Conspectus

The formation and subsequent on-demand dissolution of chemically cross-linked hydrogels is of keen interest to chemists, engineers, and clinicians. In this Account, we summarize our recent advances in the area of dissolvable chemically cross-linked hydrogels and provide a comparative discussion of other recent hydrogel systems. Using biocompatible macromonomers, we developed a library of cross-linked dendritic hydrogels that possess favorable properties, including biocompatibility, tissue adhesion, and swelling. Additionally, these hydrogels possess the unique ability to dissolve on-demand via application of a biocompatible aqueous solution. Each of the three hydrogel systems described employs a thiol–thioester exchange reaction as the mechanism of dissolution. These new materials successfully decrease bleeding in in vivo models of hepatic and aortic hemorrhage and dissolve on-demand, providing easy removal. In addition, we evaluated these hydrogels as dressings for second-degree burn wounds and performed proof-of-concept in vivo studies. These hydrogel wound dressings provide a means of repeatedly changing the dressing in a minimally invasive and atraumatic manner while also serving as a protective barrier against bacterial infection. Finally, we highlight the seminal work of other researchers in the field of dissolvable chemically cross-linked hydrogels using thiol–disulfide exchange, retro-Michael-type, and retro-Diels–Alder reactions. These chemistries provide a versatile synthetic toolbox to dissolve hydrogels in a controlled manner on time scales from minutes to weeks. Continued investigation of these dissolution approaches as well as the development of new chemical reactions will open doors to other avenues of on-demand dissolution and expand the application space for these materials. In summary, the management and closure of wounds after traumatic injury or surgical intervention are of significant clinical importance. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels that function as sealants, adhesives, or dressings are emerging as vital alternatives to current standards of care that rely upon conventional sutures, staples, or dressings.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Hydrogels are three-dimensional, hydrophilic, cross-linked networks that embed large amounts of water1 Hydrogels can be divided into two groups: physically and chemically cross-linked hydrogels2 Physically cross-linked hydrogels are based on networks formed by molecular entanglements and/or secondary forces, including ionic, H-bonding, or hydrophobic. Such hydrogels exhibit reversibility, as the network can be formed and dissolved with a stimulus such as a change in pH, ionic strength of the solution, or temperature. In contrast, chemically cross-linked hydrogels are formed via covalent bonds between macromolecular chains. Both natural (e.g., chitosan, hyaluronic acid, collagen, fibrin) and synthetic (e.g., poly(acrylic acid), poly(ethylene glycol), poly(vinyl alcohol), polyphosphazene, polypeptides) polymers are used to prepare hydrogels.

Hydrogels are of interest in the fields of chemistry and biomedical engineering, especially for applications in tissue engineering, wound healing, and drug delivery because of their biocompatibility, tunable biodegradability, and controllable mechanical properties.3 Optimal hydrogel materials should (1) be synthesized efficiently under relatively mild conditions, (2) possess structural and mechanical properties appropriate for an intended application, (3) be delivered in a minimally invasive manner, (4) be biocompatible, and (5) if necessary, be easily removable without the need for debridement via surgical or mechanical means. Synthetic hydrogels are particularly appealing for biomedical applications, as their chemistries and properties are controllable and reproducible, i.e., they are synthesized with macromonomers of specific molecular weights and architectures and possess degradable or nondegradable linkages and cross-linking modes. These controllable features enable optimization of the hydrogel formation kinetics, cross-linking density, dissolution rates, and mechanical properties.

Although there have been significant accomplishments in the development, characterization, and applications of chemically cross-linked hydrogels (with several hydrogel formulations commercialized),4 relatively minimal effort has been directed to the controlled and/or on-demand dissolution of chemically cross-linked hydrogels.5 Therefore, there are significant basic science and clinical opportunities to develop dissolvable chemically cross-linked hydrogels. Controlled material dissolution is particularly important for (1) atraumatic removal after it has served its function, (2) site-specific delivery of encapsulated therapeutics (e.g., proteins, small molecules, and cells), and (3) tailored administration of an agent with high efficiency. Dissolution of covalently cross-linked hydrogels is accomplished by incorporation of cleavable moieties that undergo ester hydrolysis or enzymatic degradation.6–8 Recently, thiol–thioester exchange, thiol–disulfide exchange, retro-Michael-type addition, and retro-Diels–Alder reactions have been described for hydrogel dissolution, and these chemistries will be discussed in detail in the following sections. These chemical transformations provide a responsive synthetic handle for engineering of hydrogel dissolution rates.

2. Thiol–Thioester Exchange

Thiol–thioester exchange occurs in water over a pH range relevant to biological processes, and hence, it is used in self-assembly transformations where physiological conditions are needed. However, despite being commonly encountered in biology, thiol–thioester exchange is less well understood in organic synthesis.9 The reaction relies on the reaction of a thiolate anion with a thioester to form new thiolate and thioester products (Scheme 1). In a competing process in water, thioesters hydrolyze to give carboxylic acids. The rates of exchange and hydrolysis depend on the temperature, pH of the solvent, and acidity of the thiol. The rate-determining step in the thiol–thioester exchange mechanism is determined by the relative pKa of the incoming and departing thiols.10 When the pKa of the conjugate acid of the nucleophilic thiolate is greater than that of the leaving thiolate, the rate-determining step is the formation of the tetrahedral intermediate. However, when the pKa of the attacking thiolate conjugate acid is lower than that of the leaving thiolate, the rate-determining step is the collapse of the tetrahedral intermediate. Interestingly, although alkyl thioester hydrolysis is thermodynamically favorable, reactions of thioesters with nucleophilic oxygen are relatively slow compared with reactions with nucleophilic sulfur, favoring the formation of the thiol–thioester exchange products and not hydrolysis.10

Scheme 1.

Thiol–Thioester Exchange Reaction

While hydrogels based on thiol–disulfide exchange or native chemical ligation (NCL) are known, in 2013 we disclosed the first example of hydrogel disassembly based on thiol–thioester exchange.11–14 We selected a dendritic macromonomer since its composition, structure, and molecular weight are precisely controlled to afford a species with multiple reactive sites for controllable hydrogel formation.15 Given that hydrogel dissolution is based on a thiol–thioester exchange reaction mechanism, we prepared dissolvable thioester-linked and nondissolvable amide-linked (control) hydrogels. Two lysine-based peptide dendrons 1 and 2, possessing four terminal thiols or amines, were synthesized in good yields, i.e., 46% over seven steps and 64% over five steps, respectively (Scheme 2). Following a previously reported procedure, the carboxybenzyl-protected (Cbz) lysine 4 was synthesized.16 To increase the aqueous solubility of the macromonomer, a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-amine (MW = 2 kDa) was introduced via a standard peptide coupling reaction, and subsequent hydro-genolysis of the Cbz groups gave dendron 2. Next, dendron 1 was synthesized by coupling pentafluorophenol (PFP)-activated 3-(tritylthio)propionic acid to dendron 2 and removing the trityl groups (Tr) with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and triethylsilane (Et3SiH) in dichloromethane (DCM). The identities of 1 and 2 were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR, FT-IR, and MALDI analyses.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic Route to Dendrons 1 and 2

To prepare the dissolvable hydrogel, a solution of 1 in borate buffer at pH 9.0 (0.1 M) was reacted with a solution of poly(ethylene glycol disuccinimidyl valerate) (3, SVA-PEG-SVA) (MW = 3.4 kDa) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM) at pH 6.5 (Scheme 3). The speed of hydrogel formation was controlled by the pH and capacity of both buffer solutions and chosen appropriately for a given application. The total polymer concentration in solution was either 10 or 30 wt %, and the ratio of thiol (dendron) to SVA (cross-linker) was 1:1. As a control, a nondissolvable hydrogel was prepared, following the same procedure, by mixing 2 with 3. Both hydrogels formed spontaneously within minutes upon mixing an appropriate aqueous dendron solution with 3 at either concentration. The transparent hydrogels exhibited viscoelastic properties with storage modulus (G′) values in the range of 6–37 kPa, which were dependent on the weight percent of polymer (Figure 1). Depending on the weight percent, the hydrogels swelled up to 200–600%.

Scheme 3.

Hydrogel Formation via Mixing of 1 and 3

Figure 1.

Rheological properties of hydrogels.

To determine whether a thiol–thioester exchange reaction between the thioester bonds in the network and an exogenous thiolate solution is responsible for hydrogel dissolution, we used both dissolvable (thioester-linked) and nondissolvable (amide-linked) formulations at 30 wt % after equilibrium swelling in PBS (pH 7.4) (Figure 2). We examined dissolution under three conditions: (1) a solution of l-cysteine methyl ester (CME) as the nucleophile based on the NCL mechanism, (2) a water-soluble 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate solution (MESNA), and (3) an aqueous l-lysine methyl ester (LME) solution. The concentration of the solution as well as the pH of the buffer affected the rate of exchange and thus the dissolution time. When we increased the concentration of the CME solution from 0.3 to 0.5 M at a constant pH of 7.4, we observed a decrease in the dissolution time from ∼1 h to ∼36 min. Analogously, when the pH was increased from 7.4 to 8.5 and while the concentration of CME solution was kept constant at 0.3 M, the network was cleaved in ∼24 min compared with 50 min. Upon exposure to MESNA solution (0.3 M, pH 8.5) in PBS, the dissolution profile of the thioester-containing hydrogel was similar to that with CME, i.e. ∼20 min. Exposure to 0.3 M LME solution (pH 8.5) in PBS did not cleave the thioester linkages in the dissolvable hydrogel even after 1 h. Exposing the nondissolvable hydrogel to 0.3 M CME solution (pH 8.5) did not dissolve the hydrogel after prolonged exposure.

Figure 2.

Hydrogel dissolution as monitored by rheometry. Adapted with permission from ref 14. Copyright 2013 Wiley-VCH.

The adherence of the hydrogel to ex vivo human skin was then examined by applying both formulations to skin and exerting torsional stress to test their adherence strength and flexibility. Both hydrogels remained intact. Exposure of the hydrogels to a 0.3 M CME solution (pH 8.5) resulted in removal of the dissolvable hydrogel, while the nondissolvable formulation swelled and remained adhered even after several hours. The mechanisms of tissue adhesion may involve mechanical interlocking and/or chemical bonding.

Additionally, we investigated whether the dissolvable hydrogel could seal punctures in an ex vivo bovine jugular vein and then be dissolved. A vein was secured to a testing apparatus and subjected to an internal water pressure of 250 mmHg. Upon puncturing a 2.5 mm hole in the vein, water leaked and the pressure dropped to 0 mmHg. Once sealed with the hydrogel (30 wt %), the material secured the puncture site within 5 min without leakage as the pressure continuously increased to approximately 250 mmHg. Application of CME resulted in hydrogel dissolution, a leak, and return of the pressure to 0 mmHg.

To initially assess the safety profile of the dissolvable hydrogel (30 wt %), in vitro cytotoxicity with NIH3T3 murine fibroblast cells and in vitro macrophage activation studies to measure production of IL-6 were performed. After exposure to the hydrogel for 24 h, the cell viability was 97 ± 3%, which was similar to that of the untreated control, and the hydrogel did not elicit an elevated IL-6 response. In vivo studies are required in order to determine the safety.

The successful development of a dissolvable hydrogel led us to investigate a different hydrogel formulation as a sealant for the treatment of severe hepatic and aortic hemorrhage.17 Hemorrhage is the leading cause of preventable death after traumatic injury.18 Compressible hemorrhage can normally be stopped using constant and direct manual pressure with a tourniquet.19 However, junctional zones, such as the neck and groin, present a particular problem for hemorrhage control because of the difficulty in maintaining effective compression. In these noncompressible areas, materials such as hydrogels can be used as sealants or hemostatic agents. However, a problem associated with the use of these materials is the difficulty with their removal, as typically they are surgically debrided. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop a new sealant for hemorrhage control. We envisioned such sealant to be easily applied and form in situ in 1–2 s, accommodate complex wound contours, be flexible and biocompatible, control severe arterial and venous bleeding without the need for compression, and most importantly, be removed atraumatically under controlled conditions for definitive surgical care.

When performing the above characterization studies, we realized that gelation was too slow for hemorrhage control, as the hydrogel precursors would be diluted with blood prior to forming a hydrogel. A hydrogel that forms within 1 s is required. Hence, we prepared a new cross-linker containing internal thioesters and maleimide (MAL) end-capped moieties for instantaneous gelation. At pH 6.5–7.5, thiols react specifically with maleimides to form a stable thioether covalent bond.

Analogously to the previous formulations, the hydrogel is composed of two components: thiol-capped dendron 1 and MAL-capped cross-linker 5. The latter was prepared by reacting 3 with thioglycolic acid and N,N′-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) to yield thioester bonds (Scheme 4). Then the polymer was capped with MAL groups via coupling with (benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluoro-phosphate (PyBOP). A hydrogel sealant was formed within 1 s upon mixing of 1 dissolved in borate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.0) with 5 in PBS (10 mM, pH 6.5). The total concentration of the polymer in solution was 30 wt %, and the ratio of thiol to MAL was 1:1. Importantly, the hydrogel sealant formed instantaneously in situ. As determined by rheological measurements, the optically transparent hydrogel exhibited viscoelastic behavior with G′ = 9 kPa.

Scheme 4.

Hemorrhage Cross-Linker Synthesis

Next, we investigated the on-demand dissolution of the hydrogel using an ex vivo pressure testing system.20 The testing device consisted of a flow and pressure sensor assembly connected to a cylindrical reservoir that was lined with ex vivo rat skin. A 2.5 mm incision was made on the otherwise intact tissues and sealed with the hydrogel. Then the pressure within the system was increased to a maximum of 120 mmHg (Figure 3). If no dissolution agent was administered or if LME (0.3 M, pH 8.5) was applied, no drop in the pressure of the system was noted. However, when CME (0.3 M, pH 8.5) was applied to the hydrogel, after about 10 min a drop in pressure signified dissolution. On the other hand, no dissolution occurred when the hydrogel with no thioester bonds in the network (1 and 3) was exposed to CME.21 Similar to the previous hydrogel, no in vitro cytotoxicity or elevated IL-6 response was observed with this dissolvable hydrogel formulation.

Figure 3.

Hemorrhage sealant dissolution. Reproduced with permission from ref 17. Copyright 2017 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

To determine the in vivo efficacy of the hydrogel sealant, we measured blood loss reduction in both severe hepatic and aortic hemorrhage rat models. We first tested our sealant in a venous hemorrhage model (blood pressure 8–12 mmHg).22 Prior to experimentation, all of the rats were anticoagulated with heparin. A severe hepatic injury was induced by excising ∼20% of the median lobe of the rat's liver. After 20 s of active bleeding, in the treatment group, the hydrogel was applied directly on the actively bleeding wound. In the control group, no treatment was administered. After 20 min had elapsed, blood in the abdominal cavity was collected, and the postinjury blood loss was quantified. The hydrogel reduced postinjury blood loss by 33% (statistically significant reduction) in severe hepatic hemorrhage compared with the untreated controls. In the aortic hemorrhage model (blood pressure 100 mmHg), after anticoagulation a severe arterial injury was induced by inserting a 25-gauge needle into the abdominal aorta.23 In the treatment group, the hydrogel was immediately applied on the actively bleeding aorta, whereas in the control group, no treatment was administered. After 20 min had elapsed, blood in the abdominal cavity was collected, and the postinjury blood loss was quantified. The hydrogel reduced the postinjury blood loss by 22% (statistically significant reduction) in the aortic hemorrhage compared with the untreated controls.

Next, we turned our attention to designing an on-demand dissolvable hydrogel dressing for the treatment of second-degree burns.24 The design requirements for a second-degree burn dressing include elasticity to accommodate movement, ability to absorb wound exudate, lessening of trauma to the wound during dressing changes, biocompatibility, and protection of the wound from infections. Moreover, from discussions with Dr. Robert L. Sheridan (Medical Director, Burn Service at Boston Shriners Hospitals for Children), we learned that procedural pain is severe during burn dressing change. A dressing that dissolves on-demand and allows for a facile change may provide a pain-free procedure. As the design requirements for the hydrogel changed from the preceding application, we identified a formulation that exhibited enhanced stability, slower hydrogel formation, and faster dissolution. The original thiol-capped dendron oxidized in air to disulfides and had to be handled with caution, limiting its shelf life. If oxidized, the thiol groups cannot participate in cross-linking. To address this challenge, we designed a hydrogel in which thioester bonds were present in the PEG cross-linker as opposed to being formed during the gelation process. Therefore, we used 2 with nucleophilic amines to cross-link with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-capped PEG 6 with two internal thioester linkages. Similarly to the previous formulations, the gelation time was dependent on the buffer pH.

Cross-linker 6 was synthesized by reacting 3 with thioglycolic acid in the presence of DIPEA to introduce two thioester groups (Scheme 5). Subsequently, the species was capped with NHS groups using N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC). The hydrogel dressing was prepared by mixing a solution of 2 in borate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.6) with a solution of 6 in PBS (10 mM, pH 6.5). The total polymer concentration in solution was 40 wt %, and the ratio of amine to NHS was 1:1. In this hydrogel system, the amines on 2 reacted with the NHS esters of 6, giving amide bonds in the network. The hydrogel's in situ gelation allowed the dressing to be easily applied as a solution to areas difficult to access with conventional preshaped dressings. Additionally, the hydrogel dressing was stable toward hydrolysis for several days in PBS (pH 7.4). The transparent hydrogel exhibited viscoelastic properties with G′ = 13 kPa and swelled to 650% in 18 h, reaching equilibrium.

Scheme 5.

Burn Cross-Linker Synthesis

We also measured the adhesive properties of the hydrogel to murine skin using an established lap-shear test (ASTM F2255-05). Upon increasing the shear stress, rupture of the hydrogel occurred within the bulk of the material rather than at the tissue–hydrogel interface. Control experiments conducted with only the dendron or cross-linker solutions did not yield a seal and the tissue sections remained separated, indicating that the cross-linker/dendron did not chemically bind the tissue to make a seal.

To investigate its dissolution, we performed rheological measurements via a time sweep (Figure 4). When the thioester-containing hydrogel was exposed to CME (0.3 M, pH 8.6) for 30 min, its dissolution was observed (G′ < 200 Pa). When it was subjected to LME (0.3 M, pH 8.5) or air, no change in the mechanical properties was noted. A control hydrogel prepared using 2 and 3 (without thioester bonds) did not dissolve after 1 h when exposed to CME (0.3 M, pH 8.6), confirming that the hydrogel dissolution mechanism proceeded via thiol–thioester exchange. We also observed the on-demand dissolution of the hydrogel when it was applied to a second-degree burn wound on a rat. As time elapsed and CME-soaked gauzes were administered to the hydrogel, complete dissolution occurred within 30 min. Accordingly, in the clinic, the CME solution would be administered onto the hydrogel with irrigation. Similar to the above hydrogels, no in vitro cytotoxicity or elevated IL-6 response was observed with this dissolvable hydrogel formulation.

Figure 4.

Burn dressing dissolution. Reproduced with permission from ref 24. Copyright 2016 Wiley-VCH.

Finally, we evaluated the hydrogel efficacy in preventing wound infection and sepsis in an animal model of second-degree burn.25 We induced second-degree burns covering approximately 5% of total body surface area on rats. Then the animals were divided into three groups: (1) burn only (negative controls), (2) burn + bacterial contamination (positive controls), and (3) burn + hydrogel + bacterial contamination (hydrogel-treated group). Bacterial contamination was achieved by covering the burn and the burn + hydrogel wounds with a gauze containing 2 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of log-phase Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Upon euthanization at 72 h, the concentrations of bacteria were measured in the spleen (systemic infection) and in the burn wound (local infection), and the differences in the concentrations were compared among the groups.26 In the hydrogel-treated groups, the local and systemic bacterial proliferation was statistically significantly lower than that of the positive controls. Also, there was no statistically significant difference between the negative controls and the treatment groups.

3. Thiol–Disulfide Exchange

The thiol–disulfide exchange reaction is key to a number of important biological processes, such as the formation and cleavage of structural cysteine disulfide bonds and disulfide-mediated redox reactions. Mechanistically, thiol–disulfide exchange consists of initial ionization of the thiol to thiolate anion in a basic medium, nucleophilic attack (SN2 displacement) of the thiolate anion on a sulfur atom of the disulfide moiety, and protonation of the product thiolate anion.27 These three steps are reversible. From a materials perspective, the reversible thiol–disulfide exchange is triggered to initiate controllable changes in the material properties (e.g., hydrogel modulus).28 The reversible cross-links are typically incorporated into the polymer chains via reductively cleavable disulfide groups. The thiol–disulfide exchange reaction is driven using an excess of thiolate and its pKa.

Recent examples of thiol–disulfide exchange reactions to form and subsequently dissolve hydrogels were described by Sinko.11 The hydrogels were formed in situ by covalent cross-linking of polymer chains through reversible disulfide bonds. The hydrogels were based on 8-arm-PEG-SH (MW = 20 kDa) cross-linked in the presence of either H2O2 (H2O2 hydrogel; 2, 8 wt %) or 8-arm-PEG-S-TP (S-TP hydrogel; 5, 8 wt %; S-TP = sulfur-thiopyridine) in PBS (pH 8.0). The H2O2-initiated hydrogels formed within 1 min, while the S-TP hydrogels gelled within 10 s. The H2O2 hydrogels exhibited a swelling degree of <1.0, whereas the S-TP hydrogels swelled to <1.5. Rheological measurements indicated elastic behavior of the materials.

As the thiol–disulfide reaction was being used to dissolve the hydrogel, glutathione (GSH) (1, 3, 5% w/v in PBS, pH 7.4) was identified as the dissolution agent. GSH acted as a thiolate moiety, cleaving the existing disulfide bonds and simultaneously becoming oxidized. In its presence, the hydrogel dissolved within 30–40, 15–20, and 10–15 min when the 1, 3, and 5% (w/v) GSH solutions, respectively, were used. The dissolution products were 8-arm-PEG-SH, 8-arm-PEG-S-SG, GS-SG, and 8-arm-PEG-SH bearing either SH or S-SG termini (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hydrogel dissolution products.

The hydrogels were loaded with doxycycline (0.25% w/v) and evaluated in the treatment of mustard-gas-injured skin in an in vivo mouse model. Elevated doxycycline permeability (8.5 mg/cm3) through injured skin was observed compared with unreacted or placebo controls at 24, 72, and 168 h postinjury, with the highest permeability at 72 h. After 168 h, the doxycycline permeability decreased and epidermal re-epithelialization was observed.

4. Retro-Michael Reaction

Another class of dissolvable hydrogels is based on materials prepared via conjugate addition reaction, i.e., Michael-type addition reaction (Scheme 6A).29 One common strategy to synthesize hydrogels employs MAL-functionalized macromonomers cross-linked with various thiol-functionalized PEG multiarm star polymers, yielding a network cross-linked with thioether linkages. The thiol–MAL Michael addition reaction is selective in aqueous environments (at physiological pH, amines react generally at least 1 order of magnitude slower than thiols)30 as a result of the rapid reaction kinetics and the relative stability of the thiol–MAL product. The dissolution reaction mechanism involves covalent bond transfer from the initial succinimide thioether compound to a stable GSH conjugate in the presence of excess reductant (Scheme 6B). The rate and extent of this reaction are governed by the retro-addition rate, and this can be modulated by controlling the reactivity of the Michael donor.31 For example, aromatic thiols (pKa ∼ 7) are better Michael donors than aliphatic thiols (pKa ∼ 11) and thus are better leaving groups, allowing for faster dissolution in a reductive environment. On the other hand, the use of a Michael donor with sufficiently high pKa hinders the retro reaction.

Scheme 6.

(A) Michael Addition; (B) Retro-Michael Reaction

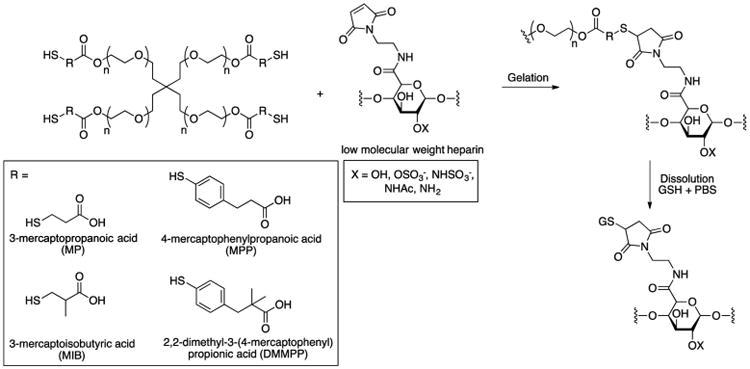

Recently, Kiick showed that succinimide–thioether linkages formed via Michael-type addition of thiols to maleimides were cleaved by exogenous GSH.32,33 In their report, hydrogels (5 wt %) were formed in situ by mixing solutions of thiolated 4-arm-PEG (MW = 10 kDa) and MAL-functionalized low-molecular-weight heparin (MAL-LMWH) (Scheme 7). Hydrogels prepared with alkyl thiol-functionalized PEGs (3-mercaptopro-panoic acid, MP; 3-mercaptoisobutyric acid, MIB) gelled at pH 7.0 and 25 °C, while hydrogels prepared with aryl thiol-functionalized PEGs (4-mercaptophenylpropanoic acid, MPP; 2,2-dimethyl-3-(4-mercaptophenyl)propionic acid, DMMPP) gelled at pH 6.6 and 4 °C.

Scheme 7.

Hydrogel Formation and Dissolution

Rheological studies revealed that gelation occurred in <6, 15, 50, and 90 s for the PEG-MPP, -DMMPP, -MP, and -MIB hydrogels, respectively. The authors attributed the rate of hydrogel gelation to the Michael donor reactivity of the thiol, as the phenylthiol derivatives possess lower pKa values than the alkyl thiols (6.6 vs 10.3) and exhibit higher reaction rates. The G′ values for all of the hydrogels were approximately 2.1 kPa.

NMR characterization validated the GSH sensitivity of the PEG-MPP and PEG-DMMPP hydrogels resulting from retro-Michael addition-mediated cleavage of the succinimide–thioether bond. The samples were formed and then swelled in deuterated PBS containing 10 mM GSH, and the liberated dissolution products containing thiols were detected. By day 4, most of the succinimide–thioether linkages had degraded, yielding mainly PEG-MPP. Hydrogels incubated in the absence of GSH did not show the disappearance of the peaks from soluble MEG-MPP.

Rheometry was used to measure the kinetics of dissolution and the changes in mechanical properties due to dissolution in the presence of GSH-containing buffer. Under highly reducing conditions (10 mM GSH), PEG-DMMPP dissolved in ∼90 h, while PEG-MMP dissolved in ∼72 h. Interestingly, the PEG-MMP- and PEG-DMMPP-containing hydrogels exhibited a lower susceptibility to GSH than disulfide-containing hydrogels (consistent with the observation that the rate constants for the retro-Michael-type addition are 1 order of magnitude lower than those for glutathione–disulfide exchange).34

In addition, heparin release was assessed as a function of hydrogel dissolution. The hydrogels containing the GSH-sensitive succinimide–thioether linkages, i.e., PEG-MPP and PEG-DMMPP, released 100% LMWH in 12 and 20 days, respectively, under standard reducing conditions (10 μM GSH). Under highly reducing conditions (10 mM GSH), PEG-MPP and PEG-DMMPP dissolved rapidly, with 100% LMWH release in 3 and 4 days, respectively. The release profiles of the PEG-MP and PEG-MIB hydrogels showed significantly less sensitivity to reducing conditions, requiring 20 (PEG-MP) and 49 days (PEG-MIB) under standard conditions and 17 (PEG-MP) and 33 days (PEG-MIB) under highly reducing conditions (in their previous studies, retro-Michael-type reactions were not observed for PEG-MP- and PEG-MIB-containing substrates).39

5. Retro-Diels–Alder Reaction

Another class of dissolvable hydrogels relies on the Diels–Alder (DA) reaction and its counterpart, the retro-Diels–Alder (rDA) fragmentation, which are reversible at elevated temperatures.35 Typically, in the DA cycloaddition, hydrogels are formed via a highly specific cyclization reaction between a conjugated diene and a substituted alkene dienophile in water.36,37 Early examples of this reversible reaction chemistry with hydrogels required temperatures above 60 °C for dissolution or introduced hydrolytically or enzymatically cleavable sites to render the hydrogels biodegradable or dissolvable. The majority of systems reported do not readily undergo dissolution at 37 °C because of a low rate of rDA reaction and high cross-linking density of the polymers, thus limiting their translation into biological milieus.38 Hydrogel dissolution requires multiple rDA reactions to occur simultaneously at a significant rate, which is challenging to achieve in highly cross-linked networks. To address these limitations, investigators are exploring novel DA hydrogel systems with greater reactivity for rDA.

An example of rDA fragmentation to dissolve a hydrogel was reported by Goepferich and co-workers.39 They prepared DA hydrogels by mixing equimolar amounts of furyl and MAL-substituted PEGs of the same molecular weight and branching factor in water (i.e., 4-arm-PEG10k hydrogel, 4-arm-PEG20k hydrogel, 8-arm-PEG10k hydrogel, and 8-arm-PEG20k hydrogel). Rheological characterization of the DA hydrogels revealed the gelation time and mechanical properties to be dependent on the polymer concentration, the branching factor, and the molecular weight of the macromonomers.

To confirm that the hydrogel dissolution proceeded via rDA reaction, a 5 wt % 4-arm-PEG10k hydrogel was prepared in D2O, swollen in deuterated PBS (pH 7.4) until dissolution, and then analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Immediately after mixing of the precursors, a 1H NMR spectrum showed peaks corresponding to 4-arm-PEG10k-maleimide and 4-arm-PEG10k-furan. After 72 h of cross-linking, peaks corresponding to the cycloaddition product were noted. However, after dissolution, signals corresponding to the 4-arm-PEG10k-furan were observed. In addition, no signals for 4-arm-PEG10k-maleimide were detected, and instead, alkenyl peaks corresponding to the hydrolyzed (ring-opened) form of 4-arm-PEG10k-maleimide were present. Moreover, because of the higher macromonomer concentration in the 8-arm-PEG10k hydrogel than in the 4-arm-PEG10k hydrogel, the dissolution of the 8-arm-PEG10k hydrogel proceeded slower. At 37 °C, the dynamic equilibrium of the DA reaction lies toward the side of the cycloaddition products, but small amounts of unreacted MAL and furyl groups were still present. The MAL groups were free to react with furyl groups to form a DA adduct or undergo hydrolysis to maleamic acid derivatives if they did not form cycloaddition products (Scheme 8). As a result of hydrolysis to the unreactive maleamic acid derivatives, the existing MAL groups were continuously removed from the dynamic equilibrium, and the DA reaction was ultimately reversed. Therefore, the authors hypothesized that the average network mesh size and hydrogel swelling capacity increased gradually until a critical number of elastically active chains was broken and the hydrogel dissolved. Once a macromonomer was released from the network of a dissolving hydrogel, more starting material was removed from the equilibrium by diffusion into the surrounding buffer, accelerating the rDA reaction independent from the hydrolysis of the MAL groups. Their initial studies were later supplemented by a detailed mechanistic investigation of dissolution using rheometry.40

Scheme 8.

Potential rDA Dissolution Pathway

6. Conclusion

We are particularly excited about on-demand dissolvable hydrogels, as this research area provides an opportunity for groundbreaking basic research with findings applicable to clinical challenges. The four different hydrogel dissolution chemistries described (i.e., thiol–thioester exchange reaction, thiol–disulfide exchange reaction, retro-Michael-type reaction, and retro-Diels–Alder reaction) provide a versatile synthetic toolbox to dissolve hydrogels in a controlled manner (Table 1). Continued research and development are imperative, as some of the current dissolvable hydrogels have minimal data on toxicity or exhibit slow dissolution. New cross-linking and dissolution chemistries (both covalent and non-covalent) along with modes of dissolution from the application site (aqueous wash, mechanical force, etc.) are needed. We ask the community to participate in finding new solutions. Finally, communication with medical professionals (MDs, RNs, DMDs, DVMs, MPHs) is key, as identifying and understanding the device performance requirements is necessary for translation.

Table 1. Summary of On-Demand Dissolvable Chemically Cross-Linked Hydrogels.

| dissolution mode | dissolution time | dissolution trigger | research group | ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thiol–thioester exchange | 10–30 min | CME | Grinstaff | 14, 17, 24 |

| thiol–disulfide exchange | within 1 h | GSH | Sinko | 11 |

| retro-Michael reaction | 72–90 h | GSH | Kiick | 32, 33 |

| retro-Diels–Alder reaction | days to weeks | hydrolysis of unreactive maleamic acid derivatives | Goepferich | 39 |

Acknowledgments

Our work was supported by the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, BU, and the NIH (R01EB021308).

Biographies

Marlena D. Konieczynska obtained her B.A. from Rutgers University and her Ph.D. in chemistry from Boston University in the lab of Professor Mark W. Grinstaff, where she worked on the synthesis and in vivo applications of hydrogels. Currenty she is the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellow and holds a joint postdoctoral appointment at BU and Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center, Harvard Medical School.

Mark W. Grinstaff is the Distinguished Professor of Translational Research and a Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Chemistry, Materials Science and Engineering, and Medicine at Boston University. He is also the Director of the Nanotechnology Innovation Center (BUnano), the Director of the NIH T32 Biomaterials Program, and the Associate Director for Engineering and Science at the Cancer Center. He has published more than 250 peer-reviewed articles, and his innovative ideas and efforts have led to one new FDA-approved pharmaceutical and four medical device products that have improved patient care.

Footnotes

ORCID: Mark W. Grinstaff: 0000-0002-5453-3668

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Wichterle O, Lim D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature. 1960;185(4706):117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering: Scaffold Design Variables and Applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peppas NA, Bures P, Leobandung W, Ichikawa H. Hydrogels in Pharmaceutical Formulations. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):27–46. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caló E, Khutoryanskiy VV. Biomedical Applications of Hydrogels: A Review of Patents and Commercial Products. Eur Polym J. 2015;65:252–267. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kharkar PM, Kiick KL, Kloxin AM. Designing Degradable Hydrogels for Orthogonal Control of Cell Microenvironments. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(17):7335–7372. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60040h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrbar M, Rizzi SC, Schoenmakers RG, San Miguel B, Hubbell JA, Weber FE, Lutolf MP. Biomolecular Hydrogels Formed and Degraded via Site-Specific Enzymatic Reactions. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(10):3000–3007. doi: 10.1021/bm070228f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Tsutsui Y, Matsunaga T, Shibayama M, Chung U, Sakai T. Precise Control and Prediction of Hydrogel Degradation Behavior. Macromolecules. 2011;44(9):3567–3571. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicodemus GD, Bryant SJ. Cell Encapsulation in Biodegradable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng, Part B. 2008;14(2):149–165. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson R, Pei Z, Ramström O. Catalytic Self-Screening of Cholinesterase Substrates from a Dynamic Combinatorial Thioester Library. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43(28):3716–3718. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hupe DJ, Jencks WP. Nonlinear Structure-Reactivity Correlations. Acyl Transfer between Sulfur and Oxygen Nucleophiles. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99(2):451–464. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anumolu SS, Menjoge AR, Deshmukh M, Gerecke D, Stein S, Laskin J, Sinko PJ. Doxycycline Hydrogels with Reversible Disulfide Cross-links for Dermal Wound Healing of Mustard Injuries. Biomaterials. 2011;32(4):1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wathier M, Johnson CS, Kim T, Grinstaff MW. Hydrogels Formed by Multiple Peptide Ligation Reactions to Fasten Corneal Transplants. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17(4):873–876. doi: 10.1021/bc060060f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu BH, Su J, Messersmith PB. Hydrogels Cross-Linked by Native Chemical Ligation. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(8):2194–2200. doi: 10.1021/bm900366e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghobril C, Charoen K, Rodriguez EK, Nazarian A, Grinstaff MW. A Dendritic Thioester Hydrogel Based on Thiol-Thioester Exchange as a Dissolvable Sealant System for Wound Closure. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52(52):14070–14074. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlmark A, Hawker C, Hult A, Malkoch M. New Methodologies in the Construction of Dendritic Materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(2):352–362. doi: 10.1039/b711745k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wathier M, Johnson MS, Carnahan MA, Baer C, McCuen BW, Kim T, Grinstaff MW. In Situ Polymerized Hydrogels for Repairing Scleral Incisions Used in Pars Plana Vitrectomy Procedures. ChemMedChem. 2006;1(8):821–825. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konieczynska MD, Villa-Camacho JC, Ghobril C, Perez-Viloria M, Blessing WA, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK, Grinstaff MW. A Hydrogel Sealant for the Treatment of Severe Hepatic and Aortic Trauma with a Dissolution Feature for Post-Emergent Care. Mater Horiz. 2017 doi: 10.1039/C6MH00378H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of Hemorrhage on Trauma Outcome: An Overview of Epidemiology, Clinical Presentations, and Therapeutic Considerations. J Trauma: Inj, Infect, Crit Care. 2006;60(6):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kragh JFJ, Littrel ML, Jones JA, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Battle Casualty Survival with Emergency Tourniquet Use to Stop Limb Bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villa-Camacho JC, Ghobril C, Anez-Bustillos L, Grinstaff MW, Rodríguez EK, Nazarian A. The Efficacy of a Lysine-Based Dendritic Hydrogel Does Not Differ from Those of Commercially Available Tissue Sealants and Adhesives: An Ex Vivo Study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2015;16:116. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson ECB, Kent SBH. Insights into the Mechanism and Catalysis of the Native Chemical Ligation Reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(20):6640–6646. doi: 10.1021/ja058344i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holcomb JB, McClain JM, Pusateri AE, Beall D, Macaitis JM, Harris RA, MacPhee MJ, Hess JR. Fibrin Sealant Foam Sprayed Directly on Liver Injuries Decreases Blood Loss in Resuscitated Rats. J Trauma. 2000;49(2):246–250. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti L, Qiu X, Villalta J, Lin G. Efficacy of BloodSTOP iX, Surgicel, and Gelfoam in Rat Models of Active Bleeding from Partial Nephrectomy and Aortic Needle Injury. Urology. 2012;80(5):1161.e1–1161.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konieczynska MD, Villa-Camacho JC, Ghobril C, Perez-Viloria M, Tevis KM, Blessing WA, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK, Grinstaff MW. On-Demand Dissolution of a Dendritic Hydrogel-Based Dressing for Second-Degree Burn Wounds through Thiol–Thioester Exchange Reaction. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55(34):9984–9987. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borman H, Maral T, Demirhan B, Haberal M. Skin Flap Survival after Superficial and Deep Partial-Thickness Burn Injury. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;43(5):513–518. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnea Y, Carmeli Y, Kuzmenko B, Gur E, Hammer-Munz O, Navon-Venezia S. The Establishment of a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa-Infected Burn-Wound Sepsis Model and the Effect of Imipenem Treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(6):674–679. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000203984.62284.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houk J, Whitesides GM. Structure-Reactivity Relations for Thiol-Disulfide Interchange. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109(22):6825–6836. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gyarmati B, Némethy Á, Szilágyi A. Reversible Disulphide Formation in Polymer Networks: A Versatile Functional Group from Synthesis to Applications. Eur Polym J. 2013;49(6):1268–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair DP, Podgórski M, Chatani S, Gong T, Xi W, Fenoli CR, Bowman CN. The Thiol-Michael Addition Click Reaction: A Powerful and Widely Used Tool in Materials Chemistry. Chem Mater. 2014;26(1):724–744. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman M, Cavins JF, Wall JS. Relative Nucleophilic Reactivities of Amino Groups and Mercaptide Ions in Addition Reactions with A,β-Unsaturated Compounds 1,2. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87(16):3672–3682. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldwin AD, Kiick KL. Tunable Degradation of Maleimide–Thiol Adducts in Reducing Environments. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22(10):1946–1953. doi: 10.1021/bc200148v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baldwin AD, Kiick KL. Reversible Maleimide–thiol Adducts Yield Glutathione-Sensitive Poly(ethylene Glycol) –heparin Hydrogels. Polym Chem. 2013;4(1):133–143. doi: 10.1039/C2PY20576A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nie T, Akins RE, Jr, Kiick KL. Production of Heparin-Containing Hydrogels for Modulating Cell Responses. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(3):865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elbert DL, Pratt AB, Lutolf MP, Halstenberg S, Hubbell JA. Protein Delivery from Materials Formed by Self-Selective Conjugate Addition Reactions. J Controlled Release. 2001;76(1-2):11–25. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koehler KC, Anseth KS, Bowman CN. Diels–Alder Mediated Controlled Release from a Poly(ethylene Glycol) Based Hydrogel. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(2):538–547. doi: 10.1021/bm301789d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nimmo CM, Owen SC, Shoichet MS. Diels–Alder Click Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(3):824–830. doi: 10.1021/bm101446k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan H, Rubin JP, Marra KG. Direct Synthesis of Biodegradable Polysaccharide Derivative Hydrogels Through Aqueous Diels-Alder Chemistry. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2011;32(12):905–911. doi: 10.1002/marc.201100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanyal A. Diels–Alder Cycloaddition-Cycloreversion: A Powerful Combo in Materials Design. Macromol Chem Phys. 2010;211(13):1417–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirchhof S, Brandl FP, Hammer N, Goepferich AM. Investigation of the Diels-Alder Reaction as a Cross-Linking Mechanism for Degradable Poly(ethylene Glycol) Based Hydrogels. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1(37):4855–4864. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20831a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchhof S, Strasser A, Wittmann HJ, Messmann V, Hammer N, Goepferich AM, Brandl FP. New Insights into the Cross-Linking and Degradation Mechanism of Diels–Alder Hydrogels. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3(3):449–457. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01680g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]