Abstract

Background:

Tobacco use can alone lead to death worldwide, especially in developing and underdeveloped countries. China and Brazil are the world's largest producer of tobacco. India holds the third place in producing, and it is the fourth largest consumer of tobacco and its products in the world.

Objectives:

A case–control study was carried out to assess the influence of risk factors on patients with potentially malignant disorders (PMD) and oral cancer.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty cases diagnosed with PMD and oral cancer patients were selected for the study. An equal number 50 healthy controls who were also selected after age and gender matching. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the suspected risk factors for PMD and oral cancers. Chi-square test, Adjusted odd's ratios with 95% confidence interval were also used for the statistical analysis.

Results:

There is a statistically significant difference between the different age group, duration, frequency, exposure time, and synergistic effect of tobacco chewing, smoking and alcohol drinking.

Conclusions:

Chewing tobacco is one of the major risk factors in the initiation of PMD which can lead to oral cancer.

Keywords: Oral cancer, potentially malignant disorders, tobacco/betel quid

INTRODUCTION

In India, tobacco chewing, smoking and alcoholic consumption have become common social habits. It has been observed that there is a positive correlation with oral submucous fibrosis, oral leukoplakia and oral lichen planus which has potential for malignant transformation into oral cancer.[1,2,3] To reflect their widespread anatomical distribution’ recently, theWorld Health Organization termed a new name for all precancerous lesions and conditions as “potentially malignant disorders (PMD).”[4,5]

Tobacco/betel quid can alone lead to death worldwide especially in developing and underdeveloped countries. It is estimated that 5 million deaths were occurred worldwide in 2005 and by 2020, it is expected a rise in 10 million deaths annually. China and Brazil are the world's largest producer of tobacco. India holds the third place in producing and it is the fourth largest consumer of tobacco and its products in the world.[6] It has been proved that the synergistic effect on the carcinogenic potency of tobacco use in oral cancer by alcohol consumption is well documented.[7,8,9]

It is estimated that nearly 250 million tobacco users in India who account for about 19% of the world's total 1.3 billion tobacco/betel quid users.[6,10,11] Among school-going children, current tobacco users may vary from 2.7% in Himachal Pradesh to 63% in Nagaland. The prevalence of all types of tobacco use among men is about 47% (11%–79% in different states), and among women, smokeless tobacco use varies between 0.2% in Punjab and 61% in Mizoram.[6] In India, the age-standardized incidence rates per 1,00,000 populations were estimated to be 7.5 in women and 12.8 in men and it is in highest rate when compared to rest of the world. In India, there are 75,000 ± 80,000 new cases of oral cancer each year.[11]

It is noticed that approximately 50% was the 5-year survival rate for oral cancer for the past several decades very few has been conducted to correlate the relationship between specific risk factors influencing the PMD and oral cancer. Hence, this case–control study was carried out to analyze the influence of risk factors on patients with PMD and oral cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A case–control study was carried out to assess the influence of various risk factors among PMD and oral cancer patients. Patients with clinically diagnosed and histopathologically confirmed PMD and oral cancer patients were selected for the study. Necessary ethical approval was obtained from the higher authorities.

Fifty patients suffering from PMD and oral cancers were selected during the study period and all these patients were confirmed by histopathological examination. Treated patients/undergoing treatment for the PMD and oral cancers are excluded out of the study. An equal number, fifty healthy controls who were age- and sex-matched as par with the cases were also included for the study. In local language, the objectives of the study were explained to all the cases and controls and an informed consent was obtained. The data were collected in a specially designed pro forma with all relevant information like patient's age, gender, education, occupation, family's monthly income, quantity and duration of smoking, alcohol drinking and tobacco chewing habits.

The patients’ age was grouped into 10-year age intervals up to age 70 to analyze the decade-wise prevalence of PMD and oral cancer. Income was graded “low”, if it was <Rs. 1500, “low to medium” between Rs. 1500 and 3,000 and “medium to high” for income more than Rs. 3000 per month.[12] The education of the patient was categorized into illiterate or literate and if literate, the level of education further categorized into primary, middle, secondary, 12th and degree.

A socioeconomic status index (SES Index) was created based on the Hollingshead two-factor index[13] using education and occupation. The SES index was estimated using the formula; SES index = (Education × 3) + (Occupation × 5). The minimum value of the SES index was 8 for a subject who has a manual occupation and is in the education category non and illiterate. The maximum value of the SES index was 44 for a subject who has a professional/business occupation and professional education. The SES index was categorized into quartiles: 1–14, 15–19, 20–25 and ≥26.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the suspected risk factors for PMD and oral cancers. Chi-square test, Adjusted odd's ratios with 95% confidence interval were also used for the statistical analysis.[14] The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A) was used for the statistical analysis and the significance level was set at P < 0.05

RESULTS

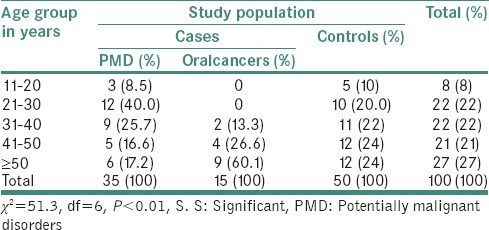

Table 1 shows the age-wise distribution of study population suffered from PMD and oral cancer. It was noticed that 40.0% of the study population in 21–30 years of age and 25.7% in 41–50 years of age suffered from PMD as compared to oral cancer. 60.1% were seen in more than 50 years of ageand 26.6% of population were in 41–50 years of age groups (P < 0.01, S). Statistically significant difference has been observed between different age groups among study population.

Table 1.

Age-wise distribution of cases and control group

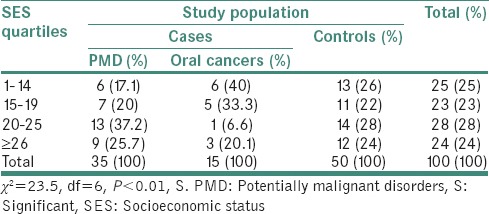

Table 2 shows the distribution of SES index and study subjects. In PMD, 37.2% of the population was in 20–25 SES quartiles, 17.1% and 20% of the study population were seen in 1–14 and 15–19 of SES index quartiles, respectively. Similarly, in oral cancer cases, 40% of populations were in 1–14 SES quartiles, 33.3% and 20.1% were observed in 15–19 and 20–25 SES quartiles, respectively. In control groups, 24% were in ≥26 SES and 28% and 22% in 20–25 and 15–19 SES quartiles, respectively. The results showed statistically significant difference in SES index and study population (P < 0.01, S).

Table 2.

Distribution of socioeconomic status index in cases with potentially malignant disorders, oral cancer and control group

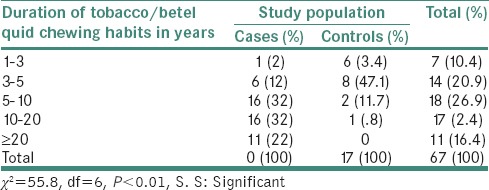

Table 3 shows that the duration of tobacco chewing habits among study population showed that the 32% of population chewed tobacco for 5–10 years, 32% and 22% chewed 10–20 and ≥20 years of duration, respectively. Whereas in controls, 47.1% chewed tobacco for 3–5 years and 35.4% chewed for 1–3 years of duration.(P < 0.01, S) Statistically significant difference was noticed between duration of tobacco chewing among the study population.

Table 3.

Distribution of duration of tobacco quid chewing habits among cases and controls

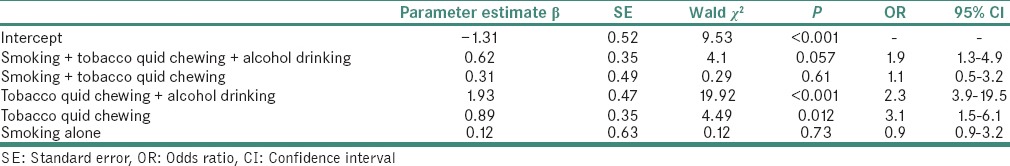

Table 4 showed that the occurrence of PMD among subjects with cigarette smoking, tobacco chewing and alcohol drinking was 1.9 times higher than nonchewers, nonsmokers and nondrinkers. Male subjects whose habits were limited to alcohol drinking and women were not entered to the model on risk analysis for PMD. Similarly, tobacco chewing and alcohol drinking have 2.3 times, and only tobacco quid chewing had 3.1 times higher occurrence of PMD than nonchewers, nonsmokers, nondrinkers also higher occurrence of PMD than nonchewers, nonsmokers and nondrinkers.

Table 4.

Synergistic effect of smoking, tobacco/betel quid chewing and alcohol drinking for potentially malignant disorders by logistic regression analysis risk factor

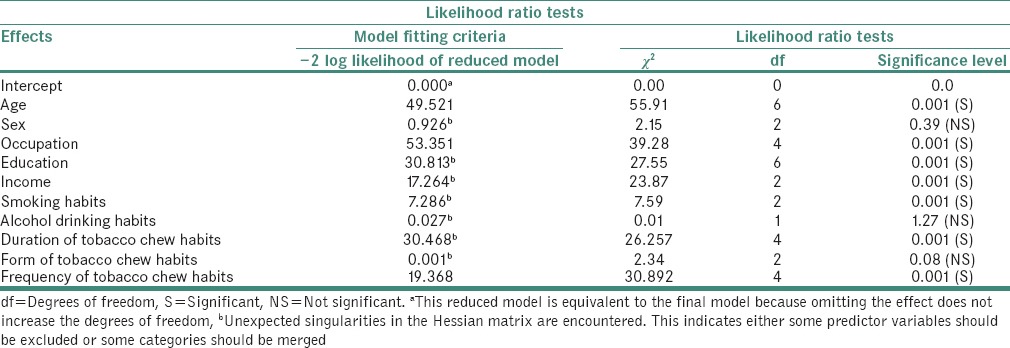

Table 5 showed the multiple logistic regression analysis for PMD and oral cancer showed that the most of the factors such as age, occupation, education, income, smoking habits, duration of tobacco quid chewing habits, frequency of tobacco chewing habits interacted and showed strong association in contributing the development of PMD and oral cancer.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of different variables in cases with potentially malignant disorders and oral cancers

DISCUSSION

In the world, one of the most life-threatening diseases is oral cancer. It is the sixth most common cancer in the world. The occurrence of oral cancer differs from age, lifestyle and their SES, and also, it varies from one country to another.[15,16,17] In the developed countries, cancer is the one of the comment cause of mortality, and it is 10th most common cause of mortality in developing countries. Oral cancer presents nearly 13% of all cancer.[18] over one-third of tobacco consumed is smokeless in South Asia. Traditional forms like tobacco with lime and betel quid are commonly used and it is increasing day-by-day not only among adults but also among teenagers and females. Various studies have been conducted in world which assessed the relationship between various risk factors in the development of oral cancer and PMD.[12,19,20,21,22]

In our study, we have analyzed the risk factors which had a key role in the development of oral cancer. The age range of occurrence of PMD in our study population was 11 to ≥50 years and 40% of PMD cases were seen in 21–30 years of age group. 26.6% to 60.1% of oral cancer cases were seen in age group of 31 to ≥50 years. Statistically significant difference was observed between PMD cases and oral cancer cases (P < 0.01, S). Several studies[19,22] showed that females were less affected as compared with males, these results are in consistent with our study results. It is noticed that 16–18 years in the mean age for starting of any habit and it the critical period for developing behaviors and responses.[18]

The PMD cases at an earlier age occurrence are more as compared to oral cancer and it may convert into oral cancer. It is also noticed that higher education and higher income was protective against PMD and oral cancer.[12,23] Statistically significant difference was observed between the study population and SES index (P < 0.01, S). The individuals with less education and low income were more likely to smoke cigarettes, chew tobacco and drink alcohol.[15,24] It is also observed that the excess mortality was observed for low SES in various studies.[16,18] These results are in concordance with our study results. The various lifestyle factors are affected by the SES which may alter the prevalence of oral cancer as well as PMD, including cigarette smoking, tobacco chewing and other bad habits. In our study, higher education, high income and higher SES index were all associated with a decreased risk of oral PMD and oral cancer.

It is scientifically proved that tobacco chewing habit triggers the changes which can lead to develop the PMD and oral cancer. Our study results were in concordance with the other studies conducted in the world.[20,25] Similarly in our results showed an odds of 33 times for developing PMD's in tobacco chewers versus nonchewers which is higher than the studies conducted in Srilanka by Ariyawardana et al.[22] and Chung et al.[26] which showed an odds of 16.2 and 8.4 times of developing the disease. This could be due to the differences in tobacco chewing habits practiced by study population and also method of chewing, their composition, which varies from one country to country. Similarly, for oral cancer cases, an odds of 19.5 times of developing oral cancer were observed between tobacco chewers as compared to nonchewers. These results were inconsistent with other studies conducted at various parts of India.[19,25] The occurrence of oral cancer is probably due to the constant contact of tobacco during chewing which releases carcinogens.[19] This carcinogenic process is multiple staged and the major effect of tobacco is in relatively early phase carcinogenesis.[24] In cases, 32% chewed tobacco/betel quid for 5–10 years and 10–20 years, respectively, followed by 22% cases for ≥20 years. Similarly, 47.1% and 35.4% of controls chewed tobacco for 3–5 and 1–3 years, respectively.

The multiple logistic regression analysis was done to check for the synergistic effect of tobacco chewing, smoking and alcohol drinking habits were analyzed for both PMD and oral cancer. The results showed synergism in the development of PMD and oral cancer. Synergistic effect ultimately is a collectively due to the combination of ingredients present in tobacco and other habits rather than just the presence of each one individually. The results showed that an odds of 1.9 and 2.3 times more of developing PMD, and oral cancer cases were observed for the combination of various risk factors. These results confirmed that there is some synergistic effect of risk factors alone or in combination in the occurrence of PMD and oral cancer. Lesser odds of 0.9 are observed for smoking alone in the development of PMD and oral cancer which indicates smoking habits alone cannot cause oral cancer but with a combination of other risk factors it can act as a promoter in the malignant transformation from PMD to oral cancer. The studies conducted at Taiwan showed the similar kind of results.[24]

CONCLUSIONS

The relationship between chewing tobacco, smoking and alcohol drinking act as risk factors in the development of PMD and oral cancer. Various parameters such as age, gender, education, occupation and SES influenced the development of PMD and oral cancer.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zain RB, Ikeda N, Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S, van Wyk CW, Shrestha P, et al. Oral mucosal lesions associated with betel quid, areca nut and tobacco chewing habits: Consensus from a workshop held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 25-27, 1996. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saraswathi TR, Ranganathan K, Shanmugam S, Sowmya R, Narasimhan PD, Gunaseelan R, et al. Prevalence of oral lesions in relation to habits: Cross-sectional study in South India. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:121–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle P, Macfarlane GJ, Maisonneuve P, Zheng T, Scully C, Tedesco B, et al. Epidemiology of mouth cancer in 1989: A review. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:724–30. doi: 10.1177/014107689008301116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnakulasuriya S. Causes of oral cancer – An appraisal of controversies. Br Dent J. 2009;207:471–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy KS, Gupta PC. A Report on Tobacco Control in India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and World Health Organization, Prepared by Word Editorial Consultants, New Delhi. 2004:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auluck A, Hislop G, Poh C, Zhang L, Rosin MP. Areca nut and betel quid chewing among South Asian immigrants to Western countries and its implications for oral cancer screening. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Cabay RJ, Day T, Gonsalves W. Screening for and diagnosis of oral premalignant lesions and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Role of primary care physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:870–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichart PA, Nguyen XH. Betel quid chewing, oral cancer and other oral mucosal diseases in Vietnam: A review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:511–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen PE. Strengthening the prevention of oral cancer: The WHO perspective. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:397–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashibe M, Jacob BJ, Thomas G, Ramadas K, Mathew B, Sankaranarayanan R, et al. Socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors and oral premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:664–71. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campisi G, Margiotta V. Oral mucosal lesions and risk habits among men in an Italian study population. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:22–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kothari CR. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. 2nd ed. New Delhi: New Age International Publisher; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zini A, Czerninski R, Sgan-Cohen HD. Oral cancer over four decades: Epidemiology, trends, histology, and survival by anatomical sites. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang YH, Lee HY, Tung S, Shieh TY. Epidemiological survey of oral submucous fibrosis and leukoplakia in aborigines of Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:213–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanian S, Sankaranarayanan R, Bapat B, Somanathan T, Thomas G, Mathew B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of oral cancer screening: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in India. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:200–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandekar SP, Bagdey PS, Tiwari RR. Oral cancer and some epidemiological factors: A hospital based study. Indian J Commu Med. 2006;31:157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sankaranarayanan R, Duffy SW, Padmakumary G, Day NE, Krishan Nair M. Risk factors for cancer of the buccal and labial mucosa in Kerala, Southern India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990;44:286–92. doi: 10.1136/jech.44.4.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ariyawardana A, Sitheeque MA, Ranasinghe AW, Perera I, Tilakaratne WM, Amaratunga EA, et al. Prevalence of oral cancer and pre-cancer and associated risk factors among tea estate workers in the central Sri Lanka. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:581–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheifele C, Nassar A, Reichart PA. Prevalence of oral cancer and potentially malignant lesions among shammah users in Yemen. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ariyawardana A, Athukorala AD, Arulanandam A. Effect of betel chewing, tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption on oral submucous fibrosis: A case-control study in Sri Lanka. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen KT, Chen CJ, Fagot-Campagna A, Narayan KM. Tobacco, betel quid, alcohol, and illicit drug use among 13- to 35-year-olds in I-lan, Rural Taiwan: Prevalence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1130–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho PS, Yang YH, Shieh TY, Huang IY, Chen YK, Lin KN, et al. Consumption of areca quid, cigarettes, and alcohol related to the comorbidity of oral submucous fibrosis and oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:647–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashibe M, Mathew B, Kuruvilla B, Thomas G, Sankaranarayanan R, Parkin DM, et al. Chewing tobacco, alcohol, and the risk of erythroplakia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:639–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung CH, Yang YH, Wang TY, Shieh TY, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral precancerous disorders associated with areca quid chewing, smoking, and alcohol drinking in Southern Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:460–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]