Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to measure and compare the apparent transverse relaxation time constants (T2) of five intracellular metabolites using LASER and PRESS sequences in the human brain at 3 T.

Methods

Five healthy subjects were studied at 3 T. 1H spectra from the prefrontal cortex were acquired at six different echo-times using LASER and PRESS sequences. Post-processed data were analyzed with LCModel and the resulting amplitudes were fitted using a mono-exponential decay function to determine the T2 of metabolites.

Results

21% higher apparent T2s for the singlet resonances of N-acetyl aspartate, total creatine, and total choline were measured with LASER as compared to PRESS while comparable apparent T2s were measured for strongly-coupled metabolites, glutamate and myo-inositol, with both sequences.

Conclusion

Reliable T2 measurements were obtained with both sequences for the five major intracellular metabolites. The LASER sequence seems to be more efficient in suppressing the diffusion component for singlets (having non-exchangeable protons) compared to J-coupled metabolites.

Keywords: 3 T, brain, LASER, PRESS, T2 relaxation time constants

Introduction

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) is a non-invasive technique that allows the measurement of multiple metabolites in the brain in vivo at the same time. These MR visible metabolites are primarily located in the intracellular compartments. The most commonly measured brain metabolites at relatively short echo time (TE) are N-acetyl aspartate (NAA), total creatine (tCr, creatine plus phosphocreatine), choline containing compounds (tCho, phosphorylcholine plus glycerophosphorylcholine), glutamate (Glu), and myo-inositol (mIns). These metabolites are preferentially concentrated in certain cell types. For instance, NAA and Glu are predominantly located in neurons, tCr and tCho are found in both neuronal and glial cells, and mIns is thought to be localized exclusively in astrocytes (1). By measuring the transverse relaxation time constants (T2), which are sensitive to changes in the molecular motion mainly through interaction of metabolites with structural or cystolic macromolecules (2), the cellular microenvironment of these metabolites can be probed.

Two spin echo pulse sequences commonly used in MRS studies are LASER (Localization by Adiabatic SElective Refocusing) (3) and PRESS (Point RESolved Spectroscopy) (4). Both sequences provide full-intensity signal. However, on clinical 3 T and above systems, PRESS suffers from larger chemical shift displacement (CSD) error (> 10%/ppm) due to the limited bandwidth of its refocusing pulses than the LASER sequence, which uses broad bandwidth adiabatic full-passage (AFP) refocusing pulses.

Many studies have reported the apparent T2 relaxation time constants of singlet resonances, e.g., NAA, tCr and tCho in the human brain from 1.5 T to 7 T using PRESS and LASER sequences (2,5–10). However, so far fewer human studies have measured the T2 of J-coupled metabolites such as Glu and mIns using those techniques (5–8,11). Interestingly, it was previously demonstrated that the apparent T2 of NAA, tCr, and water were lengthened with the CP-LASER sequence, a variant of LASER with an additional Carr-Purcell pulse train (12), compared to PRESS in the human brain at 4 and 7 T (13).

There have not been any studies comparing the T2 values for intracellular metabolites measured with LASER and PRESS. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to measure and compare the apparent T2 relaxation times of five major metabolites using LASER and PRESS sequences in the human brain on a clinical 3 T scanner. High SNR spectra were acquired over a large TE range with both sequences such that there was no bias in estimating the T2 relaxation of metabolites.

Methods

Five healthy subjects (21 ± 1 years old, 4 males) were studied on a 3 T whole-body Siemens Prismafit scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) after giving informed consent to participate in the study approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. The standard body coil was used for excitation while the 32-channel receive-only Siemens head coil was used for signal reception. A volume-of-interest (VOI) of 25×25×25 mm3 was positioned in the prefrontal cortex (anterior to the genu of corpus callosum and centered on the interhemispheric fissure) using 3D T1-weighted MPRAGE images (0.8 mm3 isotropic resolution, repetition time, TR = 2400 ms, TE = 2.24 ms, inversion time, TI = 1060 ms, flip angle = 8°, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2). B0 shimming inside the VOI was achieved using the system 3D GRE shim, operated in the “brain” shim mode. The VOIs contained 64 ± 6 % of gray matter, 24 ± 7 % of white matter, and 12 ± 3 % of cerebrospinal fluid.

Localized 1H spectra were acquired in one session using both LASER and PRESS sequences with VAPOR water suppression (14). In PRESS, OVS pulses were interleaved within VAPOR to eliminate signals from outside of the VOI generated by the localization pulses. B1 field for the 90° and the water suppression flip angle were calibrated in the VOI. All data for both pulse sequences were obtained with a TR of 3 s, a spectral width of 6 kHz and with 2048 complex points. Signals for all coil elements were combined on the scanner using the phase and weighting information obtained from the coil sensitivities of the water reference scan (15) to generate a free induction decay (FID). Each FID was individually saved as a DICOM file for further post-processing offline.

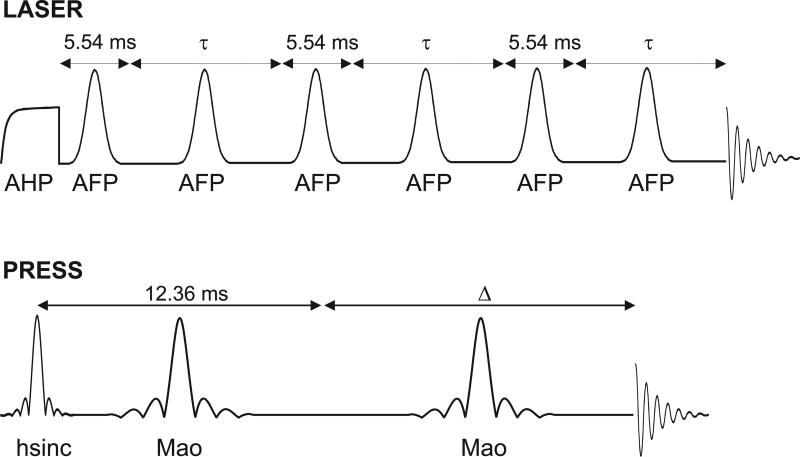

The LASER sequence consisted of a 5.12 ms adiabatic half-passage (AHP) pulse (16), which was used to nonselectively excite all resonances, followed by 3D localization performed using a pair of AFP pulses (GOIA-HS4 modulation (17), 3.22 ms duration, 15.52 kHz bandwidth, CSD of 0.8%/ppm) in each dimension. To achieve 3D localization, the PRESS sequence used a 2.6 ms hsinc pulse (3.42 kHz bandwidth, CSD of 3.6%/ppm) for excitation and two 5.2 ms Mao pulses (1.11 kHz bandwidth, CSD of 11.1%/ppm) for refocusing.

The TE in LASER was defined as the delay from the end of the AHP pulse to the start of signal acquisition since the AHP pulse places the magnetization in the transverse plane at the end of the pulse (16). The TE was unevenly distributed (Figure 1) with as short as possible delay surrounding the first AFP pulse (i.e., 5.54 ms). Identical delays of 5.54 ms were used around the 3rd and 5th AFP pulses. For the T2 measurements, the delays around the 2nd, 4th, and 6th AFP pulses were varied equally. Metabolite LASER spectra were collected at six different TEs: 35, 140, 230, 290, 330, and 400 ms, with 8, 16, 32, 32, 64, and 128 averages, respectively. Non-suppressed water spectra were acquired at the same TEs for eddy current correction and for the determination of the apparent T2 of tissue water. The TE in PRESS was defined as the delay from the middle of the excitation pulse to the start of signal acquisition (Figure 1). The delay between the excitation and the first refocusing pulse was fixed at 12.36 ms (the shortest timing possible), while the delay around the second refocusing pulse was varied. Metabolite PRESS spectra were collected at six different TEs: 23, 60, 140, 210, 270, and 400 ms, with 4, 16, 32, 32, 64, and 128 averages, respectively. Water reference scans were also acquired at the same TEs. These TEs were chosen preferentially for measurement of T2 of Glu and mIns based on simulations. The total acquisition time to measure the whole TE series for each sequence was ~16 min.

Figure 1.

RF pulse diagrams for LASER and PRESS sequences used for T2 measurements. In LASER, the delay between the AHP pulse and around the first AFP pulse was kept as short as possible, i.e., 5.54 ms, while the τ delay was varied to change the TE which is given by (5.54 + τ)*3. Similarly in PRESS, the first delay between the excitation and first refocusing pulse was fixed at the shortest delay of 12.36 ms while the delay △ around the second refocusing pulse was varied and the TE is defined as (12.36 + △). For simplicity, the localization and spoiler gradients used in both sequences are not shown.

All metabolite spectra, i.e. individually FIDs saved in DICOM format, were processed in Matlab (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) in the following way: first, eddy current effects were corrected using the water reference scans, followed by single-shot frequency correction based on a cross-correlation algorithm, and phase correction using a least-square algorithm before summation. Resulting spectra were averaged and then analyzed with LCModel version 6.3-0G (Stephen Provencher Inc., Ontario, Canada) (18) without applying any baseline correction, zero-filling, or apodization functions to the in vivo data, and the spectra were fitted over the 0.5 to 4.2 ppm range.

Basis sets at the different TEs used in the study were simulated in Matlab using density matrix formalism based on measured and published chemical shift and J-coupling values (19–21). To account for the large CSD error in PRESS, 2D localized simulation (40×40 spatial points (22)) was performed along the direction of the refocusing pulses while taking into account all RF shapes and timings used in vivo. For PRESS, localization was achieved by frequency sweeping the refocusing pulses from BWb + 0 ppm to BWb + 4.5 ppm where BWb is the bandwidth of the pulse at the base (23). For LASER, non-localized simulation with actual RF shapes and timings was sufficient due to minimal CSD error. The basis set at all TEs contained the following 19 metabolites: alanine, ascorbate, aspartate, creatine, γ-aminobutyric acid, glucose, Glu, glutamine, glutathione, glycerophosphorylcholine, mIns, scyllo-inositol, lactate, NAA, N-acetylaspartylglutamate, phosphocreatine, phosphorylcholine, phosphorylethanolamine, and taurine. Separate basis spectra were generated for the CH3 and CH2 groups of creatine and phosphocreatine, and for the singlet and multiplet (i.e., CH3 and CH2 groups) resonances of NAA (denoted as sNAA and mNAA, respectively) (7). In addition, measured macromolecule spectra (TR/TI = 2500/740 ms, 128 averages) were included in the basis set at 35 ms in LASER and at 23, 60, and 140 ms in PRESS, while for all other TEs macromolecules were not considered due to their negligible contribution.

The apparent T2 relaxation time constants of metabolites with Cramér-Rao Lower bounds (CRLB) < 25% were obtained by fitting the amplitudes (S) obtained from LCModel analysis with a mono-exponential decay function (i.e., , where So is the signal area at TE = 0 ms) based on the nonlinear least square algorithm in Matlab.

Water reference spectra were eddy current corrected before the water peak was integrated in Matlab. To obtain the T2 of tissue water, resulting amplitudes (Sw) were fitted using a single-exponential function with three parametric variables, i.e., , where S1 is the baseline signal offset.

Results

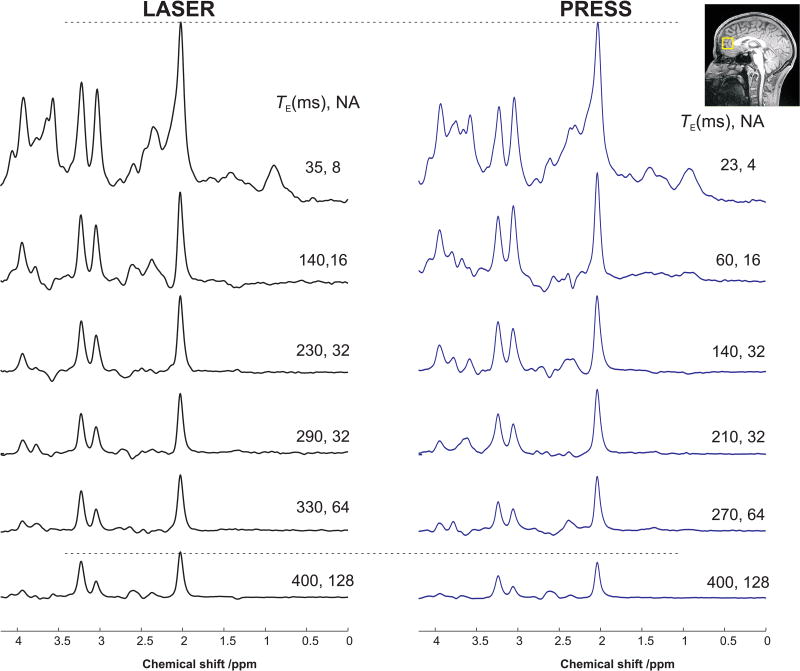

1H spectra acquired in one session from one subject at six different TEs with LASER and PRESS sequences are shown in Figure 2. Similar spectral patterns were observed for both sequences at the shortest possible TE with minimal baseline distortion from residual water and lipid contaminations. The non-uniform sampling scheme with more averages measured at longer TE resulted in high SNR spectra (> 60) at all TEs, where SNR was measured in the frequency domain and defined as peak height of NAA divided by root mean square noise.

Figure 2.

Spectra (TR = 3 s with different averages, NA) acquired at six echo times with LASER and PRESS sequences from the human prefrontal lobe at 3 T. For display purposes, the spectra were normalized such that at the shortest TE, the height of NAA peak was identical for spectra acquired with LASER and PRESS sequences. The horizontal dotted line is a visual guide to indicate that the intensity of NAA signal decreases faster in PRESS than in LASER, leading to a longer apparent T2 measured with LASER compared to PRESS. The VOI location in the prefrontal cortex is shown on the T1-weighted image.

The mean CRLBs obtained from LCModel were ≤ 4% for sNAA, tCr-CH3, and tCho with LASER and PRESS at all TEs, while CRLBs for tCr-CH2 and mNAA were < 9%. The mean CRLBs for Glu and mIns were < 12% except at 330 ms in LASER where the CRLB for mIns was 26%. At this TE, the J-evolution caused the signal integral for mIns to be almost zero, and this point was not used in the T2 fit for this metabolite.

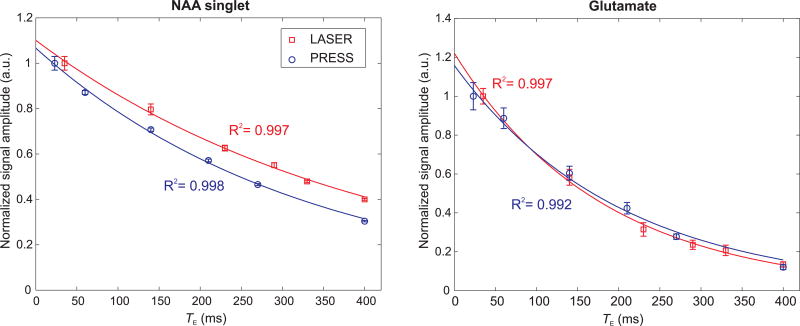

The noticeable difference in the peak heights of sNAA, tCr, and tCho visible at long TEs (Figure 2) suggests that the apparent T2s of these singlets are different between the two sequences. Indeed, the T2 relaxation times of these non-coupled resonances were found to be statistically different (P < 0.05) between LASER and PRESS (Table 1). For instance, the apparent T2 of sNAA was 369 ± 24 ms with LASER and 298 ± 20 ms with PRESS as shown in Figure 3. The T2 of the methyl group of tCr was longer than its methylene group, although their ratios were different between the two sequences. T2 of tCho was also significantly longer with LASER (387 ± 40 ms) compared to PRESS (319 ± 20 ms). tCho had the longest T2 amongst the five major metabolites measured in this study, and this could be related to the high gray matter content in the VOI (> 60%) as previously observed (8).

Table 1.

Measured T2 values (mean ± SD) from 5 subjects using LASER and PRESS sequences at 3 T with the corresponding two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. Mean goodness-of-fit (R2) was > 0.96 for all compounds except for mNAA which was 0.88 with PRESS. Statistically significant difference in T2 between the two sequences, i.e. P <0.05, are shown in bold.

| Compounds | Group | LASER T2 (ms) |

PRESS T2 (ms) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAA singlet | 2CH3 | 369 ± 24 | 298 ± 20 | <0.01 |

| tCr singlet at 3.0 ppm | N(CH3) | 195 ± 6 | 175 ± 8 | <0.01 |

| tCr singlet at 3.9 ppm | 2CH2 | 161 ± 6 | 128 ± 8 | <0.01 |

| tCho | Entire molecule | 387 ± 40 | 319 ± 20 | 0.04 |

| Glu | Entire molecule | 170 ± 10 | 191 ± 23 | 0.10 |

| mIns | Entire molecule | 194 ± 11 | 239 ± 27 | 0.06 |

| NAA multiplet | 3CH2 | 229 ± 16 | 287 ± 91 | 0.21 |

| Water | 79.0 ± 0.5 | 77.5 ± 1.2 | 0.01 |

Figure 3.

Mono-exponential fits represented by solid lines for NAA singlet and Glu from one subject as measured with LASER and PRESS sequences. The amplitude of the first TE point for each sequence was normalized to unity and error bars represent the CRLB from LCModel. The apparent T2 of sNAA was shorter with PRESS due to rapid signal decay, while for Glu it was similar for both sequences.

No statistical differences in the apparent T2 values were observed for Glu, mIns, and mNAA between LASER and PRESS (Table 1), although the standard deviations were at least 2 times higher with PRESS.

The apparent T2 of tissue water was significantly longer with LASER (79.0 ± 0.5 ms) compared to PRESS (77.5 ± 1.2 ms).

Discussion

The current study shows that the apparent T2 relaxation times of the five major metabolites, i.e. NAA, tCr, tCho, Glu and mIns, can be successfully measured in a reasonable timeframe using both LASER and PRESS sequences. Using a large range of TEs in both sequences resulted in high goodness of fit for T2 measurements without biasing the reported T2 values (24).

The apparent T2 values for singlet resonances were on average 21% higher with LASER in this study. A previous human study reported a T2 increase of nearly 75% for sNAA and tCr-CH3 with CP-LASER compared to PRESS at 4 T (13). In the current study, however, the increase in T2 was smaller between LASER and PRESS, suggesting that the apparent T2 will be further lengthened when moving from LASER to CP-LASER as demonstrated in the rat brain (25). This increase in apparent T2 under LASER could be explained by the fact that the three pairs of AFP pulses partially suppress the diffusion component, since these moieties do not have exchangeable protons in addition to having small apparent diffusion coefficients. For further suppression of the diffusion terms for non-coupled metabolites, sequences such as T2ρ-LASER (25) could be utilized, however due to SAR limitations they might not be feasible in the human brain.

By simulating the J-modulation of coupled metabolites at each TE, the apparent T2 values of Glu, mIns, and mNAA were successfully measured. The T2 of Glu was slightly lower than the T2 of mIns with both sequences, consistent with previous studies at various field strengths (6–8). The apparent T2 for the NAA CH2 group was about 60% lower than the T2 of NAA singlet with LASER while with PRESS the T2 difference between the NAA moieties was negligible (Table 1). These measured T2 values agreed with previously published values at 3 T using PRESS (6,11,26) where the T2 ranged from 180 to 284 ms. No lengthening of the apparent T2s for coupled metabolites were observed with LASER in this study. One possible explanation is that the duration of three pairs of AFP pulses in LASER is too short to refocus cross-correlation effects between different dipole-dipole interactions. It is expected that filling out the delays with additional CP pulses, as in CP-LASER and T2ρ-LASER sequences (13,25), would substantially lengthen the apparent T2 for J-coupled metabolites as previously demonstrated in animals (25).

The apparent T2 of tissue water was significantly longer by ~2% with LASER compared to PRESS. The lengthening of the T2 relaxation times of water, sNAA, and tCr-CH3 under a CP regime was previously reported in the human brain at 4 and 7 T using both MRI (27) and MRS (13) sequences, and these increases were found to be dependent on the B0 field strength. Based on these findings, an almost negligible T2 increase would be expected for water tissue at 3 T, which is consistent with the results in this study. This tiny increase in water T2 compared to singlet resonances could be explained by the high diffusivity of water compared to metabolites.

The longer apparent T2 observed for singlets with LASER in the current study might be beneficial, in terms of SNR per unit time, for studies where changes in the intracellular environment are being investigated. For instance, during normal brain aging, the apparent T2 of NAA, tCr, and tCho were shorter in elderly subjects than in young subjects (28). Similar results were observed between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia patients and control subjects (2). Another advantage of utilizing LASER over PRESS is the well-defined VOI localization with sharp and clean profiles due to use of the AFP pulses such that no additional OVS pulses are necessary (3).

Conclusion

In summary, reliable measurements of the apparent T2 relaxation times of the five major metabolites (NAA, tCr, tCho, Glu and mIns) in the human brain at 3 T were made with both LASER and PRESS sequences. The high quality and SNR of the acquired spectra allowed for improved quantification precision for these metabolites (CRLB < 15%). The T2 constants were successfully measured in a reasonable timeframe and are in good agreement with literature values. Moreover, the T2 relaxation times of singlets were lengthened by 21% on average under LASER compared to PRESS, while no differences in apparent T2 values were observed for J-coupled metabolites between the sequences. In conclusion, LASER seems to be more efficient in suppressing the diffusion component of non-coupled singlets (having non-exchangeable protons) compared to J-coupled metabolites. This property of LASER might be beneficial when probing the microcellular environment of metabolites in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants: R21AG045606, P41 EB015894, P30 NS076408.

References

- 1.de Graaf RA. In Vivo NMR Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Öngür D, Prescot AP, Jensen JE, Rouse ED, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF, Olson DP. T2 relaxation time abnormalities in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garwood M, DelaBarre L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J Magn Reson. 2001;153(2):155–177. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottomley PA. Spatial Localization in NMR Spectroscopy in Vivo. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1987;508(1):333–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb32915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soher BJ, Pattany PM, Matson GB, Maudsley AA. Observation of coupled 1H metabolite resonances at long TE. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(6):1283–1287. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganji SK, Banerjee A, Patel AM, Zhao YD, Dimitrov IE, Browning JD, Sherwood Brown E, Maher EA, Choi C. T2 measurement of J-coupled metabolites in the human brain at 3T. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(4):523–529. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deelchand DK, Henry P-G, Ugurbil K, Marjanska M. Measurement of transverse relaxation times of J-coupled metabolites in the human visual cortex at 4 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(4):891–897. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marjańska M, Auerbach EJ, Valabregue R, Van de Moortele P-F, Adriany G, Garwood M. Localized 1H NMR spectroscopy in different regions of human brain in vivo at 7T: T2 relaxation times and concentrations of cerebral metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(2):332–339. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posse S, Cuenod CA, Risinger R, Le Bihan D, Balaban RS. Anomalous transverse relaxation in 1H spectroscopy in human brain at 4 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33(2):246–252. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mlynarik V, Gruber S, Moser E. Proton T1 and T2 relaxation times of human brain metabolites at 3 Tesla. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(5):325–331. doi: 10.1002/nbm.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi C, Coupland NJ, Bhardwaj PP, Kalra S, Casault CA, Reid K, Allen PS. T2 measurement and quantification of glutamate in human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(5):971–977. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr HY, Purcell EM. Effects of Diffusion on Free Precession in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Experiments. Phys Rev. 1954;94(3):630–638. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaeli S, Garwood M, Zhu XH, DelaBarre L, Andersen P, Adriany G, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Proton T2 relaxation study of water, N-acetylaspartate, and creatine in human brain using Hahn and Carr-Purcell spin echoes at 4T and 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(4):629–633. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tkáč I, Starcuk Z, Choi IY, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1 ms echo time. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(4):649–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<649::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deelchand DK, Adanyeguh IM, Emir UE, Nguyen T-M, Valabregue R, Henry P-G, Mochel F, Öz G. Two-site reproducibility of cerebellar and brainstem neurochemical profiles with short-echo, single-voxel MRS at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(5):1718–1725. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garwood M, Ke Y. Symmetric pulses to induce arbitrary flip angles with compensation for RF inhomogeneity and resonance offsets. J Magn Reson. 1991;94:511–525. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tannus A, Garwood M. Adiabatic pulses. NMR Biomed. 1997;10(8):423–434. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199712)10:8<423::aid-nbm488>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govind V, Young K, Maudsley AA. Corrigendum: Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. In: Govindaraju V, Young K, Maudsley AA, editors. NMR Biomed. Vol. 13. 2000. pp. 129–153. NMR Biomed 2015;28(7):923–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govindaraju V, Young K, Maudsley AA. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13(3):129–153. doi: 10.1002/1099-1492(200005)13:3<129::aid-nbm619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser LG, Marjanska M, Matson GB, Iltis I, Bush SD, Soher BJ, Mueller S, Young K. 1H MRS detection of glycine residue of reduced glutathione in vivo. J Magn Reson. 2010;202(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maudsley AA, Govindaraju V, Young K, Aygula ZK, Pattany PM, Soher BJ, Matson GB. Numerical simulation of PRESS localized MR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 2005;173(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser LG, Young K, Matson GB. Numerical simulations of localized high field 1H MR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 2008;195(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brief EE, Whittall KP, Li DK, MacKay AL. Proton T2 relaxation of cerebral metabolites of normal human brain over large TE range. NMR Biomed. 2005;18(1):14–18. doi: 10.1002/nbm.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deelchand DK, Henry P-G, Marjańska M. Effect of Carr-Purcell refocusing pulse trains on transverse relaxation times of metabolites in rat brain at 9.4 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schubert F, Gallinat J, Seifert F, Rinneberg H. Glutamate concentrations in human brain using single voxel proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 Tesla. Neuroimage. 2004;21(4):1762–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartha R, Michaeli S, Merkle H, Adriany G, Andersen P, Chen W, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. In vivo 1H2O T2+ measurement in the human occipital lobe at 4T and 7T by Carr-Purcell MRI: detection of microscopic susceptibility contrast. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(4):742–750. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marjańska M, Emir UE, Deelchand DK, Terpstra M. Faster Metabolite 1H Transverse Relaxation in the Elder Human Brain. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]