Abstract

Background

Anti-microbial peptides (AMPs), naturally encoded by genes and generally containing 12–100 amino acids, are crucial components of the innate immune system and can protect the host from various pathogenic bacteria and viruses. In recent years, the widespread use of antibiotics has resulted in the rapid growth of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms that often induce critical infection and pathogenesis. Recently, the advent of high-throughput technologies has led molecular biology into a data surge in both the amount and scope of data. For instance, next-generation sequencing technology has been applied to generate large-scale sequencing reads from foods, water, soil, air, and specimens to identify microbiota and their functions based on metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, respectively. In addition, oolong tea is partially fermented and is the most widely produced tea in Taiwan. Many studies have shown the benefits of oolong tea in inhibiting obesity, reducing dental plaque deposition, antagonizing allergic immune responses, and alleviating the effects of aging. However, the microbes and their functions present in oolong tea remain unknown.

Results

To understand the relationship between Taiwanese oolong teas and bacterial communities, we designed a novel bioinformatics scheme to identify AMPs and their functional types based on metagenomics and metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data. Four types of oolong teas (Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, Jinxuan tea, and Oriental Beauty tea) were subjected to 16S ribosomal DNA and total RNA extraction and sequencing. Metagenomics analysis results revealed that Oriental Beauty tea exhibited greater bacterial diversity than other teas. The most common bacterial families across all tea types were Bacteroidaceae (21.7%), Veillonellaceae (22%), and Fusobacteriaceae (12.3%). Metatranscriptomics analysis results revealed that the dominant bacteria species across all tea types were Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Chryseobacterium sp. StRB126, which were subjected to further functional analysis. A total of 8194 (6.5%), 26,220 (6.1%), 5703 (5.8%), and 106,183 (7.8%) reads could be mapped to AMPs.

Conclusion

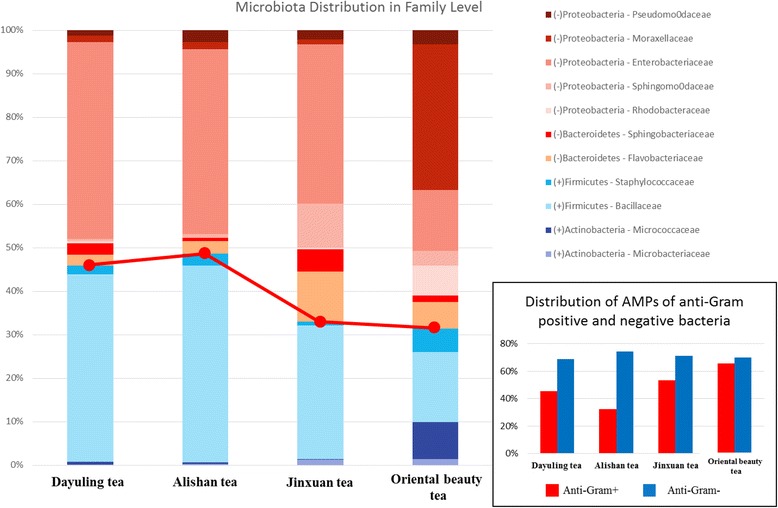

We found that the distribution of anti-gram-positive and anti-gram-negative AMPs is highly correlated with the distribution of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in Taiwanese oolong tea samples.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12918-017-0503-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, Amp, Next-generation sequencing, Metagenomics, Metatranscriptomics, Oolong teas

Background

Anti-microbial peptides (AMPs), naturally encoded by genes and generally consisting of 12–100 amino acids, are crucial components of the innate immune system and can protect the host from various pathogenic bacteria and viruses [1]. In recent years, the widespread use of antibiotics has resulted in the rapid growth of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms that often induce critical infection and pathogenesis. Because of their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities, AMPs are active against a variety of pathogens, such as gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial, fungi, viruses, and parasites [2]. Thus, it is important to identify natural AMPs for the development of new antibiotics. Many approaches have been proposed for the development of potential drugs, such as in silico prediction of AMPs based on protein sequences. Currently, more than 3900 natural AMPs have been identified in plants and animals [3]. In a previous study, Wan et al. [4] found that green tea possessed high antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli by inducing the secretion of plant antimicrobial peptides.

Teas can be classified according to their degree of fermentation: non-fermented green tea, partially fermented oolong tea, completely fermented black tea, and post-fermented dark tea [5]. Oolong tea is the highest yielding tea in Taiwan, accounting for over 90% of total tea production annually. Previous studies have reported that oolong tea can inhibit obesity [6], reduce dental plaque deposition [7], antagonize allergies [8], and moderate aging [9]. Investigations of microbes in Puer tea have been reported previously by Wen et al. [10], Zhou et al. [11], and Xu et al. [12], who showed that Candida and Aspergillus niger were the dominant microbes in Puer tea. However, the microbes present in oolong teas have not been identified and it is unknown which AMPs are produced by bacteria in oolong tea.

Recently, the advent of high-throughput technologies has led molecular biology into a data surge in both the growth and scope of data. For instance, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been applied to generate large-scale sequencing reads from foods, water, soil, air, and specimens to identify microbiota and their functions based on metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, respectively. Additionally, mass spectrometry is widely applied in proteomics studies to detect thousands of peptides in one experiment.

The emergence of NGS technology has enabled analysis of genetic materials obtained directly from the environment and examination of biological diversity in a sensitive and efficient manner that it not possible using traditional approaches. While metagenomics studies target species diversity at the DNA level, metatranscriptomics analyses are used to investigate the activities and interactions among microbial communities in the extracted environment based on expression profiles [13]. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics analyses of diverse microscopic organisms in their natural environments, including the human body, have revolutionized the understanding of the relationships between microbes and their hosts. Compared with functional gene microarrays, metatranscriptomic sequencing can detect gene transcripts without the restriction of targeting a specific species in complicated biological systems. Furthermore, without the noise associated with hybridization signals, discrete output of metatranscriptomic sequencing enables analysis of fine-scale variations in transcript sequences [14]. Metatranscriptomic sequencing has been applied to different levels. For example, Jung et al. [15] profiled the metatranscriptome of microbial species active during kimchi fermentation. Marchetti et al. [16] and Mason et al. [17] sequenced the transcriptomes of ocean microbes to identify active members their functional responses after environmental changes. Maurice et al. [18] conducted metatranscriptome profiling, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and flow cytometry to identify dominant bacterial species in the human gut microbiota as well as the physiology and gene expression responses of bacteria to xenobiotics. John et al. [14] showed that Illumina sequencing could detect more significant differential genes than microarray; after qPCR validation, the difference in gene expression from sequencing data was found to be more consistent with those of real biological situations. Thus, RNA-seq analysis is less restricted than microarray and provides more gene expression information.

The relationship between microbial species and humans has been reported previously. For example, Arumugam et al. [19] revealed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were major groups of human intestinal microbiota, Ley et al. [20] showed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were human gut microbes associated with obesity, Kostic et al. [21] found that the number of Fusobacteria in colon cancer cells was higher than in healthy colon tissues, and Scheperjans et al. [22] showed that the number of bacteria from Prevotellaceae in patients with Parkinson’s disease was much lower than in the normal gut. In contrast, the microbes present in oolong tea and their functions remain unknown.

Rapidly advancing technologies have enabled examination of the genome, transcriptome, and proteome in a comprehensive manner. However, extracting meaningful information from large amounts of data and evaluating biological functions from a systems biology perspective are very challenging in bioinformatics studies. Therefore, to understand the distribution of microbiota and their potential functions in oolong teas, we conducted metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing of four different Taiwanese oolong teas: Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, Jinxuan tea, and Oriental Beauty tea. Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, Jinxuan tea, and Oriental Beauty tea differ in their regions of origin and production processes. Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, and Jinxuan tea are lightly fermented high-mountain teas produced with varying degrees of roasting: non-roasted, medium roast, and light roast, respectively. In contrast, Oriental Beauty tea is a heavily fermented, light-roast tea and is made from tea leaves infested with Jacobiasca formosana [23]; thus, this tea may contain commensal microbial communities that differ from those in Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, and Jinxuan tea.

The aims of this study were to identify the dominant microbial species and their potential functions and identify AMPs and their functional types in different oolong teas. We developed a novel bioinformatics method for identifying AMPs and their functional types based on metagenomics and metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data. This is the first study to analyze microbial diversity in Taiwanese oolong teas using metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches.

Methods

DNA and RNA extraction

Three grams of green tea leaves were mixed with 150 mL of tap water and DNA and RNA were extracted from the mixture. The QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used for DNA extraction. Each sample was transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min to pellet the bacteria. Bacterial pellets were suspended in 180 mL of an appropriate enzyme solution and incubated for at least 30 min at 37 °C. Next, 20 mL proteinase K and 200 mL Buffer AL were added to the sample and mixed by vortexing. Each suspension was incubated at 56 °C for 30 min and then for an additional 15 min at 95 °C. The sample was briefly centrifuged to pellet the suspension. After this, extraction was conducted following the protocol of the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit. DNA was eluted with 30 mL Buffer AE and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min. The DNA extract was stored at 220 °C until further analysis.

For RNA extraction, 0.5 mL of 100% isopropanol was added to the aqueous phase and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min. This sample was centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was removed from the tube, leaving only the RNA pellet. The RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL of 75% ethanol and then vortexed to mix. Following centrifugation at 7500×g for 5 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was discarded and the RNA pellet was air-dried for 10 min. The RNA pellet was resuspended in 20 μL diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water by passing the solution up and down several times through a pipette tip and then incubated in a water bath or heat block at 55 °C for 10 min. The sample was stored at −80 °C.

Library preparation and sequencing

Two PCR primers, F515 (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-TAA-3′) and R806 (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), were used to target the V4 domain of bacterial 16S rRNA. PCR amplification was performed in a 50-mL reaction volume containing 25 mL 2× Phusion Flash Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.5 mM of each forward and reverse primer, and 50 ng DNA template. The reaction conditions consisted of an initial 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplified products were evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Amplicons were purified using the AMPure XP PCR Purification Kit (Agencourt, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher) on a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For V4 library preparation, Illumina adapters were attached to the amplicons using the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation v2 Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Purified libraries were applied for cluster generation and sequencing on the MiSeq system.

Total RNA (150 ng) was used for RNA-seq library construction with the Bacteria ScriptSeq complete kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, ribosomal RNA was removed from total RNA. Next, cDNA synthesis, 5′ tagging, 3′ tagging, and index PCR were sequentially conducted to construct the index library for the Illumina sequencing platform. Libraries were qualified and quantified by Qubit and qPCR. After concentration adjustment, the libraries were mixed and denatured for sequencing.

Sequence preprocessing

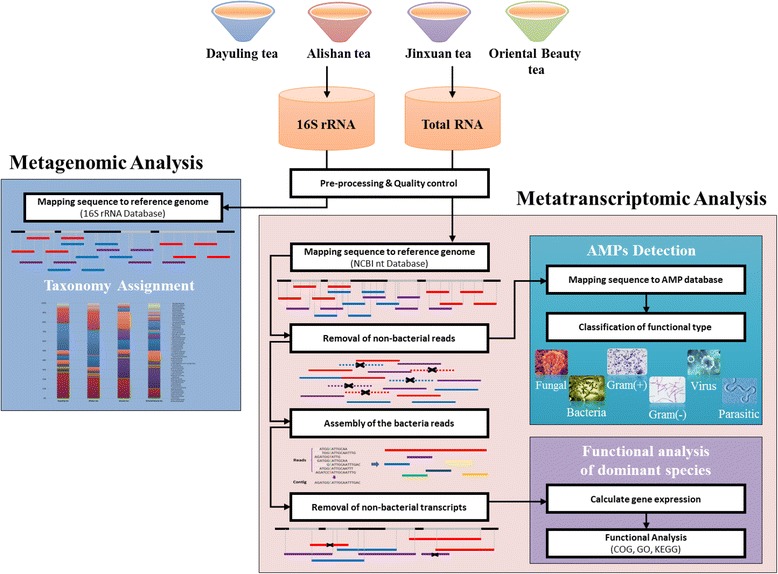

Figure 1 shows our analysis flow. Raw reads were preprocessed using the FASTX-Toolkit (a FASTQ/A short-reads pre-processing tools) [24] to trim poor-quality bases. Nucleotides with Phred quality scores lower than 30 were trimmed from the end of the read, and reads longer than 70 nucleotide bases were retained for subsequent filtering. Reads with 70% of their bases, showing quality score higher than 30, were reserved for further analysis. A quality score (Q) less than 30 corresponds to an error probability (P) of 0.001 according to the formula:

Fig. 1.

Analytical flowchart of the integrated metagenomic and metatranscriptomic pipeline

Taxonomic assignment of 16S rRNA sequences

Paired-end sequences were obtained by Illumina sequencing in FASTQ format and the FASTX-Toolkit was applied for sequence quality assessment. Bowtie2 [25] was used to map the paired-end reads to bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences obtained from the NCBI 16S ribosomal RNA sequence database and NCBI nucleotide collection database. The reads were mapped to specific bacteria if sequence similarity exceeded 97% and paired-end reads were aligned to the same reference sequence.

Functional analysis of transcripts

Next, processed reads from each tea sample were aligned to reference genome sequences using Bowtie2 [21] to bacterial sequences. Reference genome sequences were built from the nt database, which is available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website, including NCBI genome sequences, Ensembl genome sequences, etc. Because of the high degrees of similarity among bacterial genome sequences, the extracted bacterial reads were assembled into contigs by Trinity [26] and aligned to the reference genome again to discard non-bacterial transcripts. The remaining bacterial transcripts were subjected to taxonomy analysis to identify the distribution of bacteria in each sample. Dominant E. coli species were selected for further analysis. To obtain an overview of the functional classes among all samples, we performed Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) analysis using BLASTX to map the sequences against the COG database [27]. Sequencing reads were identified by Bowtie2 and BLASTX as being associated with a certain transcript. Those showing the highest identity with the sequences in the COG database were selected to represent each transcript. Additionally, the dominant bacterial species in oolong teas were selected for functional analysis. Gene expression levels were calculated and normalized using RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization) [28]. Next, gene ontology (GO) analysis was conducted to examine the differences in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions of the dominant species among the four tested tea samples. Finally, genes expressed across all four tea samples were selected for KEGG analysis [29].

Identification of antimicrobial peptides using high-throughput transcriptome data

In this study, we identified 4744 experimentally verified AMPs (Table 1) in published databases, including ADAM [30], CAMP [31], and APD [32]. All collected amino acid sequences of AMPs were transformed into DNA sequences to implement an efficient pipeline for discovering AMPs on NGS reads using the Bowtie2 program. The raw reads of metatranscriptomics data (total RNA) were subjected to quality control and adjustment. After quality control and removing ribosomal RNA and the reads from plants, all reads were mapped to the AMP database and showed a sequence identity of 100%. We provide all of parameters used by those programs in Additional file 1.

Table 1.

Data statistics of validated AMPs in different functional types

| Functional type | Number of AMPs |

|---|---|

| Antibacterial | 3273 |

| Anti-Gram (+) | 2684 |

| Anti-Gram (−) | 2482 |

| Antifungal | 1563 |

| Antiviral | 286 |

| Antiparasitic | 111 |

| Total | 4744 |

Results and discussion

Bacteria taxonomy assignment using 16S rRNA sequences

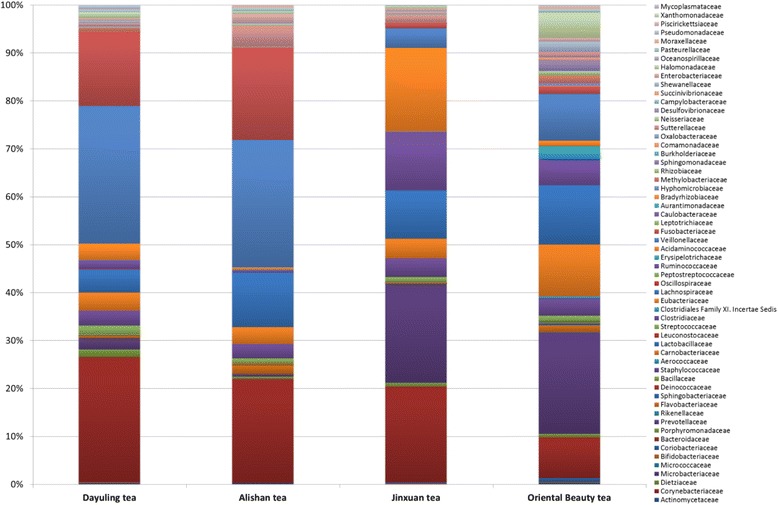

A total of 60,260 sequence reads in the 16S rRNA V4 region were identified using our taxonomic mapping flow from 4 samples with a median read length of 125 base pairs and mean of 15,065 reads per tea sample. Fig. 2 and Table 2 show the bacterial taxonomy assignments at the family level, and operational taxonomic unit tables mapped at different taxonomy levels are provided as Additional file 2. As shown in Fig. 2, bacteria communities present in Dayuling tea and Alishan tea were similar. Veillonellaceae belongs to the phylum Firmicutes as the dominant bacteria. The most distinct feature of the Veillonellaceae family is that it contains bacteria with a gram-negative cell wall structure within a phylum of gram-positive bacteria, and thus, molecular-based methods may be required to identify the species [33]. Interestingly, the family isolates displayed various resistance patterns to antimicrobial agents [34]. Bacteroidaceae was a subdominant family classified in the phylum Bacteroidetes. As previously reported, both Veillonellaceae and Bacteroidaceae were not affected by tea polyphenols [35]. Polyphenols are natural plant compounds present in green and black tea and are associated with beneficial effects such as the prevention of cardiovascular diseases [36] and several food-borne pathogenic bacteria [37]. However, Oriental Beauty tea exhibited significantly higher bacterial diversity than other teas, with Prevotellaceae as the dominant family. De Filippo et al. found Prevotella accounted for more than half of the gut bacteria in African children but was absent in European children; this genus enables the host to maximize energy intake from fibers and confers protection against inflammations and noninfectious colonic diseases [38]. Furthermore, metagenomic analysis results showed that the most common bacterial families across all tea types were Bacteroidaceae (21.7%), Veillonellaceae (22%), and Fusobacteriaceae (12.3%). Additionally, the family Lachnospiraceae was present in all samples. All species in this family are associated with obesity and may protect against colon cancer by producing butyric acid [39].

Fig. 2.

Bacterial communities in four tea samples using 16S metagenomic data

Table 2.

Abundance (number of reads) of bacterial 16S rRNA at the family level for all tea samples

| Family | Dayuling tea | Alishan tea | Jinxuan tea | Oriental Beauty tea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reads | % | Reads | % | Reads | % | Reads | % | |

| Actinomycetaceae | 35 | 0.10% | 13 | 0.10% | 4 | 0.00% | 7 | 0.10% |

| Corynebacteriaceae | 7 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% |

| Dietziaceae | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Microbacteriaceae | 18 | 0.10% | 8 | 0.10% | 9 | 0.10% | 15 | 0.20% |

| Micrococcaceae | 19 | 0.10% | 1 | 0.00% | 4 | 0.00% | 6 | 0.10% |

| Bifidobacteriaceae | 17 | 0.10% | 1 | 0.00% | 12 | 0.10% | 5 | 0.10% |

| Coriobacteriaceae | 12 | 0.00% | 9 | 0.10% | 18 | 0.20% | 73 | 0.80% |

| Bacteroidaceae | 7783 | 26.20% | 2841 | 21.70% | 1660 | 19.90% | 771 | 8.50% |

| Porphyromonadaceae | 474 | 1.60% | 60 | 0.50% | 70 | 0.80% | 63 | 0.70% |

| Prevotellaceae | 704 | 2.40% | 70 | 0.50% | 1715 | 20.50% | 1918 | 21.10% |

| Rikenellaceae | 2 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 5 | 0.10% | 6 | 0.10% |

| Flavobacteriaceae | 116 | 0.40% | 255 | 1.90% | 15 | 0.20% | 135 | 1.50% |

| Sphingobacteriaceae | 31 | 0.10% | 5 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.10% | 40 | 0.40% |

| Deinococcaceae | 0 | 0.00% | 14 | 0.10% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Bacillaceae | 20 | 0.10% | 7 | 0.10% | 2 | 0.00% | 6 | 0.10% |

| Staphylococcaceae | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Aerococcaceae | 0 | 0.00% | 10 | 0.10% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Carnobacteriaceae | 31 | 0.10% | 19 | 0.10% | 3 | 0.00% | 11 | 0.10% |

| Lactobacillaceae | 7 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 17 | 0.20% |

| Leuconostocaceae | 7 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Streptococcaceae | 557 | 1.90% | 137 | 1.00% | 86 | 1.00% | 106 | 1.20% |

| Clostridiaceae | 917 | 3.10% | 387 | 3.00% | 326 | 3.90% | 330 | 3.60% |

| Clostridiales Family XI. Incertae Sedis | 13 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 36 | 0.40% |

| Eubacteriaceae | 1115 | 3.80% | 453 | 3.50% | 339 | 4.10% | 986 | 10.80% |

| Lachnospiraceae | 1416 | 4.80% | 1488 | 11.40% | 834 | 10.00% | 1125 | 12.40% |

| Oscillospiraceae | 17 | 0.10% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | 2 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 4 | 0.00% |

| Ruminococcaceae | 546 | 1.80% | 62 | 0.50% | 1006 | 12.10% | 503 | 5.50% |

| Erysipelotrichaceae | 24 | 0.10% | 12 | 0.10% | 5 | 0.10% | 233 | 2.60% |

| Acidaminococcaceae | 1003 | 3.40% | 64 | 0.50% | 1451 | 17.40% | 106 | 1.20% |

| Veillonellaceae | 8553 | 28.80% | 3487 | 26.60% | 338 | 4.00% | 878 | 9.70% |

| Fusobacteriaceae | 4621 | 15.60% | 2528 | 19.30% | 89 | 1.10% | 150 | 1.60% |

| Leptotrichiaceae | 23 | 0.10% | 18 | 0.10% | 1 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% |

| Caulobacteraceae | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Aurantimonadaceae | 3 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Bradyrhizobiaceae | 5 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 17 | 0.20% |

| Hyphomicrobiaceae | 9 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 38 | 0.40% |

| Methylobacteriaceae | 203 | 0.70% | 20 | 0.20% | 16 | 0.20% | 155 | 1.70% |

| Rhizobiaceae | 58 | 0.20% | 3 | 0.00% | 4 | 0.00% | 86 | 0.90% |

| Sphingomonadaceae | 64 | 0.20% | 18 | 0.10% | 3 | 0.00% | 210 | 2.30% |

| Burkholderiaceae | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% |

| Comamonadaceae | 14 | 0.00% | 6 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 45 | 0.50% |

| Oxalobacteraceae | 9 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 9 | 0.10% |

| Sutterellaceae | 114 | 0.40% | 547 | 4.20% | 129 | 1.50% | 100 | 1.10% |

| Neisseriaceae | 23 | 0.10% | 37 | 0.30% | 7 | 0.10% | 4 | 0.00% |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | 31 | 0.10% | 2 | 0.00% | 21 | 0.30% | 11 | 0.10% |

| Campylobacteraceae | 4 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% |

| Succinivibrionaceae | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 19 | 0.20% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Shewanellaceae | 122 | 0.40% | 20 | 0.20% | 16 | 0.20% | 194 | 2.10% |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 142 | 0.50% | 258 | 2.00% | 53 | 0.60% | 62 | 0.70% |

| Halomonadaceae | 384 | 1.30% | 68 | 0.50% | 40 | 0.50% | 481 | 5.30% |

| Oceanospirillaceae | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Pasteurellaceae | 142 | 0.50% | 91 | 0.70% | 9 | 0.10% | 69 | 0.80% |

| Moraxellaceae | 15 | 0.10% | 59 | 0.50% | 3 | 0.00% | 48 | 0.50% |

| Pseudomonadaceae | 267 | 0.90% | 8 | 0.10% | 11 | 0.10% | 17 | 0.20% |

| Piscirickettsiaceae | 7 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Xanthomonadaceae | 3 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 13 | 0.10% |

| Mycoplasmataceae | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

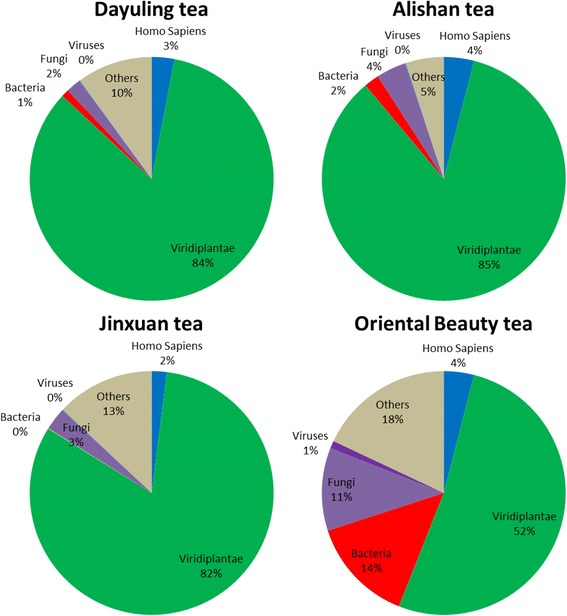

Analysis of transcripts mapped to taxonomy terms

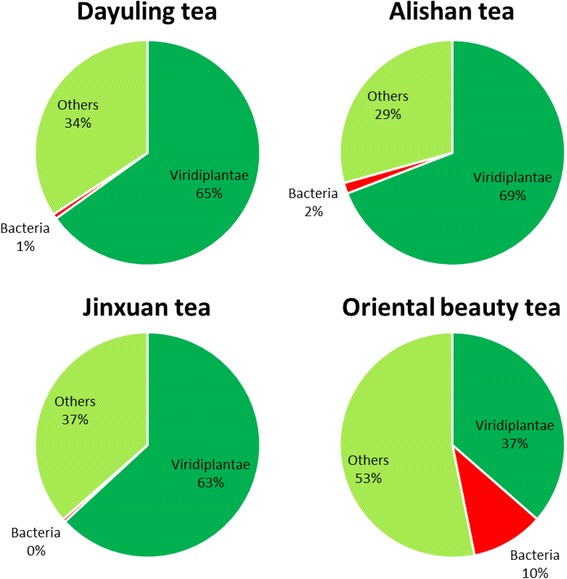

A total of 166,429,720 reads were generated during sequencing, and 80,945,719 reads remained after quality control with a minimum quality cutoff of 20 (Table 3). Reference genome sequence alignments were performed and approximately 80% of the processed reads were assigned a specific kingdom. The read distribution among Homo sapiens (3.26%), Viridiplantae (75.41%), bacteria (4.48%), fungi (5.05%), viruses (0.41%), and others (11.40%) in four samples are depicted in Fig. 3. The percentage distribution of reads in different kingdoms among samples was analyzed. The number of reads mapped to H. sapiens was more balanced across all samples than those assigned to other groups. For example, as expected, most reads were assigned to Viridiplantae with more than 80% from most samples except for Oriental Beauty tea, in which only half of the processed reads were assigned to Viridiplantae (51.6%). Furthermore, compared to the other tea samples, the differences in the percentage distribution of the reads across different kingdoms was greater for Oriental Beauty tea. The balance distribution of reads belonging to H. sapiens across the four tea types can be explained by the short period of contamination from tea farmers during harvest, and the greater biological diversity in Oriental Beauty tea may be related its growth on flat land rather than on the mountains like the other three teas. Among the four samples, 2,038,548 reads were assigned to bacteria and further analyzed.

Table 3.

Kingdom taxonomic analysis of metatranscriptomic data

| Raw reads | QC reads | QC% | Homo sapiens | Viridiplantae | Bacteria | Fungi | Viruses | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dayuling tea | 41,894,931 | 18,100,972 | 43.21 | 458,281 | 11,761,339 | 125,475 | 318,656 | 12,841 | 1,406,717 |

| Alishan tea | 41,152,352 | 27,498,256 | 66.82 | 1,004,044 | 18,979,598 | 425,288 | 831,025 | 23,668 | 1,077,615 |

| Jinxuan tea | 42,728,182 | 21,780,331 | 50.97 | 276,372 | 13,713,125 | 94,797 | 550,722 | 3855 | 2,167,244 |

| Oriental Beauty tea | 40,654,255 | 13,566,160 | 33.37 | 349,091 | 4,940,454 | 1,392,988 | 1,047,815 | 134,282 | 1,711,734 |

Fig. 3.

Kingdom assignments of four tea samples using total transcripts

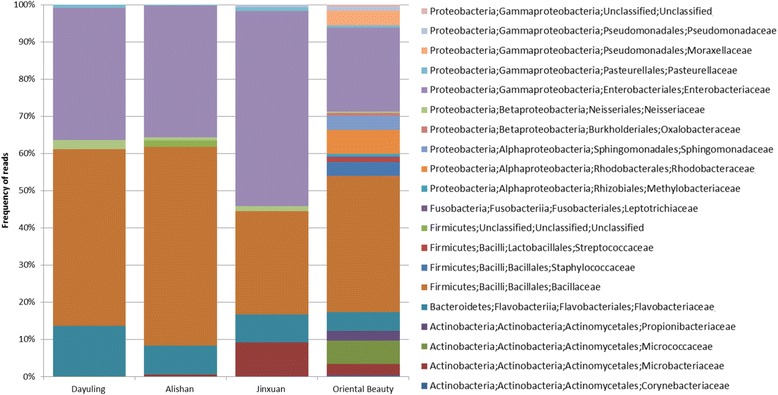

To examine the distribution of bacteria in the four oolong teas, the extracted bacterial reads were assembled using Trinity and aligned to the nt database again to overcome the problem of high sequence similarity among different bacterial genomes. After assembly, 800 contigs were generated and 70 were removed. We counted the reads on each contig to generate the distribution of bacteria in reads as a unit. The top 20 major categories were selected to draw the distribution of bacteria as shown in Fig. 4. The results of taxonomy assignment at the family level indicated that members of Bacillaceae and Enterobacteriaceae were the most abundant microorganisms, comprising 42% and 36% of the bacterial communities among the tea samples, respectively. Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, and Jinxuan tea shared similarities in the distribution of Bacillaceae and Enterobacteriaceae, with the former showing approximately 50% and the latter showing 35%. While more than 52% of the bacterial community in Jinxuan tea was composed of Enterobacteriaceae, the same family accounted for only 22% of the bacteria found in Oriental Beauty tea. In addition, Oriental Beauty tea showed greater microbial diversity at the family level. For example, 7% of the reads were assigned to Rhodobacteraceae, Micrococcaceae in the Oriental Beauty tea sample, but were not detected in the other teas. Furthermore, nearly 10% of the reads belonged to Flavobacteriaceae in most of the tested tea samples, but the same family was found in less than 5% in Oriental Beauty tea. According to Table 3, the differences in the percentage distribution of the reads across the different kingdoms appeared to be more dramatic for Oriental Beauty tea compared to the other three tea samples. Additionally, by extending our observations to bacterial community analysis using metagenomics and metatranscriptomic data, Shannon’s diversity index [40] was calculated to determine the number of different species in a community while taking into account how evenly the basic entities were distributed among those types, according to the formula:

Fig. 4.

Taxonomic distribution of all bacterial transcripts at family level based on metatranscriptomics analysis

As provided in Table 4, the index values indicated that Oriental beauty had the highest species diversity compared to the other three samples. This may be because Oriental Beauty tea is grown at lower altitudes than the other three teas, and its leaves have been bitten by the leaf hoppers.

Table 4.

Shannon’s diversity index of bacterial communities in four oolong teas

| Data type | Dayuling | Alishan | Jinxuan | Oriental beauty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Data | 2.92 | 2.73 | 3.34 | 3.79 |

| Metatranscriptomic Data | 1.76 | 1.19 | 1.66 | 3.08 |

Functional analysis of transcripts of dominant bacterial species

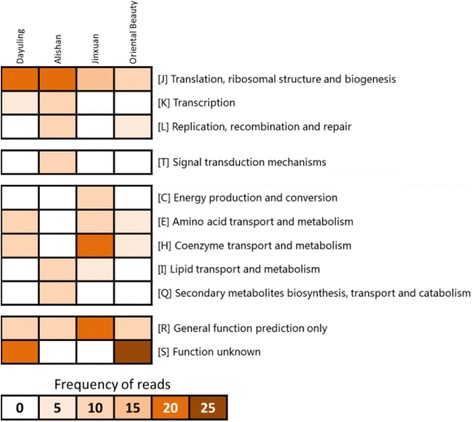

To identify the dominant bacterial species for functional analysis, taxonomy was determined at the species level (Additional file 3: Figure S1). Although the microbial diversity of Oriental Beauty tea was greater at the family level, at the species level all four tea samples appeared to share two dominant bacterial species: E. coli and Bacillus subtilis. To acquire an overview of the functional categories among the tea samples, we assigned each transcript to its corresponding COG category using BlastX (Fig. 5). Most reads were associated with translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis; this may be because of conservation of the rRNA sequences among bacterial species. The functions of more than 20% of the reads in Dayuling and Oriental Beauty teas remain unknown. Some of the identified bacterial protein sequences have not been curated in the current COG database, such as a protein in species Bacillus atrophaeus present in both Dayuling and Oriental Beauty teas.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of COG functional annotations of all bacterial transcripts

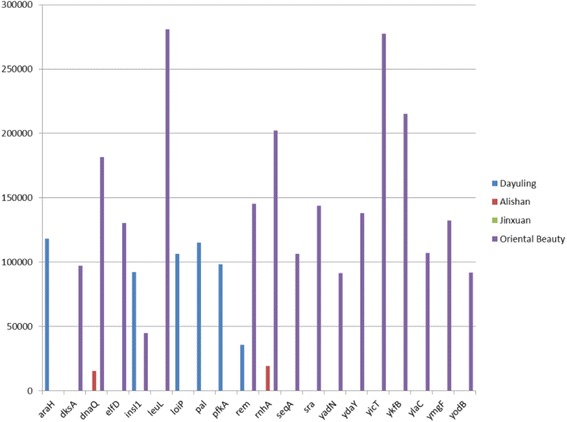

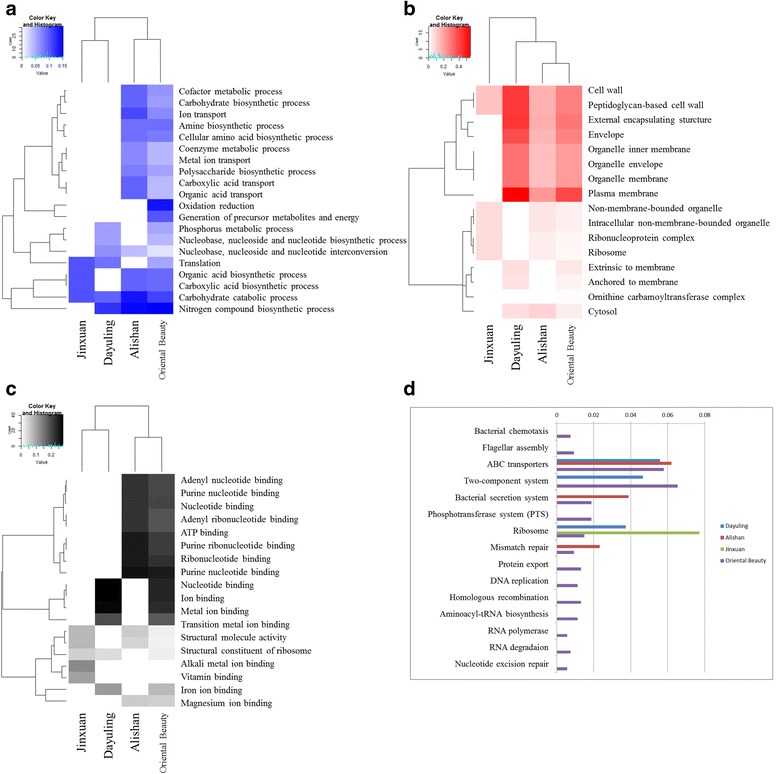

Due to the abundance of gene annotations in public domain, E. coli was subjected to further functional analysis. Based on RSEM gene expression calculations, 962 coding genes were expressed in E. coli (Additional file 4). The most highly expressed genes (top 20) are shown in Fig. 6. Gene Ontology enrichment was using DAVID functional annotation tool [41], which performs a gene- annotation enrichment analysis of the set of differentially expressed genes (adjusted fold change > = 2 and FDR < 0.001). MeV is an open source Java application which contains many popular analytical algorithms for clustering and visualization [42]. It has been used to visualize the clustering result of GO among 4 tea samples. This was performed to identify the biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions associated with these genes (Additional file 5). Figure 7a indicates that while the most actively expressed E. coli genes in Dayuling and Jinxuan resembled each other in biological processes, those present in Alishan and Oriental Beauty seemed to be more similar. However, the results of cellular components (Fig. 7b) and molecular functions (Fig. 7c) analysis showed greater differences among the four teas. The KEGG results (Fig. 7d) showed that E. coli in Oriental Beauty tea is involved in the largest number of pathways; this may be because of Oriental Beauty tea’s growing environment or heavy fermentation process required to produce the tea. Moreover, E. coli in Alishan and Oriental Beauty teas was involved in similar pathways, such as ABC transporters, bacterial secretion system, mismatch repair, purine metabolism, thiamine metabolism, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, as well as alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, nitrogen metabolism, and tryptophan metabolism.

Fig. 6.

Intensity of top 20 highly-expressed genes in the dominant bacterial species

Fig. 7.

GO analysis and KEGG analysis of transcripts of the dominant bacterial species: a Biological process, b Cellular component, c Molecular function, and d KEGG pathway

Identification of natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria in Taiwanese oolong teas

Many methods and tools can be used to perform metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data analysis. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages, particularly with regard to optimization for different study objectives, such as taxonomic profiling, assessing microbial composition, or identifying functional genes and pathways. For instance, the UPARSE pipeline constructs a set of operational taxonomic unit representative sequences from NGS amplicon reads that can be used to understand the microbial community structure [43]. QIIME is a software that allows users to input raw sequencing data generated on multiple platforms and interprets the data from fungal, viral, bacterial, and archaeal communities and provides a visualized version of the results [44]. MG-RAST server is a SEED-based environment that allows users to upload raw sequence data for automatic analysis of microbial community structure and function [45]. In contrast, we designed a database-assisted system for identifying AMPs and their functional types based on metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data. This is a first study to identify natural antimicrobial peptides in bacteria through metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses.

After quality control and removal of non-bacterial reads, the remaining reads were aligned to the AMP dataset, as presented in Tables 5, and 8194 (6.5%), 26,220 (6.1%), 5703 (5.8%), and 10,6183 (7.8%) reads were mapped to AMPs with a sequence identity of 100%. The Oriental Beauty tea sample showed greater microbial diversity at the family level. For example, 7% of the reads were assigned to Rhodobacteraceae, Micrococcaceae in the Oriental Beauty tea sample, whereas none were found in the other teas. Furthermore, nearly 10% of the reads belonged to Flavobacteriaceae in most of the tested tea samples, but the same family was found in less than 5% in Oriental Beauty tea. Oriental Beauty tea contains different bacterial communities possibly because it is grown without pesticides, causing the tea green leafhopper (J. formosana) to feed on the leaves, stems, and buds [23]. Figure 8 shows that the Oriental Beauty tea had a higher percentage of bacterial AMPs (10%) when comparing with other three teas. With a more detailed investigation into the functional types of AMPs, it is very interesting that the distribution of anti-gram-positive and anti-gram-negative AMPs is highly correlated with the distribution of gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial in the four oolong tea samples (Fig. 9). Further, dominant bacterial taxa secrete anti-gram positive or negative AMPs against other bacterial species. For instance, a certain percentage of the reads mapped to AMPs belonging to the dominant bacterial family Moraxellaceae in Oriental Beauty tea, regardless of the functional types of AMPs that were mapped (Table 6).

Table 5.

Data statistics of total RNA reads for AMPs mapping

| Dayuling | Alishan | Jinxuan | Oriental beauty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of mapped reads (%) | 8194 (6.5%) | 26,220 (6.1%) | 5703 (5.8%) | 106,183 (7.8%) |

| Number of AMPs | 876 | 1130 | 761 | 1678 |

Fig. 8.

Data distribution of total RNA reads mapped to AMPs in four Taiwanese oolong teas

Fig. 9.

The distribution of anti-gram-positive and anti-gram-negative AMPs is highly correlated with the distribution of gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial in four oolong tea samples

Table 6.

Number of RNA reads for mapping different functional types of AMP in Oriental Beauty tea

| Family | Reads mapped to Anti-Gram (+) | Reads mapped to Anti-Gram (−) |

|---|---|---|

| Moraxellaceae | 420 | 399 |

| Pseudomonadaceae | 409 | 179 |

| Sphingomonadaceae | 377 | 358 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 369 | 251 |

| Bacillaceae | 234 | 81 |

| Sphingobacteriaceae | 166 | 160 |

| Oxalobacteraceae | 164 | 157 |

| Burkholderiaceae | 151 | 109 |

| Methylobacteriaceae | 150 | 142 |

| Caulobacteraceae | 149 | 20 |

| Micrococcaceae | 117 | 109 |

| Propionibacteriaceae | 117 | 73 |

Conclusions

In this study, four types of Oolong teas (Dayuling tea, Alishan tea, Jinxuan tea, and Oriental Beauty tea) were collected for 16S ribosomal DNA and total RNA extraction and sequencing. An integrated analysis flow was constructed to identify AMPs and their functional types based on metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of high-throughput transcriptome data. Metagenomics analysis results revealed that bacterial diversity was higher in Oriental Beauty tea than in the other teas. This may be because Oriental Beauty tea leaves are often infested with J. formosana, which may contribute to its uniqueness [19] and cause its flavor to be quite different than the other three teas. The results also showed that Dayuling tea and Alishan tea contained similar bacteria communities, and the most common bacterial families across all tea types were Bacteroidaceae (21.7%), Veillonellaceae (22%), and Fusobacteriaceae (12.3%).

Metatranscriptomics analysis results revealed that the dominant bacterial species across all tea types were E. coli, B. subtilis, and Chryseobacterium sp. StRB126. Escherichia coli is the most common bacteria and among the most important bacteria in the human gut [46]. Under normal conditions, E. coli are not only harmless, but also may be helpful to humans. In addition to facilitating vitamin synthesis and immune system development in humans, they also help prevent invasion by harmful bacteria. Bacillus subtilis is a commensal bacterium in the human gut. Previous studies showed that B. subtilis produces subtilisin, polymyxin, nystatin, gramicidin, and other active substances during cell growth and that these substances provide significant protection against food-borne pathogens [47]. In addition to the dominant bacteria described above, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, which was found to be present in only Oriental Beauty tea, is known to produce various secondary metabolites including aminoglycosides, β-lactams, polyketides, and small polypeptides, all of which have been shown to inhibit different pathogens [48]. GO analysis and metabolic network analysis was performed to determine the relationship between dominant functional microbial species and the environment.

Additionally, the results indicated that anti-gram-positive AMPs in Oriental Beauty tea had a higher volume of distribution than in the other three teas. Interestingly, we also found that Oriental Beauty tea contained the lowest proportion of gram-positive bacteria at the family level. This may be because Oriental Beauty tea is grown at lower altitudes compared to the other teas. Alternatively, Oriental Beauty tea leaves are often infested with J. formosana, which may contribute to its uniqueness.

This is the first study to analyze microbial diversity in Taiwanese oolong teas using metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches and to identify natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria in Taiwanese oolong teas. These results contribute to the current understanding of microbes and their potential functions in oolong tea.

Additional files

All of parameters used for analytic programs in each step. (DOCX 13 kb)

The list of operational taxonomic unit at different taxonomy levels. (XLSX 20 kb)

Taxonomic distribution of all bacterial transcripts at species level based on metatranscriptomics analysis. (DOCX 268 kb)

Expression of coding genes in E. coli calculating by RSEM. (XLSX 43 kb)

The results of Gene Ontology enrichment analysis. (XLSX 83 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Publication charge for this work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan under contract number of MOST106–2221-E-155-063 to TYL.

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI SRA repository: 16S rRNA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP113401) and total RNA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP113601).

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Systems Biology Volume 11 Supplement 7, 2017: 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics (InCoB 2017): Systems Biology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcsystbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-11-supplement-6.

Authors’ contributions

TYL and THC conceived and designed the experiments. KYH, JHJ, and YHC performed the experiments. KYH and JHJ analyzed the data. KYH, THC, JHJ, and WCL wrote the manuscript with revision by TYL, CLC, and KRL. KYH and THC contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12918-017-0503-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Kai-Yao Huang, Email: kaiyao.tw@gmail.com.

Tzu-Hao Chang, Email: kevinchang@tmu.edu.tw.

Jhih-Hua Jhong, Email: euphoria5270@gmail.com.

Yu-Hsiang Chi, Email: e75608@hotmail.com.

Wen-Chi Li, Email: hoaytu0128@gmail.com.

Chien-Lung Chan, Email: clchan@saturn.yzu.edu.tw.

K. Robert Lai, Email: krlai@saturn.yzu.edu.tw

Tzong-Yi Lee, Email: francis@saturn.yzu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Zhang G, Ross CR, Blecha F. Porcine antimicrobial peptides: new prospects for ancient molecules of host defense. Vet Res. 2000;31(3):277–296. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Smet K, Contreras R. Human antimicrobial peptides: defensins, cathelicidins and histatins. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27(18):1337–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-0936-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao X, Wu H, Lu H, Li G, Huang Q. LAMP: a database linking antimicrobial peptides. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan ML, Ling KH, Wang MF, El-Nezami H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves epithelial barrier function by inducing the production of antimicrobial peptide pBD-1 and pBD-2 in monolayers of porcine intestinal epithelial IPEC-J2 cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(5):1048–1058. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyu C, Chen C, Ge F, Liu D, Zhao S, Chen D. A preliminary metagenomic study of puer tea during pile fermentation. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93(13):3165–3174. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han LK, Takaku T, Li J, Kimura Y, Okuda H. Anti-obesity action of oolong tea. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(1):98–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ooshima T, Minami T, Aono W, Tamura Y, Hamada S. Reduction of dental plaque deposition in humans by oolong tea extract. Caries Res. 1994;28(3):146–149. doi: 10.1159/000261636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohmori Y, Ito M, Kishi M, Mizutani H, Katada T, Konishi H. Antiallergic constituents from oolong tea stem. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18(5):683–686. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu QY, Hackman RM, Ensunsa JL, Holt RR, Keen CL. Antioxidative activities of oolong tea. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(23):6929–6934. doi: 10.1021/jf0206163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen Q, Liu S. Variation of the microorganism groups during the pile-fermentation of dark green tea. J Tea Sci. 1991;11:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.HJ ZHOU, JH LI, LF ZHAO, Han J, XJ YANG, YANG W, XZ WU. Studyonmainmicrobes on quality formation of Yunnan puer tea during pile-fermentation process. J Tea Sci. 2004;24:212–248. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X, Yan M, Zhu Y. Influence of fungal fermentation on the development of volatile compounds in the Puer tea manufacturing process. Eng Life Sci. 2005;5:382–386. doi: 10.1002/elsc.200520083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitra S, Rupek P, Richter DC, Urich T, Gilbert JA, Meyer F, Wilke A, Huson DH. Functional analysis of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes using SEED and KEGG. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marioni JC, Mason CE, Mane SM, Stephens M, Gilad Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 2008;18(9):1509–1517. doi: 10.1101/gr.079558.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung JY, Lee SH, Jin HM, Hahn Y, Madsen EL, Jeon CO. Metatranscriptomic analysis of lactic acid bacterial gene expression during kimchi fermentation. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;163(2–3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetti A, Schruth DM, Durkin CA, Parker MS, Kodner RB, Berthiaume CT, Morales R, Allen AE, Armbrust EV. Comparative metatranscriptomics identifies molecular bases for the physiological responses of phytoplankton to varying iron availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(6):E317–E325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118408109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason OU, Hazen TC, Borglin S, Chain PS, Dubinsky EA, Fortney JL, Han J, Holman HY, Hultman J, Lamendella R, et al. Metagenome, metatranscriptome and single-cell sequencing reveal microbial response to Deepwater horizon oil spill. ISME J. 2012;6(9):1715–1727. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurice CF, Haiser HJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Xenobiotics shape the physiology and gene expression of the active human gut microbiome. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, Ojesina AI, Jung J, Bass AJ, Tabernero J, et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PA, Koskinen K, Paulin L, Pekkonen E, Haapaniemi E, Kaakkola S, Eerola-Rautio J, Pohja M, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson's disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord. 2015;30(3):350–358. doi: 10.1002/mds.26069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho JY, Mizutani M, Shimizu B, Kinoshita T, Ogura M, Tokoro K, Lin ML, Sakata K. Chemical profiling and gene expression profiling during the manufacturing process of Taiwan oolong tea “oriental beauty”. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71(6):1476–1486. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon A. aGJH: Fastx-toolkit. FASTQ/A short-reads preprocessing tools. 2010;

- 25.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(8):1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HT, Lee CC, Yang JR, Lai JZ, Chang KY. A large-scale structural classification of antimicrobial peptides. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:475062. doi: 10.1155/2015/475062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waghu FH, Barai RS, Gurung P, Idicula-Thomas S. CAMPR3: a database on sequences, structures and signatures of antimicrobial peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1094–D1097. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Li X, Wang Z. APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1087–D1093. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutcliffe IC. A phylum level perspective on bacterial cell envelope architecture. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18(10):464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchandin H, Jean-Pierre H, Campos J, Dubreuil L, Teyssier C, Jumas-Bilak E. nimE gene in a metronidazole-susceptible Veillonella sp. strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(8):3207–3208. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3207-3208.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto T. Chemistry and applications of green tea. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negishi H, JW X, Ikeda K, Njelekela M, Nara Y, Yamori Y. Black and green tea polyphenols attenuate blood pressure increases in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Nutr. 2004;134(1):38–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taguri T, Tanaka T, Kouno I. Antimicrobial activity of 10 different plant polyphenols against bacteria causing food-borne disease. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27(12):1965–1969. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(33):14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meehan CJ, Beiko RG. A phylogenomic view of ecological specialization in the Lachnospiraceae, a family of digestive tract-associated bacteria. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6(3):703–713. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shannon CE. The mathematical theory of communication. MD Comput 1997. 1963;14(4):306–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang d W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(25):14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Walters WA, Gonzalez A, Caporaso JG, Knight R: Using QIIME to analyze 16S rRNA gene sequences from microbial communities. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2011, Chapter 10:Unit 10 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Keegan KP, Glass EM, Meyer F. MG-RAST, a metagenomics Service for Analysis of microbial community structure and function. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1399:207–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3369-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ. Competitive exclusion by Bacillus Subtilis spores of salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis and Clostridium Perfringens in young chickens. Vet Microbiol. 2003;94(3):245–256. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsieh FC, Li MC, Kao SS. Evaluation of the inhibition activity of Bacillus Subtilis-based products and their related metabolites against pathogenic fungi in Taiwan. Plant Prot Bull. 2003;45:155–165. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All of parameters used for analytic programs in each step. (DOCX 13 kb)

The list of operational taxonomic unit at different taxonomy levels. (XLSX 20 kb)

Taxonomic distribution of all bacterial transcripts at species level based on metatranscriptomics analysis. (DOCX 268 kb)

Expression of coding genes in E. coli calculating by RSEM. (XLSX 43 kb)

The results of Gene Ontology enrichment analysis. (XLSX 83 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the NCBI SRA repository: 16S rRNA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP113401) and total RNA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=SRP113601).