Abstract

Snake envenomation is a global problem and often a matter of life or death. Emergency treatment is not always readily available or effective. There are numerous neurotoxic snakes in the Americas, chiefly elapids; some crotalids have also evolved neurotoxic venom. The variability of neurotoxins found in snake venom within the same species makes development and choice of proper antivenom a major challenge that has not been completely addressed. This article reviews the epidemiology, clinical effects, and current treatment of neurotoxic snake envenomation in the Americas.

Approximately 3,000 species of snakes live in various climates around the world and about 375 of these species are venomous, with a smaller number potentially dangerous to humans. A majority of the venoms that may have an effect on people are hemotoxic. A smaller proportion have neurotoxic effects. In the Americas, people live in and visit areas that are the natural habitat of venomous snakes.

Venomous snakes and humans

Although some cultures revere snakes as gods or mystical symbols, in general, people fear snakes. In many places around the globe, people live in close proximity to venomous snakes, while in other regions, people are more likely to experience chance encounters during outdoor recreation. Humans are not the snake's prey, and snakes generally try to avoid people. Bites typically occur when a person surprises or plays with a snake. In North America, bites are most often seen in children who try to play with snakes or adults under the influence of alcohol. In lesser developed countries, the circumstances may involve people working in fields or living in homes that are less secure from a snake crawling in and being surprised.

Envenomation occurs when a snake bite results in venom being injected into the victim by the snake. Annual cases of envenomation1 are estimated to be as high as 1.14/100,000 population in North America, 20.6/100,000 in the Caribbean, 30.47/100,000 in Central America and, 24.74/100,000 in South America (South American numbers are averaged from all regions). Deaths due to snake bite are uncommon, with an estimated high of 0.002/100,000 population in North America, 2.98/100,000 population in the Caribbean, 0.661/100,000 population in Central America, and 0.403/100,000 population in South America. Estimates of envenomation from snake bite globally suggest that only about one third of all snake bites result in envenomation,1 with the remainder being dry bites. Considering the low number of deaths, envenomation is generally survivable.

Between 2001 and 2010, an average of 9,165 snake bites were seen in US emergency departments annually, of which only 2,825 were from venomous snakes.2 Another study found a similar annual snake bite rate and about 30% of snake bites were reported as venomous3 (although lay person identification may not be accurate). In the 20-year period in the United States from 1979 to 1998, only 97 deaths occurred due to snake bite.4 Other countries do not fare as well. Data from other countries show the incidence of snake bite is much higher, likely due to living and working conditions. The highest incidence is in India and Southeast Asia, followed by Sub-Saharan Africa and the Amazon region.1 India had an estimated 14,112 to 33,666 deaths by snake bite in 2007.1

Neurotoxic snakes, venom diversity, and composition

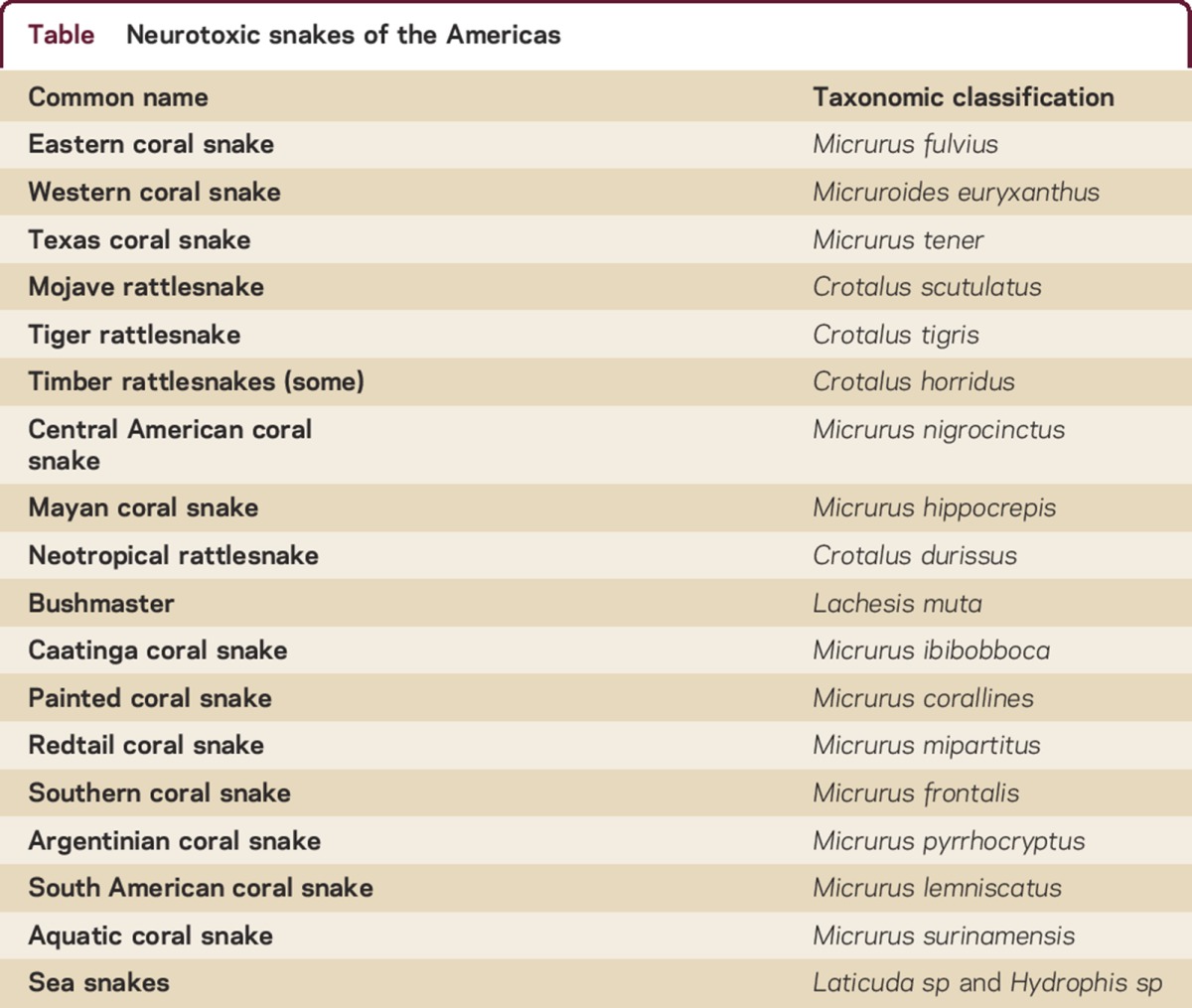

Coral snakes are elapids (family Elapidae, genus Micrurus and Micruroides) and range throughout the Americas, with the majority being found in Central and South America (table). In North America, the eastern coral snake is found along the Florida and Georgia coasts, the Texas coral snake lives along the Texas coast, and the western coral snake lives in southern Arizona and northern Mexico. The Central American coral snake is located on a few western Caribbean islands and in Central America. Central and South America are home to the remainder of the list, with sea snakes found only in Pacific waters.

Table Neurotoxic snakes of the Americas

The other poisonous snakes of the Americas are crotalids, which belong to the pit viper family. The majority of these snakes have predominantly hemotoxic venom, but a few species are predominantly neurotoxic. These are the Mojave rattlesnake found in the southwestern United States, a few timber rattlesnakes of the southeastern United States, the tiger rattlesnake in the Sonoran desert, the neotropical rattlesnake of Central America, and the bushmaster of South America.

Snake venom composition varies greatly even within the same geographic region and may be composed of differing amounts of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), 3 finger toxins (3FTx), metalloproteinase, hyaluronidase, phosphodiesterase, acetylcholinesterase, L-amino acid dehydrogenase, and L-amino acid oxidase,5 all of which are proteins with different functions: myotoxins, cardiotoxins, enzymes that damage endothelium, hemotoxins (promote thrombosis, hemorrhage, and red blood cell destruction), and neurotoxins (pain, paresthesia, and paralysis). Venom also contains proteolytic enzymes that digest the prey, allowing the snake to consume its meal whole. Because of the complex variety of toxins in snake venom, scientifically it may not be precise to classify them as hemotoxic or neurotoxic (as has been classically done). However, this terminology is clinically useful to evaluate and monitor the major effects of venom on patients, and to help determine the best course of treatment.

In general, 3FTx and PLA2 block nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, while acetylcholinesterase degrades the neurotransmitter, with weakness resulting. PLA2s may also affect the function of synaptic vesicles, interfering with synaptophysin and synaptobrevin and preventing normal function of the snare protein in vesicular membrane fusion.6 The net effect is a reduction of motor end-plate activation to contract the muscle and weakness results, similar to myasthenia gravis. Any muscle may be affected and when the neuromuscular blockade involves muscles of respiration, death ensues.

An analysis7 of the venom composition and activity of 9 species of micrurus found throughout the Americas reported considerable variation as well as nonresponse to commonly used antivenoms. The authors concluded that the antitoxins used for micrurus envenomation were not effective for all micrurus species, even within the same region. Similar diversity has been found in other studies as well,5,8–10 demonstrating that antivenom for an elapid genus/species may work in one region and not another region, even within the same country.

Some species of crotalids have also evolved considerable neurotoxic components,11–15 making treatment of envenomation with the correct antivenom challenging when several species of rattlesnakes coexist in the same area. Timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) venom is a good example. This species usually has hemotoxic venom, but in the regions of the southeastern United States, where its range overlaps with the coral snake,16 it has evolved primarily neurotoxic venom. The Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutalatus) is a pit viper with variable hemotoxic and neurotoxic (Mojave) venom. The neurotoxic component is greater in northern Mexico than in the same species just over the border into the southwestern United States.13

A review17 of dozens of articles on venomics concluded that there is a great deal more variation in snake venom composition, even within the same species and same region, than generally has been believed. This variation may lead to treatment failures with currently available antivenoms. A better approach to treatment of venomous snake bite may involve a detailed analysis of the venom, and not the traditionally used geographic and phylogenetic-driven treatment algorithms.17

Treatment of neurotoxic snake envenomation

In the past, efforts to treat any snakebite included applying a tourniquet and cutting the puncture marks followed by sucking out the poison or the use of electricity on the bite marks. None of these strategies has proven effective and may actually cause harm. More recently, the application of a vacuum extractor was thought to be beneficial, but has fallen out of favor.18

For elapid envenomation, the field application of an elastic bandage to the affected extremity has been suggested,19,20 but in practice, wrapping a limb to produce the correct pressure is difficult to achieve21,22 and any benefit is lost if the limb is mobilized for as little as 10 minutes after application.23

The WHO has advocated for a trial of anticholinesterase treatment for elapid envenomation that reasonably demonstrates neuromuscular weakness24,25 and a recent case report suggests that intranasal administration of neostigmine may be a reasonable field treatment of neurotoxic envenomation while arranging transport to a higher level of care.26

Field emergency treatment (of any venomous snakebite) involves first making certain that the snake is gone from the area, so that the rescuers do not become additional victims. The victim should be kept calm and the affected limb immobile. Remove all jewelry and constricting clothing items from the victim. Obtain as much information about the snake as possible to assist in selecting the optimal antivenom at the treating facility. If possible, take a photograph (from a safe distance). Write down descriptive details about the snake to help with species identification and make note of the geographic location in which the bite occurred.

The victim must be transported to an emergency facility as soon as possible, and in a wilderness setting this may mean carrying the victim out. If the location or terrain is prohibitive, or there are not enough people available to carry the patient, then the victim will have to walk out. This should be done slowly but deliberately in an attempt to balance the need to get to help with the need to keep venom circulation to a minimum. There are no easy answers for this issue.

Once the victim is at a higher level of care, an attempt is made to identify the snake using a photograph or a description including color, eye shape, and head shape. Determination of bite severity has been advocated27–29 to decide if antivenom is indicated. In practice, it is likely that most, if not all, bite victims will receive antivenom if available. Recommendations are to start the antivenom as soon as possible after the bite and before neuromuscular symptoms begin.

Coral snake antivenom has not been produced in the United States since 2003. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) extended the expiration date on the one available lot twice but that expired as of April 30, 2015. The Venom Immunochemistry, Pharmacology and Emergency Response (VIPER) Institute of the University of Arizona is conducting a phase 3 NIH-supported clinical trial (NCT01337245) of a new antivenom, anti F(ab'). This trial is scheduled to be completed in March 2016. A potential substitute, Coralmyn (Instituto Bioclon, Mexico City, Mexico) exists, but is not FDA-approved for use in the United States.

Crotalid antivenom (Crofab, BTG International, Conshohocken, PA) is given in North America for pit viper envenomation, and contains antivenom to 4 snakes found in the United States, including the neurotoxic Mojave rattlesnake (C scutulatus). In Latin America, the antivenom supply availability, use, and quality varies between different regions.30

Response to antivenom is variable due to several factors. One is the time lapse between the envenomation and the administration of antivenom. A second is whether or not a toxic dose of the venom was received. A third variable is which specific toxins are present in the venom that may not be accounted for in the antivenom, a possibility suggested by research demonstrating toxin variability in snakes of the Western hemisphere.17

Given the relatively small annual numbers of neurotoxic snake envenomation in developed countries, it is uncertain if sufficient research effort and money will ever be expended to determine the best means of treatment. In developing countries, where a majority of envenomation occurs, a lack of research and development money and diversity of population and snake species may be the major inhibitors to adequate treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Drafting/revising the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

T.D. Rolan serves on the editorial board for Neurology: Clinical Practice. Full disclosure form information provided by the author is available with the full text of this article at http://cp.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000180.

Correspondence to: terry.rolan@va.gov

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article. Full disclosure form information provided by the author is available with the full text of this article at http://cp.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000180.

Footnotes

Correspondence to: terry.rolan@va.gov

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article. Full disclosure form information provided by the author is available with the full text of this article at http://cp.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000180.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5:1591–1604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langley R, Mack K, Haileyesus T. National estimates of non-canine bite and sting injuries treated in US hospital emergency departments 2001–2010. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014;25:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill ME, Mack KA, Gilchrist J, Wozniak EJ. Snakebite injuries treated in United States emergency departments, 2001–2004. Wilderness Environ Med. 2007;18:281–287. doi: 10.1580/06-WEME-OR-080R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan BW, Lee C, Damiano L, Whitlow K, Geller R. Reptile envenomation 20-year mortality as reported by US medical examiners. South Med J. 2004;97:642–644. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciscotto PHC, Rates B, Silva DAF. Venomic analysis of antivenom cross-reactivity of South American micrurus species. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1810–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treppmann P, Brunk I, Afube T, Richter K, Ahnert-Hilger G. Neurotoxic phospholipases directly affect synaptic vesicle function. J Neurochem. 2011;117:757–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka GD, Furtado Mde D, Portaro FC, Sant'Anna OA, Tambourgi DV. Diversity of micrurus snake species related to their venom toxic effects and the prospective of antivenom neutralization. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:622–634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergara I, Pedraza-Escalona M, Paniagua D. Eastern coral snake Micrurus fulvius venom toxicity in mice is mainly determined by neurotoxic phospholipases A2. J Proteomics. 2014;105:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bénard-Valle M, Carbajal-Saucedo A, de Roodt A, López-Vera E, Alagón A. Biochemical characterization of the venom of the coral snake Micrurus tener and comparative biological activities in the mouse and a reptile model. Toxicon. 2014;77:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrêa-Netto C, Junqueira-de-Azevedo Ide L, Silva DA. Snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of Brazilian coral snakes, Micrurus altirostris and M corallines. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvete JJ, Perez A, Lomonte B, Snachez EE, Sanz L. Snake venomics of Crotalus tigris: the minimalist toxin arsenal of the deadliest Nearctic rattlesnake venom: evolutionary clues for generating a pan-specific antivenom against crotalid type2 venoms. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1382–1390. doi: 10.1021/pr201021d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rokyta DR, Wray KP, Margres MJ. The genesis of an exceptionally lethal venom in the timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) revealed through comparative venom-gland transcriptomics. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:394–415. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massey DJ, Calvete JJ, Sanchez EE. Venom variability and envenomating severity outcomes of the Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus (Mojave rattlesnake) from Southern Arizona. J Proteomics. 2012;75:2576–2587. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magres M, McGivern JJ, Wray K, Seavy M, Calvin K, Rokyta DR. Linking the transcriptome and proteome to characterize the venom of the eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) J Proteomics. 2014;96:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgieva D, Ohler M, Seifert J. Snake venomic of Crotalus durissus terrificus: correlation with pharmacological activities. J Proteosome Res. 2010;9:2302–2316. doi: 10.1021/pr901042p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glenn JL, Straight RC, Wolt TB. Regional variation in the presence of canebrake toxin in Crotalus horridus venom. Comp Biochem Physiol Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1994;107:337–346. doi: 10.1016/1367-8280(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvete JJ. Snake venomics: from the inventory of toxins to biology. Toxicon. 2013;75:44–62. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberts MB, Shalit M, LoGalbo F. Suction for venomous snakebite: a study of “mock venom” extraction in a human model. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:181–186. doi: 10.1016/S0196064403008138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auerbach PS, Constance DB, Freer L, eds. Field Guide to Wilderness Medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia: PA Elsevier Press; 2013:440–442.

- 20.Stewart C. Snake bite in Australia: first aid and envenomation management. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2003;11:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2302(02)00189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norris RL, Ngo J, Nohan K, Hooker G. Physicians and lay people are unable to apply pressure immobilization properly in a simulated snakebite scenario. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:16–21. doi: 10.1580/PR12-04.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson ID, Tanwar PD, Andrade C, Kochar DK, Norris RL. The Ebbinghaus retention curve: training does not increase the ability to apply pressure immobilization in simulated snake bite: implications for snake bite first aid in the developing world. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howarth DM, Southee AS, Whyte IM. Lymphatic flow rates and first aid in simulated peripheral snake or spider envenomation. Med J Aust. 1994;161:695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Guidelines for the Management of Snake Bites. 2010:106. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js17111e/. Accessed August 13, 2015.

- 25.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Guidelines for the Prevention and Clinical Management of Snake Bite in Africa. 2010:87–88. Available at: http://www.afro.who.int/en/clusters-a-programmes/hss/essential-medicines/highlights/2731-guidelines-for-the-prevention-and-clinical-management-of-snakebite-in-africa.html. Accessed August 13, 2015.

- 26.Lewin MR, Bickler P, Heier T. Reversal of experimental paralysis in a human by intranasal neostigmine suggests a novel approach to the early treatment of neurotoxic envenomation. Clin Case Rep. 2013;1:7–15. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otten EJ. Venomous animal injuries. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine, 8th ed. Saunders; 2014:794–807.

- 28.Lavonas EJ, Gerardo CJ, O'Malley G. Initial experience with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab (ovine) antivenom in the treatment of copperhead snakebite. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dart RC, Seifert SA, Boyer LV. A randomized multicenter trial of crotalidae polyvalent immune fab (ovine) antivenom for the treatment of crotaline snakebite in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2030–2036. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutiérrez JM, Fan HW, Silvera CL, Anqulo Y. Stability, distribution and use of antivenoms for snakebite envenomation in Latin America: report of a workshop. Toxicon. 2009;53:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]