Abstract

This study investigated the trophic transfer, individual impact, and embryonic uptake of fluorescent nano-sized polystyrene plastics (nanoplastics) through direct exposure in a freshwater ecosystem, with a food chain containing four species. The alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, water flea Daphnia magna, secondary-consumer fish Oryzias sinensis, and end-consumer fish Zacco temminckii were used as test species. In the trophic transfer test, algae were exposed to 50 mg/L nanoplastics, defined as plastic particles <100 nm in diameter; higher trophic level organisms were exposed through their diet. In the direct exposure test, each species was directly exposed to nanoplastics. Microscopic analysis confirmed that the nanoplastics adhered to the surface of the primary producer and were present in the digestive organs of the higher trophic level species. Nanoplastics also negatively affected fish activity, as measured by distance traveled and area covered, and induced histopathological changes in the livers of fish that were directly exposed. Additionally, nanoplastics penetrated the embryo walls and were present in the yolk sac of hatched juveniles. These observations clearly show that nanoplastics are easily transferred through food chain, albeit because of high experimental dosages. Nevertheless, the results strongly point to the potential health risks of nanoplastic exposure.

Introduction

Every year, enormous amounts of plastics are produced and discarded into the aquatic environment1–5; these are slowly eroded and weathered into small particles by physical, chemical, and biological processes6,7 and can accumulate in aquatic environments, including the sea1, shorelines3, estuaries8, beach sediments9, lakes10,11, and freshwater ecosystems12. Plastic particles <5 mm in diameter are called microplastics and those <100 nm in diameter are called nanoplastics1,13,14. Studies on plastic litter in the oceans date to the 1970s15–19. Serious concerns about micro- and nanoplastics in aquatic ecosystems arose in the 2000s, because of their abundance in marine ecosystems1,19–24 and discovery in the bodies of marine organisms25–30.

Micro- and nanoplastics may induce various toxic and adverse effects in aquatic organisms31–39. Several studies have reported that microplastics can carry contaminants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAA), persistent organic pollutants (POPs), pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PPCPs), and metals, into aquatic media because of their physicochemical properties5,40–43. Plastics contain not only polymers but also additive chemicals such as plasticizers, antioxidants, UV stabilizers, and flame retardants, which could be released into aquatic environments44–46, causing harm to aquatic organisms47–49. These contaminants may be transferred through the food chain to predators at upper trophic levels46,50–52. Their presence poses a considerable threat to aquatic ecosystems, the health of aquatic organisms, and human health. Therefore, the fate and behavior of micro- and nanoplastics in ecosystems, and their transfer between organisms and from organisms to the environment, must be examined.

In the present study, we chose fluorescent nano-sized polystyrene (nPS) as the model nanoplastic material whose transfer along the food chain is readily observable in laboratory tests. Using this material, we investigated the trophic transfer of this fluorescent nPS in a freshwater ecosystem, through a food chain consisting of four species, and recorded the effects of this material on aquatic organisms. We assumed that nanoplastics can be transferred to higher trophic level aquatic organisms and may negatively affect their health via dietary exposure (through food ingestion) and direct exposure (every form of contact, including food ingestion). The main goal of this study was to assess the transfer of these particles from freshwater algae, the primary producer, to carnivorous fish, the end consumer. In addition, we assessed the effects of nanoplastics on each aquatic organism.

Results

Characteristics of nPS

The size distributions, zeta (ζ)-potentials, and electron microscope images of nPS particles are shown in Fig. S1. Average diameters of nPS particles were 60.39, 57.45, and 57.29 nm in distilled water (DW), moderately hard water (MHW), and tris-acetate-phosphate medium (TAP), respectively. ζ-Potentials of nPS in each medium were −42.1, −17.4, and −14.1 mV in DW, MHW, and TAP, respectively. Mean diameters of nPS in DW and each test medium varied slightly, but the particles were rarely aggregated. The absolute values of ζ-potentials declined in test media, indicating that nPS particles are less stable in MHW and TAP.

Visual evidence of nPS trophic transfer

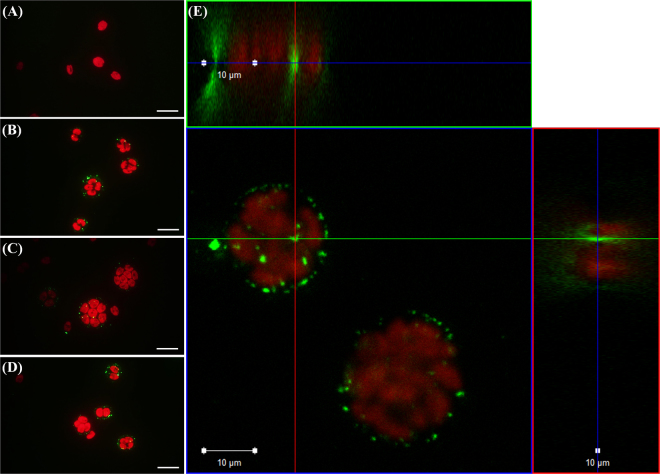

Due to direct exposure, nPS attached to the surface of C. reinhardtii (Fig. 1). Unlike the control group (Fig. 1a), the exposed groups (Fig. 1b–d) showed clearly separated red (auto-fluorescence of algae) and green (nPS fluorescence) emissions. Via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), we confirmed that nPS penetrated the outer layer of C. reinhardtii during cell division and attached to the surface of zoospores (Fig. 1e).

Figure 1.

Observation via optical microscopy (a–d) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (e) of the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (red emissions) directly exposed to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS; green emissions) for 72 h. Scale bar = 20 (a–d) and 10 μm (e).

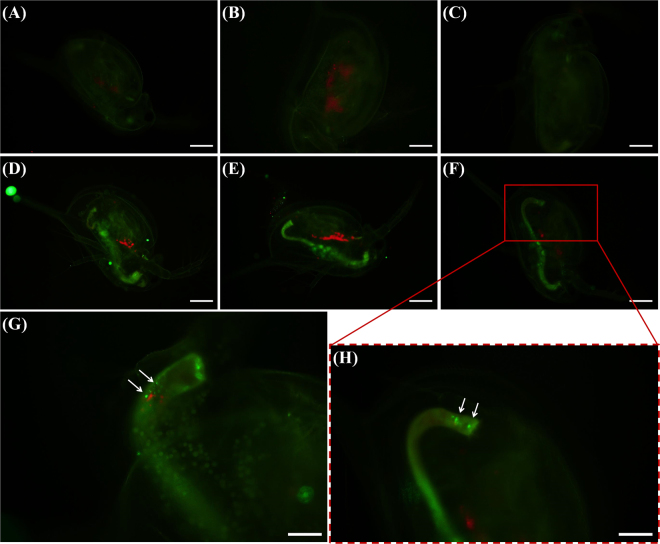

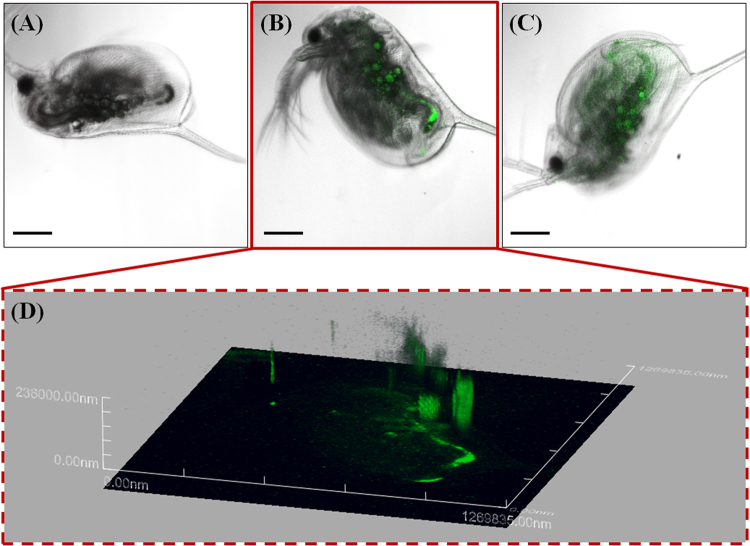

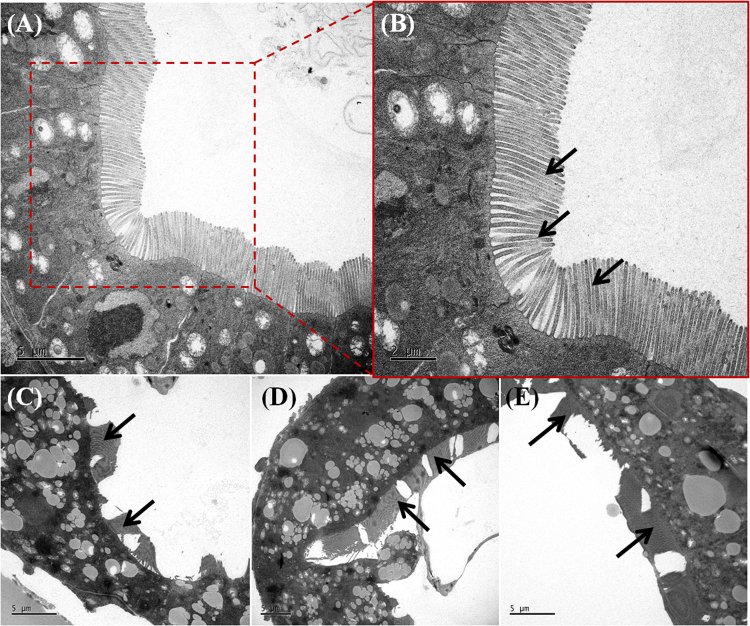

The attached nPS evidently transferred to D. magna through filter feeding and was observed in the gut of D. magna under the microscope (Fig. 2). Compared with control groups (Fig. 2a–c), exposed groups (Fig. 2d–h) showed distinct green fluorescence in their guts. Aggregated nPS was found at the terminal end of the guts of D. magna (Fig. 3g,h). We analyzed D. magna via CLSM and used Z-stack imaging to confirm the presence of nPS in the inner guts. Figure 3 compares the CLSM analysis of control individuals (Fig. 3a) and exposed individuals (Fig. 3b,c) and shows the Z-stack image of the exposed individual from Fig. 3b (Fig. 3d). We also used bio-transmission electron microscopy (Bio-TEM) to analyze the gut and microvilli of D. magna that were exposed through the diet to C. reinhardtii contaminated with nPS (Fig. 4). Control group D. magna were undamaged (Fig. 4a,b), whereas exposed D. magna had squashed and torn-out microvilli (Fig. 4c–e). This visual evidence confirms that nPS enters the guts and causes histological damage to the intestinal walls of D. magna through trophic transfer.

Figure 2.

Green fluorescence of nano-sized polystyrene (nPS) in Daphnia magna that had consumed Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (red fluorescence). Control groups (a–c), exposed groups (d–h), and expanded pictures of exposed individuals (g,h). Scale bar = 200 (a–f) and 100 μm (g,h).

Figure 3.

Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of Daphnia magna that were not exposed to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS; green emissions) (a) and that were exposed through the diet (b,c). Z-stack image of individual exposed through the diet (b), observed using CLSM (d). Z-stack image (d) provides evidence of nPS uptake through dietary exposure of D. magna. Green fluorescent nPS was observed in the gut of exposed D. magna. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of the transverse sectioned gut wall and microvilli (black arrows) in Daphnia magna. The guts and microvilli of D. magna that consumed non-exposed algae (a,b) and algae that were exposed to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS) (c–e) were observed. (a) Scale bar = 5 (a,c–e) and 2 μm (b).

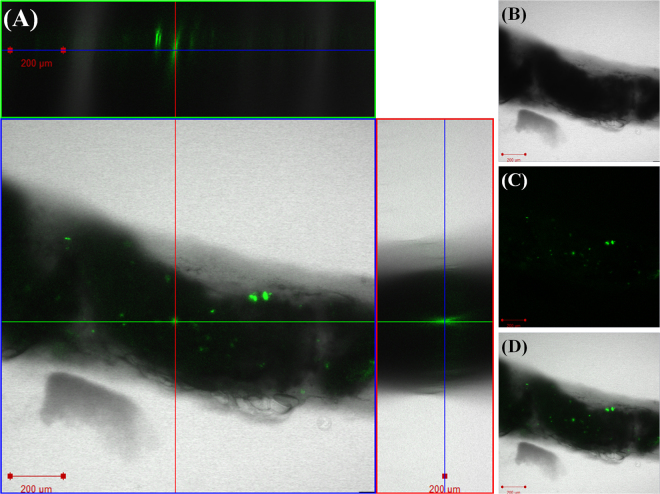

At the next level of dietary exposure, there was no fluorescence in the gut of control fish (Fig. S2a,b) but the green fluorescence of nPS was observed in the guts of exposed O. sinensis (Fig. S2c,d). To confirm that nPS entered the gut of O. sinensis, the extracted intestines of O. sinensis were also observed via CLSM (Fig. 5). The green fluorescence of nPS was clearly observed in the intestines, confirming the entry of nPS into the intestine via the food chain (Fig. 5a). In addition, the fluorescence of nPS in the feces of O. sinensis was observed under optical microscope with a fluorescent filter (Fig. S3).

Figure 5.

Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of Oryzias sinensis intestines after the fish consumed D. magna that were exposed to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS; green emissions). Z-stack images (a) confirmed the presence of nPS in the intestines of O. sinensis, as did merged CLSM images of optical image (b), fluorescent-only image (c), and merged image (d). Scale bar = 200 μm.

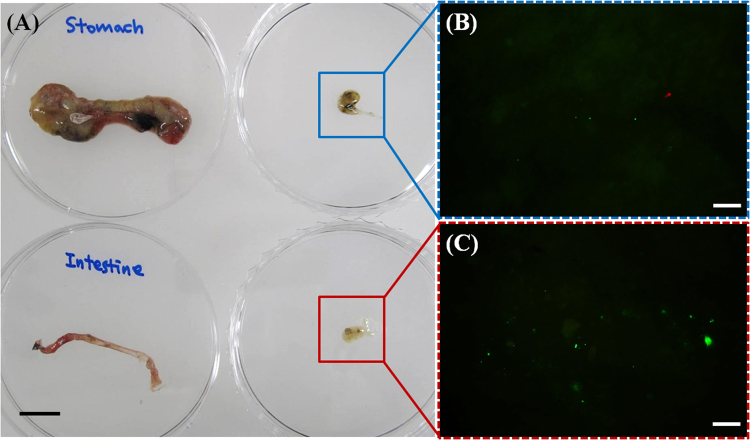

The final trophic transfer of nPS from O. sinensis to Z. temminckii was observed through an analysis of the extracted stomach and intestines of Z. temminckii. As shown in Fig. 6, the stomach and intestines from exposed Z. temminckii contained nPS from the consumed O. sinensis. More nPS was observed in the intestines (Fig. 6c) than in the stomach (Fig. 6b). There were also differences in fluorescence in the feces of control and exposed fish (Fig. S4). Under an optical microscope with a fluorescent filter, (Fig. S4a), the feces of exposed fish had brighter green fluorescence than the feces of control fish (Fig. S4a), indicating an aggregation of nPS (Fig. S4b).

Figure 6.

The organs (stomach and intestines) and their contents (a) of Zacco temminckii exposed through the diet to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS; green emissions) and the fluorescence of nPS in the organ contents (b,c). Red fluorescence is auto-fluorescence of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and green fluorescence is that of nPS. Scale bar = 1 cm (a) and 20 μm (b,c).

Toxic effects of nPS on test species

The results of individual toxicity tests on C. reinhardtii and D. magna are shown in Fig. S2. There was little or no mortality or effective toxicity on C. reinhardtii (Fig. S5a) and D. magna (Fig. S5b) in the range of tested concentrations for 72 h and 48 h, respectively (p > 0.05).

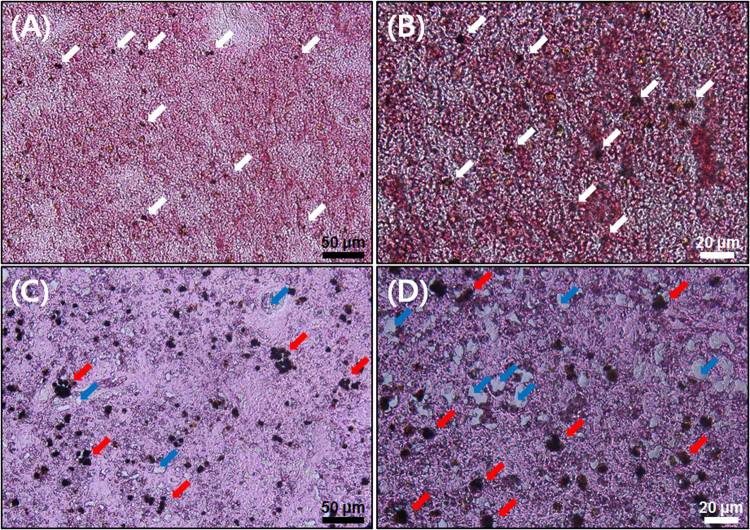

However, nPS caused several abnormalities in both O. sinensis and Z. temminckii after direct exposure for 7 d. First, livers from non-exposed and exposed Z. temminckii showed different histological patterns (Fig. 7). The livers from the control group had regularly distributed stained dark nuclei (Fig. 7a,b), but the livers of the exposed group had aggregated and agglomerated nuclei (Fig. 7c,d). This finding indicates that cells in liver tissues from exposed Z. temminckii were broken and destroyed. There were also several vacuoles in the liver tissues of exposed Z. temminckii. Synthetically, direct exposure of Z. temminckii to nPS for 7 d caused structural and histopathological problems. There was a slight increase in the total amount of cholesterol in the blood serum of exposed Z. temminckii compared with non-exposed fish (Fig. S6). There were slight increases of total cholesterol in nPS-exposed fish, but because there were insufficient replicates, these data could not be statistically analyzed.

Figure 7.

H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) stained liver tissues from Zacco temminckii not exposed (a,b) and exposed (c,d) to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS). Normal nuclei (white arrow), damaged and aggregated nuclei (red arrow), and vacuole (blue arrows) in liver tissue. Scale bar = 50 (black) and 20 (white) μm.

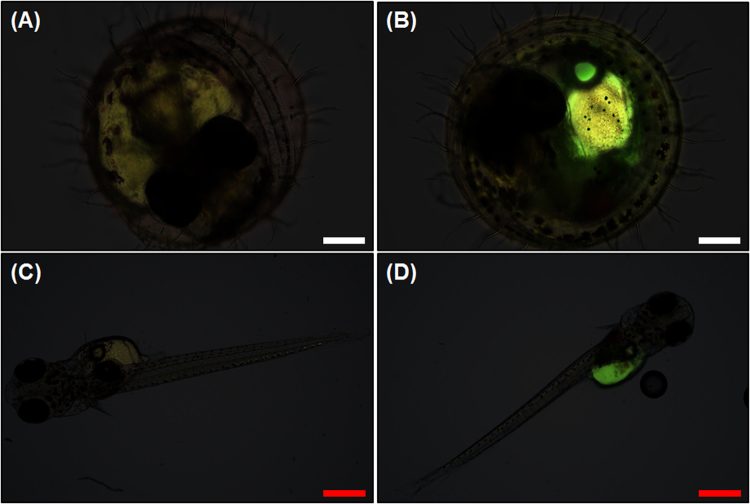

When embryos were directly exposed to 5 mg/L nPS, the same concentration to which adult O. sinensis were exposed, they showed bright green fluorescence, as did the yolk sacs of exposed embryos (Fig. 8). Compared with the embryos (Fig. 8a) and hatched juveniles (0 d) (Fig. 8c) from the control group, nPS-exposed embryos (Fig. 8b) and juveniles (0 d) (Fig. 8d) showed clear nPS fluorescence in the yolk sac.

Figure 8.

Merged (bright field and fluorescence) images of embryos and juveniles of Oryzias sinensis that were not exposed (a,c) and that were exposed (b,d) to nano-sized polystyrene (nPS). The embryos are 144 hours post fertilization (hpf) and juveniles are observed <24 h after hatching. The bright green fluorescence (b,d) indicates the uptake of nPS in organisms. Scale bar = 200 (a,b, white) and 500 (c,d, red) μm.

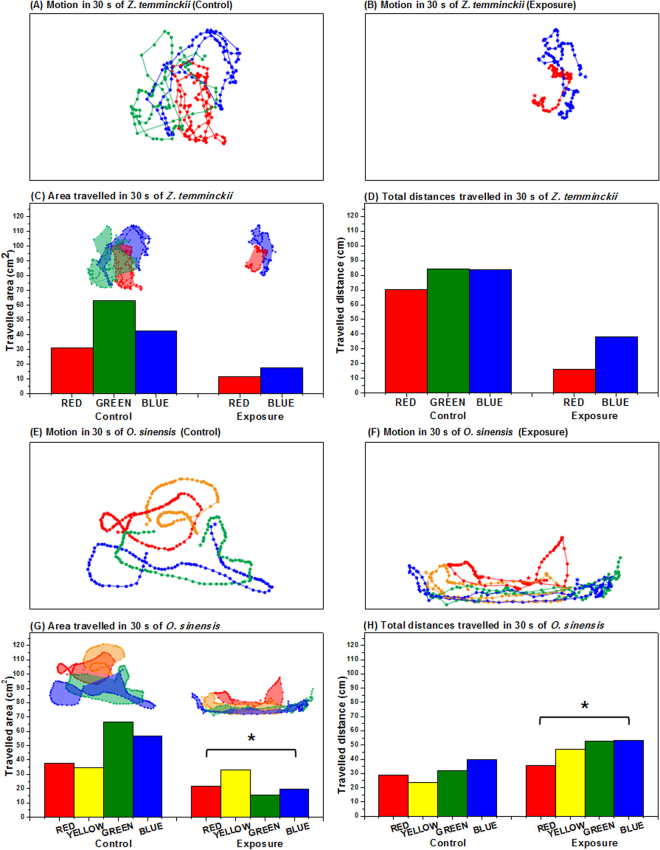

In addition, locomotive activities of O. sinensis and Z. temminckii were affected by nPS exposure (Fig. 9). The area through which fish traveled was significantly smaller in the nPS-exposed groups of both fish species (Fig. 9c,g). Total distances traveled in 30 s were significantly shorter in nPS-exposed Z. temminckii (Fig. 9d), whereas in nPS-exposed O. sinensis, they were slightly longer (p < 0.05) (Fig. 9h). These differences may be due to different swimming patterns between the two test species. Comparisons of free-swimming patterns and distances between individuals in the control group (Fig. 9a,e) showed that nPS-exposed fish maintained shorter distances between each individual and swam in shoals (Fig. 9b,f).

Figure 9.

The locomotive activities of Zacco temminckii (a–d) and Oryzias sinensis (e–h). Each bar in graphs shows the activity of one individual. Motion was recorded for 30 s of Z. temminckii not exposed to nPS (a) and exposed to 5 mg/L nano-sized polystyrene (nPS) (b). Quantitative data of the area traveled (c) and the total distances covered (d) for 30 s of nPS non-exposed and exposed Z. temminckii. Motion of O. sinensis not exposed (e) and exposed to nPS (f) was recorded for 30 s. Quantitative data of the area traveled (g) and the total distances covered (h) for 30 s of O. sinensis not exposed and exposed to nPS (p < 0.05). Different colors in each box designate different individuals, and the dots and the lines represent the locations for every 0.3 s and the movements of each individual, respectively.

Discussion

We investigated various negative effects of nPS on freshwater species and confirmed that nPS can induce disturbances in the morphology of liver tissue, lipid metabolism, embryos, and locomotive activities of fish. These results lead us to conclude that nanoplastics have adverse effects on aquatic organisms and induce biochemical, behavioral, and histological changes. Several previous studies have assessed the histopathological changes in the livers of fish fed micro- or nanoplastics. Rochman et al.53 and Lu et al.54 also confirmed that plastic particles can change and disturb liver morphology and induce histopathological changes in the liver tissue. These results indicate that nanoplastics might act as contaminants or pollutants in the bodies of fish and accumulate in the liver, the organ that detoxifies the body. Von Moos et al.31 confirmed disturbances of lipid metabolism in mussels exposed to microplastics, and Cedervall et al.46 investigated metabolic (cholesterol) changes in Carassius carassius exposed to nPS through their diet. Similarly, in the present study, we analyzed the differences in the total amount of cholesterol between control fish and nPS-exposed fish but could not carry out the statistical analysis because there were too few replicates. However, we confirmed that total cholesterol in fish slightly increased after nPS exposure. These results suggest that long-term exposure to nanoplastics may cause nutritional and health problems in fish and other organisms. Regarding exposure to embryos, Manabe et al.55 also observed bright green fluorescence in embryos exposed to fluorescent latex particles with a diameter of 50 nm. In another study, fluorescent nPS (diameters of 40 and 50 nm) entered the embryos of sea urchins14. Lee et al.56 confirmed that the pore size of embryo chorions of zebrafish was 0.5–0.7 μm, which is much larger than the diameter of nPS used in the present study. Although the test species that we used was O. sinensis, previous research can still be applicable. The results of previous studies, combined with our results, indicate that small plastics with nano-sized diameters can penetrate the walls of embryos and accumulate in the lipid of embryos due to the hydrophobic property of nanoplastics, the porous membranes of embryos, and material exchanges between organisms and environments. Mattsson et al.51 reported that nPS-exposed fish occupied less space in aquaria than non-exposed fish. Cedervall et al.46 observed that nPS-exposed fish moved more slowly than control fish and attributed it to nPS transfer from food to several organs, including the brain, via the bloodstream. These transferred nano-sized particles can cause biochemical changes in the brain, which leads to behavioral changes in fish, as noted in the present study. The brains of fish directly exposed to nPS in the present study could also have been affected, causing changes in their activities and behaviors. These behavioral changes include reduced feeding activity or vitality of individuals46,51, which can inhibit growth and reproduction. Reduced ability to avoid other predators is also a serious problem that can affect the health of natural ecosystems, ecosystem services, and productivity of fisheries51.

In this study, we exposed algae (C. reinhardtii) and water fleas (D. magna) to higher nPS concentrations than those encountered in a natural environment, to assess the effects of nPS on freshwater organisms. High concentration levels were also used in the trophic transfer experiment, for indisputable visual confirmation of nPS transfer to organisms. The extremely high concentrations used in the dose-response and trophic transfer experiments rarely exist in real environmental conditions57. However, to evaluate and assess the potential impact of nanoplastics and the reaction of organisms to them, these types of experiments are needed, although the results should be considered with caution. Nevertheless, in the natural environment, organisms might be exposed to low concentrations of nanoplastics for a long time; thus, there is the potential for cumulative build-up in their bodies. Future studies should also consider, and attempt to simulate real environmental conditions to elucidate the present-day impact of nanoplastics in the environment58.

Additionally, because these small plastics reached a high level in the food chain, it is possible that nPS can be transferred to consumers at an even higher trophic level, like humans, through their diet. Additional studies on acute and chronic toxicity of micro- and nanoplastics are underway to investigate various effects and mechanisms. The acute and chronic toxicity of micro- and nanoplastics also require further study.

Methods

nPS

Fluorescent nPS (10 mg/mL) was purchased from Bangs Laboratories, Inc. (Fishers, IN, USA). According to the manufacturer, these fluorescent microspheres have a 480-nm excitation and 520-nm emission wavelength and a mean diameter of 51 nm. The stock solution (% in product) contained water (≥89.81%), polystyrene (≤10%), surfactant (≤0.1%), and sodium azide (≤0.09%). ζ-potentials and hydrodynamic diameter of nPS were measured via the dynamic light-scattering technique (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, UK) in distilled water (DW), moderately hard water (MHW; combinations of magnesium sulfate, sodium bicarbonate, potassium chloride, and hydrated calcium sulfate)59, and tris-acetate-phosphate medium (TAP; combinations of TAP salts, phosphate solution, and Hunter’s trace elements: zinc, boron, manganese, cobalt, copper, molybdenum, and iron)60. We identified the surface charges, conditions, and status of nPS in each medium and confirmed which nPS properties remained the same in different media for storage, cultivation, and testing. In addition, nPS particles were observed using a high resolution scanning electron microscope (HR-SEM; SU 70, Horiba, Kyoto, Japan).

Test species

Trophic transfer was explored in a four-species freshwater ecosystem food chain consisting of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Daphnia magna, Oryzias sinensis, and Zacco temminckii. C. reinhardtii (UTEX, USA), a freshwater green alga with two flagella, was the primary producer in this experimental system. The cell size of C. reinhardtii was 2–20 μm. D. magna, a water flea that is the typical test species in ecotoxicity tests, was the primary consumer in this food chain. The body size of the neonate was 1.2–1.6 mm. O. sinensis, the Chinese rice fish, belongs to the same genus as the Japanese rice fish O. latipes, and has a body size of 25–30 mm. It was the secondary consumer in this food chain. Z. temminckii (dark chub), a large fish with a body size of 130–150 mm, was used as the end consumer. C. reinhardtii and D. magna were incubated in TAP (pH 7.1 ± 0.0) in a shaking incubator (24 ± 1 °C) and in MHW (pH 7.6 ± 0.3) in an incubator (21 ± 1 °C), respectively. Both incubators used a photoperiod of 16:8 h (light:dark). O. sinensis and Z. temminckii were purchased from an aquarium and fishery, respectively, and were acclimated in dechlorinated tap water for 2–4 weeks in the laboratory before the test. All experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations for ethical incubation, experimental use, and euthanasia of test animals, and all experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Konkuk University, under authorization code number KU16096.

Trophic transfer of nPS from C. reinhardtii to Z. temminckii

A total of three trophic transfer assays (C. reinhardtii → D. magna, 300 control-group and 300 exposed D. magna; C. reinhardtii → D. magna → O. sinensis, 30 control-group and 30 exposed O. sinensis; and C. reinhardtii → D. magna → O. sinensis → Z. temminckii, three control-group and three exposed Z. temminckii) were conducted, spanning a week, and the experiment was carried out three times (triplicate). Every fish in the test was visually observed and 10 D. magna in each treatment were observed. First, 1 mL of 1 × 107 cells/mL C. reinhardtii was exposed to 50 mg/L nPS in a 1.75-mL test tube in an end-over-end rotator (LNS-MP8; Daihan Science, Korea) at 24 °C, with a 16:8 h (light:dark) photoperiod for 72 h. After this direct exposure, 1 mL of C. reinhardtii was washed with DW at 5,000 rpm for 1 min and then added to 50 mL of MHW in an 85-mL flat-bottomed glass vial (internal diameter, 40 mm; length, 75 mm) containing 100 neonates (<24 h) of D. magna for 5 h. Next, all alga-fed D. magna were collected and washed with MHW once, to remove adhered nPS. The D. magna were fed to 10 O. sinensis in 8 L of dechlorinated tap water in a glass tank (width, 0.2 m; length, 0.2 m; height, 0.25 m). These feedings occurred twice during 48 h. Finally, 10 O. sinensis that had been fed contaminated D. magna were washed with dechlorinated tap water and fed to a single Z. temminckii in 30 L of dechlorinated tap water in a plastic tank (width, 0.6 m; length, 0.4 m; height, 0.21 m). This feeding occurred once in a 24-h period, with four replicates.

Following trophic transfer tests, C. reinhardtii and D. magna were observed using an optical microscope (Olympus BX 51; Olympus, Japan) equipped with a fluorescent filter (excitation wavelength, 460–495 nm; emission wavelength, 510 nm; U-MWIB3; Olympus Cooperation, Tokyo, Japan). The green emission of nPS was observed, separated from the red emission of algal auto-fluorescence. Next, CLSM was used to observe control and exposed C. reinhardtii (LSM710; Carl Zeiss, Germany) and D. magna (FV-1000 spectral; Olympus, Japan). Confocal images of nPS attached to the surface of C. reinhardtii and within the guts of D. magna and Z-stack images (stacks of multiple images taken at different focal lengths) were analyzed. Z-stack images of C. reinhardtii were taken under specific conditions: entire depth 49 μm; 49 total images; each sheet 1 μm thick. Images of D. magna were taken under specific conditions: entire depth 236 μm; 236 total images; each sheet 1 μm thick. In addition, the gastrointestinal tract and microvilli of controlled and exposed D. magna were observed using a Bio-TEM (Tecnai G2SpiritTwin; FEI, USA) to confirm the effect of nPS on the organs.

O. sinensis and Z. temminckii exposed through the diet to nPS were also analyzed via an optical microscope with a fluorescent filter. O. sinensis and Z. temminckii were anesthetized and the intestines were removed. Because of the physical size and thickness of the fish, the digestive organs were extracted and the organs and contents were observed under the microscope. The intestines of O. sinensis were observed via CLSM (LSM710; Carl Zeiss, Germany) to determine whether nPS was present in the inner part of the organ. The Z-stack images of O. sinensis were taken under specific conditions: entire depth 219 μm; 219 total images; each sheet 1 μm thick. The excitation wavelengths of the CLSM laser were 488 and 543 nm for nPS fluorescence and for auto-fluorescence of algae, respectively. Unfortunately, the digestive organs of Z. temminckii could not be observed directly under the microscope because of their thickness and opacity. Instead, we dissected the organs, collected the inner contents of the intestine and stomach, and observed them via microscope to determine the amount of nPS transferred via the diet.

Direct exposure of test species to nPS

We carried out individual toxicity tests of nPS on C. reinhardtii and D. magna using modified Test Guidelines No. 20161 and No. 20262, respectively, of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The detailed protocol was adapted from Chae and An63. C. reinhardtii was exposed to a maximum 100 mg/L nPS (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mg/L), and D. magna was exposed to a maximum 10 mg/L nPS (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/L). After exposure, chlorophyll fluorescence of C. reinhardtii was measured via a fluorescence microplate reader (GeminiEM; Molecular Devices, USA). The mortality and immobilization of D. magna were quantified at 24 and 48 h.

The direct exposure experiments on O. sinensis and Z. temminckii were carried out once. A total of eight O. sinensis (including embryos that hatched during the experiment) and three Z. temminckii were exposed to nPS at 5 mg/L in aerated glass tanks individually (one Z. temminckii in the exposed group escaped from the glass tank and died). Liver histopathology, the amount of cholesterol in blood serum, embryonic uptake, and locomotive activity were analyzed. After 7 d of exposure, the livers of Z. temminckii were extracted and liver histopathology was analyzed after dehydrating, sectioning, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining the nuclei of cells (acidic, negatively charged) and other structures (positively charged amino acid side chains). The cholesterol contents in the blood serum of Z. temminckii were also investigated using an HDL and LDL/VLDL cholesterol assay kit (Catalog # ab65390, Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

O. sinensis spawned during the exposure and the fertilized eggs were exposed to nPS for 24 h. The eggs were then transferred into an embryo-rearing solution and incubated at room temperature for microscopic analysis. Embryonic uptake in O. sinensis was observed, using an optical microscope equipped with a fluorescent filter, 5 d after transfer.

The locomotive activities of both O. sinensis and Z. temminckii were observed in a tank (30 cm wide × 20 cm long × 20 cm tall) containing 10 L dechlorinated water. Non-exposed and exposed fish were placed in tanks containing clean tap water but no food (four control O. sinensis, four exposed O. sinensis, three control Z. temminckii, and two exposed Z. temminckii in each tank). After allowing 5 min for acclimation, their activities were recorded using a digital camera. The videos were recorded for 30 s with images captured at 0.3-s intervals. These 100 images were merged and analyzed by placing dots on the captured images via Adobe Photoshop, and the area and distances traveled were investigated using Image J (free software). Because of the small number of individuals, these recordings were considered pseudoreplication.

Statistical analysis

We statistically analyzed the results of individual toxicity tests of nPS on growth in C. reinhardtii, survival of D. magna, and behavior of O. sinensis (analysis on Z. temminckii was excluded because of the lack of replicates). To confirm the reliability of the data, we first checked its normal distribution and the homoscedasticity of its variance in Origin pro 8.0 (OriginLab Corp., MA, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Dunnett64 t-test (two-tailed post-hoc) for multiple comparisons was performed using EMSL Cincinnati Dunnett 1.5, to identify significant differences between the control and nPS-exposed groups. A 95% significance level (p < 0.05) was used for all comparisons.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (2016R1A2B3010445). We thank the Korean Basic Science Institute (KBSI) for their assistance with our dynamic light scattering and Bio-TEM analyses.

Author Contributions

Y.C. and Y.-J.A. conceived and designed the research. Y.C., D.K., and S.W.K. performed the experiments. Y.C. and S.W.K. analyzed the images and data. Y.C. and Y.-J.A. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-18849-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Thompson RC, et al. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science. 2004;304:838–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1094559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browne MA, Galloway T, Thompson R. Microplastic—an emerging contaminant of potential concern? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2007;3:559–561. doi: 10.1002/ieam.5630030412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browne MA, et al. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:9175–9179. doi: 10.1021/es201811s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rochman CM, Manzano C, Hentschel BT, Simonich SLM, Hoh E. Polystyrene plastic: a source and sink for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:13976–13984. doi: 10.1021/es403605f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C, Zhang K, Huang X, Liu J. Sorption of pharmaceuticals and personal care products to polyethylene debris. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23:8819–8826. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh B, Sharma N. Mechanistic implications of plastic degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008;93:561–584. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2007.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brine T, Thompson RC. Degradation of plastic carrier bags in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010;60:2279–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadri SS, Thompson RC. On the quantity and composition of floating plastic debris entering and leaving the Tamar Estuary, Southwest England. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;81:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imhof HK, Ivleva NP, Schmid J, Niessner R, Laforsch C. Contamination of beach sediments of a subalpine lake with microplastic particles. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:R867–R868. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksen M, et al. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013;77:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Free CM, et al. High-levels of microplastic pollution in a large, remote, mountain lake. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;85:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner M, et al. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: what we know and what we need to know. Env. Sci. Eur. 2014;26:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2190-4715-26-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo-Ruz V, Gutow L, Thompson RC, Thiel M. Microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:3060–3075. doi: 10.1021/es2031505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Della Torre C, et al. Accumulation and embryotoxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles at early stage of development of sea urchin embryos Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:12302–12311. doi: 10.1021/es502569w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter EJ, Anderson SJ, Harvey GR, Miklas HP, Peck BB. Polystyrene spherules in coastal waters. Science. 1972;178:749–750. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4062.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter EJ, Smith KL. Plastics on the Sargasso Sea surface. Science. 1972;175:1240–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4027.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colton JB, Burns BR, Knapp FD. Plastic particles in surface waters of the northwestern Atlantic. Science. 1974;185:491–497. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4150.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler CW. Marine debris and northern fur seals: a case study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1987;18:326–335. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(87)80020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frias JPGL, Sobral P, Ferreira AM. Organic pollutants in microplastics from two beaches of the Portuguese coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010;60:1988–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrady AL. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011;62:1596–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakashima E, Isobe A, Kako SI, Itai T, Takahashi S. Quantification of toxic metals derived from macroplastic litter on Ookushi Beach, Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:10099–10105. doi: 10.1021/es301362g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, et al. Relationships among the abundances of plastic debris in different size classes on beaches in South Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013;77:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nor NHM, Obbard JP. Microplastics in Singapore’s coastal mangrove ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;79:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Cauwenberghe L, Janssen CR. Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2014;193:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fossi MC, et al. Are baleen whales exposed to the threat of microplastics? A case study of the Mediterranean fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012;64:2374–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foekema EM, et al. Plastic in north sea fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:8818–8824. doi: 10.1021/es400931b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Witte B, et al. Quality assessment of the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis): Comparison between commercial and wild types. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014;85:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fossi MC, et al. Large filter feeding marine organisms as indicators of microplastic in the pelagic environment: The case studies of the Mediterranean basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Mar. Environ. Res. 2014;100:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima ARA, Costa MF, Barletta M. Distribution patterns of microplastics within the plankton of a tropical estuary. Environ. Res. 2014;132:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Besseling E, et al. Microplastic in a macro filter feeder: humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015;95:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Moos N, Burkhardt-Holm P, Köhler A. Uptake and effects of microplastics on cells and tissue of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis L. after an experimental exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:11327–11335. doi: 10.1021/es302332w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besseling E, Wegner A, Foekema EM, Van Den Heuvel-Greve MJ, Koelmans AA. Effects of microplastic on fitness and PCB bioaccumulation by the lugworm Arenicola marina (L.) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:593–600. doi: 10.1021/es302763x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole M, et al. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:6646–6655. doi: 10.1021/es400663f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee KW, Shim WJ, Kwon OY, Kang JH. Size-dependent effects of micro polystyrene particles in the marine copepod Tigriopus japonicus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:11278–11283. doi: 10.1021/es401932b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliveira M, Ribeiro A, Hylland K, Guilhermino L. Single and combined effects of microplastics and pyrene on juveniles (0+group) of the common goby Pomatoschistus microps (Teleostei, Gobiidae) Ecol. Indic. 2013;34:641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Besseling E, Wang B, Lürling M, Koelmans AA. Nanoplastic affects growth of S. obliquus and reproduction of D. magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:12336–12343. doi: 10.1021/es503001d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Au SY, Bruce TF, Bridges WC, Klaine SJ. Responses of Hyalella azteca to acute and chronic microplastic exposures. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015;34:2564–2572. doi: 10.1002/etc.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole M, Lindeque P, Fileman E, Halsband C, Galloway TS. The impact of polystyrene microplastics on feeding, function and fecundity in the marine copepod Calanus helgolandicus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:1130–1137. doi: 10.1021/es504525u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan FR, Syberg K, Shashoua Y, Bury NR. Influence of polyethylene microplastic beads on the uptake and localization of silver in zebrafish (Danio rerio) Environ. Pollut. 2015;206:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes LA, Turner A, Thompson RC. Adsorption of trace metals to plastic resin pellets in the marine environment. Environ. Pollut. 2012;160:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rochman CM, Hoh E, Hentschel BT, Kaye S. Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants to five types of plastic pellets: implications for plastic marine debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:1646–1654. doi: 10.1021/es303700s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee H, Shim WJ, Kwon JH. Sorption capacity of plastic debris for hydrophobic organic chemicals. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;470:1545–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang F, Shih KM, Li XY. The partition behavior of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanesulfonamide (FOSA) on microplastics. Chemosphere. 2015;119:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong SH, Shim WJ, Hong L. Methods of analysing chemicals associated with microplastics: a review. Anal. Methods. 2017;9:1361–1368. doi: 10.1039/C6AY02971J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rani M, et al. Benzotriazole-type ultraviolet stabilizers and antioxidants in plastic marine debris and their new products. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;579:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cedervall T, Hansson LA, Lard M, Frohm B, Linse S. Food chain transport of nanoparticles affects behaviour and fat metabolism in fish. PloS One. 2012;7:e32254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bejgarn S, MacLeod M, Bogdal C, Breitholtz M. Toxicity of leachate from weathering plastics: An exploratory screening study with Nitocra spinipes. Chemosphere. 2015;132:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li HX, et al. Effects of toxic leachate from commercial plastics on larval survival and settlement of the barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:924–931. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandara e Silva PP, Nobre CR, Resaffe P, Pereira CDS, Gusmão F. Leachate from microplastics impairs larval development in brown mussels. Water Res. 2016;106:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farrell P, Nelson K. Trophic level transfer of microplastic: Mytilus edulis (L.) to Carcinus maenas (L.) Environ. Pollut. 2013;177:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mattsson K, et al. Altered behavior, physiology, and metabolism in fish exposed to polystyrene nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;49:553–561. doi: 10.1021/es5053655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Setälä O, Fleming-Lehtinen V, Lehtiniemi M. Ingestion and transfer of microplastics in the planktonic food web. Environ. Pollut. 2014;185:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rochman, C. M., Hoh, E., Kurobe, T. & Teh, S. J. Ingested plastic transfers hazardous chemicals to fish and induces hepatic stress. Sci. Rep. 3, 10.1038/srep03263 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Lu Y, et al. Uptake and accumulation of polystyrene microplastics in zebrafish (Danio rerio) and toxic effects in liver. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:4054–4060. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manabe M, Tatarazako N, Kinoshita M. Uptake, excretion and toxicity of nano-sized latex particles on medaka (Oryzias latipes) embryos and larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011;105:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee KJ, Nallathamby PD, Browning LM, Osgood CJ, Xu XHN. In vivo imaging of transport and biocompatibility of single silver nanoparticles in early development of zebrafish embryos. ACS Nano. 2007;1:133. doi: 10.1021/nn700048y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chae Y, An YJ. Effects of micro-and nanoplastics on aquatic ecosystems: Current research trends and perspectives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017;124:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lenz R, Enders K, Nielsen TG. Microplastic exposure studies should be environmentally realistic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E4121–E4122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606615113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.U.S. EPA. Short-term Methods for Estimating the Chronic Toxicity of Effluents and Receiving Waters to Freshwater Organisms. EPA-821-R-02-013, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC20460 (2002).

- 60.Gorman DS, Levine RP. Cytochrome f and plastocyanin: their sequence in the photosynthetic electron transport chain of Chlamydomonas reinhardi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1965;54:1665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.6.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Guideline for Testing of Chemicals No. 201. In Freshwater Alga and Cyanobacteria, Growth Inhibition Test. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (2006).

- 62.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Guideline for Testing of Chemicals No. 202. Daphnia sp., Acute Immobilisation Test. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (2004).

- 63.Chae Y, An Y-J. Toxicity and transfer of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanowires in an aquatic food chain consisting of algae, water fleas, and zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016;173:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunnett CW. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1955.10501294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.