Summary

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (UNE) is the second most frequent compression neuropathy. While other diagnostic imaging tools are emerging to assist in the diagnosis of UNE, electrodiagnosis remains the gold standard. However, the electrodiagnostic approach to UNE presents unique challenges limiting its diagnostic accuracy. We review advances in 5 areas relevant to the diagnosis of UNE: technologic advancements with modern EMG machines have allowed for reconsideration of the question of experimental error and lesion detection; how temperature effects can lead to misdiagnosis; the effect of body mass index on the electrodiagnosis of UNE; the validation of short segment studies; and the emerging role of high-resolution sonography as a diagnostic tool.

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (UNE) is the second most common compression neuropathy after carpal tunnel syndrome, yet presents a much more complex challenge for the clinician in terms of its clinical evaluation, electrodiagnostic picture, and management. Electrodiagnosis of the ulnar nerve at the elbow is not nearly as straightforward as that of the median nerve at the wrist. The diagnostic yield is less and the interpretations of the data often more difficult secondary to unique challenges related to technical factors. Technical errors continue to present a major source of misdiagnosis and UNE has been referred to as the EMGers nightmare. This article reviews 5 recent advancements related to the diagnosis of UNE.

The 10-cm rule has outlived its usefulness

Most aspiring electromyographers learn early in training the 10-cm rule: nerve conduction studies (NCS) across the elbow or across the knee should not be done at a distance of less than 10 cm. This rule arose because of a historic article published in 1972 by Maynard and Stolov.1 These investigators were interested in the experimental error inherent in performing NCS. They used 20 electromyographers to gather data on latency and distance measurement determination variability. They used for latency determination variability the state-of-the-art equipment available at the time: a TECA model B-2 electromyograph. The technology of the era involved using a Polaroid camera to capture the sweep on photosensitive paper, then measuring the latency by hand with a metal ruler. To assess distance measurement variability, they had the electromyographers measure the distance between 2 lines on a plank. After collecting all the measurements, they calculated experimental error using a mathematically derived formula, then constructed families of error curves relating both conduction velocity (CV) and distance. The article contains large tables relating percentage of error to CV and distance. Nowhere in the article do the authors make a specific recommendation about minimal acceptable distance. But there is a single remark in the discussion: “the error in conduction velocity when…distances of 100 mm or less are used is very high, well over 10 m/s for all velocities of 40 m/s or more. This would represent a potential 25% error and is certainly unacceptable.” This statement was the birth of the 10-cm rule. After this article, electromyographers universally adopted a 10-cm minimum distance for doing all ulnar motor NCS across the elbow and peroneal motor NCS across the fibular head. This teaching was not challenged for 30 years.

Maynard and Stolov did not set out to establish a minimum distance for performing NCS; they set out to study experimental error. They made a plea for better methods for determining latency. Electromyographic equipment improved considerably after the B-2, which was a relatively primitive machine. Certainly by 2003, it was time to revisit the experimental error question.

In 2003, Landau et al.2 repeated the Maynard and Stolov study using modern equipment. Twenty electromyographers measured the latency of the same stored compound muscle action potential (CMAP). The distance was measured between 2 marks on the forearm of a human volunteer. Identical calculations were performed. Again experimental error increased as distance decreased, reaching 20% with distances less than 6 cm. Maynard and Stolov had found an error of 25% at a distance of 10 cm. So with the current generation of equipment, the experimental error at 6 cm is roughly equivalent to that at 10 cm 30 years ago. Latency error accounted for 71% of the total experimental error as opposed to 90% in 1972. The equipment has improved a great deal, and the experimental error inherent in the nerve conduction technique has dropped considerably. We can now perform NCS at shorter distances with the same experimental error than in the past.

Ulnar studies around the elbow are very difficult. The curvilinear distance measurement is much more prone to error than the straight line distance measured along the forearm. Another critical factor is the nature of focal neuropathies. Brown et al.,3 doing intraoperative studies, showed that the focal demyelination in UNE typically involves a very short segment of the nerve, usually 5–10 mm. The greater the number of normally conducting segments proximal and distal to the diseased segment that are included with the conduction study, the less the likelihood the overall CV will fall outside the normal range. This is the dilution effect. The dilemma is that measurements over longer distances decrease the experimental error but measurements over shorter distances result in a greater chance of detecting such lesions. The problem is that missing the lesion is also an error—a type II, or false-negative error. So, for decades, in their zeal to avoid experimental error, electromyographers have been making the type II error by steadfastly performing distances over no less than 10 cm. One result has been that EMG has earned a reputation as relatively insensitive in the diagnosis of UNE. Many surgeons do not think it is useful in the workup of such patients and rely on their clinical impression regarding when to perform surgery.

In 2003, Landau et al.4 published another article specifically looking at the optimal screening distance for performing ulnar studies across the elbow using a lesion model that incorporated the increased experimental error for the curvilinear distance measurement around the elbow as well as introducing a lesion into model nerves conducting at various CVs. They calculated the total error as the sum of both false-negative and false-positive percentages. The aim was to look at both the type I and type II errors and define the distance that achieved the optimal compromise that avoided experimental error but still permitted detection of the lesion. They concluded that the optimal distance for screening for UNE, considering both sensitivity and specificity, is significantly less than 10 cm, perhaps as low as 4–6 cm.

Another consideration is the likely location of focal lesions in the region of the elbow. Most pathology at the elbow occurs between 3 cm proximal and 3 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. With this additional consideration the conclusion was that the optimal distance for screening for UNE was 6 cm. Using similar reasoning, i.e., trying to minimize the total error, van Dijk et al.5 concluded that the least total error occurred at a distance of 50 mm, but because of a compromise to include the likely locations of pathology recommended doing ulnar NCS at 8 cm.

Cold elbow syndrome

The questions and premises that led to the establishment of the cold elbow syndrome were the following: (1) low temperature decreases nerve conduction velocity (NCV), (2) the across-elbow segment of the ulnar nerve is superficial and might be particularly susceptible to decreased temperature, and (3) some cases of decreased across-elbow CV occur unexpectedly during the course of routine conduction studies for patients who have no ulnar complaints; could these be due to low temperature?

A study was done to investigate whether decreased temperature at the elbow could be responsible for some of these unexpected cases of across-elbow slowing during routine studies in patients without ulnar complaints.6 Two groups of patients were studied. One group had no ulnar complaints but had isolated across-elbow slowing with otherwise normal ulnar conduction studies, including the ulnar sensory potential (normal group). The other were patients with clinical and electrodiagnostic findings of UNE. All had ulnar motor NCS completed before and after elbow warming. The mean across-elbow NCV were 43 m/s and 49 m/s in the normal group (p < 0.0001) and 37 m/s and 38 m/s (p = 0.90) in the UNE group, before and after warming, respectively. In the normal group, 17 of 32 subjects had normal studies after warming. No patient with UNE developed normal NCV after warming.

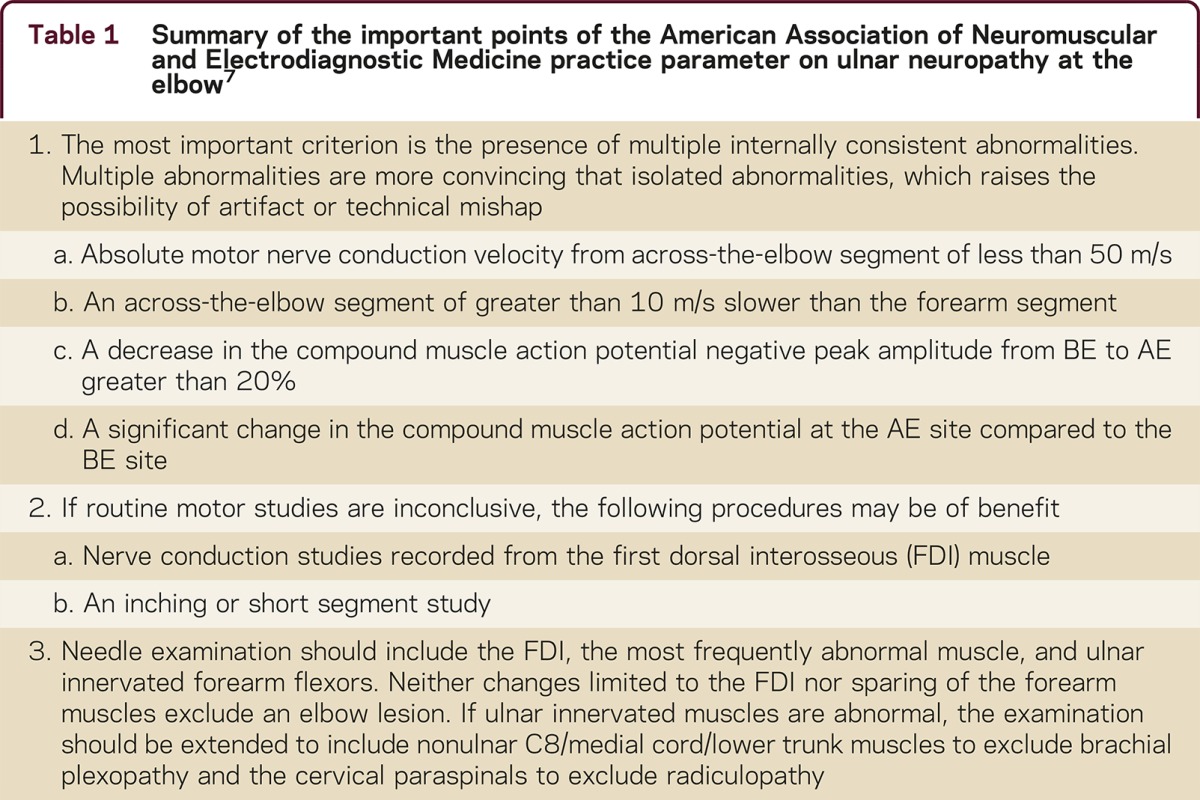

This study demonstrates that a cold elbow may cause spuriously slow CV simulating UNE. Electromyographers should be wary of isolated across-elbow slowing as the only manifestation of UNE. Warming the elbow and repeating the study will make the abnormality disappear in many cases. In no instance did slowing due to a bona fide UNE disappear with warming. This reinforces the most important recommendation of the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) ulnar practice parameter for UNE: insist on multiple internally consistent abnormalities7 (table 1).

Table 1 Summary of the important points of the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine practice parameter on ulnar neuropathy at the elbow7

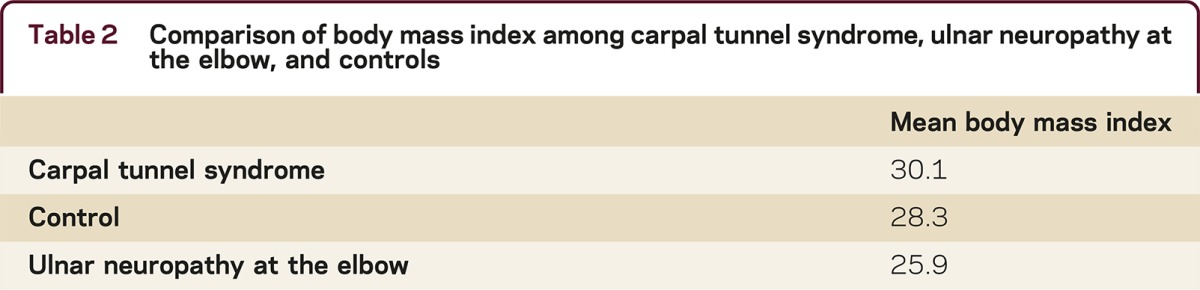

Skinny elbow syndrome

A high body mass index (BMI) has been consistently linked to increased risk for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). The literature on the relationship between BMI and UNE has been contradictory. To look into this issue further, the BMI was calculated for 50 patients with a sole diagnosis of UNE and compared to the BMI of 50 CTS patients and 50 controls (table 2).8 The mean BMIs were 25.9 ± 4, 30.1 ± 5.5, and 28.3 ± 5.6 for the UNE, CTS, and controls, respectively. By one-way analysis of variance, the difference in BMI between the UNE patients and the normal patients was significant (p < 0.01), suggesting that relatively slender patients are at risk for developing UNE, perhaps related to less protective adipose tissue.

Table 2 Comparison of body mass index among carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, and controls

Measurement of across-elbow ulnar NCV in asymptomatic individuals is also affected by weight. Ulnar motor CVs may be falsely increased in patients with high BMI because of distance measurement factors. Rounder elbows are more likely to have a skin distance to nerve distance mismatch that leads to an overestimation of NCV; increased temperature may be a contributory factor because of more adipose tissue. The skinny elbow syndrome describes the following conundrum. Slender patients are at increased risk of developing UNE. Slender patients also have relatively slower ulnar NCS because of the closer match between skin distance and nerve distance. There is less margin for error and extra care is required to avoid overdiagnosis. Additionally, the electrodiagnostician must be wary of overstimulation, which may result in undesirable distant nerve stimulations and incorrectly short latencies. There must be closer attention to technical detail. It is possible that such patients may also have an increased susceptibility to the cold elbow syndrome, but this has not been verified.

Utility of short segment studies has been validated

The AANEM defines inching as a NCS technique wherein stimulus applications at multiple short distance increments along the course of a nerve are performed to localize an area of focal slowing or conduction block. In fact, there are 2 types of short segment studies (SSS) or short segment incremental studies (SSIS). The term inching was introduced by Miller in 19799 to refer to the technique of moving the stimulator along the nerve in several sequential steps in search of points of abrupt change in CMAP amplitude or configuration indicative of conduction block or differential slowing due to underlying focal demyelination at the humeroulnar arcade in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome. SSS had been done as early as 1963.10 Kimura,11 also in 1979, introduced the technique of 1-cm SSS for CTS. Kimura was later fond of referring to the studies as “centimetering” rather than inching.

Kanakamedala et al.12,13 used 2-cm segments to study UNE and peroneal neuropathy at the knee and found marked abnormalities across discrete segments. In 1988, Campbell et al.14 studied 1-cm segments intraoperatively and, in 1992,15 found excellent correlation between 1-cm percutaneous SSIS and abnormalities demonstrated by direct epidural stimulation intraoperatively in patients with UNE. The correlation was approximately 80%.

The use of SSS has become widespread in the last 20 years, but only in the last 8–10 years has there been independent validation of their utility in UNE. In 2003, Azrieli et al.16 used 2-cm SSIS in 21 patients with signs and symptoms of UNE and a found sensitivity of 81% compared to 24% using an across-the-elbow CV with a 10–14 cm segment. These results further validated that SSS significantly improve detection of UNE and should be considered when routine studies are negative and clinical suspicion remains high. Beyond increasing detection rate, SSIS provides further usefulness in confirming localization of the underlying lesion, particularly when routine studies leave uncertainty about the diagnosis of UNE. In 2005, Visser,17 in a large, well-done study, provided further validation of the diagnostic value of SSIS in the evaluation of UNE. In this study, SSIS had an additional localizing value in 76% of the patients with isolated NCV slowing across the elbow or with nonlocalizing electrodiagnostic findings. Both of these studies confirm that SSIS is a useful and simple method that provides additional diagnostic value, both in terms of increasing detection rate as well as confirming localization, and should be considered in all evaluations of UNE.

High-resolution sonography is emerging as a useful tool

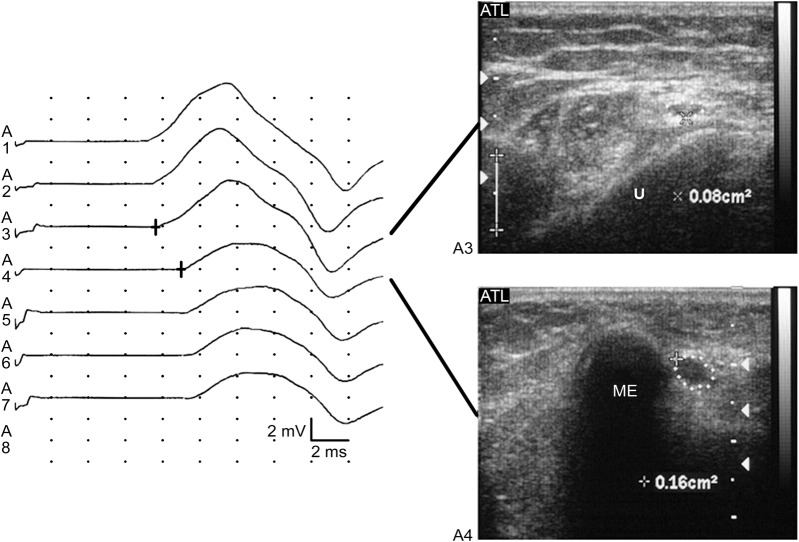

Dramatic advances in ultrasound technology now allow the visualization of peripheral nerves, and a great deal has been written about the utility of high-resolution sonography (HRS) in the diagnosis and management of UNE (figure). The biologic response to nerve compression consists of a cascade of pathologic changes, to include thickening of the walls of endoneurial and perineurial microvessels; thickening of the endoneurium because of edema; an increase in the amount of connective tissue; and later, thickening of the epineurium and perineurium due to fibrosis and edema.18,19 Correlating with these pathologic changes, abnormal ultrasound findings in compressive neuropathies include an increased cross-sectional area, loss of normal echotexture, and increased nerve vascularity. In a 2011 systemic review,20 the authors found 7 of 11 clinical trials of HRS in UNE suitable for further analysis. They found that ulnar nerve size measurement appears to have good diagnostic accuracy and that the most frequently reported abnormality was increased cross-sectional area. The conclusion was that the role of HRS was promising but could not be firmly established and that more prospective studies were needed. It should be pointed out that the sensitivity and specificity of HRS has only been compared to standard, 10-cm traditional across-elbow ulnar conduction studies. This is the equivalent of comparing 2013 ultrasound with 1972 EMG. There have been no studies comparing HRS with the best techniques currently available in the electromyographer's toolbox, such as SSIS.

High-resolution ultrasound of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow

Figure. On the left, short segment incremental studies demonstrate an area of focal slowing and partial conduction block at the A4 segment, which corresponds to the area of the ulnar groove (line between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon). On the right, axial ultrasound images of the ulnar nerve corresponding with these positions is shown. The upper image demonstrates the nerve distal to the ulnar groove, while the lower image shows the approximation of the nerve to the medial epicondyle in the ulnar groove. Note the doubling of the cross-sectional area of the nerve (dots) over this distance, from 0.08 cm2 to 0.16 cm2. Reprinted with permission from Caress JB, Becker CE, Cartwright MS, Walker FO. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2003;4:161.

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: Five new things

The 10-cm rule has outlived its usefulness. Technological advancements with modern EMG machines have allowed for reconsideration of the 10-cm rule, requiring a 10-cm distance between the above and below the elbow stimulation sites. Distances as short as 6 cm may be optimal.

An abnormally low temperature across the elbow may spuriously slow CV simulating UNE.

Ulnar motor CVs may be falsely increased in patients with high BMI because of distance measurement factors. Slender patients are at risk for developing UNE, perhaps related to less protective adipose tissue.

The SSS, or inching study, has been validated as a useful and simple method that provides additional diagnostic value, both in terms of increasing detection rate as well as confirming localization, and should be considered in all evaluations of UNE.

High-resolution sonography has emerged as an accurate diagnostic tool in the evaluation of UNE showing an increased cross-sectional area at the site of compression. This technology may prove to be as sensitive and specific as currently accepted electrodiagnostics.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

W.W. Campbell receives publishing royalties for DeJong's The Neurologic Examination, 7th ed. (Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012) and Essentials of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 2nd ed. (Demos, 2013). C.G. Carroll and M. Landau report no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

Correspondence to: craig.g.carroll.mil@mail.mil

* These authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Correspondence to: craig.g.carroll.mil@mail.mil

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maynard FM, Stolov WC. Experimental error in determination of nerve conduction velocity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1972;53:362–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landau ME, Diaz MI, Barner KC, Campbell WW. Optimal distance for segmental nerve conduction studies revisited. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:367–369. doi: 10.1002/mus.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown WF, Ferguson GG, Jones MW, Yates SK. The location of conduction abnormalities in human entrapment neuropathies. Can J Neurol Sci. 1976;3:111–122. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100025865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landau ME, Barner KC, Campbell WW. Optimal screening distance for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:570–574. doi: 10.1002/mus.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk JG, Meulstee J, Zwarts MJ, Spaans F. What is the best way to assess focal slowing of the ulnar nerve? Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:286–293. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landau ME, Barner KC, Murray ED, Campbell WW. Cold elbow syndrome: spurious slowing of ulnar nerve conduction velocity. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:815–817. doi: 10.1002/mus.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Guidelines in electrodiagnostic medicine: practice parameter for electrodiagnostic studies in ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve Suppl 1999;8:S171–S205. [PubMed]

- 8.Landau ME, Barner KC, Campbell WW. Effect of body mass index on ulnar nerve conduction velocity, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:360–363. doi: 10.1002/mus.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RG. The cubital tunnel syndrome: diagnosis and precise localization. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:56–59. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaeser HE. Erregungsleitungsstorungen bei ulnarlsparesen [in German] Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd. 1963;185:231–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura J. The carpal tunnel syndrome: localization of conduction abnormalities within the distal segment of the median nerve. Brain. 1979;102:619–635. doi: 10.1093/brain/102.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanakamedala RV, Simons DG, Porter RW, Zucker RS. Ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow localized by short segment stimulation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:959–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanakamedala RV, Hong CZ. Peroneal nerve entrapment at the knee localized by short segment stimulation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;68:116–122. doi: 10.1097/00002060-198906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell WW, Sahni SK, Pridgeon RM, Riaz G, Leshner RT. Intraoperative electroneurography: management of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:75–81. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell WW, Pridgeon RM, Sahni KS. Short segment incremental studies in the evaluation of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:1050–1054. doi: 10.1002/mus.880150910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azrieli Y, Weimer L, Lovelace R, Gooch C. The utility of segmental nerve conduction studies in ulnar mononeuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:46–50. doi: 10.1002/mus.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser LH, Beekman R, Franssen H. Short-segment nerve conduction studies in ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:331–338. doi: 10.1002/mus.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beekman R, Visser LH, Verhagen WI. Ultrasonography in ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: a critical review. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:627–635. doi: 10.1002/mus.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prinz RA, Nakamura-Pereira M, De-Ary-Pires B. Axonal and extracellular matrix responses to experimental chronic nerve entrapment. Brain Res. 2005;1044:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker F, Cartwright M. Neuromuscular Ultrasound. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011.