Abstract

Terbinafine is a new powerful antifungal agent indicated for both oral and topical treatment of mycosessince. It is highly effective in the treatment of determatomycoses. The chemical and pharmaceutical analysis of the drug requires effective analytical methods for quality control and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies. Ever since it was introduced as an effective antifungal agent, many methods have been developed and validated for its assay in pharmaceuticals and biological materials. This article reviews the various methods reported during the last 25 years.

Keywords: Terbinafine hydrochloride, Analytical methods, Pharmaceuticals, Biological materials

1. Introduction

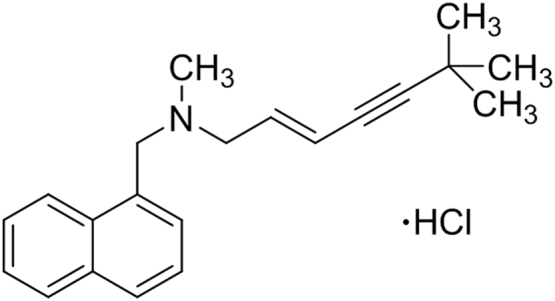

Terbinafine hydrochloride (TFH) (Fig. 1) is an allylamine derivative. Chemically, it is [(2E)-6,6-dimethylhept-2-en-4-yn-1-yl](methyl)(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)amine hydrochloride. Its molecular weight is 327.89 corresponding to the molecular formula of C21H26NCl. It melts at 195–198 °C (changes in crystal structure begin at 150 °C). TFH is freely soluble in methanol and methylene chloride; soluble in ethanol; and slightly soluble in water [1]. Like all other allylamines, it inhibits ergosterol synthesis by inhibiting squalence epoxidase an enzyme that plays a role in fungal cell wall synthesis pathway [2]. In laymans' terms, it inhibits the growth of fungal and bacterial cell wall, leading to the death of the cell, as the contents of the cell are unprotected. Therefore, it is applied to the skin in the occurrence of dermatophytoses, pityriasis versicolor and cutaneous candidiasis [3], superficial fungal infections like seborrheic dermatitis, tineacapatis, and onychomycosis especially for its short-duration therapy [4]. Generally, TFH is the main chemical form of terbinafine for pharmaceutical purposes. It comes as a tablet for oral administration, and is usually taken once a day for 6 weeks for fingernail fungus treatment and once a day for 12 weeks for toenail fungus treatment. The cream and powder formulations of the drug are used for superficial skin infections such as jock itch (tineacrusis), athlete's foot (tineapedis) and ringworm. Terbinafine is highly lipophilic in nature and tends to accumulate in skin, nails and fatty tissues. Excessive terbinafine may cause some side effects such as allergic reactions (difficulty in breathing, throat closing, and swelling of hips, tongue, face and liver), rash, and changes in vision and blood problems [5].

Fig. 1.

Terbinafine hydrochloride.

Because of its therapeutical importance, quantitative determination of terbinafine in pharmaceuticals and human physiological fluids is of considerable significance in both quality control of preparations and chemical diagnosis. In the last approximately 25 years, several methods have been reported for the determination of terbinafine in pharmaceuticals and biological materials including body fluids. The current review surveys the methods developed to determine terbinafine in drug, drug products, body fluids and other biological materials.

2. Methods for pharmaceuticals

2.1. Pharmacopoeial methods

TFH is an official drug in European Pharmacopoeia [6], British Pharmacopoeia [7] and United States Pharmacopoeia [8]. European Pharmacopoeia and British Pharmacopoeia describe a titrimetric procedure in which 250 mg of TFH is dissolved in 50 mL of 96% ethanol, 5.0 mL of 0.01 mol/L HCl is added, and the unreacted HCl is titrated with 0.1 mol/L NaOH, and the end point is determined potentiometrically. The volume of NaOH added between the two inflection points corresponds to the amount of TFH.

In the method described in United States Pharmacopoeia, TFH assay was done by using high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC), in which C18 (150 mm×3.0 mm, 5 µm) column was used as stationary phase and the mobile phase was composed of buffer (0.2% triethylamine in water, pH was adjusted to 7.5 with dilute acetic acid), acetonitrile and methanol with a gradient elution. Column temperature was set at 40 °C and the flow rate at 0.8 mL/min. Column effluent was monitored at 280 nm.

2.2. Titrimetric method

Other than the official methods [6], [7], a titrimetric method in which TFH in anhydrous acetic acid medium was titrated with 0.05 mol/L acetous perchloric acid using crystal violet indicator has been described [9]. The method was applied to bulk drug and tablets with recoveries of 100.41% and 101.81%, respectively, and a coefficient of variation of 1.64.

2.3. UV-spectrophotometric methods

In the same article [9], an UV-spectrophotometric method was described for the determination of TFH in raw materials, tablets and creams. The calibration graph was linear over the concentration range of 0.8–2.8 µg/mL (r=0.9997) with a recovery close to 100% from the formulations and a coefficient of variation of about 10. Absorbance measurement of a methanolic solution of the drug at 223 nm has facilitated its determination in a concentration range of 1–3.5 µg/mL (r2=0.999) with limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) values of 0.11 and 0.33 µg/mL, respectively. The method was applied to Fintrix coated 250 mg tablets with an accuracy of 0.08% (relative error, RE) [10]. In a similar method [11], absorbance of drug solution in methanol was measured at 282 nm and the method was applied to Tebif 250 mg tablets with an accuracy of 0.02% (RE). Beer's law was obeyed over a concentration range of 8–24 µg/mL with an LOD of 0.35 µg/mL and an LOQ of 0.81 µg/mL. Intra- and inter-day precisions were <0.5% (relative standard deviation, RSD).

Two UV-spectrophotometric methods which are stability-indicating [12] and based on the absorbance measurement of drug in 0.1 mol/L HCl at 222 nm (method A) and in 0.1 mol/L acetic acid at 282 nm (method B) were described for bulk drug and tablets. Beer's law was obeyed over the concentration ranges of 0.2–4.0 µg/mL and 2.0–50 µg/mL for method A and method B, respectively, with corresponding molar absorptivities of 8.72×104 and 7.97×103 L/mol/cm. The methods were applied to the determination of TFH in tablets with a good accuracy (RE≤1.26%) and precision (RSD≤0.32%) and without detectable interference from tablet excipients. The drug was subjected to acidic, basic, hydrolytic, oxidative, thermal and photo degradation and used to assess the stability-indicating power of the methods. In both the methods, the drug was found to undergo slight degradation under base-induced stress conditions, substantial degradation under an oxidative stress condition, and non-degradation under other stress conditions. Another UV-spectrophotometric method employing 0.1 mol/L HCl as the medium and 223 nm as the wavelength of maximum absorbance was also reported [13]. The calibration graph was linear over a concentration range of 1–3.5 µg/mL (r2=0.995), and LOD and LOQ values were 0.086 and 0.260 µg/mL, respectively. The method, when applied to coated tablets, was found to be accurate (RE<1%) and precise (RSD around 2%). Absorbance of an aqueous solution of the drug was measured at 283 nm serving as the basis of the method for TFH in bulk and tablet forms. The method was valid over the concentration range of 5–30 µg/mL with LOD and LOQ values of 0.42 and 1.30 µg/mL, respectively. The method was applied to eye drops and the results were found to be satisfactory with an RE of 0.81% and an RSD of 1.34%. The method was also demonstrated to be rugged [14].

Two UV-spectrophotometric methods developed for the quantification of TFH in the presence of its degradation products [15] make use of the first spectral derivation (1D) and the first derivative of the ratio spectra (1DD) of the drug and its photodegradates at different selected wavelengths. Good linearity was observed in the range of 10–100 mg/mL with an LOD of 1.11 mg/mL and an LOQ of 3.36 mg/mL. The methods reported show good accuracy and precision.

Simultaneous determination of TFH and triamcinolone acetonide was achieved by employing two UV-spectrophotometric methods [16]. The first method is concerned with the determination of both drugs using first derivative (D1) mode at 297 and 274 nm over the concentration ranges of 5–30 and 4–20 µg/mL, respectively. The second method depends on ratio spectra 1st derivative (RSD(1)) spectrometry at 298 and 248 nm over the same concentration ranges. The methods were applied to the determination of the drug in Limisil and Kenacort tablets and Limisil cream with a recovery of 99.35%–100.9% and an RSD of <1%. The details of UV-spectrophotometric analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance characteristics of UV-spectrophotometric methods.

| S.No. | Diluent | λmax (nm) | Linear range (µg/mL); molar extinction coefficient, Є (L/mol/cm) | LOD (µg/mL) | LOQ (µg/mL) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | 0.8–2.8 | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets, creams | [9] |

| 2 | Methanol | 223 | 1–3.5 | 0.11 | 0.33 | Tablets | [10] |

| 3 | Methanol | 282 | 8–24 | 0.35 | 0.81 | Tablets | [11] |

| 4 (a) | 0.1 mol/L HCl | 222 | 0.2–4.0; 8.72×104 | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets SIAM | [12] |

| (b) | 0.1 mol/L acetic acid | 282 | 2.0–50; 7.97×103 | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets SIAM | |

| 5 | 0.1 mol/L HCl | 223 | 1–3.5 | 0.086 | 0.26 | Tablets | [13] |

| 6 | Water | 283 | 5–30 | 0.42 | 1.3 | Bulk drug, tablets, eye drops | [14] |

| 7 | – | – | 10–100 mg/mL | 1.11 mg/mL | 3.36 mg/mL | In the presence of degradation products | [15] |

| 8 | – | 297; 298 | 5–30 | – | – | Tablets, creams | [16] |

SIAM: Stability-indicating assay method.

2.4. Visible spectrophotometric methods

Apart from UV-spectrophotometric methods, there are four reports dealing with the application of visible spectrophotometry for the assay of TFH in pharmaceuticals. TFH was reported to form an ion-pair complex with methyl orange (1:1) in buffer medium of pH 2.6, and the complex was extracted into chloroform and measured at 422 nm. This served as a basis for the assay of drug in tablets [17]. The calibration graph was linear over the range of 6–12 µg/mL TFH (r=0.9997) with a molar absorptivity of 1.89×104 L/mol/cm. The log conditional stability constant (Kf) was determined to be 5.28±0.25/mol (n=5). The method was proved to be selective against tablet excipients and applied to the determination of drug in Terbisil tablets with an RE of 0.22% and an RSD of 1.22%. Effects of nature of buffer and pH, and reagent concentration were reported and optimized. Three more extractive spectrophotometric methods [18] based on the formation of colored ion-pair complexes between TFH and molybdenum (V) thiocyanate (method A), Orange G (method B) or alizarin red S (method C) have also been described. The formed complexes were extracted with organic solvent and absorbance was measured at 470, 500 and 425 nm for methods A, B and C, respectively. The analytical parameters and their effects on the three systems were investigated. The methods permitted the determination of TFH over the concentration ranges of 5–75 µg/mL (method A), 10–80 µg/mL (method B) and 5–55 µg/mL (method C).

Three acidic triphenylmethane dyes, i.e., bromothymol blue (BTB), bromophenol blue (BPB) and bromocresol green (BCG), were reported to form chloroform-soluble ion-pair complexes with TFH in acidic medium. These reactions were used to develop three sensitive and selective visible spectrophotometric methods for the determination of the drug in formulations [19]. All the three extracted complexes showed maximum absorbance at 410 nm. The effects of dye concentration, nature of buffer and pH have been studied and optimized. Beer's law was obeyed over the concentration range of 2–25 µg/mL in all methods with a molar absorptivity value of about 2.0×105 L/mol/cm. The LOD values were 0.24, 0.28 and 0.54 µg/mL for BTB, BPB and BCG, respectively, and the respective LOQ values were evaluated to be 0.71, 0.84, and 1.62 µg/mL. The methods, when applied to Terbicip 250 mg tablets,yielded results close to 100% recovery with an RSD value of <1%. The results compared excellently with those of the reference method based on Student's t-test and variance ratio F-test. The molar ratio between TFH and the dyes was also established and found to be 1:1 in all cases. The formation constants (K) of the ion-pair complexes were in the range of 1.13×106–1.34×106/mol. Relying on different reaction schemes, drug in pure state and tablets was assayed by three simple spectrophotometric methods [20]. The first two methods are indirect and are based on the selective oxidation of the drug by chloramine T (CAT method) or permanganate (KMnO4 method) in acidic medium followed by the determination of residual oxidant by reacting with either gallocyanine and measuring the absorbance at 540 nm (CAT method) or reacting with fast green FCF and measuring the absorbance at 620 nm (KMnO4 method). The third method relies on the formation of colored charge-transfer complex with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone, in which the absorbance of the radical anion in acetonitrile was measured at 450 nm. Through charge-transfer complexation reaction with iodine [21], the drug was determined in the concentration range of 2×10−2–1×10−3 mol/L by measuring the absorbance of the complex formed in CHCl3 medium at 512 nm. The details of these methods are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance characteristics of visible-spectrophotometric and spectrofluorometric methods.

| S.No. | Reagent | Methods | Methods Linear range (µg/mL); molar extinction coefficient, Є (L/mol/cm) | LOD (µg/mL) | LOQ (µg/mL) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MO | TFH-MO ion-pair extracted into CHCl3 and measured at 422 nm. | 6–12; 1.89×104 | – | – | Tablets | [17] |

| 2 (a) | Mo(V)-SCN− | TFH-Mo(V)-SCN; TFH-OG; and TFH-ARS ion-pair complexes were extracted into organic solvents and absorbance measured at 470, 500 and 425 nm, respectively | 5–75 | – | – | Bulk drug | [18] |

| (b) | OG | 10–80 | – | – | Bulk drug | ||

| (c) | ARS | 5–55 | – | – | Bulk drug | ||

| 3 (a) | BTB | Drug-dye ion pair complexes formed in acid medium extracted into CHCl3 and measured at 410 nm | 2–25; 2.0×105 | 0.24 | 0.71 | Tablets | [19] |

| (b) | BPB | 2–25; 2.0×105 | 0.28 | 0.84 | Tablets | ||

| (c) | BCG | 2–25; 2.0×105 | 0.54 | 1.62 | Tablets | ||

| 4 (a) | CAT-GLN | Unbleached dye color measured at 540 nm | – | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets | [20] |

| (b) | KMnO4-FG FCF | Unbleached dye color measured at 620 nm. | – | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets | |

| (c) | DDQ | Charge-transfer complex formed in acetonitrile measured at 450 nm | – | – | – | Bulk drug, tablets | |

| 5 | Iodine | Drug-I2 charge-transfer complex formed in chloroform measured at 512 nm | 2×10−2–1×10−3 mol/L | – | – | – | [21] |

| 6 | Spectrofluorimetry-Water | Native fluorescence in water was measured at 376 nm after excitation at 275 nm | 0.02–0.05 | 0.0031 | 0.0094 | Tablets, cream, gel and spray, spiked human plasma | [22] |

MO: Methyl orange; Mo(V)-SCN−: Molybdenum (V) thiocyanate; OG: Orange G; ARS: Alizarin red S; BTB: Bromothymol blue; BPB: Bromophenol blue; BCG: Bromocresol green; CAT: Chloramine T; GLN: Gallocyanine; KMnO4: potassium permanganate; FG FCF: fast green FCF; DDQ: 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone.

2.5. Spectrofluorimetric method

Based on the measurement of native fluorescence of TFH in water at 376 nm after excitation at 275 nm, a rapid and highly sensitive spectrofluorimetric method has been reported for TFH in pharmaceuticals [22]. The fluorescence-concentration plot was linear over the concentration range of 0.02–0.05 µg/mL (r=0.9998) with LOD and LOQ values of 0.0031 and 0.0094 µg/mL, respectively. The method was applied to the determination of TFH in commercial tablets, cream, gel and spray formulations with an RE of <1% and an RSD of <2%. This information is also shown in Table 2.

2.6. Electrochemical methods

The electrochemical oxidation of terbinafine with boron-doped diamond (BDD) and glassy carbon (GC) electrodes was examined and applied to the determination of the drugs in pharmaceuticals [23]. The studies were performed by cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV). The supporting electrolytes, solution pH, range of potentials and the scan rates were investigated and optimized. Using BDD electrode, a linear relationship between diffusion current and concentration was obtained in the concentration ranges of 5.44×10−7–5.18×10−6 mol/L by SWV and 7.75×10−7–8.55×10−6 mol/L by DPV. For the GC electrode, linear relationship was found in the concentration ranges of 7.75×10−7–8.55×10−6 mol/L and 7.75×10−7–1.05×10−5 mol/L by SWV and DPV, respectively. The developed methods were applied to determine the drug in tablets and cream with a recovery in the range of 99.49%–101.41% and a standard deviation of 0.31%–1.89%. The effects of various reducing substances and metal ions on the voltammetric signal were also studied. PVC membrane sensor as an indicator electrode has been applied for the potentiometric assay of TFH [24]. The sensing element of the PVC membrane was made from the interaction of TFH and sodium tetraphenylborate, and the best PVC membrane was composed of 30% PVC, 62% dibutylphosphate, 6% ion-pair and 2% ionic liquid. The glass cell where terbinafine-PVC membrane was placed consisted of two Ag/AgCl double junction reference electrodes which acted as internal and external reference electrodes. The sensor demonstrated advanced performance with a fast response time, a lower detection limit of 6.65×10−6 mol/L and potential responses across the range of 7×10−6 to 1×10−2 mol/L. The sensor enabled the determination of TFH in tablets with satisfactory results (94.3%–105.4% of the labeled amounts). The selectivity coefficients of various interfering compounds were also evaluated by the matched potential method. Using manganese and zinc thiocyanate complexes, and as titrants through ion association complex formation reactions with TFH, the drug was determined in pharmaceuticals by conductometric titration [25]. The method was reported to be highly precise with an RSD of <1%. The solubility products of the resulting ion-associates were also determined. Terbinafine was found to be adsorbed on a hanging drop mercury electrode at pH 6 giving a single wave at −1.47 V vs Ag/AgCl reference electrode, due to olefinic double bond reduction. This led to the determination of the drug by voltammetry [26]. The electrochemical process was found to be irreversible and fundamentally adsorption-controlled. A systematic study of the several instrumental and accumulation variables affecting the adsorptive stripping (Ads) response was carried out using square wave voltammetry (SWV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) as redissolution techniques. The LOD values were 1.7×10−10 mol/L (Ads-SWV) and 6.3×10−7 mol/L (Ads-DPV). For the determination of the drug in Lamisil tablets and spiked human urine, a preparation step at a solid phase C18 cartridge and an Ads-SWV procedure were used and the results were precise with an RSD of <3%. Methods and performance characteristics of the electrochemical methods are compiled in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance characteristics of electrochemical methods.

| S.No. | Methods | Linear range (mol/L) | LOD (mol/L) | LOQ (mol/L) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (a) | DPV using (i)BDD electrode | (i) 7.75×10−7–8.55×10−6 | – | – | Tablets and cream | [23] |

| (ii) GC electrode | (ii)7.75×10−7–1.05×10−5 | |||||

| (b) | SWV using (iii) BDD electrode | (iii) 5.44×10−7–5.18×10−6 | – | – | ||

| (iv) GC electrode | (iv) 7.75×10−7–8.55×10−6 | |||||

| 2 | Potentiometric assay; PVC membrane sensor | 7×10−6–1×10−2 | 6.65×10−6 | – | Tablets | [24] |

| 3 | Conductometric titration; and | – | – | – | Pharmaceuticals | [25] |

| 4 (a) | Voltammetry; SWV | – | 1.7×10−10 | – | Tablets and spiked human urine | [26] |

| (b) | Voltammetry; DPV | – | 6.3×10−7 | – | Tablets and spiked human urine | |

| 5 | DPV: GC electrode | 8×10−8–5×10−5 | 2.5×10−8 | – | Human serum, clinical and pharmacokinetic studies | [46] |

DPV: Differential pulse voltammetry; SWV: Square wave voltammetry; BDD: Boron-doped diamond; GC: Glassy carbon.

2.7. Chromatographic methods

In an effort to optimize a liquid chromatographic method for quantitative analysis of terbinafine in formulations [27], the separation was carried out on an RP-C18 (250mm×4.6 mm, 5 µm) vertical column using methanol–water (95:5, v/v) as mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min with UV-detection at 254 nm. The detector response was linear over the concentration range of 20–200 μg/mL (r=0.9997) with LOD and LOQ values of 0.9 and 2.7 μg/mL, respectively. The method was applied to determine terbinafine in pharmaceutical hydroalcoholic solutions and tablets with recoveries of 99.2%–99.8% for pharmaceutical solutions and 100.9%–102.1% for tablets. The method was also employed for a dissolution test. The tablet dissolution test was so fast that 80% of the drug was dissolved within 15 min. The method was also shown to be accurate, precise, specific and robust.

Using a C18 column as stationary phase and a 0.2% aqueous solution of sodium-1-heptanesulphonate (as an ion-pairing reagent) of pH 2 (adjusted with H3PO4)-acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) as mobile phase, TFH in tablets was determined by ion-pair reversed-phase-liquid chromatography [28]. The detection wavelength was set at 220 nm and the method was applied over a concentration range of 8.54–59.8 μg/mL, with LOD and LOQ values of 1.21 and 3.67 μg/mL, respectively. The method’s repeatability was 0.90% (RSD) and reproducibility was 0.92% (RSD). When applied to 250 mg tablets, the method yielded results which were accurate to 99.83% of label claim with a standard deviation of 0.29. The chromatogram of the tablet extract did not show additional peaks, which proved the selectivity of the method against the tablet excipients.

TFH was chromatographed on RP-C18 column with a mobile phase consisting of buffer-acetonitrile (65:35, v/v) pumped at a flow rate of 1.8 mL/min with UV-detection at 220 nm [29]. The calibration graph was linear over the concentration range of 0.02–2 µg/mL. The method showed excellent precision with intra- and inter-day variation of <2% (RSD) and high accuracy with an RE of 0.9%. The method was applied to determine TFH in 250 mg tablets of three brands and the average drug content was 99.52% of label claim with a standard deviation of 0.95.

By carrying out chromatography on an ODS column using a mixture of phosphate buffer and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) as mobile phase at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with UV-detection at 283 nm, TFH in tablets was assayed by a reversed-phase-high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) method [30]. The retention time of the drug was 7.1 min. The method produced linear response in the concentration range of 0.5–50 µg/mL (r=0.998). The method exhibited excellent intra- and inter-day precisions with RSD values of ≤1.04% and ≤1.44%, respectively. The method was applied to quantify the drug content in Daskil and Fungoteck tablets each containing 250 mg of TFH. The mean amounts (mg) of the drug obtained were 252.6±0.44 (Daskil) and 249.3±0.31 (Fungotech) indicating remarkable accuracy and precision of the method.

Chromatography was performed on an Inertsil C18 column to assay TFH in semi-solid dosage forms by HPLC [31]. The mobile phase consisted of methanol and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) with 0.15% triethylamine and 0.15% H3PO4 (pH 7.68) and eluents were monitored by photodiode array (PDA) detector set at 224 nm. The method was claimed to have been statistically validated for linear range, LOD, LOQ, accuracy, precision, specificity and robustness. The linear range was 5 to 50 µg/mL with LOD and LOQ values of 0.1 and 0.2 µg/mL, respectively. To develop an RP-HPLC method for TFH in cream formulation [32], chromatography was performed on a phenomenex C18 column (250 mm×4.6 mm, 5 µm) using water–acetonitrile–methanol (50:40:10, v/v/v) containing 0.1 mL of H3PO4 and triethylamine respectively as mobile phase with UV-detection at 282 nm. TFH present along with chlorhexidine and triamcinolone acetonide acetate in compound ointment has been determined using Kramosil C18 5 µm column [33]. A 0.3% sodium heptanesulphonate in methanol of pH 3.2 (adjusted with glacial acetic acid)-distilled water (73:27, v/v) was the mobile phase with UV-detection at 248 nm. The method, besides sensitive and specific, was accurate for the determination of three components with good resolution.

To accomplish simultaneous assay of TFH and bezafibrate in pharmaceutical dosage forms, separation and analysis were achieved by gradient elution on a C18 column with water–ammonium dihydrogenphosphate–methanol (15:25:60, v/v/v) as mobile phase. The mobile phase flow rate was 1 mL/min and the effluents were detected at 225 nm. The calibration graph was linear over the concentration range of 2–12 µg/mL (r=0.999)and LOD and LOQ values were 0.05 and 0.15 µg/mL, respectively. The method was found to be accurate with an RE of 0.46% and precise with an RSD of 0.75% [34].

Terbinafine in the presence of its photo-degradation products was determined by liquid chromatography [35] using an RP-μ-Bondapak C18 column (250 mm×4.6 mm, 10 μm) as stationary phase and water-methanol (20:80, v/v) as mobile phase with UV-detection at 284 nm. The method showed a significant stability-indicating ability with good linearity, precision and accuracy. Assay of TFH in tablets and creams has been reported using a Shim-pack CLC-ODS (250 mm×4 mm, 5 μm) column with water-methanol (5:95, v/v) as mobile phase in an isocratic mode at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and UV-detection at 254 nm. The calibration graph was linear over the range of 10–20 µg/mL (r2=0.9994). The method yielded excellent results when applied to tablets and creams, with an RE of 1.15%–3.3% and an RSD <1% [36]. The method was also validated for intra- and inter-day precisions (RSD, 0.02%–1.23%).

There are two reports describing the stability-indicating assay for the drug by HPLC. In a method applicable to bulk drugs and tablets, the analysis was carried out on a NeoSphere C18 (250 mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm) column with a mobile phase comprising of methanol and 0.5% triethanolamine at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min with a runtime of 8 min, and the eluents were monitored at 250 nm. The method was valid over the concentration range of 2–12 µg/mL with an LOD of 0.22 µg/mL and an LOQ of 0.66 µg/mL. The method was applied to tablets with satisfactory results and tablet excipients did not interfere in the assay [10]. As a part of stability-indicating assay, the drug was subjected to acid, base, and neutral (water) hydrolysis, and oxidative, thermal and photo degradation, and the drug was found to undergo slight degradation under acidic and photolytic stress conditions and to be unaffected under other stress conditions. In the second HPLC method devoted for the stability-indicating assay [37], separation and analysis were carried out on a ZORBAX Eclips XDB C18 (150 mm×4.6 mm, 3.5 μm) column at 30 °C with UV-detection at 222 nm. The mobile phase comprised buffer prepared by mixing 1000 mL water with 2 mL triethylamine (pH adjusted to 3.4 with trifluoroacetic acid): isopropyl alcohol: methanol (40:12:48, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. An excellent linearity was obtained over the range of 1–80 µg/mL with LOD and LOQ values of 0.3 and 1.0 µg/mL, respectively. The method, when applied to tablets, yielded results which were in good agreement with those of a reference method and were highly accurate and precise, and without any detectable interference from tablet excipients. To demonstrate the stability-indicating power of the method, the drug was subjected to forced degradation in accordance with the ICH guidelines, and the results indicated that the drug degraded slightly under oxidative stress condition and remained stable under other stress conditions.

Apart from being used for the quantitation of TFH in drug and drug products, HPLC was also applied for the separation and determination of the drug and its four impurities of similar structure [38]. In an improved RP-HPLC method, the active component, terbinafine, its one impurity, 1-methylaminomethylnaphthalene, and three degradation products, β-terbinafine, z-terbinafine and 4-methylterbinafine occurring in pharmaceutical formulations after long-term stability tests, were determined simultaneously using propylparaben as an internal standard. The chromatographic separation was performed on a NUCLEOSIL 100-5-CN column and the mobile phase for the separation of all compounds consisted of sodium citrate buffer of pH 4.5, tetrahydrofuran, and acetonitrile (70:10:20, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min, with UV-detection at 226 nm. The method was validated and system suitability parameters were investigated. LOD value for terbinafine degradation products or impurities was 0.023–0.098 µg/mL and LOQ value was 0.078–0.327 µg/mL. The method robustness and short-term standard solution stability were also verified. The method, which is claimed, is applicable for routine determination of terbinafine and all its found impurities of similar structure with sufficient selectivity, precision and accuracy.

Spectrodensitometric assay of TFH along with triamcinolone was achieved after separation by thin layer chromatography (TLC) [16]. It is a rapid and precise method for the separation and quantification of both TFH and triamcinolone. The assay was done by densitometric evaluation at 283 and 238 nm for TFH and triamcinolone, respectively. The method was applicable over the concentration ranges of 5–25 µg/spot (TFH) and 2.5–22.5 µg/spot (triamcinolone). The method was applied to the assay of TFH in laboratory prepared mixtures and pharmaceutical preparations and the results were in excellent agreement with those of a reference method. Terbinafine and its degradation products were assayed by a method [35] which depended on coupling the TLC-fractionation on silica gel 60F254 utilizing chloroform–methanol-25% aqueous ammonia (12:0.1:0.1, v/v/v) as mobile phase with direct scanning at 284 nm.

In addition to TLC, high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) also finds application for the assay of TFH in pharmaceuticals. In a method that could be applied to routine analysis [39], separation was achieved on aluminum plates pre-coated with silica gel 60F254, with toluene–ethylacetate–formic acid (4.5:5.5:0.1, v/v/v) as mobile phase, and densitometric analysis was performed at 284 nm. Compact band of the drug was obtained at an Rf value of 0.31±0.02. Linearity (r2=0.9985), LOQ (0.035 µg/band), recovery (97.6%–109.6%) and precision (RSD≤2.19%) were satisfactory. The method was reported to be applicable for accelerated stability-testing of the drug in pharmaceutical drug-delivery systems. Since the method was found to effectively separate the drug from its degradation products, it could be used as a stability-indicating one. In another method [40], pre-coated silica gel 60F254 aluminum foil TLC plate was used as stationary phase and the chromatogram was developed using n-hexane:acetone:glacialaceticacid (8:2:0.1, v/v/v) as mobile phase. A compact band at an Rf value of 0.42 was obtained for terbinafine. Densitometric analysis was performed in the absorbance mode at 223 nm using Camag TLC scanner. Linear relationship of peak area and drug concentration was excellent (r2=0.9997) in the concentration range of 0.2–1 µg/spot. The LOD and LOQ values were 0.0012 and 0.0036 µg/spot, respectively. The method was applied to bulk drugs and tablets with satisfactory results. The drug was subjected to acid, alkali, hydrolytic, oxidative, photochemical and thermal degradation, and the drug was found to undergo degradation only under photochemical stress condition by exposure to UV-light. An HPTLC method has been described for the assay of TFH in tablets [41] by employing aluminum back pre-coated silica gel 60F254 TLC plates as stationary phase and acetonitrile:1,4-dioxane:hexane:acetic acid (1:1:8:0.1, v/v/v/v) as mobile phase. After developing the chromatogram in a Camag chamber, densitometric scanning was performed with Camag TLC scanner-3 at 282 nm. The Rf value was 0.45. The standard graph was linear over the range of 0.5–5 µg/spot (r2=0.9975). The LOD and LOQ values were 0.30 and 0.39 µg/spot, respectively. The method was found to be precise with RSD values of 0.55%–0.97% (intra-day, n=3) and 0.33%–0.84% (inter-day, n=3). On applying the method to 250 mg commercial tablets, the method yielded results (249.87 mg) very close to the label claim. Table 4, Table 5 present the gist of these methods.

Table 4.

Performance characteristics of HPLC, UPLC and GC methods.

| S.No. | Stationary phase; Mobile phase | UV-detection (nm) | Linear range (μg/mL) | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C18 (150mm×3.0 mm, 5 μm); Buffer (0.2% triethylamine in water, pH 7.5 with acetic acid), acetonitrile, and methanol; 0.8 mL/min. | 280 | – | – | – | Bulk drug | [8] (USP method) |

| 2 | RP-C18(250mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm); methanol–water (95:5, v/v); 1.2 mL/min. | 254 | 20–200 | 0.9 | 2.7 | Pharmaceutical hydroalcoholic solutions and tablets, dissolution test | [27] |

| 3 | C18; 0.2% sodium-1-heptanesulphonate: acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) | 220 | 8.54–59.8 | 1.21 | 3.67 | Tablets | [28] |

| 4 | RP-C18; buffer:acetonitrile (65:35, v/v); 1.8 mL/min | 220 | 0.02–2 | – | – | Tablets | [29] |

| 5 | ODS column; phosphate buffer:acetonitrile (60:40, v/v); 1 mL/min | 283 | 0.5–50 | – | – | Tablets | [30] |

| 6 | Inertsil C18; methanol:acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) with 0.15% triethylamine and 0.15% H3PO4 (pH 7.68) | 224 | 5–50 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Semi-solid dosage forms | [31] |

| 7 | Phenomenex C18 (250mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm); water–acetonitrile–methanol (50:40:10, v/v/v) | 282 | – | – | – | Cream | [32] |

| 8 | Kramosil C18; distilled water-0.3% sodium heptanesulphonate in methanol (pH 3.2 with glacial acetic acid) (73:27, v/v) | 248 | – | – | – | Ointment | [33] |

| 9 | C18 column; water–ammonium dihydrogenphosphate–methanol (15:25:60, v/v/v); 1 mL/min. | 225 | 2–12 | 0.05 | 0.15 | Dosage forms | [34] |

| 10 | RP-Bondapak C18 (250mm×4.6 mm, 10 μm); water–methanol (20:80, v/v) | 284 | – | – | – | In the presence of photo degradation products (SIAM) | [35] |

| 11 | Shim-pack CLC-ODS (250×4 mm, 5 μm); water:methanol (5:95, v/v); 1 mL/min. | 254 | 10–20 | – | – | Tablets and creams | [36] |

| 12 | NeoSphere C18 (250mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm); 0.5% triethanolamine and methanol; 1.2 mL/min | 250 | 2–12 | 0.22 | 0.66 | Stability-indicating assay; bulk drug and tablets | [10] |

| 13 | ZORBAX Eclips XDB C18 (150mm×4.6 mm, 3.5 μm); 0.2% triethylamine buffer (pH 3.4 with trifluoroacetic acid):isopropyl alcohol:methanol (40:12:48, v/v/v); 1 mL/min. | 222 | 1–80 | 0.3 | 1.0 | Stability-indicating assay, tablets | [37] |

| 14 | NUCLEOSIL 100-5-CN; Sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5)-tetrahydrofuran–acetonitrile (70:10:20, v/v/v); 0.8 mL/min | 226 | – | – | – | Separation of impurities | [38] |

| 15 | Buffer (0.012 mol/L triethylamine+0.02 mol/L H3PO4) and acetonitrile (50:50, v/v) | 224 | 0.02–2 | 0.002 | – | Human plasma, nail, sebum, and stratum corneum; Pharmacokinetic solution | [49] |

| 16 | Phenyl column | 224 | 0–2.5 (plasma) | 0.02–0.5 | – | Human plasma and urine | [50] |

| 0–1 (urine) | |||||||

| 17 | MerckLichro CART (250mm×4 mm, 5 μm); 0.05% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid, acetonitrile, and methanol | 224 | 0.1–15 | 0.31 | 0.95 | Urine | [51] |

| 18 | – | UV and electro chemical | – | 0.05 (plasma) | – | Plasma, milk and urine | [52] |

| 0.15 (milk) | |||||||

| 0.3 (urine) | |||||||

| 19 | C18 column; water and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) containing H3PO4 (0.02 mol/L) and triethylamine (0.01 mol/L) | 224 | 1–3 µg/g (skin) | – | 0.1 µg/g (skin) | Rat tissues | [53] |

| 0.01–0.6 µg/g (other tissues) | 0.01 µg/g (other tissue) | ||||||

| 20 | – | – | – | – | Nail samples | [54] | |

| 21 (a) | Pecosphere 3 C18 (83mm×4.6 mm, 3 μm); 0.012 mol/L triethylamine+0.02 mol/L H3PO4: acetonitrile (48:52, v/v); 2.0 mL/min. | 224 (HPLC) | 0.0003–3 | – | 0.01 μg/g | Cat hair | [55] |

| (b) | Capillary HP-5 column (30 m×250 μm×0.25 μm); carrier gas was helium | FID Detector (GC) | 0.025–5 | – | 0.0006 µg/g | – | |

| 22 | ZORBAX SB-Aq C18 column; 50% H3PO4:acetonitrile (40:60, v/v); 0.8 mL/min. | – | – | – | – | Human plasma | [56] |

| 23 | Hypersil GOLD C18 (50mm×2.1 mm, 1.7 μm); 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile (UPLC) | – | – | 0.01–0.07 | – | Plasma and urine | [57] |

SIAM: Stability-indicating assay method.

Table 5.

Performance characteristics of TLC and HPTLC methods.

| S.No. | Stationary phase; Mobile phase | Detection (nm) | Linear range (µg/spot) | LOD (µg/spot) | LOQ (µg/spot) | Application | Reference |

| 1 | Spectrodensitometry | 283 | 5–25 | – | – | Pharmaceutical preparations containing TFH and triamcinolone | [16] |

| 2 | Silica gel 60F254; 25% aqueous ammonia–chloroform–methanol (0.1:12:0.1, v/v/v) | 284 | – | – | – | Bulk drug, degradation products | [35] |

| 3 | Silica gel 60F254; Formic acid-toluene–ethylacetate (0.1:4.5:5.5, v/v/v) | 284 | – | – | 0.035 | Pharmaceuticals, accelerated stability testing | [39] |

| 4 | Silica gel 60F254; n-hexane: acetone: glacial acetic acid (8:2:0.1, v/v/v) | 223 | 0.2–1 | 0.0012 | 0.0036 | Bulk drug and tablets; SIAM | [40] |

| 5 | Silica gel 60F254; acetonitrile: 1,4-dioxane: hexane: acetic acid (1:1:8:0.1, v/v/v/v) | 282 | 0.5–5 | 0.30 | 0.39 | Tablets | [41] |

SIAM: Stability-indicating assay method.

2.8. Capillary electrophoresis methods

A capillary electrophoresis method developed for the separation and determination of terbinafine in various pharmaceutically relevant mixtures [42] involved separation by capillary zone electrophoresis and UV-absorbance detection at 224 nm. The separation and analysis were performed using a hydrodynamically closed 160 mm capillary tube (300 μm i.d.). The influences of pH, carrier cation and counter ion on migration parameters of the drug were studied. The method was applicable over the concentration range of 6–60 µmol/L with an LOD of 1.73 µmol/L. Under optimum conditions described, the method was applied to the determination of terbinafine in commercial tablets and sprays with an RE of 0.64% (tablets) and 0.53% (sprays). Another article described an electrochemical method involving capillary electrophoresis (CE) with contactless conductivity detection, and amperometry associated with batch injection analysis, for the determination of TFH in pharmaceutical products [43]. In the CE method, terbinafine was protonated and analyzed in the cationic form within 1 min. A linear range from 1.46 to 36.4 μg/mL in acetate buffer solution and an LOD of 0.11 μg/mL were achieved. In amperometric studies, terbinafine was oxidized at +85 V with high throughput (225 injections/h) and good linear range (10–1000 µmol/L). There was also a description of the assay for this antifungal agent using simultaneous conductometric and potentiometric titrations in the presence of 5% ethanol with NaOH as titrant. Electrochemical methods were applied to the quantification of TFH in different samples, and the results agreed with the label claim and were comparable to those found using pharmacopoeial titrimetric method.

Two rapid and efficient electrophoresis methods (phosphate buffer method and formic acid method) have been developed for the analysis of terbinafine by capillary zone electrophoresis [44]. Resolutions higher than 1.5 were achieved with 0.025 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 2.30) and 0.2 mol/L formic acid (pH 2.15) with an applied voltage of 20 kV and a temperature of 30 °C. Both methods yielded calibration graphs which were linear over a concentration range 0.5–15 μg/mL. The LOD and LOQ values were 0.40 and 1.30 μg/mL (phosphate buffer method) and 0.22 and 0.72 μg/mL (formic acid method). Better sensitivity and selectivity were achieved in phosphate buffer whereas formic acid system yielded shorter analysis time. The reproducibility obtained for migration time (RSD≤1.0%, n=10) and peak areas (RSD≤4.3%, n=10) were acceptable. These details are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Methodology and performance characteristics of capillary electrophoresis methods.

| S.No. | Buffer | Detection (nm) | Linear range (μg/mL) | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 224 | 6–60 μmol/L | 1.73 μmol/L | – | Tablets and sprays | [42] |

| 2 | Acetate buffer solution | Conductivity and amperometry | 1.46–36.4 | 0.11 | – | Pharmaceutical products | [43] |

| 10–1000 μmol/L | |||||||

| 3 (a) | Phosphate buffer (pH 2.30) | – | 0.5–15 | 0.40 | 1.30 | – | [44] |

| (b) | Formic acid (pH 2.15) | – | 0.5–15 | 0.22 | 0.72 | – | |

| 4 | 0.05 μmol/L | 220 | – | 0.08 μmol | 0.28 μmol | Body fluids | [62] |

| Phosphate buffer (pH 2.2) |

2.9. Microbiological assay

A microbiological assay, applying the cylinder-plate method for the determination of TFH, has been optimized [45]. Using a strain of Aspergillus flavus ATCC 15546 as the test organism, TFH with concentrations ranging from 0.125 to 0.5 μg/mL was determined. A perspective validation of the method showed good linearity (r=0.9998), precision (RSD<1.0%) and accuracy when applied to tablets and creams. The assay was found to be satisfactory for the quantification of in vitro antifungal activity of terbinafine (Table 7).

Table 7.

Performance characteristics of microbiological assay methods.

| S.No. | Method; Strain | Linear range (μg/mL) | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cylinder-plate method; Aspergillus flavus (ATCC 15546) | 0.125–0.5 | – | – | Tablets and creams; in vitro antifungal activity of TFH | [45] |

| 2 | Strain of Aspergillus flavus | – | 0.2–6.4 | – | Blood serum | [47] |

| 3 | Trichophyton mentagrophytes | 0.16–10 | – | – | Serum | [48] |

3. Methods for biological materials

Most of the methods developed for the determination of TFH in biological materials are based on different modes of liquid chromatography, and a few methods relying on spectrofluorimetry, voltammetry and microbiology are also found in the literature.

3.1. Spectrofluorimetric method

The spectrofluorimetric method described earlier for dosage forms [22] was extended to the determination of the drug in spiked human plasma and the results were satisfactory with a mean recovery of (99.57±1.04)% (Table 2).

3.2. Electrochemical methods

Voltammetric determination of TFH in human serum samples using GC electrode modified by cysteic acid or carbon nanotubes composite film was conducted without pretreatment of biological fluid [46]. The determination of TFH at the modified electrode was studied by DPV. The peak current obtained at +1.556 V (vs SCE) from DPV was linearly dependent on the drug concentration in the range of 8×10−8–5×10−5 mol/L (r=0.998) in a Britton–Robinson buffer solution of pH 1.81 and an LOD value of 2.5×10−8 mol/L. The low-cost modified electrode showed good sensitivity, selectivity and stability. It was supposed that the method could be applied to clinical and pharmacokinetic studies (Table 3).

3.3. Microbiological assay

Using a strain of Aspergillus flavus as the test organism, a specific agar diffusion bioassay for antifungal agent in blood serum, has been described [47]. The method was sensitive and could be applied over the concentration range of 0.2–6.4 μg/mL. In one of the earliest studies [48], a bioassay with trichophyton mentagrophytes was described for SF86-327, an allylamine antifungal agent (TFH). The drug concentration in serum was measured by bioassay in 117 serum samples from five patients receiving 500 mg/day. The peak, trough, and area under the concentration-time curve were determined after the first dose and at steady state condition. Drug accumulation occurred in prolonged therapy. The method was applicable over the concentration range of 0.16–10 μg/mL and the RSD values were high at the lowest concentrations. The method also used for organism with potential causing skin infections. Despite these limitations, it was a simple and useful method for determination of drug concentration in serum. Summary of these assays is presented in Table 7.

3.4. Chromatographic methods

Terbinafine and its desmethyl metabolite in human plasma have been determined by RP-HPLC [49]. The analytes and the internal standard were separated by liquid-liquid extraction followed by an aqueous back extraction before injecting the aqueous layer to HPLC system. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and 0.012 mol/L triethylamine+0.02 mol/L H3PO4 (50:50, v/v) and the effluents were monitored at 224 nm. The analytes were determined in the concentration range of 0.02–2 µg/mL with an RSD of 2.9%–9.8%. Because of the very high sensitivity (LOD, 0.002 µg/mL), it could be applied to pharmacokinetic studies.With additional pretreatment steps, it was supposed that the method could be used for assaying the drug in tissues such as nail, sebum, and stratum corneum. An isocratic HPLC method using on-line solid phase extraction has been described for the simultaneous determination of terbinafine and its five metabolites in human plasma and urine [50]. The compounds were separated on a phenyl column following on-line solid phase sample cleanup with a column-switching device. The drug and its metabolites were detected by monitoring the effluents at 224 nm. The drug and its metabolites were assessed in the range of 0–2.5 µg/mL in plasma and 0–1 µg/mL in urine LOQ values based on a 20% bias ranged from 0.02 to 0.5 µg/mL depending on the compound and matrix. However, the extraction efficiencies from the body fluids ranged from 55%–100% due to the considerable differences in hydrophobicity of the compounds.

A new and reliable gradient RP-HPLC method with a diode array detector (DAD) was developed and validated for the determination of terbinafine in urine [51]. The analysis was achieved on a Merck LiChroCART analytical (250 mm×4 mm, 5 µm) column using a mobile phase comprising of 0.05% aqueous trifluoroaceticacid, acetonitrile and methanol. The effluent was monitored by a DAD at 224 nm. The calibration graph was linear over the concentration range of 0.1–15 μg/mL with LOD and LOQ values of 0.31 and 0.95 μg/mL, respectively. The method applying to spiked human urine sample was found to be accurate with a percent bias of 0.06%–6% and the precision (RSD) ranged from 1.3% to 5.41%.

Analytical procedures were developed for the determination of terbinafine (I) and its dimethyl derivative (II) in plasma, milk and urine, and the metabolite carboxyterbinafine (III) in plasma and urine, as well as further metabolites, dimethyl carboxy terbinafine (IV) and naphtholic acid (V) in urine by HPLC [52]. The methods for plasma analysis employed either electrochemical detection (for I and II) or UV-detection (for III) following a protein precipitation with methanol or solvent extraction with hexane as appropriate. For quantitative analysis of substances I-IV, native urine samples were deconjugated, mixed with the internal standard and injected by an autosampler into a microprocessor-controlled HPLC system. The substances were monitored by UV-absorption. The metabolite V was determined in the urine after deconjugation, sample preparation with commercially available cartridge, and silylation by automated GC with fused silica capillary column and flame ionization detection (FID). The LOD for I and II was 0.05 µg/mL in plasma and 0.15 µg/mL in milk, and 0.1 µg/mL for III in plasma. The detection limit in urine was 0.3 µg/mL for I–IV analyzed by HPLC.

HPLC was also used for the simultaneous determination of terbinafine and its metabolite N-dimethyl terbinafine in rat tissues [53]. The method involved the homogenization of tissues (except for skin) followed by a liquid–liquid extraction. Skin samples were dissolved in NaOH prior to extraction. The drug and its metabolites were assayed using a RP-C18 column with a mobile phase composed of water and acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) containing H3PO4 (0.02 mol/L) and triethylamine (0.01 mol/L). UV-detection was at 224 nm, and clotrimazole was used as the internal standard. The standard curve for the assay was linear over the range of 0.1–3 µg/g in skin and 0.01–0.6 µg/g in all other tissues. The LOQ was 0.1 µg/g for skin and 0.01 µg/g for all other tissues. The precision (RSD) lay between 0.2% and 16%. In a related method, terbinafine in nail samples of patients treated orally with terbinafine for onychomycoses has been determined [54]. After extraction, the samples were measured by HPLC, and the results indicate rapid penetration of the drug into normal nail plate. Two methods using HPLC and GC have been compared and critically evaluated for the determination of TFH levels in cat hair after appropriate sample pretreatment, hydrolysis of hair samples followed by liquid–liquid extraction [55]. The HPLC was performed on a Pecosphere 3 C18 (83 mm×4.6 mm, 3 µm) column maintained at 45 °C. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile: 0.012 mol/L triethylamine+0.02 mol/L H3PO4 (52:48, v/v) at a flow rate of 2 mL/min with an isocratic elution mode, and the detector was set at 224 nm. The GC system used a capillary HP-5 coated with 5% phenyl methyl siloxane (30 m×250 µm×0.25 µm) on a temperature gradient mode using an FID detector. The carrier gas was helium at a flow rate of 11.8 mL/min. The HPLC method for the determination of TFH in cat hair had a linearity of 0.0003–3 µg/mL with an LOQ of 0.01 μg/g. With a linear range of 0.025–5 µg/mL and an LOQ of 0.0006 µg/g, the GC method was less sensitive compared to the HPLC method. And the latter was more accurate with a recovery of 93.8% against a recovery of 70% achieved by GC.

With ZORBAX SB-Aq C18 column, the optimized HPLC system was applied to the determination of terbinafine in human plasma [56] with a mobile phase consisting of 50% H3PO4–acetonitrile (40:60, v/v) at the flow rate of 0.8 mL/min using paraben as the internal standard (IS). The retention time was 17.43 and 7.27 min for the drug and IS, respectively. The developed method was transferred to UPLC with similar column packing, Water Aquity BEH C18 (50 mm×2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) column, and 50% H3PO4-acetonitrile (50:50, v/v) as mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The retention time of terbinafine and IS were 2.98 and 0.92 min, respectively. By this transfer, the analysis time was reduced by a factor of 6 compared to HPLC with a similar peak capacity. Simultaneous determination of furosemide and its active metabolite suluamine, spironolactone and its active metabolite canrenone, terbinafine and its metabolite N-demethylcarboxy terbinafine, and vancomycin in human plasma and urine have been determined by RP-UPLC with UV-detection [57]. Good separation and analysis of the analytes were achieved on a Hypersil GOLD C18 (50 mm×2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) column in 3.3 min with 0.1% formic acidand acetonitrile as the mobile phase. The LOD values varied from 0.1 to 0.07 μg/mL with vancomycin as an exception (0.11 μg/mL). The analysis was preceded by protein precipitation and solid phase extraction of the analytes from plasma and urine samples. Owing to short analysis time and small quantities of samples required, the methods could be advantageously applied to routine clinical analysis. Summary of these methods is presented in Table 4, Table 5.

3.5. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometric methods

A fully automated high throughput liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometric (LC–MS/MS) method was developed for terbinafine quantification in human plasma [58]. The drug and the internal standard (N-methyl-1-napthalenemethylamine) after extraction from human plasma by liquid–liquid extraction using a mixture of methyl tertiary butyl ether-hexane (70:30, v/v) as the organic solvent were analyzed on a reversed-phase LC-MS/MS with positive ion electrospray ionization and multiple reaction monitoring. The calibration curve was linear for 0.005–2 µg/mL concentration range, and the method had a very short sample preparation time and chromatographic runtime of 2.2 min. Hence, the method was applied to the rapid and reliable determination of the drug in plasma in a bioequivalence study after oral administration of 250 mg tablet of terbinafine. Using the same technique (LC–MS/MS), the determination of terbinafine in human and minipig plasma has been developed and validated [59]. The method used a positive ion mode to monitor terbinafine and used a stable isotope labeled terbinafine as the internal standard. Subsequent to acetonitrile protein precipitation, the unfiltered supernatant portion was injected on the LC column (retention time of nearly 4.3 min). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 0.0000679 µg/mL in human and minipig plasma using a plasma sample of only 0.08 mL. The method, besides being fast and specific, was demonstrated to exhibit ruggedness.

In an approach to applying the quantification of terbinafine in human plasma to bioequivalence study, the drug was assayed by HPLC coupled to electrospray tandem mass spectrometry [60]. The method used nuftifine as the internal standard and had a chromatographic runtime of 5 min. The standard plot was linear in the range of 0.001–2 µg/mL with an LOD of 0.001 µg/mL. The intra-day precision and accuracy were ≤4.1% (RSD) and ≤7.8% (RE), respectively. The method was used in a bioequivalence study of two 250 mg tablets of terbinafine. An LC–MS/MS instrument equipped with an electrospray ionization interface and operated in the positive ion mode of detection was used to determine terbinafine in human hair [61]. The procedure involved hydrolysis of 10 mg of human hair with 0.5 mL of 5 mol/L NaOH for 90 min followed by extraction with 1.5 mL of n-hexane. The separated organic layer was re-extracted with 0.2 mL of 12.5% formic acid and 2-propanaol (85:15, v/v). The aqueous layer was separated and 0.01 mL of the aqueous extract was injected onto an RP-microbore (50 mm×0.1 mm i.d) column for analysis. The method showed excellent specificity and ruggedness with an LLOQ of 0.01 µg/g using 10 mg of human hair. Gist of these methods is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Performance characteristics of liquid chromatography–mass spectrophotometric(LC–MS) methods.

| S.No. | Method | Detection | Linear range (µg/mL) | LOD (µg/mL) | LLOQ | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LC–MS/MS with positive ion electrospray ionization | Multiple reaction monitoring | 0.005–2 | – | – | Human plasma, bioequivalence study | [58] |

| 2 | LC–MS/MS | Positive ion mode Monitoring | – | – | 0.0000679 µg/mL | Human and minipig plasma | [59] |

| 3 | LC–MS/MS | Positive ion mode detection | 0.001–2 | 0.001 | – | Human plasma to bioequivalence study | [60] |

| 4 | LC–MS/MS | Positive ion mode detection | – | – | 0.01 µg/g | Human hair | [61] |

3.6. Capillary electrophoresis method

A rapid and simple capillary zone electrophoresis method for the determination of terbinafine and eight of its main metabolites after incubation with rat hepatic S9 fraction was developed [62]. All the nine components were base-line resolved in less than 4 min using a 0.05 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 2.2) without additives, after a solid phase cleanup procedure for these in vitro samples. A voltage of 15 kV was applied in separation and electropherograms were recorded at 220 nm. An LOD of 0.08 μg/mL and an LOQ of 0.28 μg/mL were obtained.

4. Challenges and conclusions

The review of the analytical methods reported for terbinafine showed that spectrophotometric, spectrofluorimetric, electrochemical, chromatographic, microbiological and capillary electrophoretic techniques have been applied to the determination of TFH in pharmaceuticals and biological materials. However, the HPLC with UV-detection system has been widely used for pharmaceuticals, and HPLC with mass and tandem mass spectrometric detector system has been largely employed for biological materials.

The reviewed UV-spectrophotometric methods lacked wide linear dynamic ranges and sensitivity, which could be tackled by enhancing the aqueous solubility of the drug using strategies such as covalent solubilization and micellar solubilization. In spite of the drug's ability to form colored products with a number of chromogenic agents, only a limited number of visible spectrophotometric methods based on a few reactions have been reported. There is some scope for developing methods based on ion-association reactions using many acidic anionic dyes, charge-transfer complexation reactions using substituted p-benzoquinone, polynitro phenols, nitro derivatives, etc., and oxidative coupling reactions involving MBTH and oxidants like cerium (IV), iron (III), iodate, dichromate, etc. The reviewed extractive spectrophotometric methods based on ion-association reactions were plagued by several disadvantages. In recent years, there has been a surge in the use of spectrophotometry without liquid-liquid extraction step as a sensitive tool in pharmaceutical analysis [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79]. This new approach can be used in place of extractive spectrophotometry for terbinafine. The sensitivity and selectivity of the reported acid dye technique [17], [18], [19] can be further improved by dissolving the formed ion-pair in either alcoholic H2SO4 or alcoholic KOH and measuring the dye color at appropriate wavelengths. The high sensitivity of the modified approach allows the determination of the drug in body fluids after appropriate sample treatment [80].

RP-HPLC with UV-detection is the most widely used chromatographic method for the determination of terbinafine in pharmaceuticals due to its high separation potential, selectivity and sensitivity. However, HPLC with other detector systems such as fluorescence, electrochemistry, capillary electrophoresis, MS or MS/MS is yet to be reported. With the advent of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines, the requirement of establishment of stability-indicating assay method (SIAM) has become more clearly mandated. The guidelines explicitely require conduct of forced decomposition studies under a variety of stress conditions like pH, light, oxidation, dry heat, etc., and separation of drug from degradation products, and the method is also expected to allow analysis of individual degradation products [81], [82]. None of HPLC methods reviewed has addressed this concern though the only stability-indicating HPLC method [38] is concerned with the separation and determination of three degradants formed after long-term storage. However, separation and determination of the degradants were not reported in the other two works [10], [37]. A systematic and comprehensive study is required to be done in this direction.

The reviewed UV-spectrophotometric [12] and HPTLC [39], [40] methods which are stability-indicating are concerned with bulk drugs and the study needs to be extended to dosage forms. Organic impurities can arise during the manufacturing process and storage of the drug substances. The criteria for their acceptance up to certain limits are based on the pharmaceutical studies or known safety data [83]. HPLC is the most convenient technique for the tasks of separation, detection and quantitation of such impurities. Though one impurity generated by long-term storage was assayed [38], attempt has not been made to separate and determine the process-related impurities by HPLC. Further, HPLC, despite being a versatile, sensitive and selective technique, has failed to find a mention in pharmacokinetic or bioequivalence studies of the drug. Attention has to be paid to developing HPLC methods for this study.

Most of the chromatographic methods reported for the determination of terbinafine in biological materials including blood plasma, serum, and urine relied on the use of HPLC with UV-detection and LC with mass or tandem mass spectrometric detection has been rarely used, and two such works by Dotsikas et al. [58] and de Oliveira [60] are focused on bioequivalence study. Body fluid is highly complex and extraction of the drug and its active or inactive metabolites has mainly been achieved with liquid–liquid extraction using different solvent systems. Liquid–liquid extractions are useful but have certain limitations. The extracting solvents are limited to those that are water immiscible, emulsions tend to form when solvents are shaken, and relatively large volumes of solvents are used that generate a substantial waste disposal problem. The operations are often manually performed and may require a back extraction. However, many of these difficulties are avoided by the use of solid phase extraction (SPE), which has become a widely used technique for sample cleanup and concentration prior to chromatographic analysis [84]. However, none of the chromatographic methods reviewed uses SPE for the extraction of the drug or its metabolites from biological materials. Due to the advantages of SPE, it is likely that the methods, chromatography in particular, would be developed in future using SPE.

HPLC with UV or MS detection is the most widely used technique for the analysis of drugs in pharmaceutical and biological samples. The disadvantages of the technique are relatively long runtime and consumption of large volumes of expensive organic solvents creating the problem of waste disposal. In the last decade, there have been attempts to transform pharmaceutical analysis methods from HPLC to a relatively new technique, called UPLC, thereby creating new possibilities in LC, especially concerning the decrease in time and solvent consumption [85]. UPLC system allows shortening analysis time up to 5–7 times while solvent consumption is decreased by 6–9 times compared with conventional HPLC. Besides, the sensitivity and the resolution were also improved. In spite of these advantages, UPLC has never been applied for the assay of terbinafine in pharmaceuticals, although one HPLC method developed for human plasma [56] was transferred to UPLC with reduction in the analysis time by a factor 6 and large savings in terms of solvent consumption. Application of this new approach in LC is worth considering in future research on analytical method development for terbinafine.

Electrochemical methods have been proven to be highly useful for the assay of drugs, because of their sensitivity and selectivity. The methods also allow a good understanding of electrode mechanisms. Redox properties of drugs provide useful information about their metabolic fate or their in vitro redox properties or pharmaceutical activity [86], [87]. Many voltammetric techniques are highly sensitive which can determine electroactive species at 10−3–10−11 mol/L concentration levels [88]. Though the terbinafine molecule is electroactive, only four references are found in the literature dealing with the determination of the drug in pharmaceuticals and only one method [46] has been extended to human serum. Many more voltammetric techniques can be developed in future targeting olefinic double and triple bonds in the drug molecule. Electrochemical detection systems including amperometric and conductometric detection can be incorporated into HPLC to make it more versatile in the assay of the drug in pharmaceuticals and biological materials.

In the last couple of decades, dynamic development of CE methods for the analysis of drugs has been noticed [89], [90], but the method presents limited applications in the assay of terbinafine since only three references are found in the literature [42], [43], [44]; and only one method by Grego et al. [62] was applied to body fluids. This might be due to its low sensitivity, which can be overcome by coupling the techniques with MS or MS/MS.

Finally, a wide range of techniques are available for the assay of terbinafine in pharmaceuticals and biological materials. Analysis of the review of the methods reveals that HPLC with UV detection is extensively used for the determination of the drug in pharmaceuticals and biological materials. Considering the speed, sensitivity and cost effectiveness, direct UV spectrophotometry can be used if the matrix effect is absent or derivative mode can be considered as an alternative to circumvent the matrix effect. Wherever possible, HPLC with UV detection can be regarded as a better method since it is sensitive and selective, and the low cost compared to most advanced detection systems. For the determination of the drug in biological samples, HPLC–MS/MS is ideally suited since it combines the separation ability of HPLC with sensitivity and selectivity of MS, which allows the unambiguous detection of terbinafine and its metabolites. It would be a greener option if SPE precedes the analysis. This review presents an overview of the current state of analytical methods for the determination of terbinafine.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors (Prof. K Basavaiah) is thankful to the University Grants Commission, New Delhi, India, for the award BSR Faculty Fellowship.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

References

- 1.The Merck Index, 14th Edition, Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, N.J, 2006, Monograph No. 0009156.

- 2.Gokhale V.M., Kulkarni V.M. Understanding the antifungal activity of Terbinafine analogues using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000;8:2487–2499. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Web of informations database, Charles University, 2004. 〈http://bi.cuni.cz〉

- 4.Gupta A.K., Ryder J.E., Nicol K. Superficial fungal infections: an update on pityriasisversicolor, seborrheic dermatitis, tineacapitis, and onychomycosis. Clin. Dermatol. 2003;21:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthwise® for every health decision®, Terbinafine, 2004. 〈http://health.yahoo.com/topic/skinconditions/medications/drug/healthwise/d04012a1〉

- 6.European Pharmacopoeia, EDQM, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France, Edition 7.0, 2011, pp. 3047–3048.

- 7.British Pharmacopoeia, Her Majesty's, Stationery office, London, 2012, pp. 2112–2113.

- 8.United States Pharmacopoeia, USP35, National Formulary-32, Rockville, USP Convention, 2012, pp. 4789–4790.

- 9.Cardoso S.G., Elfrides E.S.S. UV spectrophotometry and nonaqueous determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in dosage forms. J. AOAC Int. 1999;82:830–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goswami P.D. Development and validation of spectrophotometric method for the determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in bulk and in tablet dosage form. Int. J. Pharm. Technol. 2013;5:5441–5447. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel K.K., Marya B.H., Kakhanis V.V. Spectrophotometric determination and validation for Terbinafine hydrochloride in pure and in tablet dosage form. Pharm. Lett. 2012;4:1119–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penmatsa V.K., Basavaiah K. Stability indicating UV-spectrophotometric assay of Terbinafine hydrochloride in dosage forms. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2013;5:2645–2655. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goswami P.D. Validated spectrophotometric method for the estimation of Terbinafine hydrochloride in bulk and in tablet dosage form using inorganic solvent. Pharm. Lett. 2013;5:386–390. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain P.S., Chaudhari A.J., Patel S.A. Development and validation of the UV-spectrophotometric method for the determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in bulk and in formulation. Pharm. Methods. 2011;2:198–202. doi: 10.4103/2229-4708.90364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel-Moety E.M., Kelani K.O., Abou Al-Alamein A.M. Spectrophotometric determination of Terbinafine in presence of its photodegradation products. Bull. Chim. Farm. 2002;141:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Saharty Y.S., Hassan N.Y., Metwally F.H. Simultaneous determination of Terbinafine HCl and Triamcinolone acetonide by UV derivative spectrophotometry and spectrodensitometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2002;28:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(01)00692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florea M., Monciu C.M. Spectrophotometric determination of Terbinafine through ion-pair complex formation with methyl orange. Farmacia. 2008;56:393–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elazazy M.S., El-Mammli M., Shalaby A. Application of certain ion - pairing reagents for extractive spectrophotometric determination of Flunarizine hydrochloride, Ramipril, and Terbinafine hydrochloride. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia. 2008;5:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chennaiah M., Veeraiah T., Kumar T.V. Extractive spectrophotometric methods for determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in pharmaceutical formulations using some acidic triphenylmethane dyes. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2012;19:218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrutyunjayarao R., Naresh S., Pendem K. Three simple spectrometric determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride (TRB) in pure state and tablets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India A. 2012;82:221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karuna T., Neelima K., Venkateshwarulu G. Spectrophotometric determination of drugs with iodine. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2006;65:808–811. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belal F., Sharaf El-Din M.K., Eid M.I. Spectrofluorimetric determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride and Linezolid in their dosage forms and human plasma. J. Fluoresc. 2013;23:1077–1087. doi: 10.1007/s10895-013-1237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mielech-Lukasiewicz K., Dabrowska A. Comparison of boron-doped diamond and glassy carbon electrodes for determination of Terbinafine in pharmaceuticals using differential pulse and square wave voltammetry. Anal. Lett. 2014;47:1697–1711. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faridbod F., Ganjali M.R., Norouzi P. Potentiometric PVC membrane sensor for the determination of Terbinafine. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013;8:6107–6117. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samy A.I., Sayed S.A., Haroon A.A. Conductimetric determination of cyproheptadine, Cetirizine, and Terbinafine hydrochlorides through the formation of ion-associates with manganese and zinc thiocyanate complexes. J. Drug Res. 2005;26:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arranz A., Betono S.F., Moreda J.M. Voltammetric behaviour of the antimycotic Terbinafine at the hanging drop mercury electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1997;351:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tagliari M.P., Kuminek G., Borgmann S.H.M. Terbinafine: optimization of a LC method for quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical formulations and its application for a tablet dissolution test. Quim. Nova. 2010;33:1790–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Florea M., Arama C.C., Monciu C.M. Determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride by ion-pair reversed phase liquid chromatography. Farmacia. 2009;57:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gopal P.N.V., Hemakumar A.V., Padma S.V.N. Reversed-phase HPLC method for the analysis of Terbinafine in pharmaceutical dosage forms. Asian J. Chem. 2008;20:551–555. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rani B.S., Reddy P.V., Babu G.S. Reverse phase HPLC determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in tablets. Asian J. Chem. 2006;18:3154–3156. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassem H., Almardini M.A. High performance liquid chromatography method for the determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in semi solids dosage form. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013;21:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domadiya V., Singh R., JatRakesh K. Method development and validation for assay of Terbinafine HCl in cream by RP-HPLC method. Inventi Impact: Pharm. Anal. Qual. Assur. 2012:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji X.F., Yu K.Y., Zhang W. Determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride, Chlorhexidine and Triamcinolone acetonide acetate in compound ointment by RP-HPLC. Chin. J. Pharm. Anal. 1997;17:363–365. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raju R.R., Babu N.B. Simultaneous analysis of RP-HPLC method development and validation of Terbinafine and Bezafibrate drugs in pharmaceutical dosage form. Pharmacophore. 2011;2:232–238. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdel M.E.M., Kelani K.O., Al-Alamei A.M. Chromatographic determination of Terbinafine in presence of its photodegradation products. Saudi Pharm. J. 2003;11:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardoso S.G., Schapoval E.E. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay of Terbinafine hydrochloride in tablets and creams. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1999;19:809–812. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(98)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vamsi K.P., Basavaiah K. Simple, sensitive and stability indicating high performance liquid chromatographic assay of Terbinafine hydrochloride in dosage forms. Am. J. PharmTech Res. 2014;4:899–916. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matysova L., Solich P., Marek P. Separation and determination of Terbinafine and its 4 impurities of similar structure using simple RP-HPLC method. Talanta. 2006;68:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmad S., Jain G.K., Faiyazuddin M. Stability-indicating high-performance thin layer chromatographic method for analysis of Terbinafine in pharmaceutical formulations. Acta Chromatogr. 2009;21:631–639. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suma B.V., Kannan K., Madhavan V. HPTLC method for determination of Terbinafine in the bulk drug and tablet dosage form. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2011;3:742–748. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel K.K., Karkhanis V.V. A validated HPTLC method for the determination of Terbinafine hydrochloride in pharmaceutical dosage forms. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012;3:4492–4495. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikus P., Valásková I., Havránek E. determination of Terbinafine in pharmaceuticals and dialyzates by capillary electrophoresi. Talanta. 2005;65:1031–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felix F.S., Ferreira L.M.C., Pamela O.R. Quantification of Terbinafine in pharmaceutical tablets using capillary electrophoresis with contactless conductivity detection and batch injection analysis with amperometric detection. Talanta. 2012;101:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cargo A.L., Marina M.L., Lareandera J.L. Optimization of a separation of antifungals by capillary zone electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. 2001;A 917:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00664-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cardoso S.G., Schapoval E.E.S. Microbiological assay for Terbinafine hydrochloride in tablets and creams. Int. J. Pharm. 2000;203:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C., Mao Y., Wang D. Voltammetric determination of Terbinafine in biological fluid at glassy carbon electrode modified by cysteic acid/carbon nanotubes composite film. Bioelectrochemistry. 2008;72:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haeuser M., Schmitt H.J., Bernard E.M. A new bioassay for Terbinafine. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1988;7:531–533. doi: 10.1007/BF01962608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kan V.L., Henderson D.K., Bennett J.E. Bioassay for SF 86-327, a new antifungal agent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986;30:628–629. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.4.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Denoueel J., Keller H.P., Schaub P. Determination of Terbinafine and its desmethyl metabolite in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. 1995;663:353–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00449-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zehender H., Denoueel J., Roy M. Simultaneous determination of Terbinafine (Lamisil) and five metabolites in human plasma and urine by high performance liquid chromatography using online solid-phase extraction. J. Chromatogr. B. 1995;664:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00483-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baramosuka I., Markowski P., Baranowski J. Development and validation of an HPLC method for the simultaneous analysis of 23 selected drugs belonging to different therapeutic groups in human urine samples. Anal. Sci. 2009;25:1307–1311. doi: 10.2116/analsci.25.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schatz F., Haberl H. Analytical methods for the determination of Terbinafine and its metabolites in human plasma, milk and urine. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1989;39:527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeganeh M.H., McLachlan A.J. Determination of Terbinafine in tissues. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2000;14:261–268. doi: 10.1002/1099-0801(200006)14:4<261::AID-BMC983>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dykes P.J., Thomas R., Finlay A.Y. Determination of Terbinafine in nail samples during systemic treatment for onychomycoses. Br. J. Dermatol. 1990;123:481–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuzner J., Erzen N.K., Drobnic-Kosork M. Determination of terbinafine hydrochloride in cat hair by two chromatographic methods. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2001;15:497–502. doi: 10.1002/bmc.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.UnalOzer D. HPLC-UV method transfer for UPLC in bioanalytical analysis: determination of Terbinafine from human plasma. J. Fac. Pharm. Istanbul Univ. 2011;41:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baranowska I., Wilczek A., Baranowski J. Rapid UHPLC method for simultaneous determination of Vancomycin, Terbinafine, Spironolactone, Furosemide and their metabolites: application to human plasma and urine. Anal. Sci. 2010;26:755–759. doi: 10.2116/analsci.26.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dotsikas Y., Apostolou C., Kousoulos C. An improved high-throughput liquid chromatographic/tandem mass spectrometric method for Terbinafine quantification in human plasma, using automated liquid-liquid extraction based on 96-well format plates. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2007;21:201–208. doi: 10.1002/bmc.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brignol N., Bakhtiar R., Dou L. Quantitative analysis of Terbinafine (Lamisil) in human and minipig plasma by liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2000;14:141–149. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(20000215)14:3<141::AID-RCM856>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]