Abstract

Background

Uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired urinary tract infection is among the more common infections in outpatient practice. The resistance level of pathogens has risen markedly. This S3 guideline contains recommendations based on current evidence for the rational use of antimicrobial agents and for the prevention of inappropriate use of certain classes of antibiotics and thus of the resulting drug resistance. The prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection is considered in this guideline for the first time.

Methods

The guideline was updated under the aegis of the German Urological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie). A systematic literature search (period: 2008–2015) concerning the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of uncomplicated urinary tract infections was carried out in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Embase databases. Randomized, controlled trials and systemic reviews were included. Relevant guidelines were identified in a guideline synopsis.

Results

Symptom-oriented diagnostic evaluation is highly valued. For the treatment of cystitis, fosfomycin-trometamol, nitrofurantoin, nitroxolin, pivmecillinam and trimethoprim are all equally recommended. Fluorquinolones and cephalosporins are not recommended. Uncomplicated pyelonephritis with a mild to moderate clinical course ought to be treated with oral cefpodoxime, ceftibuten, ciprofloxacin, or levofloxacin. For acute, uncomplicated cystitis, with mild to moderate symptoms, symptomatic treatment alone may be considered instead of antibiotics after discussion of the options with the patient. Mainly non-antibiotic measures are recommended for prophylaxis against recurrent urinary tract infection.

Conclusion

Physicians who treat uncomplicated urinary tract infections should familiarize themselves with the newly revised guideline’s recommendations on the selection and dosage of antibiotic treatment so that they can responsibly evaluate and plan antibiotic treatment for their affected patients.

Uncomplicated bacterial urinary tract infection is one of the most commonly occurring community-acquired infections. In 2013, 7.32% of the female members of the German health insurance fund Barmer GEK were diagnosed with uncomplicated urinary tract infection (uUTI; ICD-10 code N39.0), 1.73% with acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC; N30.0), and 0.16% with acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (AUP: N10) (1). The estimated incidence of UTI in women over 18 years of age in the USA is 12.6% (2). On the basis of the Barmer GEK data, German prescription practice for diagnosed cystitis runs contrary to the recommendations of the guideline issued in 2010. For example, the drug class most commonly prescribed for the treatment of UTI in 2012 was a fluoroquinolone, given in 48% of cases (1). Antibiotic resistance is a growing global problem that is leading to considerably increased costs and daunting challenges in health care (1, 3– 5). According to the data of the ARMIN resistance-monitoring project in the German federal state of Lower Saxony, for instance, resistance of Escherichia coli to ciprofloxacin has increased from 10.3% to 14.7% in the past 10 years (6). Growing resistance to cotrimoxazole and ampicillin has also been noted (7, 8). It is known that different antibiotics exert a varying amount of selection pressure not only on the pathogens responsible for the infection, but also on the uninvolved local flora. This is termed collateral damage, and the substances used in the treatment of uncomplicated UTI with the greatest effect in this respect are the cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.

The goal of updating the guideline is to provide clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired UTI in adults. The recommendations and statements are intended to help members of all professions concerned with the diagnosis, treatment, and prophylaxis of acute uUTI: primary-care physicians, gynecologists, infectious disease specialists, internists working in primary care, clinical pathologists, microbiologists, urologists, and pharmacists.

Method

The revised S3 guideline was compiled according to the regulations of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) (9) under the aegis of the German Urology Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU). It was decided not to solicit or accept funding from the pharmaceutical industry. All authors’ conflicts of interests were publicized. The content of the central statements and recommendations was voted on separately by experts with and without conflicts of interest. A complete list of the authors of the updated S3 guideline and the professional societies they represent is provided in the eBox.

eBOX. Authors/officers of the updated AWMF S3 guideline with the professional societies they represent.

Prof. Dr. med. Reinhard Fünfstück, German Society of Nephrology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nephrologie, DGfN), Paul Ehrlich Society of Chemotherapy (Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, PEG)

Dr. med. Sina Helbig, German Society of Infectious Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Infektiologie, DGI)

Prof. Dr. med. Walter Hofmann, German Society of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Klinische Chemie und Laboratoriumsmedizin, DGKL)

Prof. Dr. med. Udo Hoyme, German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe, DGGG)

Prof. Dr. med. Eva Hummers, German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Familienmedizin, DEGAM)

Dr. med. Mirjam Kunze, German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe, DGGG)

Dr. med. Jennifer Kranz, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU), UroEvidence@Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, Berlin

Dr. med. Eberhard Kniehl, German Society of Hygiene and Microbiology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hygiene und Mikrobiologie, DGHM), Paul Ehrlich Society of Chemotherapy (Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, PEG)

Dr. med. Cordula Lebert, National Federation of German Hospital Pharmacists (Bundesverband Deutscher Krankenhausapotheker, ADKA)

Prof. Dr. med. Kurt G. Naber, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU), Paul Ehrlich Society of Chemotherapy (Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, PEG)

Dr. med. Falitsa Mandraka, German Society of Infectious Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Infektiologie, DGI)

Bärbel Mündner-Hensen, ICA-Deutschland e. V., Förderverein Interstitielle Zystitis (a German organization dedicated to providing information about interstitial cystitis)

Dr. med. Laila Schneidewind, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU), UroEvidence@Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, Berlin

PD Dr. med. Guido Schmiemann, German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Familienmedizin, DEGAM)

Dr. med. Stefanie Schmidt, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU), UroEvidence@Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, Berlin

Prof. Dr. med. Urban Sester, German Society of Nephrology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nephrologie, DGfN)

PD Dr. med. Winfried Vahlensieck, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU)

Prof. Dr. med. Florian Wagenlehner, German Society of Urology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, DGU), Paul Ehrlich Society of Chemotherapy (Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, PEG)

For the first time, the guideline was supported by UroEvidence@Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie, the knowledge transfer center of the DGU. UroEvidence was responsible for sifting of the identified publications by two experts working independently (JK, SS), literature management (JK, SS), and assessment of the level of evidence and risk of bias in the treatment studies (JK, SS, LS). Evidence assessment was based on the results of a systematic survey of the literature on the topics diagnosis and treatment of uUTI and prevention of recurring UTI (rUTI). Details of the search strategy can be found (in German) in the long version of the guideline (10). The databases Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, and Embase were searched for publications in the period 1 January 2008 (continuing from the systematic survey carried out for the first edition of the guideline published in 2010) to 31 December 2015. Furthermore, the data of all currently available relevant studies were incorporated in the interests of a “living guideline.” The publications identified by the literature search were sorted according to topic and divided accordingly among the working groups. To be included, studies not only had to have a patient population as defined below, but also had to fulfill the requirements for study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT) or systematic review with or without meta-analysis. A flow chart of the literature survey according to the PRISMA statement (11) is shown in eFigure 1. The risk of bias was assessed for all studies included: for RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, for systematic reviews and meta-analyses using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) system (12, 13). Assessment of the level of evidence followed the 2009 criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (14). The evidence tables (effect sizes) of the recommended antibiotics are shown in T5.

eFigure 1.

Flow chart of literature survey according to PRISMA statement (11)

eTabelle 1. Effektstärken der verschiedenen empfohlenen Antibiotika.

| Reference |

Level of evidence & Risk of Bias* |

Outcome |

Intervention & number of patients |

Dosage | Duration |

Comparison & number of patients |

Dosage | Duration | |

| Randomized controlled trials | |||||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | |||||||||

| Bleidorn 2010 (e28) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment - Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias - |

Uncomplicated lower UTI Primary outcomes: Symptom resolution on day 4: Ibuprofen: 58.3% Ciprofloxacin: 51.5%, p=0.744 Secondary outcomes: Symptom burden day 4: Ibuprofen: mean 0.97, SD 1.42 Ciprofloxacin: mean 1.3, SD 1.9 Symptom burden day 7: Ibuprofen: mean 0.67, SD 1.26 Ciprofloxacin: mean 0.61, SD 0.86 Symptom resolution day 7: Ibuprofen: 75% Ciprofloxacin: 60.6%, p=0.306 Frequency of relapse (secondary antibiotic treatment day 0 to 9; per protocol analysis): Ibuprofen: 33.3% Ciprofloxacin: 18.2%, p=0.247 |

Ibuprofen N=40 |

3 × 400 mg | 3 days | Ciprofloxacin N=39 |

2 x 250mg (+1 placebo) | 3 days | |

| Ceran 2010 (e29) |

IIb Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data + Selective outcome reporting ? Other bias ? |

Uncomplicated lower UTI Clinical effects (clinical response= disappearance of signs and symptoms): FMT 83.1% Ciprofloxacin 81%, p>0.05 Bacteriological effects (antibiotic sensitivity): FMT 83.1% Ciprofloxacin 78.4%, p>0.05 Improvement of urinary findings: FMT 80.5% |

Fosfomycin trometamol (FMT) N=77 |

1 x 3g | 1 day | Ciprofloxacin N=65 |

2 x 500mg | 5 days | |

| Ciprofloxacin 80% | |||||||||

| Hooton 2012 (e30) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment ? Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Women with acute uncomplicated cystitis Primary outcomes: Overall clinical cure: 11% difference, CI95% [3; 8] Secondary outcomes: Early clinical cure (at first followup visit): 5% difference, CI95% [1; 12] Early microbiological cure (at first followup visit): 15% difference, CI95% [8; 23] |

Ciprofloxacin N=150 |

2 x 250mg | 3 days | Cefpodoxime N=150 |

2 x 100mg | 3 days | |

| Palou 2013 (e31) |

Ib Random sequence generation ? Allocation concealment ? Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment ? Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting + Other bias ? |

Women post-menopause with lower UTI Eradication: FMT, N, %: 23, 62.16 Cipro, N, %: 23, 58.97 Persistence: FMT, N, %: 10, 27.03 Cipro, N, %: 9, 23.08 New infection: FMT, N, %: 4, 10.81 Cipro, N, %: 7, 17.95 Clinical cure: FMT, N, %: 32, 86.49 Cipro, N, %: 32, 82.05 Clinical improvement: FMT, N, %: 1, 2.7 Cipro, N, %: 2, 5.13 Clinical failure: FMT, N, %: 4, 10.81 Cipro, N, %: 4, 10.26 relapse: FMT, N, %: 0, 0 Cipro, N, %: 1, 2.56 |

Fosfomycin trometamol N=59 |

2 x 3g | 2 doses separated by 72hrs |

Ciprofloxacin N=59 |

2 x 250mg | 3 days | |

| Peterson | Ib | Complicated UTI and acute pyelonephritis | Levofloxacin | 1 x 750mg IV or orally | 5 days | Ciprofloxacin | 2 x 400mg IV and/or | 10 | |

| 2008 (e32) |

Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias? |

Eradication rate end of therapy: Levofloxacin (N, %): 253, 79.8 Ciprofloxacin (N, %): 234, 77.5 Clinical success rate end of therapy: Levofloxacin (N, %): 262, 82.6 Ciprofloxacin (N, %): 210, 87.1 |

N=543 |

N=559 |

2 x 500mg orally | days | |||

| Fosfomycin | |||||||||

| Ceran 2010 (e29) |

IIb Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data + Selective outcome reporting ? Other bias ? |

Uncomplicated lower UTI Clinical effects (clinical response= disappearance of signs and symptoms): FMT 83.1% Ciprofloxacin 81%, p>0.05 Bacteriological effects (antibiotic sensitivity): FMT 83.1% Ciprofloxacin 78.4%, p>0,05 Improvement of urinary findings: FMT 80.5% Ciprofloxacin 80% |

Fosfomycin trometamol (FMT) N=77 |

1 x 3g | 1 day | Ciprofloxacin N=65 |

2 x 500mg | 5 days | |

| Palou 2013 (e31) |

Ib Random sequence generation ? Allocation concealment ? Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment ? Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting + Other bias ? |

Women post-menopause with lower UTI Eradication: FMT, N, %: 23, 62.16 Ciprofloxacin, N, %: 23, 58.97 Persistence: FMT, N, %: 10, 27.03 Ciprofloxacin, N, %: 9, 23.08 New infection: FMT, N, %: 4, 10.81 Ciprofloxacin, N, %: 7, 17.95 Clinical cure: FMT, N %: 32, 86.49 Ciprofloxacin, N, %: 32, 82.05 |

Fosfomycin trometamol N=59 |

2 x 3g | 2 doses separated by 72 hours |

Ciprofloxacin N=59 |

2 x 250mg | 3 days | |

| Clinical improvement: FMT, N, %: 1, 2.7 Ciprofloaxin, N, %: 2, 5.13 Clinical failure: FMT, N, %: 4, 10.81 Ciprofloaxin, N, %: 4, 10.26 relapse: FMT, N, %: 0, 0 Ciprofloxacin, N, %: 1, 2.56 |

|||||||||

| Estebanez 2009 (e33) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Pregnant women Eradication rate (primary outcome): Similar in both groups, over 80% RR=1.195, CI95% [0.451; 3.165], p=0.720 Reinfection: Lower with fosfomycin RR=0.13, CI95% [0.02; 0.81], p=0.045 Adverse effects: Lower with fosfomycin RR=0.10, CI95% [0.01; 0.72], p=0.008 Persistence: RR=2.64, CI95% [0.59; 11.79], p=0.39 Development of symptomatic UTI: p=0.319 Recurrences: RR=1.06, CI95% [0.11; 10.12], p=0.96 |

Fosfomycin N=53 |

1 x 3g | 1 day | Amoxicillin–clavulanate N=56 |

3 x 500mg/125mg | 7 days | |

| Gágyor 2015 (26) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment - Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - |

UTI in women Primary outcomes: Total number of courses of antibiotics for UTIs days 0-28 during followup (N, %): Ibuprofen: 75, 31 Fosfomycin: 30, 12 mean difference: 18.8, CI95% [11.6; 25.9] Symptom burden day 0-7 (mean, SD): Ibuprofen: 17.3, 11.0 Fosfomycin: 12.1, 8.2 |

Fosfomycin N=246 |

1x 3 g | 1 day | Ibuprofen N=248 |

3x400mg | 3 days | |

| Other bias - | mean difference: 5.3, CI95% [3.5; 7.0] secondary outcomes: adverse events (patient reported, N, %): Ibuprofen: 42, 17 Fosfomycin: 57, 24 mean difference: -6.0, CI95% [-13.2; 1.1] recurrence days 15-28, rated by GP (N, %): Ibuprofen: 14, 6 Fosfomycin: 27, 11 mean difference: -5.3, CI95% [-10.2; 0.4] Symptom free at day 7: Ibuprofen: 163/232, 70 Fosfomycin: 186/227, 82 mean difference: -11.7, CI95% [-19.4; -4.0] |

||||||||

| Pivmecillinam | |||||||||

| Monsen 2014 (e34) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Symptomatic UTI Symptom free at last follow-up (day 35-49 post inclusion): PIV (total): 68% Placebo: 54%, p<0.01 |

Pivmecillinam N=855 |

3 x 200mg | 7 days | Pivmecillinam or Pivmecillinam or Placebo N=288 |

2 x 200mg 2 x 400mg |

7 days 3 days |

|

| Bjerrum 2009 (e35) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias - |

Uncomplicated cystitis Primary Outcomes: Drug efficacy (clinical cure at follow-up visit 7-10 days): Pivmecillinam: 68.8% Sulfamethizole: 77.9% (difference -9.2%, CI95% [-24.7; 6.3]. Secondary Outcomes: Bacteriological Cure (<10 hoch 3 cfu/ml): Pivmecillinam: 68.8% Sulfamethizole: 77.9% (difference 9.2%, CI95% [24.7; 6.3]. |

Pivmecillinam N=89 |

3 x 400mg | 3 days | Sulfamethizole N=86 |

2 x 1g | 3 days | |

| Recurrence within 6 months (GP survey data): Pivmecilliam: 26.8% Sulfamethizole: 18.4% (difference 8.4%, CI95% [-4.5; 21.4%] |

|||||||||

| Kazemier 2015 (28) Prospective cohort with embedded RCT |

Ib-IIb Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment - Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias - |

Asymptomatic pregnant women Primary outcomes: Composite (Pyelonephritis +delivery): Risk difference -0.4, CI95% [-3.6; 9.4] Pyelonephritis: Risk difference -2.4, CI95% [-19.2; 14.5] Delivery <34 weeks: Risk difference -1.5, CI95% [-15.3; 18.5] |

Nitrofurantoin N=40 |

2x 100mg | 5 days | Placebo N=45 Comparison is made with N=208, which is placebo or untreated (from cohort study). |

2x | 5 days | |

| Lumbiganon 2009 (e36) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment ? Incomplete outcome data ? Selective outcome reporting ? Other bias ? |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy Primary outcomes: Bacterial cure on day 14: Cure rate difference: -10.5, CI95% [-16.1; -4.9] Cure rate ratio: 0.88, CI95% [0.82; 0.94] Secondary outcomes: Different Adverse effects. Different pregnancy outcomes. |

Nitrofurantoin N=386 |

2 x 100mg | 1 day | Nitrofurantoin N=392 |

2 x 100mg | 7 days | |

| Other | |||||||||

| Little 2010 (e37) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - |

Women with uncomplicated UTI Effectiveness: Frequency symptom severity (mean difference, SD): Immediate: 2.15, 1.18 Midstream urine: 2.08, -0.07 Dipstick: 1.74, -0.40 Symptom score: 1.77, -0.38 Delayed antibiotics: 2.11, -0.04, p=0.177 Duration of moderately bad symptoms in days (incidence ratio): |

Immediate antibiotics |

Midstream urine or Dipstick or Symptom score or Delayed antibiotics |

|||||

| Other bias ? | Immediate: 1 Midstream urine: 1.21 Dipstick: 0.91 Symptom score: 1.11 Delayed antibiotics: 1.12, p=0.369 Mean unwell symptom severity (mean difference, SD): Immediate: 1.60, 1.30 Midstream urine: 1.66, 0.05 Dipstick: 1.32, -0.28 Symptom score: 1.26, -0.35 Delayed antibiotics: 1.43, -0.18, p=0.392 Odds ratio for antibiotic use: Immediate: 97% Midstream urine: 0.15, CI95% [0.03; 0.73] Dipstick: 0.13, CI95% [0.03; 0.63] Symptom score: 0.29, CI95% [0.06; 1.55] Delayed antibiotics: 0.12, CI95% [0.03; 0.59], p=0.011 Time to reconsultation (hazard ratio): Immediate: 1 Midstream urine: 0.81, CI95% [0.47; 1.39] Dipstick: 0.98, CI95% [0.58; 1.65] Symptom score: 0.73, CI95% [0.43; 1.22] Delayed antibiotics: 0.60, CI95% [0.35; 1.05] p=0.345 |

||||||||

| Monmaturap oj 2012 (e38) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Acute pyelonephritis All patients were given 2g ceftriaxone (IV) over 30min 1x daily as an initial antibiotic agent. After day 3, patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria and the criteria for switch therapy were enrolled and randomized to either the control or study group regimens. Clinical cure (N, %): Group B: 41, 100 Group A: 39, 95.1 Symptom improvement (N, %): Group B: 0 Group A: 1, 2.4 Treatment failure (N, %): Group B: 0 |

Group B: Placebo (IV) + Cefditoren pivoxil N=41 |

4x 100mg + placebo (IV) | 10 days | Group A: ceftraxione (IV) + oral placebo 4 tablets N=41 |

4 x 100mg + 2g ceftriaxone (IV) |

10 days | |

| Group A: 1, 2.4 Bacteriological eradication (N, %): Group B: 24, 60 Group A: 26, 63.4 |

|||||||||

| Shaheen 2015 (e39) |

IIb Random sequence generation + Allocation concealment + Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment ? Incomplete outcome data ? Selective outcome reporting ? Other bias ? |

Urinary tract infections Improved: CranAdvantage (N, %): 23, 35.38 Urixin (N, %): 15, 23.07 Not improved: CranAdvantage (N, %): 42, 64.61 Urixin (N, %): 50, 76.92 |

CranAdvantage N=65 |

2 x 500mg | 2-3 weeks | Urixin N= 65 |

2 x 400mg | 2-3 weeks | |

| Stein 2011 (e40) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data ? Selective outcome reporting ? Other bias ? |

Women with suspected UTI | Computer – expedited management group N=61 |

Usual care N=42 |

|||||

| Turner 2010 (e41) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data + Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Women with UTI Cost-effectiveness analysis |

Immediate antibiotics N=56 |

Midstream urine N= 46 Dipstick N=42 Symptom scores N=60 Delayed antibiotics N=53 |

|||||

| Drozdov 2015 (e42) RCT |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment ? Blinding of participants and personal + Blinding of outcome data assessment + Incomplete outcome data ? Selective outcome reporting - Other bias ? |

Uncomplicated UTI Primary outcome: Overall antibiotic exposure within 90 days: Intervention: Median 7.0, IQR 5.0 to 14.0, control: Median 10.0, IQR 7.0 to 16.0, p=0.011 Secondary outcome: no differences found. (Duration of therapy; Persistant infection 7 days and 30 days after; Recurrence; Hospitalization within 90 days) |

Dif. Antibiotics, administrationbased on algorithm N=63 |

Dif. Antibiotics, administration based on standard guideline N=66 |

|||||

| Wagenlehner 2015 (e44) |

Ib Random sequence generation - Allocation concealment - Blinding of participants and personal - Blinding of outcome data assessment - Incomplete outcome data - Selective outcome reporting - Other bias - |

Complicated UTI and pyelonephritis Microbiological eradication (N, %, CI95%): Cefto.: 320, 80.4 [2.4-; 4.1] Levo.: 290, 72.1 % difference: 8.3, CI95% [2.4; 14.1] Clinical cure (N, %, CI95%): Ceftolozane/tazobactam.: 366, 92.0 Levofloxacin.: 356, 88.6 % difference: 3.4, CI95% [-0.7, 7.6] |

Ceftolozane- tazobactam N=543 |

3 x 1,5g iv | 7 days | Levofloxacin N=540 |

1 x 750 mg iv | 7 days | |

| Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | |||||||||

| Costelloe 2010 (e44) MA |

IIa High quality |

Individuals prescribed antibiotics in primary care Resistance (UTI only) at 0-12 months: OR= 1.33, CI95% [1.15; 1.53] |

Antibiotic use | No antibiotic | |||||

| Eliakim-Raz 2013 (e45) MA |

Ia Acceptable quality |

Acute Pyelonephritis and septic UTI RCTs=8 Primary outcomes: Clinical failure at end of treatment (at 10-14 days): 5 RCT, RR=0.63, CI95% [0.33; 1.18] Secondary outcomes: |

Different antibiotics | <= 7 days | Different antibiotics | > 7 days | |||

| Clinical failure at end of followup: 7 RCT, RR=0.79, CI95% [0.56; 1.12] Microbiological failure at end of treatment: 8 RCT, RR=0.60, CI95% [0.09; 3.86] Microbiological failure at end of followup: 8 RCT, RR=1.16, CI95% [0.83; 1.62] any adverse event: 7 RCTs, RR=0.93, CI95% [0.73; 1.18] |

|||||||||

| Falagas 2009 (e46) MA |

Ia High quality |

Patients with cystitis. 5 RCTs on non-pregnant, non-immunocompromised adult women Clinical success (cure and non-cure but symptom relief): Antibiotics superior 4 RCTs, 1062 patients, OR=4.81, CI95% [2.51; 9.21] Clinical success (cure): Antibiotics superior 4 RCTs, 967 patients, OR=4.67, CI95% [2.34; 9.35] Microbiological eradication (at end of treatment): Antibiotics superior 3 RCTs, 1062 patients, OR=10.67, CI95% [2.96; 38.43] Microbiological eradication (after end of treatment): Antibiotics superior 3 RCTs, 738 patients, OR=5.38, CI95% [1.63; 17.77] Microbiological reinfection or relapse (after end of treatment): Antibiotics superior 5 RCTs, 843 patients, OR=0.27, CI95% [0.13; 0.55] No difference was found between the compared treatment arms regarding study withdrawals from adverse events, the development of pyelonephritis and emergence of resistance. |

Different antibiotics | placebo | |||||

| Falagas 2010 (e47) MA |

Ia High quality |

Patients with cystitis. 27 trials (8 double-blind) included. 16/27 on non-pregnant female patients, 3 adult mixed populations of older age, 5 on pregnant patients, 3 on paediatric patients. Clinical success (non-pregnant and mixed populations, complete cure and improvement of symptoms): no difference regarding all comparators combined [10 RCTs, 1657 patients, RR= 1.00, CI95% [0.98; 1.03] |

Fosfomycin | Other antibiotics | |||||

| Insufficient relevant data for paediatric and pregnant patients. No difference between fosfomycin and comparators was also found in all comparisons regarding the remaining effectiveness outcomes (namely microbiological success/relapse/re-infection). Fosfomycin had a comparable safety profile with the evaluated comparators in non-pregnant women, mixed and paediatric populations, whereas it was associated with significantly fewer adverse events in pregnant women (4 RCTs, 507 patients, RR=0.35, CI95% [0.12; 0.97] |

|||||||||

| Flower 2015 (e48) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Women with recurrent UTIs Effectiveness (CHM vs antibiotic): 3 RCT, RR 1.21, CI95% [1.11; 1.33] Recurrence (CHM vs antibiotic): 3 RCT, RR 0.28, CI95% [0.09, 0.82] |

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) only |

Chinese herbal medicine combined with active placebo or conventional biomedical treatment | |||||

| Guinto 2010 (e49) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy Fosfomycin Trometamol versus Cefuroxime: Persistent infection: RR, CI95%: 1.36, [0.24; 0.75] Adverse event: RR, CI95%: 2.73, [0.11; 65.24] Pivmecillinam versus Ampicillin (RR, CI95%:): Persistent infection after 6 weeks: 0.67, [0.29-; 1.54] Recurrences: 0.69, [0.12-; 0.85] 1-day Nitrofurantoin versus 7-day Nitrofurantoin (RR, CI95%): Symptomatic infection at 2 weeks: 0.71, [0.23; 2.22] Persistence: 1.76, [1.29; 2.46] Preterm delivery: 1.24, [0.79; 1.94] Pivampicillin/Pivmecillinam (Miraxid) versus Cephalexin (RR, CI95%): Persistence: 5.75, [0.75; 44.15] Recurrence: 0.77, [0.23; 2.5] Cycloserine versus Sulphadimidine (RR, CI95%): symptomatic infection: 0.62, [0.33; 1.16] persistence: 0.70, [0.41; 1.21] recurrence: 0.89, [0.47; 1.68] |

Different antibiotics | Different antibiotics | |||||

| Gutiérrez- Castrellón 2015 (e50) MA |

Ia Acceptable quality |

Acute and complicated UTIs (results for acute UTI) Primary outcomes: Bacteriological eradication end of treatment: RR=1.01, CI95% [0.99; 1.04] Clinical cure end of treatment: |

Ciprofloxacin | Other antibiotics | |||||

| RR=1.00, CI95% [0.98; 1.02] Resistance: RR=0.97, CI95% [0.67; 1.39] Adverse events: RR=0.88, CI95% [0.81; 0.96] |

|||||||||

| Jepson 2014 (e51) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Lower UTIs 24 studies Canberry products vs placebo, water or no treatment (RR 0.86, 95%CI [0.71; 1.04] subgroups: women with recurrent UTIs (RR 0.74, CI95% [0.42; 1.31]; older people (RR 0.75, CI95% [0.39; 1.44]; pregnant women (RR 1.04, CI95% [0.97; 1.17]; children with recurrent UTI (RR 0.48, CI95% [0.19; 1.22]; cancer patients (RR 1.15 CI95% [0.75; 1.77]; people with neuropathic bladder or spinal injury (RR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.75 to 1.20) gastrointestinal adverse effects cranberry product vs placebo/no treatment (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.27) |

Cranberry juice or derivates | Placebo or no treatment or any other treatment | |||||

| Knottnerus 2012 (e52) Network MA |

Ia High quality |

UTIs in females >12 yrs Clinical cure (short term): Ciprofloxacin (reference) TMP/SMX 0.71, 0.14-1.49 Norfloxacin 0.63, 0.29-1.39 Nitrofurantoin 0.86, 0.31-2.34 Placebo 0.30, 0.70-1.35 Pivmecillinam 1.39, 0.30-6.46 Amoxicillin-Clavulante 0.07, 0.02-0.24 Gatifloxacin 0.93, 0.68-1.28 Fosfomycin –- Bacteriological cure (short term): Ciprofloxacin (reference) TMP/SMX 0.36, 0.18-0.72 Norfloxacin 0.81, 0.35-1.89 Nitrofurantoin 0.27, 0.11-0.66 Placebo 0.03, 0.01-0.07 Pivmecillinam 0.40, 0.16-0.97 |

Ciprofloxacin | TMP/SMX Norfloxacin Nitrofurantoin Placebo Pivmecillinam Amoxicillin-Clavulante Gatifloxacin Fosfomycin |

|||||

| Amoxicillin-Clavulante 0.17, 0.8-0.35 Gatifloxacin 1.06, 0.79-1.43 Fosfomycin 0.12, 0.03-0.42 Clinical cure (long term): Ciprofloxacin (reference) TMP/SMX 0.87, 0.40-1.89 Norfloxacin 0.91, 0.44-1.90 Nitrofurantoin 1.28, 0.49-3.32 Placebo –- Pivmecillinam –- Amoxicillin-Clavulante 0.31, 0.19-0.53 Gatifloxacin 0.93, 0.71-1.22 Fosfomycin –- Bacteriological cure (long term): Ciprofloxacin (reference) TMP/SMX 0.87, 0.40-1.89 Norfloxacin 0.86, 0.42-1.77 Nitrofurantoin –- Placebo 0,12, 0.05-0.27 Pivmecillinam 0.60, 0.27-1.35 Amoxicillin-Clavulante –- Gatifloxacin 0.96, 0.75-1.22 Fosfomycin –- Adverse effects (OR, CI95%): Ciprofloxacin (reference) TMP/SMX 1.42, [0.60; 3.35] Norfloxacin 1.53, [0.54; 4.31] Nitrofurantoin 1.07, [0.41; 2.78] Placebo 1.24, [0.42; 3.66] Pivmecillinam 1.36, [0.48; 3.89] Amoxicillin-Clavulante 1.55, [0.92; 2.62] Gatifloxacin 1.16, [0.90; 1.49] Fosfomycin –- |

|||||||||

| Kyriakidou 2008 (e53) MA |

Ia Acceptable quality |

Pyelonephritis Clinical success: OR 1.27, CI95% [0.59; 2.70] Bacterial efficacy OR 0.80, CI95% [0.13; 4.94] Relapse OR 0.65, CI95% [0.08; 5.39] Adverse events OR 0.64, CI95% [0.33; 1.25] Recurrence |

Different antibiotics | Short course |

Different antibiotics | Long course | |||

| OR 1.39, CI95% [0.63; 3.06] | |||||||||

| Lutters 2008 (e54) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Lower UTI in elderly Single dose versus short-course treatment: Persistent UTI short term: RR 2.01, CI95% [1.05; 3.84] (5 studies) Persistent UTI long term: RR 1.18, CI95% [0.59; 2.32] (3 studies) Single dose versus long-course treatment: Persistent UTI short term: RR 1.93, CI95% [1.01; 3.70] (6 studies) Persistent UTI long term: RR 1.28, CI95% [0.89; 1.84] (5 studies) Adverse events: RR 0.80, CI95% [0.45; 1.41] (3 studies) short-course versus long-course treatment: Persistent UTI short term (trials comparing the same antibiotic): RR 1.00, CI95% [0.12; 8.57] (2 studies) Persistent UTI long term (trials comparing the same antibiotic): RR 1.18, CI95% [0.50; 2.82] (2 studies) Clinical failure (trials comparing the same antibiotic): RR 0.96, CI95% [0.27; 3.47] (2 studies) Single dose versus short-course or long-course treatment (3 to 14 days): Persistent UTI short term (trials comparing the same antibiotic): RR 1.87, CI95% [0.91; 3.83] (4 studies) Persistent UTI long term (trials comparing the same antibiotic): RR 1.06, CI95% [0.50; 2.24] (2 studies) Adverse events: RR 0.80, CI95% [0.45; 1.41] (3 studies) |

Different antibiotics | Different antibiotics with different treatment duration |

|||||

| Naber 2014 (e55) IPP MA |

Ib | Women with acute uncomplicated cystitis Eradication of bacteriuria (per protocol): Nitroxoline: 184/200 (92.0%) Controls: 197/206 (95.6%) OR: 0.47 CI95% [0.19; 1.14] Clinical efficacy (symptom scoring) in the PP Nitroxoline (n=193) controls (n= 203) (after treatment): Dysuria: p= 0.223 Frequency: p=0.006 Urgency: p=0.030 Nycturia: p=0.254 Flank/back pain: p=0.330 Adverse events, total: Nitroxoline: 23 (9,8%) Controls: 18 (7.8%), p=0.360 |

Nitroxoline | Cotrimoxazole or Norfloxacin of other dosage |

|||||

| Smail 2015 (e56) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy 14 studies (almost 2000 women) Incidence of pyelonephritis: |

Different antibiotics | Placebo or no treatment |

|||||

| Antibiotics reduced the risk: (RR) 0.23, 95%CI [0.13; 0.41]; 11 studies, 1932 women) Incidence of low birthweight babies: RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.93; six studies, 1437 babies) is lower with antibiotics Preterm birth: (RR 0.27, CI95% [0.11; 0.62]; two studies, 242 women) is lower in antibiotics Persistent bacteriuria at the time of delivery (RR 0.30, CI95% [0.18; 0.53]; four studies; 596 women) lower in antibiotics |

|||||||||

| Widmer 2015 (e57) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women 13 studies (1622 women) All were comparisons of single-dose treatment with short-course (4- to 7-day) treatments. Single dose vs short term (4-7 days) (comparing same agent, RR CI95%): No cure: 1.34, [0.85; 2.12] (10 studies) Recurrence: 1.12, [0.76; 1.66] (6 studies) Pyelonephritis: 3.09, [0.54; 17.55] (2 studies) Preterm delivery: 1.17, [0.77; 1.78] (3 studies) Low birth weight: 1.65, [1.06; 2.57] (1 study) Side effects: 0.77, [0.61; 0.97] (9 studies) |

Different antibiotics | Different antibiotics of different duration | |||||

| Vazquez 2011 (e58) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

UTI during pregnancy IV + oral antibiotics versus IV only: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.08, [0.93; 1.27] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 0.47, [0.47; 6.32] IV and oral Cephradine versus IV and oral Cefuroxime: cure (RR, CI95%): 0.75, [0.57; 0.99] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 1.93, [1.03; 3.60] IV Cephazolin versus IV Ampicillin + Gentamicin: |

Different antibiotics | Different antibiotics | |||||

| cure (RR, CI95%): 1.01, [0.93; 1.11] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 1.52, [0.36; 6.47] preterm delivery (RR, CI95%): 1.90, [0.48; 7.55] Intramuscular Ceftriaxone versus IV Ampicillin + Gentamicin: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.05, [0.98; 1.13] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 1.10, [0.23; 5.19] preterm delivery (RR, CI95%): 1.10, [0.23; 5.19] Intramuscular Ceftriaxone versus IV Cephazolin: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.04, [0.97; 1.11] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 0.72, [0.17-; 3.06] preterm delivery (RR, CI95%):0.58, [0.15; 2.29] Oral Ampicillin versus oral Nitrofurantoin: cure (RR, CI95%): 0.97, [0.83; 1.13] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 1.49, [0.55; 4.09] Oral Fosfomycin Trometamol versus oral Ceftibuten: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.06, [0.89; 1.26] Outpatient versus inpatient antibiotics: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.07, [1.00; 1.14] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 1.13, [0.94; 1.35] preterm delivery (RR, CI95%): 0.47, [0.22; 1.02] Cephalosporins once-a-day versus multiple doses: cure (RR, CI95%): 1.02, [0.96; 1.09] recurrence (RR, CI95%): 0.73, [0.17; 3.11] preterm delivery (RR, CI95%): 1.10, [0.44; 2.72] Single versus multiple dose of Gentamicin: cure rate: RR 0.97, CI95% [0.91; 1.03] |

|||||||||

| Zalmanovici Trestioreanu 2010 (e59) Cochrane MA |

Ia High quality |

Asymptomatic bacteriuria 9 studies (1614 participants) Symptomatic UTI: (RR 1.11, CI95% [0.51; 2.43] Complications: (RR 0.78, CI95% [0.35; 1.74] Death: (RR 0.99, CI95% [0.70; 1.41] Bacteriological cure in favor of antibiotics: (RR 2.67, CI95% [1.85; 3.85] Adverse events higher with antibiotics (RR 3.77, CI 95% [1.40; 10.15] |

Different antibiotics | Placebo or no treatment |

|||||

| Minimal data were available on the emergence of resistant strains after antimicrobial treatment. | |||||||||

*Bias-assessment: RCTs via Cochrane Collaboration Tool, cohort studies via SIGN Tool. MA: meta-analysis, SR: systematic review, CI: confidence interval, RR: relative risk, OR: odds Ratio, UTI: urinary tract infections, GP: general practitioner, + high risk, - low risk, ? unclear risk, IV: intravenous.

A guideline synopsis was carried out to identify existing relevant guidelines. The guidelines selected for inclusion (n = 19) were evaluated independently by two authors of the present guideline according to the AGREE criteria (15).

The recommendation grades were decided by the members of the guideline group (see classification in eFigure 2). Evidence-based statements and recommendations were formulated over the course of 17 consensus/telephone conferences. Formal consensus finding took the form of a nominal group process under the leadership of an external moderator from the AWMF (Prof. Kopp). The version of the guideline for consultation was published via the professional societies and on the homepage of the AWMF (10). Comments were discussed by the guideline group and taken into consideration in the final version. The methods, the comments made during the consultation process, and the steps taken to determine conflicts of interest are described in detail in the guideline report (10).

eFigure 2.

The figure depicts the derivation of the recommendation strength from the evidence level. Normally a high level of evidence translates into a strong recommendation. However, provided the grading criteria (consistency of study results, clinical relevance of endpoints, effect size, risk–benefit ratio, and applicability/implementability in the German health care system) are taken into account, the guideline group can up- or downgrade the strength of recommendation (modified from: German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) Standing Guidelines Commission. AWMF Guidance Manual and Rules for Guideline Development, 1st edition 2012. English version. Available at: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk.html (last accessed on July 30, 2017).

The different categories of patients with uUTI ought to be considered separately for purposes of diagnosis, treatment, and prevention:

Non-pregnant women in the premenopause with no relevant comorbidity (standard group)

Pregnant women with no relevant comorbidity

Women in the postmenopause with no relevant comorbidity

Young men with no relevant comorbidity

Patients with diabetes mellitus and stable metabolism with no relevant comorbidity

Results

On the basis of the systematic literature survey, 75 recommendations and 68 statements were agreed upon without discord both by participants with and those without conflicts of interest. The definitions can be found in the Box.

BOX. Definitions used in the S3 guideline on urinary tract infection.

-

Uncomplicated urinary tract infection (uUTI)

A UTI is classed as uncomplicated if no relevant functional or anatomical anomalies in the urinary tract, no relevant renal function disorders, and no relevant comorbities/differential diagnoses are present that could favor a UTI or serious complications.

-

Cystitis

A lower UTI (cystitis) is assumed to be present if the symptoms affect only the lower tract, e.g., newly occurring pain on passing water (alguria), severe urgency, pollakisuria, and pain above the symphysis.

-

Pyelonephritis

An upper UTI (pyelonephritis) ought to be assumed to be present if the acute symptoms include flank pain, renal bed pain on percussion, and/or high temperature (>38 °C).

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB)

In ASB the presence of colonization but not infection is assumed. For reasons of both diagnosis and treatment, it is important to differentiate clinically symptomatic UTI from ASB. Therefore the term “asymptomatic UTI” ought not to be used any longer, because it is unclear and fails to distinguish between the two forms.

-

Recurring urinary tract infection (rUTI)

rUTI is assumed if = 2 symptomatic episodes occur within 6 months, or = 3 symptomatic episodes within 12 months.

In the following, we present selected recommendations on diagnosis (eTable 2, eFigures 3 and 4), treatment (Table 1, Table 2, eFigure 4), and prevention (table 3) for the largest groups of patients (nonpregnant women in the premenopause and pregnant women with no relevant comorbidity). For the other groups of patients defined above, the reader is referred to the long version of the guideline (10).

eTable 2. Reference values for diagnosis of various urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria (e27).

| Diagnosis | Demonstration of bacteria | Urine sampling |

| Acute uncomplicated cystitis in women | 103 CFU/mL | Midstream urine |

| Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis | 104 CFU/mL | Midstream urine |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 105 CFU/mL | ● in women: Demonstration in two consecutive midstream urine cultures ●In men: Demonstration in one midstream urine culture In sampling via catheter and one single bacterial species:10 2 CFU/mL |

CFU, Colony-forming units

eFigure 3.

Decision tree – diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic patients (clinical–microbiological diagnostic pathway),

www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/043–044.html

* On the initial manifestation of acute urinary tract infection, or if the patient is unknown to the physician, the medical history should be documented and a symptom-oriented medical examination carried out.

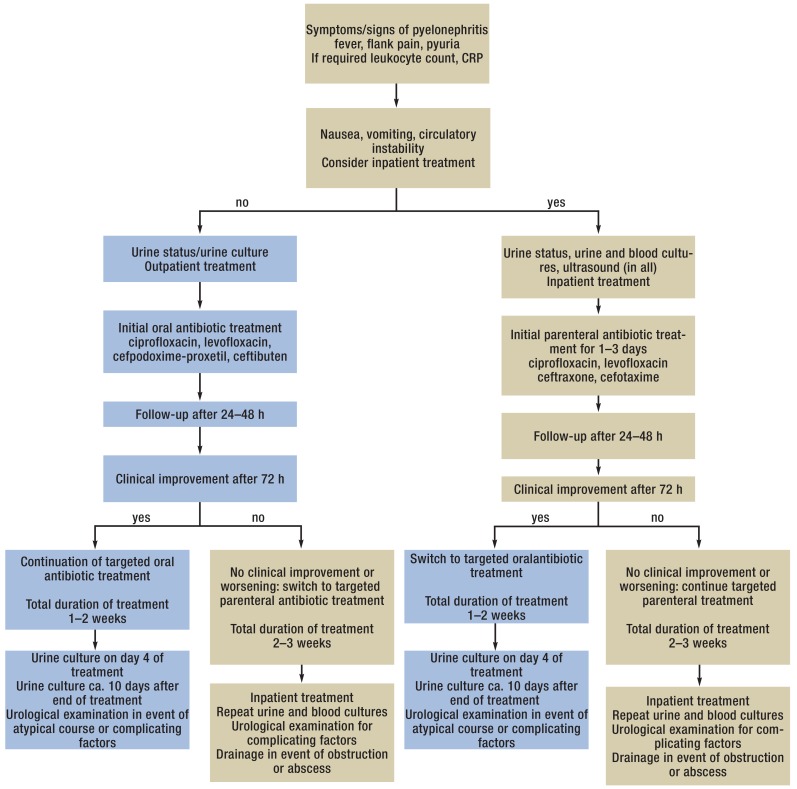

eFigure 4.

Clinical procedure in acute pyelonephritis in adult women,

Table 1. Recommended empirical short-term antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in women in the premenopause (standard group) (listing in alphabetic order).

| Substance | Daily dose | Duration |

Eradication rate in sensitive pathogens |

Sensitivity | Collateral damage |

Safety/adverse drug reactions (ADR) |

| The following antibiotics ought to be used preferentially in the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis: | ||||||

| Fosfomycin- trometamol | 3000 mg 1 × daily | 1 day | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Nitrofurantoin | 50 mg 4 × daily | 7 days | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Nitrofurantoin RT(slow-release form) | 100 mg 2 × daily | 5 days | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Nitroxolin | 250 mg 3 × daily | 5 days | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Pivmecillinam | 400 mg 2–3 × daily | 3 days | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Trimethoprim ought NOT to be used as drug of first choice if local resistance to Escherichia coli is >20%. | ||||||

| Trimethoprim | 200 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | +++ | +(+) | ++ | ++(+) |

| The following antibiotics ought NOT to be used as drugs of first choice in the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis: | ||||||

| Cefpodoxime-proxetil | 100 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| Ciprofloxacin | 250 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Cotrimoxazole | 160/800 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | +++ | +(+) | ++ | ++ |

| Levofloxacin | 250 mg 1 × daily | 3 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Norfloxacin | 400 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Ofloxacin | 200 mg 2 × daily | 3 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Symbol | Eradication | Sensitivity | Collateral damage | Safety/UAW | ||

| +++ | >90% | >90% | Little selection of multiresistant pathogens, little development of resistance to own class of antibiotics | High safety, slight ADR | ||

| ++ | 80–90% | 80–90% | Little selection of multiresistant pathogens, development of resistance to own class of antibiotics | Severe ADR possible | ||

| + | <80% | <80% | Selection of multiresistant pathogens, development of resistance to own class of antibiotics | n.a. | ||

ADR, adverse drug reactions; n.a., not available

Table 2. Recommended empirical short-term antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated pyelonephritis in women in the premenopause (standard group) (listing in alphabetic order).

| Substance | Daily dose | Duration | Eradication rate in sensitive pathogens | Sensitivity |

Collateral damage |

Safety/adverse drug reactions (ADR) |

| Oral treatment in mild to moderate disease | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin*1 | 500–750 mg 2 × daily | 7–10 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Levofloxacin | 750 mg 1 × daily | 5 days | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Cefpodoxime-proxetil | 200 mg 2 × daily | 10 days | +++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| Ceftibuten*2 | 400 mg 1 × daily | 10 days | +++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| Initial parenteral treatment in severe disease | ||||||

| Following improvement, in the presence of pathogen sensitivity oral sequential treatment with one of the above-mentioned oral agents can be initiated. The total duration of treatment is 1–2 weeks; therefore, no duration of treatment is given for the parenteral antibiotics. | ||||||

| First-choice drugs | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 400 mg (2)–3 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | |

| Levofloxacin | 750 mg 1 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | |

| Ceftriaxone*1, *3 | (1)–2 g 1 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | |

| Cefotaxime*4 | 2 g 3 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | |

| Second-choice drugs | ||||||

| Amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid*4, *5 | 2.2 g 3 × daily | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Amikacin | 15 mg/kg 1 × daily | ++ | ++ | ++ | +(+) | |

| Gentamicin | 5 mg/kg 1 × daily | ++ | ++ | ++ | +(+) | |

| Cefepime*1, *3 | (1)–2 g 2 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | |

| Ceftazidime*4 | (1)–2 g 3 × daily | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 2.5 g 3 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 1.5 g 3 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Piperacillin/ tazobactam*1, *3 | 4.5 g 3 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Ertapenem*3, *6 | 1 g 1 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Imipenem/cilastatin*1, *3, *6 | 1 g/1g 3 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Meropenem*3, *6, *7 | 1 g 3 × daily | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | |

*1 Low dosage investigated, high dosage recommended by experts; *2 no longer on sale in Germany; *3 same protocol for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis and complicated urinary tract infection (stratification not always possible); *4 not investigated as sole substance in acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis; *5 principally for Gram-positive pathogens;

*6 only in extended-spectrum betalactamase resistance >10%; *7 only high dosages investigated; symbols as explained in Table 1

Table 3. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis of recurring urinary tract infection (after [31]).

| Substance | Dosage |

Anticipated UTI rate per patient year |

Sensitivity |

Collateral damage |

Safety/adverse drug reactions (ADR) |

| Continuous long-term prophylaxis | |||||

| Cotrimoxazole | 40/200 mg 1 × daily | 0–0.2 | +(+) | ++ | ++ |

| Cotrimoxazole | 40/200 mg 3 × weekly | 0.1 | +(+) | ++ | ++ |

| Trimethoprim | 100 mg 1 × daily*1 | 0–1.5 | +(+) | ++ | +++ |

| Nitrofurantoin | 50 mg 1 × daily | 0–0.6 | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Nitrofurantoin | 100 mg 1 × daily*2 | 0–0.7 | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Cefaclor | 250 mg 1 × daily*3 | 0.0 | n.d. | + | +++ |

| Cefaclor | 125 mg 1 × daily*3 | 0.1 | n.d. | + | +++ |

| Norfloxacin | 200 mg 1 × daily*3 | 0.0 | ++ | + | ++ |

| Ciprofloxacin | 125 mg 1 × daily*3 | 0.0 | ++ | + | ++ |

| Fosfomycin- trometamol | 3 g every 10 days | 0.14 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Postcoital single-dose prophylaxis | |||||

| Cotrimoxazole | 40/200 mg | 0.3 | +(+) | ++ | ++ |

| Cotrimoxazole | 80/400 mg | 0.0 | +(+) | ++ | ++ |

| Nitrofurantoin | 50 mg | 0.1 | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Nitrofurantoin | 100 mg*2 | 0.1 | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Cefalexin | 250 mg*3 | 0.0 | n.d. | + | +++ |

| Cefalexin | 125 mg*3 | 0.0 | n.d. | + | +++ |

| Norfloxacin | 200 mg*3 | 0.0 | ++ | + | ++ |

| Ofloxacin | 100 mg*3 | 0.03 | ++ | + | ++ |

*1In older studies, trimethoprim 50 mg was reported as equieffective to 100 mg; *2in the case of equieffectiveness, nitrofurantoin 50 mg is the dose of choice; *3to avoid collateral damage and above all increasing resistance; use only if the other substances cannot be used.

n.d., No data

Symbols as explained in Table 1

Diagnosis

The diagnostic techniques are intended to establish whether a UTI is present and, in some cases, to identify the pathogen responsible for the infection and to determine how it can be treated.

Confirmation of acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC) on clinical criteria alone is afflicted by an error rate of up to one third (16, 17). The only way of reducing diagnostic inaccuracy would be always to perform a urine culture with determination of all pathogens, even those present in low counts (gold standard). However, pursuing this maximal strategy in nonselected patients is neither economically reasonable (18) nor practicable in daily routine, because the delay before the results of a urine culture are known means that they would have no essential influence on the empirical short-term treatment.

Diagnosis in the standard group: nonpregnant women in the premenopause

Acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC)—There is a probability of almost 80% that women who have no risk factors for complicated UTI, complain of typical symptoms (pain on passing water, pollakisuria, severe urgency), have no vaginal symptoms (itchiness, altered secretions), and deny fever and flank pain will have AUC (e1, e2) (evidence level IIa). A urine culture is unnecessary in women with clear-cut clinical symptoms of uncomplicated, nonrecurrent or non-treatment-resistant cystitis. In a first manifestation of AUC, or if the patient is unknown to the physician, the medical history ought to be taken and a symptom-related medical examination carried out (evidence level V-B). With the validated Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) questionnaire (efigure 5), AUC can be diagnosed with a high degree of certainty based on clinical criteria (94.7% sensitivity and 82.4% specificity with a total score of = 6 points), the severity of the symptoms can be estimated, the patient’s progress can be followed, and the treatment effect is rendered measurable (evidence level IIb) (19, 20).

eFigure 5.

British version of the ACSS questionnaire on the clinical diagnosis of acute, uncomplicated cystitis in women: Part A (first visit)

(The questionnaire is available for download in multiple languages at www.acss.world).

Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (AUP)—In addition to establishing the patient’s general medical history, physical examination and urinalysis including urine culture should be carried out (evidence level V-A). Moreover, further investigations (e.g., sonography) should be considered with the goal of excluding complicating factors (evidence level V-A) (e3).

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB)—It is strongly recommended that no screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria be performed in nonpregnant women with no relevant comorbidity (evidence level Ia-A) (e4– e6).

Recurring urinary tract infection (rUTI)—In patients with rUTI, urine ought to be cultured and sonography ought to be performed once only. No other invasive diagnostic tests ought to be carried out (evidence level Ib-B) (e7, e8). In patients with persisting hematuria or persisting presence of pathogens other than E. coli, urethrocystoscopy and further imaging are recommended (evidence level V-B) (e2, e9, e10).

Diagnosis in pregnant women without relevant comorbidity

Acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC)—The patient’s medical history ought to be taken just as in nonpregnant patients, but physical examination and urinalysis including urine culture are strongly recommended (evidence level V-A). Following the antibiotic treatment of AUC in pregnancy, eradication of the pathogen should be verified by urine culture (evidence level V-A).

Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis (AUP)—The diagnosis of AUP in pregnant women is analogous to that in nonpregnant patients (evidence level V). Physical examination and urinalysis including urine culture are mandatory (evidence level V-A). If pyelonephritis is suspected, sonography of the kidneys and urinary tract should be carried out (evidence level V-A) (e11, e12). Following the antibiotic treatment of pyelonephritis in pregnancy, eradication of the pathogen should be verified by urine culture (evidence level V-A).

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB)—Systematic screening for ASB ought not to be carried out in pregnant women (EG Ib-B) (21, e13– e18). The strip tests generally used for this purpose have low sensitivity (14 to 50%) for ASB in pregnancy (21– 23).

Use of strip tests alone is inadequate for diagnosis of ASB in pregnancy (evidence level IV) (21– 23).

Recurring urinary tract infection (rUTI)—The diagnostic work-up in pregnant women without relevant comorbidity broadly corresponds to that in young women with no relevant comorbidity.

An overview of the reference values for the diagnosis of various UTIs and ASB can be found in eTable 2.

Treatment

The following criteria should be taken into account when deciding which antibiotic to use (evidence level Ia-A):

The patient’s individual risk

The spectrum of pathogens and antibiotic sensitivity

The efficacy of the antimicrobial substance

The adverse drug reactions

The effects on the resistance situation in the individual patient (collateral damage) and/or the general population (epidemiological effects)

Acute uncomplicated cystitis: standard group

The spontaneous recovery rate in AUC is high (at 1 week: clinically 28%, clinically and microbiologically 37%). The central goal of treatment is swift relief of the clinical symptoms, i.e., within a matter of days (24). The small number of placebo-controlled studies performed have shown that the symptoms resolve more rapidly with antibiotic treatment than with placebo (25). In a recent study, Gágyor et al. compared the effect of primarily symptomatic ibuprofen treatment with that of immediate administration of an antibiotic. Around two thirds of patients with purely symptomatic treatment needed no further antibiotic (26). In light of these findings, nonantibiotic, symptomatic treatment may be considered in cases of AUC with mild or moderate symptoms (evidence level IA-B). Due consideration should be paid to the patients’ preferences when deciding what course of treatment to follow. This is especially true for primarily nonantibiotic treatment, which may be associated with a greater burden of symptoms (freedom from symptoms after 7 days: ibuprofen 163/232 patients versus fosfomycin 186/227 patients, 95% confidence interval [-19.4; -4.0]) (26). The decision should be made together with the patient.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

The presence of ASB increases the risk of infection for patients undergoing urinary tract interventions in which mucosal trauma can be anticipated. For this reason ASB should be actively sought in such cases, and if found it should be treated (evidence level IA-A) (27).

The evidence from randomized studies in this respect is primarily for transurethral resection of the prostate. There is no evidence regarding low-risk interventions, e.g., urethrocystocopy.

Kazemier et al. showed that in women with low risk pregnancy and ASB the risk of symptomatic cystitis increased from 7.9% to 20.2% if they were treated with placebo or not at all (for pyelonephritis from 0.6% to 2.4%) (28). However, ASB did not increase the risk of premature birth for nontreated patients in this low risk pregnancy population (28).

General comment on antibiotic treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis

Among the group of antibiotics or classes of antibiotic drugs that are basically suitable for the treatment of AUC—aminopenicillins in combination with a betalactamase inhibitor, group 2 and 3 cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, fosfomycin-trometamol, nitrofurantoin, nitroxolin, pivmecillinam, trimethoprim or cotrimoxazole—the fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins are associated with the greatest risk of microbiological collateral damage in the form of selection of multiresistant pathogens and development of Clostridium difficile-associated colitis (29).

Since fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins have an important role in complicated infections, the clinical consequences of increased resistance by using them in uncomplicated infections was rated as more severe than for other antibiotics recommended for the treatment of AUC. (evidence level V). It is thus strongly recommended that the fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins are not used in the treatment of AUC unless there is a contraindication for alternative substances (evidence level V-A) (table 1). In addition, patient-relevant clinical endpoints (clinical improvement of symptoms, recurrences, ascending infections) and the individual risk (e.g., Achilles tendon rupture with the fluoroquinolones) should be taken into account.

Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis: standard group

Patients with AUP should receive efficacious antibiotic treatment as soon as possible, because kidney damage (30), though not frequent, is more likely with increasing duration, severity, and frequency of such infections. In choosing the best antibiotic, the eradication rates, sensitivity, collateral damage, and special characteristics with regard to adverse drug reactions should be taken into account (evidence level V) (Table 2, eFigure 4). Because the prevalence is much lower than that of AUC (0.16%) (1), less heed has to be paid to collateral damage (1).

Prevention of recurring urinary tract infection: standard group

Before initiation of long-term prophylactic drug treatment, a woman with rUTI should be counseled in detail on avoidance of risks (e.g., not drinking enough, overcooling, excessive intimate hygiene) (evidence level Ib-A) (e19, e20). If appropriate preventive measures have been taken but rUTI persists, long-term antibiotic prophylaxis ought to be preceded by oral administration of an E. coli lysate (OM-89) for 3 months (evidence level Ia-B) (e21). Immunoprophylaxis by means of three parenteral injections of inactivated specified enterobacteria at 1-week intervals may be considered (evidence level Ib-C) (28). Moreover, mannose may be considered (e22); alternatively, various phytotherapeutic agents may be considered (evidence level Ib-C) (e23, e24). If the patient’s level of suffering is high, failure of behavioral modification and nonantibiotic prophylaxis ough to be followed by continual long-term antibiotic prophylaxis for 3 to 6 months (evidence level IV-B) (31) (table 3). In the presence of an association with sexual intercourse, postcoital prophylaxis with a single dose ought to be used instead of long-term administration of antibiotics (evidence level Ib-B) (31, e25, e26).

Conclusion

The high frequency of uncomplicated bacterial community-acquired urinary tract infections in adults and their treatment with antibiotics exerts massive antibiotic selection pressure on the bacteria involved and also on the collateral flora, resulting in significant influence on the selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the population. Careful use of antibiotics for this indication is therefore extremely important in safeguarding the efficacy of antibiotic treatment. The treatment recommendations were thus crucially influenced by considerations of antibiotic stewardship. The evidence- and consensus-based recommendations of the updated S3 guideline therefore need to be widely implemented by all categories of medical professionals entrusted with the treatment of urinary tract infections in order to improve the standards of care and ensure a forward-looking policy on the use of antibiotics.

Key Messages.

High value is attached to symptom-oriented diagnosis. By means of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) questionnaire, acute uncomplicated cystitis can be diagnosed with a high degree of certainty based on clinical criteria, the severity of the symptoms can be estimated, the patient’s progress can be followed, and the treatment effect is rendered measurable.

In uncomplicated urinary tract infections with mild to moderate symptoms, symptomatic treament with ibuprofen presents an alternative to the prescription of antibiotics.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria ought not to be treated. Only in patients undergoing urinary tract interventions in which mucosal trauma can be anticipated does asymptomatic bacteriuria increase the risk of infection. Therefore asymptomatic bacteriuria should be actively sought in such cases, and if found it should be treated

Primarily nonantibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for recurring urinary tract infections.

Considerations of antibiotic stewardship crucially influenced the treatment recommendations. Broad implementation of the new recommendations by all groups of medical professionals treating urinary tract infections is necessary to ensure a forward-looking policy on the use of antibiotics and thus to improve the standards of care.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Acknowledgments

International reviewer: Gernot Bonkat (Switzerland)

Coordination and external moderation: Ina Kopp, AWMF Institute for Medical Knowledge Management, University of Marburg

We are especially grateful to Alexandra Pulst, scientific assistant at the Department of Care Research, Institute for Public Health and Nursing Care Research, University of Bremen for her support in compiling the guideline synopsis and evidence assessment.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Wagenlehner has received consultancy fees from Achaogen, Astra Zeneca, Bionorica, MSD, Pfizer, Rosen Pharma, Vifor Pharma, and Leo Pharma. Furthermore, he has received funds to conduct clinical studies from MSD, Pfizer, Vifor Pharma, Rosen Pharma, and Leo Pharma.

Dr. Kranz has received funds to carry out a systematic review from Leo Pharma.

Dr. Schmidt has received funds to carry out a systematic review from Leo Pharma.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Dicheva S. Glaeske G, Schicktanz C, editors. Harnwegsinfekte bei Frauen. Barmer GEK Arzneimittelreport. 2015:107–137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson CC. Definitions, classification, and clinical presentation of urinary tract infections. Med Clin North Am. 1991;75:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai T, Verze P, Brugnolli A, et al. Adherence to European Association of urology guidelines on prophylactic antibiotics: an important step in antimicrobial stewardship. Eur Urol. 2016;69:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, Ma LY, Zhao X, Tian SH, Sun LY, Cui YM. Impact of pharmacist intervention on antibiotic use and prophylactic use in urology clean operations. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40:404–408. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagenlehner FME, Bartoletti R, Cek M, et al. Antibiotic stewardship: a call for action by the urologic community. Eur Urol. 2013;64:358–360. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niersächisches Gesundheitsamt. ARMIN. www.nlga.niedersachsen.de/infektionsschutz/armin_resistenzentwicklung/armin_inter aktiv/ (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naber KG, Schito GC, Botto H, Palou J, Mazzei T. Surveillance study in Europe and Brazil on clinical aspects and antimicrobial resistance epidemiology in females with cystitis (ARESC): Implications for empiric therapy. European Urology. 2008;54:164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwirner M, Bialek R, Roth T, et al. Local resistance profile of bacterial isolates in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (LORE study) Kongressabstract DGHM. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) Standing Guidelines Commission. AWMF Guidance Manual and Rules for Guideline Development, 1st edition 2012 English version. Available at: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk.html (last accessed on July 30, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leitlinienprogramm DGU. Interdisziplinäre S3 Leitlinie: Epidemiologie, Diagnostik, Therapie, Prävention und Management unkomplizierter, bakterieller, ambulant erworbener Harnwegsinfektionen bei erwachsenen Patienten. Langversion 1.1-2, 2017 AWMF Registernummer: 043/044. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/043-044.html (last accessed on 12 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) www.prisma-statement.org (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Healthcare Improvement Scotland. www.sign.ac.uk/checklists-and-notes.html (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Cochrane Collaboration. www.handbook.cochrane.org/ chapter_8/table_8_5_d_criteria_for_judging_risk_of_ bias_in_the_risk_of.htm (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centre for evidence based Medicine (CEBM) www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/ (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) www.agreetrust.org/ (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, ter Riet G, Toward A. Simple diagnostic index for acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Ann Fam Med. 2013:442–451. doi: 10.1370/afm.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, et al. Developing clinical rules to predict urinary tract infection in primary care settings: sensitivity and specificity of near patient tests (dipsticks) and clinical scores. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:606–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothberg MB, Wong JB. All dysuria is local A cost-effectiveness model for designing sitespecific management algorithms. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.10440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alidjanov JF, Pilatz A, Abdufattaev UA, et al. [German validation of the acute cystitis symptom score] Urologe A. 2015;54:1269–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00120-015-3873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alidjanov JF, Lima HA, Pilatz A, et al. Preliminary Clinical Validation of the English Language Version of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score. JOJ uro & nephron. 2017;1 555561. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachman JW, Heise RH, Naessens JM, Timmerman MG. A study of various tests to detect asymptomatic urinary tract infections in an obstetric population. JAMA. 1993;270:1971–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumbiganon P, Chongsomchai C, Chumworathayee B, Thinkhamrop J. Reagent strip testing is not sensitive for the screening of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85:922–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tincello DG, Richmond DH. Evaluation of reagent strips in detecting asymptomatic bacteriuria in early pregnancy: prospective case series. BMJ. 1998;316:435–437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferry SA, Holm SE, Stenlund H, Monson TJ. The natural course of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women illustrated by a randomized placebo controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:296–301. doi: 10.1080/00365540410019642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christiaens TC, de Meyere M, Verschraegen G, Peersman W, Heytens S, de Maeseneer JM. Randomised controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:729–734. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gágyor I, Bleidorn J, Kochen MM, Schmiemann G, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Ibuprofen versus fosfomycin for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6544. h6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:643–654. doi: 10.1086/427507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazemier BM, Koningstein FN, Schneeberger C, et al. Maternal and neonatal consequences of treated and untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a prospective cohort study with an embedded randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1324–1333. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.S3-Leitlinie Strategien zur Sicherung rationale Antibiotika-Anwendung im Krankenhaus AWMF-Registernummer 092/001. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/092-001.html (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frei U Schober-Hasltenberg. Nierenersatztherapie in Deutschland. Bericht über Dialysebehandlung und Nierentransplantation in Deutschland 2006/2007. www.bundesverband-niere.de/fileadmin/user_upload/QuaSi-Niere-Bericht_2006-2007.pdf (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund Johansen TE, et al. Guidelines on urological infections EAU Guidelines 2015. www.uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E1.Christiaens T, Callewaert L, de Sutter A, van Royen P. Aanbeveling voor goede medische praktijkvoering: cystitis bij de vrouw. Huisarts nu: maandblad van de Wetenschappelijke Vereniging van Vlaamse Huisartsen. 2000;29:282–288. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Epp A, Larochelle A. SOGC clinical practice guideline: recurrent urinary tract infection. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010:1082–1090. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34717-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.van Nieuwkoop C, Hoppe BP, Bonten TN, et al. Predicting the need for radiologic imaging in adults with febrile urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1266–1272. doi: 10.1086/657071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: review and discussion of the IDSA guidelines. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;(28):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when to screen and when to treat. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:367–394. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 88 management of suspected bacterial urinary tract infection in adults. 2012. www.sign.ac.uk/sign-88-management-of-suspected-bacterial-urinary-tract-infection-in-adults.html (last accessed on 12 November 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E7.Parsons SR, Cornish NC, Martin B, Evans SD. Investigation of uncomplicated recurrent urinary tract infections in women. J Clin Urol. 2016;4:234–238. [Google Scholar]

- E8.Wagenlehner FME, Wagenlehner C, Savov O, Gulaco L, Schito G, Naber KG. Klinik und Epidemiologie der unkomplizierten Zystitis bei Frauen. Urologe. 2010;49:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s00120-009-2145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.van Pinxteren B, Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, et al. De standaard en wetenschappelijke verantwoording zijn geactualiseerd ten opzichte van de vorigeversie. Huisarts Wet. 2005;8:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- E10.American Urological Association. Diagnoses, evaluation and follow up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults. www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/asymptomatic-microhematuria.cfm (last accessed on 7 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E11.McDermott S, Callaghan W, Szwejbka L, Mann H, Daguise V. Urinary tract infections during pregnancy and mental retardation and developmental delay. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.McDermott S, Daguise V, Mann H, Szwejbka L, Callaghan W. Perinatal risk for mortality and mental retardation associated with maternal urinary-tract infections. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Delzell JE, Lefevre ML. Urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Force U. Guide to clinical preventive services: report of the US. Preventive Service Task Force. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- E15.McNair RD, MacDonald SR, Dooley SL, Peterson LR. Evaluation of the centrifuged and gram-stained smear, urinalysis, and reagent strip testing to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria in obstetric patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1076–1079. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Millar L, DeBuque L, Leialoha C, Grandinetti A, Killeen J. Rapid enzymatic urine screening test to detect bacteriuria in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:601–604. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Ovalle A, Levancini M. Urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;11:55–59. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Santos JF, Ribeiro RM, Rossi P, et al. Urinary tract infections in pregnant women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13:204–209. doi: 10.1007/s192-002-8354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Lumsden L, Hyner GC. Effects of an educational intervention on the rate of recurrent urinary tract infection. Women & Health. 1985;10/1:79–86. doi: 10.1300/J013v10n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Su SB, Wang JN, Lu CW, Guo HR. Reducing urinary tract infections among female clean room workers. J Womens Health. 2006;15/7:870–876. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Beerepoot MA, Geerlings SE, van Haarst EP, van Charante NM, ter Riet G. Nonantibiotic prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Urol. 2013;190:1981–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Albrecht U, Goos KH, Schneider B. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a herbal medicinal product containing tropaeoli majoris herba (nasturtium) and armoraciae rusticanae radix (horseradish) for the prophylactic treatment of patients with chronically recurrent lower urinary tract infections. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23/10:2415–2422. doi: 10.1185/030079907X233089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Kranjcec B, Papes D, Altarac S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial. World J Urol. 2014;32:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Larsson B, Jonasson A, Fianu S. Prophylactic effect of UVA-E in women with recurrent cystitis: a preliminary report. Curr Ther Res. 1993;53/4:441–443. [Google Scholar]

- E25.Melekos MD, Asbach H, Gerharz E, Zarakovitis I, Weingärtner K, Naber K. Postintercourse versus daily ciprofloxacin prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women. J Urol. 1997;101:935–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Pfau A, Sacks TG. Effective postcoital prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in premenopausal women: a review. Int Urogynecol J. 1991;2:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- E27.Rubin RH, Shapiro ED, Andriole VT, Davis RJ, Stamm WE. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infection Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug Administration. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(1):216–227. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.supplement_1.s216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Bleidorn J, Gágyor I, Kochen MM, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Symptomatic treatment (ibuprofen) or antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) for uncomplicated urinary tract infection?—results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Med. 2010;8 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Ceran N, Mert D, Kocdogan FY, et al. A randomized comparative study of single-dose fosfomycin and 5-day ciprofloxacin in female patients with uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections. J Infect Chemother. 2010;16 doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0079-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Stapleton AE. Cefpodoxime vs ciprofloxacin for short-course treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Palou J, Angula JC, Ramón de Fata F, et al. [Randomized comparative study for the assessment of a new therapeutic sched-ule of fosfomycin trometamol in postmenopausal women with uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection] Actas Urol Esp. 2013;37:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]