Abstract

Generating appropriate defensive behaviors in the face of threat is essential to survival. Although many of these behaviors are ‘hard-wired’, they are also flexible. For example, Pavlovian fear conditioning generates learned defensive responses, such as conditioned freezing, that can be suppressed through extinction. The expression of extinguished responses is highly context-dependent, allowing animals to engage behavioral responses appropriate to the contexts in which threats are encountered. Likewise, animals and humans will avoid noxious outcomes if given the opportunity. In instrumental avoidance learning, for example, animals overcome conditioned defensive responses, including freezing, in order to actively avoid aversive stimuli. Recent work has greatly advanced understanding of the neural basis of these phenomena and has revealed common circuits involved in the regulation of fear. Specifically, the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex play pivotal roles in gating fear reactions and instrumental actions, mediated by the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, respectively. Because an inability to adaptively regulate fear and defensive behavior is a central component of many anxiety disorders, the brain circuits that promote flexible responses to threat are of great clinical significance.

Introduction

Natural selection has prepared us for a dangerous world. Whether a mouse, monkey, or human, an animal’s capacity to survive the myriad of threats in the environment depends on a finely-tuned repertoire of defensive behaviors. Of course, it is not only essential for animals to rapidly detect and respond to imminent threats, but it is also critical that they learn to anticipate when and where threats are likely to occur. In the last century, neuroscientists have focused on an important form of learning that both humans and animals use to anticipate threats: Pavlovian fear conditioning [1–3]. In this form of learning, animals associate innocuous conditional stimuli (CSs) with aversive unconditional outcomes (USs), much in the way one might associate the trauma of a robbery with the parking lot in which it occurs. After as little as a single trial, animals will come to fear the CS and exhibit a constellation of conditional responses (CRs) including freezing and hypertension.

Although defensive responses are relatively invariant and drawn from an innate repertoire [4], animals must also adapt to a changing environment—it is critical to be flexible in the face of fear. What was once a threat may no longer be so. For example, getting robbed in a parking lot does not necessarily mean that the lot will always be dangerous. A failure to adjust expectations accordingly can lead to costly disruptions of normal behavior. In a similar vein, if one is crossing the street and a car horn sounds, it might be one’s first instinct to freeze, even though the most adaptive thing is to cross to the other side. The dominant reaction to a threatening cue can be suppressed in favor of a more effective behavioral strategy. In the face of changing environmental contingencies, it is highly adaptive for humans and animals to adjust their defensive reactions to reflect an updated reality.

Here we review recent research that offers important insights into how the brain uses new information to guide adaptive responses to expected danger. In humans, failing to adaptively regulate fear is a core symptom of many anxiety-, stress- and trauma-related disorders. Thus, adaptive flexibility in the face of fear, as well as the brain substrates by which it is achieved, has a strong clinical significance.

Extinction and contextual control of defensive behavior

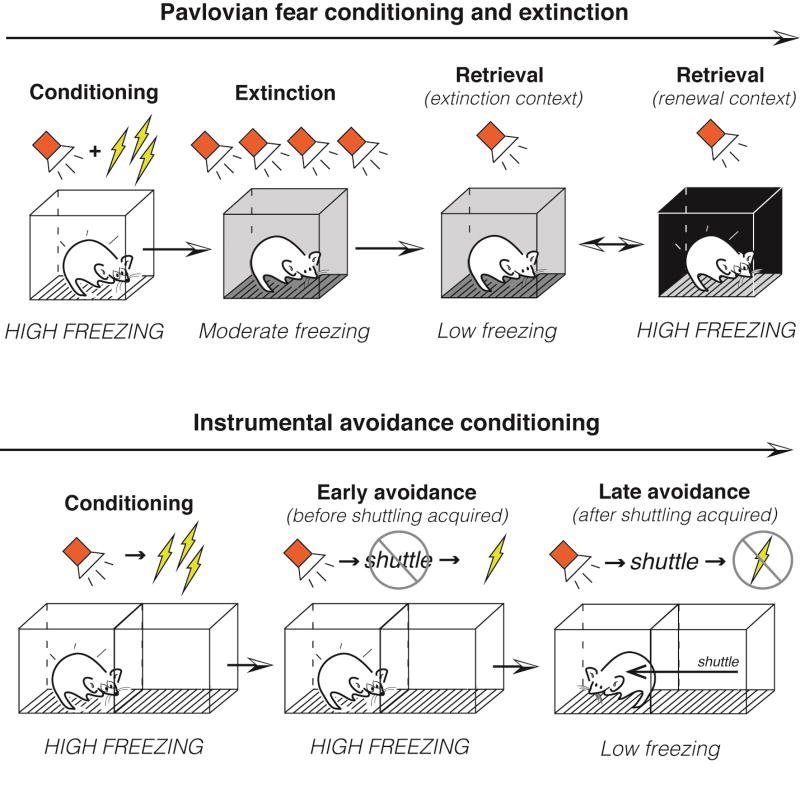

Aversive or traumatic experiences produce lifelong fear memories. But not all threats remain dangerous. Indeed, conditional fear responses can be dampened when stimuli that once predicted an aversive outcome no longer do so, a procedure (and form of learning) known as experimental extinction. Importantly, extinction is context-dependent: it is most robust at the time and in the place in which it is learned [5] (Figure 1, top). The contextual control of extinguished fear exemplifies the flexible expression of defensive behavior. In contexts in which a CS has been experienced as safe (i.e., during extinction), conditional fear is reduced; but in contexts in which it has been dangerous (or ones in which the meaning of the CS is not known), conditional fear is expressed. How does the brain generate different behavioral responses to the same CS?

Figure 1. Different forms of learning promote flexible defensive behavior.

Top: In Pavlovian fear conditioning, an auditory CS is paired with a shock US, leading to a high level of CS-evoked freezing. Extinction training occurs in a distinct environment, in which the CS is presented alone, causing a decrease in freezing. Subsequent to this training, freezing will remain low if retrieval occurs in the extinction context. However, a contextual shift will cause a renewal of freezing, demonstrating the context-dependency of extinction memory. Bottom: In active avoidance learning, the subject first undergoes a Pavlovian conditioning process in which a CS is paired with a US. This leads to a high level of CS-evoked freezing prior to the acquisition of the avoidance response (i.e. shuttling). Once shuttling is acquired, freezing is suppressed as reactive behavior is supplanted by instrumental action.

Decades of research have revealed that synaptic plasticity in the amygdala is essential for both the conditioning and extinction of defensive behaviors, including freezing [6, 7]. In particular, neurons in the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) associate CS and US information; neurons in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) in turn generate autonomic and behavioral responses associated with fear [8]. The inhibition of fear that occurs as a consequence of extinction involves the recruitment of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is anatomically positioned to inhibit amygdala outflow [9, 10]. Indeed, in both rats and humans extinguished CSs modulate mPFC activity and dampen BLA activity [11, 12].

The context-dependent expression of extinction requires the hippocampus and its interactions with the mPFC and amygdala [13]. Pharmacological inactivation of the hippocampus prevents the “renewal” of conditioned fear that normally occurs when an extinguished CS is encountered outside the extinction context [14]. Importantly, neurons in the ventral hippocampus (VH) that project to both the mPFC and the BLA are preferentially engaged during renewal [15, 16], and these dual-projecting neurons are critical for contextual memory [17]. Consistent with this, anatomical disconnection of the VH from either the mPFC or BA prevents renewal [18], as does optogenetic inhibition of VH projections to the CeA [19].

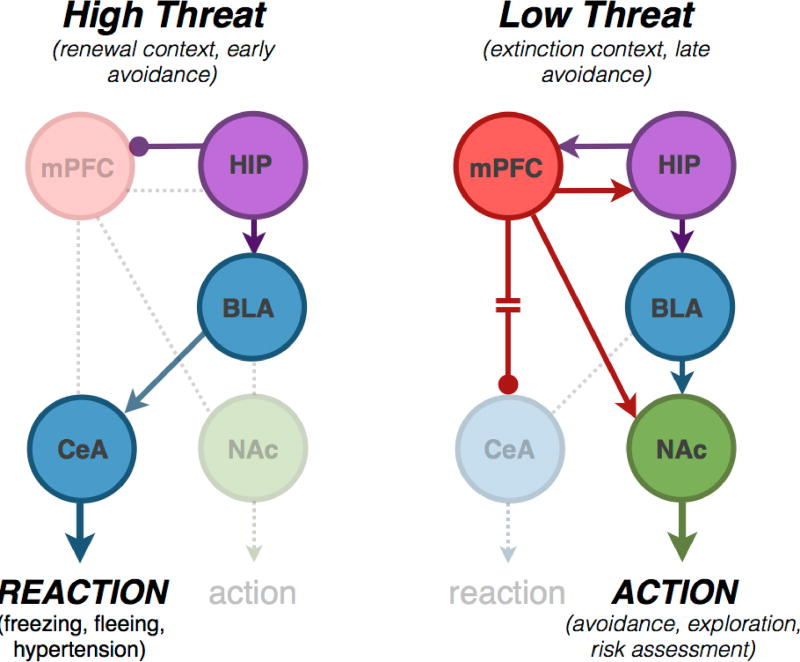

These data suggest that hippocampal and prefrontal inputs to the amygdala gate the expression of fear and extinction memories encoded by amygdala neurons (Figure 1). Consistent with this, amygdala neurons that are engaged during fear renewal receive afferent input from the hippocampus and prelimbic (PL) region of the mPFC [20]; amygdala neurons engaged during extinction retrieval receive preferential input from the infralimbic (IL) region of the mPFC [21]. In humans, functional connectivity (indexed by BOLD activity) is also increased in the hippocampus and mPFC during the renewal of extinguished fear [22, 23]. These data suggest that the hippocampus represents the meaning of a CS in a particular context , and this information biases the function of reciprocal prefrontal-amygdala circuits involved in the expression (PL) or suppression (IL) of conditional fear responses [24].

Interestingly, it has recently been shown that pairing CSs with reward during extinction (i.e., counterconditioning) or optogenetically stimulating BLA projections to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) facilitates long-term extinction [25]. This suggests that extinction not only suppresses conditioned defensive responses, but might also facilitate resumption of goal-oriented behaviors, such as exploration and food-seeking, that are normally outcompeted by defensive responses.

From freezing to avoidance

It has long been appreciated that defensive behaviors are related to the proximity or imminence of threat [26]. For example, in an ecologically valid model of defensive behavior, hungry rats forage for food under the threat of “attack” by a predatory robot [27]. When confronted by the predator, rats first flee to a safe nest box, freeze for some period of time, and then cautiously resume foraging. In this paradigm, electrical stimulation of the BLA interrupts foraging and induces fleeing [28]. BLA inactivation reduces fleeing in response to a simulated predatory attack [29], and also attenuates the expression of conditioned defensive reactions [30]. However, electrical stimulation of the BLA in a small conditioning chamber induces freezing and ultrasonic vocalization [28], indicating that the topography of BLA-dependent defensive behavior is determined, in part, by the environment. Interestingly, electrical stimulation of the periaqueductal gray (PAG), a brain area that coordinates defensive behavior [31], also induces fleeing behavior, but this effect depends on the integrity of BLA [28]. Although neuronal activity in the BLA is not coupled precisely to fleeing per se, it does correlate with behavioral decisions [32]. Together, these data indicate that the selection of particular innate defensive behaviors is underpinned by the interplay of networks spanning the amygdala and brainstem [31].

Avoidance conditioning offers another perspective on how animals use environmental information to shape flexible defensive strategies [33]. In signaled active avoidance, a specified behavior performed during a warning stimulus prevents an aversive US. In one-way avoidance procedures, the animal learns to make a unidirectional move away from danger, such as running down an alley when presented with a warning stimulus that predicts shock [34]. Recent work illustrates that fleeing can be induced in a purely Pavlovian manner. When presented with a CS made of two distinct sounds presented in sequence [35], animals will first freeze then flee. Interestingly, both freezing and fleeing require the CeA, where they are encoded by mutually inhibitory ensembles; activation of one network leads to inhibition of the other [36].

In contrast to one-way avoidance, subjects in the two-way procedure are trained to shuttle across a divided chamber in either direction in order to avoid an aversive US (Figure 1, bottom). Early in training, subjects freeze in reaction to the warning stimulus, but this response is gradually replaced by shuttling [37]. Not surprisingly, freezing to the warning stimulus competes with avoidance and animals that never overcome freezing fail to learn the avoidance contingency [38]. Importantly, CeA lesions facilitate the acquisition of shuttling and ‘rescue’ poor performers that, due to unabated freezing, do not display the avoidance response [38, 39]. Once learned, two-way avoidance depends on the serial progression of information from the BLA to the NAc [40], which is broadly implicated in instrumental processes [41]. After overtraining of instrumental avoidance, the contribution of the BLA to avoidance performance wanes [42, 43], an outcome that does not occur in Pavlovian fear conditioning [44].

Recent work has revealed that the transition from freezing to avoidance depends upon a neurocircuitry that dampens CeA-dependent freezing behavior (Figure 2). Inactivation of the IL, for example, attenuates avoidance learning and promotes freezing to the warning stimulus [45]. Hence, the transition from freezing to avoidance may depend on mPFC circuits that toggle between amygdalar output pathways, from brainstem-projecting neurons in CeA that underpin freezing to ventral striatum-projecting neurons in BLA that underpin shuttling. In contrast, animals that fail to recruit the mPFC, such as when they are submitted to inescapable shock, exhibit ‘learned helplessness’ and show exaggerated fear responses to shock-paired CSs [46]. Thus, the suppression of freezing may be related to the controllability of aversive stimuli in the avoidance paradigm.

Figure 2. Neural pathways regulating flexible defensive behavior.

Arrows are not synapse specific, but instead represent the flow of information and the net excitatory or inhibitory effect of the schematized inputs. Left: Relatively inflexible reactions to highly threatening cues, such as freezing, fleeing and hypertension, are mediated by the central amygdala (CeA), which receives substantial input from the basolateral amygdala (BLA). The exact nature of the response to a threat can be determined by salient contextual stimuli, such as the topography of the environment, which may be passed to the amygdala through inputs from the hippocampus (HIP). HIP projections also play a key role in causing the return of previously suppressed defensive reactions caused by contextual shifts (i.e. renewal). Right: Flexibility increases in response to lower intensity threats, which leads to the recruitment of circuits spanning HIP and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) that regulate amygdalar processing. mPFC inhibits innate reactions via an indirect connection with CeA. This facilitates behaviors like exploration and avoidance, which require BLA projections to nucleus accumbens (NAc). mPFC also projects to NAc, and this convergent input to NAc is crucial for flexible defensive actions.

In this regard, different subregions of mPFC may play distinct roles in avoidance. In a paradigm that requires subjects to step onto a platform to avoid a cued shock, inactivation of IL increases freezing [47], as in the two-way procedure. However, increased freezing does not impede avoidance in this experimental setup, which is designed to dissociate these behaviors. Inactivation of PL produces a complementary pattern of effects, attenuating platform avoidance without producing a substantial effect on freezing [47]. Although permanent lesions of PL produce no effect on two-way avoidance [45], temporary inactivation studies of platform avoidance suggest that the suppression of conflicting reactions and the production of the avoidance response are mediated by dissociable neocortical circuits in IL and PL mPFC, respectively.

Finally, considerable evidence implicates the hippocampus in avoidance learning [48]. In general, hippocampal lesions impair one-way avoidance, but facilitate two-way active avoidance learning. This pattern of results is thought to occur because hippocampal lesions impair contextual fear conditioning, thereby limiting freezing behavior that opposes avoidance learning [49]. Interestingly, recent data indicate that pharmacological inactivation of either dorsal hippocampus (DH) or ventral hippocampus (VH) interfere with the acquisition of signaled twoway active avoidance [50]. While the effect of DH inactivation may suggest a novel role of hippocampal circuits in avoidance, VH inactivation has been shown to impair auditory fear conditioning [51], and this may account for impairments in avoidance learning caused by this manipulation. Clearly, more research is needed to clarify the role of the hippocampus in avoidance.

Bringing fear under control

Although there is a cadre of innate behaviors for contending with threat, the form and intensity of these responses can be adaptively regulated. As we have described, some contingencies, such as Pavlovian extinction or instrumental conditioning, can lead to flexible expression of defensive behavior in response to threatening cues. Of course, the capacity to behave flexibly in the face of fear ensures that animals are not “once bitten, twice shy”. Indeed, the failure to regulate fear and defense in a context-appropriate manner is believed to contribute to the maintenance of anxiety disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [13, 52].

Here we propose that hippocampal-prefrontal projections to the amygdala and nucleus accumbens form a critical neural circuit for regulating behavioral reactions to threatening cues (Figure 2). Ultimately, this circuit allows for the expression of defensive behaviors that are adaptively calibrated to changing threats. For example, in Pavlovian extinction, animals learn that a once dangerous CSs no longer results in aversive outcomes and conditional freezing comes under contextual control. In active avoidance, animals learn that an aversive outcome can in fact be prevented, and conditional freezing is supplanted by the avoidance response. In both cases, animals form CS-US and CS-‘no-US’ associations that can be disambiguated by context. In Pavlovian extinction, the CS-‘no-US’ association is imposed in a unique environment, whereas in instrumental avoidance that contingency is experienced when the animal makes a successful avoidance response. Thus, the cognitive context of instrumental control may retrieve an extinction contingency and limit freezing in much the same way that the external environment gates freezing following extinction.

Alternatively, while extinction may tie the expression of defensive behavior to external contexts, avoidance may alter the response to threatening cues by bringing aversive outcomes under behavioral control. If so, then it may be the case that avoidance learning leads the animal to re-categorize the warning stimulus, transforming it from a Pavlovian CS that predicts danger to a discriminative stimulus that signifies an opportunity for instrumental action. This process may require suppression of the Pavlovian representation and/or responses like freezing (which conflict with the avoidance response), and thus the engagement of circuits that regulate defensive behavior.

Ultimately, hippocampal-prefrontal circuits index the meaning of events to the defensive scenarios in which they occur. This allows defensive behavior to move off the “performance line” [53] and come under contextual and/or instrumental control. We believe that this process is critical for adaptive emotional regulation and, of course, adaptive defensive behavior. Consistent with animal studies, work on escape and avoidance behavior in humans demonstrates that control over an aversive US attenuates the arousal evoked by warning stimuli [54] and fMRI work shows that these behaviors recruit the mPFC [55]. The substrates that promote flexibility in the face of fear may be homologous across mammalian species, suggesting that regulatory mechanisms discovered in animals can suggest targets for novel therapeutics in humans suffering from disorders of fear and anxiety.

Highlights.

Defensive behaviors are adaptive, but failure to regulate their expression can become pathological.

The contextual control of fear extinction and acquisition of instrumental avoidance are examples of flexible expressions of behavior under threat.

The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex regulate fear reactions and instrumental actions by through the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the NIH (R01MH065961) a McKnight Memory and Cognitive Disorders Award to SM and a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Award to JMM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanselow MS, Wassum KM. The Origins and Organization of Vertebrate Pavlovian Conditioning. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2016;8 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolles R. Species-specific defense reactions and avoidance learning. Psychol Rev. 1970;77:32–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouton ME, Westbrook RF, Corcoran KA, Maren S. Contextual and temporal modulation of extinction: Behavioral and biological mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maren S, Quirk GJ. Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:844–852. doi: 10.1038/nrn1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herry C, Johansen JP. Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/nn.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jimenez SA, Maren S. Nuclear disconnection within the amygdala reveals a direct pathway to fear. Learn Mem. 2009;16:766–768. doi: 10.1101/lm.1607109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quirk G, Mueller D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giustino TF, Maren S. The Role of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in the Conditioning and Extinction of Fear. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015;9:758–20. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milad M, Quirk G. Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: ten years of progress. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:129–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •12.Lonsdorf TB, Haaker J, Kalisch R. Long-term expression of human contextual fear and extinction memories involves amygdala, hippocampus and ventromedial prefrontal cortex: a reinstatement study in two independent samples. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:1973–1983. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu018. This report reveals overlapping neural circuits in the human brain involved in the regulation of extinguished fear responses. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex exhibits greater BOLD signals during fear suppression, whereas that in the hippocampus increases during fear renewal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maren S, Phan KL, Liberzon I. The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:417–428. doi: 10.1038/nrn3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corcoran KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts contextual retrieval of fear memory after extinction. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1720–1726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01720.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •15.Jin J, Maren S. Fear renewal preferentially activates ventral hippocampal neurons projecting to both amygdala and prefrontal cortex in rats. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8388. doi: 10.1038/srep08388. This study demonstrates that neurons in the ventral hippocampus that project to both the mPFC and the BLA participate in the renewal of fear after extinction. These dual-projecting neurons may synchronize activity in prefrontal-amygdala networks involved in contextual control of defensive behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, Jin J, Maren S. Renewal of extinguished fear activates ventral hippocampal neurons projecting to the prelimbic and infralimbic cortices in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WB, Cho J-H. Synaptic Targeting of Double-Projecting Ventral CA1 Hippocampal Neurons to the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Basal Amygdala. J Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orsini CA, Kim JH, Knapska E, Maren S. Hippocampal and prefrontal projections to the basal amygdala mediate contextual regulation of fear after extinction. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17269–17277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4095-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •19.Xu C, Krabbe S, Gründemann J, Botta P, Fadok JP, Osakada F, Saur D, Grewe BF, Schnitzer MJ, Callaway EM, et al. Distinct Hippocampal Pathways Mediate Dissociable Roles of Context in Memory Retrieval. Cell. 2016;167:961. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.051. This report uses circuit-specific targeting manipulations to dissociate the contribution of ventral hippocampal projections to the CeA and BLA in fear renewal and contextual memory, respectively. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapska E, Macias M, Mikosz M, Nowak A, Owczarek D, Wawrzyniak M, Pieprzyk M, Cymerman IA, Werka T, Sheng M, et al. Functional anatomy of neural circuits regulating fear and extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17093–17098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202087109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herry C, Ciocchi S, Senn V, Demmou L, Müller C, Lüthi A. Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature. 2008;454:600–606. doi: 10.1038/nature07166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Åhs F, Kragel PA, Zielinski DJ, Brady R, Labar KS. Medial prefrontal pathways for the contextual regulation of extinguished fear in humans. Neuroimage. 2015;122:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermann A, Stark R, Milad MR, Merz CJ. Renewal of conditioned fear in a novel context is associated with hippocampal activation and connectivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11:1411–1421. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knapska E, Maren S. Reciprocal patterns of c-Fos expression in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala after extinction and renewal of conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2009;16:486–493. doi: 10.1101/lm.1463909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••25.Correia SS, McGrath AG, Lee A, Graybiel AM. Amygdala-ventral striatum circuit activation decreases long-term fear. eLife. 2016 doi: 10.7554/elife.12669. This report reveals a novel role for projections from the basolateral amygdala to the nucleus accumbens in the acquisition of fear extinction. It suggests that extinction might involve not only fear reduction, but also renewed reward-seeking. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fanselow MS, Lester LS. A functional behavioristic approach to aversively motivated behavior: Predatory imminence as a determinant of the topography of defensive behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellman BA, Kim JJ. What Can Ethobehavioral Studies Tell Us about the Brain's Fear System? Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim EJ, Horovitz O, Pellman BA, Tan LM, Li Q, Richter-Levin G, Kim JJ. Dorsal periaqueductal gray-amygdala pathway conveys both innate and learned fear responses in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14795–14800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310845110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••29.Choi J-S, Kim JJ. Amygdala regulates risk of predation in rats foraging in a dynamic fear environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21773–21777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010079108. This report explores the contribution of the amygdala to defensive behaviors engaged in a seminaturalistic situation with a robot predator. It reveals that the dominant response of rats to an artificial predators is fleeing and avoidance, both of which require the amygdala. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helmstetter F, Bellgowan P. Effects of muscimol applied to the basolateral amygdala on acquisition and expression of contextual fear conditioning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:1005–1009. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tovote P, Esposito MS, Botta P, Chaudun F, Fadok JP, Markovic M, Wolff SBE, Ramakrishnan C, Fenno L, Deisseroth K, et al. Midbrain circuits for defensive behaviour. Nature. 2016;534:206–212. doi: 10.1038/nature17996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amir A, Lee S-C, Headley DB, Herzallah MM, Paré D. Amygdala Signaling during Foraging in a Hazardous Environment. J Neurosci. 2015;35:12994–13005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0407-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeDoux JE, Moscarello J, Sears R, Campese V. The birth, death and resurrection of avoidance: a reconceptualization of a troubled paradigm. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017;22:24–36. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olton DS. Shock-motivated avoidance and the analysis of behavior. Psychol Bull. 1973;79:243–251. doi: 10.1037/h0033902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Oca BM, Minor TR, Fanselow MS. Brief Flight to a Familiar Enclosure in Response to a Conditional Stimulus in Rats. The Journal of General Psychology. 2007;134:153–172. doi: 10.3200/GENP.134.2.153-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••36.Fadok JP, Krabbe S, Markovic M, Courtin J, Xu C, Massi L, Botta P, Bylund K, Müller C, Kovacevic A, et al. A competitive inhibitory circuit for selection of active and passive fear responses. Nature. 2017;542:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature21047. This study reveals an important role for CeA networks for organizing both freezing and fleeing behavior to aversive CSs. It is shown that competing inhibitory networks in the CeA engage different behavioral responses depending on the temporal proximity of threat. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mineka S. The Role of Fear in Theories of Avoidance-Learning, Flooding, and Extinction. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:985–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi J-S, Cain CK, LeDoux JE. The role of amygdala nuclei in the expression of auditory signaled two-way active avoidance in rats. Learn Mem. 2010;17:139–147. doi: 10.1101/lm.1676610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lázaro-Muñoz G, LeDoux JE, Cain CK. Sidman Instrumental Avoidance Initially Depends on Lateral and Basal Amygdala and Is Constrained by Central Amygdala-Mediated Pavlovian Processes. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramirez F, Moscarello JM, LeDoux JE, Sears RM. Active Avoidance Requires a Serial Basal Amygdala to Nucleus Accumbens Shell Circuit. J Neurosci. 2015;35:3470–3477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1331-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbit LH, Balleine BW. Behavioral Neuroscience of Motivation. Springer International Publishing; 2015. Learning and Motivational Processes Contributing to Pavlovian–Instrumental Transfer and Their Neural Bases: Dopamine and Beyond; pp. 259–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poremba A, Gabriel M. Amygdala neurons mediate acquisition but not maintenance of instrumental avoidance behavior in rabbits. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9635–9641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09635.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maren S, Poremba A, Gabriel M. Basolateral amygdaloid multi-unit neuronal correlates of discriminative avoidance learning in rabbits. 1991;549:311–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90473-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maren S. Overtraining does not mitigate contextual fear conditioning deficits produced by neurotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3088–3097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03088.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •45.Moscarello JM, LeDoux JE. Active Avoidance Learning Requires Prefrontal Suppression of Amygdala-Mediated Defensive Reactions. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3815–3823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2596-12.2013. This report demonstrates a critical role for the medial prefrontal cortex in the regulation of signaled avoidance conditioning by inhibiting amygdala-dependent fear responses that compete with avoidance responding. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maier SF, Seligman MEP. Learned Helplessness at Fifty: Insights From Neuroscience. Psychol Rev. 2016;123:349–367. doi: 10.1037/rev0000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bravo-Rivera C, Roman-Ortiz C, Brignoni-Perez E, Sotres-Bayon F, Quirk GJ. Neural structures mediating expression and extinction of platform-mediated avoidance. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9736–9742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0191-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwarting RKW, Busse S. Behavioral facilitation after hippocampal lesion: A review. Behav Brain Res. 2017;317:401–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olton DS, Isaacson RL. Hippocampal Lesions and Active Avoidance. Physiol Behav. 1968;3:719. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Bast T, Wang Y-C, Zhang W-N. Hippocampus and Two-Way Active Avoidance Conditioning: Contrasting Effects of Cytotoxic Lesion and Temporary Inactivation. Hippocampus. 2015;25:1517–1531. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maren S, Holt WG. Hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: Muscimol infusions into the ventral, but not dorsal, hippocampus impair the acquisition of conditional freezing to an auditory conditional stimulus. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:97–110. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liberzon I, Abelson JL. Context Processing and the Neurobiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Neuron. 2016;92:14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirsh R. The hippocampus and contextual retrieval of information from memory: a theory. Behavioral Biology. 1974;12:421–444. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(74)92231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartley CA, Gorun A, Reddan MC, Ramirez F, Phelps EA. Stressor controllability modulates fear extinction in humans. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014;113:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boeke EA, Moscarello J, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA, Hartley CA. Active avoidance: Neural mechanisms and attenuation of Pavlovian conditioned responding. J Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3261-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]