Abstract

Active intracellular transport is a central mechanism in cell biology, directed by a limited set of naturally occurring signaling peptides. Here we report the first non-peptide moiety that recruits intracellular transport machinery for nuclear targeting. Proteins synthetically modified with a simple aromatic boronate motif are actively trafficked to the nucleus via the importin α/β pathway. Significantly, proteins too large to passively diffuse through nuclear pores were readily imported into the nucleus through this boronate-mediated pathway. The use of this simple motif to provide active intracellular targeting provides a promising strategy for directing subcellular localization for therapeutic and fundamental applications.

Introduction

Intracellular targeting has the same potential as cellular targeting to increase therapeutic efficacy while reducing off-target effects.1,2 In biology, 3 this targeting process relies on specific peptide signals that interact with sorting factors and/or organelle receptors to guide proteins to their final destination.4 Intracellular targeting of proteins can occur through two mechanisms: passive diffusion and active transport.5 Localization through passive diffusion is based on the affinity of the protein for structural features present in the organelle, and is energy independent. In contrast, active transport of proteins uses energy to move against the concentration gradient.5,6 Active transport is highly efficient, and is widely employed in cells for translocation of proteins to cellular organelles including the nucleus,7 mitochondria,8 endoplasmic reticulum9 and peroxisome.10

The vast majority of systems used by scientists for intracellular targeting of proteins and synthetic payloads prefer peptide localization signal.11 Currently, there are few non-peptidic signals for subcellular localization of biomacromolecules. The most widely recognized example is the triphenylphosphonium (TPP) group, where localization is driven by the high potential of the mitochondrial membrane.12 More recently, Ishida et al. have developed a versatile strategy for intracellular targeting by conjugating ligands with affinity to structural motifs found in different organelles. As an example, conjugation of a DNA binding dye provided localization of a small protein (GFP) to the nucleus.13 All of the above non-peptidic systems, however, utilize a passive diffusion mechanism that is less efficient and versatile than active transport processes.

We report here that a simple benzylboronate chemical motif provides highly efficient active targeting of proteins to the nucleus. This represents, to our knowledge, the first fully synthetic intracellular targeting motif that accesses an active transport mechanism. Proteins modified with this nuclear boronate label, including fluorescent proteins, ribonuclease A (RNase A) and chymotrypsin were rapidly and efficiently transported to the nucleus by the importin α/β pathway, presenting a simple and effective strategy for targeting of proteins to the nucleus, an emerging strategy for increasing the efficacy of therapeutic regimens.2

Results and Discussion

There are two key challenges for achieving active subcellular targeting of proteins. The first task is delivery of the protein into the cytosol,14 enabling access to cellular transport machinery. This goal was achieved using the HKRK nanoparticle-stabilized capsule (NPSC) platform that provides direct delivery of negatively charged proteins to the cytosol.15–16,17 The second challenge is accessing active transport mechanisms once inside the cell. When we employed NPSCs to deliver benzyl boronate-modified proteins, 18 we fortuitously discovered that the modified proteins rapidly accumulated in the nucleus, providing a remarkably simple strategy for nuclear targeting (Figure 1 and Figure S1).

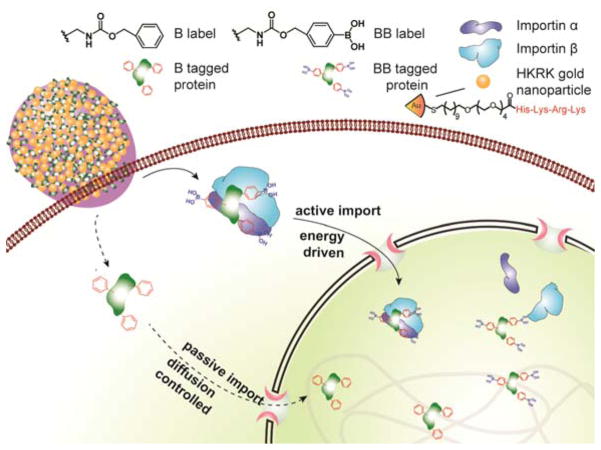

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing delivery of proteins tagged with benzylboronate complex to the cytosol followed by translation to the nucleus using active transport with boronate ligands and through passive diffusion using non-boronate analogs.

The benzyl boronate tag drives nuclear accumulation

Demonstration of nuclear localization through boronate tagging was obtained through conjugation of the benzyl boronate tag to eGFP (eGFP-BB; Figure 2a, Figure S2 and Movie S1). We used eGFP modified with three BB tags; greater functionalization resulted in insoluble aggregates. eGFP was chosen for two reasons: (i) The fluorescence of eGFP depends on the conformation and integrity of the protein; structural change or degradation of eGFP therefore results in substantial fluorescence loss,19 (ii) eGFP does not interfere or interact with the nuclear importing machinery inside cells.20

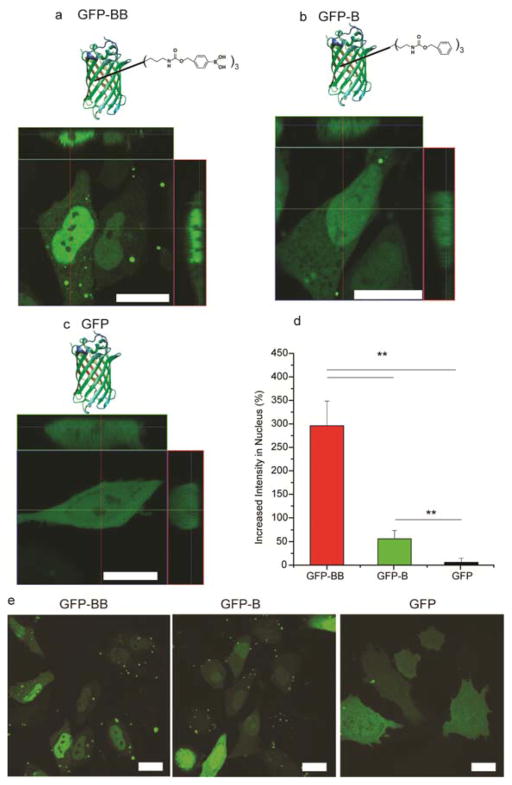

Figure 2.

Nuclear accumulation of eGFP relies on the BB label. (a) LSCM image of a HeLa cell after the delivery of eGFP-BB. (b) LSCM image of a HeLa cell after the delivery of eGFP-B. (c) LSCM image of a HeLa cell after the delivery of normal eGFP. Scale bars: 20 μm. (d) Quantitative analysis of the increased fluorescence intensity of eGFP in the nucleus. Six random cells representing different intensities were analyzed in each group. ** indicates p value of t-test less than 0.01. (e) Large scale LSCM images of HeLa cells after delivery of eGFP with different labels. Native eGFP was delivered as a control. Scale bars: 20 μm.

One hour after delivery, eGFP-BB was highly localized in the nucleus (Figure 2a and 2e). Quantitative analysis of the LSCM image revealed that the average concentration of eGFP-BB was 300% ± 50% higher in the nucleus than in the cytosol (Figure S3a and Table S1). In direct contrast, unmodified eGFP is homogeneously distributed throughout the cell and nucleus (Figure 2c).15 The targeting observed with our system was significantly more efficient than any observed in our prior studies of NPSC delivery of eGFP engineered with peptide nuclear localization signals (NLS):21 the boronate tag provides ~2-fold better localization than the best NLS in the study (c-Myc).

Preliminary structure-activity studies were used to identify the features of boronate conjugation that facilitate nuclear targeting of proteins. An additional protein, non-boronated benzyl modified eGFP (eGFP-B) was generated: (Figure 2b, 2e) LSCM image showed enhanced nuclear accumulation of B conjugates (60% ± 20%), albeit with lower efficiency than observed with BB (300%). (Figure S3 and Tables S2, S3). These results indicate that the boronate moiety is the key component driving nuclear transport, with some synergy observed with aromatic functionality.

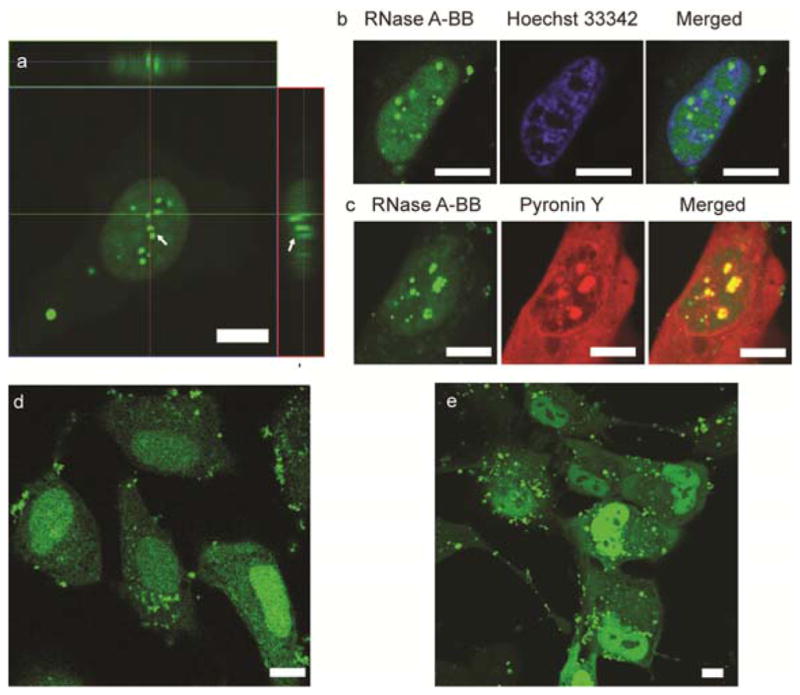

Boronate-based targeting is a versatile platform for nuclear localization of proteins. In addition to GFP, we delivered RNase A and homologues have therapeutic potential for diseases in diseases including cancer22 and AIDS.23,24 For our studies, RNase A was first modified through conjugation with seven BB moieties (Figure S4), followed by fluorescein modification to track the delivery process. NPSCs efficiently delivered boronate-modified RNase A into HeLa cells (Figure 3a and Figure S5a) with a high degree of nuclear localization, with an aconitic acid-modified control showing only limited nuclear enrichment (Figure S5b). DNA and RNA staining showed that the regions of greatest accumulation of RNase were, as expected, condensed nuclear RNAs (Figures 3b, 3c and Figure S6). Boronate targeting can also be used to deliver proteins that would otherwise not be found in the nucleus: benzyl boronate-conjugated chymotrypsin was likewise effectively delivered to the nucleus (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Delivery of RNase A-BB and eGFP-BB into HeLa cells and MSCs respectively using the NPSC delivery platform. (a) LSCM image showing RNase A-BB delivery into HeLa cells by NPSCs. Arrows indicate granular structures of RNase A-BB formed in the nucleus. (b) Colocalization of RNase A-BB with Hoechst 33342, a DNA staining dye. (c) Colocalization of RNase A-BB with Pyronin Y, a dsRNA staining dye. (d) LSCM image showing chymotrypsin-BB delivery into HeLa cells by NPSCs. (e) LSCM images of MSCs after delivery of GFP-BB. Scale bars: 10 μm.

The potential utility of boronate-mediated nuclear targeting was provided by delivery to mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), a cell type with high potential in clinical25 use that is often prepared for use ex vivo. As expected, obvious nuclear accumulation of eGFP-BB was observed after 1 hr delivery (Figure 3e and Figure S9).

BB targets the nucleus through both active and passive mechanisms

Nuclear accumulation of proteins can be mediated by either active import or passive diffusion. To determine if active transport was operative, we treated HeLa cells with ivermectin.26 –27,28,29 Active transport of protein in nucleus is energy dependent and is regulated by the importin α/β pathway. Ivermectin is a specific inhibitor of this pathway 26–29 that does not affect other nuclear transport pathways such as nuclear envelope-embedded nuclear pore complexes (NPCs, passive diffusion).26 Delivery of eGFP-BB NPSCs in ivermectin-treated cells showed nuclear accumulation of protein (Figures 4a, 4b), however the enhancement of nuclear localization decreased dramatically from ~300% to 60% ± 30% (Figure 4g, Figure S7a and Table S4). This result indicated that active transport of protein through the importin α/β pathway was inhibited by ivermectin, while passive diffusion of protein through the NPC was not affected. Therefore, these studies indicate that active transport of protein via importin α/β pathway was responsible for the majority of the nuclear localization observed with BB tagged proteins. To test whether other active import pathways are involved in the nuclear accumulation of eGFP-BB, we depleted ATP from HeLa cells before and during delivery. ATP is a prerequisite for both importin-dependent30 and other31 pathways. One hour after delivery in the ATP depleted condition, nuclear accumulation was observed (Figure 4c). Fluorescence intensity enhancement in the nucleus was 95% ± 20% (Figure 4g, Figure S7b and Table S5), similar to that achieved after ivermectin treatment, indicating that importin was the major driver of active transport.

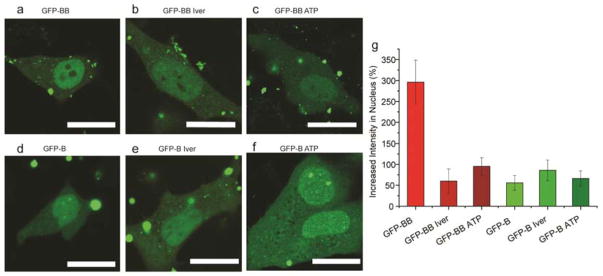

Figure 4.

Inhibition of active import to nucleus significantly reduces nuclear accumulation of boronate-tagged eGFP. (a) eGFP-BB delivery before and (b) after inhibition of importin α/β pathway. (c) eGFP-BB delivery after inhibition of all active import pathway by ATP depletion. (d) eGFP-B delivery before and (e) after inhibition of importin α/β pathway. (f) eGFP-B delivery after inhibition of all active import pathway by ATP depletion. Scale bars: 20 μm. (g) Quantitative analysis of increased fluorescence intensity of eGFP-BB and eGFP-B in the nucleus after delivery with or without pretreatment using six cells in each group.

A similar efficiency of nuclear localization was observed with importin inhibition and the non-boronate B system, suggesting a passive mechanism dependent on the aromatic substitution. To test this hypothesis, we delivered eGFP-B into HeLa cells either in the presence of ivermectin (Figure 4d, 4e) or under ATP depletion (Figure 4f). As expected, modest nuclear accumulation of eGFP-B was observed in both conditions (Figure 4g, Figure S7c, S7d and Tables S6, S7). These results corroborate our observation that the benzene ring is involved in nuclear accumulation, with localization potentially arising from hydrophobic interactions mediated by the externally-presented aromatic substituents18 analogous to passive nuclear localization during viral infection.32

Active targeting provides delivery of large proteins to the nucleus

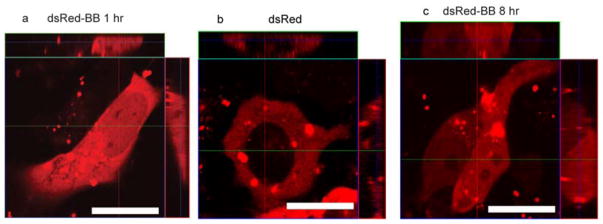

Proteins with molecular weight greater than 60 kD cannot passively diffuse through the nuclear pore, and hence require active targeting to access the nucleus.33 We employed dsRed, a tetramer fluorescent protein with a Mw of 112 kD (Figure 9a and 9b) that has only been delivered to the nucleus through use of nuclear localization signals.34 After 1 hr of incubation, dsRed labeled with BB tag (dsRed-BB) was strongly accumulated in the nucleus (Figure 5a and Figure S8c). As expected, no dsRed was observed in nucleus without the boronate tag (Figure 5b and Figure S8d). After 8 hr culture, obvious nuclear localization of dsRed-BB in HeLa cell was still observed (Figure 5c). Together these results substantiate an active import mechanism of benzyl boronate tagged proteins

Figure 5.

Large fluorescent protein dsRed accumulated in the nucleus after labeling with BB tag. (a) deRed-BB accessed nucleus of HeLa cell after 1 hr delivery. (b) dsRed without BB tag did not enter nucleus of HeLa cell after 1 hr delivery. (c) 8 hr after dsRed-BB delivery to HeLa cells. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Conclusions

In summary, we describe the use of benzyl boronic acids for synergistic active and passive targeting of proteins for delivery to the nucleus. Our mechanistic experiments show that the boronic acid moiety mediates active nuclear import, enabling both efficient transport to the nucleus and access of payloads too large for passive targeting strategies to be utilized. The boronate targeting strategy provides an unprecedented, completely synthetic strategy for nuclear targeting. The boronate moiety is minimally perturbing, and can be engineered to be either permanent or cleavable, providing further versatility.18 In a broader context, the use of simple chemical moieties to achieve nuclear targeting opens up new strategies for precision delivery of proteins to the nucleus, decreasing off-target effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH GM077173 and EB022641 (VR), and the NSF: CAREER Award (Grant No. DMR1452122) (QX) and CHE-1506725 (VR).

Footnotes

Author contributions

R.T. and M.W. contributed equally to this work. R.T. and V.M.R. designed the delivery and localization procedures. M.W. and Q.X. designed and synthesized the chemical signals. M.W. modified and characterized the proteins. MR expressed the recombinant protein. R.T., M.R. and Y.J. performed the delivery experiment. Z.J. and M.R. synthesized AuNPs. R.T. and M.R. analyzed the images. The manuscript was written by R.T., M.R., M.W., Q.X. and V.M.R. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Experimental Sections, Figures S1–S9, Tables S1–S7 and Supplementary movie, S1 (AVI)

References

- 1.Rajendran L, Knolker HJ, Simons K. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:29–42. doi: 10.1038/nrd2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakhrani NM, Padh H. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2013;7:585–599. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S45614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung MC, Link W. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3381–3392. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicks SW, Galan JE. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:316–326. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freitas N, Cunha C. Curr Genomics. 2009;10:550–557. doi: 10.2174/138920209789503941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehling P, Brandner K, Pfanner N. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:519–530. doi: 10.1038/nrm1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwoebel ED, Ho TH, Moore MS. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:963–974. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harbauer AB, Zahedi RP, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Cell Metab. 2014;19:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann R, Eyrisch S, Ahmad M, Helms V. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:912–924. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platta HW, Erdmann R. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2811–2819. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair R, Carter P, Rost B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:397–399. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhopadhyay A, Weiner H. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2007;59:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida M, Watanabe H, Takigawa K, Kurishita Y, Oki C, Nakamura A, Hamachi I, Tsukiji S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12684–12689. doi: 10.1021/ja4046907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu AL, Tang R, Hardie J, Farkas ME, Rotello VM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:1602–1608. doi: 10.1021/bc500320j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang R, Kim CS, Solfiell DJ, Rana S, Mout R, Velazquez-Delgado EM, Chompoosor A, Jeong Y, Yan B, Zhu ZJ, Kim C, Hardy JA, Rotello VM. ACS Nano. 2013;7:6667–6673. doi: 10.1021/nn402753y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang R, Jiang Z, Ray M, Hou S, Rotello VM. Nanoscale. 2016;8:18038–18041. doi: 10.1039/c6nr07162g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeh YC, Tang R, Mout R, Jeong Y, Rotello VM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5137–5141. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M, Sun S, Neufeld CI, Perez-Ramirez B, Xu QB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:13444–13448. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corish P, Tyler-Smith C. Protein Eng. 1999;12:1035–1040. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.12.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto Y, Saiwaki T, Yamashita J, Yasuda Y, Kotera I, Shibata S, Shigeta M, Hiraoka Y, Haraguchi T, Yoneda Y. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:617–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray M, Tang R, Jiang ZW, Rotello VM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015;26:1004–1007. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borriello M, Laccetti P, Terrazzano G, D’Alessio G, De Lorenzo C. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1716–1723. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turcotte RF, Raines RT. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:1357–1363. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch M, Benito A, Ribo M, Puig T, Beaumelle B, Vilanova M. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2167–2177. doi: 10.1021/bi035729+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:126–131. doi: 10.1038/nrm3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagstaff KM, Rawlinson SM, Hearps AC, Jans DA. J Biomol Screen. 2011;16:192–200. doi: 10.1177/1087057110390360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosyna Friederike K, Nagel M, Kluxen L, Kraushaar K, Depping R. Biol Chem. 2015;396:1357–1367. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2015-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwao C, Shidoji Y. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4419. doi: 10.1038/srep04419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundberg L, Pinkham C, Baer A, Amaya M, Narayanan A, Wagstaff KM, Jans DA, Kehn-Hall K. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kose S, Imamoto N, Yoneda Y. FEBS Lett. 1999;463:327–330. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu M, Zak J, Chen SO, Sanchez-Pulido L, Severson DT, Endicott J, Ponting CP, Schofield CJ, Lu X. Cell. 2014;157:1130–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onder Z, Moroianu J. Virology. 2014;449:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dingwall C, Laskey RA. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1986;2:367–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodrigues F, van Hemert M, Steensma HY, Corte-Real M, Leao C. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3791–3794. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3791-3794.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.