Abstract

Low back pain in children and adolescents are usually attributed to mechanical causes and faulty positions. Although most of them are self-limiting, physicians should be aware of the red flag signs that warrant complete evaluation to rule out malignant causes of back pain. As delay in the diagnosis of vertebral lytic lesion may have sequelae in the growing children, pain disproportionate to the signs should have low threshold levels for evaluation. We report a case of 6-year-old boy who presented with worsening back pain. Initially evaluated for tuberculosis spine, he was diagnosed to have Langerhans cell histiocytosis of spine. He improved symptomatically with chemotherapy and spine orthosis and is in complete remission now.

Keywords: Back pain, children, Langerhans cell histiocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain in the pediatric population is a common complaint with wide differentials including mechanical, amplified musculoskeletal pain, infectious, inflammatory, and malignancy. Vertebral and spinal neoplasms are rare in children and typically present with persistent and localized back pain that is worse at night, constant and symptoms lasting less than 3 months.[1] Transient joint and limb pain is common among children, and in majority of cases resolves without any treatment. However, pain disproportionate to physical findings and not alleviated by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, strongly suggest the presence of a serious underlying pathology.

We present a case of a 6-year-old boy who presented with back pain and found to have Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) of the spine.

CASE REPORT

A 6-year-old boy presented with a history of lower back pain for the past 10 days with worsening of symptoms at night time, disturbing his sleep, and restricting his normal activities and play. He gave a history of a trivial fall on the back at the school, a few days before presentation. He had no other constitutional symptoms. The child was initially managed with local analgesic creams and massage therapy. He was later taken to family physician who had advised symptomatic therapy attributing it to mechanical and postural causes. However, in view of worsening of pain, the child was evaluated for tuberculosis spine. On examination, child had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. On local examination, there was tenderness over the lumbar spine. Antalgic gait and scoliosis were present. The rest of the musculoskeletal system and neurological examination was normal.

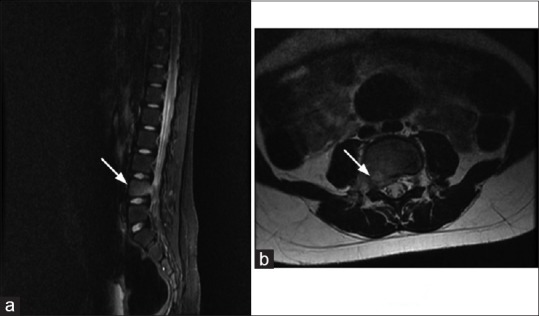

Blood investigations revealed normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-Reactive protein. Chest X-ray showed normal lung and Mantoux and sputum for Acid-Fast Bacilli was negative. The spine X-ray showed collapse of L4 vertebral body. With a provisional diagnosis of infective spondylitis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) spine done showed a lesion involving the right side of the L4 vertebral body and pedicle, with extension into the right L4–L5 neural foramen [Figure 1a and b]. Pediatric oncologist opinion was sought and advised biopsy of the lesion. Computed tomography-guided biopsy of L4 vertebra showed aggregates of eosinophils and histiocytes having nuclear grooving and there was no evidence of granulomas. By immunohistochemistry the lesional cells were diffusely positive for S100, vimentin and focally positive for CD68 and CD1a, confirming the diagnosis of LCH. The work up for diabetes insipidus was normal. Bone scan showed abnormal increased tracer uptake only in the region of body of L4 vertebra. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy to rule out marrow involvement was normal. He was started on LCH III protocol and brace application for spine stabilization.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Magnetic resonance imaging lumbosacral spine prechemotherapy: Saggital short T1 inversion recovery and axial T2 weighted sequence show mildly hyperintense lesion in the body and right pedicle of L4 vertebra, minimial soft tissue is seen in the adjacent epidural space and ipsilateral neural foramina, vertebral body height is maintained

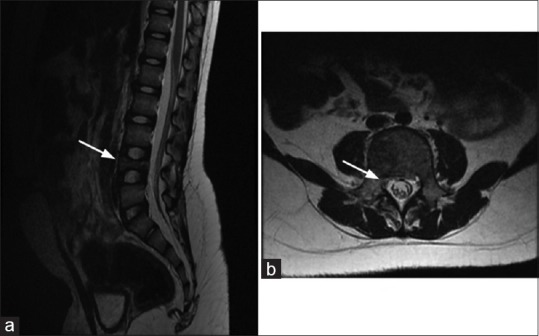

The pain disappeared within 2 weeks of chemotherapy. MRI lumbosacral spine after 6 weeks of chemotherapy showed compression fracture of L4 vertebra with the lesion predominantly confined on the right side involving the pedicle and the lamina and no soft tissue involvement [Figure 2a and b]. The child had completed maintenance chemotherapy, is completely symptom-free now and has normal daily activities.

Figure 2.

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging lumbosacral spine: Saggital T2 weighted magnetic resonance showing moderate collapse of L4 vertebral body. (b) Magnetic resonance imaging lumbosacral spine: Axial T2 weighted post chemo images show complete resolution in the epidural soft tissue component

DISCUSSION

Low back pain is common in children and adolescents, which can arise from mechanical problems such as computer use, physical activity, and heavy backpacks. Fever and other constitutional symptoms occur in the presence of an infection or tumor. The red flag signs which warrant immediate evaluation are age less than 4 years, persistent nighttime pain, neurological symptoms, self-imposed activity limitations, and systemic symptoms.[1]

Regular pain that occurs at night and awakens the child is usually associated with infections such as osteomyelitis and discitis. Among neoplasms, benign neoplasms include osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, neurofibroma, and aneurysmal bone cyst. Malignancies include Ewing's sarcoma, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, astrocytoma, leukemia, LCH, and metastatic disease.[2]

LCH is a rare disease associated with a proliferation of Langerhans cells involving the reticuloendothelial system. Among bone tumors, LCH accounts for <1%, and up to 80% of these children will present before they reach the age of 10 years.[3] The most frequently affected site in children with LCH is the bone which is encountered in about 75%–80% of patients with LCH and may be the only affected site, especially in children older than 5 years of age.[4] The most frequent sites of skeletal lesions are the skull, femur, mandible, pelvis, and spine. The incidence of spinal involvement varies from 6.5% to 25% in LCH of the bone.[5] Garg et al. have reported 45% lesions in the cervical spine; 32% in the thoracic spine; and 23% in the lumbar spine.[6] Children with only skeletal lesions have been found to have a good prognosis when compared to children with systemic involvement.[7]

In the vertebral body, LCH of spine appears as an osteolytic lesion called the vertebra plana. The incidence of soft tissue extension in children with LCH of the spine is about 50%. Back or neck pain was the most common presenting symptom and was the only presenting symptom in seventeen of the patients reported by Garg et al. Torticollis and abnormal gait were the additional symptoms reported.[6]

Evaluation includes complete blood count, liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, coagulation studies, measurement of urine osmolality, chest radiograph, ultrasonography of the liver and spleen, skeletal survey or bone scan, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy and MRI spine to rule out soft tissue involvement. Vertebral collapse, maintenance of disc spaces, lack of extraspinal spread, and lack of a soft tissue mass are the classic radiographic findings.

Patients with cervical and lumbar lesions have multilevel disease.[6] Hence, a technetium bone scan or a skeletal survey should be performed in such cases to rule out multiple skeletal lesions.

Spinal stability, preservation of neurological function, and eradication of the lesion are the goals of treatment. Spinal orthoses is recommended to support any spinal instability following the biopsy until sufficient reconstitution has occurred to restore stability. Chemotherapy itself rapidly reduces the intraspinal soft tissue mass and relieves the local and radicular pain even in patients with spinal cord and nerve root compression.[5]

The indications for spinal surgery are stabilization of an unstable segment of the spine that cannot be stabilized with an orthosis and neurological symptoms caused by compression of the spinal cord by the collapsed vertebra.[6]

CONCLUSION

A child presenting with persistent and progressive back pain should be evaluated extensively even if it is not associated with any other constitutional symptoms to rule out rare causes of vertebral lytic lesions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein RM, Cozen H. Evaluation of back pain in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1669–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman DS, Straight JJ, Badra MI, Mohaideen A, Madan SS. Evaluation of an algorithmic approach to pediatric back pain. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:353–7. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000214928.25809.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CW, Jarvis JG, Letts M, Carpenter B. Treatment and outcome of vertebral Langerhans cell histiocytosis at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Can J Surg. 2005;48:230–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khung S, Budzik JF, Amzallag-Bellenger E, Lambilliote A, Soto Ares G, Cotten A, et al. Skeletal involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Insights Imaging. 2013;4:569–79. doi: 10.1007/s13244-013-0271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng XS, Pan T, Chen LY, Huang G, Wang J. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the spine in children with soft tissue extension and chemotherapy. Int Orthop. 2009;33:731–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0529-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg S, Mehta S, Dormans JP. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the spine in children. Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1740–50. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200408000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanem I, Tolo VT, D’Ambra P, Malogalowkin MH. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:124–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]