Abstract

Oncolytic viruses (OV) are an emerging class of anticancer bio-therapeutics that induce antitumor immunity through selective replication in tumor cells. However, the efficacy of OVs as single agents remains limited. We introduce a strategy that boosts the therapeutic efficacy of OVs by combining their activity with immuno-modulating, small molecule protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. We report that vanadium-based phosphatase inhibitors enhance OV infection in vitro and ex vivo, in resistant tumor cell lines. Furthermore, vanadium compounds increase antitumor efficacy in combination with OV in several syngeneic tumor models, leading to systemic and durable responses, even in models otherwise refractory to OV and drug alone. Mechanistically, this involves subverting the antiviral type I IFN response toward a death-inducing and pro-inflammatory type II IFN response, leading to improved OV spread, increased bystander killing of cancer cells, and enhanced antitumor immune stimulation. Overall, we showcase a new ability of vanadium compounds to simultaneously maximize viral oncolysis and systemic anticancer immunity, offering new avenues for the development of improved immunotherapy strategies.

Keywords: oncolytic virus, VSV, STAT, type I interferon, type II interferon, vanadate, vanadium, T cell activation, immunotherapy, CXCL9

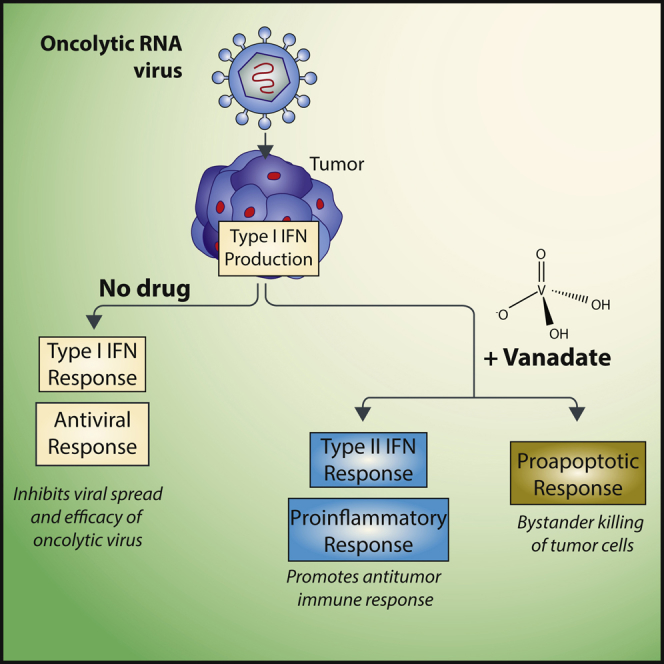

Graphical Abstract

Efficacy of oncolytic viruses as single agents remains limited. Selman et al. show that vanadium-containing phosphatase inhibitors increase infection and efficacy of oncolytic RNA viruses via the suppression of the type I Interferon response leading to the promotion of a death-inducing and pro-inflammatory type II Interferon response.

Introduction

Oncolytic viruses (OV) are an emerging class of anticancer bio-therapeutics that selectively replicate in and lyse tumor cells, without causing damage to normal cells.1, 2 Multiple OVs have shown efficacy in pre-clinical models of cancer and in clinical trials.2 Notably, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have recently approved T-VEC (Imlygic) for the treatment of melanoma. While OVs can lead to profound anticancer responses as single agents, clinical data show that some patients do not respond to OVs alone and may benefit from combination therapies.3, 4, 5

Poor infection of tumors is an important factor in the resistance to OV therapy. OV spread, oncolysis, and overall therapeutic efficacy can be improved in resistant tumors among others by using pharmacological compounds that block the cellular innate antiviral immune response mediated by type I interferon (IFN).6, 7, 8, 9 Beyond direct effects on tumor cells, OVs can remodel the tumor microenvironment and boost antitumor immunity by directing immune responses to the tumor niche.10, 11, 12, 13 This immunostimulatory effect can be enhanced by integrating immune stimulatory genes into the viral genome14, 15 or by combination with other forms of immunotherapy such as immune checkpoint inhibitors.16, 17, 18, 19

Vanadate and other vanadium-based compounds are pan-inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatases, with a wide range of biological effects.20, 21 Clinically, these compounds have been mostly explored for their antidiabetic potential, demonstrating safety for this indication in phase I/II human trials.22, 23 In more recent years, a number of vanadium compounds were also found to exhibit anticancer effects in animal models.24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Numerous studies suggest that vanadium compounds impact the immune system,32, 33, 34, 35 for example by stimulating and activating T cells.33 However, the mechanism by which vanadium-based compounds can modulate anticancer immunity has not been investigated.

Given their potential immunostimulatory effects, we assessed the use of selected vanadium compounds as complementary pharmacological agents to OV-mediated immunotherapy. Here, we demonstrate an unprecedented ability of these compounds to subvert the type I IFN antiviral response toward a death-inducing and pro-inflammatory type II IFN response, culminating in the dramatically improved anticancer activity of OVs both in vitro and in vivo.

Results

Vanadate Enhances the Spread of Oncolytic RNA Viruses

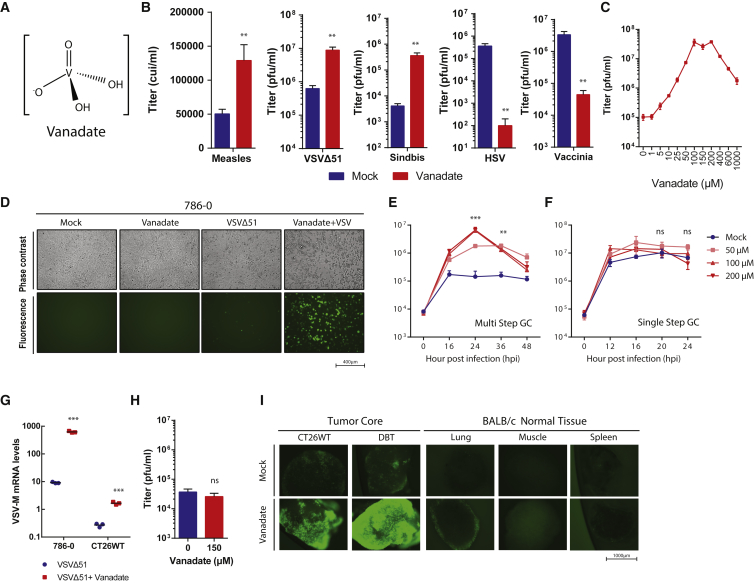

Contrasting results have been reported in the few studies that have probed the effect of vanadate (Figure 1A) on viral infection.36, 37 To explore this in the context of OVs, we tested the impact of orthovanadate on the growth of a small panel of candidate OVs. We included negative single-strand RNA viruses vesicular stomatitis virus (VSVΔ51)38 and measles (Schwarz strain),39 a positive single-strand RNA virus (sindbis), as well as double-stranded DNA viruses herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1 mutant N212)40 and vaccinia virus (deleted for thymidine kinase and expressing GM-CSF)41 (Figure 1B). We found that the growth of RNA viruses including measles, sindbis, and oncolytic VSVΔ51, but not DNA viruses HSV-1 and vaccinia, was enhanced by treatment with vanadate. VSVΔ51 growth was most robustly enhanced, and further testing in VSV-resistant 786-0 renal carcinoma cells revealed that vanadate increased viral output, as measured by plaque assay, up to ∼400-fold over a 10–1,000 μM dose range (Figure 1C), which was below the median lethal concentration of vanadate (Figure 3A). Use of a GFP-expressing VSVΔ51 revealed a corresponding increase in the number of GFP-positive infected cells (Figure 1D). A similar impact on viral infection was observed in various human and murine cancer cell lines (Figures S1A and S1B). Single- and multi-step growth curves in 786-0 cells revealed that vanadate more robustly enhanced the yield of VSVΔ51 at a low MOI compared to a high MOI, indicating that vanadate promotes viral spread (compare Figures 1E and 1F). Similarly, in the presence of vanadate, VSVΔ51 produced larger plaques, based on both the area of GFP-positive cells as well as the cytopathic effect observed upon Coomassie blue staining (Figure S2). The impact of vanadate on viral growth was more pronounced with increasing pre-treatment time (maximum tested 24 hr), with the effect of vanadate being negligible when provided later than 12 hr post-infection (Figure S1C). Similarly, treatment with vanadate after infection reduced its negative effect on vaccinia infection but did not lead to enhancement (Figure S1D). Correlating with viral titers and GFP expression data, Figure 1G shows that vanadate increased the production of VSVΔ51 genomes in infected 786-0 cells as well as in mouse CT26WT colon cancer cells. In contrast, viral growth was not enhanced in normal adult human GM38 fibroblasts (Figure 1H). Using mouse tissue cores obtained from normal lung, muscle, spleen, and tumor tissues obtained from mice implanted with CT26WT and DBT (glioma) cells, we further evaluated the impact of vanadate on growth of VSVΔ51-GFP. Fluorescence microscopy images in Figure 1I show that vanadate preferentially increased the growth of the virus in tumor cores with no impact on normal tissues.

Figure 1.

Vanadate Enhances VSVΔ51 Infection in Cancer Cells but Not Normal Cells

(A) Structure of vanadate ion present at pH 7.4. (B–F and H) Resistant 786-0 human renal cancer cells were pre-treated with vanadate for 4 hr and subsequently infected with (B–E and H) VSVΔ51 (MOI, 0.01 [150 μM]), (B) measles (MOI, 0.01 [100 μM]), (B) sindbis (MOI, 10 [150 μM]), (B) HSV (MOI, 0.01 [150 μM]), (B) vaccinia (MOI, 0.01 [200 μM]). (B and C) Corresponding viral titers were determined 24 (VSVΔ51) or 48 (measles, sindbis, HSV, vaccinia) hr post-infection (hpi) from supernatants. (B, G, and H) n = 3; error bars indicate SEM; t test; NS, no statistical significance; **p < 0.001; as compared to the untreated condition counterparts; (C) n = 3; significance enhancement at 100–200 μm; p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; as compared to 0 μm condition). (D) Twenty-four hours post-infection, fluorescent and phase contrast images were taken of the 786-0 cells treated with mock or 200 μM of vanadate. (E) Multi-step and (F) single-step growth curve of 786-0 pre-treated with vanadate and infected with VSVΔ51 (E) MOI 0.01 or (F) MOI 3; supernatants were tittered by plaque assay (n = 3; significant enhancement at 50–200 μm at indicated time; NS, no statistical significance; **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA; as compared to mock condition). (G) Twenty-four hours post-infection, RNA was collected from 786-0 and CT26WT, and expression of VSV-M gene was quantified by qPCR. (H) Normal cell line GM38 was pre-treated as in (B) infected with VSVΔ51. Corresponding viral titers were determined 24 hpi from supernatants. (I) CT26WT and DBT tumor cores and BALB/c mouse spleen, muscle, lung, and brain tissue cores were pre-treated with 300 μM of vanadate for 4 hr and subsequently infected with 1 × 104 PFU of VSVΔ51 expressing GFP. Twenty-four hours post-infection, fluorescent images were acquired of the tumor and normal tissue cores. Representative images from each triplicate set are shown.

Figure 3.

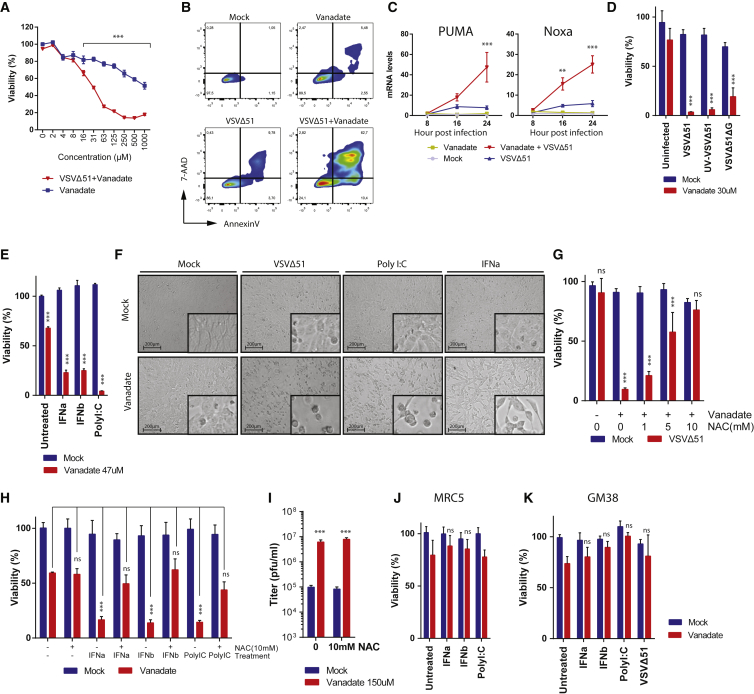

Vanadate Facilitates Virus-Induced Type I Interferon and ROS-Mediated Cell Death

(A) 786-0 cells were pre-treated with a range of concentrations of vanadate for 4 hr and were subsequently infected with VSVΔ51 expressing GFP at an MOI of 0.01. 786-0 cell viability was assayed in cells 24 hr post-infection. Results were normalized to the average of the values obtained for the corresponding uninfected, untreated cells (n = 4; error bars indicate SEM; significance decrease in viability at 16–1,000 μm; ***p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA; as compared to uninfected condition). (B) 786-0 were pre-treated with vanadate (100 μM) for 4 hr and subsequently infected with oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing GFP at an MOI of 0.01. Twenty-four hours post-infection, induction of cell death was determined by annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining. Numbers indicate the percentage in each quadrant. (C) Cell lysates of 786-0 treated with vanadate (100 μM) and VSVΔ51 expressing GFP were collected at indicated time points, RNA was collected, and expression of PUMA and Noxa genes was quantified by qPCR (n = 3; error bars indicate SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA; comparing VSVΔ51 condition to vanadate + VSVΔ51 condition). (D and E) 786-0 cells were pre-treated with vanadate for 4 hr and subsequently infected with (D) VSVΔ51, UV-inactivated VSVΔ51, VSVΔ51ΔG, or (E) treated with IFNa, IFNb, or Poly I:C. Cell viability was assayed 48 hr post-infection or treatment. Corresponding cell morphology is presented in (F). (G–I) 786-0 cells were co-treated with vanadate and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) for 4 hr and infected with (G–I) VSVΔ51 expressing GFP at an MOI of 0.01 or with (H) IFNa, IFNb, or Poly I:C, and cell viability was assayed 48 hr post-infection or treatment. In (I), viral titers were determined 24 hr post-infection from supernatants (n = 3; error bars indicate SEM; ***p < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA; as compared to mock-treated condition). (J and K) MRC5 (J) and GM38 (K) normal cells were pre-treated with vanadate for 4 hr and subsequently infected with VSVΔ51 or treated with IFNa, IFNb, or Poly I:C. For (D), (E), (G), (H), (J), and (K), cell viability results were normalized to the average of the values obtained for the corresponding uninfected, untreated cells (n = 4; error bars indicate SEM; NS, no statistical significance, ***p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA).

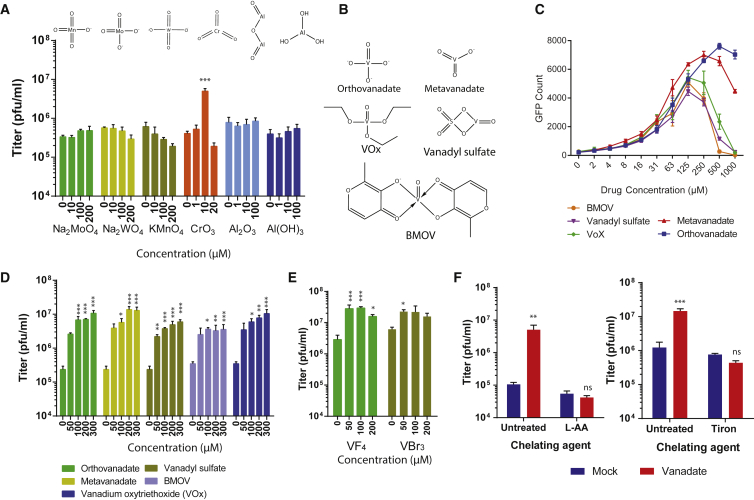

Vanadium Compounds Have Unique Viral-Enhancing Properties

Vanadate has been shown to inhibit tyrosine phosphatases, an activity which is linked to its close structural and electronic analogy to phosphate.21, 42 We therefore tested whether phosphate could induce similar effects but found various phosphate salts had no impact on viral growth in contrast to vanadate (Figure S3A). Vanadate is a simple oxometalate. We wanted to investigate whether other oxidized transition metals could potentially enhance viral growth. We found that aluminum, molybdenum, manganese, or tungsten oxides could not enhance VSVΔ51 growth (Figure 2A). Chromium trioxide modestly enhanced viral growth but only at a single dose (10 μM; Figure 2A) and was highly toxic in comparison to vanadate (data not shown). The protonation or form of vanadate at different pH had no impact on its activity (Figure S3B). Because this suggested the virus-enhancing effect was linked to the vanadium itself, we tested other oxidized vanadium complexes, including metavanadate, vanadium(V) oxytriethoxyde (VOx), vanadium(IV) oxide sulfate (VS), and bismaltolato oxovanadium(IV) (BMOV) (Figure 2B). All of these compounds effectively enhanced VSVΔ51 growth (Figures 2C, 2D, and S3C). Similar results were obtained using vanadium(IV) tetra-fluoride and vanadium(III) tri-bromide (Figure 2E). Interestingly, vanadate’s pro-viral activity was abrogated upon inclusion of L-Ascorbic Acid or tiron, both potent metal chelating agents (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Viral Enhancement Is Dependent on Vanadium

786-0 cells were pre-treated for 4 hr with indicated concentrations of (A) various oxidized transitional metals and (C–E) vanadates from various sources prepared in a pH 7.4 buffer. In (A) and (C)–(E), cells were subsequently infected with oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing GFP at an MOI of 0.01. (A, D, and E) Corresponding viral titers were determined 24 hr post-infection from supernatants (n = 3). (C) Corresponding GFP-positive cell counts 24 hr post-infection. (B) Structure of vanadium oxometalates are illustrated. (F) 786-0 were pre-treated with 200 μM of vanadate or mock and treated with chelating agent ascorbic acid (L-AA) or Tiron, then infected with VSVΔ51 (MOI, 0.01). Corresponding viral titers were determined 24 hr post-infection from supernatants (n = 3). Error bars indicate SEM. NS, no statistical significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA analysis; as compared to 0 μm or mock condition.

Vanadate Enhances Virus and Cytokine-Induced Death

Overall, our data suggested that vanadium compounds enhance the spread of a subset of RNA-based OVs in cancer cells. Next, we examined whether this extended to impact oncolytic activity. Figure 3A shows indeed that while vanadate had cytotoxic effects on its own at high doses, cancer cell death was vastly enhanced upon co-infection with a low MOI of VSVΔ51, which is otherwise innocuous to 786-0 cells. A similar effect was observed in various human cancer cell lines and with various vanadium compounds (Figure S4). The mode of cell death was found to exhibit characteristics of apoptosis as determined by flow cytometry following staining with Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we found that vanadate increased transcription of pro-apoptotic factors PUMA and Noxa that are normally induced by p53 over the course of viral infection43, 44 (Figure 3C). Interestingly, the impact of vanadate on cell death was independent of its promotion of viral spread, since increased 786-0 cell death was also observed using UV-inactivated VSV, as well as a G-less (ΔG) version of VSVΔ51 devoid of its capacity to produce glycoprotein (Figure 3D). Indeed, G-less VSVΔ51 can infect cells and replicate its genome but does not bud or spread further. All together, this suggested the potential involvement of virus-induced bystander killing, and so we tested whether antiviral IFN normally secreted following infection of 786-0 cells by VSVΔ51 could produce similar effects in combination with vanadate. Indeed, Figures 3E and 3F show that type I IFN (α and β), could lead to cytotoxicity in 786-0 cells in the presence of vanadate. Similar effects were obtained when challenging cells with Poly I:C, a toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) agonist.

The possibility that the effects of vanadate on virus-induced death could be reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated was investigated next. To evaluate this, we infected cells treated with vanadate and increasing concentrations of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), which increases cellular glutathione and reduces the levels of cellular ROS. Increasing NAC antagonized vanadate’s ability to enhance virus-induced death (Figure 3G). Similar results were observed when cells were treated with vanadate and with type I IFN (α and β) or Poly I:C (Figure 3H). However, the highest dose of NAC did not abrogate vanadate’s ability to increase viral spread (Figure 3I), again suggesting that the cytotoxic and virus-enhancing activities of vanadate are distinct. In addition, the enhancement of cell death mediated by type I IFN, Poly I:C, and VSVΔ51 by vanadate was not observed in normal adult GM38 or MRC5 human embryonic lung fibroblasts (Figures 3J and 3K).

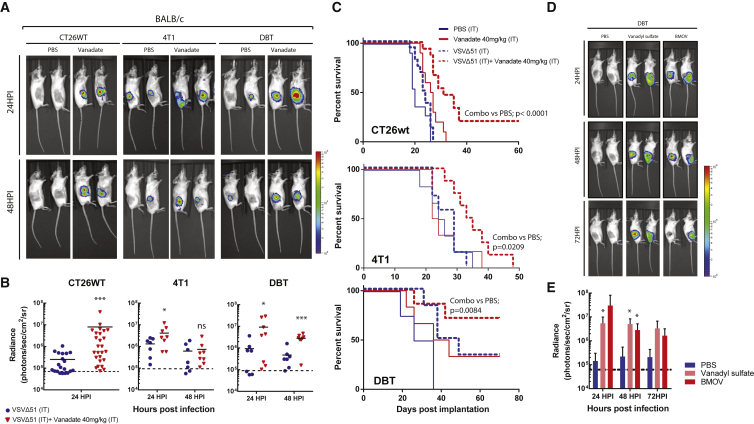

Vanadate Enhances the Oncolytic Activity of VSVΔ51 and Antitumor Immunity In Vivo

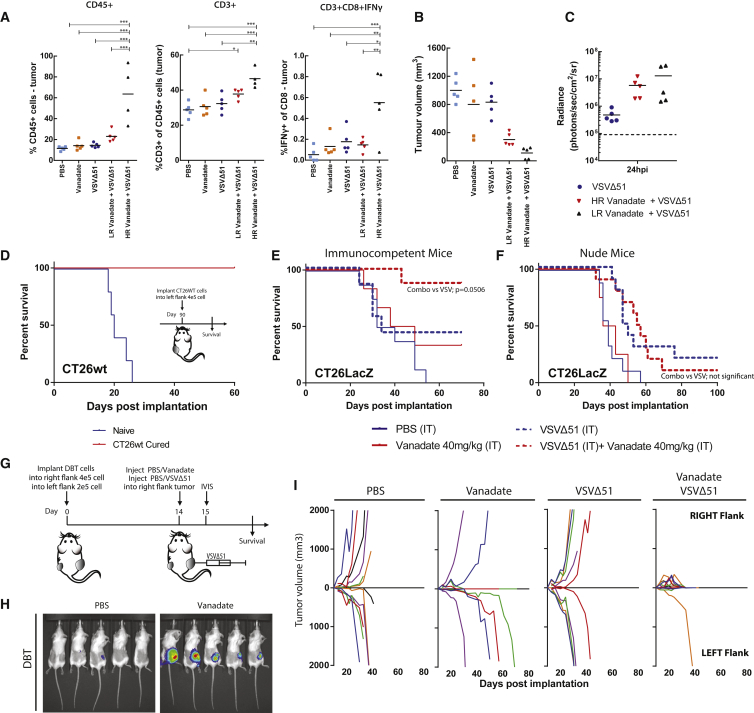

Given the observation that vanadate enhanced both spread and oncolytic activity of VSVΔ51 in vitro, we wondered if the combination of VSVΔ51 and vanadate could have anticancer effects in mouse models of cancer. Reports in the literature suggest that vanadate has immunomodulatory properties;34 hence, we performed our experiments in a panel of immunocompetent syngeneic mouse tumor models refractory to VSVΔ51 infection. In mice with established CT26WT, 4T1 (breast cancer), and DBT tumors, one single intratumoral injection of vanadate and VSVΔ51 expressing luciferase robustly enhanced virus-associated luciferase gene expression compared to virus alone, as assessed by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS; Figures 4A and 4B). Likewise, vanadyl sulfate (commonly used as a bodybuilding supplement) as well as BMOV evaluated pre-clinically for treatment of diabetes,23, 45 both robustly increased VSVΔ51 viral growth in the DBT model over the course of 3 days post-infection (Figures 4D and 4E). Vanadate and VSVΔ51 combination treatment led to significantly improved survival of DBT, CT26WT, and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice compared to the monotherapies (Figure 4C). Approximately 80% of DBT tumor-bearing mice and 20% of CT26WT tumor-bearing mice presented complete remission after combination treatment (Figure 4C). Immune profiling of CT26WT tumors indicated an enhanced leukocyte infiltration with significantly increased T cells (Figure 5A), including IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells (Figure 5A), in mice treated with the combination of vanadate and VSVΔ51 compared to the monotherapies. This suggested that induction and/or recruitment of T cells to the tumors is improved in the presence of vanadate combined with VSVΔ51, which could contribute to tumor control. Indeed, we observed a correlation between the amount of T cell infiltration and tumor regression (Figure 5B) in mice from the combined therapy group with the higher responders (HR) presenting increased infiltration compared to lower responders (LR), even though the enhancement of virus-associated luciferase gene expression was similar between them (Figure 5C). This suggests that the amount of tumor infection is not the key determinant for maximum T cell infiltration and indicates an additional need to create a milieu that promotes T cell infiltration following infection. Furthermore, mice that were able to completely eliminate CT26WT tumors (Figure 4C) subsequently became immune to rechallenge with the same cancer cells (Figure 5D), indicating that combination therapy leads to long term antitumor immunity.

Figure 4.

Vanadate Increases VSVΔ51 Efficacy in Resistant Syngeneic Tumor Models

(A–C) CT26WT, 4T1, DBT, tumor-bearing mice were treated intratumorally with the vehicle (PBS) or 40 mg/kg of vanadate (pH 7.4 prepared from orthovanadate) for 4 hr and subsequently treated with 1 × 108 PFU of oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing firefly-luciferase intratumorally. (A and B) Twenty-four and forty-eight hours post-infection, viral replication was monitored by IVIS. Representative bioluminescence images of mice are presented in (A), and quantification of luminescence is presented in (B). Scale represented in photons (n = 7–27; bars indicate mean; NS, no statistical significance; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 by one-tailed t test; as compared to mock-treated condition). (C) Survival was monitored over time. Log rank (Mantel-Cox) test indicates that the combined treatment is significantly prolonged over PBS alone (CT26WT, p < 0.0001, n = 10–16; DBT, p = 0.0084, n = 4–7; 4T1, p = 0.0209, n = 6–8). (D and E) DBT tumor-bearing mice were treated intratumorally with the vehicle (PBS), 150 mg/kg of Vanadyl sulfate, or 80 mg/kg of BMOV and subsequently with 1 × 108 PFU of oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing firefly-luciferase intratumorally. Viral replication was monitored by IVIS; representative bioluminescence images of mice are presented in (D). (E) Quantification of luminescence (n = 4–5; error bars indicate SEM; *p < 0.05 by one-tailed t test; as compared to PBS-treated condition).

Figure 5.

Vanadate/VSVΔ51 Co-treatment Triggers T Cell Infiltration and Antitumor Immunity

(A–C) CT26WT tumor-bearing mice were treated intratumorally with the vehicle (PBS) or 40 mg/kg of vanadate (pH 7.4 prepared from orthovanadate) for 4 hr and subsequently treated with 1 × 108 PFU of oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing firefly-luciferase, intratumorally. The vanadate + VSVΔ51 group was divided into two groups, High and Low responders (HR and LR), based on median tumor size 10 days post-treatment, as shown in (B). Viral replication was monitored 24 hr post-infection; quantification of luminescence is presented in (C) (n = 5). Tumor volume 10 days post-treatment is shown in (B) (n = 5). (A) Percentage of CD45+ cells; CD3+ cells of total CD45+ cells; IFNγ-expressing CD8+ cells in each tumor was quantified by flow cytometry, 10 days post-treatment (n = 4–5; error bars indicate SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001, by one-way ANOVA). (D) Survival was monitored after re-implantation of CT26WT in cured and naive mice from Figure 4C (n = 3–5). (E) Immunocompetent mice and (F) nude mice bearing the CT26LacZ tumor were treated intratumorally with the vehicle (PBS) or 40 mg/kg of vanadate for 4 hr and subsequently treated with 1 × 108 PFU of oncolytic VSVΔ51 expressing firefly-luciferase intratumorally. Log rank (Mantel-Cox) test indicates that survival in the combined treatment is significantly prolonged over VSVΔ51 alone in the immunocompetent mouse model alone (immunocompetent mice, p = 0.0506, n = 6–8; nude mice no statistical significance, n = 4–10). (G) Schematic representation of treatment schedule for bilateral DBT tumors. (H) Representative bioluminescence images of mice are presented. (I) Growth of treated (right flank) and distant (left flank) DBT tumors (n = 4–7).

Next, we investigated the effect of vanadate in the CT26LacZ tumor model, which we have previously shown to be significantly more susceptible to infection with VSVΔ51.46 Here, vanadate somewhat decreased virus-associated luminescence (Figure S5A), in line with the observation that vanadate did not enhance viral growth in cultured CT26LacZ cells (Figures S1A and S1B). However, the combination of vanadate and VSVΔ51 led to a significant improvement of survival over the monotherapies in this model, reaching nearly 90% complete remissions (Figure 5E). While enhanced bystander killing as observed in Figure 3 in part could explain this phenomenon, we wondered whether enhanced adaptive immune responses could play a role in generating such a high cure rate with a single intratumoral dose of vanadate and VSVΔ51. We therefore performed these experiments in athymic nude mice that are devoid of T cells. Remarkably, while VSVΔ51 alone still delayed tumor progression and led to cures, the combination effect was completely abrogated in this context (Figure 5F), albeit virus-associated luminescence was not generally affected (Figure S5B). Likewise, the combination therapy did not lead to enhanced efficacy in the HT29 tumors implanted in athymic nude (Figure S6C) even though enhancement of VSVΔ51 viral growth was observed (Figures S6A and S6B). These results strongly support an important role of T cell-mediated protection observed in the above-described models and the role of vanadate in eliciting an improved T cell response when combined with VSVΔ51. However, the improved efficacy of vanadate was not observed when the CT26LacZ tumors were infected with non-spreading VSVΔ51 (VSVΔ51ΔG) (Figure S5C), indicating that viral growth is essential for the combination therapy effect.

To further evaluate the role of the antitumor immune response induced by vanadate/virus treatment in tumor control, we implanted immunocompetent mice with bilateral DBT tumors and injected only the right tumors with the combination of VSVΔ51 and vanadate (or monotherapies/PBS) (Figure 5G). Interestingly, we found that while virus-associated luminescence was uniquely enhanced by vanadate in the injected tumors on the right side, the tumors on the left also shrunk following the combination therapy (Figures 5H and 5I). Although some tumors did regress following treatment with vanadate, all of the uninjected (left) tumors did not regress. VSVΔ51 monotherapy did not induce tumor regression in the injected (right) or untreated (left) tumors. Taken together, these results reveal that vanadium compounds have the ability to elicit a robust, systemic protective antitumor immune response when combined with VSVΔ51.

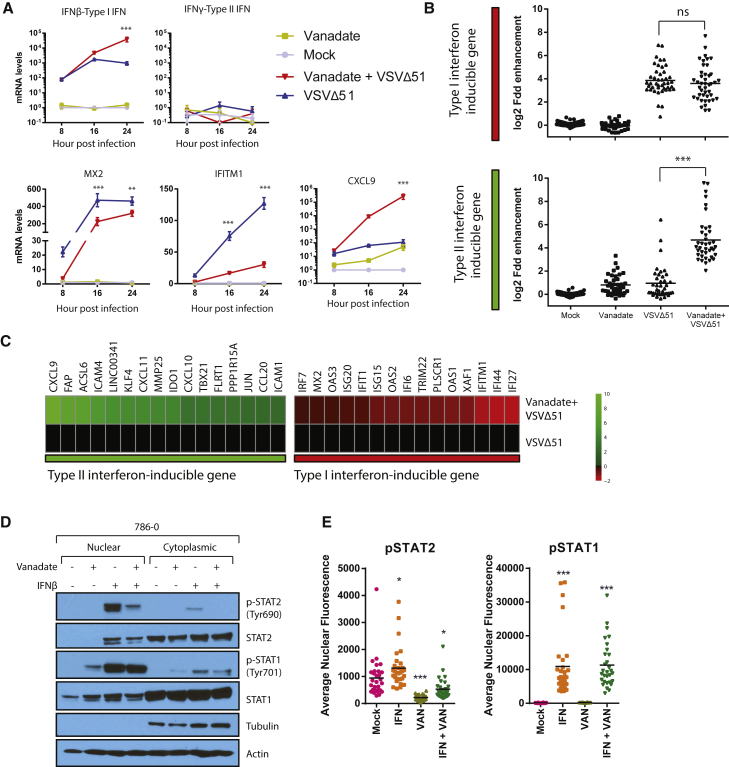

Vanadate Inhibits the Type I Interferon Response and Potentiates a Pro-inflammatory Response via Type II Interferon

Our in vitro results indicated that both OV spread and bystander killing in cancer cells can be enhanced by vanadate. While this likely contributes toward improving OV efficacy in vivo, our data suggested that a critical component of the therapeutic efficacy associated to the combination regimen in immunocompetent models involves the generation of antitumor T cell responses. To further understand the cell-autonomous molecular mechanisms involved in stimulating this response while being able to enhance infection, a microarray analysis was performed in vitro. We first looked at the gene expression profiles of 786-0 cells 24 hr following VSVΔ51 or mock infection in the presence and absence of vanadate (prepared from solutions of orthovanadate or metavanadate). In line with our demonstration that vanadate stimulates an antitumor immune response, gene set-enrichment analyses using GOrilla revealed that vanadate alone induced inflammatory responses and immune system processes, which were further potentiated in combination with VSVΔ51 (Figure S7A). Uniquely, the infection of vanadate-treated cells led to the increased expression of a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines (CCL8, CCL3, IL6, TNF, IFNβ, CCL5) and many genes typically induced by type II IFN (IFNγ), including chemokines such as CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 (Figures 6B, 6C, S7B, and S7C; Table S1). Among others, CXCL9 plays a key role in leukocyte trafficking, and its mRNA was upregulated by more than 100,000-fold during viral infection of vanadate-treated cells compared to mock (Figure 6A). We further validated the vanadate-mediated increase in mRNA expression of IFNγ-induced chemokines such as CXCL9 in mouse CT26WT cells, which were used for our in vivo models, as well as its secretion by ELISA in various human cancer cell lines (Figures S7C and S7D). While many genes typically induced by IFNγ were upregulated upon infection of vanadate-treated cells, IFNγ itself was not upregulated at any time point post-infection under any condition tested in 786-0 (Figures 6A and 6B). On the other hand, IFNβ mRNA was upregulated by more than 10-fold 24 hr following infection (Figure 6A) in vanadate-treated cells compared to virus alone. Surprisingly, genes typically induced by type I IFN were either unaffected or decreased in these conditions (Figures 6B and 6C). Indeed, genes induced by type I IFN, such as MX2 and IFITM1 with known antiviral function against rhabdoviruses were robustly downregulated as early as 8 hr post-infection (Figure 6A). Furthermore, protein expression levels of IFITM1 were potently repressed by vanadate in infected cells 16 and 24 hr following infection (Figure S8).

Figure 6.

Vanadate Re-wires Antiviral Type I IFN Signaling toward Pro-inflammatory Type II IFN Response

(A–C) Cell lysates of 786-0 treated with vanadate and VSVΔ51 expressing GFP were collected at indicated time points. RNA was extracted and probed for expression of (A) ifnβ, ifnγ, mx2, ifitm1, and cxcl9 genes by qPCR (n = 3; error bars indicate SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA; comparing the VSVΔ51 condition to the vanadate + VSVΔ51 condition). (B) RNA was used for gene expression microarray analysis. Data is normalized to untreated control, indicating log2 fold change in gene expression of genes documented to be induced by type I or type II IFN (bars indicate mean; one-way ANOVA; NS, no statistical significance, ***p < 0.0001; comparing combination treatment to virus alone condition). (C) Heatmap showing the expression levels of the differentially expressed IFN-stimulated genes. Expression of genes was normalized to values obtained for mock-treated, infected control. Color scale indicates log2 fold change. (D) 786-0 cells were pre-treated with vanadate (1,000 μM) for 4 hr and challenged with IFNβ (100 U/mL). One hour later, fractionated cell lysates were probed for pSTAT1, STAT1, pSTAT2, STAT2, and actin. (E) Immunofluorescence for pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 was performed in 786-0 cells treated with vanadate (1,000 μM) for 4 hr and with human IFNβ (1,000 U) for 1 hr. Quantification of the average nuclear fluorescence associated to pSTAT1 or pSTAT2 in each condition (n = 30; bars indicate mean; one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001; as compared to the mock condition counterpart). Microscopy images can be found in Figures S9–S11.

Importantly, IFNβ and IFNγ bind to distinct receptors and lead to differential activation of STAT1 and STAT2 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) transcription factors. Phosphorylation of STATs leads to their dimerization and nuclear translocation to activate transcription of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Some of these genes are regulated by both type I and type II IFNs, whereas others are selectively regulated by one or the other. Type I IFNs induce the phosphorylation of both STAT1 and STAT2, leading to the formation of the ISGF3 complex composed of a STAT1-STAT2 heterodimer and IRF9 that binds specific promoter regions known as IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs), while type II IFN primarily induce the phosphorylation of STAT1, leading to the formation of STAT1-STAT1 homodimers that bind IFNγ-activated-sequence (GAS) elements.47 Consistent with a shift from a type I toward a type II IFN response, vanadate treatment inhibited the IFNβ-induced phosphorylation of STAT2 and reduced its nuclear accumulation but did not similarly affect STAT1, as observed by western blot (Figure 6D). Supporting this idea, immunofluorescence also revealed that whereas activated STAT1 translocated to the nucleus following infection of vanadate-treated cells (Figures 6E and S9), STAT2 remained mostly in the cytoplasm (Figures 6E, S10, and S11). Remarkably, this suggests that vanadate enhances OV activity through a previously unappreciated mechanism that converts a predominantly antiviral type I IFN response into a type II IFN response, through the preferential repression of STAT2 activation. This signal “rewiring” leads to upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that favor the generation of a T cell-dependent antitumor response.

Discussion

OV therapy as a standalone treatment can be highly effective, but treatment resistance remains a frequent occurrence. This is attributed to a number of factors, including a need to robustly infect tumors and ensure the initiation of a robust antitumor immune response.2 The latter has prompted many investigators to evaluate OVs in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors; a strategy has been shown to be effective by several groups in both pre-clinical models and clinical trials.16, 17, 18, 48 However, this specific combination strategy is not uniformly effective.49

We show here that vanadium compounds can provide a significant therapeutic benefit in CT26WT and other various aggressive, treatment-refractory, murine tumor models when combined with OVs, leading to enhanced antitumor T cell responses mediated by the induction of a type II Interferon-like response in infected cancer cells. The availability of clinically advanced vanadium candidates such as vanadate, vanadyl sulfate, and bis(ethylmaltolato)oxovanadium(IV) (BEOV)22, 23, 50 that have been used in the context of diabetes will greatly facilitate the testing of such combination regimens in human cancer patients. In addition, oncolytic rhabdoviruses derived from VSV and closely related Maraba are currently undergoing clinical evaluation, including in combination with immune checkpoint blockade (NCT02923466, NCT02879760). All together, this lays the groundwork for rapid evaluation of our novel approach in humans. However, while many OVs including T-Vec are currently delivered intratumorally in the clinic,51 it will be relevant to further explore alternative regimens and formulations to abrogate the need for intratumoral injection of vanadium compounds ahead of virus. Oral administration of vanadium compounds is possible and has been extensively tested in the treatment of type II diabetes.52

In the present work, we tested a range of different vanadium salts and compounds. These compounds are known to undergo different hydrolytic conversions in solution.20 Orthovanadate, metavanadate, and vanadium(V) oxytriethoxide all result in a solution of H2VO4− at physiological pH, while the solutions prepared from vanadyl sulfate and vanadium(IV) fluoride will result in a solution of aqueous V(IV) and V(V),20 and those prepared from bis(maltolato)oxovanadium(IV) will contain both V(IV) and V(V) maltolato complexes.45 Importantly, all of these compounds show a robust capacity to enhance OV activity (Figures 2C–2E). This suggests significant flexibility in the design of new vanadium-based compounds that may be tailored for use in combination with OVs. Furthermore, these results are consistent with various forms of vanadate binding tightly to several phosphatases with similar Ki values.21

Protein tyrosine phosphatases are important regulators of cellular processes53, 54 and may have complex functions during the course of viral infection. Here, we found that the pan-tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor vanadate, while enhancing all of the RNA viruses in our panel (rhabdovirus, alphavirus, paramyxoviruses), substantially inhibits infection of DNA viruses like vaccinia and HSV. These observations showcase the selective effects of vanadium compounds on RNA viruses, which do not encode viral phosphatases, in contrast with both DNA viruses tested, where they serve as important virulence factors.55, 56 Notably, the RNA viruses tested generally lack the ability to counteract type I IFN signaling. When using wild-type VSV, which more effectively overcomes the type I IFN response compared to VSVΔ51, we found that the positive impact of vanadate was comparatively reduced in vitro (Figure S12). Numerous drugs and compounds have been shown to increase the efficacy of OVs by inhibition of type I IFN production or signaling.6, 7, 57, 58 The ability of vanadium compounds to convert the antiviral type I IFN to a pro-inflammatory type II IFN response, leading not only to better OV spread but also to greater antitumor immune stimulation during OV treatment is to our knowledge unprecedented.

Previously, vanadate has been reported to promote death induced by addition of type I IFN,59 supporting our observations (Figure 3). Interestingly, we found that antioxidants could abrogate the priming of apoptosis by vanadate (Figures 3G and 3H), suggesting a potential role of vanadate-induced ROS60 in promoting death initiated by type I IFN. A role for ROS in modulating IFN activity has also been previously suggested;61 however, this mechanism is unlikely to be at play here given antioxidant treatment did not abrogate enhancement of viral growth (Figure 3I). Instead, we found that STAT1 and STAT2 are differently activated by type I IFN in vanadate-treated cells, ultimately favoring the accumulation of STAT1 in the nucleus (Figures 6D, 6E, and S9–S11). This mechanism is in line with activation of type II IFN target genes that rely on STAT1-STAT1 homodimers for their transcription, even in absence of IFNγ. This could also explain the enhanced capacity for type I IFN to induce cell death (Figures 3E–3G), given STAT1 has been shown to promote cell death by interacting with TRADD, HDACs, or p53 to increase the expression of target genes such as Noxa and PUMA as observed in this study (Figure 3C).62, 63 Notably, type I IFN, such as IFNα (INTRON A) is widely used for the treatment of renal cancer, although therapeutic results remain limited.64 Further studies investigating the impact of vanadium compounds on this and other anticancer strategies that aim to kill cancer cells through type I IFN or through recruitment of T cells to the tumor site may be warranted.

Materials and Methods

Drugs, Chemicals, and Cytokines

Drugs, chemicals, and cytokines and their respective supplier and solvent used in this study are listed in Table S2. The aqueous chemistry of some of these vanadium compounds lead to conversion of the original compound into vanadate65 under the condition of the studies, and this is also indicated in Table S2.

Cell Lines

Cells and their respective supplier and growth media used in this study are listed in Table S3. Cells were cultured in HyQ high-glucose DMEM (GE Healthcare Life Sciences Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (CanSera, Etobicoke, Canada), HEPES, penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO Life Technologies, Waltham, MA). All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. All cells were tested to ensure they are free of mycoplasma contamination.

Viruses and Quantification

Rhabodviruses

The Indiana serotype of VSV (VSVΔ51 or wild-type) was used throughout this study and was propagated in Vero cells. VSVΔ51 expressing GFP or firefly luciferase are recombinant derivatives of VSVΔ51 described previously.38 All viruses were propagated on Vero cells and purified on 5%–50% Optiprep (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) gradient, and all virus titers were quantified by the standard plaque assay on Vero cells as previously described.66

Herpes Simplex Virus

The HSV-1 N212 expressing GFP67 was a gift from Dr. Karen Mossman (McMaster University, Canada). HSV virus titers were quantified by the standard plaque assay on Vero cells as previously described.67

Measles Virus

The measles virus (MV) expressing GFP (Schwartz strain) was a gift from Dr. Guy Ungerechts (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Canada). MV virus titers were quantified on Vero cells.

Sindbis Virus

The sindbis virus expressing GFP was a gift from Dr. Benjamin tenOever (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY, USA). The Sindbis virus was quantified by the standard plaque assay in Vero cells. Plaques were counted 3 days post-infection.

Vaccinia Virus

Vaccinia virus (Wyeth strain deleted for thymidine kinase and expressing GM-CSF) was quantified by plaque assay in U20S cells as described previously.68

Cell Viability Assay

The metabolic activity of the cells was assessed using alamarBlue (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Treated and/or infected cells in a 96-well plate (Corning, Manassas, VA) were treated, at indicated time, with 10 μL of alamarBlue in each well and incubated for 2 to 4 hr. Fluorescence was measured at 590 nm upon excitation at 530 nm using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Labsystems, Beverly, MA).

Microarray and Analysis

The 786-0 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 in 6-well dishes and allowed to adhere overnight. The next day, cells were pre-treated for 4 hr with orthovanadate (150 μM), metavanadadate (150 μM), or the vehicle. Following pre-treatment, the cells were infected with VSVΔ51 at an MOI of 0.01 or left uninfected. Twenty-four hours post-infection, RNA was collected using an RNA-easy kit (QIAGEN, Toronto, Canada). Biological triplicates were subsequently pooled, and RNA quality was measured using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, Canada) before hybridization. Hybridization to Affymetrix Human PrimeView Array was performed by The Centre for Applied Genomics, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. Microarray data was processed using Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) 3.0 under default parameters of Gene Level Differential Expression Analysis. Fold change in gene expression was calculated for each gene in relation to uninfected, untreated control. Heatmap of normalized expression values was generated using R package pheatmap. Volcano plots of gene expression values were generated using R. Gene ontology enrichments analysis was evaluated using GOrilla69 following correction for multiple hypothesis testing (Benjamini-Hochberg). Raw and processed microarray data have been deposited in the NCBI-Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO: GSE97327).

Mouse Tumor Models

CT26WT, CT26LacZ, DBT, 4T1 Models

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Senneville, Canada) were given subcutaneous tumors by injecting 3 × 105 syngeneic CT26WT, CT26-LacZ, or DBT cells, or 2 × 105 4T1 cells, suspended in 100 μL PBS. Ten days (4T1), 11 days (CT26WT, CT26LacZ), or 13 days (DBT) post-implantation, tumors were treated intratumorally once with a chemical compound (dissolved in PBS) or the vehicle as indicated. Four hours later, tumors were injected intratumorally with 1 × 108 plaque-forming units (PFU) (in 25 μL PBS) of the indicated virus. Tumor sizes were measured every other day using an electronic caliper. Numerical ear tagging system enabled unbiased data collection. Tumor volume was calculated as = (length2 × width)/2. For survival studies, mice were culled when tumors had reached 1,500 mm3. For in vivo imaging, an IVIS (Perkin Elmer) was used as described previously.8 Quantification of the bioluminescent signal intensities in each mouse was measured using Living Image v2.50.1 software. Mice were randomized to the different treatment groups according to tumor size in all experiments. Mice with no palpable tumors on initial treatment day were excluded from study. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

HT29 Model

Six-week-old CD1 nude mice were given subcutaneous tumors by injecting 1 × 106 syngeneic HT29 cells suspended in 100 μL serum-free DMEM. When tumors grew to approximately 5 mm × 5 mm (between 18 and 25 days post-implantation), mice were treated intratumorally once with a chemical compound (dissolved in PBS) or the vehicle as indicated. Four hours later, tumors were injected intratumorally with 1 × 108 PFU of the indicated virus. Tumor dimensions were measured every other day with electronic calipers.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the University of Ottawa Animal Care and Veterinary Services guidelines for animal care under the protocol OHRI-2265 and OHRI-2264.

Ex Vivo Tumor Model

BALB/c mice were implanted with subcutaneous CT26WT or DBT cells. Mice were sacrificed after tumors had reached at least 10 mm × 10 mm in size. Tumor, lung, spleen, and brain tissue were extracted from the mice, cut into 2-mm thick slices, and cored into 2 mm × 2 mm pieces using a punch biopsy. Each tissue core was incubated in 1 mL of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 30 mM HEPES, and were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cores were treated for 4 hr with indicated concentration of chemical compound. Subsequently, the cores were then infected VSVΔ51-GFP. GFP pictures were taken for each core 24 hr post-infection.

Flow Cytometry

Cell Death Staining

The 786-0 cells were plated in 6-well dishes and treated as indicated. Twenty-four hours post-infection, cells were collected and stained with Annexin V and 7-AAD according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using the APC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with 7-AAD (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Collected samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD LSRFortessa (data analyzed with the FlowJo software).

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Ten days post-treatment, BALB/c tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were collected and dissociated using the Tumor Dissociation Kit-Mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer. Upon resuspension in R10 buffer (RPMI, 10% FBS), the cells were counted, and 1.5e6 cells per condition were stained. Cells were then stained with the FVS780 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) viability for 15 min at room temperature. After washes, cells were incubated with anti-CD16/32 in 0.5% BSA/PBS at 4°C to block nonspecific antibody (Ab) interaction with Fc receptors. For surface staining, cells were incubated with combinations of anti-CD45-BV786, anti-CD3-AF700, and anti-CD8 PE-CF594 (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed twice and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) buffer for analysis. For intracellular staining, cells were incubated in the presence of golgiplug for 5 hr and stained with anti-IFNγ-PE according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD Biosciences). Collected samples were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD LSRFortessa and data analyzed with the FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Immunoblotting

Cells were pelleted and lysed on ice for 30 minutes using 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 100 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and 1% Triton X-100. For nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts, the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used according to the provided protocol. Following protein determination by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Protein Assay Solution), 20 μg of clarified cell lysates were electrophoresed on NuPAGE Novex 4%–12% Bis-Tris precast Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the XCell SureLock Mini-Cell System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred on nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C, Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked with 5% BSA or milk and probed with antibodies specific for phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701, #9171, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:1,000) and Stat1 (#9172, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:1,000), Stat2 (#72604, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:1,000), phospho-Stat2 (#88410S, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:1,000), IFITM1 (#60074-1-Ig, Proteintech Group, used at 1:1,000), VSV (a gift from Dr Earl Brown, used at 1:2,000), or β-actin (#4970, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:1,000). Blots were then probed with a goat anti-rabbit or mouse peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Labs, West Grove, PA). Bands were visualized using the Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All uncropped western blots are available in Figure S13.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured on coverslips prior to treatment with vanadate and human IFNβ subsequently. Following 1 hr incubation with IFNβ, the cells were washed with cold PBS and fixed using ice-cold methanol:acetone (1:1). Blocking buffer (5% FBS, 0.3% triton, PBS) and Ab dilution buffer were used (1% BSA, 0.3% triton, PBS). The cells were stained using a rabbit anti-phospho-Stat1 (Tyr701, #9171, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:500), Stat2 (#72604, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:200), or phospho-Stat2 (#88410S, Cell Signaling Technology, used at 1:200) and subsequently with a goat anti-rabbit-488 secondary Ab (#A-11008, Life Technologies). Prolong gold anti-fade with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes) was used to mount the coverslips onto slides. The images were captured using the EVOS microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantification for nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio or the average nuclear fluorescence was performed on ImageJ.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

786-0 or CT26WT cells were pre-treated for 4 hr with chemical compound or the vehicle and were infected with VSVΔ51 at MOI 0.01 or left uninfected. Twenty-four hours post-infection, cells were collected and RNA extraction was performed using the QIAGEN RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). RNA quantity and purity was assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) RNA was converted to cDNA with RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR reactions were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN) on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene expression was relative to GAPDH or β-actin. Fold induction was calculated relative to the untreated/uninfected samples for each gene. List of qPCR primers used in this study are listed in Table S4.

ELISA

786-0 cells plated in 12-well dishes were pre-treated with drug or the vehicle for 4 hr and subsequently infected with VSVΔ51-GFP at indicated MOI or left uninfected. Cell supernatants were collected at different times post-infection as indicated. IFNα and IFNβ quantification was performed using the Verikine Human IFNα or IFNβ ELISA kit (PBL Assay Science, Piscataway, NJ) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance values at 450 nM were measured on a Multiskan Ascent Microplate Reader (MXT Lab Systems).

Cytokine Array

Supernatants from treated 786-0 cells were assayed screened with the RayBio Cytokine Antibody Arrays - Human Cytokine Antibody Array System 3 (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed using ImageJ and Analysis Tool for AAH-CYT-3 (RayBiotech).

Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t test or one-way or two way ANOVA test as indicated in the figure legends. The log rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to determine significant differences in plots for survival studies. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 and Excel.

Author Contributions

M.S., C.R., A.B., H.H.S., N.A.E.-S., and O.V. conducted in vitro experiments. M.S., A.C., F.T., A.B., and R.K. performed mouse experiments. F.T. performed the flow cytometry acquisition and analysis. F.L.B. provided material. J.-S.D. and M.S. participated in the conception and design of the study. M.S. and J.-S.D. drafted the manuscript with editorial contributions from D.C.C., J.C.B., F.T., and R.K. J.-S.D., D.C.C., and J.C.B. supervised the study.

Acknowledgments

J.-S.D. is supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award - Infection and Immunity (INI-147824). J.-S.D. and J.C.B. hold grants from the Terry Fox Research Institute (TFF 122868) and the Canadian Cancer Society, generously supported by the Lotte & John Hecht Memorial Foundation (703014). M.S. is supported by a CIHR doctoral fellowship. O.V., H.H.S. are supported by a CIHR master’s award. R.K. was supported by a Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science & Technology. A.B. was supported by a BioCanRx summer studentship award. We would also like to thank Dr. Rozanne Arulanandam for reviewing the manuscript and Dr. Guy Ungerechts (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute) and Dr. Karen Mossman (McMaster University) for generously providing MV and HSV viruses, respectively.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes thirteen figures and four tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.10.014.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Ilkow C.S., Swift S.L., Bell J.C., Diallo J.-S. From scourge to cure: tumour-selective viral pathogenesis as a new strategy against cancer. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003836. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell S.J., Peng K.-W., Bell J.C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:658–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawler S.E., Chiocca E.A. Oncolytic virus-mediated immunotherapy: a combinatorial approach for cancer treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2812–2814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andtbacka R.H.I., Kaufman H.L., Collichio F., Amatruda T., Senzer N., Chesney J., Delman K.A., Spitler L.E., Puzanov I., Agarwala S.S. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Boeuf F., Selman M., Son H.H., Bergeron A., Chen A., Tsang J., Butterwick D., Arulanandam R., Forbes N.E., Tzelepis F. Oncolytic maraba virus MG1 as a treatment for sarcoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141:1257–1264. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escobar-Zarate D., Liu Y.-P., Suksanpaisan L., Russell S.J., Peng K.-W. Overcoming cancer cell resistance to VSV oncolysis with JAK1/2 inhibitors. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:582–589. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arulanandam R., Batenchuk C., Varette O., Zakaria C., Garcia V., Forbes N.E., Davis C., Krishnan R., Karmacharya R., Cox J. Microtubule disruption synergizes with oncolytic virotherapy by inhibiting interferon translation and potentiating bystander killing. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dornan M.H., Krishnan R., Macklin A.M., Selman M., El Sayes N., Son H.H., Davis C., Chen A., Keillor K., Le P.J. First-in-class small molecule potentiators of cancer virotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26786. doi: 10.1038/srep26786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felt S.A., Droby G.N., Grdzelishvili V.Z. Ruxolitinib and polycation combination treatment overcomes multiple mechanisms of resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00461-17. e00461-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamarin D., Holmgaard R.B., Subudhi S.K., Park J.S., Mansour M., Palese P., Merghoub T., Wolchok J.D., Allison J.P. Localized oncolytic virotherapy overcomes systemic tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:226ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichty B.D., Breitbach C.J., Stojdl D.F., Bell J.C. Going viral with cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:559–567. doi: 10.1038/nrc3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilkow C.S., Marguerie M., Batenchuk C., Mayer J., Ben Neriah D., Cousineau S., Falls T., Jennings V.A., Boileau M., Bellamy D. Reciprocal cellular cross-talk within the tumor microenvironment promotes oncolytic virus activity. Nat. Med. 2015;21:530–536. doi: 10.1038/nm.3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalkavan H., Sharma P., Kasper S., Helfrich I., Pandyra A.A., Gassa A., Virchow I., Flatz L., Brandenburg T., Namineni S. Spatiotemporally restricted arenavirus replication induces immune surveillance and type I interferon-dependent tumour regression. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14447. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourgeois-Daigneault M.-C., Roy D.G., Falls T., Twumasi-Boateng K., St-Germain L.E., Marguerie M., Garcia V., Selman M., Jennings V.A., Pettigrew J. Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus expressing interferon-σ has enhanced therapeutic activity. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2016;3:16001. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamarin D., Holmgaard R.B., Ricca J., Plitt T., Palese P., Sharma P., Merghoub T., Wolchok J.D., Allison J.P. Intratumoral modulation of the inducible co-stimulator ICOS by recombinant oncolytic virus promotes systemic anti-tumour immunity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14340. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z., Ravindranathan R., Kalinski P., Guo Z.S., Bartlett D.L. Rational combination of oncolytic vaccinia virus and PD-L1 blockade works synergistically to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14754. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen W., Patnaik M.M., Ruiz A., Russell S.J., Peng K.-W. Immunovirotherapy with vesicular stomatitis virus and PD-L1 blockade enhances therapeutic outcome in murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:1449–1458. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-652503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribas A., Dummer R., Puzanov I., VanderWalde A., Andtbacka R.H.I., Michielin O., Olszanski A.J., Malvehy J., Cebon J., Fernandez E. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–1119.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saha D., Martuza R.L., Rabkin S.D. Macrophage polarization contributes to glioblastoma eradication by combination immunovirotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:253–267.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crans D.C., Smee J.J., Gaidamauskas E., Yang L. The chemistry and biochemistry of vanadium and the biological activities exerted by vanadium compounds. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:849–902. doi: 10.1021/cr020607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLauchlan C.C., Peters B.J., Willsky G.R., Crans D. Vanadium–phosphatase complexes: Phosphatase inhibitors favor the trigonal bipyramidal transition state geometries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015;301–302:163–199. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson K.H., Lichter J., LeBel C., Scaife M.C., McNeill J.H., Orvig C. Vanadium treatment of type 2 diabetes: a view to the future. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009;103:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson K.H., Orvig C. Vanadium in diabetes: 100 years from phase 0 to phase I. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:1925–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evangelou A.M. Vanadium in cancer treatment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2002;42:249–265. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishayee A., Waghray A., Patel M.A., Chatterjee M. Vanadium in the detection, prevention and treatment of cancer: the in vivo evidence. Cancer Lett. 2010;294:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa Pessoa J. Thirty years through vanadium chemistry. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015;147:4–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozzo C., Sanna D., Garribba E., Serra M., Cantara A., Palmieri G., Pisano M. Antitumoral effect of vanadium compounds in malignant melanoma cell lines. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017;174:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu J.-X., Hong Y.-H., Yang X.-G. Bis(acetylacetonato)-oxidovanadium(IV) and sodium metavanadate inhibit cell proliferation via ROS-induced sustained MAPK/ERK activation but with elevated AKT activity in human pancreatic cancer AsPC-1 cells. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2016;21:919–929. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark O., Park I., Di Florio A., Cichon A.-C., Rustin S., Jugov R., Maeshima R., Stoker A.W. Oxovanadium-based inhibitors can drive redox-sensitive cytotoxicity in neuroblastoma cells and synergise strongly with buthionine sulfoximine. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naso L.G., Badiola I., Marquez Clavijo J., Valcarcel M., Salado C., Ferrer E.G., Williams P.A.M. Inhibition of the metastatic progression of breast and colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo in murine model by the oxidovanadium(IV) complex with luteolin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016;24:6004–6011. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petanidis S., Kioseoglou E., Domvri K., Zarogoulidis P., Carthy J.M., Anestakis D., Moustakas A., Salifoglou A. In vitro and ex vivo vanadium antitumor activity in (TGF-β)-induced EMT. Synergistic activity with carboplatin and correlation with tumor metastasis in cancer patients. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;74:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustelin T., Vang T., Bottini N. Protein tyrosine phosphatases and the immune response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:43–57. doi: 10.1038/nri1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Shea J.J., McVicar D.W., Bailey T.L., Burns C., Smyth M.J. Activation of human peripheral blood T lymphocytes by pharmacological induction of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10306–10310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsave O., Petanidis S., Kioseoglou E., Yavropoulou M.P., Yovos J.G., Anestakis D., Tsepa A., Salifoglou A. Role of vanadium in cellular and molecular immunology: association with immune-related inflammation and pharmacotoxicology mechanisms. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016;2016:4013639. doi: 10.1155/2016/4013639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ustarroz-Cano M., Garcia-Pelaez I., Cervantes-Yepez S., Lopez-Valdez N., Fortoul T.I. Thymic cytoarchitecture changes in mice exposed to vanadium. J. Immunotoxicol. 2017;14:9–14. doi: 10.1080/1547691X.2016.1250848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon Y.J., Romanowski E., Berman J., Vikoren P., Lin L.S., Schlessinger D., Araullo-Cruz T. Vanadate promotes reactivation and iontophoresis-induced ocular shedding of latent HSV-1 W in different host animals. Curr. Eye Res. 1990;9:1015–1021. doi: 10.3109/02713689009069938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto F., Fujioka H., Iinuma M., Takano M., Maeno K., Nagai Y., Ito Y. Enhancement of Newcastle disease virus-induced fusion of mouse L cells by sodium vanadate. Microbiol. Immunol. 1984;28:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1984.tb02948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stojdl D.F., Lichty B.D., tenOever B.R., Paterson J.M., Power A.T., Knowles S., Marius R., Reynard J., Poliquin L., Atkins H. VSV strains with defects in their ability to shutdown innate immunity are potent systemic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veinalde R., Grossardt C., Hartmann L., Bourgeois-Daigneault M.-C., Bell J.C., Jäger D., von Kalle C., Ungerechts G., Engeland C.E. Oncolytic measles virus encoding interleukin-12 mediates potent anti-tumor effects through T cell activation. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1285992. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1285992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mossman K.L., Macgregor P.F., Rozmus J.J., Goryachev A.B., Edwards A.M., Smiley J.R. Herpes simplex virus triggers and then disarms a host antiviral response. J. Virol. 2001;75:750–758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.750-758.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parato K.A., Breitbach C.J., Le Boeuf F., Wang J., Storbeck C., Ilkow C., Diallo J.S., Falls T., Burns J., Garcia V. The oncolytic poxvirus JX-594 selectively replicates in and destroys cancer cells driven by genetic pathways commonly activated in cancers. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:749–758. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gresser M.J., Tracey A.S., Stankiewicz P.J. The interaction of vanadate with tyrosine kinases and phosphatases. Adv. Protein Phosphatases. 1987;4:35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lallemand C., Blanchard B., Palmieri M., Lebon P., May E., Tovey M.G. Single-stranded RNA viruses inactivate the transcriptional activity of p53 but induce NOXA-dependent apoptosis via post-translational modifications of IRF-1, IRF-3 and CREB. Oncogene. 2007;26:328–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takaoka A., Hayakawa S., Yanai H., Stoiber D., Negishi H., Kikuchi H., Sasaki S., Imai K., Shibue T., Honda K., Taniguchi T. Integration of interferon-alpha/beta signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence. Nature. 2003;424:516–523. doi: 10.1038/nature01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orvig C., Caravan P., Gelmini L., Glover N., Herring F.G., Li H., McNeil J.H., Rettig S.J., Setyawati I.A. Reaction chemistry of BMOV, bis(maltolato)oxovanadium(IV), a potent insulin mimetic agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:12759–12770. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruotsalainen J.J., Kaikkonen M.U., Niittykoski M., Martikainen M.W., Lemay C.G., Cox J., De Silva N.S., Kus A., Falls T.J., Diallo J.S. Clonal variation in interferon response determines the outcome of oncolytic virotherapy in mouse CT26 colon carcinoma model. Gene Ther. 2015;22:65–75. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Platanias L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puzanov I., Milhem M.M., Minor D., Hamid O., Li A., Chen L., Chastain M., Gorski K.S., Anderson A., Chou J. Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2619–2626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shim K.G., Zaidi S., Thompson J., Kottke T., Evgin L., Rajani K.R., Schuelke M., Driscoll C.B., Huff A., Pulido J.S., Vile R.G. Inhibitory receptors induced by VSV viroimmunotherapy are not necessarily targets for improving treatment efficacy. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:962–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crans D.C. Antidiabetic, chemical, and physical properties of organic vanadates as presumed transition-state inhibitors for phosphatases. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:11899–11915. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bommareddy P.K., Patel A., Hossain S., Kaufman H.L. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) and other oncolytic viruses for the treatment of melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017;18:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith D.M., Pickering R.M., Lewith G.T. A systematic review of vanadium oral supplements for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. QJM. 2008;101:351–358. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li S., Zhu M., Pan R., Fang T., Cao Y.-Y., Chen S., Zhao X., Lei C.Q., Guo L., Chen Y. The tumor suppressor PTEN has a critical role in antiviral innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:241–249. doi: 10.1038/ni.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tonks N.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–846. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J.-Y., Yeh C.-L., Chou H.-C., Yang C.-H., Fu Y.-N., Chen Y.-T., Cheng H.W., Huang C.Y., Liu H.P., Huang S.F., Chen Y.R. Vaccinia H1-related phosphatase is a phosphatase of ErbB receptors and is down-regulated in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10177–10184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He B., Gross M., Roizman B. The gamma(1)34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1alpha to dephosphorylate the alpha subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:843–848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyên T.L.-A., Abdelbary H., Arguello M., Breitbach C., Leveille S., Diallo J.-S., Yasmeen A., Bismar T.A., Kirn D., Falls T. Chemical targeting of the innate antiviral response by histone deacetylase inhibitors renders refractory cancers sensitive to viral oncolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14981–14986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803988105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alain T., Lun X., Martineau Y., Sean P., Pulendran B., Petroulakis E., Zemp F.J., Lemay C.G., Roy D., Bell J.C. Vesicular stomatitis virus oncolysis is potentiated by impairing mTORC1-dependent type I IFN production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:1576–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912344107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gamero A.M., Larner A.C. Vanadate facilitates interferon alpha-mediated apoptosis that is dependent on the Jak/Stat pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13547–13553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang C., Zhang Z., Ding M., Li J., Ye J., Leonard S.S., Shen H.M., Butterworth L., Lu Y., Costa M. Vanadate induces p53 transactivation through hydrogen peroxide and causes apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32516–32522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon A.R., Rai U., Fanburg B.L., Cochran B.H. Activation of the JAK-STAT pathway by reactive oxygen species. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C1640–C1652. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim H.S., Lee M.-S. STAT1 as a key modulator of cell death. Cell. Signal. 2007;19:454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Townsend P.A., Scarabelli T.M., Davidson S.M., Knight R.A., Latchman D.S., Stephanou A. STAT-1 interacts with p53 to enhance DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5811–5820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bukowski R.M. Immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma. Oncology. 1999;13:801–810. discussion 810, 813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levina A., Crans D.C., Lay P.A. Speciation of metal drugs, supplements and toxins in media and bodily fluids controls in vitro activities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017 Published online January 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diallo J.-S., Vähä-Koskela M., Le Boeuf F., Bell J. Propagation, purification, and in vivo testing of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus strains. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;797:127–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-340-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sobol P.T., Boudreau J.E., Stephenson K., Wan Y., Lichty B.D., Mossman K.L. Adaptive antiviral immunity is a determinant of the therapeutic success of oncolytic virotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:335–344. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breitbach C.J., Burke J., Jonker D., Stephenson J., Haas A.R., Chow L.Q.M., Nieva J., Hwang T.H., Moon A., Patt R. Intravenous delivery of a multi-mechanistic cancer-targeted oncolytic poxvirus in humans. Nature. 2011;477:99–102. doi: 10.1038/nature10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eden E., Navon R., Steinfeld I., Lipson D., Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.