Abstract

Background

In 2011 and again in 2016, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) asked all European countries to carry out nationwide studies on the prevalence of nosocomial infection (NI) and antibiotic use (AU). Data on NI and AU constitute an essential basis for the development of measures to prevent infection and lessen antibiotic resistance.

Methods

The German prevalence study of 2016 was carried out according to the ECDC protocol. Alongside a sample of 49 acute-care hospitals requested by the ECDC that was representative in terms of size (number of beds), further hospitals were invited to participate as well. Analyses were made of the overall group (218 hospitals, 64 412 patients), the representative group (49 hospitals), and the core group (46 hospitals). The core group consisted of the hospitals that had participated in the study of 2011.

Results

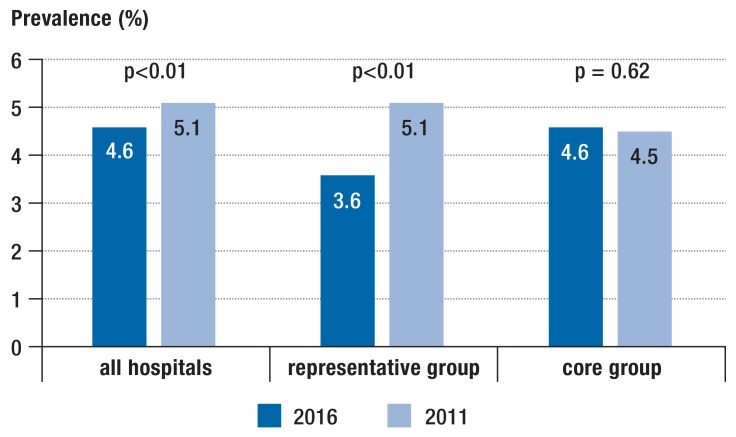

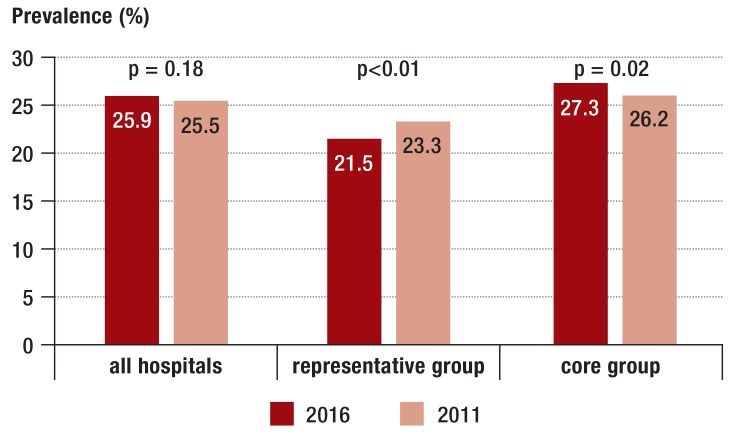

The prevalence of patients with NI was 4.6% in the overall group in 2016; it had been 5.1% in 2011 (p <0.01). In the representative group, the prevalence was 3.6% (compared to 5.1% in 2011, p <0.01). In the core group, the prevalence of NI was the same in 2016 as it had been in 2011. The prevalence of patients with ABU in the overall group remained the same, but a fall was seen in the representative group (21.5% versus 23.3%; p <0.01) and a rise in the core group (27.3% versus 26.2%; p = 0.02). The staff–patient ratio among the infection prevention and control professionals improved in all three groups.

Conclusion

A decrease in NI and AU prevalence was seen in the representative group, while mixed results were seen in the other analyzed groups. Further efforts to reduce NI and ABA are clearly necessary.

In 2011 and 2012, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) urged all European countries to conduct national point prevalence surveys (PPS) on the occurrence of nosocomial (healthcare-associated) infections (NI) and antibiotic use (AU) in hospitals, using set standard protocols (1). Altogether 29 countries of the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA) as well as Croatia participated in this survey of 1149 acute-care hospitals. The prevalence of patients acquiring at least one NI was 6.0% (95% confidence interval (CI): [5.7; 6.3%]), the prevalence of patients receiving at least one antimicrobial agent was 35%. The prevalence of NIs that started during the current hospital stay was 4.5%; the remaining NIs were already present on admission to the hospital as the result of earlier treatment.

Based on these data, a method to convert prevalence data into incidence data and a systematic review on the burden of NIs, the ECDC estimated that annually more than 2.6 million new cases of NI occur in the EU and EEA. The cumulative burden of NI was estimated to be 501 disability-adjusted life years (DALY) per 100 000 population. This corresponds to 2 million years of life lost due to premature death and altogether 681 400 years during which the patients had to live with infection-related disabilities (2).

Five years later, the ECDC again called upon all European countries to conduct national prevalence surveys, using ECDC protocols and definitions. In Germany, the National Reference Center for the Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections which had been commissioned with the conduct of the previous study in 2011 was once again selected to conduct the national prevalence survey (3, 4).

In the period between the two national prevalence studies, NI and AU in German hospitals were topics that attracted considerable attention. In 2011, the German Infection Protection Act (IfSG) was amended; subsequently, all German Federal States revised their State Hygiene Regulations or adopted such regulations for the first time. Consequently, the results of the new national prevalence survey provide an opportunity to assess whether the high level of attention devoted to this issue has in the meantime helped to improve the situation.

Methods

The standard protocol issued by the ECDC was translated into German and used for the prevalence survey (5). In February 2015, the ECDC once again urged all countries to invite a representative sample of hospitals to participate in the survey. Taking into account the population size and hospital structure in Germany, 49 hospitals were to be selected. On the basis of the 2013 Directory of German Hospitals (DKV, Deutsches Krankenhausverzeichnis), a random sample of hospitals was selected taking into account the respective number of hospital beds (including two replacement hospitals); subsequently, the selected hospitals were invited to participate in the survey. In addition, all 1462 (as of 1st quarter 2016) hospitals participating in the Hospital Infection Surveillance System (KISS, Krankenhaus-Infektions-Surveillance-System) were invited to participate in the prevalence survey. If any of the hospitals selected for the representative sample (including replacement hospitals) was not interested in participating in the survey, a hospital from the group of hospitals not included in the representative sample with a matching number of hospital beds was invited instead.

The primary endpoints of the study were the overall prevalence of NI and the prevalence of AU. The secondary endpoint was the prevalence of NI which occurred in the respective hospital, i.e. which were not already present on admission to hospital as the result of previous medical treatments. For the survey, the ECDC�s definitions of NI were used, as described in the PPS protocol (6). Only infections which were active or treated with antimicrobial agents on the day of the survey were included. For antibiotic use documentation, the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System of the World Health Organization (WHO) was used (7).

In seven introductory courses held nationwide, staff members of the participating hospitals were familiarized with the survey protocol and the definitions used. The survey was conducted from May to June 2016. Trained hospital staff members successively visited the wards of their respective hospital to collect relevant data. Data were obtained from patient records and, if necessary, ward staff was interviewed to provide missing information. For any identified NI, data on the type and start of infection as well as infection-related microbiological data were collected. Furthermore, it was documented whether the patient had already contracted the nosocomial infection in another hospital prior to admission or acquired it during the current hospital stay. With regard to AU, the type of antimicrobial agent, route of administration and indication were documented and it was checked whether the indication was documented in the patient records. All tasks regarding data search and data collection from patients of a single ward had to be completed in one day.

Furthermore, each hospital had to complete a data sheet on the hospital�s structural and process quality, including number of hospital beds, number of infection prevention and control nurses, and infection prevention and control doctors as well as consumption of hand rub per patient day.

Data were entered into a web-based software and validated. Analyses were performed in the National Reference Center. First, the 2011 and 2016 results for all participating hospitals were compared regarding the prevalence of all patients with NI and regarding the antibiotic use. In addition, the representative samples in the various surveys were compared with each other. Moreover, the prevalence rates for a core group of hospitals that participated in both the 2011 and 2016 surveys were analyzed. For the comparison of the 2011 and 2016 prevalence rates, the chi-square test was used; other parameters were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Further information, such as prevalence rates of the various NIs, type of microbial agent, and class of antibiotics were only analyzed for the total group of participating hospitals. For the analyses, the statistical software R and the OpenEpi software were used.

Results

Altogether 218 hospitals with 64 412 included patients participated in the 2016 survey. This corresponds to 11.4% of the 1911 hospitals listed in the Directory of German Hospitals (DKV) in 2013 (8). Of these hospitals, 49 were included in the representative sample reported to ECDC. Most participating hospitals (54%) are responsible for the provision of standard care, 29% provide tertiary care or specialist care and 36 hospitals (17%) offer maximum care, including 7 university hospitals.

Table 1 and eTable 1 summarize key hospital parameters and the results for the 3 selected endpoints for all participating hospitals, the representative sample and the core group. While the median number of hospital beds in the overall group of participating hospitals decreased (305 in 2016 versus 359 beds in 2011), the median hospital bed number in 2016 in the representative sample was 205 and in the core group 392 beds. The median length of hospital stay decreased in the overall group between 2011 and 2016 from 6.6 to 6.3 inpatient days. Furthermore, employment of infection prevention and control nurses, and infection prevention and control doctors increased significantly in all 3 analyzed groups. The consumption of hand rub per patient day as a surrogate parameter of hand hygiene increased in the overall group (from median 24.5 mL to median 32.5 mL per patient day).

Table 1. Characteristics of hospitals, prevalence of nosocomial infections and antibiotic use*3.

| Parameter | Year 2016 | Year 2011 | p value |

| Number of hospitals | 218 | 132 | |

| Number of hospital beds: median (IQR) | 305 (185–541) | 359 (183–607) | 0.17*1 |

| Length of hospital stay: median in days (IQR) | 6.3 (5.5–7.3) | 6.6 (6.0–8.0) | <0.01*1 |

| Number of patients | 64 412 | 41 539 | |

| Beds per full-time IPC nurse: median (IQR) | 203 (172–257) | 354 (278–460) | <0.01*1 |

| Beds per full-time IPC doctor: median (IQR) | 817 (513–1562) | 1570 (852–3663) | <0.01*1 |

| Alcohol hand rub consumption in mL per patient day: median (IQR) | 32.5 (25.0–51.4) | 24.5 (17.6–38.1) | <0.01*1 |

| Prevalence of all patients with NI: %, 95% CI | 4.58 [4.42; 4.75] | 5.08 [4.87; 5.29] | <0.01*2 |

| Prevalence of patients with NI acquired during current hospital stay: %, 95% CI | 3.32 [3.18; 3.46] | 3.76 [3.57; 3.94] | <0.01*2 |

| Prevalence of patients with AU: %, 95% CI | 25.9 [25.6; 26.3] | 25.5 [25.1; 26.0] | 0.18*2 |

*1 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate p values.

*2 The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate the p valuest.

*3 This table contains the data of all participating hospitals.

AU, antibiotic use; CI, confidence interval; NI, nosocomial infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; IQR, interquartile range

eTable 1. Characteristics of the representative hospitals and core group hospitals, prevalence of nosocomial infections and antibiotic use.

| Group | Parameter | Year 2016 | Year 2011 | p value |

| Number | 49 | 46 | ||

| Representative sample | Number of hospital beds: median (IQR) | 205 (102–450) | 216 (121–362) | 0.97*1 |

| Length of hospital stay: median in days (IQR) | 6.4 (5.6–8.7) | 6.4 (5.6–7.3) | 0.77*1 | |

| Number of patients | 11 324 | 9 626 | ||

| Beds per full-time IPC nurse: median (IQR) | 203 (167–280) | 388 (287–531) | <0.01*1 | |

| Beds per full-time IPC doctor: ‧median (IQR) | 670 (468–1168) | 1580 (1 095–3 358) | 0.01*1 | |

| Alcohol hand rub use in mL per patient day: median (IQR) | 24.1 (17.8–35.3) | 19.7 (16.3–30.0) | 0.40*1 | |

| Prevalence of all patients with NI: %, 95% CI | 3.61 [3.28; 3.97] | 5.07 [4.64; 5.53] | <0.01*2 | |

| Prevalence of patients with NI acquired during current hospital stay: %, 95% CI | 2.53 [2.25; 2.84] | 3.37 [3.01; 3.75] | <0.01*2 | |

| Prevalence of patients with AU: %, 95% CI | 21.5 [20.8; 22.3] | 23.3 [22.5; 24.2] | <0.01*2 | |

| Number | 46 | 46 | ||

| Core group | Number of hospital beds: median (IQR) | 392 (231–614) | 368 (270–665) | 0.86*1 |

| Length of hospital stay: median in days (IQR) | 6.0 (5.3–7.0) | 6.6 (5.9–8.0) | <0.01*1 | |

| Number of patients | 17 462 | 17 009 | ||

| Beds per full-time IPC nurse: median (IQR) | 192 (173–255) | 354 (280–430) | <0.01*1 | |

| Beds per full-time IPC doctor: ‧median (IQR) | 786 (517–1495) | 2674 (1 698–4 195) | <0.01*1 | |

| Alcohol hand rub consumption in mL per patient day: median (IQR) | 33.7 (29.2–45.0) | 28.3 (18.6–38.3) | 0.34*1 | |

| Prevalence of all patients with NI: %, 95% CI | 4.62 [4.31; 4.94] | 4.53 [4.22; 4.85] | 0.62*2 | |

| Prevalence of patients with NI acquired during current hospital stay: %, 95% CI | 3.51 [3.24; 3.79] | 3.64 [3.36; 3.93] | 0.52*2 | |

| Prevalence of patients with AU: %, 95% CI | 27.3 [26.6; 28.0] | 26.2 [25.5; 26.8] | 0.02*2 |

*1 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the p values.

*2 The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate these p values.

AU, antibiotic use; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; IPC, infection prevention and control; NI, nosocomial infection

In all 218 hospitals, the number of patients with NI decreased by about 10% from 5.1% to 4.6% (p<0.01) (figure 1). Likewise, a decrease was overserved in the representative group of hospitals, but not in the core group. In the overall group, 72.6% of NIs occurred during the current hospital stay (table 1). Such NIs decreased from 3.8% to 3.3% in all participating hospitals and from 3.4% to 2.5% in the representative sample, but again not in the core group (etable 1). In contrast to the development of NIs, the prevalence of patients with AU remained unchanged: In 2016, the prevalence of AU was 25.9% compared to 25.5% in 2011. However, a decrease in the representative sample and an increase in the core group was noted (eTable 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (%) of patients with nosocomial infections

The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate the p values.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of patients with antibiotic use

The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate the p values.

Altogether 3104 nosocomial infections were diagnosed in 2951 patients. Lower respiratory tract infections, postoperative surgical site infections and urinary tract infections continue to be the most common NIs, each accounting for about one quarter of all NIs; here, a decrease in postoperative surgical site infections and urinary tract infections was noted. By contrast, the prevalence of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) increased compared to 2011 (table 2).

Table 2. The 5 most common nosocomial infections in all participating hospitals (comparison 2016 versus 2011).

| Type of infection |

NI prevalence 2016 (%, 95% CI) |

Proportion NI 2016 (%) (n = 3104) |

NI prevalence 2011 (%, 95-%-KI) |

Proportion NI 2011 (%) (n = 2248) |

p value, refering to NI prevalence |

| Lower respiratory infections | 1.16 [1.07; 1.24] | 24 | 1.17 [1.06; 1.27] | 21.7 | 0.96 |

| Surgical site infections | 1.08 [1.00; 1.16] | 22.4 | 1.31 [1.20; 1.42] | 24.3 | <0.01 |

| Urinary tract infections | 1.04 [0.96; 1.12] | 21.6 | 1.26 [1.15; 1.37] | 23.2 | <0.01 |

| Clostridium difficile infections | 0.48 [0.43; 0.54] | 10 | 0.34 [0.29; 0.41] | 6.4 | <0.01 |

| Primary sepsis | 0.24 [0.21; 0.28] | 5.1 | 0.26 [0.21; 0.31] | 5.7 | 0.68 |

| other infections | n.r. | 16.9 | n.r. | 18.7 | n.r. |

The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate the p values.

CI, confidence interval; NI, nosocomial infections; n.r., non-relevant

In intensive care units, the prevalence of patients with NIs was 17.1% and thus more the four times as high as in non-intensive care wards (3.8%). Altogether, 52.0% of intensive care patients compared to 24.4% of non-intensive care patients received antibiotic treatment on the day of data collection.

In 58.5% of NIs, microbiological identification of the pathogen was available at the time of the prevalence survey. In 2011, it were 55.0%. If on the day of the survey, samples had already been obtained for microbiological testing, but the results were not yet available, these results were not added later in order to limit the survey-related workload. Consequently, the overview of microbiological findings presented here is incomplete. Altogether, 2294 NI-causing pathogens were documented. The most common pathogens were Escherichia coli (16.6%), followed by Clostridium difficile (13.6%), Staphylococcus aureus (12.0%), Enterococcus faecalis (6.9%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5.8%). Compared to 2011, Clostridium difficile toppled Staphylococcus aureus from second place in the list of the most common NI pathogens.

Altogether 22 086 antibiotic treatments were documented in 16 688 patients. Among the indications for antibiotic use, the share of infections increased while the share of prophylactic use decreased (table 3). In line with the results of the 2011 survey, a high proportion of perioperative prophylaxis beyond the day of surgery was noted. With 31.3%, the proportion of patient records where the indication for antibiotic use was not documented was comparatively high. However, in most cases it was possible to find out about the indication from other sources, e.g. by making enquiries.

Table 3. Indications for antimicrobial use in patients receiving antibiotics on the day of the prevalence survey of all participating hospitals (comparison 2016 versus 2011).

| Reason for antibiotic use |

Patients with antibiotics 2016 (n = 16 688) |

Proportion of total administration of antibiotics 2016 (%) (n = 22 086) |

Prevalence 2016 (%) of patients receiving antibiotics (95% CI) |

Prevalence 2011 (%) of patients receiving antibiotics (95% CI) |

p value |

| Treatment | 12 046 | 73.0 | 18.7 [18.4; 19.0] | 16.9 [16.6; 17.3] | <0.01 |

| – of infections present on admission | 8889 | 53.0 | 13.8 [13.5; 14.1] | 12.4 [12.1; 12.7] | <0.01 |

| – of nosocomial infections | 3259 | 20.0 | 5.1 [4.9; 5.2] | 4.7 [4.5; 4.9] | <0.01 |

| Prophylaxis | 4032 | 21.7 | 6.3 [6.1; 6.5] | 8.0 [7.7; 8.2] | <0.01 |

| – non-surgical | 1185 | 6.8 | 1.8 [1.7; 1.9] | 2.5 [2.3; 2.6] | <0.01 |

| – perioperative | 2906 | 14.8 | 4.5 [4.4; 4.7] | 5.6 [5.3; 5.8] | <0.01 |

| – of these only single dose on day of surgery |

1186 | 5.7 | 1.8 [1.7; 1.9] | 1.4 [1.3; 1.5] | <0.01 |

| – of these multiple doses on the day of surgery |

163 | 0.7 | 0.3 [0.2; 0.3] | 0.4 [0.3; 0.4] | <0.01 |

| – of these beyond the day of surgery |

1557 | 8.3 | 2.4 [2.3; 2.5] | 3.8 [3.6; 4.0] | <0.01 |

| other/unknown indications | 961 | 5.4 | 1.5 [1.4; 1.6] | 1.2 [1.1; 1.3] | <0.01 |

The p value corresponds to prevalence and was calculated using the two-sided chi-square test.

CI, confidence interval

In the 2016 survey, the class of antibiotics most commonly used was penicillins with �-lactamase inhibitors (23.2%), followed by second-generation cephalosporins (12.9%), fluoroquinolones (11.3%), third-generation cephalosporins (8.9%), and carbapenems (6.2%) (table 4). Penicillins with �-lactamase inhibitors were used more frequently in 2016 compared to 2011, while second- and third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones were used less often. Second-generation cephalosporins were mainly used for perioperative prophylaxis. The percentage shares of the most commonly used classes of antibiotics are listed for treatment and prophylaxis in eTable 2.

Table 4. The 10 most common classes of antibiotics in all participating hospitals (comparison 2016 versus 2011).

| Class of antibiotics | Number 2016 |

Proportion 2016 (%, 95% CI) |

Number 2011 |

Proportion 2011 (%, 95% CI) |

p value |

| Penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors | 5119 | 23.2 [22.6; 23.8] | 1773 | 12.6 [12.1; 13.2] | <0.01 |

| Second-generation cephalosporins | 2856 | 12.9 [12.5; 13.4] | 2054 | 14.6 [14.0; 15.2] | <0.01 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 2494 | 11.3 [10.9; 11.7] | 1971 | 14.0 [13.4; 14.6] | <0.01 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | 1971 | 8.9 [8.6; 9.3] | 1498 | 10.6 [10.1; 11.2] | <0.01 |

| Carbapenems | 1369 | 6.2 [5.9; 6.5] | 825 | 5.9 [5.5; 6.3] | 0.19 |

| Imidazole derivatives | 1138 | 5.2 [4.8; 5.5] | 741 | 5.3 [4.9; 5.6] | 0.64 |

| Macrolides | 833 | 3.8 [3.5; 4.0] | 545 | 3.9 [3.6; 4.2] | 0.63 |

| Lincosamides | 699 | 3.2 [2.9; 3.4] | 487 | 3.5 [3.2; 3.8] | 0.15 |

| Extended-spectrum penicillins | 682 | 3.1 [2.9; 3.3] | 765 | 5.4 [5.1; 5.8] | <0.01 |

| Glycopeptide antibiotics | 653 | 3.0 [2.7; 3.2] | 410 | 2.9 (2.6; 3.2] | 0.81 |

The two-sided chi-square test was used to calculate the p values.

CI, confidence interval

eTable 2. The most commonly used classes of antibiotics for treatment and prophylaxis (comparison 2016 versus 2011).

| 2016 | 2011 | |||||||||

|

Class of antibiotics |

Total number of antibiotic treatments (%)* |

Prophylaxis non- surgical indication (%) |

Prophylaxis perioperative (%) |

Treatment of CI (%) |

Treatment of NI (%) |

Total number of antibiotic treatments (%)* |

Prophylaxis non-surgical indication (%) |

Prophylaxis perioperative (%) |

Treatment of CI (%) |

Treatment of NI (%) |

| PeniciBLI | 5119 (23.2) | 167 (3.3) | 390 (7,6) | 3 304 (64.5) | 989 (19.3) | 1773 (12.6) | 128 (7.2) | 274 (15.5) | 866 (48.8) | 438 (24.7) |

| Cephalo2 | 2856 (12.9) | 91 (3.2) | 1366 (47,8) | 1048 (36.7) | 233 (8.2) | 2054 (14.6) | 115 (5.6) | 953 (46.4) | 686 (33.4) | 234 (11.4) |

| Fluoro‧chinolones | 2494 (11.3) | 188 (7.5) | 224 (9,0) | 1355 (54.3) | 591 (23.7) | 1971 (14.0) | 233 (11.8) | 231 (11.7) | 899 (45.6) | 513 (26.0) |

| Cephalo3 | 1971 (8.9) | 128 (6.5) | 168 (8,5) | 1290 (65.4) | 252 (12.8) | 1498 (10.6) | 99 (6.6) | 177 (11.8) | 838 (55.9) | 313 (20.9) |

| Carbapenems | 1369 (6.2) | 57 (4.2) | 41 (3,0) | 686 (50.1) | 509 (37.2) | 825 (5.9) | 46 (5.6) | 32 (3.9) | 377 (45.7) | 350 (42.4) |

|

Imidazole derivates |

1138 (5.2) | 40 (3.5) | 268 (23,6) | 622 (54.7) | 150 (13.2) | 741 (5.3) | 46 (6.2) | 210 (28.3) | 335 (45.2) | 118 (15.9) |

| Macrolides | 833 (3.8) | 39 (4.7) | 10 (1.2) | 622 (74.7) | 71 (8.5) | 545 (3.9) | 29 (5.3) | 15 (2.8) | 356 (65.3) | 89 (16.3) |

| Lincosamides | 699 (3.2) | 29 (4.1) | 103 (14.7) | 414 (59.2) | 116 (16.6) | 477 (3.4) | 23 (4.8) | 96 (20.1) | 239 (50.1) | 104 (21.8) |

| PeniciES | 682 (3.1) | 83 (12.2) | 60 (8.8) | 427 (62.6) | 67 (9.8) | 765 (5.4) | 89 (11.6) | 115 (15.0) | 368 (48.1) | 142 (18.6) |

| GlykopAB | 653 (3.0) | 23 (3.5) | 31 (4.7) | 277 (42.4) | 286 (43.8) | 410 (2.9) | 24 (5.9) | 18 (4.4) | 132 (32.2) | 228 (55.6) |

| Other | 4 272 (19.3) | 667 (15.6) | 617 (14.4) | 1658 (38.8) | 1147 (26.8) | 3017 (21.4) | 523 (17.3) | 535 (17.7) | 1047 (34.7) | 809 (26.8) |

All absolute values refer to the number of antibiotic treatments. CI, community-acquired infection; NI, nosocomial infections; PeniBLI, combinations of penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors; Cephalo2, second-generation cephalosporins; Cephalo3, third-generation cephalosporins; PeniciES, penicillins with extended spectrum; GlykopAB, glycopeptide antibiotics

* Referring to the total number of the mentioned classes of antibiotics of the calendar year; all other percentage values refer to the respective class of antibiotics.

Discussion and conclusions

In addition to the hospitals included in the representative sample, once again a large number of hospitals agreed to voluntarily participate in the national prevalence study. Even though the survey created a comparatively high workload for the infection prevention and control professionals of the hospitals, the staff members considered it important to participate. Participating in the survey provides hospitals with an opportunity to enhance their internal quality management with additional indicators of how their own hospital is positioned in comparison to other hospitals, potentially stimulating further preventive actions or antibiotic stewardship (ABS) activities.

According to results in the overall group and the representative sample, the number of NIs has decreased over the last five years. Even if the scope of the survey was limited to NIs acquired during the current hospital stay, NI prevalence was with 3.5% lower in the representative sample than in the 1994 national prevalence survey (9).

Increased public awareness of this topic and the amended legal framework in the German federal states have certainly helped to bring about change so that hospitals now give higher priority to the prevention of NIs (10). Many hospitals responded by employing additional infection prevention and control doctors, almost doubling their numbers compared to 2011. In the data of all participating hospitals, it is noteworthy that the consumption of hand rub increased. This change may also be related to other national hygiene activities, such as the Clean Hands initiative with more than 1800 participating healthcare facilities (11, 12).

However, when interpreting the decrease in NI rates various parameters have to be taken into account:

The lower median number of hospital beds in the overall group of participating hospitals in 2016 compared to 2011 (305 versus 359) indicates that the proportion of smaller hospital was greater in the 2016 survey. It is a known fact that NI rates are generally lower in smaller hospitals, since the risk structure of their patients is on a lower level and their diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are less invasive (13).

Selection of the group of representative hospitals took only hospital bed numbers into account and not possible specializations or specialties. This may limit the representativeness of the sample.

The median length of hospital stay decreased in the group of all participating hospitals by 0.3 days. This also reduced the chance to diagnose NI during the hospital stay.

This reduction in NI prevalence was not confirmed in the core group of hospitals that had participated in both surveys. Theoretically, the core group is ideally suited for a comparison of the years 2011 and 2016. However, it seems that these hospitals had also undergone significant changes in the interval between the two surveys; for example, the median number of hospital beds increased from 368 to 392. Furthermore, these hospitals differ from others as they have more hospital beds (392 versus 305 in all participating hospitals and 205 in the representative sample) and were motivated to participate again in a point prevalence survey.

To limit the survey-related workload of participating hospitals, it had been decided at the planning stage of the study to not document risk factors for patients without NI. Therefore, it is not possible to adjust the results to compensate potential changes in the risk structure of the patients

The ECDC survey protocol defined in 2016 as in 2011 that a patient was considered to have a nosocomial infection if the microbiological result of the NI was available at the day of the prevalence survey. Therefore, the overall prevalence of NI is presumably higher than the one calculated in this study. No information was gathered about how many positive results that were not yet available at the day of the survey led to NI. Even though this is certainly a limitation of this study, it does not affect the pan-European comparability of national prevalence rates.

The survey was conducted from May to June 2016. In 2011, data collection was carried out in September and October. No effects on nosocomial infection rates are known regarding the transitory seasons (14).

When evaluating the increase in CDI in 2016, it has to be taken into account that in recent years many hospitals introduced diagnostic tests with improved sensitivity (15, 16). Thus, it is uncertain whether the actual prevalence has really increased.

In comparison to the decrease in NIs, the prevalence of AU has not changed in the overall group during the last five years. It is notable that the use of penicillins with �-lactamase inhibitors has increased significantly and that all of the five most commonly used classes of antibiotics include only broad-spectrum antibiotics, except for second-generation cephalosporins which are primarily used for perioperative prophylaxis. Most likely, this development is driven by the increase in multi-resistant gram-negative pathogens (17). Overall, the distribution of AU is in line with a recently published study analyzing usage data in German hospitals (18). The finding that in 31.3% of patients the indication for antibiotic use is not documented is of concern. Regular documentation could lead to more conscious decisions against the use of antibiotics in questionable cases.

Results from other EU countries are expected to become available in 2018 or 2019. Then, the ECDC will undertake national comparisons based on the representative samples for which in Germany a reduction in NI results.

However, when all studied groups are included in the analysis this reduction is not clearly demonstrated. Overall, the results indicate that the increased efforts of the hospitals, for example with regards to the number of infection prevention and control professionals and hand hygiene, as well as structural changes, have resulted in a successful reduction of NI in recent years. However, antibiotic stewardship activities did not help to measurably improve the situation in various hospitals in Germany.

Key Messages.

Between 2011 and 2016, the number of nosocomial (healthcare-associated) infections decreased, according to the results of the representative sample and the overall group. By contrast, the prevalence of antibiotic use decreased only in the representative sample of hospitals.

In all groups, significantly more infection prevention and control nurses and infection prevention and control doctors were employed in 2016 compared to 2011.

The consumption of alcohol hand rubs per patient only increased in the overall group.

Lower respiratory infections accounted for the largest share (24%) of nosocomial infections in the overall group in 2016, followed surgical site infections (22.4%).

The ECDC-selected group of representative hospitals was compiled solely on the basis of number of hospital beds. Specialization and specialty were not taken into account.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Prof. Gastmeier received study support (third-party funding) from B. Braun and Bode.

The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals 2011-12. ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/point-prevalence-survey-healthcare-associated-infections-and-antimicrobial-use-0 (last accessed on 4 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassini A, Plachouras D, Eckmanns T, et al. Burden of six healthcare-associated infections on European population health: estimating incidence-based disability-adjusted life years through a population prevalence-based modelling study. PLoS Med. 2016;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002150. e1002150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behnke M, Hansen S, Leistner R, et al. Nosocomial infection and antibiotic use—a second national prevalence study in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:627–633. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen S, Sohr D, Piening B, et al. Antibiotic usage in German hospitals: results of the second national prevalence study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2934–2939. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nationales Referenzzentrum für die Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. PPS Protokoll DE 2017. www.nrz-hygiene.de/fileadmin/nrz/download/pps2016/EUPPS2016DE_Protokoll_Version_4.6.pdf (last accessed on 4 August 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nationales Referenzzentrum für die Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. PPS Codiertabellen und Definitionen nosokomialer Infektionen 2017. www.nrz-hygiene.de/fileadmin/nrz/download/pps2016/EUPPS2016DE_Codiertabellen_Version_4.9.pdf (last accessed on 15 September 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index_and_guidelines/guidelines (last accessed on 3 February 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistisches Bundesamt. Deutsches Krankenhausverzeichnis 2015. www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Krankenhaeuser/Krankenhausverzeichnis.html (last accessed on 3 February 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rüden H, Gastmeier P, Daschner F, Schumacher M. [Nosocomial infection in Germany: epidemiology in the old and new Federal Lands] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1996;121:1281–1287. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen S, Schwab F, Gropmann A, Behnke M, Gastmeier P, PROHIBIT Consortium. Hygiene und Sicherheitskultur in deutschen Krankenhäusern. Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2016;59:908–915. doi: 10.1007/s00103-016-2373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetzker W, Bunte-Schönberger K, Walter J, Pilarski G, Gastmeier P, Reichardt C. Compliance with hand hygiene: reference data from the national hand hygiene campaign in Germany. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:328–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetzker W, Walter J, Bunte-Schönberger K, et al. Hand rub consumption has almost doubled in 132 German hospitals over 9 years. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38:870–872. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gastmeier P, Kampf G, Wischnewski N, et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in representatively selected German hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schröder C, Schwab F, Behnke M, et al. Epidemiology of healthcare associated infections in Germany: nearly 20 years of surveillance. Int J Med Mikro. 2015;305:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longtin Y, Trottier S, Brochu G, et al. Impact of the type of diagnostic assay on clostridium difficile infection and complication rates in a mandatory reporting program. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:67–73. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polage C, Gyorke C, Kennedy M, et al. Overdiagnosis of clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1792–1801. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geffers C, Maechler F, Behnke M, Gastmeier P. Multiresistente Erreger: Epidemiologie, Surveillance und Bedeutung. Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2016;51:104–110. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-103348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kern W, Fellhauer M, Hug M, et al. [Recent antibiotic use in German acute care hospitals—from benchmarking to improved prescribing and quality care] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:e237–e246. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-105938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]