To the Editor

Peripheral T‐cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of mature, post‐thymic, T‐ and natural killer‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL)—nearly all subtypes are associated with a poor prognosis.1, 2 Regardless of subtype, patients with PTCL typically receive induction chemotherapy (commonly CHOP [cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine + prednisone]) as first‐line treatment.3, 4, 5 Except for anaplastic lymphoma kinase–positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma, outcomes are generally poor and many responding patients rapidly relapse.1, 2, 3, 4 Achievement of durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL is difficult, and there are few treatment options.2, 3, 4

Angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma (AITL) is a common subtype of PTCL (16% of diagnoses in the USA, 18% in Asia and 29% in Europe).3 The 5‐year overall survival (OS) in patients with AITL is reported to be just 32%,3 and AITL is characterised by generalised lymphadenopathy, extranodal involvement, hypergammaglobulinemia, and advanced stage at presentation.6, 7 Immune dysregulation commonly results in infections, which are a frequent cause of death in patients with AITL.6

Romidepsin is a structurally unique, potent, bicyclic class I selective histone deacetylase inhibitor approved for the treatment of all subtypes of relapsed/refractory PTCL.8, 9, 10, 11 In the pivotal phase 2 trial conducted in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL, romidepsin treatment resulted in durable responses with manageable toxicity.12, 13 The objective response rate (ORR) was 25% (33/130), including 15% confirmed/unconfirmed complete responses (CR/CRu),12, 13 and the median duration of response (DOR) was 28 months.13 Patient baseline characteristics (including PTCL subtype) or prior treatments did not significantly affect response rates.12, 13 The most frequent romidepsin‐related adverse events (AEs) were gastrointestinal and asthenic conditions, which were primarily grade 1/2 and rarely resulted in drug discontinuation.12

Here, we report updated data from the pivotal phase 2 study focused on patients with AITL. In the overall study, eligible patients had PTCL (measurable disease by International Working Group [IWG] criteria 14 and/or measurable cutaneous disease) relapsed/refractory to ≥1 therapy, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of zero to two and adequate bone marrow and organ function at enrollment. Patients with significant cardiac abnormalities were excluded, and concomitant use of drugs that could significantly prolong the QTc interval was not allowed. Patients with hypokalemia and/or hypomagnesemia (which are associated with electrocardiogram abnormalities) 15 were to be supplemented before romidepsin dosing. Additional details for this open‐label, single‐arm, phase 2 study have been previously described.12

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation. Patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The protocol, informed consent form, and any other relevant study documentation were approved by the appropriate institutional review board for each participating institution.

Patients received romidepsin as a 4‐h intravenous infusion at 14 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 of 28‐day cycles (approved dosing in both PTCL and cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma) 11 for up to six cycles. Patients with stable disease or response could continue beyond six cycles at the discretion of the patient and investigator. Due to extended treatment in some patients, the protocol was amended to allow for (but not mandate) maintenance dosing of romidepsin: two doses per cycle in patients treated for ≥12 cycles and one dose per cycle in patients who received two doses per cycle for ≥6 cycles through at least cycle 24.

Response was assessed every two cycles by both investigators and an independent review committee (IRC; expert radiologists and hematologic oncologists) according to the 1999 IWG guidelines for NHL (IWG‐NHL).14 All descriptive statistical analyses were performed by using SAS statistical software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Time‐to‐event data were summarised by Kaplan–Meier methods.

Of 131 total patients in the overall study, 27 were diagnosed with AITL. Largely, the baseline characteristics of the 27 patients with AITL (Table 1) were similar to those of the overall study population, which were previously reported.12 Patients with AITL had higher‐stage disease; only 4% of patients with AITL versus 29% of patients overall had stage I or II disease.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

| Patients with AITL (n = 27) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (range) | 62 (47–76) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 15 (56) |

| Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 5 (19) |

| 1 | 17 (63) |

| 2 | 5 (19) |

| International prognostic index at study baseline, n (%) | |

| <2 | 4 (15) |

| ≥2 | 23 (85) |

| Time since diagnosis in years, median (range) | 1.3 (0.4–6.4) |

| Stage at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| I | 0 |

| II | 1 (4) |

| III | 13 (48) |

| IV | 13 (48) |

| Type of prior systemic therapy, n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 27 (100) |

| Monoclonal antibody therapy | 7 (26) |

| Other immunotherapy | 4 (15) |

| Autologous stem cell transplant | 2 (7) |

| Radiation therapy | 3 (11) |

| Prior systemic therapies, median (range) | 2 (1–8) |

| 1, n (%) | 9 (33) |

| 2, n (%) | 10 (37) |

| 3–4, n (%) | 4 (15) |

| >4, n (%) | 4 (15) |

| Refractory to most recent therapy, n (%)a | 10 (37) |

| Disease in bone marrow at baseline, n (%) | 12 (44) |

| Elevated lactate dehydrogenase, n (%) | 14 (52) |

CHOEP, CHOP + etoposide; ICE, ifosfamide + carboplatin + etoposide; MADEC, cytarabine + etoposide + cyclophosphamide + methotrexate + dexamethasone.

Refractory to CHOP (n = 2), CHOEP (n = 1), ICE (n = 3), GVD (n = 1), MADEC (n = 1), pralatrexate (n = 1), and alemtuzumab (n = 1).

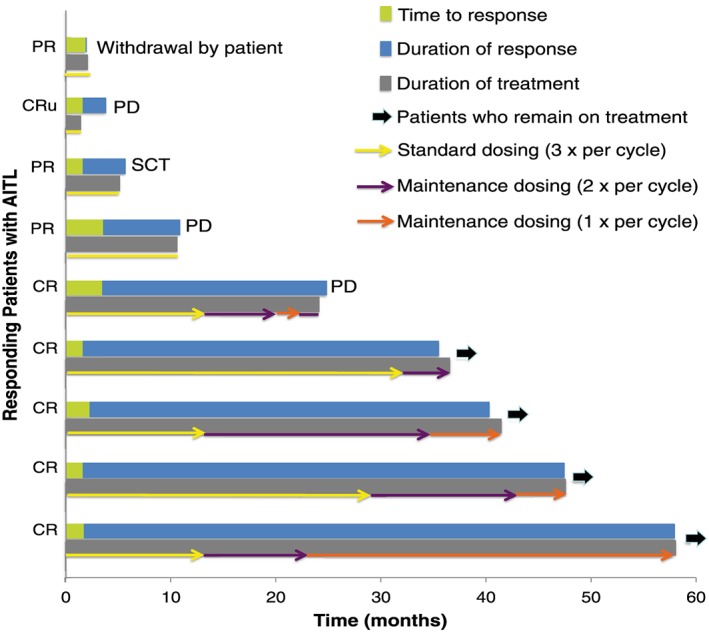

The ORR for patients with AITL treated with romidepsin was 33% (9/27); six of nine responders achieved CR/CRu. Ten patients with AITL were refractory to their last prior therapy, five of whom achieved an objective response (50%) to romidepsin, including four with CR/CRu (40%). Responders were refractory to CHOP, GVD (gemcitabine + vinorelbine + doxorubicin), pralatrexate, or alemtuzumab. Of the nine responding patients with AITL, five achieved a long‐term response (≥12 months; Figure 1). Of these five patients, two had received one prior therapy, and three had received two prior therapies. All five received maintenance dosing of romidepsin. The timing of initiation of maintenance dosing varied because of investigator discretion and the time of protocol amendment initiation that allowed maintenance dosing. Four of five patients with AITL who began maintenance dosing continued in CR at the time of data cut‐off (30 September 2012).

Figure 1.

Response kinetics of patients by dose. PR, partial response; SCT, stem cell transplant.

Similar to the overall study population,12 most responding patients with AITL were in response at the time of first assessment (cycle 2), with a median time to response of 52 (range, 50–107) days; median DOR was not reached (range, <1–56+ months).

The AE profile for patients with AITL was consistent with the known profile for romidepsin in patients with all subtypes of PTCL.11, 12, 13 The most common grade ≥3 AEs were thrombocytopenia (30%, all drug‐related), neutropenia (22%, all drug‐related), infections (all types pooled; 22%, 4% drug‐related) and anemia (15%, 7% drug‐related). Fifteen patients (56%) experienced serious AEs; nine (33%) of which were drug related. Infections (all types pooled) were the most common serious AE (n = 7, 26%), but no infection led to discontinuation. Overall, six patients (22%) discontinued due to AEs, including five (19%) for drug‐related AEs. Doses were held or reduced because of AEs in 12 (44%) and five (19%) patients, respectively, including nine (33%) and five (19%) patients because of drug‐related AEs. Thrombocytopenia was the most common AE leading to doses held or reduced in six (22%) and two (7%) patients, respectively, and the only AE that led to discontinuation in >1 patient (n = 2).

In conclusion, romidepsin induced rapid, complete, and durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory AITL, including those refractory to their last treatment. Patients with long‐term responses to romidepsin received maintenance dosing, although the optimal time to initiate reduced dosing is unknown. The AE profile for romidepsin in patients with AITL was consistent with the known profile in patients with PTCL; infections were generally not drug related and did not lead to discontinuations. These results provide additional support for the use of romidepsin in relapsed/refractory AITL. Further study of responding patients, particularly in light of discoveries of frequent DNMT3A, TET2, IDH2, and RhoA mutations in AITL,16, 17 may lead to biomarkers for sensitivity to HDACi.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

- BP –

Honoraria: Celgene Corporation.

- SMH –

Research: Celgene Corporation, Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc, Infinity, Kiowa‐Kirin, Seattle Genetics, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Consulting and Honoraria: Amgen, Inc, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Celgene Corporation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

- HMP –

Research Funding, Honoraria, Consulting: Celgene Corporation.

- FMF –

Advisory board, speaker, honoraria: Celgene Corporation; advisory board, investigator, honoraria: Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and Infinity Pharmaceuticals; advisory board, principal investigator, speaker, honoraria; Seattle Genetics.

- LS –

Consulting and Honoraria: Celgene Corporation and Spectrum Pharmaceuticals.

- MG, DC, MW –

Have nothing to disclose.

- FM –

Honoraria: Genentech, Mundipharma, Bayer, Spectrum, Gilead.

- SPI –

Employee: Houston Methodist Cancer Center; honoraria: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; speaker bureau: Celgene Corporation.

- ARS –

Consultancy, and honoraria: Celgene Corporation, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals.

- BEB & JW –

Consulting and Financial Pay for Review of Article: Celgene Corporation.

- BC –

Consulting: Celgene Corporation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors take full responsibility for the content of this manuscript but thank William Ho, PhD (MediTech Media), for providing medical editorial assistance. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Celgene Corporation.

Pro B, Horwitz SM, Prince HM, et al. Romidepsin induces durable responses in patients with relapsed or refractory angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma. Hematological Oncology. 2017;35:914–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2320

REFERENCES

- 1. Foss FM, Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Gascoyne RD, Rosen ST, Tobinai K. Peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:6756–6767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horwitz SM. Management of peripheral T‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D, International T‐Cell Lymphoma Project . International peripheral T‐cell and natural killer/T‐cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4124–4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma. V.3.2016.

- 5. Foss FM, Carson KR, Pinter‐Brown L, et al. Comprehensive oncology measures for peripheral T‐cell lymphoma treatment (COMPLETE): First detailed report of primary treatment. Blood. 2012;120: [abstract 1614] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mosalpuria K, Bociek RG, Vose JM. Angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma management. Semin Hematol. 2014;51:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alizadeh AA, Advani RH. Evaluation and management of angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma: a review of current approaches and future strategies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2008;6:899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tan J, Cang S, Ma Y, Petrillo RL, Liu D. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical trials as anti‐cancer agents. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradner JE, West N, Grachan ML, et al. Chemical phylogenetics of histone deacetylases. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ISTODAX (romidepsin) [package insert]. 2014.

- 12. Coiffier B, Pro B, Prince HM, et al. Results From a Pivotal, Open‐Label, Phase II Study of Romidepsin in Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T‐Cell Lymphoma After Prior Systemic Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coiffier B, Pro B, Prince HM, et al. Romidepsin for the treatment of relapsed/refractory peripheral T‐cell lymphoma: pivotal study update demonstrates durable responses. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El‐Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiol J. 2011;18:233–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T‐cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123:1293–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sakata‐Yanagimoto M, Enami T, Yoshida K, et al. Somatic RHOA mutation in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]