Abstract

Background

The Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines recommend providing multidisciplinary geriatric assessment in the Emergency Department (ED), but these assessments can be difficult to coordinate and may prolong length of stay. Patients who need longer than a typical ED stay can be placed in an ED Observation Unit (Obs Unit). We investigated the effects of offering multidisciplinary assessments for ED patients in an Obs Unit.

Methods

Evaluation by a geriatric hospital consultation team, physical therapist, case manager, and/or pharmacist was made available to all Obs Unit patients. Use of any or all of these ancillary consult services could be requested by the Obs Unit physician. A retrospective chart review of random older adult Obs Unit patients was done to assess rates of consult use and interventions by these consulting teams. All patients ≥ 65 years old in our IRB approved, monthly Obs Unit quality database from October 2015 through March 2017 were included.

Results

Our quality database included 221 older patients over 18 months. The average age was 73.3 years (range 65–96) and 55.2% were women. The average observation length of stay was 14.7 hours (±6.5 hours). The majority (74.3%) were discharged from the Obs Unit and 72 hour ED recidivism was 3.6%. Overall, at least one of the multidisciplinary consultant services were requested in 40.3% of patients (n=89). Additional interventions or services were recommended in 80.0% of patients evaluated by physical therapy (32 of 40 patients), 100% of those evaluated by a pharmacist (5 of 5 patients), 38% of those evaluated by case management (27 of 71 patients), and 100% of those evaluated by a geriatrician (8 of 8 patients). Only 5.4% (n=12) of patients were placed in observation specifically for multidisciplinary assessment; these patients had an average length of stay of 12.2 hours and an admission rate of 41.7%.

Conclusions

Incorporating elements of multidisciplinary geriatric assessment for older patients is feasible within an observation time frame and resulted in targeted interventions. An Obs Unit is a reasonable setting to offer services in compliance with the Geriatric ED Guidelines.

Keywords: geriatrics, observation unit, physical therapy, length of stay, Geriatric ED Guidelines

1. Introduction

The Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines recommend multidisciplinary geriatric assessment for all at-risk older adults.1 However, coordinating multidisciplinary assessments in the Emergency Department (ED) is challenging. To perform a comprehensive geriatric assessment, a team of physical therapists, pharmacists, case managers, social workers, and geriatricians is needed.2 These consultants are often constrained to business hours and may not be able to integrate into the 24 hour patient flow dynamics of an ED.3,4 Additionally, performing these assessments frequently prolongs the ED length of stay, which is a nationally reported hospital metric. 5 The national average for an ED stay is 2.2 hours but geriatric evaluation increases the average ED length of stay to over 6 hours.6

Like many other EDs, our hospital does not have extra funding for geriatric trained staff to perform geriatric assessments. Additionally, we have a focus on decreasing our patient length of stay in the ED. Our solution to this conundrum was to integrate existing hospital consultants with geriatric training into the ED Observation Unit (Obs Unit). Observation is a status used when further work up or care is needed prior to a safe discharge, but the patient does not meet admission criteria. Older adults are often cared for in Obs Units for chest pain, syncopal episodes, or neurologic events.7–10 Protocols are used to streamline care and focus on the specific acute complaint in the ED. For example, a patient with chest pain and concern for coronary artery disease could be placed on the Chest Pain protocol. The patient would then receive serial cardiac enzyme and EKG testing and an appropriate cardiac stress test. However, these chief complaint-focused protocols may not be appropriate for older adults, who can present atypically or have underlying socioeconomic problems and comorbidities that affect their care. Prior studies have found that over 70% of older patients in ED Obs Units have unmet needs or unrecognized geriatric syndromes.11,12

We convened a Geriatric ED Improvement taskforce consisting of ED nurses, ED physicians and advanced practice providers, geriatricians, case managers, physical therapists, and pharmacists. The hospital’s inpatient geriatric consultation team and physical therapists agreed to prioritize Obs Unit patients with early consultations Mondays through Saturdays. Pharmacists and case managers also committed to expedited assessments in the Obs Unit. Two new Obs Unit protocols, called Frailty and Fragility Fracture, were developed. The Frailty protocol was for any older adult in the ED with a reassuring initial ED work up who did not require inpatient care. If the ED physician had concerns about a possible need for home health services, home safety, or skilled nursing facility placement the patient could be placed in the Obs Unit on the Frailty protocol for further evaluation by physical therapy, geriatrics, and case management. The Fragility Fracture protocol was designed for any adult at risk for fragility fracture by age (women ≥50 years old and men ≥65 years old) or comorbidities, or for any adult with a fracture and concern for how this injury would affect their function at home. The Fragility Fracture protocol orderset suggests consultation by physical therapy, geriatrics, case management, and endocrinology (for osteoporosis treatment recommendations).

The multidisciplinary assessments were not bundled or mandatory, so the ED team could choose to consult one or all of the new multidisciplinary services as needed. Anecdotally we saw that these multidisciplinary consultants were being asked to see older adult patients on other protocols as well, such as chest pain or transient ischemic attack. We wished to understand further how ED physicians were integrating these multidisciplinary assessments into the care of Obs Unit patients. To evaluate the impact of this program, we examined all older adult patients in our quality database since the start of these protocols. Our main outcome was rate of use of the geriatric protocols and the number of multidisciplinary consultations.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

This retrospective chart review study was approved by our institutional review board. An electronic medical record Dashboard query (EPIC R, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, Wisconsin), was used to identify ED patients who had a transfer to observation order placed October 2015 through March 2017. Ten percent of all patient visits to Obs Unit by those 18 years and older were randomly selected for chart review each month. These selected charts were then evaluated for inclusion in the quality database. Exclusion criteria included patients for whom an observation order was placed, but their disposition was changed prior to an observation stay. This was determined by length of stay in observation status < 1 hour, but also by excluding any patient without a note detailing their final disposition from observation status. Only assessments undertaken when the patient was in the Obs Unit were included. Chart abstractors included trained Emergency Medicine residents, faculty, and medical students. They were not blinded to the purpose of the quality database, which was designed to assess rates of use of the Obs Unit in general and rates of protocol and consultant use to determine if certain protocols were performing differently in the quality metrics. These data were used by our ED administrative team to discuss with consultants, assess ordersets and fidelity to protocols, and teach physicians and residents about appropriate patient placement in observation. No power analysis was done as this is a descriptive subgroup analysis of a quality database. A standardized chart abstraction sheet was used. Data were collated using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA).

2.2 Setting

An academic tertiary care referral hospital with an ED volume of 80,000 patient visits per year and a 20 bed Obs Unit within the ED. The unit is a Type 1 complex unit with 37 different protocols, including a “general” protocol for patients that do not fit easily into any defined protocol.13 Only ED physicians can place patients in the unit. The Obs Unit has 24 hour advanced practice provider coverage and dedicated nurses who are cross trained in short stay and ED care. Our Obs Unit cares for 6,400 patient visits per year of whom 19% are ≥65 years old.

2.3 Multidisciplinary assessments

The hospital’s geriatric service consists of a board-certified geriatrician, geriatric fellows, and geriatric nurse practitioner. The geriatric consult team was available Monday through Saturday. Hospital physical therapists performed the physical therapy evaluations Monday through Saturday. Nurse case managers were available initially weekdays only but midway through the study period this extended to daily. Pharmacist medication reviews by ED pharmacists were initiated 6 months into the study period and were available on weekdays only. For the purpose of clarity, we will use the term “consultant” to refer to any one of these teams. There were no specific criteria for consultations; criteria for consultation was left up to the ED physician.

For the purpose of interventions, we developed a data dictionary. Interventions were considered care suggested or done by the consultant that was not a part of the emergency medicine teams’ care plan or in progress already. All interventions were reviewed by 2 reviewers and if there was not agreement as to whether the activity counted as an intervention, a third reviewer was engaged.

2.4 Analysis

Patients were divided into two groups- those who received at least one assessment by a consultant (case management, physical therapy, geriatrics, or pharmacy) and those who received standard care without any additional assessments from the multidisciplinary team. Descriptive statistics including means and proportions were obtained with Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Comparison testing was done with Mann Whitney Wilcoxon Tests (EngineRoom Web Based Data Analysis Software, MoreSteam, Powell OH).

3. Results

3.1 Patient selection

Over the 18 month study period, 10,833 observation orders were placed in the ED for patients of all ages. Ten percent (n=929) of charts were randomly selected each month for review. All patients ≥ 65 years of age were included in this analysis (n=221, 23.9%).

3.2 Patient characteristics

The 221 patients had an average age of 73.3 ±6.8 years and were 55.2% female (Table 1). No patients in this series died or required admission to an intensive care unit. Returns to the ED within 72 hours of discharge occurred in 3.6% of patients. ED recidivism was not associated with multidisciplinary consultant use (p=0.97). The majority of patients were placed in observation for reasons other than frailty, with neurologic and cardiac complaints being most frequent (Table 2). Only 5.4% were on one of the geriatric-specific protocols, Frailty (n=9) or Fragility Fracture (n=3). Admission was avoided for 44% (4 of 9) of the Frailty patients, and only one of these patients returned to the ED within 72 hours. The diagnosis at the return ED visit was acute delirium and pneumonia. This patient had received assessments from pharmacy, case management, and physical therapy but had not been seen by a geriatrician during the initial visit.

Table 1.

Incorporation of multidisciplinary assessments into an ED Obs Unit did not prolong length of stay or affect admission rates.

| All Patients N= 221 |

≥1 consultation N=89 |

No consultations from the multidisciplinary team N=132 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.3 ±6.80 | 74.7 ±7.8 | 72.3 ± 5.89 |

|

| |||

| Female (%) | 55.2% | 57.3% | 53.8% |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity (% Caucasian Non-Hispanic) | 76.9% | 78.3% | 76.2% |

|

| |||

| Most Common Protocols* | TIA-18.1% Chest Pain- 13.1% General- 9.0% Back Pain- 5.4% Cellulitis- 5.4% |

TIA- 19.1% General- 10.1% Frailty – 10.1% Chest pain- 9.0% Back pain- 9.0% |

Chest Pain- 18.2% TIA- 17.4% General- 8.3% Cellulitis- 7.6% COPD- 3.8% |

|

| |||

| Admitted§ | 25.7% | 25.8% | 25.7% |

|

| |||

| Length of stay in Observation (Hours)§ [95% Confidence Interval] | 14.7 (Range 1.1 – 42.7) [13.9–15.6] | 15.3 (Range 1.1 – 35.5) [14.1–16.8] | 14.3 (Range 1.7 – 42.7) [13.2–15.4] |

TIA = transient ischemic attack protocol

Most common protocols do not add up to 100% due to the variety of protocols with small numbers of patients that are not listed.

p value non significant.

Table 2.

Older adults are placed in observation for a variety of evaluations. The two protocols specific for multidisciplinary assessment, Frailty and Fragility Fracture, had reasonable length of stay but higher admission rates.

| Number of patients | Admission Rate* | Length of Stay | Geriatrics | Physical Therapy | Pharmacy | Case Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurologic (TIA, vertigo, headache) | 21.7% (N=48) | 25.0% [14–40%] | 16.5 ±6 | 0% | 27.1% | 0.0% | 20.8% |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiac (chest pain, Hypertensive urgency, CHF, syncope, palpitations) | 22.6% (N=50) | 20.0% [10–34%] | 15.8 ±7 | 2.0% | 4.0% | 2.0% | 18.0% |

|

| |||||||

| Injury (Trauma, head injury, back pain) | 9.5% (N=21) | 23.8% [8–47%] | 12.5 ±6 | 0% | 38.1% | 5% | 47.6% |

|

| |||||||

| Pulmonary (asthma/COPD, pneumonia/influenza) | 4.5% (N=10) | 10.0% [3–45%] | 13.5 ±5 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0.0% |

|

| |||||||

| Renal (renal colic, hematuria, pyelonephritis) | 5.9% (N=13) | 15.4% [2–45%] | 16.0 ±4 | 0% | 7.7% | 7.7% | 61.5% |

|

| |||||||

| Geriatric (frailty, fragility fracture) | 5.4% (N=12) | 41.7% [15–72%] | 12.2 ±5 | 58.3% | 83.3% | 8.30% | 66.7% |

|

| |||||||

| Soft Tissue infections (cellulitis) | 5.4% (N=12) | 33% [10–65%] | 15.0 ±4 | 0% | 0.0% | 0% | 33.3% |

|

| |||||||

| GI (abdominal pain, GI hemorrhage, dehydration) | 9.5% (N=21) | 42.9% [21–66%] | 17.4 ±7 | 0% | 4.8% | 0% | 28.6% |

|

| |||||||

| Others (epistaxis, pharyngitis/dental pain, DVT/PE, back pain, cellulitis, MRI, allergic reaction, and general) | 26.2% (N=34) | 29.3% [13–44%] | 14.0 ±5 | 0% | 8.8% | 0% | 29.4% |

|

| |||||||

| Total: | 221 | 25.8% [20–32%] | 14.7 ±6 | 3.6% | 17.6% | 3.2% | 30.3% |

Admission rate lists mean and 95% confidence interval in brackets.

3.3 Multidisciplinary assessments

Eighty-nine patients (40.3%) were assessed by at least one of the multidisciplinary consultants. There was no significant difference between those who received consultation and those who did not in regards to admission rate (25.8% vs 25.7%, p=0.89) or length of stay in observation (15.3 assessed vs 14.3, p=0.17). Fourteen percent (n=31) received multiple consultations. Multiple consultations did not correlate with differences in admission rate (30.0% vs 23.0%, p=0.32) or length of stay (16.6 vs 14.7, p=0.14) as compared to those who were evaluated by only one consultant.

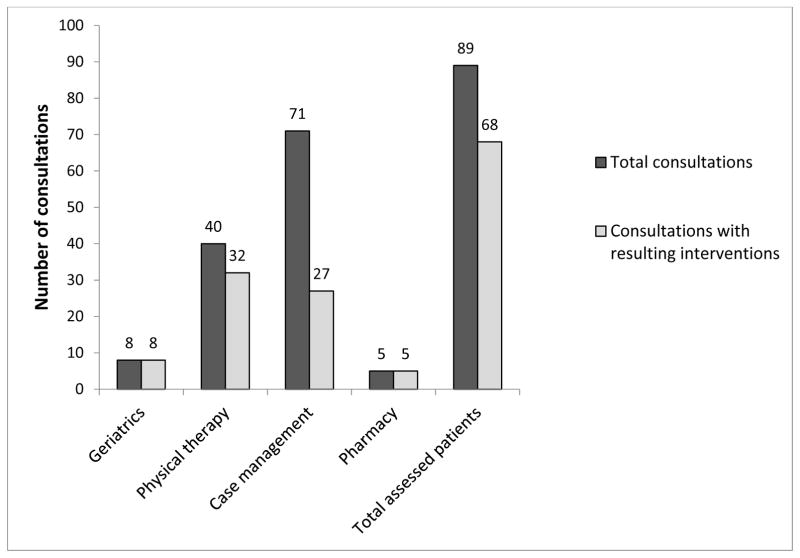

The multidisciplinary consultants were used at a similar rate to other services in the Obs Unit. Twenty one percent of Obs patients (n=46) were evaluated by a neurologist, 11.3% (n=25) by a cardiologist, and 10.8% (n=24) by a surgical service (general surgery, orthopedic surgery, or neurosurgery). In comparison, 30.3% (n=67) received evaluations by case management, 17.6% (n=39) by physical therapy, 3.6% (n=8) by geriatrics, and 2.3% (n=5) by a pharmacist (Figure 1). Multidisciplinary consultations resulted in interventions in 76.4% of patients (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Evaluations by physical therapists, case management, pharmacists, and geriatricians result in identification of issues and further recommended interventions in the majority of cases. Because some patients received assessments from multiple consultants, the total column is not a summation of the prior four columns.

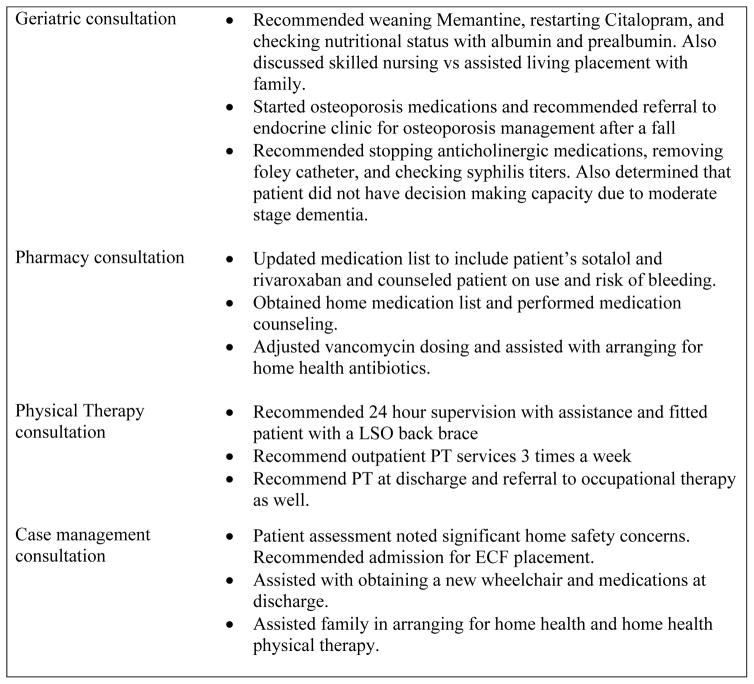

Figure 2.

A sampling of interventions recommended by the multidisciplinary geriatric assessment consultants for different observation unit patients demonstrates the breadth of scope brought by involving consultants from different disciplines.

Patients who presented on weekdays with potential for all multidisciplinary assessments were evaluated. Of those 163 patients, 44.8% received at least one consultation, as compared to 31.0% of weekend patients (p=0.07). Five percent of weekday observation patients (n=8) received geriatric consultations.

4. Discussion

This descriptive study of a random sample of older adults in an ED Obs Unit demonstrates a new method of complying with the Geriatric ED guidelines that does not rely upon lengthy ED stays or geriatric personnel in the ED. Assessments were accomplished within 24 hours of the ED stay and did not prolong length of stay compared to the cohort who did not receive evaluation, or compared to national rates in the United States (22.3 hours).13,14 This pilot study demonstrates that multidisciplinary geriatric assessments can be performed in an ED setting without significantly impacting quality metrics such as length of stay and admission rate.

The overall rate of use of the geriatric protocols, Frailty and Fragility Fracture, was lower than expected, as 94.6% of patients were in observation for other medical reasons. However, the patients in the Obs Unit on other protocols still benefited from the elements of multidisciplinary assessment, with case management and physical therapy evaluation being the most common resources accessed. It is interesting that these teams were consulted as frequently as the cardiologists or neurologists. This is consistent with other studies finding high rates of need when physical therapy and case management services are offered within Obs Units.15–17 Finally, incorporation of multidisciplinary assessment into the Obs Unit demonstrated usefulness, with 76.4% of patients receiving new interventions.

An Obs Unit can be a way to comply with Geriatric ED Guidelines on multidisciplinary assessments for at-risk older adults. The Frailty and Fragility Fracture protocols did not significantly increase length of stay in the Obs Unit, but they may have a higher admission rate than other protocols. From reviewing the admitted patients, this admission rate may be reduced by improved patient selection. Any patient that is non ambulatory prior to Obs placement is unlikely to be able to ambulate safely for discharge home after 24 hours of care. Similarly, an acutely delirious patient would likely be better served in inpatient care, as the one patient who returned within 72 hours was delirious. We would recommend the addition of gait testing and delirium screening to these protocols to assist with patient selection. Additionally, the pharmacy services could likely be better utilized if criteria for pharmacist consultation was implemented.

Our next step is to integrate further suggested care from the Geriatric ED Guidelines, such as standardized assessments for geriatric syndromes. Validated assessment tools have been shown to find higher numbers of unmet needs in geriatric patients.6,12,18 Our rate of 40% deemed in need of assessment is likely missing patients who may have benefitted from multidisciplinary assessments. This suggests that ED provider gestalt alone may be insufficient to recognize older adult needs and referral for comprehensive geriatric assessments.

Illustrating this point, it is unclear why the geriatricians were involved so rarely. This could be due to the sampling process. It is also possible that ED providers did not understand the expertise or services that geriatricians can provide, or it may signify a lack of familiarity with the new consulting service. Further investigation into the low rates of use of this service is needed.

5. Limitations

Conclusions from these data are limited by the small sample size and heterogeneity of the patients and retrospective data collection. We cannot infer as to why some patients received evaluations and others did not. Not all elements of the Geriatric ED Guideline care were implemented or assessed. Full guideline implementation may have different results. Additionally, our patient population was not very racially or ethnically diverse, and unmet needs could be greater in other populations.

6. Conclusions

Multidisciplinary geriatric assessments can be done within an Obs Unit. Assessments of by physical therapy, pharmacy, case management, and geriatrics resulted in high rates of new interventions for older adult patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

LTS, AJV, and LN report no conflicts of interest. TRG reports grant money from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Women’s Health Initiative, grant HHSN-2682016000-02C. JMC reports grant money from the National Institute on Aging, grant R01AG050801.

Glossary

- ED

Emergency Department

- Obs unit

Emergency Department Observation unit

Footnotes

Presentations: This paper has been presented to the IAGG World Congress of Gerontology and Geriatrics (San Francisco, California, July 2017) as part of the symposium “The Critical Role of U.S. Emergency Departments in the Care of Vulnerable Older Adults.”

References

- 1.Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal Older Adult Emergency Care: Introducing Multidisciplinary Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines From the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(7):806–809. doi: 10.1111/acem.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O’Neill D, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d6553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuen TM, Lee LL, Or IL, et al. Geriatric consultation service in emergency department: how does it work? Emerg Med J. 2013;30(3):180–185. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold S, Bergman H. A geriatric consultation team in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(6):764–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CMS and the Office fo the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC); US Department of Health and Human Services. Median Time from ED Arrival to ED Departure for Discharged ED Patients. 2017 https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/measures/cms032v4.

- 6.Aldeen AZ, Courtney DM, Lindquist LA, Dresden SM, Gravenor SJ. Geriatric emergency department innovations: preliminary data for the geriatric nurse liaison model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1781–1785. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caterino JM, Hoover EM, Moseley MG. Effect of advanced age and vital signs on admission from an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen TE, Fuller M, Hartsell S, Hamilton D, Bledsoe J. Prospective evaluation of outcomes among geriatric chest pain patients in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moseley MG, Hawley MP, Caterino JM. Emergency department observation units and the older patient. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):71–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross MA, Compton S, Richardson D, Jones R, Nittis T, Wilson A. The use and effectiveness of an emergency department observation unit for elderly patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(5):668–677. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zdradzinski MJ, Phelan MP, Mace SE. Impact of Frailty and Sociodemographic Factors on Hospital Admission From an Emergency Department Observation Unit. Am J Med Qual. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1062860616644779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foo CL, Siu VW, Tan TL, Ding YY, Seow E. Geriatric assessment and intervention in an emergency department observation unit reduced re-attendance and hospitalisation rates. Australas J Ageing. 2012;31(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross MA, Hockenberry JM, Mutter R, Barrett M, Wheatley M, Pitts SR. Protocol-driven emergency department observation units offer savings, shorter stays, and reduced admissions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(12):2149–2156. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiler JL, Ross MA, Ginde AA. National study of emergency department observation services. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(9):959–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plummer L, Sridhar S, Beninato M, Parlman K. Physical therapist practice in the emergency department observation unit: descriptive study. Phys Ther. 2015;95(2):249–256. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton C, Ronda L, Hwang U, et al. The Evolving Role of Geriatric Emergency Department Social Work in the Era of Health Care Reform. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54(9):849–868. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1087447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wrenn K, Rice N. Social-work services in an emergency department: an integral part of the health care safety net. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(3):247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1994.tb02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosted E, Wagner L, Hendriksen C, Poulsen I. Geriatric nursing assessment and intervention in an emergency department: a pilot study. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]