Summary

The practice of medicine relies on the patient–physician relationship, knowledge, and clinical judgment. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the least biased method for studying the effects of interventions in selected populations and are the only method to control adequately for unknown confounders. However, physicians face the limitations of RCTs on a daily basis as they treat relatively unselected populations and individual patients. We explore the benefits and limitations of RCTs for some neurologic disorders, and discuss the difficulties of predicting individualized outcomes and anticipating treatment responses in those heterogeneous conditions. Observational studies and advances in understanding neurologic diseases complement RCTs in decision-making. Considerable challenges remain for personalized medicine; for now, clinicians must rely on their ability to integrate evidence and clinical judgment.

In the past, the practice of medicine was considered an art. Modern developments have pushed forward the science of medicine and promoted ideas of algorithmic approaches that leave less room for personalized interpretations. Standardized protocols and guidelines are increasingly endorsed in diagnosis and treatment, with the view that these initiatives raise the quality of care by optimizing resources and minimizing risks.

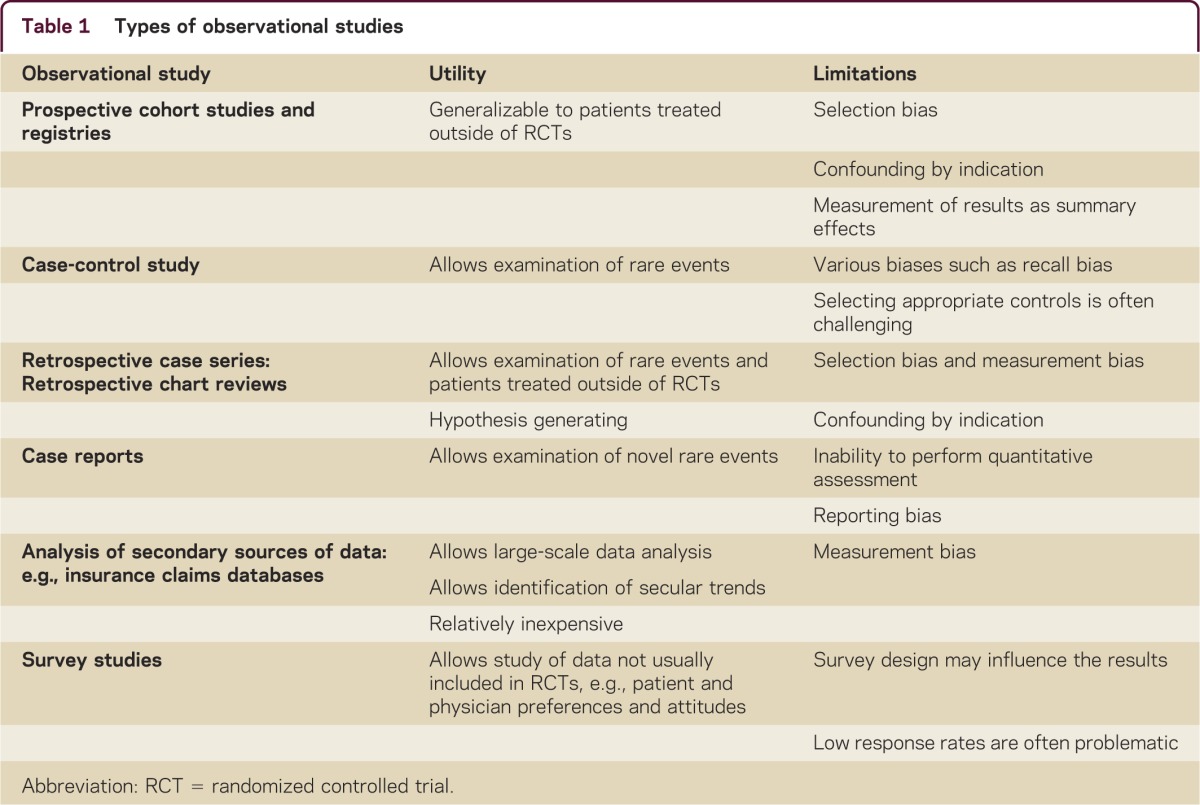

In this article, we present examples from multiple sclerosis (MS) and other neurologic conditions to highlight the importance of understanding the natural history of treatment-naive patients and the clinical course on treatment through observational studies, which have been transforming the practice of medicine alongside randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (table 1).

Table 1 Types of observational studies

Evidence-based medicine

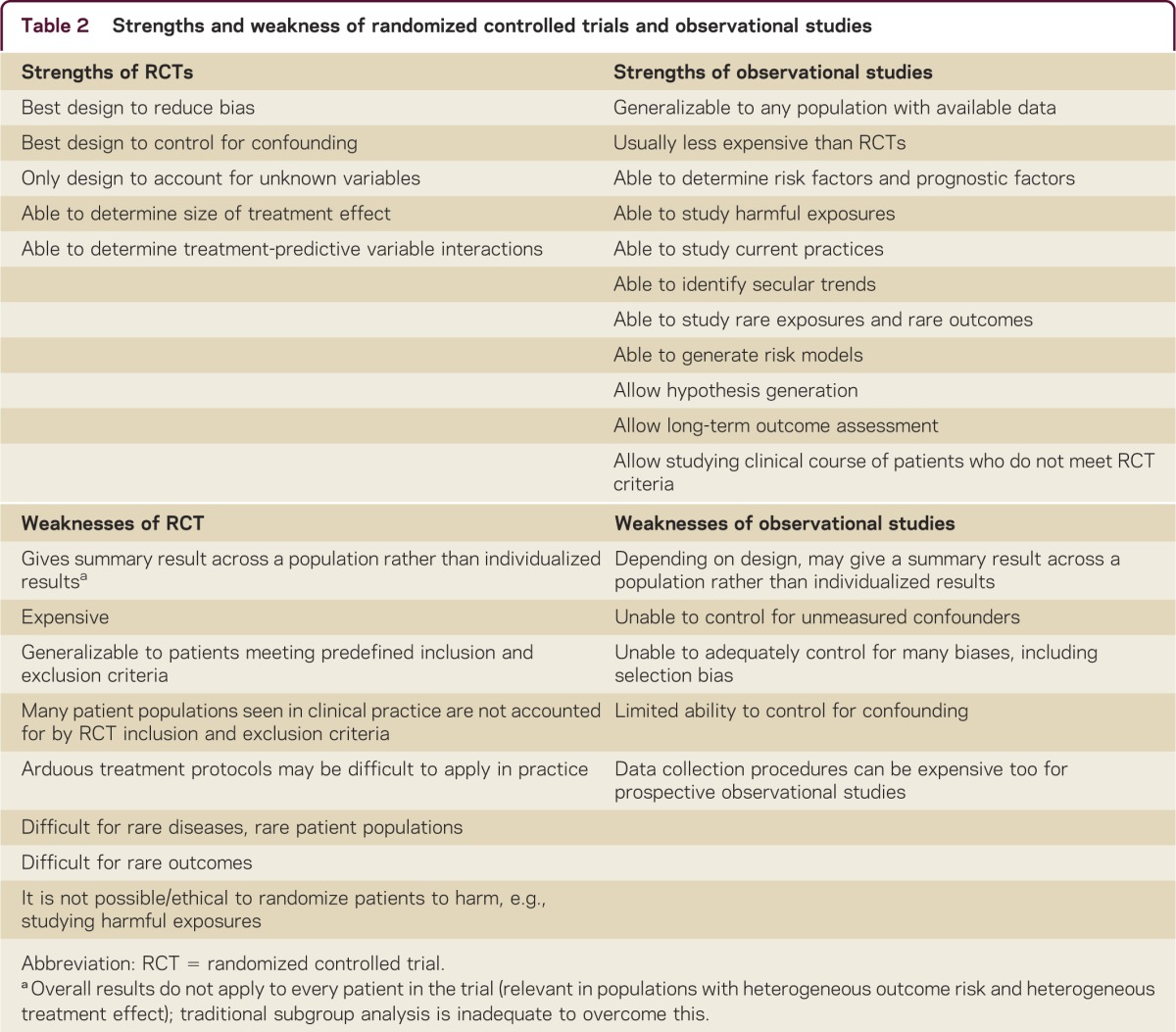

The goal of evidence-based medicine is to put treatment initiatives under scrutiny and to establish a scientific basis for the use of medications and the appropriateness of tests.1 Practicing medicine according to beliefs that are not supported by strong evidence of benefits outweighing risks is viewed as inappropriate and wasteful. Blind RCTs are considered the strongest evidence source for reliable results.1,2 It is universally accepted that such studies provide Class I evidence when designed and conducted appropriately.2 RCTs have the unique ability to adequately control for bias generated by unknown confounders, the placebo effect, co-interventions, and selection bias through use of randomization, placebo, blinding, and allocation concealment. However, RCTs are not without limitations. These include the applicability of RCT results to a broader population of patients and clinical settings and that RCTs give a summary result for the studied population rather than the individual patient (table 2).3 Rare conditions and conditions with multiple contradictory RCT results are additional obstacles. Even methods such as meta-analyses may fail to provide definitive answers. This is particularly true when heterogeneity of patient populations, treatment protocols, and treatment effects reduce the validity of meta-analyses. In addition, comparisons between randomized and nonrandomized studies yield overall good correlation particularly when contemporary rather than historical controls are used, although this finding is inconsistent.4

Table 2 Strengths and weakness of randomized controlled trials and observational studies

Application of RCT and observational studies in a highly heterogeneous disease with variable prognosis

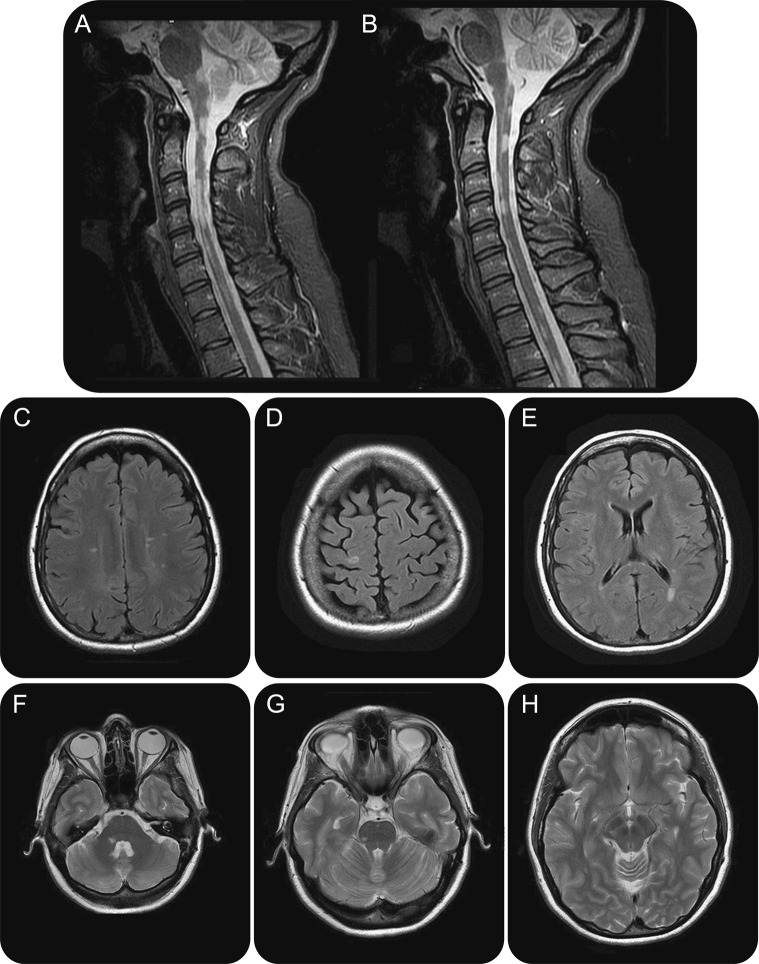

MS manifests with a high degree of heterogeneity. Observational studies have allowed an understanding of this heterogeneity based on clinical features, MRI, and immunology. Clinically, African-American race and frequent relapses are associated with long-term poor prognosis and different treatment responses.5 MRI features such as presence of infratentorial and spinal cord lesions are associated with high risk of disease progression (figure 1).6 Furthermore, MRI enables monitoring responses to treatment and detecting continuous subclinical activity in absence of clinical relapses, before exhaustion of compensatory mechanisms leads to clinical manifestation and irreversible damage.7 Subclinical disease activity is a gradual process that represents a missed opportunity to prevent disability, as immune therapies are less likely to work after extensive damage has occurred (figure 2).8 Understanding and identifying heterogeneity of both prognosis and treatment response can inform RCT design and interpretation. In addition, heterogeneity of prognosis and treatment response are closely linked to the 2 major limitations of clinical trials: generalizability to non-RCT populations and that the results are measured as a summary effect (table 2).

Atypical presentation of multiple sclerosis, illustrative of heterogeneity of disease

Figure 1. Brain MRI of a 39-year-old woman diagnosed at age 25 years, who continued to accumulate motor disability related to spinal cord involvement (A, B) and relative sparing of the brain parenchyma (C–H), despite attempts to treat with interferon, glatiramer, cyclophosphamide, and natalizumab.

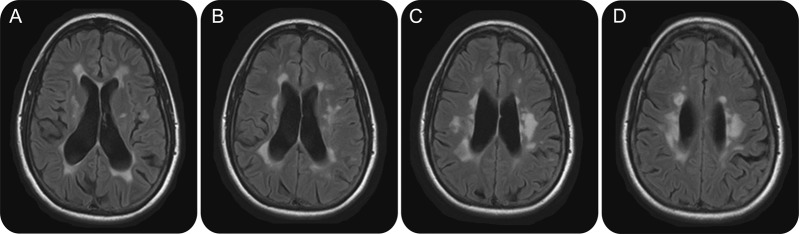

Subclinical disease activity represents a missed opportunity to prevent disability

Figure 2. Brain MRI of a 50-year-old woman with longstanding multiple sclerosis demonstrates confluent white matter signal abnormalities in the periventricular areas accompanied by diffuse parenchymal volume loss (A–D) secondary to advanced bilateral demyelination. In the course of her life, the patient could evoke a limited number of clinical relapses that have almost invariably resolved spontaneously.

For example, recruitment of patients in different stages of their disease may explain why trials of injectable therapies (glatiramer acetate and interferons) that were conducted in the 2000s showed a larger reduction in relapse rate than those conducted in the 1990s.9 The treatment effect measured in RCTs is made of a mixture of outcomes from patients who have a full response combined with outcomes from nonresponders. It has been demonstrated that when the nonresponders are reciprocally switched, an increased treatment effect is obtained.10 In other words, RCTs give results measured as a central tendency. Furthermore, as the risk of the primary outcome is often not normally distributed across patients within an RCT, the summary result may not be what most patients would typically experience, and the few patients at high risk of the primary outcome may drive the measured effect. Of note, traditional subgroup analysis in RCTs is insufficient to overcome this problem, as it is at risk of being underpowered and of generating false-positive results. However, many observational studies are not immune to these limitations when there is heterogeneity of treatment effect (table 1). The lack of demonstrable long-term efficacy of interferon on disability in a recent long-term prospective cohort study can be viewed as due to its indiscriminate use related to inability to select the patients who actually benefit from the therapy.11

Observational studies and advances in understanding disease mechanisms can help overcome the limitations of generalizability and summary effect issues of the RCTs. This can be achieved by conducting separate trials for more selected patient populations to limit heterogeneity, analysis based on previously validated risk profiles, RCTs using sliding dichotomy analysis, or identifying individualized predictors of prognosis and treatment response.12 In this vein, there are encouraging preliminary findings in prediction of individualized treatment responses. A distinct pretreatment immunologic profile, tested by gene expression, has identified individuals who demonstrated breakthrough disease activity while on interferon.13,14

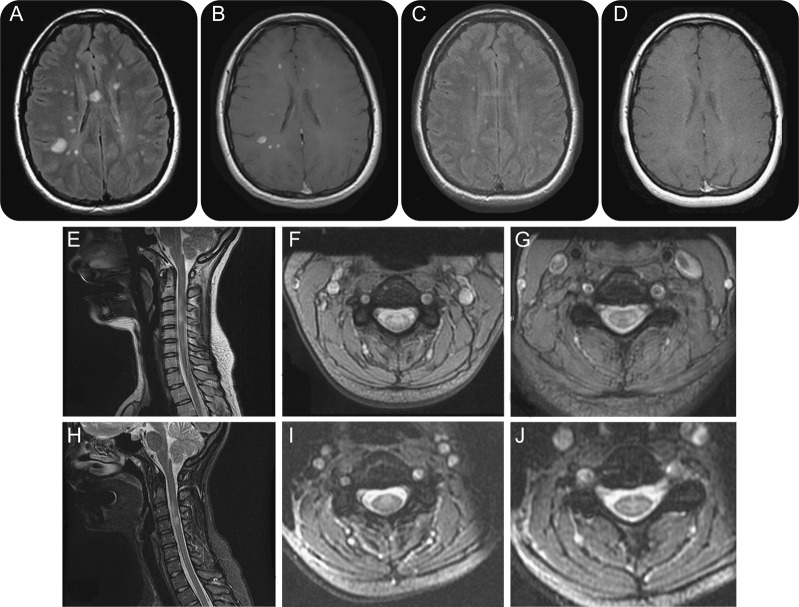

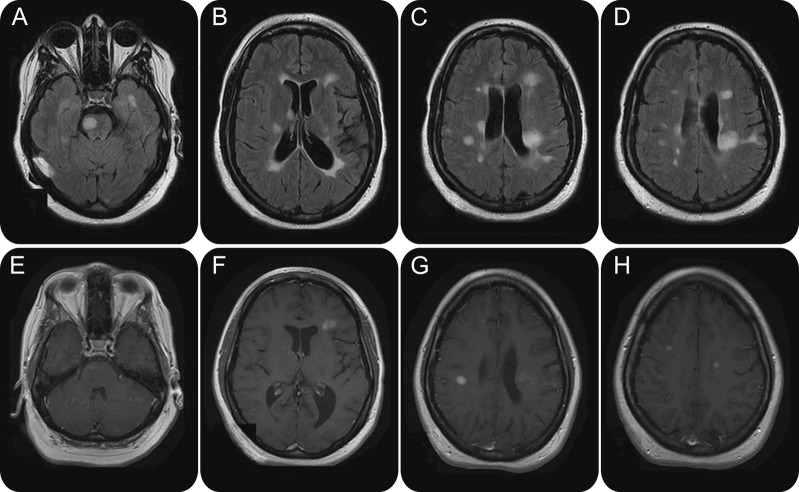

The heterogeneity of clinical presentations, prognosis, and treatment response in patients with MS needs to be taken into account when counseling for prognosis and in decision-making for treatments. Evidence from clinical trials requires interpretation for applicability to individual patients and in the absence of specific parameters predictive of a treatment response, the chances of picking the right medication are improved but not guaranteed by these studies. In the end, what matters to patients is how they do individually, not as a group. Currently, the trial and error approach remains necessary and is often adopted in clinical practice when initiating a therapy for treatment-naive patients, as patients often have different responses to the same initial therapy (figures 3 and 4).

Multiple sclerosis responsive to treatment

Figure 3. Brain MRI of a 23-year-old woman who presented with dizziness and sensory complaints. At the time of symptoms onset, MRI demonstrated multiple areas of signal abnormalities with typical appearance of a demyelinating process. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (A) and postcontrast sequences (B) are shown. Spinal cord involvement was present (E–G). MRI was repeated after 6 months glatiramer acetate therapy. Substantial improvement is noted in the FLAIR sequences (C) and resolution of the postcontrast enhancement (D). Subtle improvements are appreciated at the cervical cord as well (H–J).

Multiple sclerosis nonresponsive to treatment

Figure 4. Brain MRI of a 24-year-old woman treated with glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis since diagnosis 2 years prior, who presented with new-onset right hemiparesis and facial palsy. Multiple areas of demyelination accompanied by volume loss are detected in the fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences (A–D). Several contrast-enhancing lesions are noted in the right brainstem (E), consistent with the new neurologic deficits, as well as bilateral white matter (F–H). Findings are consistent with an aggressive form of a demyelinating disease that failed to respond to the injection therapy.

Observational studies may help when RCTs are impractical

Some patients with MS need to switch treatment because of poor control of their disease and have alternative options available; they are unlikely to agree to being randomly assigned to another treatment. In fact, a randomized study to assess the comparability of natalizumab to glatiramer acetate and interferon β-1a was discontinued in 2011 because of difficulties with enrolling patients.15 With the same purpose of obtaining information on outcomes for patients switching from one therapy to another, a retrospective analysis of patients with MS who had breakthrough disease on injection therapies demonstrated 65%–68% reduction of the relapse rate after switching to a second-line agent.16 Besides overcoming the impracticality of the rigorously designed RCT mentioned above,15 registries allow to study rare situations and outcomes through the collection of data from large numbers of patients. They also reflect real-life experience that is typical of current patient populations and practices.17 As an example, the prevalence of progressive multifocal leukoencephalitis associated with natalizumab as well as descriptions of patient-centered outcomes have been captured through the mandatory database much more accurately than the original RCT.

Caring for patients not represented in RCTs

Several agents are approved based on RCTs for anticoagulation after ischemic stroke due to atrial fibrillation. However, there is no RCT on how and when to start warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban after stroke. The RCTs of oral anticoagulation enrolled patients >2 weeks after stroke onset. Using clinical judgment, it may be argued that for patients with small infarcts without edema, at low risk of hemorrhagic transformation, oral anticoagulation should be started early, whereas for those with large infarcts with edema, initiation of therapy should be postponed to 2 weeks after stroke.18

The collection of data remains essential because there are many variables that could influence outcomes and outside the context of clinical trials, careful observations and annotations of events from clinical practice can generate those data. Indeed, factors related to age, preexisting pathologies, anatomic variants, and comorbidities that could have excluded a patient from participating in a clinical trial (and eliminated the possibility of knowing what would have been the outcome) are realities that challenge physicians.

To care for patients like these who are excluded from trials, we advocate using clinical judgment to balance the limitations of (1) generalizing RCT results from other populations, (2) biases in observational data, and (3) inaccuracies of current understanding of disease and therapies. The experience acquired by practitioners needs to be tested for validity rather than dismissed because never tested in a randomized fashion.

Clinical judgment informing design and interpretation of clinical trials

The treatment of myasthenia gravis is based on a limited number of RCTs; the recommendations derive from expert opinion. The pathophysiologic processes have been fairly well-elucidated and the diagnostic steps are relatively simple. The challenge is in limiting steroid use to reduce their long-term detrimental effects. Recently, a RCT failed to demonstrate superiority of mycophenolate mofetil, a medication that neurologists have prescribed for decades, over prednisone.19 The RCT did not provide undisputed evidence. Concerns are raised on the duration of therapy and regarding the design of the study, where all patients received prednisone and either placebo or added-on mycophenolate. Physicians are allowed the discretion to propose to patients a treatment that by experience or by known mechanisms might work. Steroid-sparing immunotherapy for myasthenia should not be abandoned but rather further pursued and better refined, and more trials are underway. Clinical expertise and judgment are essential to designing and redesigning RCTs and in implementing the evidence generated by them. This is because not all RCTs are well-conducted or well-designed, and generalizability (applicability) is often troublesome. For many years, plasmapheresis and IV immunoglobulins have been used to treat myasthenia and myasthenic crises. The comparable efficacy has only recently been validated in a small RCT.20

RCTs may not lead to one-size-fits-all medicine

As evolution favors diversity, nature does not exist in discrete entities but rather in a continuum of states. Classifying conditions into diagnostic categories is a necessity that creates the problem of artificially forcing phenotypes into classes; subjects within a class may actually be the expression of distinct underlying genotypes with an unlikely chance to respond to the same therapy. The failure of every well-designed RCT to demonstrate efficacy of treatments in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has been viewed as an example of such. The several gene mutations identified in patients with ALS are the clue to understanding that different treatments have to be based on biology rather than embarking in large RCTs designed as one-size-fits-all (Cudgovicz, personal communication, 2013).

Another issue applicable to RCTs is the presence of a treatment-variable interaction where patients with a given characteristic have a larger or smaller treatment effect than the rest of the population. In the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs Stenting Trial of carotid stenting vs endarterectomy for extracranial carotid stenosis, an interaction was found between age and treatment, with equivalence of the 2 therapies for patients aged 70, preferential benefit from stenting at younger age, and preferential benefit from endarterectomy in older patients. This interaction allows clinicians to use the results of a “neutral” noninferiority study to individualize recommendations, particularly at the extremes of patient age, as the treatment effect is amplified at different ages.21

Secondary prevention of stroke is an example of where multiple RCTs in predefined subgroups have allowed us to choose therapies based on patient groups, e.g., small-vessel disease, symptomatic high-grade extracranial atherosclerosis, symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis, and stroke due to atrial fibrillation. While this may not be considered truly decision-making on an individual basis, it is a clear advancement from the one-size-fits-all criticism of RCTs.

Prioritizing data acquisition through RCTs and registries

For several years, stroke trialists have used an ethical hierarchy to make decisions in medical emergencies.22 In this paradigm, patients presenting with acute stroke are first offered standard care that is based on high-quality evidence from completed RCTs. The second step is to offer the patient enrollment in a clinical trial. Third, if no appropriate RCT exists, which is the typical scenario, the patient is offered guideline-based/consensus-based management plans. These patients should ideally be captured in prospective registries. The fourth step, for patients who still pose a clinical question, involves considering empiric therapy based on best judgment and experience of the providers.

This approach allows maximizing enrollment in RCTs, which provide novel therapies based on clinical equipoise in a setting where safety is monitored closely. This is preferred over skipping the RCT step, which shuttles patients away to off-label therapies without appropriate monitoring of patient safety or the opportunity to learn. This combination allows access to the most unbiased evidence from RCTs and the most generalizable evidence from registries.

Other barriers remain to RCT enrollment and in some cases play a more influential role; notably, financial incentives and the belief that a therapy is effective based on previous observational data. This is particularly true for conditions that are perceived to be high-risk with reasonably safe interventions. Stenting with the Wingspan stent for symptomatic high-grade intracranial stenosis is a good example of this. Registry data were more optimistic than the eventual results of the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial, which refuted the benefit of using the Wingspans stent and in fact demonstrated harm.23,24 By controlling reimbursement for intracranial stenting, the Centers for Medicare Services (CMS) played an important role in preventing patients from being shuttled away from enrollment in SAMMPRIS. Had CMS decided to reimburse for intracranial stenting based on registry data, many of these patients would have had stenting to their detriment outside of the SAMMPRIS setting and the scientific community would have remained none the wiser.

DISCUSSION

Customizing therapies to individuals is the key to succeeding with minimal risks of complications, but individualized medicine is hampered by the difficulties in early recognition of (1) subtypes of diseases, (2) subgroups of patients, or (3) treatment-variable interactions. Rather than negating the utility of well-designed and well-conducted observational studies, investments should be made to promote that type of research alongside RCTs. It is a disservice to society to divert patients away from RCTs and a disservice to patients not to inform them of RCTs' existence. Similarly, it is a disservice to disregard the opportunity to conduct observational studies that may address some of the RCTs’ limitations, as they are more generalizable and can help inform risk, prognosis, and in rare instances effectiveness. Improving our understanding of the underlying biology and generating methods to predict individualized outcomes may help address the limitations of RCTs. This can be facilitated by integration of RCTs and observational studies infrastructure and educating health providers on appropriate interpretation of all study designs. For most neurologic conditions, it is not a question of whether to rely on RCTs or observational studies in our efforts to achieve personalized medicine, but rather to use all of our tools appropriately.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

Correspondence to: rbomprez@gmail.com

Funding information and disclosures are provided at the end of the article. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

Footnotes

Correspondence to: rbomprez@gmail.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jane-wit D, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Variation in results from randomized, controlled trials: stochastic or systematic? J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ioannidis JP, Haidich AB, Pappa M. Comparison of evidence of treatment effects in randomized and nonrandomized studies. JAMA. 2001;286:821–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waubant E, Vukusic S, Gignoux L. Clinical characteristics of responders to interferon therapy for relapsing MS. Neurology. 2003;61:184–189. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078888.07196.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gholipour T, Healy B, Baruch NF, Weiner HL, Chitnis T. Demographic and clinical characteristics of malignant multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;76:1996–2001. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e559d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris JO, Frank JA, Patronas N, McFarlin DE, McFarland HF. Serial gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scans in patients with early, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: implications for clinical trials and natural history. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:548–555. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyle PK. Early treatment of multiple sclerosis to prevent neurologic damage. Neurology. 2008;71:S3–S7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31818f3d6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodin DS. Disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: update and clinical implications. Neurology. 2008;71:S8–S13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31818f3d8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle PK. Switching algorithms: from one immunomodulatory agent to another. J Neurol. 2008;255:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-1007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirani A, Zhao Y, Karim ME. Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2012;308:247–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent DM, Hayward RA. Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients: the need for risk stratification. JAMA. 2007;298:1209–1212. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandenbroeck K, Comabella M. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in response to interferon-beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010;30:727–732. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesse D, Krakauer M, Lund H. Breakthrough disease during interferon-[beta] therapy in MS: no signs of impaired biologic response. Neurology. 2010;74:1455–1462. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1a94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biogen Idec. Study Evaluating Rebif, Copaxone, and Tysabri for Active Multiple Sclerosis (SURPASS). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01058005. Accessed November 9, 2012.

- 16.Castillo-Trivino T, Mowry EM, Gajofatto A. Switching multiple sclerosis patients with breakthrough disease to second-line therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurwitz BJ. Analysis of current multiple sclerosis registries. Neurology. 2011;76:S7–S13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820502f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berge E, Abdelnoor M, Nakstad PH, Sandset PM. Low molecular-weight heparin versus aspirin in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: a double-blind randomised study: HAEST Study Group: Heparin in Acute Embolic Stroke Trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanders DB, Hart IK, Mantegazza R. An international, phase III, randomized trial of mycophenolate mofetil in myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2008;71:400–406. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312374.95186.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barth D, Nabavi Nouri M, Ng E, Nwe P, Bril V. Comparison of IVIg and PLEX in patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2011;76:2017–2023. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voeks JH, Howard G, Roubin GS. Age and outcomes after carotid stenting and endarterectomy: the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial. Stroke. 2011;42:3484–3490. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.624155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyden PD, Meyer BC, Hemmen TM, Rapp KS. An ethical hierarchy for decision making during medical emergencies. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:434–440. doi: 10.1002/ana.21997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaidat OO, Klucznik R, Alexander MJ. The NIH registry on use of the Wingspan stent for symptomatic 70-99% intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2008;70:1518–1524. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306308.08229.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]