Abstract

Background

Immunotherapy has changed the therapeutic landscape in oncology. Advanced uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) remains an incurable disease in most cases, and despite new drug approvals, improvements in overall survival have been modest at best. The goal of this study was to evaluate programmed-death 1 (PD-1) inhibition with nivolumab in this patient population

Methods

This single-center phase 2 trial completed enrollment between May and October 2015. Patients received 3 mg/kg of intravenous nivolumab on day 1 of each 2-week cycle until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary endpoint was objective response rate. We assessed PD-1, PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and PD-L2 expression in archival tumor samples and variations in immune-phenotyping of circulating immune cells during treatment

Results

Twelve patients were enrolled in the first stage of the 2-stage design. A median of 5 (range, 2-6) 2-week cycles of nivolumab were administered. Of the 12 patients, none responded to treatment. The overall median progression-free survival was 1.8 months (95% confidence interval, 0.8-unknown). The study did not open the second stage due to lack of benefit as defined by the statistical plan. Archival samples were available for 83% of patients. PD-1 (>3% of cells), PD-L1, and PD-L2 (>5% and >10% of tumor cells, respectively) expression were observed in 20%, 20%, and 90% of samples, respectively. No significant differences were observed between pre- and posttreatment cell phenotypes.

Conclusion

Single-agent nivolumab did not demonstrate a benefit in this cohort of previously treated advanced ULMS patients. Further biomarker-driven approaches and studies evaluating combined immune checkpoint-modulators should be considered.

Keywords: uterine leiomyosarcoma, immunotherapy, nivolumab, anti, programmed-death 1 (PD-1), sarcoma

Introduction

Uterine sarcomas account for nearly 3% of all uterine malignancies, of which uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS), a malignant tumor of smooth muscle lineage differentiation, constitutes the most common subtype with an annual incidence of 0.64 per 100,000 women.1-3 Treatment for early stage localized ULMS is usually surgical, however, ULMS is characterized by a high propensity for hematogenous spread and high recurrence rates, with local and distant failures of 45%-80%.4-6 Systemic treatments for advanced ULMS with doxorubicin- or gemcitabine-based regimens typically demonstrate a median progression-free survival (PFS) period of 6-8 months and a median overall survival (OS) of fewer than 2 years.7-9 Even the most recently approved drugs for sarcoma subtypes (including ULMS), pazopanib and trabectedin, have not shown an OS benefit in clinical trials, thus a search for effective systemic treatments for ULMS is ongoing.10,11

Although the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in sarcoma has not been established, immunotherapy has shown potential activity in a specific sarcoma subtype, synovial sarcoma, and an association between tumor immune infiltration and outcome in leiomyosarcoma has been observed.12-14 Infiltration of programmed-death 1 (PD-1)–positive lymphocytes and programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive tumor cells in soft tissue sarcoma has been associated with poor clinical outcomes.15 Moreover, ULMS is associated with infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). TAMs exert a suppressive tumor microenvironment through L-arginine depletion (by arginase-1) and production of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide radicals; this in turn induces down-regulation of T cell receptor and cell cycle arrest, resulting in suppression of T cell function and T cell anergy.16,17 High numbers of TAMs also correlate with tumor progression and metastases and have been associated with poor prognosis in gynecological leiomyosarcoma. 12,13

Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody, selectively blocks the PD-1 receptor, interrupting the interaction with PD-L1 and PD-L2, expressed both on tumor cells and immune cells.18 Disruption of the PD-1 and PD-L1 axis has been shown to restore antitumor immunity and enhance clinical activity resulting in superior survival outcome in metastatic melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.18-20. Because of the potential relevance of immune regulation in ULMS, the current study was performed to evaluate immune checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab in patients with advanced ULMS.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Treatment

This single-center, 2-stage phase 2 trial of nivolumab was conducted among patients with histologically confirmed advanced ULMS—defined as metastatic or unresectable ULMS—who received at least 1 prior line of chemotherapy, either in the adjuvant or metastatic setting. Patients were 18 years of age or older, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≤1, had at least one measurable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1), and had normal organ and marrow function.21 Patient ineligibility included prior treatment with an anti–PD-1, anti–PD-L1, anti–PD-L2, anti–cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) antibody, or other antibody or drug specifically targeting T cell costimulation or immune checkpoint pathways, active autoimmune disease, active brain metastasis or leptomeningeal disease, or required systemic glucocorticoid-replacement therapy (>10 mg daily prednisone equivalents) or other immunosuppressive medications within 14 days of study drug administration. All patients received 3 mg/kg of nivolumab every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Cycle length was defined as 2 weeks.

Study Design

This 2-stage trial was designed to assess the objective response among patients with advanced ULMS treated with nivolumab using the exact binomial distribution. With a null hypothesis of 5% and an alternative hypothesis of 20%, 12 patients were required in the first stage and 25 patients were required in the second stage. At least one response among 12 patients was needed to continue onto the second stage. The overall power was 90%, the overall type 1 error was 9%, and the probability of stopping at the first stage under the null hypothesis was 54%.

Outcomes

The primary objective of this trial was objective tumor response rate, defined as complete or partial response per RECIST 1.1 criteria.21 Disease assessment was planned to be performed every 12 weeks. In addition to the planned disease assessment, additional disease assessments could be performed at the investigators' discretion in the event of clinical decline as would be consistent with standard of care. Secondary objectives included investigator-assessed PFS—defined as the duration of time from start of treatment to time of objective disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first—and evaluation of nivolumab toxicity assessed per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 4.0.

Correlative Biomarkers

We explored the relationship between objective response rate and PFS to specific markers of immunomodulation including PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 expression (see Supporting Information) in archival tumor material, and whenever possible, in prestudy (ie, before the first dose of nivolumab) and on-treatment (ie, between weeks 4 and 6) biopsies. The percentage of the tumor cells staining positive for PD-L1 and PD-L2 and the intensity of the tumor cells were recorded as 0 (no staining), +1 (weak staining), +2 (moderate staining) and +3 (intense staining). Absolute PD-1–positive cells were counted under a microscope at ×20 power field. PD-1 positivity was defined if >3% positive cells/high power field, and PD-L1/PD-L2 were considered positive if >5% and 10% of tumor cell population demonstrated unequivocally staining (+1, +2, or +3 intensity), respectively. We hypothesized that PD-1, PD-L1, and PD-L2 expression, either alone or in combination, may identify a subset of patients with ULMS who are more likely to respond to nivolumab.

We also prospectively monitored peripheral blood for changes in immune function using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from whole blood samples drawn before each dose of nivolumab for the first 12 weeks and at off-study. Surface staining with a panel of antibodies (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, FoxP3, CD11c, CD83, CD86, CD56), followed by flow cytometry, were performed to identify T regulatory cells, natural killer and natural killer T cells, T cell activation and checkpoint markers, and memory T cells. Data from pre- and post-treatment cryopreserved PBMCs were analyzed to identify cell populations specified above as percent of the parent population (see Supporting Information).22

Statistical Analysis

All enrolled patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug were eligible for efficacy and toxicity analyses. Two-sided 95% exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for objective response. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For outcomes other than response, a 2-sided P < .05 defined statistical significance. STATA version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between May and October 2015, 12 patients were enrolled and received at least 1 dose of nivolumab. The median age at registration was 54.5 years (range, 29-73 years). All patients had received at least 1 prior chemotherapy regimen with a median of 4 prior therapies (range, 1-10). Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics (n = 12).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 11 (92) |

| African American | 1 (8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 11 (92) |

| Hispanic | 1 (8) |

| Age at registration, y, median (range) | 54.5 (29-73) |

| Age at diagnosis, y, median (range) | 51 (26-68) |

| Performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 9 (75) |

| 1 | 3 (24) |

| Prior treatment lines,a n (%) | |

| 1 | 4 (33) |

| 2 | 2 (17) |

| ≥3 | 6 (50) |

| Prior pelvic radiation, n (%) | 4 (33) |

| Total number of cycles received on study | |

| 1 | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 3 (25) |

| 3 | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 2 (17) |

| 5 | 1 (8) |

| 6 | 6 (50) |

| Reason off study drug, n (%) | |

| Disease progression on drug | 9 (75) |

| Investigator's choice | 2 (17) |

| Adverse events/side effects | 1 (8) |

All patients received a gemcitabine-based regimen before study enrollment; 75% of patients also received a doxorubicin-based regimen.

Treatment and Response

Nivolumab was administered in 2-week cycles, with median of 5 cycles (range, 2-6 cycles). Five patients experienced RECIST 1.1–defined disease progression during cycles 2-4 (weeks 2-8). A total of 9 patients were removed from the study due to progressive disease per RECIST 1.1. One additional patient experienced clinical progression that was not confirmed radiographically, and 2 patients were removed for investigator/patient choice. Objective responses were seen in 0 of 12 patients. At least 1 response was required to continue onto the second stage; therefore, the trial was closed at the completion of the first stage.

PFS and OS

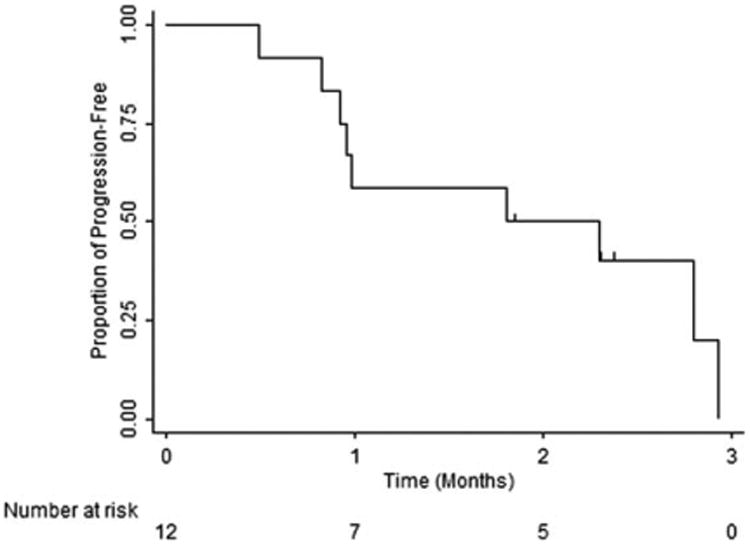

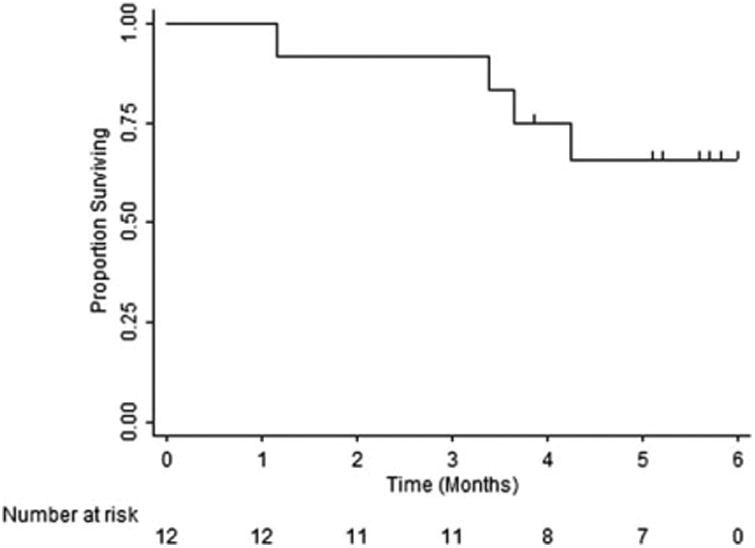

Survival analysis included all patients. The overall median PFS was 1.8 months (95% confidence interval, 0.8-unknown) (Fig. 1). Because of the small number of patients in the cohort and limited follow-up, the median OS was not met (Fig. 2); however, 4 of the 12 patients died during the 100-day study follow-up period. All deaths were due to disease progression.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival.

Figure 2.

Overall survival.

Correlative Studies

Archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples were available for correlative studies in 10 of the 12 patients. Immunohistochemistry staining of archival tumor samples was positive (>3% cells) for PD-1 expression in 2 samples, PD-L1 expression (>5% tumor cells) in 2 samples (one positive also for PD-1), and PD-L2 (>10% tumor cells) in 9 of the 10 samples. An on-treatment sample (after cycle 3) was available for 1 patient and showed inflammation that was not present in the patient's archival tumor; however, both tumor samples were negative for PD-1 expression. Staining for PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression demonstrated increased positivity in the on-treatment sample from 10% to 20% and 20% to 50%, respectively. This patient received a total of 6 cycles (12 weeks) of nivolumab before disease progression.

Pretreatment and 5-8 weeks posttreatment immune-phenotyping of PBMCs by flow cytometry was performed for all patients and compared using a paired t test. There were no significant differences between any of the pre-and posttreatment cell phenotypes or T cell activation/ checkpoint markers (eg, CD3+CD8+PDL1+, CD3+CD8+ICOS+).

Adverse Events

Nine patients experienced a grade 3 or higher toxicity of any relationship to study drug. Three patients experienced toxicity at least possibly related to study drug, which included grade 3 abdominal pain, grade 4 serum amylase and lipase increase, and grade 3 fatigue. Details are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Grade 3 or Higher Toxicities.

| Patient | Toxicity | Grade | Relationship to Drug |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dyspnea | 3 | Unrelated |

| 1 | Dyspnea | 5 | Unrelated |

| 2 | Small intestinal obstruction | 3 | Unrelated |

| 3 | Hematuria | 3 | Unrelated |

| 3 | Depression | 4 | Unrelated |

| 4 | Abdominal pain | 3 | Possible |

| 6 | Renal colic | 3 | Unrelated |

| 9 | Serum amylase increased | 4 | Definite |

| 9 | Lipase increased | 4 | Definite |

| 10 | Dyspnea | 3 | Unrelated |

| 10 | Cardiac arrest | 5 | Unrelated |

| 11 | Fatigue | 3 | Probable |

| 12 | Cough | 3 | Unrelated |

| 12 | Dyspnea | 3 | Unrelated |

Discussion

Current systemic treatment options for patients with metastatic ULMS include gemcitabine- or anthracycline-based chemotherapy, the multikinase inhibitor pazopanib, and trabectedin. As of today, each of these regimens offer a median PFS of several months; however, a consistent benefit in OS has not yet been demonstrated. Anti–PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition has shown unprecedented clinical activity and durable responses across a variety of solid tumors, including previously considered “low-immunogenic” tumors such as non–small cell lung cancer and bladder carcinoma.20,23

This phase 2 trial did not show clinical activity for nivolumab among patients with ULMS in terms of objective response or progression-free survival. The lack of response with nivolumab observed in our cohort of patients correlates with results from the SARC028 phase 2 study, which evaluated PD-1 blockade using the anti PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in patients with advanced soft tissue and bone sarcomas. The soft tissue arm comprised four subtypes (leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, and synovial sarcoma), and the overall response rate was 17.5% observed among patients with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (4/10), liposarcoma (2/10), and synovial sarcoma (1/10), whereas no response was observed among the leiomyosarcoma cohort (0/10).24 ULMS is a disease of complex cytogenetic and molecular aberrancies; genome-wide array-based comparative genomic hybridization show chromosomal aberrations with specific regions of high level gain and loss, thus the underlying determinants driving this disease continue to be elucidated.25 Furthermore, little is known about tumor antigens which drive effective anti-tumor response in CD8 T cells activated by checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. During the last decade, next generation sequencing has provided considerable data on the landscape of somatic mutations in human tumors and their remarkable high frequencies. It has been shown that peptides encoded by some of these mutated genes, after being processed and presented on cell surface major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, can elicit T cell immunoreactivity, although these antigens remain almost completely undefined.26 Hopefully, a more comprehensive recognition of these immunogenic mutations in specific cancer types, including ULMS, would allow for better patient selection and outcome in response to anti–PD-1 therapy.

This study has several limitations. In addition to the small cohort of patients, immunohistochemistry staining was performed on archival tumor tissues, which may not represent the current tumor immune status at the time of study enrollment. Expression of PD-L1 is known to be inducible and dynamic and is regulated by extrinsic signaling, such as release of interferon-γ by tumor-infiltrating immune cells, and intrinsic cellular control, such as loss of tumor suppressor PTEN or activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, all of which are implicated in ULMS.27,28 Furthermore, PD-L1 expression was not a prerequisite eligibility criterion in our trial, resulting in an 80% negative PD-L1 expression in evaluable archival tumors. Although the debate is ongoing as to the use of PD-L1 as a biomarker for treatment response, higher expression levels of PD-L1 have correlated with higher response rates in other solid tumors, such as melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer.19,29 We also observed low staining of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes infiltrate in tumor samples which is in concordance with the low PD-L1 expression, and may further explain the lack of response to anti–PD-1 therapy in this study.30-32

Nevertheless, dysfunctional antitumor T cells may be kept unresponsive by more than one repressor, thus a combination of 2 immune checkpoint inhibitors may enhance the antitumor activity of each individual treatment.33 Indeed, combination therapy with nivolumab and another immune checkpoint inhibitor, ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 antibody, has demonstrated superior efficacy over nivolumab or ipilimumab monotherapy in melanoma where subgroup analysis suggested a greater benefit with combination therapy in the context of PD-L1–negative tumors, where a prolongation of PFS of more than double was noted for the combination arm versus nivolumab mono-therapy in PD-L1 negative tumors.34,35 Furthermore, a case of an exceptional response to pembrolizumab in a patient with metastatic ULMS has been reported, tumor regression at multiple metastatic sites occurred within a relatively short period of time (2 months) and complete pathologic response at responsive tumor sites was observed at time of surgery.36 Although far from being representative, it shows a potential benefit for PD-1/PD-L1 axis inhibition in ULMS, and should encourage further exploration of predictive biomarkers for response to immune checkpoint modulators in ULMS.

In conclusion, single-agent nivolumab did not demonstrate benefit in this cohort of previously treated patients with advanced ULMS. Due to the interesting association of TAMs and ULMS, investigation of additional novel combinations of immunotherapy in this disease should be considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This study was supported by core grant P30 CA006516 from the National Cancer Institute and the Catherine England Leiomyosarcoma Research Fund. Geoffrey I. Shapiro has received an NIH UM1 CA186709 grant.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Scott J. Rodig has received grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb. F. Stephen Hodi holds patent-pending royalties regarding a patent on MICA-related disorders; is a consultant for Merck, Novartis, and EMD Serono; has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has received personal fees from Merck, Genentech, Novartis, and EMD Serono. Andrew J. Wagner has received personal fees from Eli Lilly. Suzanne George has received research support from Pfizer, Novartis, Blueprint Medicines, Deciphera, and ARIAD.

Footnotes

Clinical trial number: NCT02428192.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Author Contributions: Eytan Ben-Ami: Investigation, data curation, writing, visualization. Constance M. Barysauskas: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing. Sarah Solomon, Kadija Tahlil, Rita Malley: Investigation, project administration. Melissa Hohos, Kathleen Polson, Margaret Loucks: Investigation. Mariano Severgnini, Tara Patel, Amy Cunningham, Scott J. Rodig: Investigation, resources, data curation. F. Stephen Hodi: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation. Jeffrey A. Morgan, Priscilla Merriam, Andrew J. Wagner: Investigation. Geoffrey I. Shapiro: Investigation, funding acquisition. Suzanne George: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing, Visualization, supervision, funding acquisition.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zivanovic O, Leitao M, Lasonos A, Lindsay M, Jacks Q, Abu Rustum N. Stage-specific outcomes of patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma: a comparison of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Systems. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2066–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Echt G, Jepson J, Steel J, et al. Treatment of uterine sarcomas. Cancer. 1990;66:35–39. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<35::aid-cncr2820660108>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadducci A, Landoni F, Sartori E, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:25–32. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salazar OM, Bonfiglio TA, Patten SF, et al. Uterine sarcomas: natural history, treatment and prognosis. Cancer. 1978;42:1152–1160. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3<1152::aid-cncr2820420319>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinh TA, Oliva EA, Fuller AF, Jr, et al. The treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Results from a 10-year experience (1990-1999) at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raut CP, Nucci MR, Wang Q, et al. Predictive value of FIGO and AJCC staging systems in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2818–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensley ML, Blessing JA, Mannel R, et al. Fixed-dose rate gemcitabine plus docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic uterine leiomyosarcoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group phase II trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muss HB, Bundy B, DiSaia PJ, et al. Treatment of recurrent or advanced uterine sarcoma. A randomized trial of doxorubicin versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (a phase III trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group) Cancer. 1985;55:1648–1653. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850415)55:8<1648::aid-cncr2820550806>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. PALETTE study group Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of conventional chemotherapy: results of a phase III randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:786–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganjoo KN, Witten D, Patel M, et al. The prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophages in leiomyosarcoma: a single institution study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34:82–86. doi: 10.1097/coc.0b013e3181d26d5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinosa I, Beck AH, Lee CH, et al. Coordinate expression of colony-stimulating factor-1 and colony-stimulating factor-1-related proteins is associated with poor prognosis in gynecological leiomyosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2347–2356. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JR, Moon YJ, Kwon KS, et al. Tumor infiltrating PD1-positive lymphocytes and the expression of PD-L1 predict poor prognosis of soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Ochoa AC. L-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2007;109:1568–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human cancer. Cancer J. 2010;16:348–353. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eb3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauera EA, Therasseb P, Bogaertsc J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reimann KA, Chernoff M, Wilkening CL, et al. Preservation of lymphocyte immunophenotype and proliferative responses in cryo-preserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immuno-deficiency virus type 1-infected donors: implications for multicenter clinical trials. The ACTG Immunology Advanced Technology Laboratories. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:352–359. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.3.352-359.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine DG, et al. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515:558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tawbi HA, Burgess MA, Crowley J, et al. Safety and efficacy of PD-1 blockade using pembrolizumab in patients with advanced soft tissue (STS) and bone sarcomas (BS): results of SARC028—a multicenter phase II study [abstract 11006] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):11006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho YL, Bae S, Koo MS, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization analysis of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson J, Gustafsson K, Himoudi N. Licensing of killer dendritic ceels in mouse and humans: functional similarities between IKDC and human blood gd T-lymphocytes. J Immunotoxicol. 2012;9:259–266. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2012.685528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song M, Chen D, Lu B, et al. PTEN loss increases PD-L1 protein expression and affects the correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical parameters in colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lastwika KJ, Wilson W, 3rd, Li QK, et al. Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:227–238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gandini S, Massi D, Mandala M. PD-L1 expression in cancer patients receiving anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;100:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5064–5074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santarpia M, Karachaliou N. Tumor immune microenvironment characterization and response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:74–78. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao D, Adeegbe D, Rodig SJ, et al. Response and oligoclonal resistance to pembrolizumab in uterine leiomyosarcoma: genomic, neo-antigen, and immunohistochemical evaluation [abstract 11043] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):11043. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.