Summary

There is currently little research into the experiences of those who have undergone bariatric surgery, or how surgery affects their lives and social interactions. Adopting a constructivist grounded theory methodological approach with a constant comparative analytical framework, semi‐structured interviews were carried out with 18 participants (11 female, 7 male) who had undergone permanent bariatric surgical procedures 5‐24 months prior to interview. Findings revealed that participants regarded social encounters after bariatric surgery as underpinned by risk. Their attitudes towards social situations guided their social interaction with others. Three profiles of attitudes towards risk were constructed: Risk Accepters, Risk Contenders and Risk Challengers. Profiles were based on participant‐reported narratives of their experiences in the first two years after surgery. The social complexities which occurred as a consequence of bariatric surgery required adjustments to patients' lives. Participants reported that social aspects of bariatric surgery did not appear to be widely understood by those who have not undergone bariatric surgery. The three risk attitude profiles that emerged from our data offer an understanding of how patients adjust to life after surgery and can be used reflexively by healthcare professionals to support both patients pre‐ and post‐operatively.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, patient experiences, qualitative research, social complexities

What is already known about this subject

Bariatric surgery has a significant impact on a person's life, largely resulting from changes to their physical appearance and eating habits.

There is a paucity of research examining patients’ experiences of how bariatric surgery affects their everyday lives.

What this study adds

This is an in‐depth exploration of patient‐reported social complexities impacting life after bariatric surgery.

The patients’ experience of adjusting to life after bariatric surgery may be highlighted by examining their attitudes towards the social risks encountered in everyday life. This study proposes three risk attitude profiles that may contribute towards a greater understanding of the social complexities of adjusting to life after bariatric surgery.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is an accepted method of facilitating weight loss for adult obesity, with increasing evidence showing a resultant positive impact on other obesity‐related conditions, e.g. Type 2 Diabetes 1. Such findings have resulted in extended NHS eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery to include both those with obesity as well as those with related metabolic disease 2. This has resulted in an increased number of people living with a bariatric surgically altered body. In a societal context, there are high levels of stigma towards people with obesity, which negatively impacts quality of life for those affected 3. However, this stigma may change, but may not disappear, through the rapid and sustained weight loss attributable to surgical intervention

Owing to the significant changes imposed by bariatric surgery on individuals, including altered eating habits and physical appearance, people experience a period of psychosocial adjustment post‐surgically. This is especially important for those who undergo either gastric bypass or gastric sleeve procedures as these cannot generally be reversed. Life after bariatric surgery requires many interpersonal adjustments 4 for the individual; many of these exist outside of routine clinical care and are not as widely understood. These subjective experiences can be captured using qualitative methodologies, which focus on ‘human beings in social situations’ (5, p.17). Bariatric surgery has been positioned, both in guidelines 2 and by patients, as ‘a last resort’, being conceptualized as a transformational process 6, 7. This can affect social relationships 8, 9, 10 and also requires learning to adjust to new ways of eating 11, which may not always be understood by others 12. Studies show that bariatric surgery may give patients more ‘control’ over their lives 13, 14, 15, which may not have been present prior to surgical intervention. The adjustments to life and the impact of significant weight loss may not always be viewed positively despite weight loss 16, 17. Additionally, the media does not always portray bariatric surgery favourably, with terms such as ‘cheating’ and ‘taking the easy way out’ used as descriptors in the lay press 18. This may impact societal perceptions of surgery as a weight‐loss method and of those who undergo these procedures. Overall, the existing body of literature on patient experiences of adjusting to life after bariatric surgery is small, with limitations to studies such as lack of detail of sample groups and broad timeframes that encompass both those who have had surgery recently and those who have had surgery many years previously. Studies also had different methodological aims, with many being descriptive. However, this corpus of literature shows that patients view bariatric surgery as a transformational experience, significantly impacting the lives of those who undergo surgical intervention. Research into the impact of bariatric surgery in social contexts from the patient's perspective is therefore much needed to fully understand patient experiences after surgery.

In the UK, patients are followed up for 2 years postoperatively in bariatric surgical units before being discharged into the community for long‐term care. Owing to the paucity of research into patient experiences of adjusting to life after bariatric surgery and the significant impact of bariatric surgery on a person's life, this study was undertaken to provide an understanding of the social aspects of living with bariatric surgery. This differs from patient experiences of care and biomarkers of surgery, such as weight loss and disease amelioration, which are based on clinical encounters. The aim of this study was to explore how people adjust to the social aspects of their lives in this first 2 years following surgery.

Methods

Design

A qualitative approach was used for the study, which is suitable for understanding the subjective experiences of a phenomenon 19, but our aim was to go beyond this description to explore the complex social processes that appeared to occur after bariatric surgery. Although the description provides detailed information, it does not always show ‘why’ or ‘how’ processes happen, or the contexts informing them. As a result, grounded theory was chosen for its ability to provide an explanatory theory of the phenomenon and the systematic method of constant comparative data analysis, which creates an interactive process of moving back and forth between empirical data and emerging analysis, which focuses data collection and encourages theoretical analysis of the data 20. Grounded Theory is defined as a high‐level conceptual framework that possesses explanatory power underpinned by analytical processes, defined by concepts constructed from it 21. The constructivist version of the method focuses on mutual reciprocity between the researcher and participants, with participants actively shaping and influencing the interviews. The topic guide was a list of open prompts rather than a prescriptive checklist, and the interview was guided by the participants rather than the researcher asking a series of questions. Using grounded theory, analytical techniques such as coding, memoing and constant comparative analysis allowed the research team to go beyond superficial description and find tacit meanings and actions 22 to fully understand the processes involved in the adjustment to life after bariatric surgery. Codes were checked against transcripts, and any ambiguities were clarified by further interaction with the participants. The interpretive rendering is an acknowledged co‐construction between the participant and researcher; the interaction between the two parties in constructing a theoretical explanation means that an external reporting of events is unlikely. In addition, the employment of grounded theory analysis, such as open and focused coding, using gerunds to identify tacit actions, the use of memos to explore concepts constructed from the data and constant comparative analysis techniques, minimizes the possibility of superficial data interpretation 23. Based on these tenets and the aim of the research, constructivist‐grounded theory was deemed to be an appropriate methodology to illuminate the subjective patient experiences in the research.

Initial purposive sampling was used for the first four participants; theoretical sampling was used for the remaining 14 participants, which allowed exploration of the themes constructed from the participant narratives. Data were collected through individual, face‐to‐face, semi‐structured interviews, which are congruent with the constructivist theory approach, allowing the participants to shape and influence the interview process. The interviews were held at a time and place convenient for the participants, who gave written consent for the audio recording of their interviews and for the researcher to take field notes during the interview to capture any concepts the researcher wished to explore further without having to disrupt the flow of the interview. Participants were offered a £15 voucher for participating. All interviews were conducted by the same researcher (YG).

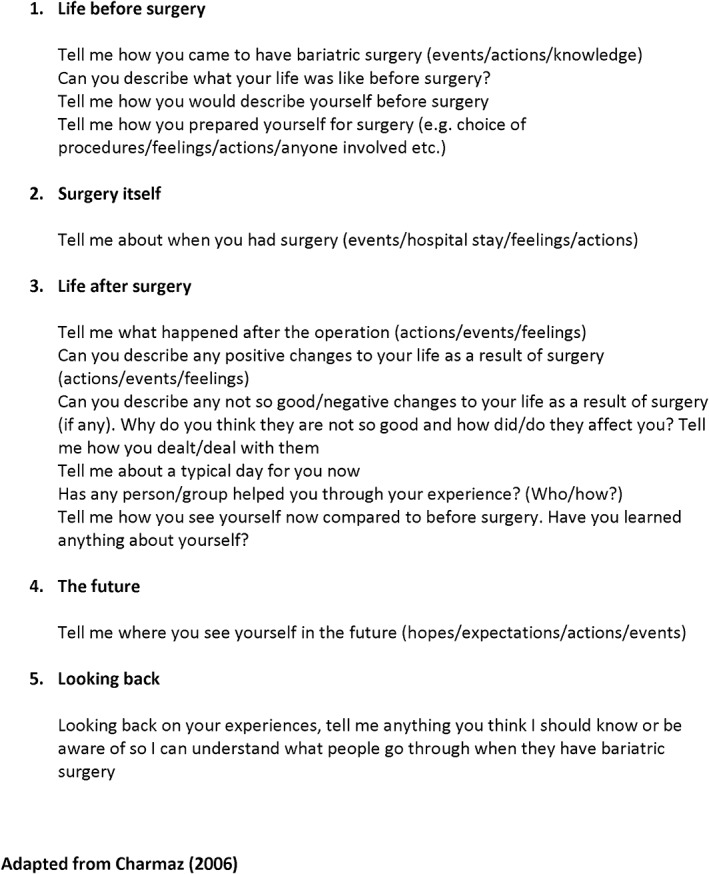

A topic guide with open prompts (see Fig. 1) informed the interviews, which lasted for 45–60 min. Each interview was transcribed verbatim, with identifying information anonymized. Ethical approval was granted by the UK National Health Service, City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Sunderland Research Ethics Committee.

Figure 1.

Topic guide for interviews.

Recruitment

Participants meeting the inclusion criteria (see Table 1) were identified from patient records at a large NHS bariatric surgical service in North East England. Potential participants were contacted by post with a letter of invitation, information about the study, a contact form and Reply Paid envelope. Participants returned the contact form, and interviews were arranged and conducted. Recruitment ceased once theoretical saturation had been achieved, i.e. no further codes were found in the data.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for study

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Adult (≥18 years of age) | Persons ≤18 years of age |

| Up to 2 years post‐surgery at time of interview | After 2 years postoperatively |

| Under the care of hospital | Discharged from hospital |

| Able to provide informed consent | Unable to provide informed consent |

| No active psychological conditions for which treatment is currently being provided | Psychological conditions for which treatment is currently being provided |

| Gastric bypass or gastric sleeve procedure | Gastric band or gastric balloon procedures |

Data analysis

Following each interview, the researcher wrote reflective memos in a journal to record her thoughts about the interview, which is recommended to maintain reflexivity 22. The study team analysed the anonymized transcripts following the constructivist‐grounded theory tenets of open and then focused coding 24. This was performed manually to maintain closeness with the data, and was linked with conceptual mapping, which were visual drawings of the codes, their properties and relation to each other. This was carried out as part of the data analysis. The open coding, focused coding, memoing and conceptual mapping informed the theoretical sampling throughout the constant comparative analytical process. As the data were collected and analysed, the open coding, focused coding, memos and field notes shaped the theoretical direction. Mapping was used to visualize emerging patterns and to understand how concepts may be related to each other, which contributed to theoretical direction. To construct the basic social processes underpinning the adjustment to life after bariatric surgery, the common storyline that underpinned each participant's journey was mapped out. The third stage is theoretical coding, through which theoretical integration turns data into theory. It is defined as ‘applying a variety of analytic schemes to the data to enhance their abstraction’ (25, p.23): the purpose of theoretical coding is to assist with theorizing the data and focused codes and conceptualizing the relationship between them 24. Theoretical coding was used as the final stage in the coding process, which allowed clarification of the ‘general context and specific condition in which the phenomenon is evident’ (24, p.151) to ensure that the events and actions of the participants and the associated underlying meanings were captured.

YG led the initial analysis, but there were discussions between YG and JL in relation to coding; these codes were then discussed with the rest of the study team. Theoretical saturation, defined as ‘the point at which gathering no more data about a theoretical category reveals no new properties nor yields any further theoretical insights about the emerging grounded theory’ (22, p.189), was thought to have been achieved after 15 interviews; however, 3 further interviews were carried out to confirm this.

Results

A total of 18 participants (11 female, 7 male) took part in the study. The post‐surgical time frame at the time of interview ranged from 5 to 24 months. A pre‐ and post‐surgical dichotomy was evident in all narratives. Many participants reported feeling stigmatized as a result of others’ attitudes towards the participants weight prior to surgery:

It isn't very nice being the fattest bloke in the office. I was very self‐conscious about my weight, my co‐workers made fun of me, I tried to laugh it off but it really hurt me. I didn't show it, but I felt it inside (Participant J)

I'd been battling my weight for ten years, losing and gaining. When I went out, people would shout nasty things at me, kids would make fun of me and I was miserable…this went on and on (Participant P)

When I was at my heaviest weight, a couple came in to see me and the husband laughed, pointed at me and said ‘We saw you earlier, and we thought you were the cleaner’. I was well dressed, in my line of work you have to be. It was obvious that thought because I was fat I had to be a cleaner and not a professional person. I felt terrible (Participant Q)

(Reviewer 3, 4B)

Through constant comparative analysis, the focused codes shaped the theoretical codes and their properties (see Table 2), from which the attitudes towards risk were constructed.

Table 2.

Theoretical codes and their properties

| Focused code | Theoretical code | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Failing | Understanding failure as embedded in risk | Worrying about the risk of failing |

| Accepting setbacks as temporary failures that can be rectified | ||

| Not caring about failing | ||

| Moving forward | Adjustment period interpreted as a risk‐laden process both positives and negatives | Accepting and working with the changes that surgery brings |

| Challenging the changes to life imposed by surgery | ||

| Worrying that surgery causes problems | ||

| Finding mechanisms for dealing with awkward situations | ||

| Not regretting the decision to have surgery | ||

| Feeling head and body are reconnected | ||

| Knowledge as empowering and gaining control | ||

| Keeping secrets | The fear of being judged forcing participants to not disclose having surgery | Defining difficult situations and in what contexts they occur |

| Explicating the difficult situations and the reasons underpinning these | ||

| Identifying which participants find certain situations more difficult and why | ||

| Support seeking | Conceptualizing the role of support in the adjustment process | Defining factors affecting support seeking |

| What/who are defined as sources of support | ||

| What are the properties of support seekers and those who do not seek support? |

Once the core theme of risk attitude was agreed upon, further analysis and discussions between the researchers were undertaken. From this, six themes were constructed around participants attitudes towards risks encountered in social interactions after bariatric surgery. In all participants’ narratives, the concept of risk was identified as being evident in their pre‐surgical lives, but remained and took on new meaning after surgery (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The interpretation of risk after bariatric surgery

| Theoretical concepts | Theoretical code | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Failing or giving up | Understanding failure as embedded in risk | Worrying about the risk of failing |

| Accepting setbacks as temporary failures that can be rectified | ||

| Not caring about failing | ||

| Moving forward | Adjustment period interpreted as a risk‐laden process that is both positive and negative | Accepting and working with the changes that surgery brings |

| Challenging the changes to life imposed by surgery | ||

| Finding mechanisms for dealing with awkward situations | ||

| Knowledge as empowering and gaining control | ||

| Feeling uncertain | Framing expectations, worries and beliefs as embedded in risk | Uncertainty is worrying |

| Uncertainty is an accepted part of the adjustment process | ||

| Worrying that surgery causes problems | ||

| Keeping secrets | Fearing that the risk of disclosure about having bariatric surgery will lead to being judged; continuous worries about what others think of them | Defining the difficult situations and in what contexts they occur |

| Explicating the difficult situations and the reasons underpinning these | ||

| What situations are more difficult and why | ||

| Support seeking | Acknowledgement of wanting or not needing support and the risks associated with both during adjustment | Defining factors affecting support seeking |

| What/who are defined as sources of support | ||

| What are the properties of support seekers and those who do not seek support | ||

| Feeling guilty | Reflecting on the effects of their previous obese state and its effect on themselves and others | Making up for lost time |

| Having had surgery (surgery did the work, not the person) | Accepting that surgery is a weight‐loss method that involves the person |

The Risk Attitude profiles

The six themes appeared to have three different interpretations, which we constructed into three profiles: Risk Accepters, Risk Challengers and Risk Contenders. Each profile was underpinned by a difference in attitudes towards the interpretation of social risks after bariatric surgery. The concept of social risk is defined as when ‘individuals weigh up or decide what a risk is, making assessments of the social meaning of the phenomena and their place within cultural norms. They are deciding how these phenomena cohere with their values about what is acceptable and what is harmless against what is dangerous or threatening’ (26, p.638) This was reflected in the actions taken during each social encounter.

A description of each profile follows, with detailed participant characteristics shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Participant characteristics

| Participant | Gender | Age | Status | No. of children | Pre‐op weight (kg); self‐reported | Time from surgery (Mths) | Weight loss (kg) | Type of operation | Risk attitude profile | % of weight lost; self‐reported (%) | Weight at interview (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F | 51 | Married, self‐employed | 3 | 109 | 14 | 32 | Gastric sleeve | Accepter | 28 | 78 |

| C | F | Cohabiting, unemployed | 2 | 128 | 9 | 44 | (mini)Gastric bypass | Accepter | 34.4 | 84 | |

| G | M | 44 | Married, full‐time employed | 2 | 199 | 8 | 47 | Gastric sleeve (balloon first) | Accepter | 23.8 | 152 |

| H | F | 64 | Married, part‐time employed | 3 children, 3 grand‐children | 105 | 5 | 21 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 20.9 | 83 |

| I | F | 60 | Married, unemployed | 3 children, 1 grand‐child | 146 | 12 | 47 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 32.6 | 97 |

| J | M | 47 | Married, full‐time employed | 2 children, 2 grand‐children | 133 | 10 | 47 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 35.7 | 85 |

| L | M | 52 | Widowed, full‐time employed | 2 | 122 | 16 | 47 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 38.8 | 11.8 |

| N | F | 50 | Married, part‐time employed | 2 children, 1 grand‐child | 127 | 15 | 57 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 45 | 11 |

| O | F | 38 | Married, unemployed | 2 | 134 | 13 | 73 | Gastric bypass | Accepter | 54.9 | 9.5 |

| P | M | 36 | Single, unemployed | 0 | 203 | 5 | 48 | Gastric sleeve | Accepter | 23 | 24.5 |

| Q | F | 52 | In a relationship, full‐time employed | 1 | 103 | 6 | 24 | Gastric bypass (conversion from gastric band) | Accepter | 25 | 12.4 |

| R | F | 50 | Single, full‐time employed | 0 | 119 | 24 | 41 | Bypass | Accepter | 37 | 11.4 |

| B | F | Cohabiting, full‐time employed | 1 | 153 | 7 | 53 | Bypass | Contender | 35 | 15.4 | |

| D | F | 47 | Divorced, full‐time employed | 2 | 131 | 14 | 34 | Bypass | Contender | 26.4 | 15.3 |

| E | M | 49 | Single, self‐employed | 0 | 210 | 15 | 51 | Sleeve (after balloon) | Contender | 27.2 | 24.0 |

| K | F | 52 | Cohabiting, unemployed | 2 | 133 | 10 | 29 | Sleeve | Contender | 21.4 | 16.5 |

| M | M | 55 | Married, unemployed | 2 children, 1 grand‐child | 158 | 6 | 19 | Sleeve | Contender | 12.8 | 21.0 |

| F | M | 48 | Cohabiting, unemployed | 0 | 146 | 14 | 44 | Sleeve | Challenger | 30.4 | 16.0 |

The Risk Accepter profile

The Risk Accepters (n = 12) generally reported feeling comfortable in social encounters. A commonly reported situation was eating with others, e.g. in a restaurant. This sometimes involved having to explain why they were eating differently, e.g. when ordering a smaller portion of food or not finishing a meal. During their interviews, the Risk Accepters recalled preparing for surgery and reported a desire to adhere to weight loss and lifestyle targets set by the bariatric surgery team. Risk Accepters were aware that failure to do so would result in them not progressing to surgery, and this was their primary reason for complying with the lifestyle targets that had been set for them:

If I didn't lose the weight they wanted me to, I couldn't have the surgery and I would have been snookered…something just clicked after the seminar [a seminar for bariatric surgery candidates delivered by hospital staff] and I lost the weight, kept it off and lost a little bit more, so then I could have the surgery. (Participant N)

Following surgery, this group of participants understood that changes to their lives were needed to lose weight and that failure to adjust to the surgically imposed life changes would mean the risk of failing to lose weight or a slower weight loss, and their individual expectations of surgery would not be met. It was important for Risk Accepters to comply with the adjustments needed in order to be able to achieve their expectations of surgery. As such, Risk Accepters tended to be disciplined in their approach to post‐surgical life:

I'm not going to do without, but I've got rules. It I do not eat cakes, I don't eat chocolate, sweets, fizzy drinks and I never touch alcohol I know people who eat them, they just water it down with ice so it doesn't fizz up, but I just think I've had my surgery and up to now it has probably cost £25,000, maybe £30,000 by the time you think of the surgery, the doctors, the staff who looked after me.] I'm not prepared to waste that, because I would have stayed [obese], I wouldn't have had the operation, and I've had to make changes [to my life] (Participant C)

Risk Accepters tended to be positive in their outlook and about the required changes to their lives. They recognized that there were difficulties but looked for solutions and ways to lessen these difficulties, which they related to the advice they had to follow after bariatric surgery:

I had a huge problem getting the amount of vegetables in they say you need to have after the operation…it was difficult, but I make soup and you can get them all in there…because you boil them and blend it…they're all in there. Boy, you can get your five a day no problem…chewing was a problem, but not with soup…It's a habit my husband and I have got into with the soup, but the operation and how I feel now, has been absolutely life‐changing. (Participant H)

This positive outlook was reflected in their reported attitudes towards life after bariatric surgery; however, these attitudes were underpinned by realistic expectations and the understanding that there may be difficulties. They felt that learning to deal with these difficulties was part of the adjustment process:

If you go to a restaurant, you still enjoy yourself and the company, but you have a small bit to eat and you're done…like we use food as a reason for going out and talking…a ritual, and then they order poppadoms and someone says have some and I have to say I can't because I need the meat, I need the protein and it's so trivial in the grand scheme of things. Our friends are so supportive. I did make the mistake of overeating once… I've never been a heavy drinker, I just enjoy the social interaction when we go out, but now when we go out for a meal, I feel a bit out of it, but my friends and family know what I've been through, they support me so it's not really a problem. (Participant G)

For this and other participants, going out for a meal had changed postoperatively as surgery meant that eating was different in terms of food choices and portion sizes. Participants acknowledged they were still able to take part in social activities, albeit under changed conditions, but being able to continue their social activities was important to them. Risk Accepters tended to have social support but acknowledged the difficulties associated with disclosing the decision to have surgery, and as we will see, although they were more open about disclosing their decision about surgery than the Risk Contenders, they were also careful about whom they revealed their decision to:

When I am in a restaurant my friends say eating out is a waste of money for me, I say look, I either pay for it, because I'm here with everybody, or I sit here and don't have it and the restaurant staff will think, I bet she's going to pinch something off someone's plate, you know. My friends ask me why I tell the servers and I'll say because I feel like I have to explain why. I know it's just me, but my friend doesn't think I should ever have to explain or have to tell anyone what I'm doing, but I feel I have to. (Participant A)

When asked about looking towards the future, all Risk Accepters reported feeling positive about this:

I will never to go back to where I was, being that big. Never. I will always try and keep my weight down. I will look after my husband the way he's looked after me for all these years. That's what it's all about. (Participant I – Risk Accepter)

There were 12 participants who were classified as Risk Accepters (see Table 4).

The Risk Contender profile

The adjustment process in this cohort appeared to be more difficult than for the other profiles. Risk Contenders (n = 5) reported experiencing setbacks that required actions to help adhere to the post‐surgical advice. Participants reported two types of setbacks: ones that they openly admitted contributing to and incidents out of their control. An example of the former setback was weight gain; this was discussed in terms of admitting the setback was something they had control over and accepting this as a setback, feeling remorseful and wanting to get back on track :

You find you are easily led. Me, I was easily led along that path [not adhering to post‐surgical advice i.e. eating too much or the wrong type of food] and then I think Christ almighty, I shouldn't have done that….you've got to stop…you can't have that stuff anymore, but you are so easily led and that's why I think I've put the weight on…I just need a kick up the ass to get myself back into gear really. You have to be [hard on yourself], I have to be, if I phone the hospital and they say you have to do this, then you've got to do it, that's it…I think Oh God, I have to get myself back into it. (Participant D)

One participant's account was underpinned by his perception of control, which was paramount to his adjustment experience. Participant M had previous health issues that made a gastric bypass too risky a procedure for him to undergo; therefore, a gastric sleeve procedure was performed, and as a result, he had lost a significant amount of weight. However, at the time of interview, he had not lost enough weight to enable him to undergo the back surgery needed to resolve paralysis in his leg. The paralysis prevented him exercising, which would help him to lose more weight; he felt trapped in a situation with factors deemed to be out of his personal control, preventing him from moving forward, and as such, he was contending risk continuously:

I was a bit upset when he [surgeon] said he didn't expect me to lose more than another 5 kilos…I needed to lose weight and be under 123 kilos to be able to have back surgery and when he said he didn't expect me to be less than 130 kilos that was upsetting…I've been waiting for back surgery….and since the bariatric surgery, the wife and I have been having problems, and it's so frustrating, so I've had some chocolate. It's wrong, but since that news from the surgeon I bought 24 cans of beer and I've still got 1 or 2 left. That was 3 months ago, I'm not a big drinker, but it was a downer being told I wouldn't lose as much weight as I wanted to. (Participant M)

This resulted in him dealing with the setback that he would be unlikely to lose more weight by temporarily eating the wrong foods (similar to Participant D) and drinking more alcohol than usual. However, he acknowledged that he had got himself back on track and was now eating sensibly.

Similar to the Risk Accepters, Risk Contenders also expressed the positive effects of weight loss associated with bariatric surgery, comparing these to their lives before surgery:

With big people they sweat a lot and I was conscious of sweating down below…I always had deodorant and a spare pair if my pants got damp. I used to panic. Now I don't worry. There always used to be a damp patch and I would have to spray with deodorant, so that is a big thing for me [after bariatric surgery], to be clean. (Participant K)

The main difference between the Risk Contenders and the other risk types was the worry in situations relating to adjusting to the post‐surgical life changes, despite the processes taking place within the same time as the other types. Risk Contenders acknowledged the problematic situations, but learning to deal with these situations was difficult:

For all my body's stopped eating, my head still wants to eat…and I really struggle with this. I didn't initially, the first six months I was champion [in a positive frame of mind], but since Christmas, all those nibbly bits. I'm thinking ‘Am I going down this route again of eating rubbish?’ I shouldn't be, but I feel, I think because I didn't have chocolate for months I'm thinking I'm not going down that route. I'm not going to eat it because I've got a new chance at life and I'm not going to waste it. (Participant B)

What made the Risk Contenders different from the other constructed risk types were the lack of resolution and/or acceptance of the situation; it was an ongoing process.

Your mind is telling you you're too big, but it's your clothes, they tell you something else, like on an airplane, you don't have to struggle with the seatbelts like before. My belly was hard before surgery and this year when I went away, I felt like I had to try and hide my belly because it's loose now. Its .it's weird, I don't think I will ever get rid of my stomach. I exercise, I go to the gym and I swim. I exercise 5 days a week, I try and get things done when I can, but when I was going to the gym a lot I got dizzy and the nurse said I was burning more calories than I was taking in, but I don't want to put the weight back on so I go to the gym. (Participant O)

People with other risk profiles had found solutions to their dilemmas or had learned to deal with it in a manner that avoided causing them further concern. As with the other risk types, the decision to tell others about undergoing surgery was difficult, and each Risk Contender had people they considered safe to tell and others who they felt were not:

I never told anyone, except my Mum. I just didn't want to be talked about. I didn't want that from anybody, so I made that decision, she is the only person I can talk to about it; she has been really good and supportive. She wasn't at first because she was afraid of losing me on the operating table. I have two children and they don't know a thing. People judge you and I worry what people will think, definitely, even now, I worry more now what people are thinking, more than before. (Participant D)

The other types had found solutions to their dilemmas or had learned to deal with it in a manner that did not cause further concern. Some Risk Contenders had other health issues that could be improved or resolved through the significant weight loss afforded by bariatric surgery, but this had not as yet happened. For example, one Risk Contender was going through a phased approach to bariatric surgical procedures as he was deemed too high a risk for surgery and anaesthesia. He had a gastric balloon inserted to assist with weight loss to make him less of a risk for surgery. Then, because of unforeseen circumstances during the surgery, a gastric sleeve was performed, which will be converted to a bypass eventually:

The gastric sleeve is the first step to the bypass…I want the bypass because I don't ever want to be big again….I don't want to be at a stage where I will lapse back to where I was…it's partly about surgery, partly about changing my lifestyle…it's not going to happen overnight. (Participant E)

Some participants reported feeling guilty about receiving compliments after telling others about surgery being the reason for their changed appearance:

My friend said I looked well and I said, thanks, I've had bariatric surgery, but I feel guilty when people say nice things like that, or I am doing great, keep it up, etcetera. I feel in one way I am expected to lose weight because I've had bariatric surgery. I sometimes feel guilty when they said I look fab, because I think it wasn't me, it was the surgery that made me do it…lose weight that is. Before I told people I used to feel guilty about how people would feel about the NHS paying for me to have surgery, and when I started to get compliments about my appearance I would brush them off because I felt it was the surgery, not me that made me lose weight and I felt guilty (Participant K)

The common theme underlying all these in vivo quotes was the ongoing issues surrounding adjustment, which formed the basis of the Risk Contender profile. However, all Risk Contenders were feeling positive about the future:

I'm looking forward to doing even more things together with my son, not just standing back and watching, I can be part of it all. (Participant K – Risk Contender)

Five participants were categorized as Risk Contenders (see Table 4).

The Risk Challenger profile

One participant's narrative appeared to be different from the Risk Accepter and Risk Contender types in the interpretation of risk (Participant F). He was conceptualized as a Risk Challenger (n = 1) owing to his acknowledgement of the life adjustments required post‐surgically while refusing to adhere to them. He had an overt and openly challenging attitude towards these adjustments, but his ideas were, like other participants, rooted in his pre‐surgical life.

He acknowledged a desire to have what he referred to as a ‘normal life’ as opposed to a life he felt was dictated by the ‘demands’ of adjusting to life after surgery. The Risk Challenger was aware of the recommendations for adjusting to life after bariatric surgery. He stated that, pre‐surgically, he had been aware of the need to commit to diet and lifestyle changes as part of pre‐surgical criteria but appeared to have commenced challenging these preoperatively:

I had to lose weight before surgery. I lost 2 or 3 stone before the operation and in the run up to Christmas I put it all back. I went for my weigh‐in in November or December and I'd lost the weight. I was all geared up to go in for surgery in January, but over Christmas I drank too much and I put my weight back on. I went to get weighed in January and she [nurse] just looked at me and I thought, hey, I've lost more weight and she said no, you've put it back on, you're back to the size when you started, so I had to lose more weight before they would let me have the surgery. I just drank too much over Christmas. (Participant F)

While he understood that failing to lose weight would prevent him from being approved for bariatric surgery, he challenged this risk and drank alcohol over Christmas, which led to weight gain. After bariatric surgery, his attitude to challenging continued as he adjusted:

They [the bariatric surgical multi‐disciplinary team] weren't very happy with me. They wanted me to lose more weight. I went back after 6 months and they said you should have lost more, a stone a month. I've lost weight, what more do you want? (Participant F)

Pre‐surgically, the Risk Challenger acknowledged he was obese and suffering from poor health but had opted for a gastric sleeve as he thought it would have a lesser impact on his life:

I said I wanted a sleeve as I thought I wouldn't have much of a life with a bypass. The way I understood it, it was just a tube, just bypassed the stomach and went straight down, but I wanted to be able to eat something…have a drink, so I didn't look into it because I just wanted the sleeve. (Participant F)

During the interview, the Risk Challenger stressed his desire to lead what he called a ‘normal life’, unconstrained by the effects of surgery. He therefore challenged the risk of not strictly adhering to post‐surgical advice, devising his own way of eating and drinking to allow him to feel ‘normal’:

I rarely have a cup of tea now. I used to drink it like it was going out of style….I don't know if I'm replacing the sugar hit now, but I drink more pop [carbonated drinks] than I did before and I still put sugar in my tea. I pick [graze], I used to pick all the time and still do, but now I pick sensibly. If I'd kept on drinking , eating and smoking I would have been dead by the time I was 50.I still do these things, but moderately. (Participant F)

It was noted that when Participant F had come for the interview, he was drinking a bottle of Coke®. Sugary and fizzy drinks are not recommended after surgery. After the interview had finished, he had lit up a cigarette; again, this is a habit that is actively discouraged by the bariatric multi‐disciplinary team (MDT). We noted this, not as not as a judgment, but thought the bottle of Coke® and the cigarette might be symbols which represented a ‘normal life’ for the Risk Challenge. Partaking in these activities may have given him a sense of normality, which was important for him in terms of his adjustment to post‐surgical life. He did not appear to be worried or struggling with any aspect of adjustment; his attitude was what was different from the other risk profiles, and this was also reflected.

I'm going to keep on riding my motorcycle, but hopefully be even healthier, but have a life. The surgery probably saved me from dying. (Participant F – Risk Challenger)

Reflecting back on the decision to have undergone bariatric surgery: The Three Risk Attitude Profiles

Despite difficulties adjusting to life after bariatric surgery, none of the participants in any of the risk attitude profiles regretted their decision to undergo the operation:

I have no regrets and I would encourage anyone to have it done, definitely. No matter what has gone on in my life, I would still encourage anyone to have it done, it changes your life (Participant D – Risk Contender)

Additionally, all participants unequivocally recommended bariatric surgery to others.

Go for it, without a doubt. I mean it depends what you what, it's not cosmetic surgery and you are in it for the long haul, but its life changing, it really is. My mind was made up before I went to the doctor, my arthritis, my mother who is obese, just massive, she's housebound, has diabetes, heart problems and I thought I don't want to be like that (Participant J – Risk Accepter)

Participants were shaped by similar, yet individual, experiences, but the way in which they interpreted the risks associated with the adjustment process was the differentiator. Demographic variables such as age, gender, employment and family status were diverse across the Risk Accepter and Risk Contender categories, which show that the attitude of risk applied across a range of participants. There was a mixture of types of bariatric surgical procedures in the Risk Accepter and Risk Contender categories, so we do not believe that the interpretation of risk was related to specific procedures. As only one Risk Challenger was identified, no comparisons could be made in this category. The time at which the participants were interviewed did not appear to influence risk interpretation as similar concepts and experiences were consistently found throughout the analysis for participants within their risk profiles. There were no issues identified that could be attributed to gender.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study sought to explore patients’ experiences of adjustment to life after bariatric surgery. We found that many participants were reluctant to discuss their experiences of surgery in social situations, sometimes even with close relatives, with frequent partial or non‐disclosure of the method of their weight loss (see Table 5). Within social environments, discussions surrounding bariatric surgery were reported to be a source of worry with regards to the potential risks of revealing having undergone bariatric surgery due to being judged by others. This has been reported elsewhere in relation to ‘good’ and ‘bad’ methods of weight loss 18, 27, although our data go further and suggest that this perspective may negatively affect the participants’ adjustment to life after surgery. The interpretation of risk, particularly towards fear of judgment after having being stigmatized for their previous obese state, can lead to selective or non‐disclosure of bariatric surgery. This social interpretation has not been reported previously and remains the preserve of those who have undergone bariatric surgery and the bariatric surgical teams and other healthcare professionals who work within the field.

Table 5.

Participant‐reported disclosure about undergoing bariatric surgery with others

| Participant | Disclose to family | Safe? | Disclose to friends | Safe? | Work and/or colleagues | Safe? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| B | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | No | No |

| C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| D | Select | Sometimes | No | No | No | No |

| E | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| G | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | Yes | Yes |

| H | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | N/A | N/A |

| I | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | N/A | N/A |

| J | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | Yes | Yes |

| K | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | N/A | N/A |

| L | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | Yes | Yes |

| M | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | N/A | N/A |

| N | Yes | Sometimes | Select | Sometimes | N/A | N/A |

| O | Yes | Sometimes | Select | Sometimes | Yes | Yes |

| P | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| Q | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| R | Yes | Yes | Select | Sometimes | Yes | Yes |

The three risk attitude profiles of Risk Accepters, Risk Challengers and Risk Contenders, which were constructed from the participant narratives in this thesis, show that attitudes towards risk appeared influenced by the social situations they encountered, many of which were felt to have occurred because of the effects of bariatric surgery. Risk is discussed by the participants in the context of attitudes towards social situations, and their meanings and actions will be explored and unpicked to gain a greater understanding of these situations. Such social risks are ‘discursively constructed in everyday life with reference to the mass media, individual experience and biography, local memory, moral convictions and personal judgments’ (28, p.60).

Compared with other weight‐loss methods such as diet and exercise, bariatric surgery produces rapid weight loss, resulting in a visibly changed appearance in a relatively short period of time. A bariatric surgical patient thus moves from an obese, stigmatized state to one who invites scrutiny. Stigmatized afflictions fall into two categories: ones that cannot be disguised or hidden as ‘discredited’ and ones that are less visible and enable people to appear ‘normal’ as ‘discreditable’ 29. The visibility of adult obesity places obesity as a discredited state, but bariatric surgery places the formerly obese into a discreditable state as the physical appearance has changed and the person has moved to a more socially accepted state of overweight or normal body weight. The discredited state of bariatric surgery leaves the person open to judgment from others, which differs from further stigmatization.

The participant‐reported accounts that underpinned the co‐constructed theory of this thesis was that bariatric surgery is a relatively unknown entity outside those who have undergone procedures and is closely associated with adult obesity, which is a stigmatized condition. Many participants felt or reported accounts of stigmatization from others. Stigmatization tends to be associated with conditions or afflictions that possess deep‐rooted socio‐cultural perceptions, such as mental illnesses 30 and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) 31 in addition to obesity. The stigma of obesity is rooted in the perceptions of negative attributes towards the affliction, such as laziness, being weak‐willed and out of control 32. For those who have undergone bariatric surgery, it is the rapid change from the obese body and rapid change in bodily appearance that warrants scrutiny and questions, which lead to issues with self‐disclosure to others.

Limitations

The inclusion and exclusion criteria we used for the recruitment of participants mean that the findings are based on the experiences of the participants only and may not be reflective of the whole bariatric surgery population. In order to meet NHS ethical approval requirements, patients with any identified active psychological condition and/or receiving psychological intervention were excluded. The high frequency of psychological conditions reported within the bariatric surgery patient population means that a significant number of patients could not be recruited into this study. We do not know whether their views may have differed from those patients that we spoke to.

Additionally, the findings systematically showed that many participants were fearful of judgment of their decision to undergo bariatric surgery. Despite the anonymization of participants in the study, it should be assumed that some bariatric surgical patients may have chosen not to participate for this reason.

This study focused on the first 2 years following bariatric surgery; findings are limited to this time frame and may not represent experiences beyond 2 years. As participants were only interviewed once, it is unknown if the risk attitude profiles may have the potential to change over time. Individual attitudes are based on subjective interpretations, and therefore, it is only ever possible to achieve a partial understanding of the phenomenon under investigation, owing to the ‘complex and contradictory ways in which people perceive and respond to the risks they face in the social contexts of day‐to‐day life’ (33, p.2).

The concept of risk has many strands and interpretations. This study examines risk from a social constructivist perspective, focusing on the symbolic and socio‐cultural aspects. The act of disclosing may arise after inquiry from others for reasons such as questioning a person's rapid weight loss, changed physical appearance or eating patterns.

What it means

The three risk attitude profiles of Risk Accepters, Risk Challengers and Risk Contenders, which were constructed from the participant narratives in this study, are congruent with Lupton's (2013) definition of the subjective interpretation of risk. Participant attitudes towards risk appeared to be influenced by the social situations they encountered, many of which were felt to have occurred because of the effects of bariatric surgery.

Implications for practice

Practitioners

The participant‐reported attitudes towards social risks are central to understanding the underlying meanings and actions that patients may undertake as part of this process. This information has implications for practice; it can be used by healthcare professions to generate discussions with patients to prepare them for surgery and support them afterwards by raising awareness of issues that they may encounter in social situations, discussing how other patients have dealt with these situations and how they might deal with a similar situation.

Patients

These findings may be used for both pre‐ and post‐bariatric surgical patients. When discussing their post‐surgical experiences, many of the participants in this study stated they wished they had known more about other peoples’ experiences prior to surgery in order to prepare them for life afterwards. Additionally, many of the participants wanted to know how their experiences of adjusting to life after bariatric surgery compared to the other participants and had asked to have copies of the findings. These findings could be raised with individual patients or in a patient support group to facilitate discussion and encourage others to share concerns pre‐surgically and to give post‐surgical patients insight into others’ experiences, which may provide reassurance and support through the comparison of their experiences with others. Patients should be made aware that, at present, the changes in their physical capacity to eat may alter social interactions, and they may experience scrutiny from others as a result, which might be uncomfortable. People who may not wish to disclose having undergone bariatric surgery to others should be encouraged to think about how they would deal with social situations that, based on others’ experiences, may be encountered. To aid support given by healthcare professionals, patients should be encouraged to engage with others who have undergone bariatric surgery, such as participating in face‐to‐face patient support groups and other sources of social support, e.g. social media, to learn how others deal with social encounters.

Recommendations for future research

More research into patient experiences of bariatric surgery in social contexts would help develop the limited research in this area, which is needed given the increasing number of people with obesity and metabolic disease who seek bariatric surgery as a result of changing eligibility. The co‐constructed theory suggests a participant‐reported lack of knowledge in others, particularly the lay public, of the social experiences of adjusting to bariatric surgery. It is also important to examine the negative societal attitudes, where these exist, towards judgement about bariatric surgery, with a view to challenge mindsets through the understanding of how this information is being interpreted.

Conflict of Interest Statement

YG is a reviewer for Clinical Obesity. KM is on the editorial board of Clinical Obesity. Researchers JL, PKS and CH have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

YG conceived the idea for the paper and carried out data collection and analysis. JL, PKS, CH and KM assisted with the data analysis. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions. The authors acknowledge the support of The Biosocial Society, which provided a grant for the costs of fieldwork associated with this study.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 27 December 2017 after original online publication

References

- 1. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013; 273: 219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Obesity: Identification, Assessment and Management Department of Health, 2014. [PubMed]

- 3. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17: 941–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sogg S, Gorman M. Interpersonal changes and challenges after weight‐loss surgery. Prim Psychiatry 2008; 15: 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robson C. Real World Research, 3rd edn. John Wiley: Chichester, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bocchieri L, Meana M, Fisher B. Perceived psychosocial outcomes of gastric bypass surgery: a qualitative study. Obes Surg 2002; 12: 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Throsby K. Happy re‐birthday: weight loss surgery and the 'new me'. Body Soc 2008; 14: 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryan MA. My story: a personal perspective on bariatric surgery. Crit Care Nurs Q 2005; 28: 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earvolino‐Ramirez M. Living with bariatric surgery: totally different but still evolving. Bariatr Nurs Surg Patient Care 2008; 3: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magdaleno R Jr, Chaim E, Pareja J et al. The psychology of bariatric patient: what replaces obesity? A qualitative research with Brazilian women. Obes Surg 2011; 21: 336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Groven KS, Engelsrud G, Råheim M. Living with bodily changes after weight loss surgery: women's experiences of food and dumping. Phenomenol Pract 2012; 6: 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zunker C, Karr T, Saunders R et al. Eating behaviors post‐bariatric surgery: a qualitative study of grazing. Obes Surg 2012; 22: 1225–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogden J, Clementi C, Aylwin S. The impact of obesity surgery and the paradox of control: a qualitative study. Psychol Health 2006; 21: 273–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wysoker A. The lived experience of choosing bariatric surgery to lose weight. J Am Psychiatric Nurses Assoc 2005; 11: 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Engstrom M, Forsberg A. Wishing for deburdening through a sustainable control after bariatric surgery. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐being 2011; 6: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogden J, Avenell S, Ellis G. Negotiating control: patients' experiences of unsuccessful weight‐loss surgery. Psychol Health 2011; 26: 949–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Groven KS, Råheim M, Engelsrud G. "My quality of life is worse compared to my earlier life". Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐being 2010; 5: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drew P. But then I learned … weight loss surgery patients negotiate surgery discourses. Soc Sci Med 2011; 73: 1230–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silverman D. Interpreting Qualitative Data, 5th edn. Sage: London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bryant A, Charmaz K. (eds). The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. Sage: London, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Birks M, Mills J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide. Sage: London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Sage: London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graham Y, Small PK, Hayes C, Wilkes S et al An exploration of patient experiences of adjusting to life in the first two years after bariatric surgery (thesis). University of Sunderland: Sunderland, 2016.

- 24. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd edn. Sage: London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stern PN. Grounded theory methodology: its uses and processes. Image 1980; 12: 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lupton D. Risk and emotion: towards an alternative theoretical perspective. Health Risk Soc 2013; 15: 634–647. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williamson JML, Rink JA, Hewin DH. The portrayal of bariatric surgery in the UK print media. Obes Surg 2012; 22: 1690–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zinn J, Taylor‐Gooby P. (eds). The Challenge of (Managing) New Risks. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Penguin: London, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G et al. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182: 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fordham G. HIV/AIDS and the Social Consequences of Untamed Biomedicine. Routledge: London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Psychosocial origins of obesity stigma: toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obes Rev 2003; 4: 213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilkinson I. Social theories of risk perception: at once indispensible and insufficient. Curr Sociol 2001; 49: 1–22. [Google Scholar]