Summary

In order to carry out biological functions, RNA molecules must fold into specific three-dimensional (3D) structures. Current experimental methods to determine RNA 3D structures are expensive and time consuming. With the recent advances in computational biology, RNA structure prediction is becoming increasingly reliable. This chapter describes a recently developed RNA structure prediction software, Vfold, a virtual bond-based RNA folding model. The main features of Vfold are the physics-based loop free energy calculations for various RNA structure motifs and a template-based assembly method for RNA 3D structure prediction. For illustration, we use the yybP-ykoY Orphan riboswitch as an example to show the implementation of the Vfold model in RNA structure prediction from the sequence.

Keywords: RNA folding, Vfold model, loop entropy, template assembly

1. Introduction

Current experimental methods, such as X-ray crystallography (1), NMR (2) and electron microscopy (3), can determine RNA 3D structures in high or low resolutions. However, using experimental methods to determine RNA structures can be expensive and time consuming. With the rapid advances of RNA sequencing technology (4), experimental methods may not catch up the demands for high resolution RNA 3D structures. Therefore, computational structure prediction becomes a highly needed tool for RNA biology.

An RNA structure can be described at 2D and 3D levels. A 2D structure is defined by the base pairs contained in the structure, which provides structural constrains for 3D structure folding. Current RNA 2D structure prediction algorithms can be classified into two major categories (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10): sequence alignment-based methods and free energy-based methods. In general, sequence alignment software, such as Dynalign (11), gives reliable 2D structures if homologous sequences are available. However, many alternative structures, which may not be predicted by the comparative sequence analysis method, can also be functionally important. For example, riboswitches undergo a conformational change in response to binding of a regulatory molecule (12). Free energy-based methods, such as Mfold (13), RNAstructure (14), and RNAfold (15), calculate the free energies for an ensemble of structures and find the minimum free energy structure or the most probable (average) structure. One of the key ingredients of these methods is the availability of thermodynamic parameters for loops and helices. The thermodynamic parameters for helices and simple loops (i.e. small-size hairpin, internal/bulge loops) have been determined systematically and compiled as the Turner’s parameters (16). However, free energy parameters of other more complicated loops remain unknown and need to be determined through a computational model.

Knowing RNA 2D structure is not sufficient to obtain high resolution 3D structure. In general, a 2D structure can correspond to a large number of 3D structures due to the multiplicity of flexible loop conformations. We still need methods to model the structures of the unpaired nucleotides and the relative orientations of helices. There are many different ways to predict RNA 3D structures from given 2D structure. For example, one such method is to use knowledge-based force field and predict RNA 3D structures from coarse-grained discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) simulations (17, 18, 19, 20). Here the coarse-grained representation for RNA conformations can dramatically decrease the number of freedoms of an RNA system, and thus increase the completeness of the conformational sampling. One of the major issues in the simulations is that the sampled conformations often remain close to the initial starting model, which requires the use of various special simulation techniques to achieve effective sampling of conformational space. One of the attempts to circumvent this problem is to use template-based structure prediction algorithm (21, 22, 23, 24). For the template-based approaches, one of the common limitations is the limited degree of divergence of the template library. Given the limited number of known RNA structures, structural motif templates with the required high sequence similarity are difficult to attain. The lack of reliable structural motifs for many loops and junctions has greatly hampered our effort for successful 3D structure prediction. Nevertheless, as more and more RNA structures are experimentally determined, we can realistically expect the continuous improvements in the accuracy of structure prediction using template-based prediction algorithms.

The recently developed Vfold model (23, 24, 25, 26) is a free energy-based RNA folding model to predict RNA structures and thermodynamic stabilities from the sequence. Compared with other RNA structure prediction software (13, 14, 15, 22), Vfold uses a coarse-grained representation (24, 25) for RNA conformations. The model enumerates all the possible loop conformations in 3D space to calculate loop entropy and free energy parameters. For the 3D structure prediction, Vfold uses template-based method to assemble RNA 3D structures from motifs. In this chapter, we illustrate the application of the Vfold software/web server (24) in RNA structure prediction.

2. Algorithms

2.1 Computation of loop entropies and prediction of 2D structure (Vfold2D)

Vfold model uses two virtual bonds (P-C4′ and C4′-P) per nucleotide to represent RNA backbone configurations (see Fig. 1). By enumerating all the possible virtual-bond conformations in the 3D space (see Note 1), Vfold estimates the loop entropy parameters from the probability of loop closure (24, 25). The model has the advantage of accounting for chain connectivity, excluded volume (between loops and helices), and the completeness of virtual-bonded loop conformational ensemble. Vfold2D (24) is a free energy-based model that predicts RNA 2D structures using the above Vfold-derived entropy and free energy parameters

Figure 1.

The Vfold model uses two bonds (P-C4′ and C4′-P) to represent each nucleotide and computes loop entropies by sampling virtual-bonded conformations in 3D space. (a) Virtual-bonded representation of an RNA nucleotide. (b) The bond angles (βc, βp) and the torsional angles (θ, η) for the virtual bonds. Vfold enumerates RNA backbone conformations on a diamond lattice with bond length of 3.9 Å, bond angle of ~109.5° and three equiprobable torsional angles (60°, 180°, 300°). (c) A schematic diagram for a pseudoknotted loop. (d) A virtual-bonded pseudoknotted loop structure with all-atom helices.

Here, we use the pseudoknotted loop structure to illustrate the calculation for the Vfold entropy parameters. A pseudoknotted motif, as shown in Fig. 1c, consists of two helical stems and three loops. The relative orientation of the two helices can be configured by the 3D conformation of the L2 loop. Loops and helices can be correlated. For example, the loop conformations are constrained by the loop-helix volume exclusion, and the helix orientations can be determined from the coordinates of the nucleotides (a, b, c, d, e, and f in Fig. 1c) in the loop. Therefore, the free energy change, especially the entropic decrease, for the formation of the pseudoknotted loop structure depends not only on the lengths of the single-stranded loops L1, L2, and L3 but also on the lengths of the helices H1, and H2. Since the two virtual bonds per nucleotide used in Vfold model describe only the backbone structures, the Vfold-derived loop entropy parameters do not account for the sequence dependence per se (see Note 2). However, by explicitly enumerating the sequence-dependent intraloop structures (such as mismatches) for the loops, the Vfold2D model can (partially) account for the sequence-dependence of the loop free energy. The computation of the loop entropy parameters in the Vfold2D model involves the following three steps.

We sample helix configurations by enumerating the virtual-bond conformations of loop L2. The connection between the A-form helices and the discrete loop conformations is realized through an iterative optimized algorithm (27). Helices are modeled as the all-atom A-form (28) helix structures (see Note 3).

For each helix orientation, with the given (a, b) of the starting and ending nucleotides for loop L1 and (e, f) of the starting and ending nucleotides for loop L3, we sample loop conformations as self-avoiding walks of the virtual bonds on the diamond lattice to sample loops/junctions 3D conformations (see Note 4).

We estimate the loop entropy parameter as the logarithm of the probability of loop formation: ΔSloop = kB ln(Ωloop/Ωcoil) (see Note 2). Here Ωloop and Ωcoil are the conformational counts of the loop and the coil structures, respectively and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

With the Vfold-derived loop entropy parameters (25, 29, 30, 31, 32) and the experimentally determined base stacking thermodynamic parameters (16), Vfold2D (24) gives the free energy for each 2D structure and hence predicts the minimum free energy structure and the possible alternative metastable structures.

2.2 VfoldMTF: a database of RNA 3D motifs

To predict the 3D structure from the 2D structure using the knowledge about the known structures, we need to construct a database for all the known structural motifs. We have complied a database “VfoldMTF” (see http://rna.physics.missouri.edu/vfoldMTF/) for the 3D structural motifs, including hairpin loops, internal/bulge loops, N-way junctions (2 < N < 8), H-type pseudoknots, hairpin/hairpin kissing motifs, and 2-way/hairpin kissing motifs (see Fig. 2). The database shows the sequence of each motif as well as the PDB IDs of all the PDB entries that contain the motif. Currently, the raw database for the 3D motifs is built from 2626 known RNA 3D structures, including all the structures involving RNA (except for RNA/DNA hybrids). With the increasing number of PDB entries, the VfoldMTF database will be continuously updated.

Figure 2.

Snapshot of the VfoldMTF database. “Motif annotation” denotes the definition of the motifs. Users can search for motifs (with given loop sizes, optional) within the database. The output of VfoldMTF gives the information about the sequences and the strand(s), as well as the PDB id(s). For example, the 5-way junction with loop sizes 0-2-1-1-2 in the structure 3zjv (PDB id) can also be found in 4as1, 4cqn, and 3zgz. The information may be helpful for structure-function analysis.

Here are the methods to extract motif templates from known RNA 3D structures and build a non-redundant 3D motif database:

For a given RNA 3D structure (see Note 5), extract the A-form helices (see Note 6).

Determine the corresponding 2D structure for the given 3D structure based on the helices and loops.

Identify all the non-helix 2D structure motifs (such as hairpin loop, internal loop, three-way junction, H-type pseudoknot, …).

Remove the redundant templates for those with RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) < 1.5 Å for the same motif type and same sequence.

Collect all the non-redundant templates to construct an RNA 3D motif database.

This new database distinguishes itself from other database (33, 34, 35, 36) in the treatment of mismatches and other non-canonical interactions. For example, we consider nucleotides involved in the non-canonical base pairs (mismatches) as unpaired nucleotides. In addition, we classify motifs according to loop types (such as hairpin loops, N-way junctions, hairpin-hairpin kissing motifs, …) and their sizes instead of the type of intra-loop interactions (see Fig. 2). The database can be used not only for the motif template-assembly method for RNA 3D structure prediction, but also for the analysis of structure-function relationships.

2.3 3D structure prediction through motif-template assembly (Vfold3D)

Vfold3D, a package of Vfold for RNA 3D structure prediction, uses the template-based method to build RNA 3D structures (23, 24). Compared with other similar approaches, such as FARNA (21) and MC-Sym (22), Vfold3D uses motif-based templates instead of fragment-based templates. The method can account for the intra-motif interactions (see Note 7). Predicting the 3D structures from the sequence and the 2D structure (base pairs) involves the following steps.

Vfold3D first extracts motifs (such as helices (see Note 8), hairpin loops, internal/bulge loops, N-way junctions, …) from the given 2D structure.

Helices are modeled as the A-form virtual-bonded helix structures.

For the non-helix motifs, Vfold3D searches for the best templates from the VfoldMTF database to identify the appropriate template structures. The search criteria are based on the size (first) and sequence (second) matches (see Note 9). If necessary, this step may involve sequence replacement and base pair(s) insertion or deletion in order to match the templates in the database.

Vfold3D assembles the helix and loop 3D virtual-bonded structures to construct the 3D scaffold of the whole RNA.

Vfold3D adds all atoms to the virtual-bonded structure. For nucleotides in each helix, atoms are added according to the A-form helix atomic structure. The all-atom nucleotides in loops are generated by adding atoms according to the templates for base configurations.

The assembled all-atom structures are refined by the all-atom energy minimization (see Note 10).

3. Methods

To predict RNA 3D structures, Vfold first predicts the 2D structures from the sequence through the Vfold2D package. Using the 2D structures as constraint, the model then predicts the corresponding 3D structures from the Vfold3D package. The Vfold web server is freely accessible at http://rna.physics.missouri.edu.

3.1 To predict RNA 2D structures with Vfold2D

Vfold2D uses the Vfold-derived pre-tabulated loop entropy parameters (25, 29, 30, 31, 32) (see Note 11) to evaluate loop stability for each of the sampled structure. Currently, the Vfold2D server can predict RNA 2D structures for (a) secondary (non cross-linked) structure ensemble of sequence length less than 300 nucleotides and (b) H-type pseudoknotted structure ensemble of length less than 150 nucleotides, due to the long computational time. In addition to the lowest free energy structure, Vfold2D can also predict alternative structures.

Visit the Vfold2D server at (http://rna.physics.missouri.edu/vfold2D).

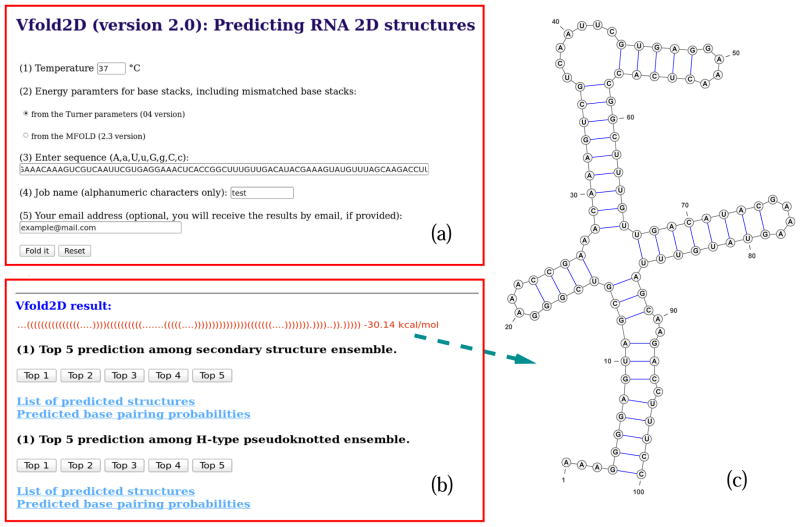

The input of Vfold2D (see Fig. 3a) contains RNA sequence (A,a,U,u,G,g,C,c letters only), temperature in Celsius and the choice of the energy parameters for base stacks (including mismatched stacks), which can be either from the Turner’s parameters (04 version) (16) or the MFOLD (2.3 version) (13) (see Note 12).

The computational time of Vfold2D depends on the length of input sequence (see Note 13). We recommend users to provide emails before submission, so the Vfold2D predictions can be delivered when the computation is finished.

Once the calculation is finished, users can retrieve the Vfold2D predictions either from the job-specific result page, as shown in Fig. 3, or from the email. Depending on the length of the input sequence, Vfold2D outputs up to two sets of predictions (for secondary and H-type pseudoknotted structures, respectively), with a list of predicted alternative structures and the base pairing probabilities (see Note 14).

Users can also check the top 5 (if available) 2D structures, plotted by VARNA (37), for each set of the predicted structures on the result page (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

An example of the Vfold2D prediction. (a) Input interface of Vfold2D server. Users have options to input sequence, temperature and choose base stack parameters for helices. (b) Output interface of Vfold2D server. Depending on the length of the input sequence, there are up to two sets of predictions (secondary and H-type pseudoknotted structures, respectively), with a list of predicted structures and the base pairing probabilities, included in the result page. For clarity, the 2D structure of the top 1 prediction is shown in (c).

We use the yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitch (38) (PDB:4y1i) as an example to illustrate the Vfold2D prediction. As shown in Fig. 3a, the input of Vfold2D is the 100-nucleotide long sequence (see Note 15), with the temperature of 37°C and the helix energy parameters from the Turner’s (04 version) parameters. Vfold2D outputs two sets of predicted results. The most probable 2D structure is the top 1 prediction from the secondary structure ensemble, as shown in Fig. 3c, which has the free energy of −30.14 kcal/mol. Compared with the native 2D structure (38) (see Note 16), Vfold2D correctly predicts 28 of 33 (84.8%) canonical base pairs in the native one.

3.2 To predict RNA 3D structures with Vfold3D

With the predicted 2D structure by Vfold2D (see Note 17), users can predict the 3D structures using the Vfold3D web server. Due to the limited divergence of the current VfoldMTF database, the current version of Vfold3D can only predict RNA 3D structures with hairpin loops, junctions, and limited number of pseudoknotted motifs.

Vfold3D web server is accessible at (http://rna.physics.missouri.edu/vfold3D).

The input of Vfold3D is the RNA sequence and the corresponding 2D structure (base pair information) in dot-bracket format (see Fig. 4a).

Users can also leave their email addresses to receive the Vfold3D results through email.

Vfold3D may predict multiple all-atom 3D structures if multiple optimal templates are available in the database.

An error message will be given, if Vfold3D cannot find proper templates for at least one motif.

On the result page, Vfold3D outputs the predicted all-atom 3D structure(s) in the PDB format (see Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

An example of the Vfold3D prediction. (a) Input interface of Vfold3D server. Users have options to input sequence, and 2D structure in dot-bracket format. (b) Output interface of Vfold3D server. Users can download predicted 3D structures from the result page. An error message will be displayed if Vfold3D cannot find proper templates for at least one motif. (c) The comparison between the predicted and native structures (RMSD = 6.9 Å).

We use yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitch as an example to show how Vfold predicts 3D structures. The Vfold2D predicted 2D structure shows seven helices, one four-way junction, three internal/bulge loops, three hairpin loops, and one 5′-unpaired loop. For the 2D structure from Vfold2D, which contains incorrectly predicted 5 (out of 33) canonical base pairs, the RMSD to the experimentally determined native structure is 6.9 Å (Fig. 4c), indicates that Vfold3D predicted structure can indeed capture the global fold of the structure, even for 2D structures with minor inaccuracies.

If the (fully correct) native 2D structure (see Note 16) of the yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitch is used as the input for Vfold3D, the RMSD of the predicted 3D structure would be reduced to 3.3 Å. The usage of the A-form helices in Vfold3D, which is slightly different from the helices in the experimentally determined RNA structures, may cause a notable contribution to the RMSD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01-GM063732.

Footnotes

A survey of the known structures suggests that the virtual bonds (P-C4′ and C4′-P) have bond length of ~3.9 Å and bond angle in the range of 90° – 120°.

By enumerating all the possible (sequence-dependent) intra-loop mismatches considered in the Vfold2D algorithm, the Vfold model can partially account for the sequence-dependence of the loop free energy.

The usage of all-atom helices can better account for the exclude volume effects between helices and between helices and loops in the loop entropy calculations.

The length of each loop is limited to 8 nt for the complete loop virtual-bonded structure ensemble, due to the long computational time for the exhaustive self-avoiding walks.

For the RNA 3D structures solved by NMR, only the first model is used to extract motifs for the database.

An RMSD cutoff of 1.2 Å (between the standard A-form helix and the helices in real RNA structures) is used for the helix extraction.

The fragment assembly-based method only considers the intra-loop structural features. While the motif assembly-based method conserves both the intra- and inter loop interactions within the motifs.

Each helix should contain at least 2 base pairs. The helices with single base pair are treated as the intra-motif interactions.

Vfold defines the sequence distance H = Σ i hi to find the optimal templates. Here, hi is the hamming distance between nucleotide i in the selected template and the corresponding nucleotide in the target sequence through the following substitution cycles: A→G→C→U, C→U→A→G, G→A→U→C, U→C→G→A.

The MD minimization, such as AMBER and NAMD, only causes small RMSD change in 3D structure. Currently, the energy minimization has not been automated in the Vfold3D server.

We have pre-tabulated Vfold-derived parameters for the different types of the loops (25, 29, 30, 31, 32).

There are minor differences between these two sets of energy parameters.

The computational time scales with the chain length N as O(N6) and the memory scales as O(N2).

RNAs often have multiple, heterogeneous conformational distributions with the formation of multiple stable and metastable structures. Therefore, the predicted minimum free energy structures may not always correspond to the native structures, due to the conformational flexibility and the uncertainty in the energy parameters derived by the experiments and theories.

The sequence of yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitch is: 5′AAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGGAAACCGAAACAAAG UCGUCAAUUCGUGAGGAAACUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACGAAAGUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCU UUCC3′.

The native 2D structure: (((((......((.((((....))))((((((((((.......(((((....)))))))))))))))(((((((....)))))))..))....)))))..

References

- 1.Ladd M, Palmer R. Structure determination by X-ray crystallography. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furtig B, Richter C, Wohnert J, Schwalbe H. NMR spectroscopy of RNA. Chembiochem. 2003;4(10):936–962. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender W, Davidson N. Mapping of poly (A) sequences in the electron microscope reveals unusual structure of type C oncornavirus RNA molecules. Cell. 1976;7(4):595–607. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proudfoot NJ, Brownlee GG. 3 non-coding region sequences in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 1976;2(12):211–214. doi: 10.1038/263211a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner PP, Giegerich R. A comprehensive comparison of comparative RNA structure prediction approaches. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews DH, Moss WN, Turner DH. Folding and finding RNA secondary structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003665. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washietl S. Sequence and structure analysis of noncoding RNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;609:285–306. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-241-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado-Lima A, del Portillo HA, Durham AM. Computational methods in noncoding RNA research. J Math Biol. 2008;56:15–49. doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathews DH, Turner DH. Prediction of RNA secondary structure by free energy minimization. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato K, Kato Y, Akutsu T, Asai K, Sakakibara Y. DAFS: simultaneous aligning and folding of RNA sequences via dual decomposition. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(24):3218–3224. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews DH, Turner DH. Dynalign: an algorithm for finding the secondary structure common to two RNA sequences. J Mol Biol. 2002;317(2):191–203. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker BJ, Breaker RR. Riboswitches as versatile gene control elements. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15(3):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellaousov S, Reuter JS, Seetin MG, Methews DH. RNAstructure: web servers for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W471–W474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofacker IL. Vienna RNA secondary structure server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3429–3431. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner DH, Mathews DH. NNDB: the nearest neighbor parameter database for predicting stability of nucleic acid secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D280–D282. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan RK, Petrov AS, Harvey SC. YUP: A Molecular Simulation Program for Coarse-Grained and Multi-Scaled Models. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:529–540. doi: 10.1021/ct050323r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonikas MA, Radmer RJ, Laederach A, Das R, Pearlman S, Herschlag D, Altman RB. Coarse-grained modeling of large RNA molecules with knowledge-based potentials and structural filters. RNA. 2009;15:189–199. doi: 10.1261/rna.1270809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma S, Ding F, Dokholyan NV. iFoldRNA: three-dimensional RNA structure prediction and folding. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1951–1952. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Z, Bell DR, Shi Y, Ren P. RNA 3D structure prediction by using a coarse-grained model and experimental data. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:3135–3144. doi: 10.1021/jp400751w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das R, Karanicolas J, Baker D. Atomic accuracy in predicting and designing noncanonical RNAstructure. Nat Methods. 2010;7:291–294. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parisien M, Major F. The MC-Fold and MC-Sym pipeline infers RNA structure from sequence data. Nature. 2008;452:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao S, Chen S-J. Physics-based de novo prediction of RNA 3D structures. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:4216–4226. doi: 10.1021/jp112059y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X, Zhao P, Chen S-J. Vfold: a web server for RNA structure and folding thermodynamics prediction. PloS one. 2014;9(9):e107504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao S, Chen S-J. Predicting RNA folding thermodynamics with a reduced chain representation model. RNA. 2005;11:1884–1897. doi: 10.1261/rna.2109105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S-J. RNA folding: conformational statistics, folding kinetics, and ion electrostatics. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:197–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferro DR, Hermans J. A different best rigid-body molecular fit routine. Acta Crystallogr A. 1971;33:345–347. doi: 10.1107/S0567739477000862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnott S, Hukins DW, Dover SD. Optimised parameters for RNA double-helices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;48:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(72)90867-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao S, Chen S-J. Predicting RNA psuedoknot folding thermodynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2634–2652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao S, Chen S-J. Predicting structures and stabilities for H-type pseudoknots with inter-helix loop. RNA. 2009;15:696–706. doi: 10.1261/rna.1429009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao S, Chen S-J. Structure and stability of RNA/RNA kissing complex: with application to HIV dimerization initiation signal. RNA. 2011;17:2130–2143. doi: 10.1261/rna.026658.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao S, Chen S-J. A domain-based model for predicting large and complex pseudoknotted structures. RNA Biol. 2012;9:200–211. doi: 10.4161/rna.18488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarver M, Zirbel CL, Stombaugh J, Mokdad A, Leontis NB. FR3D: finding local and composite recurrent structural motifs in RNA 3D structures. J Math Biol. 2008;56(1–2):215–252. doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bindewald E, Hayes R, Yingling YG, Kasprzak W, Shapiro BA. RNAJunction: a database of RNA junctions and kissing loops for three-dimensional structural analysis and nanodesign. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D392–D397. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popenda M, Szachniuk M, Blazewicz M, Wasik S, Burke EK, Blazewicz J, Adamiak RW. RNA FRABASE 2.0: an advanced web-accessible database with the capacity to search the three-dimensional fragments within RNA structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrov AI, Zirbel CL, Leontis NB. Automated classification of RNA 3D motifs and the RNA 3D Motif Atlas. RNA. 2013;19(10):1327–1340. doi: 10.1261/rna.039438.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darty K, Denise A, Ponty Y. VARNA: Interactive drawing and editing of the RNA secondary structure. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1974–1975. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price IR, Gaballa A, Ding F, Helmann JD, Ke A. Mn(2+)-sensing mechanisms of yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitches. Mol Cell. 2015;57(6):1110–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]