Abstract

For decades, Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) and Sjögren’s syndrome-like (SS-like) disease in patients and mouse models, respectively, have been intensely investigated in attempts to identify the underlying etiologies, the path-ophysiological changes defining disease phenotypes, the nature of the autoimmune responses, and the propensity for developing B cell lymphomas. An emerging question is whether the generation of a multitude of mouse models and the data obtained from their studies is actually important to the understanding of the human disease and potential interventional therapies. In this brief report, we comment on how and why mouse models can stimulate interest in specific lines of research that apparently parallel aspects of human SS. Focusing on two mouse models, NOD and B6·Il14α, we present the possible relevance of mouse models to human SS, highlighting a few selected disease-associated biological processes that have baffled both SS and SS-like investigations for decades.

Keywords: Sjögren’s syndrome, Mouse models, Interferon signature, Signal transduction pathways, B cell lymphomagenesis

1. Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a progressive complex heterogeneous rheumatoid autoimmune disease, most frequently diagnosed in post-menopausal women. It is characterized by loss of salivary and/or lacrimal gland functions, occurring in isolation or as a secondary phenomenon with other autoimmune diseases, e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, primary biliary cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease [1,2]. In some patients, disease remains restricted to the salivary and/or lacrimal glands. In many patients, however, systemic involvement results in pathology of multiple organs and tissues, including the lungs, kidneys and the peripheral nervous system, quite possibly from systemic vasculitis [3]. Additional features defining SS include the presence of tissue-specific autoantibodies, anti-nuclear autoantibodies (ANAs), detectable Rheumatoid Factor (RF) [4–6], a strong interferon (IFN) signature thought to be the basis for patient complaints of chronic fatigue [7–10], oral and ocular microbial diseases, and a relatively high incidence of associated lymphomas, especially non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphomas [11,12]. This presence of autoantibodies and the demonstration of B lymphocytes and occasional germinal centers in the salivary and lacrimal glands, together with the high frequency of B cell lymphomagenesis, indicate the importance of B cells in the pathophysiology of SS. Nevertheless, it is critical to remain cognizant of the pathogenic CD4+ T cell populations and loss of T cell regulation [13] that influences B cell responses.

Despite years of efforts to define the genetic, environmental and immunological bases for development of SS, the underlying etiology remains poorly understood, even though its interferon (IFN)-signature and pathogen recognition receptor (PRR) profiles suggest a viral involvement [9,14]. Furthermore, the inability to identify SS in the early stages of disease onset stymies studies designed to investigate those covert events leading to the overt clinical disease seen in patients. As a result, to study the pathophysiological and immunological nature of this autoimmune disease, numerous mouse models have been developed that presumably mimic specific characteristics common to the human disease. The potential relevance of these mouse lines, along with the genetic bases for their disease phenotypes, are discussed in detail in several recent reviews [15,16]. Nevertheless, there remain serious concerns that these SS-like models are often artificial, exhibit at best only partial disease, and do not sufficiently represent the clinical human disease. Furthermore, most models have not been extensively studied beyond their disease phenotype. As a result, many investigators consider mouse models inappropriate for preclinical and translational studies, even if these models permit investigations into elements of the pathobiology and molecular processes possibly important in establishing disease but still covert in patients commonly diagnosed in late stage disease.

2. SS-like disease in mouse models

The relationship between SS and SS-like disease remains tentative, yet studies over the past several decades using mouse models exhibiting SS-like disease have clearly highlighted selected disease-associated biological phenomena, biological processes and even molecular events seemingly identical or at least similar to human SS disease. A few examples of similarities between SS-like disease in mouse models to human SS is presented in Table 1. Irrespective, the etiology of SS-like disease must be, to a large extent, associated with the specific genetic makeup of the individual mouse model and coupled to an immunological response triggered by an environmental event. In a comprehensive review, Delaleu et al. [17] classified inbred lines of mice reported to develop manifestations of SS-like disease into three general groups based on either genotypic or phenotypic features: (a) extrinsic factor-induced models, (b) transgenic (TG) models, and (c) spontaneous disease models. Each group offers unique views of SS/SS-like disease.

Table 1.

Comparison of Sjögren’s Syndrome phenotypes in humans and mouse models.

| Sjögren’s syndrome disease phenotype | SS patients | Aec1Aec2 | B6·IL14α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dacryoadenitis/Meibomian gland disease | (Yes) Yes | Yes/(Yes) | Yes/(?) |

| Sialadenitis | Yes | Yes | |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokine production | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Autoantibodies & Rheumatoid Factor | |||

| Anti-Ro/SS-A, Anti-La/SS-B, Anti-DNA (ANAs) | Yes | Variable | Variable |

| Anti-α-fodrin, Anti-β-adrenergic receptor | |||

| Anti-type-3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor | |||

| Decreased tear flow rates | Yes | Variable | Yes |

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) | Yes | Variable | |

| Ocular epithelium dessication | Yes | Yes | |

| Decreased Break-up time | Yes | (?) | |

| Altered proteins in tears | (Yes) | Yes | |

| Decreased Lysozyme & Lactoferrin activity | Yes | (?) | |

| Decreased saliva flow rates | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stomatitis sicca | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Altered proteins in saliva | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Decreased Amylase & EGF activity | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lymphomagenesis | Yes | No | Yes |

2.1. Extrinsic factor-induced models

Extrinsic factor-induced experimental models exhibiting a SS-like pathology require exogenous administration of an extrinsic factor, such as proteins or viruses. The overall goal is to break immunological tolerance to specific organ or tissue antigens suspected of having a role in the disease that subsequently leads to activation of an immune system-initiated pathogenesis. The major drawback to these models is our relatively limited knowledge about disease-relevant auto-antigens in SS, thus the selected extrinsic factor is often of personal bias. Currently, four such models have been generated: BALB/c mice immunized with 60-kDa Ro peptides or New Zealand Mixed (NZM) 2758 mice immunized with Ro-60 or Ro52 antigen [18,19], C57BL/6-M3r−/−mice vaccinated with muscarinic acetylcholine type-3 (M3R) receptor peptides [20], PL/J mice immunized with carbonic anhydrase-II (CA-II) peptides [21], and C57BL/6 mice intra-peritoneally injected with murine cytomegalovirus [22]. The first three models are based on the fact that SS patients generate autoantibodies to these three tissue proteins, while the latter model is based on the concept that a virus may be an underlying cause of SS. Although studies using such immunization protocols indicate that the induction of antibodies to self-peptides and self-proteins or inflammatory responses to viruses are capable of inducing manifestations observed in SS, they provide limited information about the development or onset of disease, even if they generally support the concept that Ro, M3R, CA-II and viruses are antigens that can induce, at least, a partial SS-like pathology.

2.2. Transgenic (TG) mouse models

Silencing or over-expressing specific genes in animal models has become an efficient means to identify globally the biological pathways affected downstream following disruption of a particular gene function suspected of having a role in SS pathology. To date, modified genes include selected cytokines, growth factors, regulators of immunity or development, and hormone-associated proteins. Genetic modifications in both knock-out and knock-in TG mice have been used to identify how phenotypic changes result in development and onset of SS-like pathology related to a variety of different phenomena of SS-like disease. While genes generally selected for modification are associated with regulating immune responses (e.g., interleukins), governing developmental processes (e.g., growth factors), or contributing to exocrine gland homeostasis (e.g., estrogen balance), data from these mouse models tend to identify potentially critical molecular processes leading to glandular infiltration by leukocytes and subsequent dysfunction. Unfortunately, few studies of these various mouse strains have proceeded beyond the observational stage to define specific biological and molecular processes possibly involved in the observed changes associated with glandular homeostasis and function.

2.3. Spontaneous disease models

In general, the earliest mouse models of SS were inbred strains that exhibited SS-like disease manifestations spontaneously, e.g., NZB/NZW and Non-obese diabetic (NOD), two lines originally used to study lupus and diabetes, respectively [23,24]. While no one inbred mouse line should be expected to fully mimic all relevant phenotypes of SS disease, these spontaneous models, taken as a group, exhibit much of the heterogeneity seen in the complex genetics, diverse disease phenotypes, underlying pathology, and clinical manifestations present in patients with SS. A potential explanation for such a phenomenon might be related to the lack of genetic diversity in the common laboratory mouse, combined with the probability that SS can develop from multiple aggregated molecular and biological dysfunctions. Nevertheless, model organisms that do develop a SS-like disease spontaneously might better represent the assumed multi-factorial etiology and complex pathogenesis of SS compared to mice with a single genetic manipulation. Since inbred strains are commonly used for research purposes, the conclusions drawn from such experimental studies may translate well to specific subpopulations of SS patients while being only partly valid or even totally invalid for other groups of SS patients. This fact must be considered in clinical trials where therapeutic significance must be achieved with an intervention arising from studies in an inbred model, but a patient population with diverse disease phenotypes.

3. What have we learned about SS from mouse models of SS-like disease?

While a significant number of different mouse models have been developed that present with various immune-pathophysiological characteristics observed in SS disease, for most models there are limited data on how studies in these models may provide relevant information for the human disease, especially when considering the diversity and complexity of disease phenotypes in SS patients. Alternatively, one might argue that these mouse models, as a whole, actually represent the full phenotypic diversity, thereby supporting the concept that multiple and distinct biological processes can result in determining the various characteristics and manifestations exhibited within this syndrome. For example, NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, two strains that naturally develop, respectively, secondary and primary SS-like diseases closely characteristic of human SS, rarely develop lymphomas, yet C57BL/6-IL14α+ (B6·IL14α) and C57BL/6-Baff+ (B6·Baff) transgenic (TG) mice that exhibit SS-like clinical disease also transition to a state of B cell lymphomagenesis on aging [25,26]. Thus, this set of mice mimics the situation in humans wherein subgroups of SS patients will either remain lymphoma-free or develop B cell lymphomas.

A second interesting comparison between SS and SS-like disease deals with the leukocyte infiltrations of specifically targeted exocrine glands and tissues. Similar to the human disease, NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice not only show a progressive T and B cell infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands, but also the lungs [24,27–29]. In addition, antibody depositions are prevalent in the kidneys, indicative of glomerulonephritis [30]. Perhaps even more interesting is the observation, first made in C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, then soon after in humans [31], indicating the presence of IL-17-producing CD4+ TH17 cells in the salivary glands of both species diagnosed with SS/SS-like disease. Since then, an increasing number of mouse models of SS-like disease are reporting the presence of TH17 cells in the glands [32,33], which may prove pivotal in SS following the recent publications of Nguyen et al. [34,35] suggesting differential responses of cells in male versus female C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice and human SS patients to IL-17. This observation, combined with the detection of reduced IL-2 production, first described in NOD mice [36], have focused attention on the importance of the innate inflammatory response in both murine and human SS diseases that now must be analyzed fully and defined molecularly.

A third important comparison between SS and SS-like disease involves the production of autoantibodies, especially anti-SS-A (Ro), anti-SS-B (La) and anti-M3R. NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice produce high levels of anti-nuclear autoantibodies (ANAs), anti-Ro and/or anti-La autoantibodies [37]. NOD and its recombinant inbred (RI) mice were shown to naturally produce anti-M3R autoantibodies [38], a finding that, with the observation that SS patients also produce anti-M3R autoantibodies [39–41], points to the possibility that antibody inhibiting the binding of acetylcholine to its muscarinic acetylcholine receptor is responsible, in part, for loss of stimulated glandular secretions. On the other hand, both C57BL/6-Act1−/− (Adaptor molecule Act1-deficient) and C57BL/6-RbAp48+/+ (Retinoblastoma-associated protein 48 enhanced) TG mice naturally produce anti-Ro and anti-La autoantibodies during their development and onset of a SS-like disease, but there are no reports indicating these strains produce anti-M3R auto-antibodies [42,43].

While these examples demonstrate a few of the major similarities between SS in humans and SS-like disease across several inbred mouse lines, it is important to reiterate that one should not expect a single inbred mouse model to exhibit all the characteristics observable in the human disease, especially considering the multiple phenotypes reported in SS patients wherein many exhibit only a few of the diagnostic markers, as well. Furthermore, it should also be anticipated that at a molecular level the two species might carry out a common physiologic or biological event using dissimilar gene sets making direct comparisons difficult to identify. Nevertheless, mouse models are permitting investigations into the early covert disease stages not generally accessible in SS patients. Thus, one must balance the advantages versus the disadvantages, as well as the specific goals of any study, when selecting a mouse model to study SS. In this regard, our group at the University of Florida has focused almost exclusively on the NOD mouse, a naturally-occurring model of secondary SS, the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse, a NOD congenic mouse line with a naturally-occurring primary SS, and the large set of RI mice derived from these two models. These mouse lines have provided insight into a wide range of potentially important factors for development and onset of SS pathology.

3.1. The NOD mouse

The NOD inbred line was derived from cataract-prone and outbred Jcl/ICR mice, but popularized due to its propensity to develop type 1 diabetes (T1D), even though these mice exhibited signs of both thyroiditis and SS-like disease, as well. Early studies of autoimmunity in the NOD mouse revealed that T1D was fully dependent on the expression of the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHCII) haplotype H-2g7 [44], whereas SS-like disease remained intact in RI mice like NOD.B10-H2b RI expressing a MHCII H-2b haplotype while being resistant to the onset of overt T1D [45]. Although some genetic susceptibility elements related to T1D also contribute to SS-like disease, it is clear that these two pathologies develop independently of each other [27,45,46] and, at the same time, indicate that SS-like disease has a weak association with specific MHC haplotypes, similar to human SS. Nevertheless, auto-immune manifestations in NOD mice result from a complex pathology involving genetics, sensitivity to exogenous factors, and apparent defects in central and peripheral tolerance [44], while combinations of these factors appear to define the propensity for developing autoimmune thyroiditis [47], systemic lupus erythematosus [48], and myasthenia gravis [49] along with T1D and SS-like diseases.

3.2. The C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse

Development of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse line was carried out to circumvent a host of extraneous problems associated with its parental NOD strain. These include (a) the potential impact of T1D on the physiological processes of saliva and tear secretion, (b) the probable interference of T1D on both overt and asymptomatic biological readouts in examining the underlying pathophysiological, biological and/or immunological pathology, (c) the inconsistent penetrance of diabetes in offspring, (d) the random requirement for insulin treatment, (e) the lack of a comparative non-disease control strain, and (f) the presence of a multitude of immune system-associated defects [44]. Construction of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse involved identification of two genetic regions (Aec1 and Aec2) in the NOD mouse that not only showed synteny with genetic regions associated with SS, but proved necessary and sufficient to transfer SS-like disease to the non-autoimmune C57BL/6J mouse [27,28]. The C57BL/6J mouse was selected as the genetic background recipient strain, in part, because of the high number of single gene knock-out and knock-in transgenic mice being created in C57BL/6J mice making it possible to observe how individual genes alter the SS-like disease phenotype, even though this approach is totally artificial in comparison to the human disease.

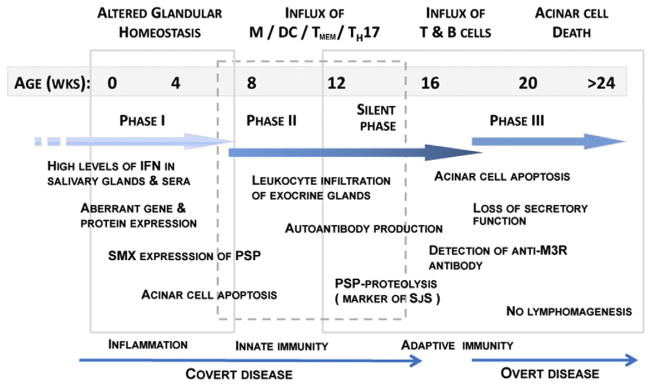

Studies using NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice have provided a detailed picture of the SS-like pathology and biological markers as it progresses through initiation of early inflammation to fill-blown clinical autoimmunity (Fig. 1). In addition, this graphic of the temporal development and onset of disease identifies involvement of multiple biological processes from altered physiology to cellular apoptosis, each requiring further investigations into the molecular basis to determine their individual roles in influencing pathological events and how the outcome of these events provides a SS-like disease phenotype of considerable similarity to the basic phenotype used to diagnose human SS. Furthermore, the C57BL/6.NOD- Aec1Aec2 mouse also identifies two restricted genetic regions in which genes responsible for disease reside. Nevertheless, genes of C57BL/6 mice residing outside of the Aec1 and Aec2 regions contribute significantly to the SS-like disease in C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice [50]. For example, during the inflammatory and innate phases (correlating with the pre-clinical disease stage), there were no increases in the percent of genes up-regulated residing in the Aec1 and Aec2 genetic regions over genes not residing in these genetic regions, whereas in the autoimmune phase (correlating with overt clinical disease) the percent of genes in Aec1 and Aec2 up-regulated were significantly increased over genes residing outside these susceptibility regions [27,28, 38]. Thus, discrimination between disease-causing and disease-promoting genes becomes difficult to discriminate.

Fig. 1.

Developmental stages of SS-like disease in NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice. Temporal changes in the pathophysiological and immunological events from birth to full onset of clinical disease are shown for NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, models of secondary and primary Sjögren’s Syndrome, respectively. Phases I, II and III are demarcated based on the ability to stop disease progression using recombinant inbred strains carrying specific dysfunctional genes essential for disease onset.

4. Can molecular processes identified in SS-like disease explain SS autoimmunity?

Over the course of intense investigations involving the pathophysiology and autoimmunity of human SS and mouse SS-like diseases, a number of biological processes have been uncovered that are of utmost scientific interest. Examples include: (a) the identification of strong INF-signatures and activations of endosomal-associated pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) indicative of a chronic viral infection during time of disease development, (b) dysregulation of the suppressors of cytokine synthesis (SOCS) pathways leading to failure in SOCS activations that normally control (auto)-immunity, (c) dysfunction in IL-2 resulting in reductions of T lymphocyte regulatory (TREG) cells, thus permitting persistent auto-reactive T cell activations, (d) persistent high levels of transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) affecting the TGFβ-Myc axis known to promote autoimmunity, and (e) over-expression of IL14α that promotes B cell lymphomagenesis.

4.1. The importance of an IFN-signature

Previous studies by Cha et al. [51,52] reported that high-levels of Ifnγ are detected in NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice as early as time of birth. When these SS-susceptible mice expressed either a nonfunctional Ifnγ (Ifng) or Ifnγ-receptor (Ifngr) gene, they subsequently failed to develop any aspect of SS-like disease, revealing an absolute requirement for Ifnγ in development and onset of disease. Originally, these data were interpreted as indicating an autonomous cellular response, but more recently, we believe the Ifnγ is vertically transmitted from mothers to offspring. Nevertheless, how and why Ifnγ plays such an important role in promoting disease in these mice remain quite speculative. More recently, follow-up studies have analyzed temporal gene expressions for both salivary and lacrimal glands isolated from C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice to identify interferon responsive/stimulated genes (IRGs/ISGs) [53]. Analyses revealed that of the nearly 1500 genes in the “interferome”, genes within each IRG/ISG sub-family exhibiting differentially regulated expressions were highly restricted in C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice [53,54]. A second observation is the fact that the majority of genes upregulated exhibited optimal expressions during the early disease phase.

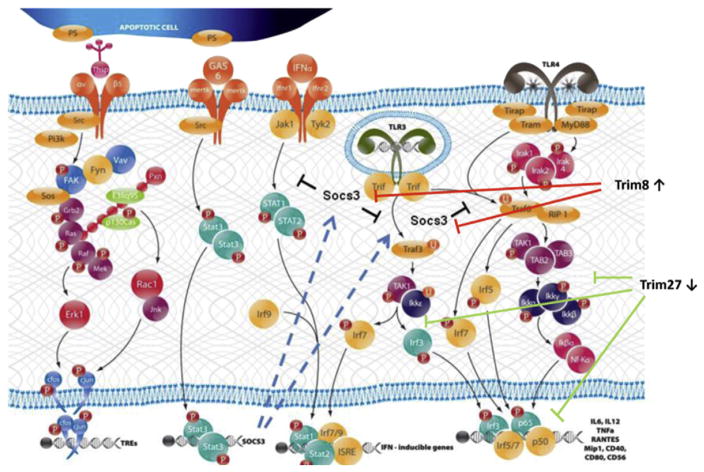

Multiple lines of evidence, especially from analyses of temporal global transcriptome data collected during development and onset of SS-like disease in the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse, point to the distinct probability that the IFN-signature defines a dsRNA viral etiology (Fig. 2). These include: (a) a concomitant up-regulated expression of Tlr3 and Tlr4, two genes encoding pathogen recognition receptors (PPRs) that signal through Traf3 via Trif and/or through Traf6 via a Trif-Trim23 complex to activate NF-κβ and Irf3/Irf7 transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFN, (b) the up-regulation of Ifih1, encoding Mda-5, with a concomitant down-regulation of Ddx58, encoding Rig-1, (c) the up-regulation of the interferon-responsive factors Irf3, Irf7, Irf8 and Irf9 critical for transcription of IFN and a variety of IRG genes expressed downstream, and (d) the down-regulation of Trim27, Trim30 and Trim40 with concomitant up-regulation of Trim8, Trim21 (encoding Ro52), Trim25 and Trim56, whose proteins impact viral replication and regulate expression of innate immunity.

Fig. 2.

Pathways activated during the early stage of SS-like disease in NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice. During the early stages of SS-like disease in NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, genes identifying at least two pathways involved in apoptotic cell recognition (e.g., αvβ5 and Mertk) plus three PRR pathways involved in double-stranded DNA viruses (TLR3, TLR4 and MDA5) are activated. Concomitantly, Trim molecules, members of the E3 ubiquitin ligase protein family and can function as regulators of the PRR pathways (as illustrated by Trim8 and Trim27). Trim8, which regulates expression of Socs3, together with Trim27, which regulates the TLR signaling pathways, indicate a strong up-regulated TLR signaling and interferon synthesis.

The three PRRs listed above whose transcriptions are up-regulated, Tlr3, Tlr4 and Mda-5, are receptors involved in the recognition of dsRNA viruses. No other PRRs are similarly activated, including Nod, Nalp, Ipaf, Naip, Rage, Rxfp1, and Dai receptors. On the other hand, we have found that the aryl receptor, Ahr, is also up-regulated (unpublished data) which may indicate a role for innate lymphocyte cells (iLCs). Of particular interest is the fact that Mda5 (Ifih1), but not Rig1 (Ddx58), is up-regulated coordinately with the Tlr3/Tlr4 complex, as Mda-5 tends to recognize viruses of the Picornaviridae family (e.g., coxsackie viruses, encephalomyocarditis virus, and rhinoviruses) or the Reoviridae family (e.g., rotovirus), while Rig-1 tends to recognize viruses of the Paramyxoviridae family (e.g., mumps, measles, respiratory syncytial and parainfluenza viruses). A second interesting point involves a large number of the Trim (E3 ubiquitin ligase) family of molecules known to direct molecular mechanisms underlying the cytokine storm observed in immune responses. Thus, the transition appears to evolve from an enhanced innate response to an adaptive autoimmune response, and the response of cells to infectious agents. In essence, genes encoding Trim molecules, whose gene expressions are down-regulated, normally function to suppress the signal transduction pathways of Tlr4, Tlr3 and Mda5. In contrast, the genes encoding Trim molecules, whose expressions are up-regulated, function to enhance Tlr3/Tlr4 and Mda5 signal pathways. Most critical, the gene encoding Trim8, whose function is to suppress expression of Socs (Suppressor of cytokine synthesis-3) [55], is strongly up-regulated, thus resulting in loss of Socs regulation of autoimmunity. Taken as a whole, this profile indicates up-regulation of pathways leading to strong transcription of interferon, pro-inflammatory cytokines and molecules known to activate adaptive responses (e.g., IL6, IL12p40, Rantes, CD40, CD80 and CD56).

Perhaps the most conclusive data of a viral etiology comes from the pattern of up-regulated transcription of Ifn-associated genes activated in response to cell/tissue infections, i.e., the cell autonomous response. During the early inflammation/innate phase, salivary and lacrimal glands express genes whose products are known to block all stages of viral reproduction, including Ifitm, Trim5a, Apobec3, Samhd1, Adar1, Gbp3, Oas, RnaseL, Eif2ak and Tetherin. No such gene pattern was identified for a cell autonomous response to bacteria, fungi, or parasites (unpublished data). Nevertheless, it is important to note that no direct data exists regarding whether or not viruses, known to have strong interactions with Trim molecules, are actually responsible for the temporal differential gene expression profiles observed at the transcriptome level, but evidence for a viral etiology is building.

4.2. The Trim8-Pias-Socs3-TAM RTK pathway regulation of IFN expression

As stated above, Trim8 acts to suppress Socs via a complex set of factor interactions. In turn, Socs molecules are regulated by TAM RTKs (Tyro3, Axl, Mertk tyrosine kinase receptors), the latter identifying apoptotic cells via their major ligands (Gas6 and Protein S). This pathway must be of interest as it plays a critical role in regulating innate immune responses, particularly inhibiting inflammatory responses associated with phagocytosis of apoptotic cells [56,57] as depicted in Fig. 2. A function of Gas6 and Protein S is to link TAM receptors to phosphatidylserine (PS) residues expressed on the membranes of apoptotic cells or cellular debris, thus facilitating phagocytosis [58]. Dysfunctional TAM receptor signaling can result in aberrant phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and membranes, primarily in antigen-presenting cells, leading to over-expansion of myeloid and lymphoid cell populations and subsequently autoimmunity [59]. Dysfunctional TAM receptor signaling is characterized by up-regulations of several downstream signaling pathways and pro-inflammatory factors, including TLRs, p38-Mapk, Erk1/2, Traf3, Traf6, AP-1 transcription factors and multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially TGFβ and the IFNs. Our previous studies [60,61] revealed that genes encoding these various factors, as well as Mertk and Gas6 per se, are up-regulated in salivary glands of C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, but not in salivary glands of C57BL/6J mice.

Cytoplasmic factors involved in TAM RTK signal transductions include Vav, Src, FAK-Ptk2 and Stat3. Not surprising, genes encoding Vav proto-oncogenes (Vav2 and Vav3), the sarcoma tyrosine kinase (Src), focal adhesion kinase FAK (Ptk2) and signal transducer & activator of transcription-3 (Stat3) all exhibited up-regulated expressions in the salivary glands of C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice between 4 and 16 weeks of age when compared to their expressions in the salivary glands of C57BL/6J mice [62]. Since the function of the Mertk system is to regulate or inhibit inflammation primarily by down-regulating activation of macrophages and DCs, Mertk pathway signaling should occur following phagocytosis of apoptotic debris. Studies have shown that both TAM RTK mRNA and protein levels increase in DCs following activation with either TLR agonists or IFN [63–65], and this increased expression of TAM RTKs is dependent on IFN receptors and Stat proteins. The fact that both Stat1 and Stat2 are up-regulated suggests recruitment of Irf9, which would subsequently interact with Isre9 to activate transcription of interferon-inducible genes. Irf9, encoding factor Irf9, shows an up-regulated expression in C57BL/6.NOD-AecaAec2 salivary glands, thus, providing clues to the strong IFN-signature in SS-like disease.

Two regulatory factors in mice that are critical in TAM RTK-associated inhibition of inflammation following apoptotic cell phagocytosis are SOCS1 and SOCS3 [56,57]. SOCS1 and SOCS3 inhibit phosphorylation of STAT, TRAF3 and TRAF6 molecules involved in TLR signal transductions [66–68]. Data from our mouse models indicate that Socs1 gene expression remains totally unchanged in the salivary and lacrimal glands of both C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 and C57BL/6J mice, whereas Socs3 gene expression is markedly down-regulated in the SS-susceptible C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, but strongly up-regulated in the SS-non-susceptible comparative C57BL/6J mice [62]. Polarization of Socs1 versus Socs3 expression observed in this model system is consistent with previously published reports showing selective tissue expressions of the SOCS proteins [62,69]. In any event, the lack of Socs3 expression in the salivary glands of C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice would predict a failure in controlling the basic elements activated during the early inflammatory and innate phases of SS-like disease, thereby facilitating development of auto-inflammation and subsequent autoimmunity.

4.3. A regulatory role for the complement - Il-2 pathway in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and generation of regulatory T cells

Polymorphisms identified in complement factor C1q of humans have been shown to correlate with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [70], but a possible role for complement in either SS or SS-like disease remains highly speculative. Earlier studies in NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice treated with cobra venom suggested a crucial role for C3 in development of salivary and lacrimal gland dysfunction [71]. Results from subsequent transcriptomic studies indicated that transcripts of C1qα, C1qβ and C1qγ, whose products form the core of C1q, are highly up-regulated, while transcription of C1r was minimally elevated and that of C1s actually depressed. Since C1s is essential for activation of the classical complement pathway, one might hypothesize that the complement membrane attack complex plays little or no role in SS-like disease of the salivary gland, a concept supported by the fact that expressions of C6 through C9 transcripts remain unchanged. Furthermore, the transcript levels of both Clu (clusterin) and CD59 (protectin), two membrane attack complex inhibitors, are strongly up-regulated. In contrast, genes comprising the alternate pathway, i.e., Cfb, Cfd, Cfp and C3, were all up-regulated, suggesting the alternate complement pathway is active in the SS-like disease process.

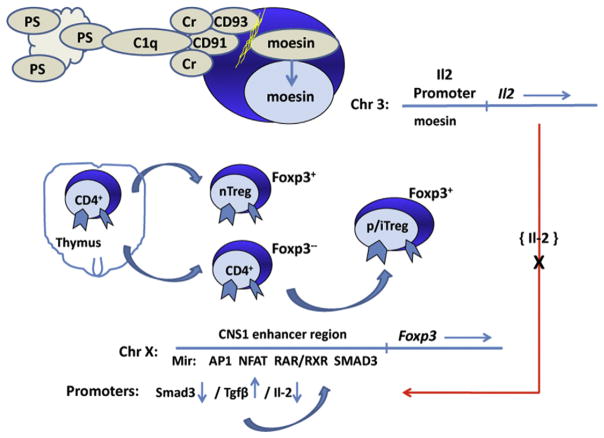

C1q is a known molecule that binds to apoptotic cells to enhance efficient clearance of apoptotic debris, especially by macrophages [72], as shown in Fig. 3. This process is important for tissue homeostasis, antigen-presentation and subsequent TREG cell activation. While deficiencies in a subunit of C1q can increase susceptibility to autoimmunity [70], other factors involved in proper clearance of apoptotic debris by phagocytes include CD91/LRP-1, CD93 and calreticulin. The interaction of C1q with its receptors on phagocytes is mediated by calreticulin, a molecule that ultimately binds to the CD91/LRP-1 receptor expressed in conjunction with CD93. CD93 is a cell surface molecule that is normally tethered to the cytoskeleton via moesin [73]. On CD93 signaling, moesin translocates to the nucleus during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of monocytes, a process involving RAR/PPAR-γ signaling. Unfortunately, RAR/PPAR-γ signaling is hypothesized to be defective in this model [38]. This biological process is of potential importance for SS since moesin, a member of the FERM-domain containing family of proteins that interact with cytosolic tails of trans-membrane proteins, represents an activator of IL2/IL2R pathway [74]. Therefore, one can speculate that this C1q-CD91/Cd93-Moesin pathway, that would normally up-regulate IL-2 production is depressed, which would lead to reduced Foxp3 gene activation and a lower differentiation of regulatory T cells. Thus, studies showing the expression profiles for genes downstream of C1q being either down-regulated or unchanged throughout the course of disease development suggest the mechanism of apoptotic cell clearance may not be functioning properly to maintain gland homeostasis.

Fig. 3.

A potential cascade of molecular events leading to reduced differentiation of regulatory T cells for prevention of autoimmunity. Apoptosis of acinar cells in the salivary gland occurs as a biphasic event, first during early gland development, then during the clinical phase of disease. Studies suggest that C1q and the alternative complement is an active factor in the clearance of apoptotic cells and debris. However, the genes of the moesin signal transduction pathway that normally leads to Il2 gene activation are not up-regulated. Il-2 is an important factor in activation of the Foxp3 gene, thus a reduced IL-2 level, in turn, is hypothesized here to prevent proper activation of TREG cells.

4.4. The TGFβ - Myc axis

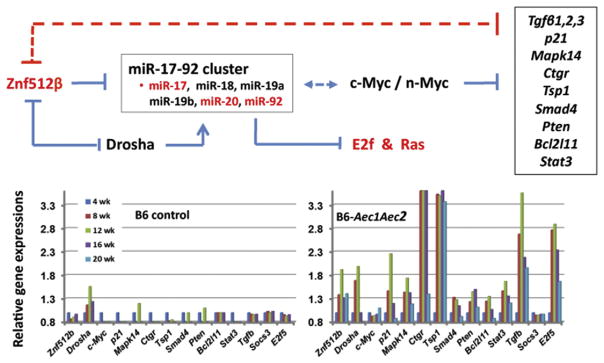

While the early studies of T1D in NOD mice unexpectedly demonstrated a depressed IL-2 level, which may now be described molecularly in the congenic C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse, an equally surprising observation was a strongly up-regulated expression of the three TGFβs (Tgfβ1, β2 and β3). Interestingly, both the Il2 and Tgf biomarker phenotypes of disease transferred to the congenic C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse during its construction, and, importantly, any crossover that replaced the NOD-derived Il2 gene resulted in loss of the SS-like disease phenotype. While the role and/or consequences of the up-regulated expression of Tgfβ1 in SS-like disease remain a mystery, recent studies appear to have identified the molecular mechanism, as depicted in Fig. 4. Normally, there exists a homeostatic equilibrium between Tgfβ1 and the zinc-finger factor, Znf512β. An up-regulated expression of Znf512β results in increased expression of the Tgfβs through the mi17-92 cluster of microRNAs. Tgfβs, in turn, down-regulate Znf512β via the mi17-92 microRNA set. However, if this feedback regulation fails and both factors are up-regulated, the result is a predisposition for autoimmunity, but whether this is an active process in disease development or a downstream result remains to be determined. Nevertheless, an important consequence is the down-regulated expression of Myc (both c-Myc and n-Myc), which permits subsequent up-regulation of factors such as Mapk, p21, Ctgr, Tsp1, Smad, Pten, Bcl2 and Stat3.

Fig. 4.

The face-off between Znf512β and TGFβ mediated by the oncogenic microRNAs of the miR-17-92 cluster in SS-like disease of NOD and C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice. Znf12β is a critical regulator of Myc (c-myc and n-myc), which in turn regulates expression of multiple factors important for many biological processes, especially cell-cell interactions, including the TGFβs [89]. One function of TGFβ is to act as a feedback regulator of Znf512β through up-regulation of miRNAs of the miR-17-92 cluster. A comparison of the temporal transcriptome profiles for many of the factors under control of c-myc (listed in the box) for control C57BL/6 versus autoimmune C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice reveals patterns of activation indicating a suppression of c-myc (and n-myc) inhibitory activity. When both TGFβ and Znf512β are simultaneously over-expressed, as indicated here, there is a correlation with autoimmunity.

4.5. The IL14α - lymphomagenesis connection

While the incidence of lymphomas may be elevated in several auto-immune diseases, perhaps the best example is the increased risk for non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphomas (NHBLs) in patients with SS [75–77]. NHBLs of SS patients can be further classified by histological subtyping to define follicular lymphomas, large B cell lymphomas, and marginal zone lymphomas. Interestingly, such tumors may emerge not only in the salivary glands, but in other mucosal lymphoid tissues such as Peyer’s patches, suggesting a systemic dysregulation of the B-cell populations [78–82]. Although limited information is available regarding the evolution of NHBLs during the clinical stages of SS, it is hypothesized that the rapid and prolonged proliferations of autoreactive cells within the prolonged chronic inflammation leads to accumulation of mutations that ultimately allow the malignant state to emerge [78,79]. This hypothesis also encompasses a possible role for intrinsic abnormalities in lymphocytes of SS patients that selectively promote malignancy in response to environmental insults [83] and/or growth factor stimulations [84].

Identification of early biomarkers for SS-related lymphomas rely on collecting relevant material for examination in order to follow lymphomagenesis temporally at both the genetic and cellular levels. Fortunately, these types of studies are now feasible with recent advances in – omics technology and the recently developed B6·Baff and B6·IL14a TG mice [85]. The interleukin-IL14α transgenic B6·IL14a mouse not only reproduces the clinical and immunological features of SS, but also a temporal development of lymphomagenesis directly correlating with age [25,86,87]. Importantly, lymphomas of these mice are clinically and genetically similar to lymphomas commonly seen in human SS patients, thereby permitting longitudinal and translational studies capable of addressing the evolution of the autoimmune disease and lymphomagenesis simultaneously from both a genetic and immunological perspective. Furthermore, the developing lymphomas can be identified in mice before clinically evident, permitting intervention therapies to be carried out as a means to determine the contributions of various factors to the disease and NHBL progression.

5. Conclusions

Investigations using the various disparate mouse models of SS-like diseases, whether naturally-occurring or induced through genetic manipulations, provide multiple insights into the underlying molecular and biological processes that may form the basis for SS in humans. For the most part, all clinical manifestations observed in the human disease are represented or capitulated in the mouse models when considered as a whole across both species. Furthermore, the genetic diversity of the mouse models presenting with unique sets of manifestations not only indicates multiple clinical phenotypes under different genetic regulations, but seemingly mimics the human disease. In addition, these mouse models have permitted studies of disease development prior to the overt clinical presentation, thus revealing a complex inflammatory phase that apparently establishes an immunological foundation and environment conducive for a subsequent autoimmune response in genetically predisposed animals. The question raised by results from these studies is whether or not these data translate to human SS once individuals can be identified while still in the covert disease phase. Curiously, this early inflammation phase has now been shown using temporal global transcriptomic analyses to be far more complex than the late autoimmune phase [88], providing multiple opportunities for the early diseases of the two species to diverge greatly. In this regard, and totally unexpectedly, our temporal and global transcriptome analyses also reveal a biologically silent period between the inflammatory and autoimmune phases of SS-like disease. Considering this observation, a similar silent period of disease development might be hypothesized to exist between the adaptive autoimmune and lymphomagenesis phases, as well. Thus, there are again opportunities for the disease in mice and human to take different pathways. Nevertheless, these “low activity” time-periods could represent windows for intervention therapies if similar silent periods could be identified in the SS patient population.

Assuming that the early inflammatory phase of the SS-like disease is directly involved in the subsequent autoimmune and lymphomagenesis phases of disease, then changes in the homeostasis of the lacrimal and salivary glands would be expected to provide an opportunity to identify and define the underlying etiopathology at the genetic, molecular and biological level. This possibility is supported by temporal global genomic transcriptomic data generated using C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 and B6·Il14α mice (and no doubt other available mouse models). Most importantly, the temporal changes in gene expressions identified in the transcriptomic data verifies the changes observed in studies defining the histopathological changes, while at the same time, the histopathogical and phenotypic changes observed in vivo verify the transcriptome data. We have presented several examples in this review showing how changes in gene expressions correspond with observed biological phenotypes and complete biological processes when gene sets are created and combined to form molecular pathways. Perhaps the most remarkable example is portrayed by the interferon transcriptome profile of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse model. While the profile of the interferon responsive genes define biological pathways involved in IFN production, they also define a cellular response to an invading microorganism, specifically a dsRNA virus and not a bacterium, fungus or parasite. Thus, these data support the long-term belief that a virus probably is involved in SS, as well.

Just as SS-like mouse models might be able to provide insight into the underlying etiopathophysiology of SS, they also portray in part the diversity of phenotypes observed among SS patients, especially separating those that develop versus those that do not develop lymphomas. This is clearly observed in a comparison between B6·Il14α versus C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice, as discussed herein. One interpretation of the findings that a continuous up-regulated expression of the cytokine IL-14α promotes subpopulations of B lymphocytes to undergo lymphomagenesis as the SS-like disease transitions to its late-phase is that IL-14α per se is involved in genetic and/or epigenetic changes responsible. This would be consistent with the fact that C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice do not demonstrate this up-regulated expression of IL-14α as the mice age. In contrast, C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice exhibit a transient up-regulated expression of Il14α restricted to the early stages of disease development, then down-regulating this cytokine as the disease transitions to the autoimmune phase. This transient expression of IL-14α correlates histologically with the influx, presence and disappearance of B lymphocytes in the salivary and lacrimal glands, thus raising exciting expectations about the molecular role for IL-14α in both mouse and human SS diseases.

The variety of mouse models that have been genetically developed to exhibit a wide spectrum of SS-like disease phenotypes have already permitted classifying SS-like disease as a multi-step, multi-phase process involving an extensive array of molecular and biological processes. Sorting out those processes involved directly in development versus those activated as a result of the onset of a chronic autoimmune disease, as well as those biological processes activated secondarily merely as normal responses to injury of the exocrine glands, also need to be defined to better understand how and why autoimmunity results. Currently, we would hypothesize that SS-like disease represents a failure in apoptotic cell phagocytosis to induce a non-responsive state to self, suggesting a chronic inflammation whose etiology is viral-induced. Thus, having the capability to temporally follow SS-like disease at both a pathophysiological and molecular level in mouse models over the entire development of disease has already provided many insights supporting such a hypothesis. While we believe insights derived from mouse models are relative to the human SS, the depth to which we can translate these mouse model findings to humans remains to be seen.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported financially in part by PHS grants DE023433, DE018958, R03AI122182 (CQN) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Disclosure

Ammon Peck and Cuong Nguyen have no conflict of interest on the topics discussed in the article.

References

- 1.Jonsson R, Dowman SJ, Gordon T. Sjogren’s syndrome. In: Koopman WJ, Moreland LW, editors. Arthritis and Allied Conditions-A Textbook in Rheumatology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. pp. 1681–1705. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox RI. Sjogren’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voigt A, Sukumaran S, Nguyen CQ. Beyond the glands: an in-depth perspective of neurological manifestations in Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Sunnyvale) 2014;2014 doi: 10.4172/2161-1149.S4-010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen L, Suresh L, Lindemann M, Xuan J, Kowal P, Malyavantham K, Ambrus JL., Jr Novel autoantibodies in Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2012;145:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Routsias JG, Tzioufas AG. Sjogren’s syndrome—study of autoantigens and autoantibodies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;32:238–251. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maier-Moore JS, Koelsch KA, Smith K, Lessard CJ, Radfar L, Lewis D, Kurien BT, Wolska N, Deshmukh U, Rasmussen A, Sivils KL, James JA, Farris AD, Scofield RH. Antibody-secreting cell specificity in labial salivary glands reflects the clinical presentation and serology in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:3445–3456. doi: 10.1002/art.38872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavragani CP, Crow MK. Activation of the type I interferon pathway in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nezos A, Gravani F, Tassidou A, Kapsogeorgou EK, Voulgarelis M, Koutsilieris M, Crow MK, Mavragani CP. Type I and II interferon signatures in Sjogren’s syndrome pathogenesis: contributions in distinct clinical phenotypes and Sjogren’s related lymphomagenesis. J Autoimmun. 2015;63:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen CQ, Peck AB. The interferon-signature of Sjogren’s syndrome: how unique biomarkers can identify underlying inflammatory and immunopathological mechanisms of specific diseases. Front Immunol. 2013;4:142. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordmark G, Eloranta ML, Ronnblom L. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome and the type I interferon system. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:2054–2062. doi: 10.2174/138920112802273290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masaki Y, Sugai S. Lymphoproliferative disorders in Sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:175–182. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocturne G, Mariette X. Sjogren syndrome-associated lymphomas: an update on pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:317–327. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambrus JL, Suresh L, Peck A. Multiple roles for B-lymphocytes in Sjogren’s syndrome. J Clin Med. 2016;5 doi: 10.3390/jcm5100087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killedar SJ, Eckenrode SE, McIndoe RA, She JX, Nguyen CQ, Peck AB, Cha S. Early pathogenic events associated with Sjogren’s syndrome (SjS)-like disease of the NOD mouse using microarray analysis. Lab Investig. 2006;86:1243–1260. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donate A, Voigt A, Nguyen CQ. The value of animal models to study immunopathology of primary human Sjogren’s syndrome symptoms. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:469–481. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.883920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park YS, Gauna AE, Cha S. Mouse models of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:2350–2364. doi: 10.2174/1381612821666150316120024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delaleu N, Nguyen CQ, Peck AB, Jonsson R. Sjogren’s syndrome: studying the disease in mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:217. doi: 10.1186/ar3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scofield RH, Asfa S, Obeso D, Jonsson R, Kurien BT. Immunization with short peptides from the 60-kDa Ro antigen recapitulates the serological and pathological findings as well as the salivary gland dysfunction of Sjogren’s syndrome. J Immunol. 2005;175:8409–8414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szczerba BM, Kaplonek P, Wolska N, Podsiadlowska A, Rybakowska PD, Dey P, Rasmussen A, Grundahl K, Hefner KS, Stone DU, Young S, Lewis DM, Radfar L, Scofield RH, Sivils KL, Bagavant H, Deshmukh US. Interaction between innate immunity and Ro52-induced antibody causes Sjogren’s syndrome-like disorder in mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:617–622. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iizuka M, Wakamatsu E, Tsuboi H, Nakamura Y, Hayashi T, Matsui M, Goto D, Ito S, Matsumoto I, Sumida T. Pathogenic role of immune response to M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in Sjogren’s syndrome-like sialoadenitis. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimori I, Bratanova T, Toshkov I, Caffrey T, Mogaki M, Shibata Y, Hollingsworth MA. Induction of experimental autoimmune sialoadenitis by immunization of PL/J mice with carbonic anhydrase II. J Immunol. 1995;154:4865–4873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleck M, Kern ER, Zhou T, Lang B, Mountz JD. Murine cytomegalovirus induces a Sjogren’s syndrome-like disease in C57Bl/6-lpr/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2175–2184. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2175::AID-ART12>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler HS, Cubberly M, Manski W. Eye changes in autoimmune NZB and NZB x NZW mice. Comparison with Sjogren’s syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:211–219. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.00990050213016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Nakagawa Y, Purushotham KR, Humphreys-Beher MG. Functional changes in salivary glands of autoimmune disease-prone NOD mice. Am J Phys. 1992;263:E607–E614. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.4.E607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford RJ, Shen L, Lin-Lee YC, Pham LV, Multani A, Zhou HJ, Tamayo AT, Zhang C, Hawthorn L, Cowell JK, Ambrus JL., Jr Development of a murine model for blastoid variant mantle-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2007;109:4899–4906. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groom J, Kalled SL, Cutler AH, Olson C, Woodcock SA, Schneider P, Tschopp J, Cachero TG, Batten M, Wheway J, Mauri D, Cavill D, Gordon TP, Mackay CR, Mackay F. Association of BAFF/BLyS overexpression and altered B cell differentiation with Sjogren’s syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:59–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI14121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha S, Nagashima H, Brown VB, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Two NOD Idd-associated intervals contribute synergistically to the development of autoimmune exocrinopathy (Sjogren’s syndrome) on a healthy murine background. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/art.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cha S, Nagashima H, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. IDD3 and IDD5 alleles from nod mice mediate Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506:1035–1039. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cha S, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Progress in understanding autoimmune exocrinopathy using the non-obese diabetic mouse: an update. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:5–16. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen CQ, Kim H, Cornelius JG, Peck AB. Development of Sjogren’s syndrome in nonobese diabetic-derived autoimmune-prone C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mice is dependent on complement component-3. J Immunol. 2007;179:2318–2329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen CQ, Hu MH, Li Y, Stewart C, Peck AB. Salivary gland tissue expression of interleukin-23 and interleukin-17 in Sjogren’s syndrome: findings in humans and mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:734–743. doi: 10.1002/art.23214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jie G, Jiang Q, Rui Z, Yifei Y. Expression of interleukin-17 in autoimmune dacryoadenitis in MRL/lpr mice. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:865–871. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.497600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin X, Rui K, Deng J, Tian J, Wang X, Wang S, Ko KH, Jiao Z, Chan VS, Lau CS, Cao X, Lu L. Th17 cells play a critical role in the development of experimental Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1302–1310. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voigt A, Esfandiary L, Nguyen CQ. Sexual dimorphism in an animal model of Sjogren’s syndrome: a potential role for Th17 cells. Biol Open. 2015;4:1410–1419. doi: 10.1242/bio.013771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voigt A, Esfandiary L, Wanchoo A, Glenton P, Donate A, Craft WF, Craft SL, Nguyen CQ. Sexual dimorphic function of IL-17 in salivary gland dysfunction of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 model of Sjogren’s syndrome. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38717. doi: 10.1038/srep38717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JT, Cornelius JG, Jarpe AJ, Winter WE, Peck AB. Insulin-dependent diabetes in the NOD mouse model. II. Beta cell destruction in autoimmune diabetes is a TH2 and not a TH1 mediated event. Autoimmunity. 1993;15:113–122. doi: 10.3109/08916939309043886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen CQ, Cha SR, Peck AB. Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS)-like disease of mice: the importance of B lymphocytes and autoantibodies. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1767–1789. doi: 10.2741/2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen CQ, Cornelius JG, Cooper L, Neff J, Tao J, Lee BH, Peck AB. Identification of possible candidate genes regulating Sjogren’s syndrome-associated autoimmunity: a potential role for TNFSF4 in autoimmune exocrinopathy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R137. doi: 10.1186/ar2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavill D, Waterman SA, Gordon TP. Antiidiotypic antibodies neutralize autoantibodies that inhibit cholinergic neurotransmission. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3597–3602. doi: 10.1002/art.11343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavill D, Waterman SA, Gordon TP. Antibodies raised against the second extracellular loop of the human muscarinic M3 receptor mimic functional autoantibodies in Sjogren’s syndrome. Scand J Immunol. 2004;59:261–266. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cha S, Singson E, Cornelius J, Yagna JP, Knot HJ, Peck AB. Muscarinic acetylcholine type-3 receptor desensitization due to chronic exposure to Sjogren’s syndrome-associated autoantibodies. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishimaru N, Arakaki R, Yoshida S, Yamada A, Noji S, Hayashi Y. Expression of the retinoblastoma protein RbAp48 in exocrine glands leads to Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmune exocrinopathy. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2915–2927. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, Tschopp J, Browning JL. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1697–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson MS, Bluestone JA. The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:447–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson CP, Yamachika S, Bounous DI, Brayer J, Jonsson R, Holmdahl R, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. A novel NOD-derived murine model of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:150–156. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199801)41:1<150::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindqvist AK, Nakken B, Sundler M, Kjellen P, Jonsson R, Holmdahl R, Skarstein K. Influence on spontaneous tissue inflammation by the major histocompatibility complex region in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61:119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2005.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawke CG, Painter DM, Kirwan PD, Van Driel RR, Baxter AG. Mycobacteria an environmental enhancer of lupus nephritis in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology. 2003;108:70–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quintana FJ, Pitashny M, Cohen IR. Experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in naive non-obese diabetic (NOD/LtJ) mice: susceptibility associated with natural IgG antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor. Int Immunol. 2003;15:11–16. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rozzo SJ, Vyse TJ, Menze K, Izui S, Kotzin BL. Enhanced susceptibility to lupus contributed from the nonautoimmune C57BL/10, but not C57BL/6, genome. J Immunol. 2000;164:5515–5521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cha S, Brayer J, Gao J, Brown V, Killedar S, Yasunari U, Peck AB. A dual role for interferon-gamma in the pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmune exocrinopathy in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Scand J Immunol. 2004;60:552–565. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cha S, van Blockland SC, Versnel MA, Homo-Delarche F, Nagashima H, Brayer J, Peck AB, Humphreys-Beher MG. Abnormal organogenesis in salivary gland development may initiate adult onset of autoimmune exocrinopathy. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 2001;18:143–160. doi: 10.1159/000049194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peck AB, Nguyen CQ. Transcriptome analysis of the interferon-signature defining the autoimmune process of Sjogren’s syndrome. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peck AB, Nguyen CQ, Sharma A, McIndoe RA, She JX. The interferon-signature of Sjögren’s syndrome: what does it say about the etiopathology of autoimmunity. J Clin Rheum Musculoskelet Med. 2011;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toniato E, Chen XP, Losman J, Flati V, Donahue L, Rothman P. TRIM8/GERP RING finger protein interacts with SOCS-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37315–37322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dransfield I, Zagorska A, Lew ED, Michail K, Lemke G. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase mediates both tethering and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1646. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lemke G, Burstyn-Cohen T. TAM receptors and the clearance of apoptotic cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1209:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stitt TN, Conn G, Gore M, Lai C, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Mattsson K, Fisher J, Gies DR, Jones PF, et al. The anticoagulation factor protein S and its relative, Gas6, are ligands for the Tyro 3/Axl family of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1995;80:661–670. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Q, Lemke G. Homeostatic regulation of the immune system by receptor tyrosine kinases of the Tyro 3 family. Science. 2001;293:306–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1061663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nguyen CQ, Sharma A, Lee BH, She JX, McIndoe RA, Peck AB. Differential gene expression in the salivary gland during development and onset of xerostomia in Sjogren’s syndrome-like disease of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R56. doi: 10.1186/ar2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen CQ, Sharma A, She JX, McIndoe RA, Peck AB. Differential gene expressions in the lacrimal gland during development and onset of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in Sjogren’s syndrome (SJS)-like disease of the C57BL/6.NOD-Aec1Aec2 mouse. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wanchoo A, Voigt A, Peck AB, Nguyen CQ. TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK receptor tyrosine kinases: is there evidence of direct involvement in development and onset of Sjögren’s syndrome? EMJ Rheumatol. 2016;3:8. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rothlin CV, Lemke G. TAM receptor signaling and autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshimura A, Nishinakamura H, Matsumura Y, Hanada T. Negative regulation of cytokine signaling and immune responses by SOCS proteins. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:100–110. doi: 10.1186/ar1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wormald S, Hilton DJ. The negative regulatory roles of suppressor of cytokine signaling proteins in myeloid signaling pathways. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:9–15. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen JQ, Szodoray P, Zeher M. Toll-like receptor pathways in autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8473-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McBerry C, Gonzalez RM, Shryock N, Dias A, Aliberti J. SOCS2-induced proteasome-dependent TRAF6 degradation: a common anti-inflammatory pathway for control of innate immune responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walsh MC, Lee J, Choi Y. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) regulation of development, function, and homeostasis of the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2015;266:72–92. doi: 10.1111/imr.12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Stewart KN, Bishop E, Marek CJ, Kluth DC, Rees AJ, Wilson HM. Unique expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 is essential for classical macrophage activation in rodents in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;180:6270–6278. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Botto M, Walport MJ. C1q, autoimmunity and apoptosis. Immunobiology. 2002;205:395–406. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nguyen C, Cornelius J, Singson E, Killedar S, Cha S, Peck AB. Role of complement and B lymphocytes in Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmune exocrinopathy of NOD.B10-H2b mice. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1332–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tarr J, Eggleton P. Immune function of C1q and its modulators CD91 and CD93. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:305–330. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burkhardt JK, Carrizosa E, Shaffer MH. The actin cytoskeleton in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:233–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Frame MC, Patel H, Serrels B, Lietha D, Eck MJ. The FERM domain: organizing the structure and function of FAK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:802–814. doi: 10.1038/nrm2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mackay IR, Rose NR. Autoimmunity and lymphoma: tribulations of B cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:793–795. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ekstrom Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, Engels EA, Martinez-Maza O, Turner J, Hjalgrim H, Vineis P, Seniori Costantini A, Bracci PM, Holly EA, Willett E, Spinelli JJ, La Vecchia C, Zheng T, Becker N, De Sanjose S, Chiu BC, Dal Maso L, Cocco P, Maynadie M, Foretova L, Staines A, Brennan P, Davis S, Severson R, Cerhan JR, Breen EC, Birmann B, Grulich AE, Cozen W. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111:4029–4038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Voulgarelis M, Skopouli FN. Clinical, immunologic, and molecular factors predicting lymphoma development in Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;32:265–274. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hansen A, Reiter K, Pruss A, Loddenkemper C, Kaufmann O, Jacobi AM, Scholze J, Lipsky PE, Dorner T. Dissemination of a Sjogren’s syndrome-associated extranodal marginal-zone B cell lymphoma: circulating lymphoma cells and invariant mutation pattern of nodal Ig heavy- and light-chain variable-region gene rearrangements. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:127–137. doi: 10.1002/art.21558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Voulgarelis M, Moutsopoulos HM. Lymphoproliferation in autoimmunity and Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003;5:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s11926-003-0011-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manganelli P, Fietta P, Quaini F. Hematologic manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:438–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris NL. Lymphoid proliferations of the salivary glands. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:S94–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Askling J, Chang ET, Gregersen H, Porwit-MacDonald A, Sundstrom C, Akerman M, Melbye M, Glimelius B, Adami HO. Autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma by subtype. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:51–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borchers AT, Naguwa SM, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Immunopathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;25:89–104. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:25:1:89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seto M. Genetic and epigenetic factors involved in B-cell lymphomagenesis. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:704–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiorini JA, Cihakova D, Ouellette CE, Caturegli P. Sjogren syndrome: advances in the pathogenesis from animal models. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shen L, Suresh L, Li H, Zhang C, Kumar V, Pankewycz O, Ambrus JL., Jr IL-14 alpha, the nexus for primary Sjogren’s disease in mice and humans. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shen L, Gao C, Suresh L, Xian Z, Song N, Chaves LD, Yu M, Ambrus JL., Jr Central role for marginal zone B cells in an animal model of Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2016;168:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Delaleu N, Nguyen CQ, Tekle KM, Jonsson R, Peck AB. Transcriptional landscapes of emerging autoimmunity: transient aberrations in the targeted tissue’s extracellular milieu precede immune responses in Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R174. doi: 10.1186/ar4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Liu CG, Alder H, Taccioli C, Volinia S, Calin GA, Croce CM. GAM/ZFp/ZNF512B is central to a gene sensor circuitry involving cell-cycle regulators, TGF{beta} effectors, Drosha and microRNAs with opposite oncogenic potentials. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7673–7688. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]