Abstract

A sensitive method based on high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) has been developed for the simultaneous determination of folic acid (FA) and its active metabolite, 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid (5-M-THF), in human plasma. The analytes were extracted from plasma with methanol solution containing 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.025% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide. FA and 5-M-THF were more stable after the addition of 2-mercaptoethanol and ammonium hydroxide in the sample preparation procedures of this study than they were in the previously published methods. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Hedera ODS-2 column using a gradient elution system of acetonitrile and 1 mM ammonium acetate buffer solution containing 0.6% formic acid as mobile phase. LC–MS/MS was carried out with an ESI ion-source and operated in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The assay was linear over the concentration ranges of 0.249–19.9 ng/mL for FA, and 5.05–50.5 ng/mL for 5-M-THF. The developed LC–MS/MS method offers increased sensitivity for quantification of FA and 5-M-THF in human plasma and was applicable to a pharmacokinetic study of FA and 5-M-THF.

Keywords: Folic acid, 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid, 2-Mercaptoethanol, LC–MS/MS, Pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

Folates belong to B vitamins and are essential elements in the diet. They are a group of compounds derived from food-stuffs. The key folate forms include folic acid (FA), 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid (5-M-THF), 5-formyltetrahydrofolate, 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate, S-adenosylmethionine, and S-adenosylhomocysteine [1]. Previous studies showed that folate deficiency was associated with increased risk of neural tube defects [2], [3], coronary heart disease [4], [5], certain types of cancer [6], [7], Down's syndrome [8], and red-cell aplasia [9]. Nowadays FA is used as an oral supplement by patients with these disorders and recommended to women of childbearing age to reduce the risk of neural tube defects. FA is absorbed in the small intestine and is reduced to the metabolically active tetrahydrofolate forms inside the cells. 5-M-THF is the most predominant active metabolite, which accounts for approximately 98% of folates in human plasma [10].

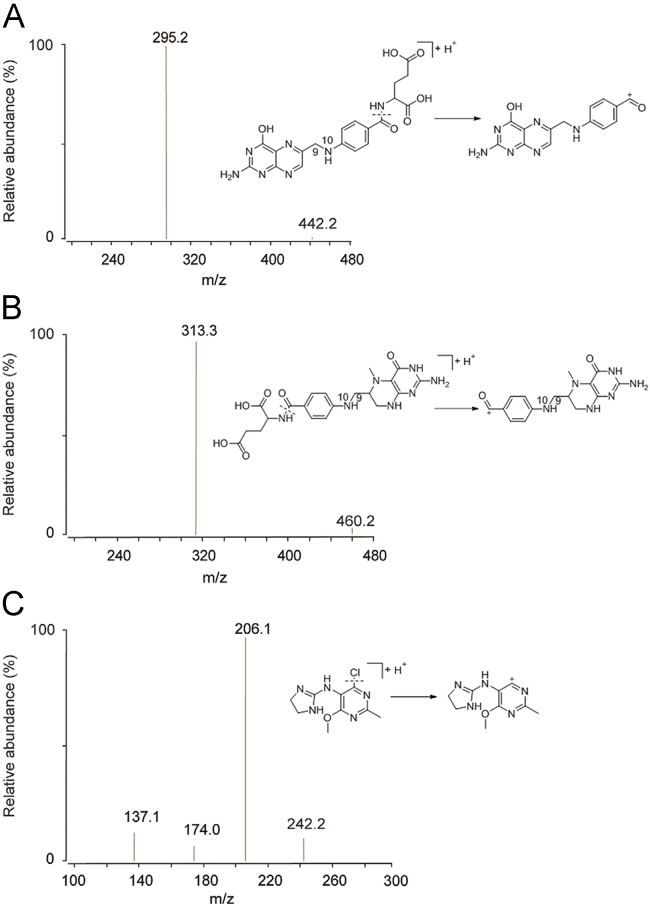

The structures of FA and 5-M-THF are shown in Fig. 1. The main challenge in FA and 5-M-THF quantification is their instability due to the cleavage of the C9–N10 covalent bond and the reduction of the pterin ring [11], because they are easily degraded under different conditions of temperature [12], pH [12], [13], oxygen [14] or light [15]. Just as early research reports, FA and 5-M-THF are more stable in alkaline conditions than in acidic conditions [16].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of (A) FA, (B) 5-M-THF and (C) IS and their proposed fragmentation patterns.

Folates in human serum and plasma have been measured by various chromatographic methods, including high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [17], liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) [18], and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) [1], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. However, these methods were not all convenient for routine analysis due to various reasons such as employing large sample volumes [19], having long retention time [21] or applying time-consuming extraction procedures (purified by folate binding protein affinity columns[19] or solid-phase extraction (SPE) [21], [22], [23], [24]). Moreover, these reports did not put emphasis on the stability of FA and 5-M-THF during the sample preparation process. This paper describes a reliable and reproducible LC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of FA and 5-M-THF in human plasma and it has been applied to the pharmacokinetic study of FA and 5-M-THF in healthy Chinese male volunteers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

The reference standard of FA (89.7%) was purchased from the National Institute for Food and Drug Control (Beijing, China), reference standard of moxonidine (99.2%) was obtained from the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, China), and reference standard of 5-M-THF (98.1%) was supplied by Toronto Research Chemical Inc. (Ontario, Canada). Acetonitrile and methanol were of gradient grade for liquid chromatography (Merck, Germany). Formic acid, ammonium hydroxide and ammonium acetate were of analytical grade purity and were purchased from Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). 2-Mercaptoethanol was purchased from Shanghai Sigma Metals, Inc. (Shanghai, China). FA tablets containing 5 mg of FA were purchased from Jiangsu Yabang Epson Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Yancheng, China) and FA tablets containing 0.4 mg of FA were purchased from Beijing Slaine Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. Instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

The liquid chromatography was performed on an Agilent 1200 Series liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), which comprised an Agilent 1200 binary pump (model G1312B), a vacuum degasser (model G1322A), an Agilent 1200 autosampler (model G1367C), and a temperature controlled column compartment (model G1330B). The chromatographic separation was carried out on a Hedera ODS-2 analytical column (150 mm×2.1 mm i.d, 5 μm; Hanbon Science and Technology, Huaian, Jiangsu, China) with a security guard C18 column (4 mm×2.0 mm i.d., 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at the temperature of 38 °C.

The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (solvent A) and 1 mM ammonium acetate buffer solution containing 0.6% formic acid (solvent B) was delivered at 0.40 mL/min according to the following programs: 0–0.8 min (89% B), 1.0–2.0 min (30% B), 2.2–5.0 min (10% B), and 5.2–10.0 min (89% B). The column effluent was directed into the mass spectrometer at the time interval of 0–4.0 min, otherwise to waste. Autosampler temperature was maintained at 4 °C and an injection volume of 8 μL was used in each run.

The LC system was coupled with an Agilent 6410B triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an electrospray source (model G1956B). The electrospray ionization source was set with a drying nitrogen gas flow of 12 L/min, nebulizer pressure of 40 psig, drying gas temperature of 350 °C, capillary voltage of 4.0 kV in positive ion mode. The fragmentor voltages for FA, 5-M-THF and IS were 90, 105 and 100 V, respectively. The fragmentation transitions for the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) were m/z 442.2→295.2 for FA with a collision energy (CE) of 22 eV, m/z 460.2→313.3 for 5-M-THF with a CE of 20 eV, and m/z 242.1→206.1 for IS with a CE of 20 eV, respectively. Chemical structures of FA, 5-M-THF and IS and their proposed fragmentation patterns are presented in Fig. 1.

2.3. Preparation of calibration standards and quality control samples

All FA and 5-M-THF standard solutions were prepared under dim light to protect them from oxidative degradation by light. Stock solutions of FA (497 μg/mL) and 5-M-THF (505 μg/mL) were prepared in methanol: 5 mM of ammonium acetate solution (50:50, v/v) containing 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol and diluted with the same solution to make a series of standard working solutions of 4.98, 9.95, 39.8, 99.5, 199, 298 and 398 ng/mL for FA and 101, 202, 303, 404, 606, 808 and 1010 ng/mL for 5-M-THF.

Seven mixed calibration standard samples were then prepared by spiking 500 μL of blank human plasma with 25 μL of working solutions to give respective final concentrations of 0.249, 0.498, 1.99, 4.98, 9.95, 14.9 and 19.9 ng/mL for FA and 5.05, 10.1, 15.2, 20.2, 30.3, 40.4 and 50.5 ng/mL for 5-M-THF. Three mixed quality control (QC) samples at three concentration levels (low: 0.595 ng/mL for FA and 12.1 ng/mL for 5-M-THF; medium: 2.98 ng/mL for FA and 21.2 ng/mL for 5-M-THF; high: 15.9 ng/mL for FA and 42.4 ng/mL for 5-M-THF) were prepared independently in the same way. The IS working solution with the concentration of 50.2 ng/mL was prepared in methanol. All standard solutions and plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

2.4. Sample preparation

To an aliquot of 500 μL of human plasma (containing 100 μg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol), 25 μL IS working solution (50.2 ng/mL) was added and mixed for 10 s. The mixture was deproteinized with 1.5 mL of methanol solution containing 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.025% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide. After vortex for 3 min and centrifuged at 2005g for 10 min, the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas in a water-bath of 35 °C to dryness. The residue was immediately reconstituted in 150 μL of acetonitrile – 5 mM of ammonium acetate buffer solution (11:89, v/v) containing 10 mg/mL 2-mercaptoethanol. After vortex for 3 min, the reconstituted solution was transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 17024 g for 10 min. An 8 μL of the supernatant was injected into the LC–MS/MS system for analysis. The whole sample preparation process was carried out under a dim light condition.

2.5. Method validation

Assay validation was performed according to FDA guidelines [25].

Selectivity was performed using six different batches of blank human plasma. Each blank sample should be tested for no other endogenous components interference at the retention time of FA and 5-M-THF except the endogenous FA and 5-M-THF and no endogenous components interference at the retention time of IS.

FA and 5-M-THF are both endogenous substances in human plasma, so their baseline levels in the blank plasma should be subtracted from the calibration plasma samples before constructing the calibration curves. We calculated the peak area ratio (f ) of FA and 5-M-THF (As) to that of the internal standard (Ai), f=As/Ai, in calibration plasma samples. The obtained peak area ratio of the blank plasma was defined as fBK. The adjusted peak area ratio of the calibration samples was defined as f’, f’=f−fBK. Calibration curves of FA and 5-M-THF were respectively constructed by plotting the f’ values against the amount added to the blank samples and were calculated using linear regression analysis with 1/x2 weighing.

Accuracy and precision were evaluated according to Ref. [26]. Five replicate QC samples at three concentration levels were analyzed on the same day and on three consecutive days in three analytical batches using calibration curves established daily. The precision at each concentration level was expressed as relative standard deviation (%RSD) and accuracy as relative error (%RE). The intra- and inter-day precision (%RSD) should not exceed 15% and the accuracy (%RE) should be within ±15%. Lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was the lowest concentration on the calibration curve that can be measured with acceptable accuracy and precision. The LLOQ was established using five samples independent of the standards and the intra- and inter-day precision (%RSD) which should not exceed 20% and the accuracy (%RE) should be within ±20%.

The extraction recovery (expressed as R) and the matrix effect (expressed as ME) of FA and 5-M-THF were determined by analyzing six replicates of QC samples at three concentration levels. R was calculated by comparing the peak areas obtained from the peak areas of extracted spiked samples (defined as A) subtracting those of the extracted blank human samples (defined as A0) with the peak areas obtained from the peak areas of analytes spiked post-extraction (defined as B) subtracting A0, R=(A−A0)/(B−A0)×100%. ME was evaluated by comparing the peak areas obtained from B subtracting A0 with the mean peak area of the neat standard solutions of the analytes (defined as C), ME=(B−A0)/C×100%. The extraction recovery and matrix effect of the IS were evaluated in the same procedure, but A0 of IS was zero.

The stability of FA and 5-M-THF in plasma containing 100 µg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol under different storage conditions was evaluated by QC samples at low and high concentration levels in three replicates, including after being kept at room temperature for 7.5 h, stored at −80 °C for 50 days, and analyzed after three freeze-thaw cycles. The supernatant stability test was conducted by reanalyzing QC samples at low and high concentration levels kept under autosampler (4 °C) for 10 h, at room temperature for 12 h and at −80 °C for 24 h.

2.6. Pharmacokinetic study

A pharmacokinetic study was performed in 20 healthy Chinese male volunteers approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Suzhou, China). The reference of the protocol is No. 2011L01475. All the volunteers were recruited after thorough medical, biochemical and physical examinations and were given written informed consent to participate in the study according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsink. During the experiment, subjects consumed an identical and specially- prepared low-folate diet boiled at least for 1 h to eliminate the folates in foods.

To minimize the inter-individual differences of FA 5-M-THF baseline levels in the volunteers, a presaturation regimen with FA was followed. The volunteers were fasted overnight (10 h) and given an FA tablet (containing 5 mg FA) at 7:00 a.m. and then ate breakfast at 8:00 a.m. for four consecutive days, followed by three FA-free days (without the treatment of FA tablet). Then, the volunteers fasted overnight (10 h) and were administered two FA tablets (0.4 mg×2) at 7:00 a.m. on the eighth day. Blood samples (4 mL) were collected into heparin tubes at 0, 0.167, 0.333, 0.667, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4 (before lunch), 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 (before supper) and 24 h after administration of drugs. Plasma was separated from the blood by centrifugation at 2005g at 4 °C for 5 min. Aliquot of 50 µL of 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol was added to each milliliter separated plasma sample immediately and vortex-mixed for 10 s. Plasma samples were frozen at −80 °C until analysis. There is no circadian variation in folate baseline in human; thus the baseline concentration was only assessed by the plasma sample collected before drug administration. The baseline concentrations of the analytes should be subtracted when calculating their pharmacokinetic parameters.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Stability studies

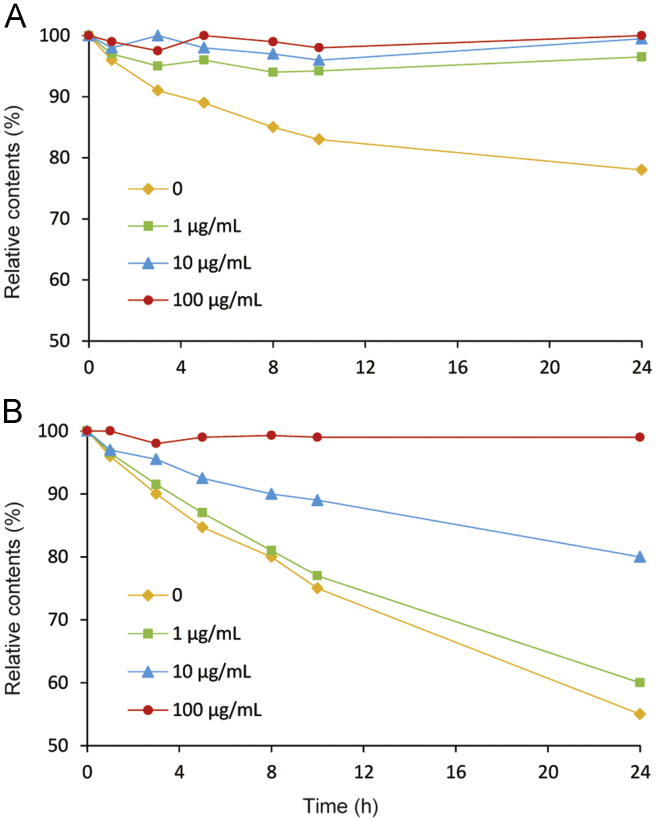

Folates are known to be degradable compounds that are sensitive to heat, pH, oxygen and light. For unstable analytes, the greatest challenge is how to keep them stable before and during analysis [27]. De Brouwer et al. [13] reported that FA and 5-M-THF were relatively stable at different pH values (from 2 to 10) with and without heat treatment in phosphate buffer containing 1% ascorbic acid and 2% 2-mercaptoethanol. Kirsch [23] found that FA and 5-M-THF were stable at 4 °C over 24 h in aqueous solutions with or without ascorbic acid at different pH values. Nevertheless, the composition of the plasma was more complex than aqueous solutions. In our study, the stability of FA and 5-M-THF in plasma was investigated at room temperature (about 20 °C) over 24 h without or with 2-mercaptoethanol at three concentration levels (1, 10 and 100 μg/mL). It was clearly observed that FA and 5-M-THF in plasma degraded faster without 2-mercaptoethanol than with 2-mercaptoethanol, and FA was stable in plasma with 1 μg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 2A), but 5-M-THF was not stable until the concentration of 2-mercaptoethanol in plasma was increased to 100 μg/mL (Fig. 2B). According to our investigation and in accordance with previous study [18], FA and 5-M-THF degraded in acidic conditions but stayed stable in neutral and basic conditions at room temperature. Moreover, it was also found that 5-M-THF degraded fast in dried residue at room temperature because of the absence of 2-mercaptoethanol. Thus several disposal methods such as adding 2-mercaptoethanol as a single antioxidant; keeping at a non-acid condition as well as avoiding light should be taken into consideration to avoid the degradation of FA and 5-M-THF during all the sample preparation period. As a result, we optimized the precipitant (methanol) and the reconstitution fluid (acetonitrile: 5 mM ammonium acetate, 11:89, v/v) by adding 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.025% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide. At the same time, the sample preparation was carried out under dim light. All these disposal methods guaranteed the stability of FA and 5-M-THF during pretreatment and ensured the accurate quantitation of them to some extent.

Fig. 2.

The degradation of (A) FA (9.95 ng/mL) and (B) 5-M-THF (20.2 ng/mL) in plasma at different concentration levels of 2-mercaptoethanol at room temperature.

3.2. Method development

Most of the reported procedures [21], [22], [23], [24] have applied SPE (using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges or ion exchange and mixed mode solid-phase extraction cartridges) for plasma extraction for the analysis of FA. Instead of SPE, our sample preparation required methanol precipitation followed by drying. 2-Mercaptoethanol was used as an antioxidant added into the plasma sample prior to the sample preparation and it was also added into methanol and reconstitution fluid in the preparation procedure. The specific measures were: (i) after the plasma was separated from the blood, aliquot of 50 µL of 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol was added to each milliliter separated plasma sample immediately; (ii) the methanol solution and the reconstituted fluid both contained 10 mg/mL of 2-mercaptoethanol so that the post-preparation samples contained 2-mercaptoethanol. This relative simple and rapid sample handling procedure met the sensitivity requirement with minimal degradation of the highly unstable folates. As for the MS condition, detection with the positive ionization mode was found to produce a better response than that with the negative ionization mode. As for the chromatographic condition, acetonitrile was preferred to methanol as it gave a better peak shape. At the same time, the addition of 0.6% formic acid in the aqueous portion of the mobile phase produced more symmetrical peaks and much higher mass spectrometric response for FA and 5-M-THF. Meanwhile, 1 mM of ammonium acetate was added into the aqueous portion of the mobile phase, too. The buffer solution containing 0.6% formic acid and 1 mM of ammonium acetate helped to stabilize the mobile phase pH and improve the peak shapes of the analytes. In order to eliminate the matrix effect, a gradient elution system was performed and each chromatographic run was completed within 10.0 min.

3.3. Assay validation

3.3.1. Selectivity

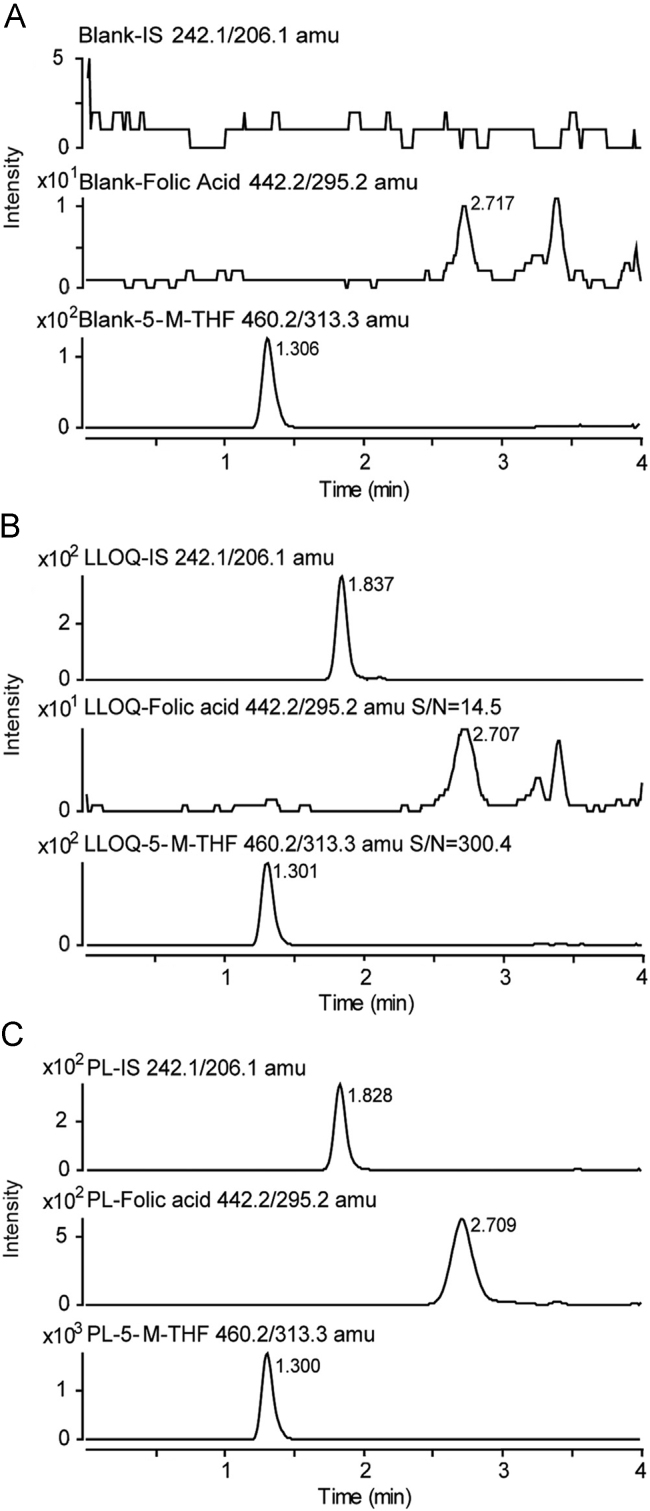

Fig. 3 shows the typical chromatograms of blank plasma, LLOQ for FA and 5-M-THF, and the plasma sample from a volunteer after an oral administration. The retention time of FA, 5-M-THF and the IS was 2.71, 1.30 and 1.83 min, respectively. No significant interference in the blank plasma samples was observed at the retention time of the IS.

Fig. 3.

Typical chromatograms of (A) blank plasma; (B) LLOQ for FA (0.249 ng/mL), 5-M-THF (5.05 ng/mL) and IS in plasma; and (C) plasma obtained from a volunteer at 1.5 h after an oral administration of 0.8 mg folic acid.

3.3.2. Calibration curve

Calibration curves were linear over the concentration ranges of 0.249–19.9 ng/mL for FA with correlation coefficient r≥0.999, and 5.05–50.5 ng/mL for 5-M-THF with correlation coefficient r≥0.996. The typical equations of the calibration curves were: f’=0.179C+0.00869 for FA and f’=0.0925C+0.0139 for 5-M-THF.

3.3.3. Accuracy and precision

Table 1 summarizes the precision and accuracy for the analysis of FA and 5-M-THF in human plasma (n=15) evaluated by assaying the LLOQ and QC samples.

Table 1.

Precision and accuracy for the analytes in human plasma (n=20, 5 replicates per day for 3 days).

| Analyte | Nominal concentration (ng/mL) | Intra-day |

Inter-day |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured concentration (ng/mL) | Precision (%RSD) | Accuracy (%RE) | Measured concentration (ng/mL) | Precision (%RSD) | Accuracy (%RE) | ||

| FA | 0.249 | 0.266 ±0.019 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 0.266±0.019 | 3.8 | 7.0 |

| 0.595 | 0.639±0.025 | 5.0 | 7.3 | 0.627±0.033 | 6.6 | 5.3 | |

| 2.98 | 2.95±0.17 | 6.8 | −0.9 | 3.01±0.19 | 4.5 | 1.0 | |

| 15.9 | 16.0±0.7 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 16.2±0.8 | 8.8 | 1.8 | |

| 5-M-THF | 5.05 | 4.64±0.56 | 9.4 | −8.1 | 4.95±0.56 | 8.8 | −1.9 |

| 12.1 | 13.1±0.2 | 3.1 | 8.1 | 13.2±0.43 | 4.0 | 8.9 | |

| 21.2 | 22.8±0.7 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 22.7±0.8 | 3.1 | 6.9 | |

| 42.4 | 46.2±0.9 | 2.9 | 8.9 | 45.5±1.9 | 8.4 | 7.2 | |

RSD: relative standard deviation.

RE: relative error.

3.3.4. Extraction recovery and matrix effects

The extraction recovery and matrix effect results of the analytes are shown in Table 2. These data indicated that the sample preparation method was proved to be successful and the coeluting matrix components had no appreciable matrix effect on the analytes.

Table 2.

Extraction recovery and matrix effects for the analytes in human plasma (n=6).

| Analyte | Spiked concentration (ng/mL) | Extraction recovery |

Matrix effect |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | RSD (%) | Mean (%) | RSD (%) | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 89.2 | 5.9 | 94.0 | 2.6 |

| 2.98 | 87.0 | 7.0 | 97.2 | 5.8 | |

| 15.9 | 88.4 | 2.7 | 108.7 | 4.1 | |

| 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 88.8 | 2.9 | 100.6 | 5.0 |

| 21.2 | 91.1 | 3.1 | 100.9 | 4.8 | |

| 42.4 | 89.3 | 2.6 | 101.6 | 4.9 | |

| IS | 2.51 | 83.4 | 3.9 | 102.9 | 4.5 |

3.3.5. Stability

The stability of FA and 5-M-THF in plasma was studied under a variety of storage conditions. The results are shown in Table 3. FA and 5-M-THF were proved to be stable under the test conditions.

Table 3.

Stability of FA and 5-M-THF in plasma under different storage conditions (n=3).

| Storage conditions | Analytes | Concentration levels (ng/mL) |

RSD (%) | RE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Determined | ||||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.580 | 4.7 | −2.6 | |

| Residue stability | 15.9 | 16.5 | 1.4 | 3.9 | |

| (1 h, room temperature) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 13.2 | 1.4 | 8.8 |

| 42.4 | 46.3 | 1.1 | 9.1 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.637 | 6.2 | 7.1 | |

| Short-term stability | 15.9 | 16.7 | 3.2 | 5.3 | |

| (7.5 h, room temperature) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 12.4 | 0.6 | 2.1 |

| 42.4 | 44.2 | 1.3 | 4.3 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.587 | 6.4 | −1.4 | |

| Freeze/thaw stability | 15.9 | 14.8 | 0.5 | −7.2 | |

| (three cycles) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 12.8 | 4.5 | 5.2 |

| 42.4 | 46.0 | 5.0 | 8.3 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.658 | 6.8 | 10.6 | |

| Long-term stability | 15.9 | 16.9 | 4.1 | 6.3 | |

| (50 days, −80 °C) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 10.8 | 2.6 | −10.8 |

| 42.4 | 41.2 | 4.6 | −2.9 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.617 | 6.7 | 3.8 | |

| Autosampler stability | 15.9 | 17.2 | 2.9 | 8.1 | |

| (10 h, 4 °C) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 12.3 | 7.8 | 1.5 |

| 42.4 | 43.1 | 0.8 | 1.6 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.566 | 6.1 | −4.9 | |

| Supernatant stability | 15.9 | 16.6 | 7.9 | 4.5 | |

| (12 h, room temperature) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 13.0 | 1.9 | 7.6 |

| 42.4 | 46.4 | 3.5 | 9.4 | ||

| FA | 0.595 | 0.580 | 3.5 | −2.6 | |

| Supernatant stability | 15.9 | 14.8 | 4.2 | −2.0 | |

| (24 h, −80 °C) | 5-M-THF | 12.1 | 12.3 | 6.4 | 1.2 |

| 42.4 | 44.8 | 3.0 | 5.6 | ||

3.4. Pharmacokinetics study

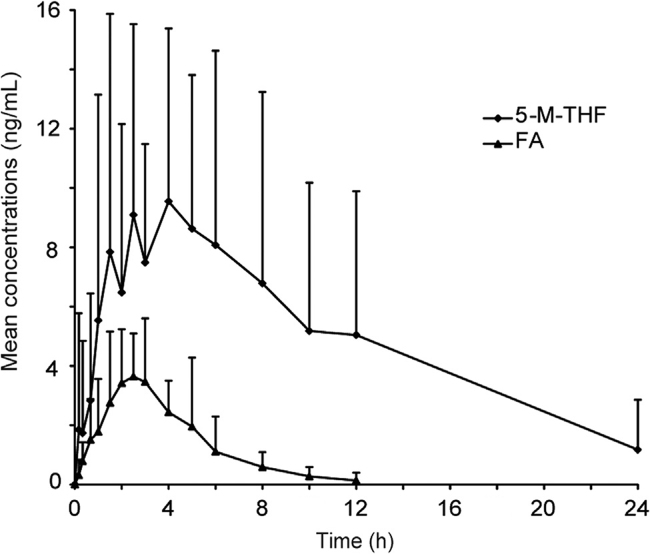

This validated LC–MS/MS method was successfully applied to a pharmacokinetic study of FA and 5-M-THF in 20 healthy Chinese male volunteers after an oral administration of 0.8 mg of FA. The mean plasma concentrations–time profiles of FA and 5-M-THF are presented in Fig. 4 and the pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Mean plasma concentration-time profiles (mean±SD, baseline values corrected) of FA and 5-M-THF in human plasma after an oral administration of 0.8 mg ofb folic acid (n=20).

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of FA and 5-M-THF (mean±SD) in 20 healthy Chinese male volunteers after an oral administration of 0.8 mg folic acid.

| Parameters | FA | 5-M-THF |

|---|---|---|

| AUC0−t (ng/mL h) | 14.6±6.6 | 121.4±62.5 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 5.38±2.14 | 15.7±8.0 |

| Tmax (h) | 2.7±1.4 | 4.4±3.5 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.4±1.5 | 5.6±7.5 |

AUC0−t: area under the plasma mean concentrations–time curve from zero to t. For FA t=12 h and for 5-M-THF t=24 h.

Cmax: peak concentration in plasma.

Tmax: time to peak concentration.

t1/2: half-life of drug elimination during the terminal phase.

4. Conclusion

A relative simple and reproducible LC–MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of FA and 5-M-THF in human plasma has been developed and validated. Instead of SPE, the method of protein precipitation has a lot of advantages, such as simplifying the sample preparation, increasing the speed of sample preparation and minimizing the degradation of FA and 5-M-THF. Meanwhile, the addition of antioxidant 2-mercaptoethanol, the non-acid condition and the immediate reconstitution during the sample preparation can effectively ensure the stability of FA and 5-M-THF. The developed method has been successfully applied to the pharmacokinetic study of FA and 5-M-THF in healthy Chinese male volunteers.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Contributor Information

Quan-Ying Zhang, Email: zqysz11@163.com.

Li Ding, Email: dinglidl@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Wang X.W., Zhang T., Zhao X. Quantification of folate metabolites in serum using ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2014;962:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control Use of folic acid for prevention of spina bifida and other neural tube defects – 1983–1991. MMVR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1991;40:513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects. Pediatrics. 1993;92:493–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison H.I., Schaubel D., Desmeurles M. Serum folate and risk of fatal coronary heart disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1996;275:1893–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530480035037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giles W.H., Kittner S.J., Croft J.B. Serum folate and risk for coronary heart disease: results from a cohort of US adults. Ann. Epidemiol. 1998;8:490–496. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirachainan N., Wongruangsri S., Kajanachumpol S. Folate pathway genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility of central nervous system tumors in Thai children. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2008;32:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine A.J., Figueiredo J.C., Lee W. A candidate gene study of folate-associated one carbon metabolism genes and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010;19:1812–1821. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biselli J.M., Brumati D., Frigeri V.F. A80G polymorphism of reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1) and C776G polymorphism of transcobalamin 2 (TC2) genes in Down's syndrome etiology. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2008;126:329–332. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802008000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gothoni G., Vuoristo M., Kontula K. High-dose folic acid treatment for red-cell aplasia. Lancet. 1995;345:1645–1646. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pietrzik K., Bailey L., Shane B. Folic acid and l-5-methyltetrahydrofolate: comparison of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:535–548. doi: 10.2165/11532990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinlivan E.P., Hanson A.D., Gregory J.F. The analysis of folate and its metabolic precursors in biological samples. Anal. Biochem. 2006;348:163–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen M.T., Hendrickx M. Effect of pH on temperature stability of folates. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2004;69:203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Brouwer V., Zhang G.F., Storozhenko S. pH stability of individual folates during critical sample preparation steps in prevision of the analysis of plant folates. Phytochem. Anal. 2007;18:496–508. doi: 10.1002/pca.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rozoy E., Simard S., Liu Y.Z. The use of cyclic voltammetry to study the oxidation of L-5-methyltetrahydrofolate and its preservation by ascorbic acid. Food Chem. 2012;132:1429–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mastropaolo W., Wilson M.A. Effect of light on serum B12 and folate stability. Clin. Chem. 1993;39:913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arcot J., Shrestha A. Folate: methods of analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005;16:253–266. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman S.K., Greene B.C., Streiff R.R. A study of serum folate by high performance ion-exchange and ion-pair partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1978;145:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart D.J., Finglas P.M., Wolfe C.A. Determination of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (13C-labeled and unlabeled) in human plasma and urine by combined liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2002;305:206–213. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kok R.M., Smith D.E., Dainty J.R. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid and folic acid measured in plasma with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: applications to folate absorption and metabolism. Anal. Biochem. 2004;326:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannisdal R., Ueland P.M., Svardal A. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis of folate and folate catabolites in human serum. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:1147–1154. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez Sanchez B., Priego Capote F., Mata Granados J. Automated determination of folate catabolites in human biofluids (urine, breast milk and serum) by on-line SPE-HILIC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010;1217:4688–4695. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazili Z., Whitehead R.D., Paladugula N. A high-throughput LC–MS/MS method suitable for population biomonitoring measures five serum folate vitamers and one oxidation product. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013;405:4549–4560. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6854-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirsch S.H., Knapp J.P., Herrmann W. Quantification of key folate forms in serum using stable-isotope dilution ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2010;878:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rychlik M., Netzel M., Pfannebecker I. Application of stable isotope dilution assays based on liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for the assessment of folate bioavailability. J. Chromatogr. B. 2003;792:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DHHS US, CDER FDA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center For Veterinary Medicine (CV); 2013. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation. Available at: 〈http://www/fda.gov/cder/guidance/index.htm〉. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang P., Sun J.B., Gao E.Z. Simultaneous determination of limonin, dictamnine, obacunone and fraxinellone in rat plasma by a validated UHPLC–MS/MS and its application to a pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of Cortex Dictamni extract. J. Chromatogr. B. 2013;928:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi X., Ding L., Wen A. Simple LC–MS/MS methods for simultaneous determination of pitavastatin and its lactone metabolite in human plasma and urine involving a procedure for inhibiting the conversion of pitavastatin lactone to pitavastatin in plasma and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013;72:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]