Abstract

Criminal convictions are often associated with collateral consequences that limit access to the forms of employment and social services on which disadvantaged women most frequently rely – regardless of the severity of the offense. These consequences may play an important role in perpetuating health disparities by socioeconomic status and gender. We examined the extent to which research studies to date have assessed whether a criminal conviction might influence women’s health by limiting access to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and employment, as a secondary, or “collateral” criminal conviction-related consequence. We reviewed 434 peer-reviewed journal articles retrieved from three electronic article databases and 197 research reports from three research organizations. Two reviewers independently extracted data from each eligible article or report using a standardized coding scheme. Of the sixteen eligible studies included in the review, most were descriptive. None explored whether receiving TANF modified health outcomes, despite its potential to do so. Researchers to date have not fully examined the causal pathways that could link employment, receiving TANF, and health, especially for disadvantaged women. Future research is needed to address this gap and to understand better the potential consequences of the criminal justice system involvement on the health of this vulnerable population.

Keywords: criminal involvement, employment, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), health

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, the criminal justice system has been implicated in playing a key role in generating and perpetuating health disparities (Binswanger et al. 2012; Burris 2002). Research has yielded substantial information about the direct effects of criminal justice involvement on health through communicable disease transmission in correctional facilities (i.e., tuberculosis, HIV) and inadequate health care services for incarcerated populations (Binswanger et al. 2012). The criminal justice system may, however, also indirectly influence health through a set of collateral consequences that follow minor criminal convictions that do not result in a jail or prison sentence.

Collateral consequences are legally- and socially-imposed penalties or disadvantages that automatically occur upon a person’s conviction for a felony, misdemeanor, or other offense, and are imposed in addition to the sentence enacted by the court (American Bar Association 2004). These consequences operate across multiple systems that influence peoples’ everyday lives, can be imposed for a finite period of time or for life, can occur in response to virtually every type of criminal conviction, and affect a significant portion of the population. Collateral consequences can include, among other consequences, losing access to job opportunities, and/or becoming ineligible to receive public assistance benefits (Chin 2002). Given the well documented, positive association that employment and income have on health (Roelfs et al. 2011; Rueda et al. 2012), the barriers to becoming employed and/or participating in income support programs that occur as collateral consequences would be expected to have deleterious effects on health.

Understanding the relationship between criminal convictions and health is critical given the increased reach of the criminal justice system in the U.S., as well as its growing importance among women. The number of women involved in the criminal justice system has increased dramatically in recent decades: between 1985 and 2008, the rate of imprisonment among women quadrupled (White House Council on Women and Girls 2011); and, in 2011, one in four adults on probation and over one in ten adults on parole were women (Maruschak and Parks 2012). These statistics highlight the importance of incarceration among women; however, incarcerated individuals account for only 3.5 percent of adults with a history of a criminal conviction in the U.S. (Glaze 2011). While no statistics focus specifically on women, data show that over 65 million Americans have been convicted of a crime (Rodriguez and Emsellem 2011), and in 2010 alone, U.S. courts processed over 102 million criminal cases (United States Sentencing Commission 2010). By solely focusing on the relationship between incarceration and health, existing studies may underestimate the important indirect effects on health the criminal justice system may have through collateral consequences.

As with other determinants of health in the U.S., the pathways through which collateral consequences operate are not socioeconomic status-, race-, or gender-neutral: rather, they are realized through labor market and public welfare systems in ways that predominantly affect women who are socially or economically disadvantaged—that is, who are poor, are racial/ethnic minorities, and/or have a very low level of education (henceforth referred to as disadvantaged women) (Burgess-Proctor 2006). Indeed, data on women involved in the criminal justice system reveal that they have many interconnected social and health characteristics that make them a particularly vulnerable population (Freudenberg 2001). Specifically, according to Bloom, Owen, and Covington (2004), women involved in the criminal justice system are disproportionately single mothers of color in their early- to mid-thirties. They have multiple attributes that influence their ability to obtain and maintain employment, such as experiencing physical and sexual abuse, as well being diagnosed with mental health conditions, such as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse. Relatedly, women in the criminal justice system also have limited educational attainment as well as sporadic work histories in entry-level jobs with low pay. Given the pressing economic and personal needs of this population, it is not surprising that women’s most frequent pathways into the criminal justice system result from attempts to survive abuse, poverty, and substance abuse (Bloom, Owen, and Covington 2005).

Central to the goals of this review, having a criminal offense history may compound these background characteristics, which may further limit employment opportunities for women. Rigorous studies assessing employers’ willingness to hire applicants with histories of incarceration have used an experimental audit design in which white and black male actors with and without incarceration histories applied for jobs. Study results demonstrated that actors with an incarceration history were 50 percent less likely to be called back for an interview. This effect was intensified by race: only 8–14 percent of blacks with an incarceration history were called back, compared to 17–29 percent of whites with an identical criminal record (Pager 2003; Pager, Western, and Sugie 2009). Consistent with these findings, in a study of employer attitudes and practices, only 20 percent of 619 employers indicated they would hire an applicant with a criminal record history (Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2003). These studies focused on the difficulties faced by men in obtaining employment after incarceration; however, women with criminal records are likely to face similar barriers to employment. Although women typically commit less serious types of offenses than men, such as financially-motivated misdemeanors (Schwartz and Steffensmeier 2007), these non-violent offenses are still likely to result in lifelong restrictions on working in the lower-income service sector jobs and industries that are likely to employ women (i.e., child care, human services) (Rodriguez and Emsellem 2011). A study of employers, for example, found that service industry employers—who represent the labor market sector most likely to hire women—were the least willing to hire ex-offenders (Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2003).

Additionally, women who have committed criminal offenses may be barred from access to some of the social service programs on which they rely for economic survival, such as public housing, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. With the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation of 1996 (welfare reform), federal lawmakers gave states the option of denying TANF and SNAP benefits to applicants convicted of a felony drug offense. Currently, fourteen states have adopted the federal lifetime ban on benefits; an additional twenty-two states partially enforce the ban by allowing access to benefits after an allotted period of time or by allowing individuals to have access to either TANF or SNAP (Pinard 2010). While TANF, SNAP, and public housing benefits are all important economic supports for formerly incarcerated women that may help them provide shelter and food for their families before securing employment (Bloom, Owen, and Covington 2004), restrictions on TANF may be particularly detrimental as only TANF provides the employment training and job placement services that could directly improve employment outcomes. For example, TANF programs often have extended employer-based networks at the local level that include employers more willing to consider hiring individuals with a prior criminal conviction.

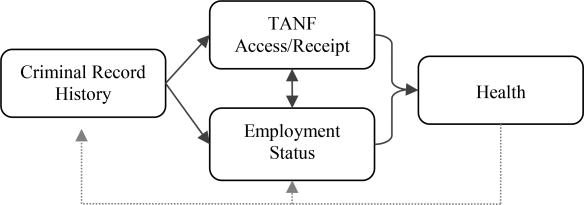

Given the complexity of the pathways through which a criminal conviction history might influence women’s health, our review had both a theoretical and substantive aim. From the theoretical perspective, we sought to understand researchers’ conceptualizations of the relationships among: (1) a criminal conviction; the collateral consequences of restricted (2) employment and (3) receiving TANF that can occur following a criminal conviction; and (4) health. Additionally, our substantive aim was to determine whether any findings suggested that a criminal conviction history might indirectly be related to women’s health via employment and/or receiving TANF, given the way these factors uniquely interact as likely social determinants of health in women’s lives (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Linking Criminal Record-Related Collateral Consequences to Health

METHODS

To address these questions, we conducted a systematic research synthesis of the existing research on these topics. Systematic literature reviews in the health and social sciences are typically conducted with the primary goal of assessing the strength of evidence available in a particular content area. While such reviews yield important information and are readily recognized by researchers across disciplines, they are distinctly different from this research synthesis. Like systematic reviews, a research synthesis uses ‘systematic’ steps to select relevant studies, as well as extract and analyze data; however, research syntheses can serve many different purposes other than assessing the strength of findings from a body of research (Cooper 2010). For example, research syntheses may be used to examine the predominant theoretical frameworks applied in a particular area of research, or to assess the consistency of measures used in a particular body of literature. Overall, our goal was to synthesize what is present, generate conclusions about how the frameworks or measures applied have shaped the scope and direction of the research conducted to date, and offer recommendations for how to advance the science in the field. The methods applied here for study selection, data extraction, and analysis are consistent with a research synthesis approach. The aims of this study were to determine: (1) how researchers have conceptualized the relationships among criminal record histories, TANF receipt, employment, and health; (2) whether TANF receipt and/or employment have been specifically included in study designs as either moderating or mediating the effect a criminal conviction might have on health; and (3) based on research findings, what the implications these finding may have for understanding how collateral consequences from a criminal conviction related to TANF receipt and employment may act as social determinants of women’s health.

Study Selection

We searched PUBMED, and Gale Academic One File databases for peer reviewed journal articles published from 1990 to August 2012. Gale Academic One File incorporates PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Business Source Complete search engines, and includes an extensive list of peer-reviewed journals from sociology. In addition, we also analyzed reports gathered from three policy-focused research centers with a long history of conducting studies related to the topic of interest in this synthesis—the Urban Institute, Mathematica, and MDRC. Many, if not most, of the study findings from these centers/institutes are published in internally-generated reports (i.e., the “grey literature”) rather than in peer-reviewed journals. We include these reports given: (1) the focus of this synthesis on evaluating how researchers have conceptualized the relationships among women’s criminal record histories, TANF receipt, employment, and health rather than assessing the quality of the findings; and (2) the substantial amount of research conducted by these centers. For both journal articles and research reports, we searched for keywords in the title and abstract related to criminal justice involvement (criminal record, criminal conviction, criminal background), health, employment, and TANF (TANF, or “welfare”). Studies related to incarceration were only included if they focused on community reentry in order to ensure that articles would be relevant to collateral consequences rather than incarceration.

Inclusion criteria for study reports were: (1) information on criminal conviction of any type, and (2) that the relationship between the criminal conviction and the use of TANF, employment, and/or health outcomes was a focus of interest in the study. We excluded study reports if: (1) they were not written in English, (2) the study population was outside the United States, (3) the study did not include findings about women, (4) they were not reports of study findings, (5) they were dissertation abstracts, (6) the primary study outcome was drug treatment completion, (7) the study focused on child outcomes, or (8) if the primary outcome of the study was recidivism, given we were most interested in what consequences follow a conviction, rather than what factors lead to convictions.

Data Extraction

Both researchers extracted data for the synthesis using a standardized form that information on the following: study purpose; study design; criminal record measurement source; criminal record level (arrest, conviction, incarceration), severity (misdemeanor, felony, both, or unspecified) and offense type; sample size and demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, age, educational attainment); standardized measures; sampling method; methodological limitations; and how the relationships between a criminal record, employment, TANF, and health were conceptualized in the study design.

RESULTS

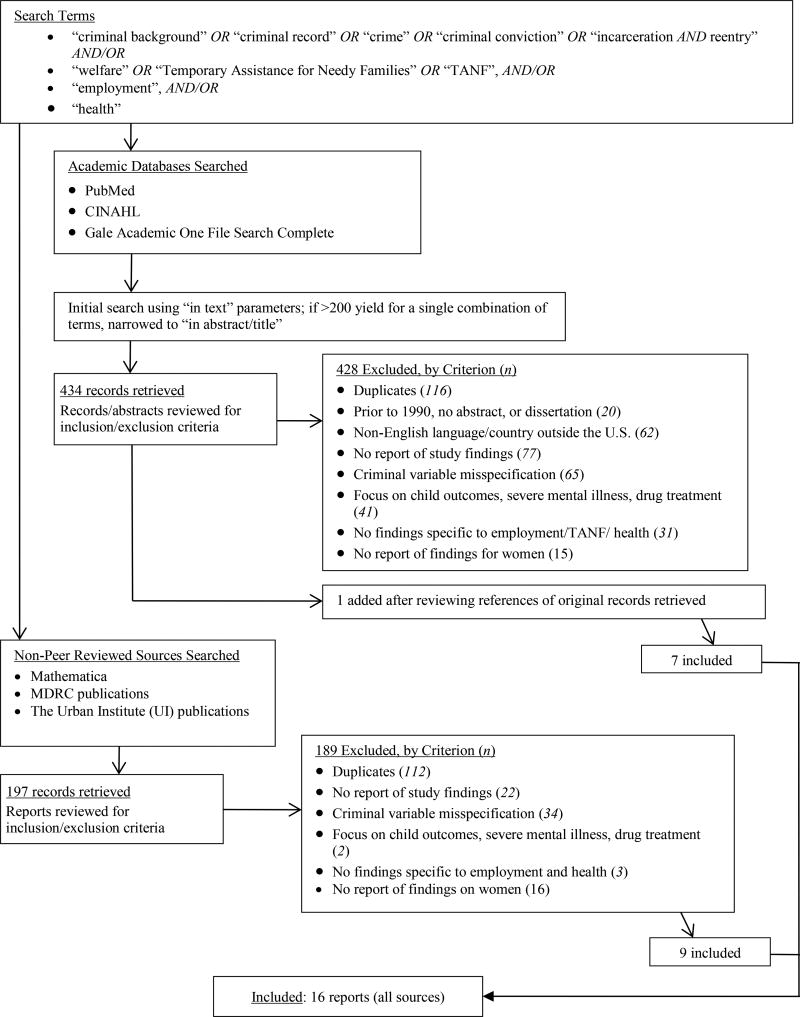

We retrieved 434 peer-reviewed journal articles and 197 reports from the grey literature. Of these, 428 and 188 were excluded, respectively. One additional journal article was added after reviewing the references of the original records retrieved. Overall, sixteen reports were included in the review. A detailed algorithm that follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) criteria (Grzywacz et al. 2004) is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Search Strategy for Research Synthesis Related to Criminal Records, Employment, TANF Use, and Health

Description of Evidence

Most studies either used a qualitative (n = 7, or 44 percent) or descriptive (n = 4, or 25 percent) research design (Table 1). As an example of a descriptive design, Acs and Loprest (2003) described employment barriers among a representative sample of single-parent TANF recipients, which included their overall physical health, mental health, substance use, and having a criminal record. Three studies (19 percent) were group comparison designs, and two studies (13 percent) included multivariate analysis. Half (50 percent, or n = 8) were cross-sectional, most focused on formerly incarcerated populations (63 percent, n = 10), and had samples that were predominantly African American (63 percent, n = 10).

Table 1.

Select Characteristics of Study Reports Included (n=16)

| Study Overviewa | Sample Detailsb | Measurement of Key Variablesc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Author(s) & Year | Study Design | Incarceration -focused? |

% Women | % African American |

Criminal Record |

Employment | TANF | Health |

| Acs & Loprest (2003) | DescriptiveX | N | 100 | n/s | DESC | DESC | TSC | DESC |

| Arditti et al. (2006) | Qualitative | Y | 100 | 20 | TSC | QUAL | NR | QUAL |

| Arditti & Few (2008) | Qualitative | Y | 100 | 18.5 | TSC | QUAL | NR | QUAL |

| Brock et al (2002) | Group ComparisonL | N | 100 | 80 | IV | DV | TSC | DESC |

| Brown & Bloom (2009) | Qualitative | Y | 100 | n/s | TSC | DESC | QUAL | QUAL |

| Brown & Barbosa (2001) | QualitativeX | N | 100 | 89 | QUAL | TSC | QUAL | QUAL |

| Heilbrun et al. (2008) | Group comparison | Y | 38 | M=72, W=59 | TSC | DESC | NR | DESC |

| LaVigne et al. (2009) | MultivariateC | Y | 100 | 63 | TSC | DESC | NR | DESC |

| Lattimore et al. (2009) | Group ComparisonL | Y | 15 | M=50, W=41 | TSC | DV | NR | DV |

| Luther et al. (2011) | QualitativeX | Y | 57 | M=95, W=48 | TSC | QUAL | NR | QUAL |

| Malik-Kane & Visher (2008) | MultivariateC | Y | 39 | M=95, W=52 | TSC | DV | NR | IV |

| Michalopoulos et al. (2003) | DescriptiveX | N | 100 | 77 | DESC | DESC | TSC | DESC |

| Morgenstern et al. (2002) | DescriptiveX | N | 100 | 90 | DESC | DV | TSC | TSC |

| Quint et al. (1999) | QualitativeX | N | 100 | n/s | QUAL | DESC | TSC | NR |

| Van Olphen et al. (2009) | QualitativeX | Y | 100 | 59 | TSC | QUAL | NR | QUAL |

| Visher et al. (2004) | QualitativeL | Y | 27 | 83 | TSC | DESC | DESC | DESC |

Study overview abbreviations: C: Controlling for confounding; X: Cross-sectional; L: Longitudinal;

Sample detail abbreviations: n/s: Not stated; n/a: Not applicable

Measurement of key variables abbreviations: DESC: Descriptive variable in study; DV: Dependent variable; IV: Independent variable; NR: Not represented in the study; TSC: Target sample characteristic; QUAL: Emergent as qualitative theme/finding.

Conceptualization of Relationships Among Variables of Interest

Given our search criteria, all studies included information about criminal involvement. Additionally, all of the studies in the review included data on employment. Almost all of the studies included health-related variables (n = 15, or 94 percent), while studies were least likely to include variables related to receiving TANF (n = 9, or 56 percent). Forty four percent (n = 7) incorporated all four variables of interest to this review (i.e., criminal record history, receiving TANF, employment, and health).

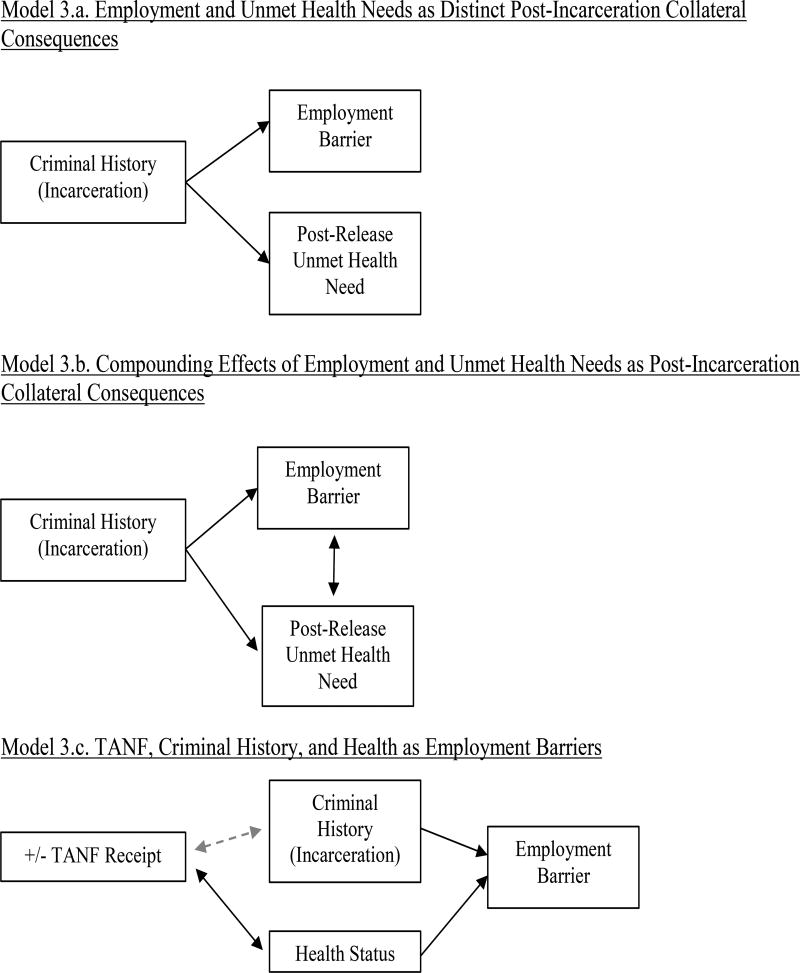

All of the studies in this review included some data on the employment of women involved in the criminal justice system, and fifteenof the sixteen studies also included information on their health. While criminal justice involvement, employment, and health were assessed in most of the studies, studies conceptualized the relationships between these variables in different ways: five of the studies assessed employment and health as distinct negative outcomes resulting from engagement with the criminal justice system (model 3.a, Figure 3); six studies examined the relation of health and employment to having a criminal record, but also described the ways in which lack of employment was associated with poor health and vice versa (model 3.b, Figure 3); and five studies considered the ways in which poor health and criminal convictions act as employment barriers among recipients of TANF (model 3.b., Figure 3). We will describe the findings from each group of these studies below.

Figure 3.

Research Studies Related to Key Variables of Interest

By comparing the model of relationships sought as the basis for this synthesis (Figure 1) to the models depicting the relationships between the variables of interest found in the literature (Figure 3), a major finding of the synthesis was that none of the studies reviewed examined the ways in which TANF or employment could mediate or moderate the effect of a criminal conviction history on health.

Employment and Unmet Health Needs as Distinct Post-Incarceration

Collateral Consequences

The sample of interest for four studies was women returning to the community after incarceration (Heilbrun et al. 2008; Lattimore and Visher 2009; La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009; Visher et al. 2004), while one study interviewed low-income women seeking job training services about their barriers to employment (Brown and Barbosa 2001) (model 3.a, Figure 3). In terms of employment outcomes, all of the studies examining employment after incarceration repeatedly identified the negative relationship between incarceration and employment (Brown and Barbosa 2001; Heilbrun et al. 2008; Lattimore et al. 2009; La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009; Visher et al. 2004). Employment was ranked as one of the highest priorities of inmates being released from prison (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009). Even though 58 percent of women had worked in the 6 months prior to being incarcerated in one study, only 34 percent were employed 8 months post-release (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009). Three of these studies also compared employment outcomes among formerly incarcerated men and women (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009; Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008; Lattimore and Visher 2009); they documented that women reentering the community had lower employment rates over time. Whereas employment rates increased on average 13 percent over time post-release for men, they increased for women by only 4 percent over an 8- to 9-month period (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009; Lattimore and Visher 2009). Additionally, women reentering the community had lower wages (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009; Visher et al. 2004), were less likely to find full-time work (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009), and were more likely to report financial difficulties (Heilbrun et al. 2008) than men. However, it is important to note that these women also had lower rates of employment, as well as hourly wages, before incarceration as well (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009). Lastly, the findings from a large intervention study suggests employment outcomes for recently incarcerated women and men may only be transiently improved through more intensive interventions that provide temporary and/or subsidized employment, job-training, job preparation, job search assistance, and other reintegration supports (Lattimore and Visher 2009).

These studies also document the significant health needs of formerly incarcerated women. Visher and colleagues (2004) find that, among their sample of women reentering the community after incarceration, 38.2 percent said that they have experienced serious depression, sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest in the past 30 days and 29 percent said that they had problems understanding and concentrating. Women were more likely to experience these symptoms than men in the sample. In another study, 67 percent of women were diagnosed with a chronic health condition after leaving prison (La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger 2009).

The Compounding Relation of Post-Incarceration Collateral

Consequences to Employment and Health

Six of the studies in this review examined both the ways in which criminal convictions were negatively related to health and employment among women. One important feature of this set of studies included depicting the processes—or mechanisms—through which poor health and unemployment intersected and compounded health risks over time (model 3.b, Figure 3) (Arditti and Few 2006, 2008; Brown and Bloom 2009; Luther et al. 2011; Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008; van Olphen et al. 2009). The samples of all of these studies were formerly incarcerated women, and all but one study (Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008) used a qualitative research design. The findings of these studies support research in the last section showing the negative relation of criminal justice involvement to employment and, subsequently, health. For example, Mallik-Kane and Visher (2008) found that 77 percent of recently incarcerated women reported having a chronic physical or mental health condition, and only 40 percent of women had some type of health insurance coverage. This study also found additive effects of a criminal record history and poor health in relation to employment, including the finding that health problems were associated with a 13 percent decreased probability of employment (Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008).

Four qualitative studies explored the mechanisms through which a criminal record history and subsequent unemployment could influence health. These studies clearly identified the inability to find employment after involvement with the criminal justice system as eliciting fear of being rejected or stigmatized in employment application encounters (Brown and Bloom 2009), hopelessness (Luther et al. 2011), and depression (van Olphen et al. 2009). Studies also link the inability to get a job with feelings of “maternal distress,” in which the inability to provide financial resources for their children exacerbates existing mental health problems among formerly incarcerated mothers (Arditti and Few 2006, 2008). Another qualitative study documents that women coped with a lack of financial resources when leaving prison by engaging in prostitution, which left them with an increased exposure risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (Luther et al. 2011; van Olphen et al. 2009). Importantly, studies comparing outcomes among men and women also found that when formerly incarcerated women could not find employment, their families were less likely than those of men to provide financial and other support—even though women had been more engaged in substance use treatment post-release (Lattimore et al. 2009; Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008). This differential level of family support noted between men and women upon release from prison may also contribute to the higher prevalence of poor psychological outcomes for women following reentry into the community (Lattimore et al. 2009; Mallik-Kane and Visher 2008).

TANF, Criminal History, and Health as Employment Barriers

Given its programmatic focus on providing economic support and job search services, TANF could play an important role in mitigating the negative impacts of a criminal record on both employment and health for disadvantaged women. However, none of the studies in the review considered receiving TANF as potentially moderating the effect of a criminal record history on either employment or health. Of the seven studies that included TANF as a variable, in most receiving TANF was assessed primarily as a background or sample characteristic (Acs and Loprest 2003; Brock et al. 2002; Michalopoulos et al. 2003; Morgenstern et al. 2003; Quint et al. 1999). Thus, while these studies examined the extent to which health problems and criminal histories created employment barriers for TANF recipients (model 3.c, Figure 3), none conceptualized the potential cascade of events that a criminal record history could have on health via employment and/or receiving TANF.

One relatively stark finding that emerged from this group of studies was the wide variation in the estimated prevalence of criminal record histories among the TANF population. This is likely in part due to differences in using arrests, convictions, or incarcerations as an indicator of a “criminal background,” differences in state laws that bar individuals with select types of past convictions (most often drug-related) from receiving TANF support (Pogorzelski et al. 2005), and differences in criminal record histories in TANF subgroups. For example, one study found that about 6 percent of TANF recipients had a criminal conviction (Brock et al. 2002), while another found 56 percent and 25 percent of TANF recipients with substance abuse problems report ever being arrested or incarcerated, respectively (Morgenstern et al. 2003). Findings related to the extent to which a criminal record history is a barrier to employment were equivocal. One study documented no significant differences in employment between women on TANF with and without a criminal conviction (Acs and Loprest 2003). Another study conducted roughly during the same period of time, however, found TANF recipients with a criminal conviction were almost twice as likely to be unemployed (Brock et al. 2002).

Along with these studies of TANF recipients, additional studies in the review highlighted that, despite the fact that women leaving jails and prisons assert that they will need financial support, few used TANF. Although nearly 25 percent of offenders said that they expected to use “public assistance” upon release, only 5.9 percent were receiving aid 1 month post-release (Visher et al. 2004). Qualitative interviews with women leaving prison suggested that reasons for this difference in seeking access to and receipt of public assistance benefits may have been due to women’s fear of stigma during the TANF application process, their unwillingness to involve another case manager in their lives, and the fact that parole guidelines require that they find work (Brown and Bloom 2009; Brown and Barbosa 2001).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research synthesis was to understand researchers’ conceptualizations of the relationships among: (1) a criminal conviction; the collateral consequences of restricted (2) employment and (3) receiving TANF that can occur following a criminal conviction; and (4) health among women. Given the literature showing that employment improves the lives of poor women, and the fact that TANF is the primary government program accessible to poor women that provides job training and placement services, we were particularly interested in determining whether any findings suggested that employment or TANF might mediate the negative consequences of criminal justice involvement on health.

Studies included in this research synthesis did yield several important findings. First, engagement with the criminal justice system (mainly incarceration) had significant and long-lasting detrimental manifestations on employment among women. Second, formerly incarcerated women had a high burden of poor health and faced a lack of services upon release. A major theme of the qualitative findings from women returning to their communities after incarceration was that not being able to secure employment was quickly associated with stress, hopelessness, and reports of feeling depressed. Third, although the TANF program could potentially link disadvantaged women with criminal convictions to employment, research in this area has been limited. However, a few studies did show that, along with laws prohibiting some women with convictions from receiving TANF, access was also limited by the stigma associated with the TANF program.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, it is possible that our search protocol could have missed some studies worthy of inclusion. To minimize this possibility, we searched multiple databases; included grey literature from organizations with long histories of conducting research in the areas of TANF, employment, and the criminal justice system; and incorporated multiple search terms to include as many relevant studies as possible. Second, we were only able to analyze articles published in English, although the fact that our study focused on articles about the U.S. criminal justice system made this less of a concern. Third, given the fact that we only included studies on women, the findings from this review may not be applicable to formerly incarcerated men.

From a public health perspective, the collateral consequences of criminal convictions are likely to be associated with critically important social determinants of health for women. Both a criminal conviction and the legally- and socially-imposed restrictions to TANF benefits are associated with employment opportunities available to disadvantaged women. The erosion of employment opportunities that occur as a consequence of a criminal record history have been well-documented among men—and are equally likely to influence the economic trajectory that women experience over the remainder of their lives. Moreover, although the majority of studies have focused on previously incarcerated individuals, some findings suggest any type of criminal record history results in employers being less willing to hire applicants (Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll 2003). Despite their clear potential theoretical significance, we find that relevant potentially causal pathways between employment- and TANF-related collateral consequences due to a criminal conviction and health are largely untested. Rather than using a causal framework to understand the extent to which criminal involvement may indirectly relate to health through its effects on employment and TANF, studies in this area have overwhelmingly solely provided descriptions of the health conditions, employment experiences, and TANF use among those who have been incarcerated.

To understand better these potential pathways, future research in this area should focus on the role of public benefit programs, such as TANF, as well as employment, in mediating or moderating the indirect relationship between criminal convictions on health. Researchers should also give more consideration to the importance criminal convictions, which do not necessarily result in incarceration, could have for women’s health in particular. Approximately 63 percent of the studies in this synthesis focused on formerly incarcerated populations, despite the fact that only a minority of people involved in the criminal justice system is ever incarcerated (Boruchowitz, Brink, and Dimino 2009), and that employment-related collateral consequences occur, regardless of whether an individual’s arrest or conviction of a crime leads to incarceration (Boruchowitz, Brink, and Dimino 2009; Rodriguez and Emsellem 2011). Thus, the effects of collateral consequences as social determinants of health may be vastly underestimated.

Building on the findings from this research synthesis, future research should examine the extent to which the type of offense, severity of the crime, and/or sentences served (i.e., incarceration versus community service) influence receiving TANF, employment trajectories, and health outcomes for women. Additionally, more studies are needed that move from simply describing the associations between criminal justice system involvement, health, employment, and TANF use to examining the causal pathways linking these important variables. And last, based on research showing that criminal convictions may be particularly damaging to the employment prospects of African American men (Pager 2003; Pager, Western, and Sugie 2009) and that TANF programs with more African American women on the caseloads are more stringent (Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011), future studies should explicitly test whether these causal pathways differ based on race/ethnicity. It is only through increasing our knowledge of these interconnections that we can begin to design public health interventions and public policies to address this as a potential ‘root cause’ of health disparities among women in the U.S.

Contributor Information

Amanda Sheely, Department of Social Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, Phone: 44 (0)20 7405 7686, a.sheely@lse.ac.uk.

Shawn M. Kneipp, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Nursing, Carrington Hall CB #7460, Office #5104, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7460, Phone: 919-966-5425, Fax: 919-966-7298, skneipp@email.unc.edu.

References

- Acs G, Loprest P. A study of the District of Columbia’s TANF caseload. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association. ABA standards for criminal justice: Collateral sanctions and discretionary disqualification of convicted persons. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arditti JA, Few AL. Mothers’ reentry into family life following incarceration. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2006;17:103–23. doi: 10.1177/0887403405282450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti J, Few A. Maternal distress and women’s reentry into family and community life. Family Process. 2008;47(3):303–21. doi: 10.1111/famp.2008.47.issue-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: An agenda for further research and action. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2012;89(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Women offenders and the gendered effects of public policy. Review of Policy Research. 2004;21(1):31–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00056.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Owen B, Covington S. Gender-responsive strategies for women offenders: A summary of research, practice, and guiding principles for women offenders. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boruchowitz RC, Brink MN, Dimino M. Minor crimes, massive waste: The terrible toll of America’s broken misdemeanor courts. Washington, DC: National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brock T, Coulton C, London A, Polit D, Richburg-Hayes L, Scott E, Verma N. Welfare reform in Cleveland: Implementation, effects, and experiences of poor families and neighborhoods. New York: MDRC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Bloom B. Reentry and renegotiating motherhood: Maternal identity and success on parole. Crime & Delinquency. 2009;55(2):313–36. doi: 10.1177/0011128708330627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SG, Barbosa G. Nothing is going to stop me now: Obstacles perceived by low-income women as they become self-sufficient. Public Health Nursing. 2001;18(5):364–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Proctor A. Intersections of race, class, gender, and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Feminist Criminology. 2006;1:27–47. doi: 10.1177/1557085105282899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burris S. Introduction: Merging law, human rights, and social epidemiology. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2002;30(4):498–509. doi: 10.1111/jlme.2002.30.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin G. Race, the war on drugs, and the collateral consequences of criminal conviction. Journal of Gender, Race & Justice. 2002;6:253–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. Research synthesis and meta-analysis. 4. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons and the health of urban populations: A review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2001;78(2):214–35. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze L. Correctional population in the United States, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glaze LE, Maruschak LM. Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Almeida DM, Neupert SD, Ettner SL. Socioeconomic status and health: A micro-level analysis of exposure and vulnerability to daily stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45(1):1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrun K, Dematteo D, Fretz R, Erickson J, Yasuhara K, Anumba N. How “specific” are gender-specific rehabilitation needs? An empirical analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(11):1382–97. doi: 10.1177/0093854808323678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Raphael S, Stoll MA. Employer demand for ex-offenders: Recent evidence from Los Angeles. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- La Vigne NG, Brooks LE, Shollenberger TL. Women on the outside: Understanding the experiences of female prisoners returning to Houston, Texas. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore PK, Visher CA. The multi-site evaluation of SVORI: Summary and synthesis. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luther JB, Reichert ES, Holloway ED, Roth AM, Aalsma MC. An exploration of community reentry needs and services for prisoners: A focus on care to limit return to high-risk behavior. Aids Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(8):475–81. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik-Kane K, Visher C. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L, Parks E. Probation and parole in the United States, 2011. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos C, Edin K, Fink B, Landriscina M, Polit D, Polyne J, Richburg-Hayes L, Seith D, Verma N. Welfare reform in Philadelphia: Implementation, effects, and experiences of poor families and neighborhoods. New York: MDRC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, McCrady BS, Blanchard KA, McVeigh KH, Riordan A, Irwin TW. Barriers to employability among substance dependent and nonsubstance-affected women on federal welfare: Implications for program design. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(2):239–46. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108(5):937–75. doi: 10.1086/374403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Western B, Sugie N. Sequencing disadvantage: Barriers to employment facing young black and white men with criminal records. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;623(1):195–213. doi: 10.1177/0002716208330793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinard M. Collateral consequences of criminal convictions: Confronting issues of race and dignity. NYUL Review. 2010;457:459–534. [Google Scholar]

- Pogorzelski W, Wolff N, Pan K-Y, Blitz CL. Behavioral health problems, ex-offender reentry policies, and the “Second Chance Act”. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(10):1718–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint J, Edin K, Buck ML, Fink B, Padilla YC, Simmons-Hewitt O, Valmont ME. Big cities and welfare reform: Early implementation and ethnographic findings from the project on devolution and urban change. New York: MDRC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MN, Emsellem M. 65 million “need not apply:” The case for reforming criminal background checks for employment. New York: National Employment Law Project; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(6):840–54. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda S, Chambers L, Wilson M, Mustard C, Rourke SB, Bayoumi A, Raboud J, Lavis J. Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):541–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soss J, Fording RC, Schram SF. Disciplining the poor: The persistent power of race. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Steffensmeier D. The nature of female offending: Patterns and explanation. In: Zaplin R, editor. Female offenders: Critical perspectives and effective interventions. 2. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2007. pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- United States Sentencing Commission. 2010 sourcebook of federal sentencing statistics. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N, Barnes M. Nowhere to go: How stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy. 2009;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visher C, Kachnowski V, La Vigne N, Travis J. Baltimore prisoners’ experiences returning home. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- White House Council on Women and Girls. Women in America: Indicators of social and economic well-being. Washington, DC: United States Executive Office of the President; 2011. [Google Scholar]