyrifolia. Plant Cell Rep 30: 1193–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SZ, Bezanilla M (2014) Myosin VIII associates with microtubule ends and together with actin plays a role in guiding plant cell division. eLife 3: 3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Wang S, Wu C, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Li Y, Hao L, Gu Z, Li W, et al. (2017) Malus domestica ADF1 severs actin filaments in growing pollen tubes. Funct Plant Biol 44: 455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Zhang R, Qu X, Huang S (2016) Arabidopsis FIM5 decorates apical actin filaments and regulates their organization in the pollen tube. J Exp Bot 67: 3407–3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Pan Y, Tian W, Dong M, Zhu H, Luan S, Li L (2017) Arabidopsis CNGC14 mediates calcium influx required for tip growth in root hairs. Mol Plant 10: 1004–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Zhang Y, Kang E, Xu Q, Wang M, Rui Y, Liu B, Yuan M, Fu Y (2013) MAP18 regulates the direction of pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis by modulating F-actin organization. Plant Cell 25: 851–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]